The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Introduction

The tourist and the invalid, both seeking the sun and warm nature, today stop struck in admiration before all these southern marvels, the one to be inspired by this source of poetry and grandeur, the other to breathe health and life amid this promised land, under constant blue skies. Where indeed can you find hospitality at once compatible with both art and health?

– J. B. Girard, Cannes et ses environs, 1859[1]

As early as 1859, the tourist-writer J. B. Girard characterized France's Mediterranean coast as the unique meeting point of the aesthetic and the therapeutic. Girard emphasized that the appeal of towns like Cannes for the artist and the invalid[2] was not to be located in its glamorous ballrooms or casinos, but rather in its natural grandeur. By 1887, when the poet Stéphen Liégeard named the region "la Côte d'Azur,"[3] he did so using a well-established aesthetic framework; this was a landscape of color: an azure-colored coastline.[4] In 1964, the art historian Pierre Cabanne described the region as not simply beautiful for the visitor but transformative for the artist's aesthetic sensibilities:

For some, the South of France represents a welcoming climate, a form of pleasant existence among landscapes that one customarily calls divine and that, moreover, they are; the mildness of the atmosphere, the beauty of the sites, the purity of the sky have made the Côte d'Azur a kind of privileged stay, an exceptional place of nature. For others, it has transformed their vision; the primacy of light and of form on colors has rendered the painter more attentive to structure, to the morphology of things.[5]

What emerges from Girard's and Cabanne's statements is a sustained and normalized belief, spanning over a hundred years, in the transformative powers of the Côte d'Azur on the bodies and minds of artists and invalids, two forms of tourists. This article explores shared aesthetic and therapeutic perceptions of this region during the fin-de-siècle, approaching them through a case study of the neo-impressionist artist and chronic arthritic, Henri-Edmond Cross (1856–1910). Like Eugène Boudin (1824–98), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), and Louis Valtat (1869–1952), he was one of several vanguard artists of the late nineteenth-century who travelled south, to France's Mediterranean coast, for his health.[6] Cross settled permanently on the Côte d'Azur from 1891 until his death in 1910, and those two decades are crucial for the few art historians who have approached his oeuvre.[7] The year 1891 marked both his move to the Maures region of the coast, a choice made for reasons of health, and his conversion to neo-impressionism.[8] Cross, like Renoir, has been discussed in art-historical literature as both a modern artist and a chronic arthritic living on the coast. Those two categories have been perpetuated throughout his historiography as fundamentally intertwined, and Cross has been described as a painter suffering for his art in the face of physical anguish—a narrative of "triumph over adversity."[9] With Cross, indeed through Cross, I offer a new, alternative history of the Côte d'Azur approached through the body of the French artist-invalid, accessed through his perspectives, practices, and representations.[10]

Through texts and images, this article analyzes Cross's life on the Côte d'Azur as a case study, not a lionizing biography, bound to contemporaneous medico-geographical perceptions of the transformative or "imprinting" power of southern climates on northern bodies, especially those with an illness or of delicate constitution. Paintings of the last five years of Cross's life, exemplified by representations of female nudes set within the artist's immediate surroundings, stand as metaphor, product and producer of such perceptions. This article is heavily concerned with primary and secondary sources concerning Cross's biography, medical literature, and invalid perceptions of place, exploring their words and meanings. By doing so, I seek to provide a new, medical lens through which to contextualize the historical significance of the Côte d'Azur during the fin-de-siècle for its visiting artists and invalids.

Imprints

Perceptions that climate has a direct influence on bodies are of ancient, Hippocratic origin. If we look to medical geography of the nineteenth century, the relationship between body and place becomes particularly well-defined. Texts during the period by physicians and geographers explained that climate had a profound, transformative power over the body's development, manners, well-being, and thoughts. To put it simply, they believed that the body was quite literally imprinted by the environment it inhabited.[11] In a work of 1843, J. C. M. Boudin wrote, "medical geography has as its object the knowledge of modifications imprinted on the organism by the influence of climates, and the study of laws presiding over the distribution of illnesses throughout the diverse parts of the globe."[12] Earlier, in 1821, François Foderé viewed the appearance, temperament, habits, and manners of the peoples of the Alpes-Maritimes region as intimately tied to its climate, no different from the region's other "natural" products: "If we have seen that plants and animals carry the imprint of climate, then man – child of the earth as the others – cannot deny this maternal influence."[13] This is echoed by Charles Lenthéric in the epigraph, from his popular 1878 book, Greece and the Orient in Provence:

The life of man is, in effect, intimately tied to the nature of the environment in which he lives; his manners, his customs, his migrations, his industry, the most minute conditions of his existence depend directly on the physical make-up of the surface on which he is active.[14]

This concept of humans "carrying the imprint of climate" implied that local populations were physical manifestations of that environment—products grown from its soil and raised in its climate. As such, they served as signs of the salubrity of that climate, and medical geographers looked to their appearance and health for indications of the site's suitability to treat certain illnesses.[15] As late as 1901 these perceptions were still current; E. Staley, for example, in a popular physical culture magazine, visually compared the working women of the coast to its characteristic "strong-limbed" aloes (figs. 1, 2). Both human and plant are perceived as topographic products nurtured by the same climate, even the same soil, their appendages comparable in structure and form. Staley found their back-breaking labor noble and admirable, rallying his readers to emulate their strength and stamina. The visual comparison may appear to us surprising, even ridiculous, but the notion that the temperament and even physiology of certain ethnic groups were strongly tied to their particular environments is neither new nor extinct in the popular imagination. In his 1847 tourist handbook of France, John Murray described the temperament of southern locals as fundamentally driven by the Mediterranean sunlight: "The character of the people appears influenced by the fiery sun, and soil which looks as though it never cooled. Their fervid temperament knows no control or moderation."[16] Even today such views remain firmly intact, that southern peoples are characteristically passionate, temperamental, and brash. That Staley made the connection between southern bodies and southern climate literal by means of a physical comparison was, by the fin-de-siècle, a matter of common sense.

Significantly, if climate were responsible for the physical development of humans born and raised there, it could transform the external and internal structure of the visiting body, enabling physicians to utilize climate in a therapeutic context, that is, climatotherapy (cure by a "change of air"). Indeed, climate was perceived to be all the more powerful on marking or "imprinting" the invalid, since his or her body was in a delicate or weakened state through illness.[17] The invalid's body was understood as more receptive to and more quickly affected by the influence of a new climate than were healthy bodies. This was a fundamental principle underlying the widespread, international use of climatotherapy throughout the nineteenth century. The statements by Boudin, Foderé and Lenthéric are but a few exemplary cases of medical geographers and physicians interested in the effects of climate on man, and they shared a common scientific view in which the invalid's experience of place was distinguished from that of the healthy, "normal" or ordinary tourist.[18] Alain Corbin has argued that the invalid was a particular and peculiar figure of the nineteenth century, one who learned to develop an acute awareness of physical elements and their effects on the body:

With one voice, physicians, poets, and philosophers all urged greater preoccupation with and attention to self. The figure of the invalid that emerges from this convergence reveals the intensity with which coenaesthetic preoccupations were to obsess the leisured class in the nineteenth century. At the seaside holiday, even more than in the humidity of the spas, detailed behavioural patterns were codified as part of the quest for well-being. Invalids learn to savour the pleasant sensations provided by the smooth functioning of their bodies: good circulation, refreshing sleep, and renewed appetite.[19]

Corbin's use of the word, coenaesthetic (the general awareness of one's own body), is a useful way of conceptualizing how sensations were experienced as part of a therapeutic program. Climatotherapy was a medicalized and deeply naturalized way of perceiving place, and a plethora of tourist and medical literature exists from c. 1850–1920 about the Côte d'Azur as an appropriate site for it.[20] Physicians advised the chronically ill, like arthritics, to visit the region every winter, if not longer.[21] Chronic illnesses such as arthritis thus required continuing maintenance. As Corbin has made clear, the curative program or regime was well-structured, organizing and ordering not only the patient's therapeutic practices but his or her very lifestyle. In this context, Henri-Edmond Cross emerges as a particularly relevant case of a chronic invalid and active artist living on the Côte d'Azur when such perceptions of the imprinting, transformative powers of the region had become embedded within the popular imagination.

Cross: Artist-Arthritic

Cross is a fascinating example of an artist-invalid painting and therapeutically utilizing the Côte d'Azur, and has a unique position with which to approach attitudes to a region perceived simultaneously as beautiful and curative.[22] His chronic arthritis, which affected his joints and his vision,[23] has been constructed by his biographers, his friends, and even himself as a catalyst to his image-making: from the early 1880s when Cross spent his winters in Monaco and was first struck by the light of the coast, as manifest in his Jardin à Monaco (1884, Musée de la Chartreuse, Douai); to 1891 when he simultaneously moved permanently to the coast for his health and took up a neo-impressionist style (first in the Portrait de Mme H. F., 1891, Musée d'Orsay, Paris); to the early 1900s when his constant struggles and frustrations of living with painful inflammations affected his ability to paint; and finally to his untimely and painful death, due to cancer, in 1910.[24] Of pain, Isabelle Compin, the authority on Cross, wrote in 1964:

The acute suffering in his joints and his eye troubles, which he endured with courage, were all the more difficult for him as they rendered work impossible and such forced inaction was demoralizing. In this way, the torments of the body added to those of the mind. But when his health again improved, then, with the resources of his aiding will-power, he used this time of respite to its maximum and, as if to compensate for the painful, overwhelming periods, let blossom his vitality, long constrained. Moreover, he lived these moments of peace with an eagerness and an increased fervour because he knew them threatened and sensed their brevity.[25]

This would be echoed over forty years later, by art historian Claire Maignon in 2006:

His paintings of the final years overtly celebrate the captivating body of woman as nymph, in symbiosis with nature, blending into the cork woods. The lemon tints become sharper, the orange tints incandescent. The poetic exaggeration of the harmony of colors may well have been an escape for the painter from the gnawing pain which for decades had prevented him from working in peace. Now very frail, he therefore eagerly seized the rare moments of respite to give free rein to his coloristic verve.[26]

Note the lionizing rhetoric apparent in both passages, with the emphasis on physical pain and the courage to suffer it. Compin and Maignon have chosen to set up Cross's art as something done in spite of his arthritis, namely the physical restrictions it imposed on his lifestyle, or because of it, as an act of consolation and escape. No doubt their opinions were influenced by primary sources, namely the memories left by the artist's closest friends and his own letters. His friend and fellow artist, Lucie Cousturier (1876–1925), for example, described Cross's arthritis as a disability with which he constantly battled.[27] Cross himself made clear in letters to his circle how much his condition was ever-present in his daily existence. In a letter of circa 1906, he wrote to Maria van Rysselberghe, the writer and wife of Théo van Rysselberghe, that he had no memory of ever feeling fully recovered from illness.[28] Cross positioned himself as a chronic arthritic, perpetually unhealthy, and suffering from a degenerative condition. Not surprisingly, the issue of health dominates his correspondence, which has become the foundation of his biography.

My interest in the relationship between Cross's art and arthritis does not follow the lead of other art historians. Is it excessive to place such emphasis on a few inflamed joints? I believe, in fact, that not enough stress has been laid upon Cross's degenerative condition as a significant element of his artistic practice, and I do not mean in this sympathetic, sentimental, and even piteous vein. A chronic physical condition onset during his youth,[29] Cross's arthritis necessitated a permanent move south to the Côte d'Azur, various therapies (including electrotherapy, climatotherapy, medication, and massage)[30] and therefore ongoing self-regimentation and treatment. All of these were informed choices made by Cross which had significant impact on his life and career, as significant as the aesthetic choices he made as a methodical neo-impressionist painter. In his working method we find traces of the artist-invalid experiencing heightened sensations and receptivity to nature, and particularly so in relation to the late work.

The Late Work (1906–1910) and the Liberation of Facture

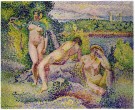

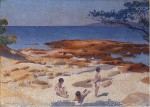

In early 1906, Cross took on a new project, hiring models to pose nude en plein air in the wooded brush near his house in Saint-Clair.[31] Studies like Étude pour Nymphes: Femme au chapeau, nu en plein air (c. 1906, Private Collection) became preparatory works for the finished painting, Nymphes (1906; fig. 3). Situated in dense foliage at the edge of the Mediterranean Sea, three female nudes are depicted as though either emerging as natural entities from the landscape or melting into it. Treating both figures and landscape with the same larger, squared touches typical of his later work, Cross abandoned the distinct contouring so apparent in L'Air du soir (c. 1893, Musée d'Orsay) and La Plage ombragée (1902, Private Collection), where the figures are clearly delineated from their environs. In Nymphes, the seated figure to the right is treated with inconsistent contouring, with virtually nothing to discriminate her reclining thigh from the forest floor. Accented with vertical, multi-colored touches of paint, thigh and ground appear sutured together. Equally, her right arm simply melts away with the cessation of fleshy pink tones. To the left, the standing nude curves her right arm, her hand resting on a branch. Green touches of paint, used to create shadow, overwhelm her arm and spread over to her collarbone. Lighter units of green contour the curvature of her breasts as well as the spine of her neighbor. Later that year in the autumn, he again employed a model to pose among cork oaks, trees particular to southwest Europe and northwest Africa, resulting in finished paintings like Le Bois (1906–1907; fig. 4). In this work, the nudes similarly appear to disintegrate into their southern surroundings, the lower limbs of the two standing nudes and the reclining nude simply cut off and blended into foliage. Like the myth of the Greek goddess Daphne, whose father transformed her into a laurel tree to escape the amorous advances of Apollo, Cross's late nudes appear as though in the process of being totally absorbed into the landscape, but through color and tesserae-like brushwork, a mosaic of color and light without contours. The dominant pinks and greens of both Nymphes and Le Bois indicate, too, that the works still adhere to the neo-impressionist principle of color complementaries. Despite Cross's use of relatively large, square markings, he has also continued to use a divisionist application of separate, individual touches of paint in the works. Whether the latter still allows for "optical mixing" for the viewer, as advocated by Ogden Rood and others, is questionable; their uniform size and squared shape resist that effect, and yet overall the paintings still shimmer and vibrate with light.

Exemplary of Cross's late work, Nymphes and Le Bois are perceived by art historians as expressing freedom of touch and freedom of imagination, liberated from the anguish of his physical reality. For example, his style has been explained by Isabelle Compin as changing subtly over the years, from his first works of the early 1890s, towards increasing freedom and imagination by the end of his life. In particular, she devotes discussion to two aspects of Cross's stylistic changes over the years: the liberation or enlargement of his touches of paint, namely the dots; and the liberation of color, especially with regard to his representation of sunlight. By 1906, his "late" period, Cross's subject matter would also change, now including mythological scenes, which Compin describes as the liberation of his imagination.[32]

In the early 1890s, when Cross first took up the neo-impressionist technique, he strictly adhered to employing small, round dots of relatively equal size and regular spacing. The Plage de Baigne-Cul of 1891-1892 (fig. 5) is a good example of Cross's early neo-impressionist execution. The dots are delicately, methodically, and evenly applied all over the surface of the canvas. But not only is the facture indicative of his early style, its color is characteristic of Cross's initial attempts to capture the sunlight of the region. Compin noted, "The tints Cross arranged in this way are pure but soft, because they are strongly blended by white. It is because, at that time, Cross tried to express true luminosity by blanching [décoloration], having noticed that deep light absorbs colors."[33] No doubt Compin was aware of the analysis by the artist and critic, Maurice Denis (1870–1943), who frequently wrote about Cross and noted this early tendency to blanch or whiten (décolor) the entire canvas in an attempt by Cross to "represent" rather than "reproduce" true sunlight (a reference, of course, to Denis's hero, Paul Cézanne).[34] In La Plage de Baigne-Cul, white dominates the canvas, more than half of the surface, including the depiction of sand as well as of water, especially along the shoreline. The effect is almost blinding.

Compin stated that, by 1895, Cross's interests began to change towards a new, more personal aesthetic research: "Fortified by the severe discipline of the neo-impressionist style, Cross searched from now on to surpass it. With it, as with the literal representation of nature, he would begin to take more liberties and that is how, from 1895 until 1903, his evolution towards a more personal art was made."[35] It is at this point that Cross abandons décoloration and instead represents the region's luminosity through intensified color harmonies. Compin views the change as fundamental to Cross's personal development. The execution of the dot changes as well, and although he continues to employ separate units of paint, they increase in size and allow for "an execution both freer and more rapid."[36] By the early 1900s, those touches of paint take on a square, mosaic-like effect.

Cross's work of 1906–10 is characterized by imaginative subject-matter revolving around female and, to a lesser extent, male nudes in the guise of nymphs and fauns set within the Côte d'Azur landscape, of which Nymphes is exemplary. The works have signaled to Compin a "will to give free expression to his personal fantasy."[37] Indeed, this must also be an iteration of Denis's initial comments; in 1910 Denis wrote that, in his late work, Cross "composed, and his liberated imagination called forth nymphs, fauns and dryads to fill the sculptural forms of Elysian landscapes."[38]

Situated next to the photographs featured in Staley's contemporaneous article (figs. 1, 2), Cross's late works, Nymphes and Le Bois (figs. 3, 4), make the integration of body and landscape literal on their painted surfaces. The union of figure and landscape in the late works is asserted over and over again in Cross's historiography. In the 1905 preface to Cross's first solo exhibition, the Belgian poet Emile Verhaeren (1855–1916) described recent work by Cross in which the forms of the figures melt into their surroundings, "where the human being, with her human flesh, seems to exist only as a plant full of fruits."[39] In 1964, this would be echoed by Compin, about paintings in which "the figures integrate into the landscape as vegetal and human forms, founded on the same arabesque lines, participating equally in the general rhythm."[40] And in 1998, François Baligand would write that "The…characters, under intense lighting, integrate with the landscape and participate in this communion with a generous and sensual nature."[41]

Such perceptions of Cross's increasingly liberated touch during his two decades on the Côte d'Azur remain firmly in place among art historians today.[42] This emphasis on "liberation," occurring repeatedly in the vocabulary, has therefore dominated both the primary and secondary sources, becoming a staple in his historiography. This narrative has implied that, despite two decades of unwavering interest in the coast's landscape and its intense sunlight, Cross progressively loosened or opened up a rigid, neo-impressionist facture towards increasing freedom, while also freeing his imagination to depict a world between fantasy and reality. But why should this be so? Why describe the stylistic changes throughout this oeuvre as a continuous trajectory towards increasing "freedom," a breaking away from the supposedly oppressive neo-impressionist theories of Seurat? To see these artistic developments as inevitable or natural, that the mature artist's style "naturally" becomes more experimental, looser, and freer, simply conforms to normative narrative strategies of art-historical literature.[43] More pertinent is to question what underlying assumptions have driven and continue to drive this narrative. I believe the narrative is, firstly, rooted in a widespread, long-standing belief established by medical geographers in the imprinting character of southern climates and, secondly, driven by Cross's personal experiences as a chronic arthritic on the Côte d'Azur.

From North to South

Raphaël Dupouy noted that of all the descriptions of Cross by his circle, "the most often is the term 'douceur' [softness, gentleness, delicacy] – the 'doux' Cross – that recurs in the words of his friends, worried about his health."[44] This conception of Cross's intertwined physical state (weak and delicate) and psychological persona (sweet and gentle) remains firmly in place. In 1998, Baligand juxtaposed the strong, "ardent" body of Signac with the weak, "timid" body of Cross: "While the passionate, ardent and eloquent young Signac divided his life between Saint-Tropez and Paris, Cross, of a timid and reserved nature, weakened by a chronic illness, left the south of France only for short stays in Paris on the occasion of the Salons."[45] What significance has Cross's persona as doux had on past and present perceptions of his biography and his neo-impressionist artistic production?

If we accept that a biography is a selective staging of a life, or the narration of progressive milestones, accomplishments, trials and tribulations, then it becomes less an approach to analyzing visual or literary representations than a representation in itself. It is a compilation or assemblage by various contributors of facts, opinions, assumptions, exaggerations, mistakes, and even falsities. One's life and one's biography are therefore two quite different things. I accept that Cross's "true" life is not recoverable. His biography, on the other hand, is a vital source of information that exemplifies deeply-embedded perceptions of the Côte d'Azur as a landscape of mental and physical stimulation, of total bodily liberation for the artist and the invalid.

Cross's biography is inundated with ideas about the climate of the Côte d'Azur initiating a transformation of his health and thoughts. Cross's biographers have repeatedly emphasized his northern French origins, as a man of Douai whose passion for art and true self could not find release until he descended south. Maurice Denis articulated this about Cross as early as 1910:

He was a man of the North who, under a cool appearance, hid with a kind of modesty an ardent heart. He was born in the fog of Flanders, in Douai, where he began to paint; he studied in the cave of Bonvin and grew tired quickly there of... sombre painting; then he settled on the coast of Provence, and it was there that he died between the blue sea and blossoming gardens. All his artistic life took place between this departure from the dark and this arrival to the sun.[46]

Such views of southern climates, particularly those bordering the Mediterranean Sea, as "liberating" occur frequently in contemporaneous literature by writers who were also invalids, though they are part of a much longer tradition of travellers' encounters with the "South."[47] In his early novels as well as in his autobiography, the writer André Gide (1869–1951), a friend of the neo-impressionists,[48] evoked invalid experiences of the Mediterranean that exemplify a widespread perception of the transformative, "imprinting" power of southern climates. In 1895 he began writing Les Nourritures terrestres, which was published in 1897 following his two-year stay convalescing from pulmonary tuberculosis in Biskra, Algeria. Gide and his biographers would describe his recovery as a rebirth akin to a miracle.[49] We find parallels to his own experiences in this pantheistic tale and in the quasi-autobiographical novel of 1902, L'Immoraliste. That novel also takes place in Algeria as well as on the Italian Riviera, in the towns of Sorrento and Ravello. Gide described the descent south in that novel with his protagonist, Michel's voice, writing, "That descent into Italy gave me all the dizzy sensations of a fall.... I felt I was leaving abstraction for life, and though it was winter, I imagined perfumes in every breath…on the threshold of this land of tolerance and promise, all my appetites broke out with sudden vehemence."[50] The transition from northern countries towards the southern coastlines of the French and Italian Rivieras was also expressed in many tourist handbooks as a profound physical and mental experience.[51] The Mediterranean climate, with its drier air, warmer temperature, exotic vegetation, and most especially its light, served as a marker of entry into a new land. Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–94) was even more explicit, writing in an essay entitled, "Ordered South," of 1874:

Moreover, there is still before the invalid the shock of wonder and delight with which he will learn that he has passed the indefinable line that separates South from North. And this is an uncertain moment; for sometimes the consciousness is forced upon him early, on the occasion of some slight association, a colour, a flower, or a scent; and sometimes not until, one fine morning, he wakes up with the southern sunshine peeping through the persiennes, and the southern patois confusedly audible below the windows.[52]

Like Gide, Stevenson was tubercular, and spent the winter of 1873-1874 in Menton. For these writers, the journey south was marked by new sights, feelings, smells of exotic flora, a "softer" air, and increasing luminosity. As invalids, such experiences were felt and perceived to be particularly acute. An invalid diary from the 1860s, written by an anonymous young, tubercular woman sent to Cannes by her physician, posited the healing powers of climate on her ill body as a revitalizing, penetrating, and regenerative transformation. She wrote to her friend, in a poetic entry of December 7, 1864:

Reassure yourself. Perhaps I will not die....Oh! no, it must not be possible to die here, under this exhilarating sun. Life, which overflows with this rich and luxuriant nature, is infectious, and through all the pores it penetrates into you. This air which one breathes, and in that one swims with delight, enters smoothly and softly into the chest; like a miraculous balsam, it tranquilizes the sharpest pains, and causes a delightful freshness to course through the veins.[53]

Similarly in his writings Gide asserted that illness rendered the body more porous to sensations. In Les Nourritures terrestres, Gide's protagonist stated, for instance, that,

At Rome…I went to walk in the gardens every day. I was ill and incapable of thinking; nature just sank into me; thanks to some nervous disorder, my body seemed at times to have no limits; it was prolonged outside myself—or sometimes became porous; I felt myself deliciously melting away, like sugar.[54]

And in another work, he depicted illness as initiating a major life change on his body while in Algeria:

I was lucky to be taken ill over there—very seriously ill, it's true—but my illness did not kill me—on the contrary—it only weakened me for a while, and had the distinct effect of giving me a taste for the rarity of life. It would seem that a weakened organism is more porous, more transparent, tenderer, more perfectly receptive to sensations. In spite of my illness, if not because of it, I was all receptivity and joy.[55]

These statements are crucial for understanding how the invalid was perceived to embody and therapeutically utilize the beneficial climate. In Gide's case, his increased "coenaesthetic preoccupations" (to use Corbin's term) were attributed solely to his illness, through which he perceived tuberculosis as enabling his heightened sensations of his environs. Such perceptions occur too, if only indirectly, in Cross's letters. In an undated letter to Maximilien Luce, Cross once remarked that his arrival at Saint-Clair had immediately influenced him with an overwhelming desire to paint, his own garden providing an absorbing and stimulating motif.[56]Le Jardin Rouge (c. 1906-1907, Private Collection), a composition closed off by a small, compacted space of encroaching foliage, suggests an intimacy of personal space. Simultaneously its seemingly unplanned smattering of units of paint exemplify Cross's aesthetic "liberation" towards a freer, more rapid execution. Denis described the painting's colors as evoking the feeling of summer heat and so intense they threaten to explode on canvas.[57] Cross's friend Verhaeren expressed deep admiration for his southern landscapes, paintings which he felt evoked an overt sensory awareness of the environment: "I love vehemently those of your canvases where the dense, squeezed, even cumbersome vegetation excites all our senses. Vision, smell, touch, taste are simultaneously courted; it reigns there as a pantheistic fire."[58]

Indeed the climate was so powerful in its capacity to alter the body that it could be dangerous. Tourists, and invalids especially, were warned not to indulge to excess under the stimulating influence of southern air.[59] Of weak or doux constitution, the invalid could be too receptive to such a powerful climate, necessitating active self-control.

Sensations, Impressions, Imprints

Letters written by Cross describe his immediate environs with a profound sense of intimacy: "I stroll deliberately and deliciously. I walk often, stopping before my old friends, the pine trees, the rocks, etc. They are numerous and all so rich in serenity as they encroach upon the path!"[60] And in a private notebook while on the Côte d'Azur, he wrote, "The thing that I want to represent…is myself. These trees, these mountains, this sea, it is myself."[61] Cross's own belief in his intimate connection, even integration, with his immediate natural surroundings goes beyond the recognition that his invalid body had successfully completed the process of acclimation to the environment. His words suggest that his visual translation of that environment, namely his landscape paintings, were a kind of self-portrait. In the 1905 preface to Cross's solo exhibition, Verhaeren explained that, following a trip to Italy in 1903, Cross's art had progressed towards aesthetic synthesis and imaginative fantasy, supplementing the direct study and glorification of nature with the glorification of his "inner vision."[62] For Cross, this vision or "personal conception of things"[63] was an active transformative process requiring the artist to submit to one's sensations of nature, yet exercise will-power in order to control them upon visual expression: "What does nature offer us? Disorder, chance, and gaps…. It is necessary to 'organize one's sensations'… for order and fullness…we transform, we transpose, we affirm."[64] Cross described his methodical working process as one of organizing sensations received through a direct study of his immediate environment, a process of transformation, transposition, and affirmation. In doing so, the transformative act involved submitting himself to nature, taking it in, synthesizing its effects, and translating them onto the canvas. He would also describe this process as a game of warring submissions and will-power.[65]

In an undated letter to Cousturier, Cross stated, "I persist to believe that this region is the most beautiful in the world; I have new and exquisite sensations in my garden or when traipsing along the path."[66] Continually receptive to experiencing new sensations, Cross's intimate relationship to that space was fundamental to his approach to painting. If we differentiate his working methods from those of Signac, for example, that intimacy becomes all the more evident. Signac explained his own approach to landscape painting, describing his Le Pin Parasol, "Aux Canoubiers" (1898, Musée de l'Annonciade, Saint-Tropez) in a journal entry of August 9, 1897:

For this landscape I act as I would for a large studio painting, fixing in advance my subject and my composition, and then going out to find in nature the necessary information. I am very happy with this method, and I will no longer use any other. In working here [Saint-Tropez, in his studio] I see what little importance and what little use that working directly after nature has.... I am sure that the man who is really strong can make everything come entirely out of his head.[67]

Cross's territorial intimacy reveals that his very approach to painting operated differently from Signac's, and was premised on an open receptivity to natural sensations. The last sentence of Signac's entry shows he felt that the direct study of nature was a "weak" approach, that the truly "strong," masculine artist had the will-power to resist submission to nature and rely on an active imagination. The so-called doux Cross, on the other hand, saw submission to his received impressions of nature as an important stage in the artistic process. But this was no easy feat for Cross; just like his health, it posed ongoing challenges and required patient study and care. In other words, Cross did not advocate a total submission to nature, "melting" into it as Gide had described and relished during his acute illness; Cross was chronically ill, and this required will-power.

Cross wrote privately of the ongoing difficulty to master self-control in order to concentrate on his work and overcome his physical suffering: "To speak of my works allays my illness. Thought must dominate the body's sufferings. This poor ill and broken body. Conserve a lucid mind to keep self-control."[68] An admirer of the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, Cross's active struggle to overcome suffering and frustration complicates the doux figure depicted by his friends and biographers. For Nietzsche, the pain resulting from invalidism made one more perceptive, liberated in spirit, deepened as a human being, and with greater will-power.[69] In his letters to friends, Cross's working process en plein air reveals the challenges of its aesthetic translation, particularly during 1906 in the studies preparing for paintings such as Le Bois:

During the month of September, I sent for a female model. In a small wood of cork oaks close to home, whether in the sun or in the shadow this nude, in such decor, displayed in front of my eyes harmony of forms and tints entirely original for me. Some poor studies resulted from it. And now that the object is no longer there, I better sense my lack of boldness, my regrettable wisdom and I dream about my sensations which were full of enthusiasm and healthy folly. One shouldn't attempt now to rediscover some spark and reject with all one's might the far too abundant and tyrannical material![70]

These letters and written entries suggest continuous struggle to maintain self-control, balance, and order. Nature here is described as overwhelming, disordered, and tyrannical, his "healthy" sensations of it requiring studious internalization.[71] Yet what Cross meant by "sensations" is difficult to know for certain. In his 1984 book, Cézanne and the End of Impressionism, Richard Shiff noted that the word appears frequently in the letters exchanged between Cézanne, Denis, and Emile Bernard during 1895–1906. Of the word, Shiff explained that,

It is a difficult term in both French and English. "Sensation" has a double meaning since it refers to the perception of something external as well as to internal emotion – seeing and feeling. Considered with regard to its dual reference, the artist's "sensation" becomes analogous to his 'impression'; both experiences (sensation and impression) are simultaneously subjective and objective, interactions that imply the presence of both self and nature.[72]

I argue that the sensation or impression of his environment was perceived by Cross, and has become unconsciously perpetuated by art historians, as particularly acute, not only as an artist but also as an invalid.[73] Artistically, Cross's sensations were the received heightened impressions that marked his intimate experience and knowledge of the Maures environment. Cross's sensations have not been totally subsumed by the process of transposition into the medium of paint and, as Verhaeren and Denis noted, remain as potent visual traces on the canvas. Medically, the invalid's body was conceptualized by geographers and physicians as more delicate and receptive to the environment. The invalids Gide and Stevenson expressed their sensations upon arrival in the South as especially heightened; for Gide, it was "dizzying," and for Stevenson, a "shock of wonder and delight." Like these invalid writers, the sensory overload and pain resulting from chronic arthritis made Cross an artist especially sensitive to the Côte d'Azur and a true aesthete, to himself and to his contemporaries.

Like the standing nude in Nymphes, whose body, covered in green touches of paint, bears the mark of the landscape, so too was Cross's working process stamped by the direct study of and willing submission to nature. In other words, the nudes' integration into the landscape in Cross's Nymphes is a fitting visual metaphor for how the invalid was perceived to take on, receive, or embody the healing properties of southern climates.

Conclusions

Revisiting the narrative of Cross's oeuvre as laid out by Compin in 1964, itself a reiteration of views established first by Denis and Verhaeren, the artist's increasing stylistic and imaginative liberation rehearses an already well-established belief that the invalid's body underwent change due to the imprinting nature of the southern climate. This ongoing narrative of liberation corresponds to the perception that, as an invalid, Cross's body was understood, by himself and his friends, as perpetually doux. That choice of word is significant, for it implies softness, weakness, and delicacy of form and feeling. And as medical geographers and physicians were to assert, the invalid's body was more receptive, open, sensitive, and porous to climate and generally to place. Cross's progressive liberation of style, of color, and of subject matter was, in this context, the inevitable result of his delicate body's open receptiveness to the environment's natural properties. As late as 1998, Baligand described Cross's ultimate artistic development, culminating in the late period, as occurring concurrently with (or even being initiated by) his ultimate bodily suffering:

From 1903, Cross, cruelly afflicted by violent crises of rheumatisms, knew at the same time his most fecund period. After the uncertainties of the previous years, he pushed his researches to the extreme and, abandoning the constraints that he imposed on himself, let his art blossom following his imagination.[74]

Compelling and poignant, Baligand's statement, consciously or not, also positions Cross's disability as a vehicle for artistic escapism, the physical pain a catalyst to imaginative introspection: the more Cross suffers, the more his art benefits. While this perception fuelled Denis's, Verhaeren's, and Cousturier's analyses of Cross's art, and therefore existed within a historically (and, as I have argued, medico-geographically) specific context, today it necessitates recognition as an historical perception. Are there not other, more critical ways of analyzing the relationship between Cross's art and his ill-health?

In one rare instance, a short biography in Philippe Lanthony's Art and Ophthalmology: the Impact of Eye Diseases on Painters (2009), Cross is given a retrospective medical diagnosis to account for the style of his late work. Lanthony declares that Cross's eye troubles, which began in 1901 and culminated in a particularly acute attack lasting for three months in 1905, were due to anterior uveitis (or iritis, an inflammation of the uvea, the middle layer of the eye which includes the iris). Lanthony's sources are Compin, Baligand, and Cousturier, and despite his medical training and focus, he concludes that,

Once the attack of anterior uveitis had resolved, Cross went back to his

painting with a determination that much greater because he sensed

how vulnerable he was. This is proved by the abundance of his production of pictures during this era. The painstaking procedure of Seurat was not at all suitable for an artist who was terrified of going blind and was aware of the urgency of completing his Art work. This was undoubtedly one reason for the development of his style towards a much more open type of painting compared with that of the initiator of Pointillism.[75]

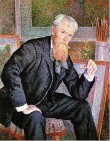

For Lanthony, Cross's liberated facture by 1906 was a simple matter of practicality: quicker, less demanding, and less rigorous than the methodical application of Seurat. The ophthalmologist inserts Luce's portrait of Cross (Portrait of Henri-Edmond Cross, 1898; fig. 6), a work predating his first ocular attack by three years. Lanthony makes no reference to it, leaving his reader to speculate as to its purpose. Are we meant to perform our own retrospective diagnosis from the painting itself? If so, we are sorely frustrated by the fact that Cross displays no obvious symptoms of his disease. He stares at the viewer, clear and steadfast, surrounded by his canvases but not in the physical act of painting, resembling Nicolas Poussin's Self-Portrait of 1650 (Louvre, Paris). It is not an obvious visual declaration of Cross's status as "ill" or as a chronic sufferer. Lanthony's two-page "analysis" of Cross's medical biography is not, to my mind, a productive or critical approach of fusing art and medical histories. To the question, was Cross's art done in spite of or because of his arthritis? I respond, why must it be one or the other? Why the need to attribute stylistic changes in the art to direct physical causes—to the chronic illness itself? If the relationship between them is so direct, so overt, I could equally question the effect Cross's art had on his arthritis, of his aesthetic sensitivity on his physical condition. My point is that their intersection was far more complex, indirect and contentious, and that this one article can only begin to tease this out.

As a starting point, I suggest we, as scholars, position ourselves as empathic towards the artist's self-identification as an invalid and the life choices made because of the daily experiences of chronic illness, and not unique to the case of Cross. I am fully aware that Cross felt quite sincerely that he was a true artist and a suffering invalid, aesthetically and physically receptive to his surroundings, and so did his circle and biographers. I do not wish to suggest this was some deceptive strategy of victimization, on his part or others'. His letters make clear the reality of his chronic pain and his commitment to his career as a modern artist. However, the ongoing frustrations he recorded complicate an easy reading of Cross as a passive invalid and aesthetically "liberated" artist. Rather, the subject that emerges from primary images and texts was a man actively engaged with his art and his health, making informed aesthetic and therapeutic choices throughout his life (i.e., not only during the last five years). This position of strategic empathy has allowed me to engage critically with the literature that has produced a narrative of Cross as the suffering hero who achieves ultimate liberation or freedom, both physical and mental. So too has it allowed me to contextualize this narrative within larger social and medico-geographical beliefs.

When Cross went vers la lumière (towards the light), to the Maures region of the Côte d'Azur, he went there to study its sunlight, take the cure, immerse himself in his environs, and translate his sensations into visual products. In this article I have positioned Cross as an artist-invalid at the center of a network of physicians, tourists, invalids, writers, and artists. Through visual and literary representations and assertions, this intricate network of individuals constructed a shared perception of the Côte d'Azur as aesthetically and therapeutically transformative, and this perception is articulated and conceptualized in Cross's late work like Nymphes and Le Bois (figs. 3, 4). Depicting a literal and metaphorical merging of body and landscape, the paintings are more than merely diagnostic evidence of stylistic liberation, of exemplary late pieces that testify to heightened color and "freer" brushwork; they participate in the very production of that narrative.

I would like to extend my thanks to Natasha Ruiz-Gómez, Keren Hammerschlag, Mary Hunter, Fintan Cullen, Richard Wrigley, and Anthea Callen for their thoughtful and insightful comments on versions of this article. So too do I wish to thank the anonymous readers, who have significantly enriched the piece with challenging and perceptive questions.

[1]"Aussi le touriste et le malade, qui l'un et l'autre cherchent le soleil et la chaude nature, s'arrêtent aujourd'hui frappés d'admiration devant toutes ces merveilles méridionales, l'un pour s'inspirer à cette source de poésie et de grandeur, l'autre pour respirer la santé et la vie au milieu de cette terre promise, sous le ciel toujours bleu. Où trouver en effet une hospitalité à la fois compatible avec l'art et la santé?" J. B. Girard, Cannes et ses environs: Guide historique et pittoresque (Cannes: MM. Girard et Bareste, 1859), 3.

[2] In French medical and tourist literature, sick people or invalids suffering from all manners of chronic and acute disorders and diseases were categorized as malades, but this included convalescents, individus délicats and valétudinaires. For the sake of consistency, I will use "invalid" to designate those of weak or delicate constitution, as well as those diagnosed with either an acute or a chronic disease.

[3] Stéphen Liégeard, La Côte d'Azur (Paris: Maison Quantin, 1887).

[4] For more on the shared aesthetic and therapeutic perceptions of the Côte d'Azur during the nineteenth century, particularly by physicians, see my article, "La Côte d'Azur: The terre privilégié of Invalids and Artists, c.1860-1900," French Cultural Studies 20, no. 4 (November 2009): 383–402.

[5] "Pour certains, le Midi représente un climat accueillant, une forme d'existence agréable dans des paysages qu'il est coutumier de dire paradisiaques et qui, d'ailleurs, le sont; la clémence de l'atmosphère, la beauté des sites, la pureté du ciel ont fait de la Côte d'Azur une sorte de séjour privilégié, de lieu exceptionnel de la nature. Pour d'autres, il a transformé leur vision; la primauté de la lumière et de la forme sur les couleurs a rendu le peintre plus attentif à la structure, à la morphologie des choses." Pierre Cabanne, Le Midi des peintres (Paris: Hachette, 1964), 81–82.

[6] Françoise Cachin has pointed out that many celebrated artists and writers came to the region for their health, see Cachin, ed., Méditerranée: De Courbet à Matisse (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2000), 18.

[7] There has been relatively little written about Cross, and his historiography has been, and continues to be, dominated by French scholars: Isabelle Compin, Françoise Baligand, Claire Maingon, Sylvie Carlier, Monique Nonne, and Raphaël Dupouy. To a lesser extent, Richard Thompson and Margaret Werth have discussed Cross and his work (and in the English language), but as a secondary figure to other artists (Matisse, Signac, etc.). Art historians currently must rely on the only book devoted to Cross's life and oeuvre: Isabelle Compin's monograph, H.E. Cross (Paris: Quatre Chemins – Editart, 1964). Only five hundred copies were ever printed. Two recent catalogues, one from an exhibition in 1998, the other from a small exhibition in 2006, have brought renewed attention to Cross's work: Françoise Baligand and others, Henri-Edmond Cross (1856-1910) (Paris: Somogy Editions d'Art, 1998), and Baligand and others, Henri-Edmond Cross: Etudes et oeuvres sur papier (Le Lavandou: Réseau Lalan, 2006). A new catalogue raisonné is being prepared by Patrick Offenstadt and Claire Maingon, but its release date is still unknown. Additionally, access to Cross's personal letters remains restricted. The majority of them are in the privately-held Signac Archives, though a small collection of his letters can be found in the Special Collections of the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. In this respect Cross is a particularly difficult subject to tackle, and he has been discussed more often in relation to Signac and Théo Van Rysselberghe (1862–1926), his close friends, than independently. As such, he has been positioned as a satellite figure of Neo-Impressionism, living in apparent isolation on the western edge of the Côte d'Azur. A recent exhibition devoted to Cross's work, however, at the Musée Marmottan in Paris (October 20, 2011–February 19, 2012), makes fresh analyses of Cross's oeuvre particularly timely and pertinent.

[8] See entry for 1891 in Isabelle Compin, "Biographie" in Baligand and others, Henri-Edmond Cross (1856-1910),14.

[9] This is a particularly well-established trope for narrating illness and pain, and one that has come to the critical attention of Rebecca Garden in "Disability and Narrative: New Directions for Medicine and the Medical Humanities," Medical Humanities 36, 2 (2010): 70–74.

[10] Christopher Forth's book, The Dreyfus Affair and the Crisis of French Manhood (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004), approached the Affair anew with respect to how both the Dreyfusards and the anti-Dreyfusards communicated their political beliefs, social anxieties, and debates with their opponents through the issue of masculinity. By seeking how the two opposing sides engaged with each other through their masculinity, Forth made evident that politics and social beliefs could be performed through the intimate level of one's own body. He asserted, "This book therefore seeks to put intellectuals back in their bodies" (13). So too do I intend to put Cross back into his body, in order to analyze how he perceived and practiced his life on the Côte d'Azur.

[11] This went back to Hippocrates, who wrote, "In general, you will find the forms and dispositions of mankind to correspond with the nature of the country." Hippocrates, On Airs, Waters, and Places, trans. Francis Adams (Whitefish: Kessinger, 2004), 31.

[12] "La géographie médicale a pour objet la connaissance des modifications imprimées à l'organisme par l'influence des climats, et l'étude des lois qui président à la répartition des maladies sur les diverses parties du globe." J. C. M. Boudin, Essai de géographie médicale (Paris: Germer-Baillière, 1843), 5. The noun "empreinte" and verb "imprimer" occur frequently in nineteenth-century texts of medical geography and climatology in relation to the effects of climate on the physiology, temperament, intellect, and morality of bodies. See for example, H.-C. Lombard, Les climats de montagnes considérés au point de vue médical (Geneva and Paris: Joël Cherbuliez, 1858), xiii; Maurizio M. A. Macario, De l'influence médicatrice du climat de Nice; ou Guide des malades dans cette ville (Paris: Germer-Baillière, 1862), 100; Pierre Foissac, De l'influence des climats sur l'homme et des agents physiques sur le moral (Paris, London, New York and Madrid: Baillière, 1867), 2:90; and H.-J.-A. Sicard, De l'influence climatérique sur la tuberculisation pulmonaire (Montpellier: Boehm & Fils, 1861), quoting on the title page Michel Lévy from his Traité d'hygiène publique et privée (1844-1845): "Chaque population porte l'empreinte des lieux qu'elle habite, elle est ce que la font sa race et le milieu auquel elle s'est adaptée."

[13] "Si nous avons vu les plantes et les animaux porter l'empreinte du climat, enfant de la terre comme les autres êtres, l'homme ne démentira pas cette influence maternelle." François Foderé, Voyage aux Alpes Maritimes (Paris and Strasbourg: F. G. Levrault, 1821), 164.

[14] "La vie de l'homme est, en effet, intimement liée à la nature du milieu qu'il habite; ses moeurs, ses coutumes, ses migrations, son industrie, les moindres conditions de son existence dépendent d'une manière directe de la constitution physique de la surface sur laquelle il s'agite." Charles Lenthéric, La Grèce et l'Orient en Provence (Paris: E. Plon et Cie., 1878), 28.

[15] Foderé remarked of the locals of Hyères, for example: "Ainsi que dans tous les climats où la chaleur favorise la transpiration, les habitans d'Hyères ne sont sujets ni à la goutte, ni au rhumatisme, ni à l'asthme, et les étrangers qui sont attaqués de ces maladies et qui viennent y passer l'hiver, sont presque sûrs, de même que sur le littoral des Alpes maritimes, d'y éprouver un grand soulagement: l'absence des pluies et des brouillards, et l'exercice qu'on peut faire tous les jours, dans cette saison, au milieu d'une belle végétation, rendent certainement ce séjour très-recommandable." Foderé, Voyage, 267–68.

[16] John Murray, AHandbook for Travellers in France (London: John Murray; Paris: Galignani & Co.; Leipzig: Longman, 1847), 437.

[17] In 1864, T. M. Madden explained, "If such be the influence of climate on entire races of man, modifying not only their external form, and the relative importance of the functions of many of their internal organs, but even the development of their intellectual powers…how great then must be its influence on individual men, more especially when these are in a weak and delicate state of health, and therefore infinitely more susceptible of all the good effects of a suitable change of climate." Thomas More Madden, On Change of Climate: A Guide for Travellers in Pursuit of Health (London: T. Cautley Newby, 1864), 30.

[18] This is a topic I have rarely encountered in histories of tourism. For example, Ian Littlewood's Sultry Climates: Travel and Sex since the Grand Tour (London: John Murray, 2001), 1–2, defined tourist motivations during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in chronological, overly reductive terms: those of the connoisseur, the pilgrim, and the rebel. When considered, the invalid is given a marginal role, as in John Pemble's The Mediterranean Passion: Victorians and Edwardians in the South (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), and here only in a British context. Maria Frawley's book is an interesting exception, again in a British context: Invalidism and Identity in Nineteenth-century Britain (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

[19] Alain Corbin, The Lure of the Sea: The Discovery of the Seaside in the Western World, 1750-1840 [1988], trans. Jocelyn Phelps (London: Penguin Books, 1994), 87.

[20] See Woloshyn, French Cultural Studies: 383–402.

[21] See Dr A. Buttura, L'Hiver à Cannes et au Cannet (Paris: Baillière et Fils; Cannes: Robaudy, 1883), 85–86.

[22] As Green argued, in a chapter entitled, "The Problem of Subjectivity": "Generally speaking, the biography carries deeply-ingrained codes and protocols which reinforce highly specific notions of coherent individual 'centredness'. Our trajectory is a different one, building a biographical picture of the interrelationships between private and public, personal identity and social relations." Italics original. Nicholas Green, The Spectacle of Nature: Landscape and Bourgeois Culture in Nineteenth-century France (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1990), 130. On page 133 he clarified that this approach does not follow the traditional biographical method: "It is that we are not dealing conceptually with the kind of monolithic individualism produced and celebrated by the humanist tradition as the gradual emergence of a self-conscious ego, but rather with materially-located personas, shaped by the historical conditions in play."

[23] According to the chronology listed by Compin, "Biographie," 13–15, Cross's joint inflammations occurred first in the 1880s. Specific joint inflammations are listed also, including a particularly bad case of inflammation of the left foot in 1899, requiring ongoing treatment (1903, 1904); eye problems are listed as occurring in 1901 (conjunctivitis of the left eye) and in 1905 (iritis of the left eye), with a reoccurrence in 1907.

[24] See ibid.

[25] "Les souffrances aiguës dans les articulations et les troubles oculaires, qu'il supportait avec courage, lui étaient d'autant plus pénibles qu'ils lui rendaient tout travail impossible et que cette inaction forcée l'abattait moralement. Ainsi aux tourments du corps s'ajoutaient ceux de l'esprit. Mais lorsque sa santé redevenait meilleure, alors, les ressources de sa volonté aidant, il profitait au maximum de ces temps de répit et, comme pour compenser les douloureuses périodes d'anéantissement, laissait s'épanouir sa vitalité longtemps contrainte. Il vivait, du reste, ces moments de paix avec une avidité et une ardeur accrues car il les savait menacés et en pressentait la brièveté." Compin, Cross, 58.

[26] Claire Maignon, "Two Artists Viewed through the Prism of Divisionism: Théo Van Rysselberghe and Henri-Edmond Cross," in Théo Van Rysselberghe (Brussels: Mercatorfonds and the Centre for Fine Arts, 2006), 157.

[27] "Cette particularité d'un développement indéfini de la personnalité de Cross tient à l'essence du caractère de l'homme, obstiné à se découvrir et à s'élargir soi-même à travers les oppressions de toute nature, morales ou matérielles, à travers l'inéluctable maladie même. Rien ne put, que la mort, le contraindre à renoncer aux suprêmes joies que lui procurait un cerveau merveilleux; des oeuvres, toujours plus jeunes, suivaient, comme des revanches, les terribles crises d'athritisme [sic] qui immobilisaient et déformaient ses articulations." Lucie Cousturier, H.-E. Cross (Paris: G. Crès et Cie, 1932), 7.

[28] "Les dernières nouvelles que nous recevons de vous et du bon Théo sont parfaits. Il nous semble aujourd'hui tout naturel que notre amie soit entièrement bien, et nous oublierons facilement qu'il a été si longtemps souffrant et troublé par sa santé. Au fond, le mieux est de penser ainsi....Vous me comprenez. Pour ma part, qui ne fût pas toujours heureuse, j'ai tout oublié, une fois gueri [sic]. Cela n'empêche que la [sic] fait de la guerison [sic] de Théo nous a profondément réjoui." Letter from Cross to Maria van Rysselberghe, November12, 190[?], Théo Van Rysselberghe Archives, Correspondence, ca.1889–1926, Series I-V (870355), Special Collections, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[29] Cross apparently experienced arthritis from a young age, though his exact type of arthritis is not known, nor indeed were categories of arthritisme distinct during his own lifetime. As Dr. Burney Yeo noted, "So much difference of opinion exists as to the precise pathological nature, affinities, and appropriate nomenclature of certain chronic, painful conditions of joints, that it is somewhat difficult, in approaching the subject from the therapeutic point of view, to make it perfectly clear what are the morbid states, or better, what are the particular cases, we are contemplating." He specified that these were even less clear in France: "Many French authors are dominated by a general conception of the existence of 'arthritism,' that is, an inherited diathesis or constitution which determines a tendency to arthritic affections generally, and to which they refer diseases differing so widely as acute gout and arthritis deformans, which, however, they trace to a common origin or diathesis, and between which they see a pathological affinity." Yeo was equally vague about its cause, though did mention that, "The most common existing cause is exposure to cold and wet." Burney Yeo, A Manual of Medical Treatment or Clinical Therapeutics (London, Paris and Melbourne: Cassell and Company Limited, 1893), 473–75.

[30] A reference to electrotherapeutic treatment can be found in a letter from Cross to Luce (undated, likely c. June 1904), Cousturier Archives (2001.M.15), Special Collections, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. He refers also to receiving massage from a relative, in an undated letter from Cross to Mme Van Rysselberghe, Théo Van Rysselberghe Archives, Correspondence, ca.1889–1926, Series I-V (870355), Special Collections, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[31] Cross explains this in a letter to Angrand, October 21, 1906, quoted in Compin, Cross, 267–68.

[32] Compin divides Cross's oeuvre into periods: 1856–84 (youth); 1884–91 (the birth of the Indépendants, of which he was a founding member, to his pre-Neo-Impressionist work); 1891–95 (his move to the Maures and his first Neo-Impressionist work); 1895–1903 (the beginning of new liberties to his technique); and 1903–10 (his late period, from his first trip to Italy to his death). Compin, Cross, 367.

[33] "Les teintes que Cross dispose ainsi sont pures mais douces, car fortement mélangées de blanc. C'est que, à cette époque, Cross cherche à exprimer la vérité lumineuse par la décoloration, ayant observé que la vive lumière absorbe les couleurs." Ibid., 38.

[34] Maurice Denis wrote, in the preface for Cross's second solo exhibition catalogue, "J'ai découvert, disait Cézanne, que le soleil est une chose qu'on ne peut pas reproduire, mais qu'on peut représenter. Cross a pris, comme les anciens maîtres, le parti de représenter le soleil non pas par la décoloration, mais par l'exaltation des teintes et la franchise des oppositions," in Exposition H.-E. Cross (Paris: MM. Bernheim Jeune & Cie, 1907), unpaginated.

[35] "Fortifié par la sévère discipline néo-impressionniste, Cross cherchait désormais à la dépasser. Avec elle, comme avec la représentation littérale de la nature, il allait prendre plus de libertés et c'est ainsi que, de 1895 à 1903, se fit son évolution vers un art plus personnel." Compin, Cross, 42.

[36] "une exécution à la fois plus libre et plus rapide." Ibid., 44.

[37] Ibid., 63.

[38] "composait, et son imagination libérée appelait les nymphes, les faunes et les dryades pour emplir de formes sculpturales des paysages élyséens." Maurice Denis, "Henri-Edmond Cross (Préface à l'exposition posthume d'Henri-Edmond Cross, Bernheim, Oct–Nov 1910)," in Théories, 1890-1910: Du Symbolisme et de Gauguin vers un nouvel ordre classique (Paris: Bibliothèque de L'Occident, 1912), 159. The Symbolist connections to this series of fauns and nymphs is unfortunately beyond the scope of this paper, but certainly it should be noted that works such as Faune (1905-1906, location unknown) were directly inspired by Stéphane Mallarmé's L'Après-midi d'un faune (1876). I extend my thanks to the anonymous reader who pointed this out, as Cross's Symbolist affiliations remain an under-developed topic.

[39] "où l'être humain, avec sa chair humaine, ne semble exister, lui-même, que comme une plante chargée de fruits, soulignent déjà cette personnelle conception des choses." Emile Verhaeren, letter-preface to Exposition Henri Edmond Cross (Paris: Galerie E. Druet, 1905), 7. I would like to thank an anonymous reader for noting that Octave Mirbeau similarly described figures en plein air in works by Pissarro as "plantes humaines," see "Camille Pissarro," Le Figaro, February 1, 1892. Perhaps most well known is Michelet's pronouncement of humans as flowers in La Femme (1860). He wrote, "The human flower, more than all others, craves for the sun," in Jules Michelet, Woman, trans. by J. W. Palmer (New York and Paris: Carleton, 1866), 53.

[40] "les figures s'intègrent au paysage, car formes végétales et formes humaines, fondues en de mêmes arabesques, participent également au rythme général." Isabelle Compin, "Henri Edmond Cross, 1856-1910," in Jean Sutter, ed., Les néo impressionnistes (Neuchâtel: Editions Ides et Calendes, 1970), 74.

[41] "Les…personnages, sous l'éclairage intense, s'intègrent au paysage et participent à cette communion avec une nature généreuse et sensuelle." Baligand, "Cross, son oeuvre," in Baligand and others, Henri-Edmond Cross (1856-1910), 48.

[42] Baligand continues to assert that Cross's late work "opened" or gave way to a fauve style. See her "Henri-Edmond Cross, 1904-1907: Entre néo-impressionnisme et fauvisme," in Baligand and others, Henri-Edmond Cross: Etudes, 88–103, and her recent paper, "Les années 1891-1900: Cross, Signac et Van Rysselberghe, la couleur libérée," presented at the conference, New Directions in Neo-Impressionism, at Richmond, the American International University in London, on November 20, 2010.

[43] So too have Renoir's late works been discussed as freer in execution and his palette "hotter," with an increasing use of reds. See Nevile Wallis, "Renoir: A World of Sensuous Beauty," The Connoisseur 132, January 1954, 179. Barbara Ehrlich White has explained that "in the last twenty-five years of his life…[h]e now used twice as many reds as he did in the late 1870s." White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1984), 221. John House, discussing Woman at her Toilet of c. 1918, has written that "the colour here is very rich, dominated by the reds and oranges which Renoir used to evoke the idea of the South of France as a warm health-giving region." House, ed., Renoir, Master Impressionist (Sydney: Art Exhibitions Australia Limited, 1994), 140.

[44] "le plus souvent, c'est le terme de douceur – 'le doux Cross' – qui revient dans les mots de ses amis, inquiets de sa santé." Raphaël Dupouy, "Le doux Cross: Quelques précisions sur un artiste profond et attachant," in Baligand and others, Henri-Edmond Cross: Etudes, 24.

[45] "Alors que le jeune Signac passionné, fougueux et éloquent partage son existence entre Saint-Tropez et Paris, Cross d'une nature timide et réservée, affaibli par une maladie chronique, ne quitte le sud de la France que pour de brefs séjours à Paris à l'occasion des Salons." Françoise Baligand, "Seurat, Signac Cross et le néo-impressionnisme," in Baligand and others, Henri-Edmond Cross (1856-1910), 20.

[46] "C'était un homme du Nord qui, sous des apparences froides, cachait avec une sorte de pudeur un coeur ardent. Il naît dans le brouillard de Flandre, à Douai, où il commence de peindre; il passe dans la cave de Bonvin et s'y lasse vite…de la peinture sombre; puis il s'installe sur la côte de Provence, et c'est là qu'il meurt entre la mer bleue et les jardins fleuris. Toute sa vie d'artiste tient entre ce départ dans le noir et cette arrivée dans le soleil." Denis, "Henri-Edmond Cross" in Théories, 156.

[47] For works dealing explicitly with this tradition of northern tourist and artist encounters with the south (or "South," a construct of imagined geography not unlike the "Orient"), see Robert Aldrich, The Seduction of the Mediterranean: Writing, Art and Homosexual Fantasy (London and New York: Routledge, 1995); Littlewood, Sultry Climates; Roger Bray, Flight to the Sun: The Story of the Holiday Revolution (London: Continuum, 2001); and Vojtĕch Jirat-Wasiutyński, ed., Modern Art and the Idea of the Mediterranean (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007).

[48] Van Rysselberghe and Gide had been friends since 1899, through Emile Verhaeren. See Peter Schnyder, "André Gide and Théo Van Rysselberghe: A Glimpse at an Unpublished Correspondence," in Théo Van Rysselberghe, 171–83. Gide seems to have become personally acquainted with Cross around 1902, no doubt through the intervention of their mutual friends, Verhaeren and Van Rysselberghe. Gide and Cross also shared a friend in the person of Denis. Denis had illustrated Gide's Le Voyage d'Urien in 1893, and they spent time together in Rome, in 1898 and in 1904. See Maurice Denis, Du symbolisme au classicisme: Théories, ed. Olivier Revault d'Allonnes (Paris: Hermann, 1964), 27, and Denis, Journals. Volume I: 1884-1904 (Paris: La Colombe, 1957), 201.

[49] Carlo Bronne has explained, "Gide est à Biskra…[et] il écrit les Nourritures terrestres, hymne panthéiste à tout ce qui est disponible parce que, durant les deux ans de son séjour algérien, il a eu la révélation de la joie et de sa propre nature. Après s'être cru tuberculeux, il savoure la convalescence qui pour lui est mieux qu'une résurrection; c'est une naissance." Carlo Bronne, Rilke, Gide et Verhaeren: Correspondance inédite (n.p.: Messein, 1955), 48.

[50] André Gide, The Immoralist, trans. Dorothy Bussy (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1981), 139.

[51] William Scott wrote in 1907, "Those who are 'coming South' for the first time, if they have any real sensitiveness or imagination, must surely feel they are entering some fair Eden; passing from a desert to a Land of Promise... [exchanging] the dark lowering clouds, fierce tempests, howling winds, and dense chilly fogs of the North for the blue skies, soft air, bright sunshine, [and] the breath of flowers." William Scott, The Riviera: Painted & Described (London: A. & C. Black, 1907), 4–5.

[52] Robert Louis Stevenson, "Ordered South" [1874], Virginibus Puerisque and Other Papers by Robert Louis Stevenson (London: Chatto and Windus, 1921), 87.

[53] "Rassure-toi. Je ne mourrai peut-être pas.… Oh! non, on ne doit pouvoir mourir ici, sous ce soleil vivifiant. La vie, qui déborde de cette riche et luxuriante nature, est contagieuse, et par tous les pores elle vous pénètre. Cet air que l'on respire, et dans lequel on se baigne avec délices, arrive onctueux et doux à la poitrine; comme un baume miraculeux, il calme les douleurs les plus vives, et fait courir dans les veines une délicieuse fraîcheur." A. Macé, ed., Cannes: Lettres d'une jeune femme (Cannes: Librairie et Papeterie de Fortuné Roubaudi, 1865), 15.

[54] André Gide, Les Nourritures terrestres, trans. Dorothy Bussy (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970), 48.

[55] André Gide, Le Renoncement au voyage (Oeuvres complètes, [1933], 4:301)quoted in Jean Delay, The Youth of André Gide, trans. June Guicharnaud (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1963), 344.

[56] Undated letter from Cross to Luce, Edmond Cousturier Archives, Miscellaneous papers, ca.1890–1908 (2001.M.15), Special Collections, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[57] Maurice Denis, in Exposition H.-E. Cross, cited in Robert L. Herbert, Neo-Impressionism (New York: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1968), 50.

[58] "J'aime violemment celles de vos toiles où les végétations touffues, serrées, encombrantes même, exaltent tous nos sens. La vue, l'odorat, le toucher, le goût sont à la fois sollicités; il y règne comme une ardeur panthéiste." Verhaeren, Exposition Henri Edmond Cross, 6.

[59] An anonymous guide to Cannes of 1878 warned readers that, "The stimulating character of the climate necessitates caution in diet. Visitors from England should take care to drink less wine and spirits than they are accustomed to; for that which in England is a moderate and harmless quantity is hurtful and excessive here." F. M. S., Visitor's Guide to Cannes and its Vicinity (London: Edward Stanford; Paris: Galignani & Co.; Cannes: John Taylor and Riddett, 1878), 11. Cross appears to have been warned of this danger of over-stimulation to his delicate body as well. In a letter from around 1903-1904, he wrote to Luce from Saint-Clair that, "Des petits vents respirables qui soufflent sur la sueur et la glacent. C'est dangereuse, mais de sensation exquise. La plupart des bonnes choses sont ainsi; par exemple l'alcool que j'adore et dont je suis obligé de me priver. C'est idiot!" Cross describes the exquisite sensation of a cool breeze in the outdoor heat, but for an invalid any dramatic changes to temperature were considered to be dangerous. Letter from Cross to Luce (summer, c. 1903-1904, after Venice), Edmond Cousturier Archives (2001.M.15), Special Collections, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[60] "Je flane [sic] volontairement et délicieusement. Je marche beaucoup, m'arrêtant quelquefois devant les vieux amis les pins, les roches etc. Ils sont nombreux, et tous si riches en sérenité [sic] qu'ils déversent sur la route!" Letter from Cross to Mme Van Rysselberghe, September 27, c. 1903-1904, Van Rysselberghe Archives (870355), Special Collections, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[61] "La chose que je veux représenter…c'est moi-même. Ces arbres, ces montagnes, cette mer, c'est moi-même." John Rewald, ed., Henri-Edmond Cross: Carnet de dessins (Paris: Berggruen and Cie, 1959), 1.

[62] "Le grand et pieux respect que vous avec montré pour la nature, la franche et intransigeante sincérité dont vous fîtes preuve en l'étudiant et en l'aimant, vous les voulez diriger à cette heure vers un autre objet. Et vous rêvez, comme vous me l'écriviez, de faire de votre art, non plus seulement la 'glorification de la Nature,' mais la 'glorification même d'unevision intérieur.'" Verhaeren in Exposition Henri Edmond Cross, 3. In other words, having descended further south, into Italy, Cross's aesthetic sensibilities and imagination had become even further refined.

[63] "où l'être humain, avec sa chair humaine, ne semble exister, lui-même, que comme une plante chargée de fruits, soulignent déjà cette personnelle conception des choses." Verhaeren in Exposition Henri Edmond Cross,7.

[64] "Que nous offre la nature? le désordre, le hasard, des trous....C'est ici qu'il faut 'organiser ses sensations'… de l'ordre et de la plénitude.… Nous transformons, nous transposons, nous affirmons." From a private notebook, cited in Félix Fénéon, "Inédits d'Henri-Edmond Cross," Bulletin de la vie artistique, June 1, 1922, 256–57.

[65] He wrote, "J'ai travaillé ces temps derniers, directement sur nature. Une toile de mon jardin avec des petits figures; et un ou deux autres paysages. On goute dans le travail direct toute la partie sensuelle et puis, c'est j'ai ce jeu de soumissions et de volonté alternées!" Letter from Cross to Luce (undated, but c. June 1904), Edmond Cousturier Archives (2001.M.15), Special Collections, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[66] "Je persiste à croire que ce pays est le plus beau du monde; j'y ai des sensations neuves et exquises dans mon jardin ou sur la route quand je puis m'y trainer [sic]." Undated letter from Cross to Lucie Cousturier, Edmond Cousturier Archives (2001.M.15), Special Collections, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

[67] Paul Signac (Journal Entry, August 9, 1897) cited in Herbert, Neo-Impressionism, 143.

[68] "Parler de mes travaux endort mon mal. La pensée doit dominer les souffrances du corps. Ce pauvre corps malade et brisé. Conserver l'esprit lucide pour garder le contrôle de soi." Quoted in Dupouy, "Le doux Cross," 24.

[69] As Nietzsche proclaimed, "It is great pain only which is the ultimate emancipator of the spirit…It is great pain only, the long slow pain which takes time, by which we are burned as it were with green wood, that compels us philosophers to descend into our ultimate depths, and divest ourselves of all trust, all good-nature, veiling, gentleness, and averageness, wherein we have perhaps formerly installed our humanity. I doubt whether such pain 'improves' us; but I know that it deepens us. Be it that we learn to confront it with our pride, our scorn, our strength of will…one emerges from such long, dangerous exercises in self-mastery as another being, with several additional notes of interrogation, and above all, with the will to question more than ever, more profoundly, more strictly, more sternly, more wickedly, more quietly than has ever been questioned hitherto." Italics original. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science (Die Fröhliche Wissenschaft) [1882], preface to 1887 edition, trans. by Thomas Common (Mineola: Dover Publications, 2006), x.