The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

Constantin Meunier in Sevilla. De andalusische ouverture Catalogue (in Dutch and French) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

This past autumn, at about the same time that the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium presented a large-scale exhibition on the Cobra movement, it also presented a small yet very beautiful exhibition on Constantin Meunier in Seville (fig. 1). Although modest in size, not widely publicized, free of charge to visitors with a ticket for the museum’s permanent collection, and located in some of the museum’s more remote rooms, its content and quality were anything but modest. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Curated by Dr. Francisca Vandepitte, the exhibition displayed some 80 works of art from the relatively short period (October 1882-April 1883) when the Belgian artist, Constantin Meunier (Etterbeek, 1831 - Elsene, 1905), then already fifty-one years old, lived in Seville. Then known primarily as a painter of historical pieces and religious scenes, Meunier was on the brink of success as an artist of working class and industrial subjects. This was an especially productive and stimulating period that undoubtedly influenced the style and content of his future work. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In Seville, Meunier created about ten paintings and some hundred drawings and sketches. Around three-quarters of the works displayed in Brussels had never been exhibited and/or published. They came mainly from collections of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium and the Constantin Meunier Museum (part of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium), as well as from the Ixelles Museum and the Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Antwerp. In addition, some works of art were borrowed from mainly Belgian private collections. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Prior to the exhibition, the works of art were examined and restored (if necessary), resulting in a coherent and well-focused thematic exhibition and catalogue. Meunier’s lively correspondence from Seville provided a storehouse of information for the researchers, making this period the best documented of his career.1 His family preserved over a hundred letters, some four hundred pages in all, mainly to his wife Léocadie but also, for example, to Edmond Picard.2 Some of these letters were decorated with sketches and offer excellent insight into Meunier's experiences, the people he talked to, the things he saw and thought, and even what he ate (although the Spanish cuisine did not really appeal to him, he gradually lost his disgust of olives). The letters record Meunier’s life and work in Seville almost from day to day, bringing to life his time there. Furthermore, they made it possible for the researchers to contextualize, date precisely, and identify the works of art he created there. For example, the previously unidentified sitter in a small privately-owned portrait, exhibited in a display case, was discovered to be Torero Frascuelo (cat. 38, fig. 2). Such rich textual supplements to the visual materials are unique and reminiscent of Vincent van Gogh’s many letters to his brother. Actually displaying some of these letters would have provided visitors with a glimpse of the research that goes on behind an exhibition like this. Moreover, being able to read the sometimes marvelous and humorous letters might have intrigued the public as much as they excited the researchers. Fortunately, the letters were used to provide each room with a well-chosen quotation (in Dutch and in French) (fig. 3). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The simple yet stylish exhibition rooms were arranged by topic, referring to the commission, the places and subjects that occupied Meunier in Seville: 1) the commission, the life in the cathedral, 2) street life, 3) cockfights, 4) the corrida, 5) the tobacco factory, 6) Semana Santa, and 7) flamenco. The works of art were chosen and displayed consistently throughout, with the single exception of Daken te Sevilla (Rooftops in Seville) which is located in the room about cockfights. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

In the first room, a monumental painting and a brief introductory text in Dutch and in French awaited the visitor (fig. 4). Although it presented a clear insight, this text may have been somewhat too brief as there was no other information available in the exhibition rooms. The other rooms contain only short quotations from Meunier’s letters to inform the visitor (fig. 5). The emphasis thus is on the works of art, which, considering their high quality may have been the right choice. For further reading, a concise and reasonably-priced catalogue was available in the bookshop. Notwithstanding its scholarly nature, it has a fairly attractive design and many colored illustrations. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The first room of the exhibition was dedicated to the commission issued by the Belgian government which was the purpose of Meunier’s trip to Seville. He was asked to make a full-size reproduction of a painting in the cathedral of Seville, The Deposition from the Cross (1547) by the Brussels-born artist Pieter De Kempeneer (1503-1580), in Spain known as Pedro Campaña. This reproduction, now displayed for the first time, was intended to be exhibited at a planned, but much-contested and never-realised Musée des Copies, which would, following a Parisian initiative, represent ‘Belgian’ artworks abroad via reproductions (fig. 4, cat.1). Not very fond of traveling, Meunier arrived in Seville in October 1882, accompanied by his son Charles, an engraver, but due to unexpected practical circumstances, he could not start the copying process until late December, much to his annoyance. As a father of four, he accepted the commission primarily to earn money, but he hoped to be finished with it as quickly and efficiently as possible. In contrast to many of his contemporaries and compatriots, Meunier never intended to discover Spain, its pictorial tradition and its picturesque qualities; he was therefore barely prepared for what he was about to encounter. Upon completing the reproduction, both father and son returned home immediately. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This first room also exhibited drawings about everyday life in and around Seville’s cathedral, as observed by Meunier from the scaffolds he used while copying the painting. For example: beggars (cat. 4), shy choristers (cat. 6), processions (cat. 7), a priest smoking a pipe (cat.11, carrying the inscription, in French: Strange customs. A priest quietly smoking pipe !3) (fig. 6). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Meunier’s time in Seville thus lasted considerably longer than he had anticipated. In the meantime, while staying at several hotels with his son, he got to know the city and its inhabitants. With growing enthusiasm, he portrayed contemporary life and work in the Andalusian city, focusing mainly on beggars and vendors in the streets and markets, the bloody cock and bull fights, women manufacturing cigarettes in the tobacco factory, flamenco dancers in cabarets (café-chantants), and the somewhat eerie processions during the Semana Santa (Holy Week). The following galleries were dedicated to these subjects. Each room contained a quotation, at least one painting and some well-chosen drawings (fig. 7). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The drawings may very well have been this exhibition’s most amazing revelation, as they show Meunier’s versatility. He mastered a wide array of graphic techniques and was able to tell stories through his drawings. Both detailed preliminary studies (for example, cat. 6) and quick sketches are displayed; and drawings in both a rather smooth academic style and others in a much looser, free, spontaneous style, with for example a mass of people suggested by nothing more than a few playful, curly strokes of the pen (figs. 8, 9). In one of his letters, Meunier mentions his frequent use of “hastily drawn sketches.”4 His most experimental drawings appear to presage Picasso. Meunier was versatile as well when it came to the materials he used: he drew with pencils, charcoal, pens, brushes, ink wash and watercolor, also combining these materials and techniques. Unfortunately, no mention is made of the materials used in the descriptions accompanying the works of art. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Although Meunier initially grumbled consistently about his stay in Seville, some drawings (as well as some letters) provide evidence of a certain joy and even a touch of humor: with a few quick strokes he turned a sun into a smiling face (fig. 10, cat. 33: Terugkeer uit Triana [Return from Triana]). Also, the drawing of his son Charles, wearing checked pants and walking towards the spectator, while blowing to warm his hands in the cold cathedral where, in the background, his father is working on the reproduction, makes one smile (fig. 6, second painting from the right). Meunier’s attitude changed for the better shortly after he was able to begin painting his reproduction. Then he wrote: “Sapristi! What a pleasure to paint this”5 and “I have so many ideas, and so little time to carry them out!”6 This reveals another side of an artist who has come to be known as a serious, rather melancholic man, depicting mainly gloomy and dejected subjects. You see an enthusiastic Meunier, who eventually came to enjoy his time in Seville. Yet there as well, Meunier showed his melancholic side, for example, when picturing the corridas (bullfights). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Meunier portrays his subjects in Seville as a realist rather than a tourist. It is possible, however, that his view was influenced by romanticized literary and musical traditions, such as that of Carmen.7 As early as 1878, Meunier turned his attention to labor and the tough daily existence of industrial southern Belgium (Walloon). Although conditions were not quite the same in Seville, there too he paid scant attention to the beau monde (for example, he drew only a few sketches of women wearing a mantilla, a silk scarf worn over the head and shoulders). Instead, he shifted his focus to the worker’s ‘typical’ everyday life and amusement, portraying this with warm colors and a remarkably loose, nearly impressionist way of applying paint to the canvas. Meunier observes and registers, reporting what he witnesses, not from a position of superiority, but with involvement and deep empathy. His subjects are considered with a sharp eye, deep fascination and more often than not, with sympathy and close affinity. “La Carita!!!”, an inscription on his drawing of an imploring beggar at the cathedral’s entrance, may be considered one of the most striking examples of the latter (cat. 4). Both physically and mentally, Meunier knows how to move among different classes and environments. New opportunities arose when he was introduced into Seville’s culture-oriented upper class. His letters mention encounters with a professor, a teacher, a picador (a kind of bullfighter), the owner of a tobacco factory, a barkeeper, etc.8 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

In the gallery on street life, old beggars, a blind town crier, fishmongers, a wine trader, a knife maker, musicians and mule drivers were all portrayed (fig. 11). Especially at the start of his stay in Seville, Meunier was intrigued by the ancient town center and particularly by the activity in and around the Calle Sierpes, not so much because of the picturesque nature that many of his colleagues sought there, but rather because of the astounding coexistence of rich and poor. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

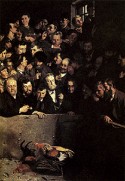

In the galleries featuring cock and bullfights, or corridas, the focus shifts to the ‘typical’ local amusement: the cruel battles between and with animals (figs. 12, 13). Meunier was fascinated by the frenzied crowd, consisting of people from all classes; he was also compassionate towards the suffering animals, as exemplified in Het knekelhuis (The Charnel House) (cat. 46), his later sculpture Oud Mijnpaard (Old Mine Horse; 1893), and in some letters. He described corridas as being “interesting and bizarre, but at the same time horrible. I have seen 7 or 8 horses and 3 bulls killed. … Quite a fanatical affair!”9 In a letter dated December 17, Meunier admitted feeling sympathy for the bull, because it is rarely fated to emerge victorious. About the heated cockfights he wrote to his wife: “I witnessed a cockfight yesterday. I was tipped off in the hotel, as they know that I am looking for scenes that are typical of this city. ... Hundreds of people from all classes are seated on benches. ... The crowd goes wild. … The poor animals are completely covered in blood. Barbaric as it may be, it appears to be quite common here.”10 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Meunier prepared for his painting of the cockfight (cat. 69; fig. 12) with several drawings (cat. 70-71) and oil sketches. Recurring in these preliminary sketches are brightly accentuated arches, which make it appear as though the central row of people have halos around their heads. In the definitive painting, the figures in the background, quite roughly sketched, seem influenced by Francisco de Goya’s black paintings, rather than by Emile Claus’s depiction a few months earlier of the same theme, but then situated in Flanders: Hanengevecht in Vlaanderen (Cockfight in Flanders) (fig. 14). Claus’s painting, exhibited both at the Paris’ and the Antwerp Salon in spring 1882, focuses more on the individuals present, who look more disciplined, distinguished and calm than in Meunier’s work. Claus’s painting was indeed initially commissioned as a portrait gallery of the noblemen of Waregem, and is thus less realist and more conservative than Meunier’s depiction of the theme. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Meunier viewed the corridas with a similar combination of attraction and horror, yet always with great empathy. Here too, Goya could be named as a possible source of inspiration, namely his La Tauromaquia (published in 1816). On the one hand, Meunier portrays picadors and toreros triumphantly administering the fatal thrust to the bull’s shoulder blades (cat. 40-42, La Muerta), or on a horseback, posing in the blazing sun (cat. 45, Picador in Seville) (fig. 15). He also grants bull herders (cat. 35-37) a certain level of greatness, intertwining, almost merging, them with the figure of Don Quixote as represented by Honoré Daumier in the 1860s. On the other hand, Meunier shows the painful aftermath of events. This is very clear in the extremely loosely painted Het knekelhuis (The Charnel House,cat. 46). In the background is a bleeding bull, fallen in battle, and in the foreground lie roughly sketched dead horses. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In the galleries showcasing the tobacco factory and flamenco, women appear in the picture, not entirely in the same way as in many nineteenth century Spanish and French paintings (figs. 16-18). It would be inaccurate to suggest that Meunier’s cigar makers and flamenco dancers are portrayed unattractively (see, for example, the woman in the foreground of Tabaksmanufactuur te Sevilla (Tobacco Factory in Seville) (cat. 58), with her strap slipping off her shoulder) (fig. 19). Meunier does not, however, emphasize sensuality or idealize his women. Instead, he tried to show real bodies, working, sweating and dancing (fig. 20). He did not let the women in his paintings pose, nor was he searching for erotic postures. In some sketches (cat. 52, 53, 60, 62), women are depicted in anything but a flattering way (fig. 21). In one sketch (cat. 52), a hand even resembles a claw. Meunier registered the things he saw, heard and smelled, with both an unmistakable fascination for these ‘other’ women, and with a certain disgust. Or was the latter mainly intended to comfort his wife? |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In her letters, Léocadie had interrogated him about the evenings he spent in the cabarets in the company of his compatriot and fellow painter, Alfred Cluysenaar, or the Parisian composer Emmanuel Chabrier, and about the thousands of “Carmens” working in the tobacco factory. Meunier described the cigarreras as follows: “The warm colors of their heads contrast with their red or orange headscarves. It truly is an adorable play of colors! Do not think that these girls look seductive. Most of them are ugly and sunburned, but there is something wild and mysterious about them…”11 Some days later, he writes, undoubtedly in an attempt to further convince his wife: “Rest assured: one would have to be really desperate to find these girls attractive; they are completely permeated with the lingering tobacco smell, not to mention the other odors intermingled with it. Most girls are as brown as old leather and as dry as a goat skin.”12 Twenty years earlier, Théophile Gautier had described the cigarreras of that same factory quite differently: “Most of them were young, some of them were gorgeous. Their clothes were so ragged that it was not really difficult to take a peep down their dresses.”13 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Moreover, Meunier was fascinated by the factory building itself: the Real Fabrica de Tabacos, inaugurated in 1758. Both to his wife and to Edmond Picard, Meunier expressed his admiration of the monumental building with its impressive vaults, of which he did a separate study in oils (fig. 22, cat. 64): “I have seen something magnificent. Having two or three days to spare before starting the reproduction, I went to the tobacco factory. That was a splendid idea because there, the artist within me again awoke… Material for a new and exciting painting. … For a moment I was reminded of Bizets Carmen, but that pales in comparison with the savage and weird sight of those enormous vaulted rooms, dimly lit, where at least six thousand women are hard at work!!!”14 Meunier made an agreement with the factory owner who allowed him to sketch for one or two hours a day, while supervisors made sure that he would not be disturbed. The tobacco factory was one of the first major industrial buildings in Europe and the largest of its kind in Spain. Many travelers, artists and writers, such as Prosper Mérimée, Alexandre Dumas, Gustave Doré, Edgar Quinet, and Jules Clarétie, were inspired by it. Meunier, however, was unaware of this and believed he had discovered a unique subject: “I don’t have the slightest desire to paint the same boring and low topics that my Spanish colleagues paint. Apart from these common things, there are other themes with something mysterious and distinctive about them, that you don’t find just like that. Only now do they start to make an impression on me. Everything is so strange and painful to our painter’s eyes, which are used to the damp, strong northern colors, that we are taken aback by these dazzling and unfamiliar scenes.”15 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Finally, the Semana Santa (Holy Week) gallery showed once more Meunier’s fascination for what is different and unknown, via a typical, ancient local custom that was strange to him (fig. 23). Near the end of his stay in Seville, he witnessed the religious festive week from March 18 until March 23. He was especially intrigued by the procession of silence on Maundy Thursday and the penitents’ characteristic pointed masks (as also seen on Goya’s Procession with flagellants, 1812-14). Meunier captured the mysterious and rather spellbinding, dramatic atmosphere of the event. (fig. 24, cat. 74, 75) A lovely sketchpad is also on display in this room (fig. 25). |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The organization of the catalogue is slightly different from the exhibition. Like the exhibition, it is also divided thematically, but according to the specialties of the five authors involved. The beautifully illustrated soft-cover book presents five captivating scholarly essays, approaching the corpus from different perspectives. Nevertheless there is some (inevitable?) overlap and repetition between the articles. Almost all authors draw inspiration from Meunier’s correspondence. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Francisca Vandepitte wrote the introductory article entitled In de voetsporen van Pedro Campaña. Constantin Meuniers zending naar Sevilla (In the Footsteps of Pedro Campaña. Constantin Meunier’s Mission to Seville), in which she situates Meunier’s time in Seville within the scope of his career, the aim and history of the Musée des Copies, and Belgian and international painting at the time. Vandepitte elaborates on the commission issued by the Belgian government that took Meunier to Seville, and the manifold practical difficulties involved in it, Meunier’s experiences during his stay, and the extensive correspondence he carried on from the city, as well as the controversy in Belgium at the time surrounding the plans for the Musée des Copies. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The other articles each discuss one or more particular themes. In her essay, Over nobele bedelaars, de corrida en café El Burrero (On noble beggars, bull fights and Café El Burrero), Sura Levine examines three iconographic themes: beggars, the corrida, and flamenco in El Burrero. In a fascinating manner, she weaves formal analyses with historical research. On the basis of historical documents such as engravings and photographs, she manages to prove that the painting formerly known as Café del Buzero shows the spacious Café El Burrero, a cabaret opened in 1881 by flamenco singer Ojeda Rodríguez. Pierre Baudson’s essay, Vrouwenarbeid en mannenvermaak. Tabaksfabriek in Sevilla en Hanengevecht (Women’s Work and Men’s Amusement, ‘Tobacco factory in Seville’ and ‘Cock Fights’), treats two other iconographic themes. Abundantly using Meunier’s correspondence, Baudson discusses the genesis and reception of both paintings and the other artists who, before Meunier, were intrigued by Seville’s tobacco factory. In his article, De Semana Santa van Sevilla zoals Constantin Meunier ze heeft gekend (Holy Week in Seville as seen by Constantin Meunier), Carlos Colón, a professor in Seville, describes the Semana Santa tradition in the Andalusian city, from the Middle Ages up to Meunier’s time. To conclude, Norbert Hostyn situates Meunier’s stay in Spain in relation to ‘other Belgian artists in Spain 1800-1900’. After a short introduction, he describes chronologically, one by one, the trails of twenty-four Belgian artists in Spain, from Florentin Decraene (1783-1852) to Theo Van Rysselberghe (1862-1926), devoting most attention to François Bossuet, François Stroobant, François Musin, Carlos De Haes, Félicien Rops and Emile Claus. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Less successful is the catalogue’s lack of a table of contents, index and bibliography. Also a concise catalogue raisonné, albeit with small black-and-white reproductions, of the Seville paintings, now spread throughout the entire book, would have been convenient. Perhaps the exhibition’s rather modest intention (and presumably budget) had something to do with this. Indeed, no page goes unused, and the small catalogue was published as the third issue of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium’s series (Cahiers). Nevertheless, the catalogue is definitely a praiseworthy record of a successful exhibition, contributing to a nuanced and complete knowledge of Constantin Meunier’s oeuvre. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Marjan Sterckx, Ph.D. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The author wishes to express her thanks to Dr. Francisca Vandepitte, curator of the exhibition, and to Dr. Sura Levine for guiding me through the exhibition, and to Mrs. Vandepitte for supplying some of the photographs in this review and for permitting their reproduction. 1. Meunier’s time in Louvain also has been well documented. See M. Sterckx, ‘Constantin Meunier and Leuven (1887-1897). A love-hate relationship’, in: H. Van Gelder (ed.), Constantin Meunier. A dialogue with Allan Sekula, Lieven Gevaert Research Centre for Photography and Visual Studies-series, vol. 2 (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2005), 19-58. 2. In his first letter to her, Meunier asked his wife to save his correspondence, so as to remember his journey. Some of Meunier’s letters were published in L’Art Moderne by Edmond Picard in 1882-1883. Picard entitled them Tra los montes, inspired by Théophile Gautier’s travel book on Spain by the same name from 1843 (which was reissued as Voyage en Espagne in 1845). Le Samedi published unabridged about half of the letters from Seville in 1905-1906. 3. Drôle de moeurs. Un prêtre fumant tranquillement la pipe! 4. Letter from Constantin Meunier to Léocadie Meunier, February 17, 1883; as quoted by Pierre Baudson in the catalogue, 84. 5. “Sapristi! Quel plaisir de peindre ça”; Letter from Constantin Meunier to Léocadie Meunier, December 29, 1882; as quoted by Francisca Vandepitte in the catalogue, 19. 6. Letter from Constantin Meunier to Léocadie Meunier, January 10, 1883; as quoted by Pierre Baudson in the catalogue, 83. 7. Meunier was familiar with Georges Bizet’s 1875 opera, based on Prosper Mérimée’s 1845 novel of the same name. 8. See, for example, references in the letter to Léocadie Meunier, dated November 2, 1882: “That’s what I was told yesterday by a teacher I just met. He’s a very nice person, and progressive as well.” Also, in the letter to Léocadie Meunier, dated March 17, 1883: “I met a fairly good picador today. […] I promised to do a portrait of him.” Quoted by Sura Levine in the catalogue, 36-37. 9. Letter from Constantin Meunier to Léocadie Meunier, October 8, 1882; as quoted by Sura Levine in the catalogue, 35-36. 10. Letter from Constantin Meunier to Léocadie Meunier, January 2, 1883; as quoted by Piere Baudson in the catalogue, 82. 11. Letter from Constantin Meunier to Léocadie Meunier, October 26, 1882; as quoted by Pierre Baudson in the catalogue, 68. 12. Letter from Constantin Meunier to Léocadie Meunier, November 2, 1882; as quoted by Pierre Baudson in the catalogue, 69. 13. Théophile Gautier, Voyage en Espagne (Paris: Charpentier, 1859) p 336; as quoted by Pierre Baudson in the catalogue, 69. 14. Letter from Constantin Meunier to Léocadie Meunier, October 26, 1882; as quoted by Pierre Baudson in the catalogue, 68. 15. Letter from Constantin Meunier to Léocadie Meunier, November 1882; as quoted by Pierre Baudson in the catalogue, 74. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||