The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

“In the Park”: Lewis Miller’s Chronicle of American Landscape at Mid-Century

with Emily Pugh, Jessica Ruse, and Courtney Tompkins

II. Lewis Miller, “Guide to Central Park”: A fully annotated, digital facsimile

III. Lewis Miller’s View of American Landscape (Therese O’Malley)

[IV. A Pilgrim in the Park: Sacred Space in Lewis Miller’s “Guide to Central Park” (Kathryn R. Barush)]

IV. A Pilgrim in the Park: Sacred Space in Lewis Miller’s “Guide to Central Park”

Kathryn R. Barush

Lewis Miller (1796 – 1882) was an itinerant artist and carpenter by trade who chronicled, through text and image, “A picture of what [he could] See” from around 1812 until his death. He traveled through America and Europe, “chiefly on foot,” as his biographer Henry Fisher described in an 1885 obituary, and often appears in his own drawings as a gentleman with staff and hat, sometimes walking and sometimes sitting with pencil and sketchbook as he recorded the world around him.[1] His “Guide to Central Park,” created at mid-century, is one example from reams of material that he left for others as, “a mine of thought of inestimable value to everyone” and “a pictureque [sic] looking-glass for the mind.”[2] This essay seeks to interpret Miller’s work as a lived pilgrimage. The artist annotated his album as would a pilgrim “guide” as he drew the scenes around him, perhaps with the intent that others would “walk” his path, in reality or in their imagination. Miller mined religious and sentimental texts for the many quotations accompanying his detailed watercolor drawings, which function as meditations or prayers, often inscribing a secular or natural site with a sacred significance. As Therese O'Malley has shown in her essay, “Lewis Miller’s View of American Landscape” in this issue of Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, Miller created his album partially in situ and partially at home while imaginatively making use of contemporaneous guidebooks, photographs, and images from periodicals to compile his album.[3] With its collection of quoted texts and images, Miller’s “Guide” has a second function as a mnemonic device that Miller could peruse to remember, to meditate upon, and to relive his journey.

From the newly erected iron bridges to the fountains believed in the nineteenth century to contain water with salutary properties for both physical health and spiritual wellbeing, Miller paused with pencil and prayer from pilgrimage station to station to record his own experience. Distinctions between understandings of pilgrimage as motif, metaphor, artistic process, and actual journey have been co-mingled throughout history, resulting in the creation of images that were at once narratives, memorials, and stimuli for contemplative journeys from pictorial space to imagination. Miller’s “guide” certainly does all of this: he pictures himself and others walking and sketching en plein air; he overlays the pictures of sites with religious or sentimental texts (often dealing with themes of mortality), and he encourages the viewer to participate in his journey.

I. Lewis Miller as a Pilgrim-Painter

Miller described his own creative process of drawing and recording as “picturing off” which links the idea of drawing—or “picturing”—to travel, as in “setting off on a journey.” As a German-American Lutheran, raised in the state of Pennsylvania (known for being founded on principles of religious tolerance), Miller’s views of the cultural landscape, including natural and man-made features as well as people, were instilled with a religiously ecumenical and strong moral bent. The notion of pilgrimage underpins many of his extant works. Like most Protestants of his time, Miller would have been aware of the idea of Catholic foot pilgrimages to Rome, Jerusalem, and Canterbury which became, along with bodily relics, a major target of the Protestant Reformation, condemned and discouraged by Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Menno Simons.[4] Martin Luther emphasized that true pilgrimage was a journey of the human soul, toward salvation found through God’s grace.[5] Miller’s journeys, however, were not strictly metaphorical; he was a walker who physically traversed the world, pausing and ruminating at earthly sites, hence combining the Protestant notion of the pilgrimage of life and the Abrahamic practice of site-specific pilgrimages. As an artist, Miller’s process of walking and drawing had an aesthetic as well as spiritual purpose, and the two cannot be separated: his aesthetic vision was seen through the context of the beauty of the world and his own Christian faith. As Victor and Edith Turner have shown, when pilgrimage is not “religiously sanctioned, counseled, or encouraged,” the human need for travel to a place “intimately associated with the deepest, most cherished, axiomatic values of the traveler” will result in the compulsion to seek and find alternate sites to visit, such as gravesites or public parks, whose cultural landscapes recall those of consecrated holy destinations.[6] While Miller did not travel to Jerusalem or Compostela, he did inscribe the ostensibly secular sites of Central Park, and the American landscape in general, with a deeply religious significance.

Pilgrimage can be mediated either through an actual voyage to a holy destination or by a substitute, such as walking the Stations of the Cross or vicariously partaking in a historical pilgrimage through the process of reading, viewing, or—in Miller’s case—drawing the sites he visited in the form of a “Guide.” In the Old Testament, Abraham leaves his home as a “pilgrim and stranger” to seek the land God has promised to reveal (Gen. 12:1–9), and in the New Testament the metaphor of the soul’s journey through the hostile wilderness of the world and toward Christ appears in, for example, John 14:6 and Mark 8:34. In the Middle Ages, literal journeys were themselves understood as metaphorical in the sense that they were microcosmic, geographic versions of the universal pilgrimage of the soul.[7] From a broader perspective of pilgrimages and world religions, past and present, Jas Elsner and Simon Coleman have discussed not only the metaphorical resonances of geographical pilgrimages but also the function of objects and texts as memorials for the pilgrim and as a link to the sacred goal for those who would undertake a future journey.[8]

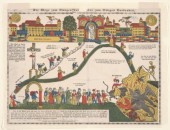

That Miller had knowledge of the meaning of religious pilgrimage is attested to by an undated watercolor in the collection of the York County Heritage Trust, York, Pennsylvania (fig. 1), which is a direct visual quotation from the frontispiece of Zwey bücher von der Zufriedenheit nach den gründen der Vernunft und des Glaubens (Two Books of Contentment after the Establishment of Reason and Faith; Johann Adolf Hofmann, 1748; fig. 2). “Der Wandersmann,” the German word for pilgrim or wanderer, is written at the top of the watercolor, under which a woman in classicizing drapery treads on a serpent. She holds in one hand a book with only the word “gratia” visible on the page, and in the other a mirror on which is inscribed “nature.” For the pilgrim navigating the earthly realm, nature and landscape is seen as a mirror of what is to come; the liminal space where God is revealed “through a glass darkly” (1 Cor. 13:12). To her left is a pastoral and bucolic scene of shepherds and shepherdesses resting and piping under a monumental tree. To her right a pilgrim strides forward. A field stretches behind the woman, lined with trees in front of which deer run and frolic. In addition to the text and iconography borrowed from Hoffmann’s book, Miller quoted passages from William Cowper (1731–1800) (“the path of sorrow and that path alone, leads to the land where sorrows are unknown”) and a poem by Caroline Gilman (1794–1888) (“he seeks the moaning forest trees, he flies! he lists, the wanderer”). Hoffmann’s text, which Miller provides in German, elucidates the lofty purpose of the traveler’s journey, which is no easy sojourn: “The pilgrim pulls his fine coat close, and hastens under the storm of life toward the dwelling place of peace.”[9] The figure of the pilgrim with his coat, staff, and hat negotiating the treacherous territory between this world and the next has been an important emblem in German visual culture from the Middle Ages to Miller’s own time. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), for example, portrayed the mystic theologian Jean Charlier de Gerson in the guise of a pilgrim in a well-known woodcut (fig. 3), and German Romantic poet and critic Ludwig Tieck (1773–1853), used pilgrimage metaphors to propel the narrative in The Wanderings of Franz Sternbald (1798). Goethe, in his Italian Journey, commented on the timeless, dignified dress and attitude of nineteenth-century German pilgrims.[10] Pennsylvania German printed devotional material such as books and broadsides featured the treacherous path the pilgrim must follow to the New Jerusalem—or, alternatively, eternal damnation (fig. 4).

For Miller as a pilgrim-painter, landscapes and nature consistently functioned as temporal reminders of a promised land to come and were mediated through the practices of walking, writing, and drawing. His engagement with what C. Wood has called a “medial shift”[11] from place to page is exemplified in the following passage inscribed on a picture detailing his 1853 trip to the Salt Pond Mountain in Virginia (fig. 5). As is his usual habit, Miller finds an extant text with which to articulate his thoughts, this time taken from the section on the Convent of Saint Anthony on Mount Lebanon, in Our Globe: A Universal Picturesque Album (1868):[12]

Our thoughts assume a more Serious tone, and are apt to elevate themselves in a measure not disproportioned to the great objects which the eye then presents to our Contemplation, filling us with a nameless Silent Satisfaction free from all alloy of Sensual feeling. Common and Earthly Sentiments are left with the world below when man Ascends above the ordinary places, a refuge of men Seeking - in retirement from the world, to forget all earthly Cares, and to devote themselves to Contemplation and Self-Examination to Study free from the interruptions and not Exposed, the peacefulness of _ [sic]abode wrought imperceptibly upon their Souls, and they found among the rocks a heaven of the mind, from which they looked back, only with aversion or pity, on the Scene of turmoil which they had left.[13]

The passage appears alongside drawings of the Salt Pond. One of the views depicts Miller (with his signature hat and staff, reminiscent of a German medieval pilgrim) and his travelling companion, Charles Edie, on their way up the mountain.[14] As in seventeenth-century Dutch landscape paintings that map topographical pilgrimages, the road winds “two-miles from [the] old mill” and up through cultivated land and forest to the summit of the mountain. Both text and image underscore Miller’s convictions about the efficacy of images as a means toward spiritual ascent. The reader, who was not with Miller and Edie that July, could experience it through the “looking glass” of what the artist considered a faithful record.

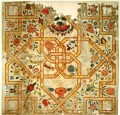

II. Painting as Pilgrimage: Fraktur and German Folk Art

The traditional Pennsylvania German folk art called fraktur that Miller would have grown up with uses, in its more religious manifestations, temporal visual imagery in the form of illuminated pages in order to, as Michael S. Bird has shown, intimate the divine.[15]Fraktur paintings, with their vines and birds intertwined among textual prayers, figures in full-profile, and vicarious pilgrimage labyrinths that the eye can traverse, recall European medieval illuminated manuscripts (fig. 6). Although Miller’s Central Park book also stylistically recalls secular forms of American nineteenth-century art, the spiritual sensibilities achieved through his textual interludes run parallel to the meditative function of fraktur; in particular, his attention to paths, walking, the journey of the pilgrim on earth, and the greater journey of the soul toward heaven. Bird has argued that the art of fraktur “possesses religious significance as an indirect manifestation of spiritual sensibilities rooted in longstanding Christian understandings of mortality and hereafter, sin and redemption, abiding eternal values, and reflections upon earthly life as a spiritual journey.”[16] The traditional art of Pennsylvania was important to Miller, and other works in his extensive oeuvre contain prayers, for family and friends, illuminated with gold-leaf and fraktur memento mori (fig. 7).

Some of the more atypical designs from the Protestant fraktur tradition include frontal portraits of saints with attributes such as books and keys, probably borrowed from the engraved prayer cards common among members of the Catholic community (fig. 8). Miller was unquestionably aware of such objects; he copied Catholic prayer cards and images of the Virgin Mary (fig. 9). One such card depicts a praying and barefoot nun wearing a wimple and veil, her head surrounded by a halo, having a vision of Christ who is flanked by the seven gifts (septum dona) of the holy spirit (fig. 10). The nun’s bare feet (a convention of the discalced Carmelites), white mantle, open book, and vision of Jesus are attributes that indicate that Miller may have been thinking of the mystic and reformer St. Teresa of Avila.[17] Miller may easily have seen pictures of the saint, including prayer cards and printed reproductions of paintings, either in the United States or on his European travels (figs. 11, 12). The picture is fully colored in gray wash with yellow and white highlights and a bright-red sacred heart. The nun/St. Teresa has a book opened in front of her with only the word “Lord” discernible. On the left side of the picture, Miller faithfully copied out the pater noster in Latin (a typical theme in fraktur design) and wrote along the right margin, parallel to the image, a prayer beginning with “Lord” and probably relating to the nun’s book and reflections:

Lead us Safely through this vain and Sinful World, in which we are pilgrims and Strangers, and at length bring us to Everlasting rest through Jesus Christ. Amen.

The decidedly Catholic iconography is hence paired with prayers appropriate for many Christian denominations, with a focus on spiritual ascent (the goal of the pilgrimage) through prayer. Miller’s drawings in the collection at the York Historical Society include portraits of theologians as diverse as Francis Xavier, Emmanuel Swedenborg, and Huldrych Zwingli, attesting to his broad interest in Christian theology across denominations (figs. 13–15). In another album, Miller describes the history and use of the rosary (fig. 16), and elsewhere sketched a Catholic procession (fig. 17). Given his interest in the culture of neighboring religious communities and the function of ritual objects like rosaries, he may well have been aware of the efficacy of the prayer cards he copied and the importance of belief in the idea of the transfer from holy person to object. Whether or not this was an ontological link that he embraced, the Central Park album demonstrates an interest in transferring the salutary benefits of sacred spaces to paper for posterity and prayer.

III. Lewis Miller’s “Guide to Central Park”

Based on the evidence contained in Miller’s sketchbooks and albums, historians have suggested that Miller made several trips to New York City before creating his “Guideto Central Park” around 1867. The trips included departing for Europe in 1840, sailing up the Hudson River and exploring Manhattan, Brooklyn, Long Island, and New Jersey in 1842, and a return trip in the winter of 1859 when he first visited Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s newly unveiled Greensward Plan—Central Park.[18] Olmsted had described the process of designing the park as one which,

necessarily supposes a gallery of mental pictures, and in all parts of the park I constantly have before me a picture, which as Superintendent I am constantly laboring to realize. . . . Consequently except under my guidance these pictures can never be perfectly realized…my picture is all alive – its very essence is life, human and vegetable.[19]

Vaux and Olmsted envisaged their park as a living landscape painting, which meant that Miller’s visual chronicle would be inherently picturesque, with the artist capturing in frames the sites that he found most stimulating to the imagination.[20] Miller’s bright watercolors show walks under the stone and iron bridges, along the banks of the ponds, and by the rustic summerhouses and benches, usually populated with visitors enjoying leisure time. Miller’s continuous religious, didactic, or elegiac text and occasional self-portrait with paper and pen remind the reader/viewer of the unflagging presence of their pilgrim guide.

Miller’s album is a compelling record of one self-proclaimed eyewitness’s religious experience of Central Park. In The Visual Culture of American Religions, Sally Promey and David Morgan have signaled the important role of religion in the “social construction of [American] reality which consists of meaning-making that believers undertake in the visual practices of daily life,” a construct to which Miller’s project of proselytizing, drawing, meditating, and observing neatly corresponds.[21] He underscores his role as guide and witness with self-portraits and first-person narratives, as in the declarative announcement on page 40: “I was in the park.” Miller was not only there (“upon the places and Spot”),[22] but imbued the sites with a personal spiritual significance intended to have a beneficial effect for the reader/viewer. In this sense, his project is consistent with the notion that sacred places are often ordinary and everyday, “ritually set apart to become extraordinary.”[23] Within Central Park, his gaze focuses on small things made holy. In the meadow, the caretaker of the sheep with his rake becomes George Herbert’s spiritual shepherd when Miller emblazons the page with a quote from A Priest to the Temple, or, The Country Parson His Character and Rule of Holy Life (1652): “Now if a shepherd know not which grass will bane, or which not, how is he fit to be a Shepherd” (fig. 18).[24] For Miller, this everyday scene became an opportunity to experience the sacred and to find grace.

Central Park was predicated and built upon Ruskinian principles during a time of medieval revivalism, and Miller was certainly not the only visitor to find parallels between traditional religious structures and experiences and Olmsted and Vaux’s designed environment. Paula Mohr has recently discussed the religious and medieval references throughout the park, arguing that the mid-nineteenth-century Americans experienced a sacred space that was “spatially, temporally, and spiritually distinct from the commercial and industrial city growing up around it.”[25] This removal from the quotidian realm is an important aspect of pilgrimage that allows for spontaneous encounters with others and opens the possibility of renewal and personal, spiritual transformation.[26] Olmsted himself called the park’s structures “as faithful as the most religious of the Middle Ages” and the Sabbath Committee worried that Sunday strolls in the park were replacing traditional church worship (fig. 19).[27] One Sunday in 1860 the New York Herald reported the easing-up of the Sabbatarians in an article entitled “How New York Breathes on Sunday”:

No attempt was made during the day – as announced sometime since – to have tent preaching near the Park upon the immorality of Sunday amusement. The great number of visitors to the Park every Sunday would seem to have disheartened the Sabbatarian fanatics.[28]

Miller was not replacing church with leisure, but rather finding the promise of salvation through the beauty of the landscape. A generation before, poets like Coleridge and Wordsworth had sublimated the landscape through an Augustinian Neoplatonism, where the logos was made visible and could create a liminal point of contact between the earthly, visible world of forms and that of the unseen. In the new age of Transcendentalism, it is not surprising that a Romantic-landscape-painting-cum-park would inspire a comingling of religion and nature.

Visitors in motion populate Miller’s album; walkers are everywhere. Some walk, like the Parisian flâneur, in a leisurely manner without much purpose, by the lakes and water, carrying delicate parasols or swinging canes; others stride ahead with great determination. On page 20, three gentlemen consult a map under the bridge by the old Arsenal, planning the rest of their journey (fig. 20). Some of the figures pause in rest and meditation, allowing their minds to wander and becoming Central Park pilgrims of the more contemplative sort. This turning away from the world and turning in to the spiritual path within are illustrated in fraktur with the visual metaphors of a “narrow path and a strait gate” (as in Matt. 7:13–14), both features of Central Park, which Miller has incorporated into his “Guide.”[29] On page 33, for example, a road winds under the bridge near the Fifty-Ninth Street and Seventh Avenue gate (fig. 21). One walker strides confidently toward the path, which several others have already begun to follow—it winds under the gate and beyond. Another single figure turns from the path and toward the viewer, as if she is imploring the viewer to walk the path as well. Miller, our guide, sits on a rock observing the scene with pencil poised, looking through the gate and at the winding road. Miller is most explicit, however, in the text above his picture, about the intended secondary meaning of this everyday scene. His lines, taken from a Protestant church hymn, are:

How Shall we our course pursue, through life’s uncertain road! what friendly hand will point our view to duty and to God? in lords own words the way is Sure, and plain to every eye; it leads us in a path Secure, to brighter worlds on high.[30]

Miller, with his text and illustration, has shifted a scene of leisure to a spiritual allegory, while retaining all the charm of a picture of an afternoon in the park. With the inclusion of the hymn, the confidently striding gentleman in the foreground with his finger extended becomes the “friendly hand” which will “point our view . . . to God,” and the ascending path under the bridge leads not only into the spiritualized nature of the park, but to “brighter worlds on high.”

On page 52, Miller’s drawing includes four walkers on a path and one figure in a top-hat resting in a summer house at the east end of the Lake (fig. 22). The strolling couples juxtaposed here with the figure resting and looking out over nature again seems to emphasize the active and contemplative aspects of pilgrimage. The long quotation on this page comes from Luther, Psalm CXXVIII, “The Happy Man” in Hymns of the Reformation, which contends with lofty themes of pilgrimage, God-in-nature, and even the Lutheran doctrine of real presence in the Eucharist:

Tell me, wouldst thou wish to go in a path where blessings flow. . . . Clustering vine and olive green, All within thy borders Seen. thus how freely from on high choicest blessings of the Sky on that faithful servant fall, who can trust his God in all. Rich in grace, the holy word fraught with goodness from the lord, Blest and blessing makes him go on his pilgrimage below, And prepares, with Sacred leaven, for the hallowed courts of heaven.[31]

The rustic structure under which Miller’s contemplative figure sits may have recalled, for the artist as it did for other visitors, the link between ecclesiastic architecture and God’s hand in nature— “all within thy borders seen”—as the pilgrim prepares to follow the righteous path “where blessings flow.”[32]

In addition to the overtly religious poems and hymns which emphasized the relationship between the natural world and the heavenly city, Miller also mined popular poetry. On page 31, the quotation is borrowed from canto 3 of Lord Byron’s narrative poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: A Romaunt. Like Miller’s portraits, the poem is self-reflexive: Percy Bysshe Shelley actually referred to Byron as “The Pilgrim of Eternity, whose fame / Over his living head like Heaven is bent,” finding solace in his and Byron’s mutual journeys through the desert and solitude. Like Miller, Byron was not merely adopting a trope, but rather had carefully considered the implication of actual medieval pilgrimage; a notion reinforced by his attention to sacred sites.[33] Miller must have been able to relate to aspects of Childe Harold’s grand tour and the moments of personal transformation that occur through the travelogue. Miller himself went on a very personal pilgrimage to his ancestral home around 1840, and tellingly it is one of Byron’s stanzas about Germany (and his beloved Rhine) that he manipulates and overlays on the scenery of Central Park. Byron wrote:

The castled crag of Drachenfels

Frowns o'er the wide and winding Rhine,

Whose breast of waters broadly swells

Between the banks which bear the vine[.] [34]

In Miller’s drawing, trees grow atop a large bit of stone, from which a small waterfall gushes in dotted lines, indicating movement. There are no walkers in this picture; just a lone figure on a bench, contemplating this living painting as Olmsted intended. Miller’s altered version of Byron’s Spenserian stanza reads:

The Cataract, a Small water fall in a neck of the

Lake, its breast of waters broadly Swells,

Between the banks that bear the Vine.[35]

By quoting Byron’s well-known poem, Miller implicitly signals the pilgrim-knight’s travelogue. The content of the poem and drawing reinforce Olmsted’s vision of the park as a sacred space; for him, the proliferation of nature over the man-made suggested a spiritual truth.[36] Miller, as one visitor and witness, located this truth in the “banks that bear the Vine.”

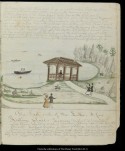

Like many visitors to Central Park, Miller was intrigued by the quality and quantity of public drinking fountains in the park: on page 51, under a drawing of a man pausing at a pump (again, significantly pausing along a walking-path), Miller notes, “The Hydrant water pluck. Pump and pipe, drinking the good water, out of – the cup” (fig. 23).[37] Sara Cedar Miller has discussed the “water-cure establishments” of the 1860s and the assumed health benefits of Central Park water, as well as Bethesda Fountain as the social and spiritual centerpiece of the Park.[38] For Miller, as for others of his time, water was linked to the Christian rituals of baptism and spiritual healing. It was a theme that he had invoked in several of his other works. For example, a sketch now in the collection at the York Historical Society depicts a highly ornamented baroque fountain (fig. 24). Water pours from decorative spouts and from a horn clutched by a nude figure, which is flanked by couples in wedding attire. Should the viewer overlook the ritual significance of water while taking in this luxuriant scene, Miller provides a small drawing, to the right, of Christ and the woman of Samaria at the well. In John 4:1–45, Jesus is tired from his journey and rests by the well. A Samaritan woman comes to draw water, and is shocked when he, a Jew, asks for some to drink. Describing the living water of everlasting life and the never-ending fruits of the harvest, he begins his mission on earth. Arching above the picture is a banner held by cherubim, emblazoned with the phrase “Water of Life to drink.” Below, Miller wrote: “The Well of water, Springing up into Life, who drinketh of this water Shall thirst again, Give me to drink.”[39] Another drawing, also in the collection at York, depicts a fountain in a luxuriant garden setting, flanked by tall, stylized trees, and by symmetrical weeping willows that mirror the arcs of water (fig. 25). Figures meander in the foreground and further back near a pair of horse monuments. The long German quotation is telling:

Learn how waters differ here from waters there,

Where the Creator is praised: there perfumes blend, others deep in ditches raised,

Up-flowing, shedding little tears of longing glowing;

They are streams of sweet delight, God to serve beseems.

There in higher air, scripture’s Truth speaks of Joy for e'er,

Along the streams of Life. Yes, where the fount of blessedness

Shines brighter still. There, now, free of strife, the chief shepherd’s grazing,

leads us to peace after weeks of weeping[40]

For Miller, earthly water pours forth from the heavens (“streams of sweet delight” and “streams of Life”) as a reminder of his Creator.

This sentiment of water as a life-giving and spiritual elixir is prevalent throughout Miller’s Central Park album. Miller draws two walkers, both following a path in a wooded grotto in the ramble (fig. 26). One of the figures heads toward steps leading to a small waterfall in a rocky cave while the other steps under an arbor entwined with grape vines. In this instance, both the “little spring of water coming out of the Rocks” and the “arbor of wild grape . . . vine’s [sic]” have a religious significance, the latter signaling the sacrifice of Christ and the former the renewal that baptism brings. In the text, Miller is at his most explicit in his re-casting the patch of nature in the middle of New York City as a New Jerusalem, again in the words of Luther:

Bounties of the Earth beneath, wealth and Substance, Sure, he hath;whilst his eye with joy Shall See In his fair posterity, children’s children, all the while, happy in a father’s Smile. then, departing, he at last, when the Scenes of earth are past, from that pure and peaceful Stream of the new Jerusalem, he Shall drink, nor limit know, In that fountains boundless flow, he Shall join the Saintly band – pilgrims passed to Canaan’s land, where in full fruition dwell God’s redeemed Israel.[41]

The passage clearly situates specific features of Central Park (the stream and fountains, the fecund landscape) as an earthly mirror of the heavenly city. The familiar words of Luther transform a “foreign city” into—rather than the picturesque sites of Germany, in this case—a version of the universal “home on high” that Miller is constantly striding toward.

Miller saw his wanderers and walkers as emblematic of the human condition, with the park as a reminder of redemption. By re-casting the sites as sacred, he invited his readers to explore the park with a mindful eye. Locating the divine-through-nature stems from ancient thought, was re-cast by Augustine, and can be traced through nineteenth-century thought and philosophy. David Morgan has recently cited the examples of “the beauty of nature as the signature of an underlying spiritual reality; the spiritual in art; the revival of religious art; and the quest to use art to plumb the national soul.”[42] Miller, as spiritual guide to Central Park, engages with each of these ideas. He locates divine presence in the beautiful and picturesque, unabashedly shifts the meaning of secular scenes to have a spiritual significance, and demonstrates, through a religious patriotism and deep appreciation of public space, his pride in the nation where his father settled as a German immigrant a generation before. The park welcomed him as it would go on to welcome others. After all, we are all “pilgrims and strangers” on earth, and within the sacred spaces Miller located in New York’s Central Park.

[1] Henry L. Fisher, “Lewis Miller,” York Daily, September 29, 1882.

[2] Lewis Miller, “Chronicles of York, 1790 – 1870,” as quoted in Preston Albert Barba and Eleanor Barba, Lewis Miller, Pennsylvania German folk artist (Allentown: Pennsylvania German Folklore Society, 1939), 12–13.

[3]Therese O'Malley, “Lewis Miller’s View of American Landscape,”Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013).

[4] Linda Kay Davidson and David M. Gitlitz, “Reformation and Pilgrimage,” in Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland: An Encyclopedia (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2002), 2:514.

[5] Ibid., 513.

[6] Victor Witter Turner and Edith Turner, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996), 241. John F. Sears has also invoked the Turners to support his argument that tourism and pilgrimage “both promise spiritual renewal through a contact with a transcendent reality (the shrine of the saint or the sublime waterfall). Sometimes they offer the hope of physical regeneration as well through the aid of a sacred or medicinal spring. A tourist, wrote the Turners, is ‘half a pilgrim, if a pilgrim is half a tourist.’” John F. Sears, Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 5–6.

[7] Dee Dyas, Pilgrimage in Medieval English Literature, 700–1500 (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: D.S. Brewer, 2001), 8.

[8] Simon Coleman and John Elsner, Pilgrimage: Past and Present in the World Religions (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 6.

[9] Translated by Emily Pugh.

[10] Goethe went so far as to mention how much better the real pilgrims looked, en route to Rome or Compostela, in their habits “than the trailing taffeta habits we usually wear when we appear as pilgrims at our fancy dress balls . . . the wide cape, the round hat, the scallop shell, that most primitive of drinking vessels, everything had its meaning and immediate use.” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italian Journey, ed. W. H. Auden and Elizabeth Mayer (London: Penguin, 2004), 75.

[11] In a different context, Christopher Wood has characterized all pilgrimages as re-enactments of those that had come before, noting that “the point of interest is where the reenactment slips a gear – where there is a medial shift, a transfer of meaning from original building to replicated building to painted building.” Christopher S. Wood, Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 238.

[12] North American Bibliographic Institution,Our Globe: A Universal Picturesque Album (Philadelphia, 1868), 191–92, last accessed April 11, 2013, http://archive.org/details/ourglobeuniversa00nortuoft.

[13] The original text reads, as follows:

In situations at once elevated and solitary—upon the summit, for instance, of a lofty mountain— our thoughts assume a more serious tone, and are apt to elevate themselves in a measure not disproportioned to the great objects which the eye then presents to our contemplation, filling us with a nameless silent satisfaction free from all alloy of sensual feeling. Common and earthly sentiments are left with the world below when man ascends above the ordinary dwelling places of men. Sorrow, therefore, and pain of heart have in all ages fled for relief and consolation to such places of refuge. The Bible tells us that the royal mourner David, and the prophets, sought the mountains in the hour of affliction. Such causes have always made them the refuge of men seeking, in retirement from the world, to forget all earthly cares, and to devote themselves to contemplation and self-examination. In the earlier ages of Christianity, numbers withdrew into the mountains, to apply themselves to study free from the interruptions which, in society, they were continually exposed. The peacefulness of their new abode wrought imperceptibly upon their souls, and they found among the rocks a heaven of the mind, from which they looked back, only with aversion or pity, on the scene of turmoil which they had left. They remained in their solitudes, and lived and died as hermits. On many of the spots remembered as places in which such anchorites had dwelt, chapels, churches, or convents were built in after times; and hence comes it that we often find, upon the loftiest elevations of most inhospitable regions, splendid and large religious edifices.

Note also the memorializing aspect of the end of Miller’s quotation: “O – withdrew into the mountains – as hermit in Solitude, in the hour of affliction and dwell their. That So, when I am passed away, And in my grave lie Slumbering cold – with fond remembrance friends may Say, his heart, his – heart grew never Cold!” Lewis Miller, View in Giles County, VA, in “Sketch Book of Landscape’s [sic] In the State of Virginia,” (1853), 41, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, VA.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Michael S. Bird, O Noble Heart/O Edel Herz: Fraktur and Spirituality in Pennsylvania German Folk Art (Virginia Beach: Donning Co., 2002), 9.

[16] Ibid., 10.

[17] Thank you to Joseph Hammond for fruitful conversations about this attribution. For a more in-depth analysis of the revival of the notion of interior pilgrimage as set forth in the works of St. Teresa of Avila, and the use of her image in the art of the early-to-mid nineteenth century, see Kathryn R. Barush, “'Every Age is A Canterbury Pilgrimage': Art and the Sacred Journey in Britain, 1790–1850” (PhD diss., University of Oxford 2012).

[18] Robert Bishop, Lewis Miller’s “Guide to Central Park” (Dearborn: Greenfield Village and Henry Ford Museum, 1977), 1.

[19] Frederick Law Olmsted to Board of Commissioners, Letter of Resignation, January 22, 1861, in Frederick Law Olmsted, Civilizing American Cities: A Selection of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Writings on City Landscapes, ed. S. B. Sutton (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1971), 13–14.

[20] Ibid. For the relationship of Lewis Miller’s art to the photography found in other contemporaneous guidebooks see, in this issue, Therese O'Malley, “Lewis Miller’s View of American Landscape” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013).

[21] David Morgan and Sally M. Promey, eds., The Visual Culture of American Religions (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001), 17.

[22] Lewis Miller, “Chronicle of York, PA,” 2, York Historical Society, York, Pennsylvania.

[23] Belden C. Lane, ed. Landscapes of the Sacred: Geography and Narrative in American Spirituality (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 25; and Louis P.Nelson, ed., American Sanctuary: Understanding Sacred Spaces (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006), 6.

[24] Lewis Miller, “Guide to Central Park,” 1.

[25] Paula A. Mohr, “God in Gotham,” in Nelson, American Sanctuary, 41.

[26] Turner and Turner, Image and Pilgrimage, 250–54.

[27] Mohr, “God in Gotham,” 41.

[28] “How New York Breathes on Sunday: The Working Men of the Metropolis Filling Their Lungs for the Week,” New York Herald, July 30, 1860.

[29] “The two-path theme was used by Johan Tauler (1300–1361) [German Dominican mystic and preacher] in his description of the alternative routes which present themselves to the pilgrim . . . Tauler’s development of this theme consists of a systematic integration of several scriptural sources, including passages from the first Psalm: 'For the Lord knows that way of the righteous, but the way of the wicked will perish' (Psalm 1:6). Tauler’s 1680 text and engraving of the two roads, one leading to eternal life, the other to damnation, would appear to have inspired numerous Pennsylvania printers and artists.” Bird, O Noble Heart, 107.

[30] Miller, “Guide to Central Park,” 33.

[31] Ibid., 52.

[32] Mohr, “God in Gotham,” 49.

[33] See especially A. L. Rawes, “Byron’s Confessional Pilgrimage” in Romanticism and Religion from William Cowper to Wallace Stevens, ed. Gavin Hopps and Jane Stabler (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006),121–36.

[34] George Gordon Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage,canto 3, st. 1, The Works of Lord Byron (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1842), 34.

[35] Miller, “Guide to Central Park,” 31.

[36] Mohr, “God in Gotham,” 49.

[37] Miller, “Guide to Central Park,” 51.

[38] Sara Cedar Miller, Central Park: An American Masterpiece (New York: Harry N. Abrams Publishers in association with the Central Park Conservancy, 2003), 63–65.

[39] Miller, Sketchbook, York Historical Society, York, Pennsylvania.

[40] Ibid., 158. Transcription by Emily Pugh; translated by Genese Grill. Like his English, Miller’s German (likely copied from an earlier, possibly early eighteenth-century book or manuscript) is fragmentary. However, the waters as earthly remembrances of Creator/Creation is apparent in the text.

[41] Martin Luther, Psalm 128, “The Happy Man,” in Hymns of the Reformation, ed. Author of “The Pastor’s Legacy” [Henrietta Joan Fry?] (London: Charles Gilpin, 1845), 99, http://books.google.com/books?id=gv5LAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA99, as quoted in Miller, “Guide to Central Park,” 5.

[42] James Elkins and David Morgan, Re-enchantment (New York: Routledge, 2009), 35.