The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

Échappées nordiques: Scandinavian and Finnish Artists in France, 1870-1914 Exhibition catalogue: (fig. 1) |

||||||||||

|

|

The exhibition of works by nineteenth-century Scandinavian and Finnish artists at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille narrates a subtle account of aesthetic influence and innovation (fig. 2). After the end of the Franco-Prussian war, artists from across Europe travelled to France in order to broaden their artistic training, to establish dialogues with leading academic and avant-garde painters of the period, and to exhibit at two of Europe’s most highly profiled exhibition spaces, the Paris Salon and the Exposition universelle. However, this exhibition illustrates not just the broad attraction and influence of French schools of painting, education and exhibition practice during the late nineteenth century, but also demonstrates how Nordic artists experimented with French styles of painting and gradually adapted those styles to suit their own aesthetic and intellectual aims. |

||||||||||

|

In addition to the intrinsic interest of the works on display and the artistic exchanges they illustrate between Northern Europe and France, the exhibition provides insight into an important aspect of nineteenth-century French museology. With one exception, the works in the exhibition are on loan from permanent collections of museums throughout France. By bringing these works together, the exhibition testifies to French interest in Nordic painting during the late nineteenth century and, more importantly, illustrates the aesthetic preferences of officials who administered the fine arts policies of the Third Republic. This particular feature of the exhibition also distinguishes it from two earlier exhibitions of Nordic painting in France, namely, The Painters’ Europe at the Musée d’Orsay in 1993 and Northern Lights at the Petit Palais in 1987. |

|||||||||||

|

|

Rural Landscape |

||||||||||

|

Exceptions to the naturalism characteristic of the introductory works are two smaller-scale landscapes by Thaulow from the 1890s. As one of the few artists included in the exhibition who had direct contact with members of the Parisian avant-garde such as Auguste Rodin, Claude Monet and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Thaulow’s more intimate landscapes experiment with a palette and technique familiar from works by members of the Barbizon school and from landscape paintings by Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley. |

|||||||||||

|

Tracing stylistic influences of artists on one another is not an easy task. However, given that the theme of artistic influence is one of the major features of this exhibition, it is a subject that needed to be addressed in a more detailed fashion. The catalogue essays cite various friendships that developed between Nordic artists and their French contemporaries and highlight the opportunities that arose for Finnish and Scandinavian artists to train with French painters and to view the latters’ works in the exhibition spaces of Paris. However, the full diversity and detail of the resulting pictorial and stylistic influences are not brought out in the exhibition or in the essays themselves. The theme of influence is, therefore, left at a tantalizing level of generality that could have been remedied by a fuller discussion of French academic painting of the period, the debate in France about the social and aesthetic potential of naturalism in art, and critical discussions that arose in the reception of French landscape and portraiture. |

|||||||||||

|

|

The second principal room of the exhibition focuses on portraiture, but retains the sense of grandeur established by the introductory works. The center of focus is the imposing portrait of Louis Pasteur painted by the celebrated Finnish portraitist, Albert Edelfelt, in 1885 (fig. 4). Also included is Edelfelt’s portrait of his friend and academic painter, Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, with whom Edelfelt became associated during his studies in the studio of Jean-Léon Gerôme. The grouping of works in this room illustrates not only Edelfelt’s approach to portraiture as a means of capturing spontaneous moments that highlight individual character, but also the close ties between Edelfelt and the Pasteur family that developed during the 1880s. The exhibition includes impressive oil portraits of Pasteur’s close family relations and of his colleague, Émile Roux as well as more intimate pastel portraits of Pasteur’s daughter and granddaughter. Displayed in a small side room, these pastels are exhibited alongside small portraits by Swedish artists Anders Zorn and Allan Österlind the ease and intimacy of which are enhanced by their execution in pen and ink, watercolour and pencil. |

||||||||||

|

Edelfelt’s works comprise most of the Finnish component of the exhibition. As hinted at in Riitta Ojanperä’s catalogue essay, this results in a highly selective impression of Finnish art at the end of the nineteenth century and, in particular, overlooks the important contribution to Finnish cultural life made by female artists who also undertook their training in Paris during the 1880s. The eclecticism of the selection is, however, inevitable given that the works exhibited are those bought by the French state during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, the exhibition does not purport to be an overview of late nineteenth-century Scandinavian and Finnish painting in its entirety, and what the exhibition lacks in depth of coverage it makes up for by providing insight into the aesthetic bias of the arts administrators of the Third Republic. |

|||||||||||

|

|

‘Plein-airisme’ of the Interior |

||||||||||

|

|

This clever curatorial play on the background colors of the installation and the atmosphere of the works themselves continues as the viewer exits the smaller exhibition rooms. In one marked transition, for example, the viewer leaves the intimacy of the red interior and emerges into a stark, white space that is dominated by scenes of mourning (Gustaf Theofor Wallén, The House of Mourning, 1892) and of quiet introspection (fig. 6). The cool colors of Anders Zorn’s Fisherman at St-Ives, Cornwall (1888) and of Otto Hagborg’s interior scenes at Pont Aven establish an emotional and psychological distance between the depicted figures and the viewer that is enhanced by the manner of their installation. These works also introduce another important theme of the exhibition, namely, the link between plein-airisme and both physical and intellectual interiority. |

||||||||||

|

The exhibition brings to the fore the various ways in which Nordic artists experimented with the idea of plein-airisme. What may be a familiar aspect of Impressionist depictions of nature and outdoor leisure scenes becomes a means of signifying something quite different in the hands of many of the artists included in this exhibition. Having presented the viewer with the plein-airisme associated with depictions of rural scenes, the focus of the exhibition changes to a ‘plein-airisme of the interior’. This may sound like a contradiction in terms, but as Frank Claustrat makes clear in his valuable catalogue essay, many of the genre scenes included in the exhibition are primarily concerned with conveying a ‘psychological atmosphere’. Landscape paintings that exploit a variety of lighting effects are paired with softly luminous interiors by artists such as Julius Paulsen, Peter Ilsted and Georg Achen (fig. 7). Further highlighting the link between natural and psychological landscapes, the curators cleverly juxtapose misty seascapes by Danish painter, Henry Brockman, with the depiction of solitary women by Paulsen, Achen and Ilsted. The viewer is invited to draw parallels between the imaginative life of the individual and dream-like meditations on nature. |

|||||||||||

|

|

Emergence of a Scandinavian ‘School’ |

||||||||||

|

|

While rural themes continue to dominate this section of the exhibition, the emphasis on winter scenes shows how artists such as Frithjof Smith-Hald and Frits Thaulow developed their talent for creating luminous visual effects from a restricted palette (fig. 9). Throughout the exhibition works by Thaulow, Edelfelt, Nils Wenzel, Johnnes Grimmelud and Anna Boberg exploit the lustrous textures of frozen landscapes and provide ample illustration of the point that snow is never simply white. |

||||||||||

|

In this section of the exhibition, the viewer is confronted with issues concerning the relationship between artistic practice and the creation of national identity. A crucial element in the recognition of the exhibited works as ‘Scandinavian’ is the broader critical response that they did, or did not, share during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Frank Claustrat’s catalogue essay traces the emergence of a Scandinavian ‘school’ in French art criticism. Focusing on an article published in 1889 by the art critic Charles Ponsonailhe (1855-1915) entitled “Scandinavian Artists in Paris”, Claustrat’s essay provides important insight into those aspects of the exhibited works that were thought to have been both ‘Scandinavian’ and ‘modern’. The recurrent themes are those of ‘plein-airisme’ and ‘light’. While focusing on these two aspects of Scandinavian painting, Ponsonailhe’s article does, however, illustrate a significant point of contrast between the critical reception of Scandinavian and French Impressionist painting. In contrast to nineteenth-century critiques of Impressionist plein-airisme, Ponsonailhe’s article praises the visionary qualities of Scandinavian painters, but also singles out their ability to provoke reflection and emotion in the face of nature. Rather than linking vision to sensation, such artists were considered to associate vision with thought. |

|||||||||||

|

|

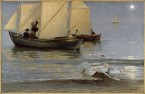

In illustration of Ponsonailhe’s arguments, the exhibition is fortunate to include an impressive large-scale work by Krøyer, Fishing Boats, Skagen (1884) (fig. 10). As discussed in the accompanying catalogue entry, Ponsonailhe considered this particular work to exemplify the lighting effects characteristic of Scandinavian plein-airisme. Painted by Krøyer during his stay in the Danish fishing village of Skagen, the suffusion of blue throughout the work, the interplay of reflections and merging of sea and sky cohere to form not just a seascape, but an ‘atmosphere’. What might have been a depiction of local fishermen at work becomes instead a metaphor of existential isolation as a result of the stylistic treatment of the subject. Ponsonailhe’s description of the work verges on a prose poem in its own right and praises the fusion of naturalism, luminosity and dream-like atmospheric qualities that came to be considered as the basis of Scandinavian symbolism towards the end of the century. |

||||||||||

|

Linked to the recognition of a Scandinavian school in art criticism of the late nineteenth century was the French state’s program of acquiring foreign art during the period. In her contribution to the exhibition catalogue, Annie Scottez-De Wambrechies discusses the crucial acquisition program of Léonce Bénédite (1859-1925) in the context of this enterprise. As director of the leading French museum of contemporary art of the period, the Musée du Luxembourg, and as creator of the museum of foreign art at the Musée du Jeu de Paume, Bénédite embarked on a series of acquisitions of Scandinavian works exhibited at the Paris Salon and at the various Expositions universelles that shaped both the collections of French museums and the public perception of Nordic art. |

|||||||||||

|

With their balance of academicism and plein-airisme, it is easy to see why the works included in this exhibition found favor with the guardians of French state collections. Whereas many French avant-garde painters of the late nineteenth century had a troubled relationship with the juries of the Paris Salon, the Scandinavian and Finnish artists included in Échappées nordiques not only sought out the prestigious exhibition spaces of the Salon and the Expositions universelles, but also enjoyed much success in them. While it would be unfair to link this success to the academic characteristics of many of the works, an argument can be made that a large number of Nordic artists absorbed precisely those aspects of contemporary French artistic practice that appealed to the conservative tendencies of Salon juries and national arts administrators. As this is one of the most interesting and distinctive aspects of the exhibition, it is a theme that merited more detailed treatment in the catalogue essays or, indeed, in the exhibition itself. By providing further detail of Bénédite’s other acquisitions on behalf of the Musée du Luxembourg and the Musée du Jeu de Paume, it would have been possible to provide viewers with a more precise understanding of how nineteenth-century French arts administrators sought to shape the holdings of national collections through the promotion of aesthetic trends they favored in painting both within France and abroad. |

|||||||||||

|

Nordic Symbolism |

|||||||||||

|

|

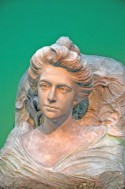

As the exhibition makes clear, the symbolism made manifest in this enterprise took a variety of different forms. Peter Nørgaard Larsen’s catalogue essay highlights the point that Danish symbolism of the 1890s is found not just in visionary landscapes, but in the sparsely populated domestic interiors of Ilsted, Achen and, above all, Vilhem Hammershøi. By contrast, the overtly religious aspects of the symbolic enterprise are summed up in the plaster relief Christ (1889) by Finnish sculptor, Ville Vallgren (fig. 11). This work is, however, also displayed in the context of the broader range of Vallgren’s sculptures, a small bronze and one of his series of high society Parisiennes from the turn of the century. Exploiting flower symbolism frequently associated with the depiction of women during the nineteenth century, the latter work includes a decorative relief that pre-figures Vallgren’s association with the art nouveau movement of the early twentieth century (fig 12). |

||||||||||

|

Several of Edvard Munch’s lithographs are displayed in the exhibition, including his portrayal of anguished individuals in works of 1896 and his psychologically searing portrait of French symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé. It is noteworthy, however, that these few relatively minor works were the only ones by Munch that formed part of the acquisition program displayed by the exhibition, one exception being the oil painting entitled Rodin’s Thinker in the Garden of Doctor Linde in Lübeck of 1907. As Marit Ingeborg Lange and Ann Falahat note in their catalogue essay, Munch’s works found little support in French art criticism of the time and, unlike many of his Nordic contemporaries, Munch chose to exhibit his works in the Salon des indépendents in 1896 rather than at the official Salon. Ultimately, it was amongst the avant-garde literary and artistic contributors to the magazine La revue blanche and in Siegfried Bing’s La maison de l’art nouveau that Munch was to experience some of his greatest Parisian successes rather than in the exhibition spaces championed by the Academy. |

|||||||||||

|

|

Images of nature dominate the final room of the exhibition. However, the viewer has been taken on a long journey from the introductory rooms displaying scenes of rural France. Epitomized by the visionary splendour of Anna Boberg’s fjords and mountaintops, and Edvard Diriks’s luminous clouds and seascapes that verge on abstraction, by the turn of the century Scandinavian and Finnish painting is shown to have transformed French naturalism into something distinctively its own (fig. 13). Ultimately, the works included in the exhibition cannot be reduced to a single style or school. However, the theme of plein-airisme runs through them all, making experimentation with light central to the depiction of a vast array of natural, spiritual and psychological landscapes. |

||||||||||

|

Kathryn Brown |

|||||||||||