The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

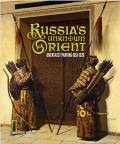

Russia's Unknown Orient: Orientalist Painting 1850–1920

Groninger Museum, Groningen, The Netherlands

December 19, 2010 – May 8, 2011

Russia’s Unknown Orient: Orientalist Painting 1850–1920.

Edited by Patty Wageman and Inessa Kouteinikova, with contributions by Olga Atroshchenko, Irina Bagdamian, Vladimir Bulatov, Inessa Kouteinikova, David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye and Karina Solovyeva.

Groningen: Groninger Museum/ Rotterdam: Nai Publishers., 2010.

224 pp., color illustrations; black and white illustrations; index; time-line.

€29.50 (paperback English edition)

ISBN-10: 9056627627

ISBN-13: 978-9056627621

The Groninger Museum presented last year the exhibition entitled Russia's Unknown Orient: Orientalist Painting 1850–1920. The show introduced largely unfamiliar Russian orientalist painting to a broad Western audience. Between 1850 and 1920, Russian painters depicted the neighboring regions such as Uzbekistan, Georgia, Armenia, and the Crimean peninsula with various points of view according to their role. There was the testimony of the traveler on pilgrimage to the Holy Land, the depiction of holy places, the scientific description of a land's geography for bellicose purposes, or the war artist's rendering of battles and victories. As a result, there were many a great amount of colorful paintings, but also black and white photographs and geographical maps, representing the more scientific aspect of Russian Orientalism. All this was presented on vibrantly colored walls that added to the variety of material and provoked a rich aesthetic experience for the visitor.

The title of the exhibition exploded the idea of the unknown or dismissed character of Russian Orientalist painting. This is partly due to Edward Said's publication Orientalism, where the author criticized the Western Manichean representation of the East as means of subjugating it. Said’s work gave name to a whole literary school defined by this parameter, and the association of Orientalism with art was soon applied by art critics. The focus on Great Britain's and France's orientalist legacy though, led to the dismissal of Russian Orientalism. The Groninger Museum show, therefore, should be seen as a vindication of this legacy, and secondly as a celebration of the work of Vasily Vereshchagin (1842–1904). Vereshchagin, an artist trained in Paris by Jean-Léon Gérôme, recorded the horrors of the war at Samarkand and Turkestan. The exhibition included forty of his art works (far more than the average three per painter) and crowned Vereshchagin as the show's hero, inducting him into the academic orientalist painting canon. The advertising image for the show The Doors of Timur by Vasily Vereshchagin prepared the visitor for the discovery of the “unknown” (the mysterious closed door) as well as for the work of the hero Vereshchagin (fig. 1).

Orientalism though had a specific character in Russia. The Russian people were under Mongol rule for 250 years (1237–1487) and proudly claimed Asian roots in aristocratic lineages until Peter the Great took a decisive turn to the West. He moved the new capital of the empire to St. Petersburg at Russia's Western edge and adopted the European manners and fashions at the end of the eighteenth century. On the other hand, the absorption of Crimea (Muslim territory), added to the Russian Asian heritage, led to suspicion within European aristocratic circles and distanced Russia again from the West. Furthermore, the Slavophile movement born in the 1830s rejected the West for its materialist and vulgar character, in opposition to the spirituality and communality that dominated Europe’s Orthodox Slavic East (18). The resulting hybrid Russian identity was actually not an issue until Peter the Great’s bid for Westernization raised the question, thus highlighting the paradoxical character of Russian Orientalism (and probably affected Said’s dismissal of the Russian case). This paradox was reflected in the exhibition, which began by displaying the Eastern “other” as cruel and savage and concluded by including an Armenian artist (the other) in the show (figs. 2 and 3).

The exhibition started in a pink room where two paintings hung at each side of a door (fig. 4). Here, “the other” appeared in both art works as a morally inferior being. Alexander Russov's (1844–1928) Bought for the Harem showed a pale-skinned woman lying on the floor in the attitude of crying while an unscrupulous dark-skinned man grinned at her in an arrogant way. The next painting, Stanislaw Chlebovski's (1835–1884) Drama in a Harem, rendered a pale-skinned woman sleeping in a richly decorated bed while several men walk silently in the room; the attitude of the dark-skinned man who approaches on tiptoe, in combination with the painting’s title, made viewers think the worst. Symptomatically, this sort of painting did not appear again in the exhibition. Was the presence of such stereotypical themes of the “other” a must for the visitor to feel at home when thinking about orientalist painting? Or was it an appeal against cliched images? In any case, they remained at the entrance hall, thus not mixing with the rest of the art works and being distanced from Russian Orientalism.

The wall text in the entrance hall was displayed on the side wall (fig. 5). Although this fact might seem superfluous, it appears key in an exhibition where there was no more text to read than the section’s title in every room. The curator Inessa Kouteinikova made a clear bid for the sensuous where the bright colors of the walls dialogued with the colors of the paintings on display. To counterbalance this shortage of information, the museum offered at the entrance of the exhibition a little booklet with a selection of art works from every room, each explained in a few lines. Moreover, the visitor was provided with an image collector called “GM collector,” which was activated when holding it against a box with a chip on the wall next to a painting and which sent the picture and the related information of that artwork to a personal session at the Groninger Museum’s website (figs. 6 and 7). The convenience of such a device is remarkable due to the possibility to create a personal on-line exhibition catalogue at home; the displacement of the art works themselves due to the passion for collecting the images manifested by the visitors, however, was detrimental to the GM collector’s success.

The first room, titled “Imagining and Depicting the Orient”, had an oval shape and was painted in a yellowish tone (fig. 8). The large painting Keinoba from Grigor Sharbabchian (1884–1942) appeared here as a celebration of oriental festivities and rituals. Two market scenes hung next to the two mausoleums from Ivan Kazakov (1883–1935). Besides this, there were three renderings of the Sher-Dor Madrassah temple in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. The popularity of this last motif was not casual considering the Russian annexation of Samarkand in 1868. In this context, the painting from Mikhail Belaevsky (1893–1930) and the two paintings from Lev Boure (1877–1943) all on the aforementioned temple could be seen as victory trophies under the imperialistic drive of Orientalism.[1] As the title of the room announced, there were imaginary images as well. Those were the dream-like paintings of Vardkes Sureniants (1860–1921) and Andrei Roller (1805–1891), who composed the Gardens of Chernomor in 1842 with a fairy-tale palace on the right side and exotic trees and plants all around the building. The marvelous colors added to the magic perspective and the fantastic elements created the suitable set design for the opera Ruslan and Lyudmilla at the Bolshoi Theater in St. Petersburg.

The second room was devoted to the geographic research conducted on the neighboring lands. This section was called “Expeditions—Constructing the Future” and the red color on the walls made the maps and drawings stand out magnificently. The earlier maps on display showed scientific and military interests with very precise political and geological borders (late eighteenth century to mid-nineteenth century). A map made in 1866, however, displayed ethnographic curiosity as well; the Map of Russia and the Tribes That Inhabit Her represented twenty-one “tribes” in little drawings around the great map in the center (fig. 9). This piece highlighted the ethnographic diversity of Russia while it stressed its imperial power in diverse and far away provinces. The rest of the works in the room consisted of a series of watercolors from Nikolai Karazin (1842–1908) for the Trans-Caspian Railway (fig. 10). As the exhibition booklet stated, the series showed the exotic new areas of the Russian empire that the railway company managed to connect in the 1880s.[2] If the military first used the railway, industrial and commercial interests in it quickly followed and thus provided the watercolors with a clear advertising character.

A little green room came next, with the title “Allegories—Confronting the Past”. The works that hung there were indeed allegorical, although rarely confrontational. Paintings such as Catherine the Great making a tour on a horse-car preceded by the angels, Ivan III tearing up the Khan’s Charter, or even Prince Mikhail Chernigovsky’s role at the grand machine painted by Vasily Smirnov (1858–1890) followed the Western canon of history painting (fig. 11). This green space led to a greater room that represented the Russian orientalist hero Vasily Vereshchagin’s work in full bloom (figs. 12 and 13). This section, “Vereshchagin—The Painted Voyage”, consisted of a long rectangular space with lavender-toned walls. The painter joined the Russian army during its conquest of Central Asia between 1867 and 1869 and recorded the exotic wonders he found on the way, like Samarkand, where he fought and was injured, and for which he received the fourth class Saint Joris-Cross.[3] The Kirghiz people appeared well represented in this room too, with depictions of their daily life at the camps (fig. 14). This last group of paintings were shown in London (1873) and Moscow (1874) at the artist’s solo exhibition devoted to the Turkestan.

“Vereshchagin—A Window to the Orient” was the core section of the exhibition. This room displayed Vereshchagin’s pacifist legacy with a whole series of paintings showing the horrors of war. This body of work hung in a dark room with red-painted walls that invited the visitor to engage in the reflection Vereschchagin wanted to foster (fig. 15). The artist believed in the power of art to move consciousness and change the world, and with this idea he created the Poèmes Barbares series. This series consisting of seven large canvases which were intended “...to be 'chapters’ in a narrative about a successful raid by the Emir of Bukhara’s forces on a tsarist unit.”[4] It began with an espionage scene and it went through the assault, battle, native victory, and final celebrations. The last painting though, presented a universal teaching as a sort of conclusion. Entitled Apotheosis of War, a pile of skulls laid in the center of a deserted entourage (fig. 16). The artist wrote on the frame: “Dedicated to all great conquerors, past, present and future,” condemning bellicosity by showing the only result that war obtains. The paradox of the pacifist war artist suggested somehow the tragic character of the exhibition’s hero and introduced the first of a series of smart counterpoints in the canonical orientalist discourse.

The next room, entitled “Biblical Orient”, had an overall lighter character with soft-toned paintings and drawings hanging on blue-painted walls (fig. 17). Vasily Polenov (1844–1927) took the lead in this room with the majority of the art works coming from his hand. He specialized in landscape painting and visited the Middle East and Palestine twice, in 1881 and in 1899. As well as his contemporaneous compatriot Vereschchagin, Polenov went south to make sketches for future biblical paintings that would capture the topography in precise renderings. In between his many drawings, Polenov’s paintings were especially captivating (fig. 18). According to Olga Atroshchenko, the artist faced the challenging atmospheric conditions of Palestine using a la prima technique, applying unmixed colors directly to the canvas:

He tried to instantly capture the scenery that so captivated him, to communicate the particular atmosphere—in a physical sense—of the place, to transmit the perception of how clear the air was there in the mornings, how the heat would set in by noon, and the soft shades the sky would develop by sunset. (136)

Indeed, the paintings strongly evoke a sense of place at the sacrifice of Biblical subject matter, which seems almost an excuse for the painting to render the beautiful landscapes that so attracted the artist.

A display of “Early Orientalist Photography” could be seen in the seventh room. This ochre-colored space put the most scientific body of work on display (fig. 19). Orientalist photography developed in Russia hand-in-hand with cartography since the early photographers were graduates of the Military Topography School. The study of the life and habits of people inhabiting far lands could be used to establish principles of conduct on the battlefield. Pictures of people at work, soldiers during a training, or group portraits of the village leaders hung next to each other (fig. 20). There were also drawings of native people from different lands in their traditional costume, showing a clear ethnological interest far removed from the pure military drive (fig. 21). This interest probably led to the organization of the Ethnographic Exhibition in Moscow in 1867, an exhibition that showed the urban Russian audience the rich variety of peoples and cultures who coexisted under Russian political control. As Karina Solovyeva puts it, the Moscow exhibition “amounted to a real discovery for Russian society. . . and made a definite contribution to the development of the theme of the East in Russia's artistic tradition.” She later adds:

It was the documentary precision, artistic expression and information-rich nature of these photographs that defined this highly informed perception of vibrant and diverse cultures and traditions, a worldview in which Muslim and Christian societies lived in harmony side by side (64, 66).

Entitled “A View from Within”, the eighth room displayed the work of the “Masters of the New Orient” (fig. 22). Some Russian and Uzbek artists living in Uzbekistan formed this group around the figure of Alexander Volkov (1886–1957) in the 1920s to devote their art to the new Turkestan. The industrial and commercial development of Central Asia attracted many Russians in the beginning of the twentieth century. Artists went there specifically to look for new artistic sources. The ancient Eastern traditions, the miniature technique, the ornamental painting, and the applied arts all greatly influenced this group. This resulted in highly colorful depictions of the Uzbek people’s life rendered with the oriental spirit. The exuberant body of work from several artists stood out even more thanks to the bright green walls that gave the room an overall celebratory character (fig. 23). Alexander Nikolaev (1897–1957), one member of the “Masters of the New Spirit,” was an expedition artist who traveled with the army. Once settled in Uzbekistan he specialized in paintings of angelic boys (fig. 24). The mixture of sources, from Renaissance al fresco painting to the sinuosity of Islamic art, created exquisitely delicate paintings with Uzbek themes.

Presented on strong lavender-colored walls, the ninth room exhibited the section “The Kazan Station—Bridging East and West” (fig. 25). The Kazan Railroad Station was designed by architect Alexey Shchusev (1873–1949). As the railroad went deep into Russia, the architect planned the station as a “. . . panorama of Russia's history and its rich culture” (191). Shchusev was interested in the Russian Orient for years and attended an archeological expedition to Central Asia to study famous architectural monuments (1894–1897). The station seemed to be the conclusion of that expedition: he chose specific architectural and decorative elements from all the buildings he saw and created an homage to Russia’s orientalist heritage. In addition to this, he commissioned a series of mural paintings to decorate the interior of the station. Zinaida Serebriakova (1884–1967) developed a sequence of sensuous female nude paintings, titled Siam, Turkey, Japan, and India, trying to represent the essential character of every land (figs. 25 and 26); Evgeny Lanseray (1875–1946), a mural artist and master of perspective, painted the mural The Peoples of Russia (fig. 27). This masterpiece shows the embodiment of Russia to the left and that of Asia to the right. Although the attributes of Russia are those of a technologically further developed society (see the smoking-factories as opposed to the animals and harvest), both lands are represented by a young woman richly dressed and in a similar self-assuring bodily attitude, thus positioning the two cultures at the very same level.

A monographic selection of work from the Armenian artist Martiros Sarian (1880–1972) appeared in the last room. “Sarian's Orient—Working for Posterity” displayed Fauvist paintings hanging on blue walls (fig. 28). Sarian represented a transitional figure between the old and contemporary artists’s generation in Armenia by combining Oriental and Occidental artistic elements. In the beginning, his work was highly poetic with soft colors and fairytale-like motifs, then progressively it evolved into a Fauvist elaboration of portraits and still-lifes (fig. 29). The modernity of Sarian’s work and his transitional character between generations made him an uncontested representative of Armenian art. Moreover, Armenia's tormented past with its splitting and division between Persia and the Ottoman Empire was also affected by the expansion of the Russian empire. The hybrid culture of Eastern and Western elements that Armenia was able to create, and the paradoxical presence of this room in the show, made Sarian’s section the perfect choice for the ending of the exhibition.

Russia’s Unknown Orient was an instructive and enjoyable exhibition. The presentation of a contested Orientalism, offering an alternative model to the seemingly unmovable authority of Western Orientalist painting, was as refreshing as necessary. Here, the visitor could see the most negative (and probably fantastic) depictions of “the other” oriental at the entrance and then forget them immediately when viewing the rest of the show. The initial presentation of the Orient as a fantasy land (room 1), turned to a more scientific character with the display of maps; and it then went through the smart and pessimistic vision of Vereschchagin (rooms 4 and 5), who paradoxically denounced war while being an Orientalist war artist. The show further depicted the Biblical Orient (room 6), and then the anthropological rendering of the oriental peoples with the collection of photographs taken of them (room 7). The next section of the exhibition focused on the work of Russian artists living in the Orient and adopting oriental influences in their work (room 8), culminating in the following section featuring the Kazan station as a bridge between the East and the West, and artworks blurring the boundaries of these two worlds (room 9). Finally, the inclusion of an oriental artist who brought Western modernity to oriental painting seemed the logical ending to an all inclusive and sensitive exhibition. The exhibition gave voice to both orientalists and “the other” in a beautiful and colorful show with a clear bid for the visual.

The exhibition catalogue provided the visitor with the information needed to understand Russian Orientalism in all its complexity (fig. 30). It included a survey of Russia’s history and of its colonial project, with more or less a chapter on each section of the exhibition. The question remains as to what extent the visitor understood the whole point of Russian Orientalism by only viewing the exhibition (and without reading the catalogue). The section titles were certainly helpful, but not enough to prevent the visitor from getting lost in a sea of colorful paintings and rooms while missing the argument. In conclusion, the exhibition smartly presented a contested Orientalist canon that greatly added to the development of the orientalist discipline, and at the same time, pleased the eyes with an appealing display of works in a colorful atmosphere.

Alba Campo Rosillo

Art Historian

info[at]albacampo.com

[1] Note that Vereshchagin painted the same site as well, Sher-Dor Madrassah on the Registan Square in Samarkand, 1869–1870 (State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow).

[2] Inessa Kouteinikova and Steven Kolsteren, Russia's Unknown Orient: Orientalist Painting 1850–1920, exhibition brochure (Groningen: Groninger Museum, 2010), 3.

[3] Ibid, 5.

[4] David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, “Vasilij V. Vereshchagin’s Canvases of Central Asian Conquest,” Cahiers d’Asie centrale 17/18 (2009): 179–209.