The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Alexandre Cabanel: La Tradition du Beau

Musée Fabre, Montpellier

July 10, 2010–January 2, 2011

Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne

February 4, 2011–May 15, 2011

Alexandre Cabanel: La Tradition du Beau, organized by the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, offers the first retrospective exhibition of Alexandre Cabanel since his death in 1889. The exhibition presents a comprehensive examination of Cabanel's rise to the heights of acclaim during the second half of the nineteenth century, and places his work both among that of his peers and in a well-considered historical context. The curatorial team, headed by the Musée Fabre's director Michel Hilaire and curator Sylain Amic, undertook extensive research and has brought together works from around the world, as well as extensive documentary material that makes the exhibition a rich and rewarding experience.

The exhibition presents a chronological approach to Cabanel's work, and offers visitors the opportunity to consider his development as an artist and to contemplate his challenges in the face of institutional and critical responses as well as his increasing success with private patrons. Two early self-portraits, from 1836 and 1840, greet the visitor at the entrance to the exhibition and reveal Cabanel's impressive talent as early as thirteen years of age. Born in Montpellier in 1823, Cabanel studied at the municipal drawing school that was then housed in the same building as the Musée Fabre. In 1840, with the support of a scholarship from his hometown, Cabanel moved to Paris and entered the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

The first room of the exhibition, Towards the Prix de Rome, allows visitors to compare the works Cabanel submitted for the coveted Rome prize with those of his competitors, Félix Barrias and Léon Benouville, behind whom he ranked 1844 and 1845 respectively. Examples by each artist on the subject of Cincinnatus Receiving the Ambassadors from Senate (1844) not only suggest that Cabanel had mastered the prerequisite frieze-like composition and rhetorical gestures like the others, but also illustrate his unusual use of intense color, particularly the vibrant orange drapery of one of the principal figures, which alienated his critics (fig. 1). In 1845, however, Cabanel received a scholarship for Rome even though his Jesus in the Praetorium ranked second to that of François-Léon Benouville. In an unusual turn of events, he was granted this position when a prize was not awarded in the category of musical composition; this is just one example of the good fortune that Cabanel enjoyed throughout his career. Cabanel's copies after Giorgione's Concert and Diego Velasquez's The Infanta complete the presentation of his early artistic training.

This theme develops in the second room, The Rome Years, which focuses on 1846 to 1851 when Cabanel was at the Villa Medici. The installation of portraits and paintings successfully evokes his circle, which included previous rivals Benouville and Barrias, along with architect Alfred Nicolas Norman and printmaker Louis-Félix Chabaud (fig. 2). During his years in Rome, Cabanel also enjoyed the patronage of Alfred Bruyas, another native of Montpellier. The exhibition brings together the trilogy of paintings commissioned by Bruyas: La Chiaruccia, Man Contemplating, Young Roman Monk, and Albayde (fig. 3). From the picturesque depiction of a Roman woman through the usual presentation of a monk before the ancient city to the seductive beauty of Albayde, a character from Victor Hugo's Orientales (1829), the trilogy shows how Cabanel played with body and facial positioning as well as settings to fulfill the refined taste of his new patron. However, the origin of the trilogy's conception is not clear. Bruyas was already a significant collector when he visited Cabanel in Rome in 1846 and 1848, as Auguste Glaize's Interior of the Bruyas Cabinet (1848) reveals, and it is this effort to contextualize both Bruyas as a collector and Cabanel among his fellow pensioners at the Villa Medici, that makes the presentation of these early works particularly meaningful. (It should be noted that this material will not travel to Cologne, where only works by Cabanel will be exhibited). A darkened anteroom with prints, drawings, and photographs (daguerreotypes and later paper negatives) of the Villa Medici and four small-scale studies of Roman subjects by Ernest Hébert complete the historical contextualization of the privileged setting in which Cabanel was immersed, with, in his words, only art as his mistress.

The third room, The Work from Rome, captures the increasing scale and confidence of the annual compositions Cabanel was expected to send to Paris. Here we also witness his struggles. Neither the educators at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts nor the art critics were enthusiastic about his bold handling of subjects such as Orestes (1846) and The Fallen Angel (1847; inspired by poet, John Milton) and his attempts at the necessary mastery of the male nude (figs. 4 and 5). In 1848 Cabanel finally achieved some level of appreciation from the critics with Saint John the Baptist that was inspired by Guido Reni and Raphael (fig. 6). Within the regimented structure of the annual assignments at the Villa Medici, Cabanel was require to send a painted esquisse with at least twelve figures during his fourth year. Saint Paul among the Faithful of Caesarea (1849) was perceived as a failure due to the confusion of his composition, but it did signal Cabanel's interest in both complex scenes and the writings of saints (fig. 7). The principal work of his last year, The Death of Moses (1850) finally brought Cabanel acclaim when it was exhibited at the Salon of 1852, and it launched his career in Paris (fig. 8). When he returned from Italy, Cabanel was among the most sought after Rome-trained artists of his generation. In the Moses composition, Cabanel resolved the challenge of twelve figures, many of them life size; here, the two principal figures, God and Moses, define a diagonal composition while secondary figures flanking Moses create a stabilizing triangle, and a tertiary group fades into God's billowing drapery. The careful placement of Gustave Le Gray's photograph of the Grand Salon from 1852 across the room from The Death of Moses allows viewers to take in both works in one glance, and to reconstruct fully its original setting (fig. 9). This is just one such example of the painstaking care with which the exhibition has been installed.

The same can be said for the juxtaposition of the painted sketch and final composition of Christian Martyr (1855), displayed on opposing walls of the room dedicated to Debuts at the Salon (fig. 10). Such thoughtful placement of related pieces allows for a full appreciation of both works and, therefore, a greater understanding of Cabanel's success with this weighty composition at the Universal Exposition of 1855. During the early 1850s, Cabanel exercised his right to exhibit works without submitting them first to the jury, and he also enjoyed the support of a diverse group of patrons that included the French state (Saint John the Baptist, 1850), financier Isaac Pereire (Aglae and Boniface, ca.1857), and the ever supportive Bruyas (Valléda, 1852). The context for art patronage in the mid-1850s seems much less polarized than is traditionally thought of Second Empire Paris when one considers Bruyas's interest in the work of Octave Tassaert, Cabanel, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Eugène Delacroix, and Gustave Courbet, among others, before his retreat to Montpellier later in the 1850s.

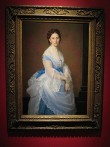

The next room dedicated more broadly to The Painter of the Second Empire serves as a highlight and almost an annex to the exhibition, as it brings together Cabanel's recently restored Portrait of Napoléon III (1865) and two related sketches (The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, and Musée Fesch, Ajaccio, Corsica), as well as Ruth Returning from the Fields, both of which were hung in Empress Eugénie's study at the Tuileries palace (fig. 11). The broader court context is also evoked with Hippolyte Flandrin's Portrait of Napoléon III (1862), Edouard Louis Dubufe's Portrait of Empress Eugénie (1853) and Cabanel's Portrait of Mme Carette (1868) an appealingly frank representation of a woman who was lectrice in the empress' household, then demoiselle d'honneur, and finally, dame du palais as of 1866, and whose portrayal suggests Cabanel's later success as a society portraitist (figs. 12 and 13). It could be argued that Cabanel's Portrait of Napoléon III suffers by comparison with the psychological complexity of Flandrin's portrait. However, what is more significant is Cabanel's unusual treatment of this official portrait as a representation of the emperor in civilian dress despite the ermine-lined cloak and imperial accessories surrounding him. It is not only the clothing, but also the frankness and lack of idealization in Napoléon III's expression that makes the portrait strikingly modern for its time. Exactly the opposite of Flandrin, Cabanel's portrait enjoyed a positive reception from the imperial court, but was received negatively by the art critics.

The exhibition then offers another significant achievement when it reconstitutes the 'Salon de Venus,' as the Salon of 1863 was known. In The Triumph of Venus, a room dedicated to four large paintings, the juxtaposition of canvases by Cabanel and Eugène Emmanuel Amaury-Duval, both entitled The Birth of Venus (1863, 1862) and Paul Baudry's The Pearl and the Wave (1862) allows for a full appreciation of the representations of the female nude that captivated the French public the same year as Manet's Luncheon on the Grass did at the Salon des Refusés (figs. 14 and 15). Amaury-Duval's work now appears quite derivative of J.-A.-D. Ingres and it is the pairing of nudes by Cabanel and Baudry, bought for the private collections of Napoléon III and Eugénie respectively, that leaves a lasting impression. The alternating poses, and variations in coy expressions place Cabanel's Venus in context. Cabanel's canvas does not become less representative of its historic moment, but Baudry's composition seems more innovative for its markedly different handling of energetic waves, anecdotal details of shells and the roughed-in plants in the foreground. The exhibition label states that Cabanel was crowned the victor, but Théophile Gautier's nearly orgasmic reading of Baudry's composition, published on the front page of Le Moniteur universel, (June 13, 1863) suggests otherwise. Cabanel's earlier achievement, Nymph Captured by a Faun (1860) ironically offers greater erotic allure on the wall opposite the Birth of Venus, although the former has developed an unfortunate degree of craquelure in the intervening years (fig. 16).

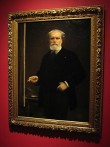

The tone of the exhibition changes significantly in the rooms dedicated to The Master of the Portrait where Cabanel emerges as the successful portraitist of both European aristocracy and prominent American patrons. In spite of these achievements as a portraitist, Cabanel's handling of paint often seems stiff and the results can be prosaic. Of greater interest in this context are the numerous preparatory drawings and the remarkably well-preserved dress of Mrs. Louise Van Loon-Borski, which is placed next to Cabanel's portrait of her in the same dress, (1887) (fig. 17). Cabanel's handling of paint here appears surprisingly lacking in depth and texture although his sincere presentation of the sitter's face offers more appeal. The Portrait of Mrs. Louise Van Loon-Borski has not been restored, and thus it may suffer by comparison with other works such as the Portrait of Baroness Paul von Derwies, (1871) (fig. 18). A visit to Cabanel's studio and ensuing commissions by numerous American art collectors, such as Mrs. Collis P. Huntington, round out the presentation of Cabanel's popularity in the Gilded Age. In a rare shift from his usual focus on contemporary dress, Cabanel's portrait of Mrs Pinchot and her Children in Florentine Costume from the 15th Century, (1872) shows how he could achieve much greater success with portraits more closely attuned to a patron's personal interests.

Cabanel's works from the 1870s and 1880s, many of which are grouped together under the title The Art of Drama, reveal the artist's debt to the Orientalist pursuits of the previous decades as well as emerging symbolist practices. Alongside his success as a portraitist, Cabanel sought to maintain his status as a history painter and is at the height of his talents in this realm with the opulent rendering of The Death of Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta, (1870) and the sumptuously detailed Phaedra, (1880) (figs. 19 and 20). The most striking composition in this category, however, is Cleopatra Testing Poisons on Condemned Prisoners, (1887) which was commissioned for the Royal Academy in Antwerp (fig. 21). The success of Cabanel's narrative drama is enhanced by the juxtaposition of the canvas next to a film screen playing a cinematic rendition of the well-exploited story from Plutarch (Life of Anthony, chapter LXXX). As Cabanel's last large composition, this painting shows his enduring ability to create sensuously evocative, and yet technically restrained, historical detail.

There is an unfortunate disconnect between the previously discussed principal rooms of the exhibition and the spaces on the second floor of the gallery that are dedicated to Cabanel Designer and Decorator. Here, the curators have done their best to evoke Cabanel's large-scale public commissions including The Life of Saint Louis, for the Panthéon which is reconstructed with sketches and studies for the cycle that met with great acclaim during the Universal Exposition of 1878 (fig. 22). The Paradise Lost painting, commissioned by the architect Leo von Klenze for the Munich-based art academy of Bavarian King Maximilian II, also is reconstituted through preparatory drawings and painted sketches (fig. 23). It was exhibited in Paris in 1867 before it was shipped to Munich, where it was destroyed in 1945. Despite the achievements of notable painted studies, such as the moody rendering of Adam, (1863-67), the room dedicated to this lost painting received little attention from visitors, but is still a successful reconstruction of Cabanel's most important commission for an institution outside of France. If Cabanel's sometimes mechanical painting practice appeals less to certain viewers, the drawings will not disappoint. A study for an Angel (1863-67, pierre noire with white highlights on chamois paper) for Paradise Lost epitomizes Cabanel's talents as a draughtsman (fig. 24). These achievements could have been better presented if integrated to a greater degree into the better-attended rooms on the main floor of the exhibition. Particularly the commissions, such as the voussoirs for the Salon des Caryatides at the Hôtel de Ville would have been presented to greater advantage if placed within the chronological organization of the exhibition. Certainly all of this material is well integrated into the exhibition catalogue that will remain an important resource for scholars of nineteenth-century art.[1]

The catalogue is also much more successful than the exhibition in the presentation of Cabanel's paintings for the hôtels particuliers of Constant Say (ca. 1861) and the Pereire brothers, Isaac and Émile (1859, 1864). The attempt at offering a virtual tour of these spaces in the exhibition falls short as, unfortunately, does the display of the large-scale drawings. Despite the considerable effort to present Cabanel's decorations for these two grand Parisian settings, it remains difficult to evoke monumental nineteenth-century wall painting out of context. The exhibition organizers should be praised for their efforts, and for the comprehensive coverage of the material in the catalogue. Just as Cabanel presents himself smoking and posed casually before an easel in his Self-Portrait from 1885, this important exhibition demonstrates how aspects of Cabanel's work position him as a central figure within debates around painting and modernity in the nineteenth-century (fig. 25).

Alison McQueen

McMaster University

ajmcq[at]mcmaster.ca

[1] Michel Hilaire and Sylvain Amic, Alexandre Cabanel 1823–1889, La Tradition du Beau (Paris: Somogy, 2010).