The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

An American in Switzerland: Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848 – 1907): scultore Americano dell'Età d'Oro at the Museo Vincenzo Vela Exhibition at the Museo Vela, Ligornetto (canton Ticino, Switzerland) Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907), scultore americano dell'Età d'Oro |

|||

| It was a summer of Americans in Europe—not in the usual sense, as in the tourists on the two-hour lines at Versailles or the dazed throng in front of La Joconde at the Louvre—but in the nationality of the artists presented in exhibitions. Included among these were well-presented retrospectives in Paris of American modern and contemporary sculptors such as Dan Flavin at the Musée d'Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, David Smith at the Centre Georges Pompidou, and a survey exhibition entitled Los Angeles 1955-1985: Birth of an Artistic Capital, also at the Pompidou. While not all of the exhibitions from this American invasion were first-rate (American Artists at the Louvre was a largely forgettable presentation of haphazardly-chosen works), the trend of showcasing American artists at European museums seeped even across the border into Switzerland. | |||

| A special exhibition of works by the Irish-born, American sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens was memorably displayed this summer at the Museo Vincenzo Vela in Ligornetto (canton Ticino), one of Switzerland's oldest federally funded museums. Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907): scultore Americano dell'Età d'Oro (Sculptor of the Gilded Age) marked the first time that the Swiss public was introduced to Saint-Gaudens, a contemporary of Vincenzo Vela (1820-1891), Switzerland's most prominent sculptor at the turn of the century. | |||

| The show was conceived by the Museo Vela in collaboration with the Trust for Museum Exhibitions in Washington D.C. and the Augustus Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site and Museum in Cornish, New Hampshire. Like the museum dedicated to Saint-Gaudens in Cornish, the Museo Vela—at one time the sculptor's working studio and recently restored by the Swiss architect Mario Botta—contains one of the largest and best preserved public collections of original plasters, personal effects, drawings and bozzetti of any one sculptor in Europe. The exhibition contained sixty-three works ranging from models to finished bronzes in the round and in relief. Included in the show were examples of Saint Gaudens' youthful work as a cameo cutter, the métier that planted the seeds for his later work in large-scale relief sculptures. | |||

| Saint-Gaudens and Vela, as far as is now known, never met, but they were both major figures of the realist (or verismo) movement in sculpture that saw its greatest intensity in the late nineteenth century. Saint-Gaudens surely saw Vela's Last Days of Napoleon I at the Universal Exhibition of 1867 in Paris (fig. 1), a work that immediately reminds one of Saint-Gaudens' own Abraham Lincoln Seated of 1897 for Grant Park in Chicago (fig. 2). The two works, with their strikingly similar poses and largesse, both show these two deeply reflective politicians at crucial moments in their lives; Saint-Gaudens' Lincoln is as much a man in his final days as is Vela's Napoleon. The pose was one used in other sculptures by Saint-Gaudens, including his Peter Cooper Monument (1897, Cooper Square, New York). The American sculptor had made a special trip, his first to Paris, to begin to study at the École des Beaux-Arts and to see the exhibition. Vela, for his part, had won a first prize medal for Last Days and earned his reputation at that venue. Saint-Gaudens' connections with Europe and his admiration for Renaissance art were solidified during the five years he spent studying in Paris and Rome before his return to New York in 1872. During that first European sojourn, Saint-Gaudens was the first American to enter the atelier of François Jouffroy at the École des Beaux-Arts. Later, between 1897 and 1900, Saint-Gaudens lived in Paris, where his works were shown at the Salons and at the Exposition Universelle of 1900. At that time he also helped to spearhead the American Academy in Rome. Although we do not have any documentary evidence that the two artists knew each other directly, it seems likely that they were familiar with each other's work, as Saint-Gaudens' first-hand involvement in the world of European sculpture in Paris and Italy, where both he and Vela worked, would suggest at least such a familiarity. | |||

| It is not without historical consequence that an exhibition of Saint-Gaudens' work was displayed in Switzerland. The sculptor had traveled through the country in 1869, a trip that he remembered fondly later in his life, giving this Swiss exhibition of his work great validity. In his Reminiscences, Saint-Gaudens recalled this trip, taken with friends he had made in Jouffroy's studio. Alfred Garnier, one of the friends who accompanied Saint-Gaudens through Switzerland, wrote in 1907 that "Augustus often remarked to me that our journey through the Juras and in Switzerland was one of the finest he ever had, incomparable to any others. I agree with him."1 Although the sculptor had not made it to Vela's part of Switzerland in Ticino, he had visited Basel, Bienne, Geneva, Lausanne and Neuchâtel, mostly on foot. | |||

| There were also similarities in the two artists' approach to monumental sculpture and verismo portraiture. Along with his immediate predecessors, J.Q.A. Ward and Henry Kirke Brown, Saint-Gaudens introduced naturalism to American sculpture (in Saint-Gaudens' case it was a naturalism of the French variety), at a time when neoclassicism still permeated the medium. Neither Vela nor Saint-Gaudens cared much for the non-finito style favored by Rodin, their French rival; they were both more inspired by Donatello, the first modern realist sculptor, than by any of their contemporaries. Both focused their oeuvres on the creation of monuments to modern heroes and patriots, and yet both found time to portray some of the most beautiful and wealthy people of their age. | |||

| As can be seen from the installation views reproduced here (figs. 3-6), the exhibition was not in anyway excessive; in fact most of the works were choice selections borrowed from the Augustus Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site and Museum in Cornish, which was temporarily closed in 2006 for renovations. The objects exhibited at the Museo Vela benefited from the cool, natural lighting and open gallery spaces. A delicate shade of light blue was used on the pedestals and on the wall text, framing some of the works, adding a special touch and unifying the rooms of the exhibition. The sparing selection was completely appropriate to the Museo Vela: as an exhibition meant to introduce the Swiss public to an American artist largely unknown in Europe, it was correct to keep the exhibition light and focused. The installation worked very well with the sculpture, a medium which is often difficult to exhibit successfully precisely because of the limited colors of the works themselves. The light blue color of the pedestals and exhibition design continued to the catalog of the exhibition. It added a bright, soft and welcome deviation from the stark and repetitive white and brown tones of the sculptures on display. | |||

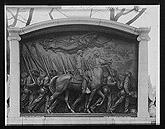

| The exhibition's curator, Dr. Gianna A. Mina, who is also the director of the Museo Vela, ventured some intriguing comparisons between Saint-Gaudens' and Vela's work, juxtapositions that were not without serious thought and merit. One of the most interesting of these was a comparison between Saint-Gaudens' Shaw Memorial, begun in 1897 (fig. 7, presented in the exhibition photographically alongside some of the many bronze studies for the 54th Regiment Soldiers' heads) and Vela's Victims of Labor of 1882 (fig. 8). Although fifteen years separate their conception both are large scale, high relief sculptures, both were destined for prominent public display, and both deal with the theme of death and the modern hero. | |||

| What is striking, through, is their different approach to the presentation of the theme of death. Saint-Gaudens' use of an allegorical figure above or alongside many of his heroic notables (seen in the Shaw Memorial but also in his Sherman Memorial and his Monument to Admiral David Farragut in Madison Square Park, New York) is certainly due to his deep admiration for Renaissance art, but it also says something about Saint- Gaudens' American public. Vela's Victims of Labor, a memorial to the fallen workers who died during the construction of the Saint Gotthard railway in the Swiss Alps, felt that his heroic workers and the dead laborer needed no allegory, no angel of death, to assure the public of this worker's safe passage into the hereafter. Vela, a hyper-realist bar none, would not have allowed for such seemingly trite symbolism of allegorical figures; the expressions and gestures of the figures alone depict the heroic qualities of the common man. Saint-Gaudens' American audience, however, needed the allegorical figure to soften the severe gloom of his memorial, a very real image of the first all-black regiment and their white general Robert Gould Shaw marching towards their imminent deaths (or possibly they are already dead, their spirits being led safely to the great beyond). Their stark fate would have been much too harsh for a public that had physical and psychological wounds still too raw from the war to accept art without an allegorical buffer. | |||

| And yet, maybe the Swiss public wasn't so different from the American one: Swiss authorities found Vela's Victims of Labor too stark and did not cast Vela's relief into bronze until 1932, more than forty years after the artist's death. Saint-Gaudens' angel of death in the Shaw Memorial, who floats above the soldiers and the general, is their protective guide; she assures the viewer of the safety of their final voyage. It was this mixture of realism with allegory that was Saint-Gaudens' trademark, one that ultimately became his greatest contribution to American sculpture. | |||

| Another striking aspect of Saint-Gaudens' work underscored in the exhibition was his close working relationship with the architect Stanford White and, thus, the sculptor's relationship with architecture, or, possibly more importantly, the medium of sculpture and its relationship to architecture, truly the hallmark of the American Beaux-Arts ideal. Saint-Gaudens met White in 1875, marking the beginning of a long-standing partnership on a variety of projects including the sculptor's Diana for White's Madison Square Garden as well as the architect's exedra for Saint-Gaudens' Farragut. Collaborations between Saint-Gaudens and White were presented in the exhibition and included the bronze bas-relief of Dr. Henry Schiff from 1880; a high-relief posthumous portrait from 1888 of Louise Miller Howland (see discussion below); and a bronze cast in the round of Diana from the collection at Cornish. Saint-Gaudens' high-relief portrait of White's wife, Bessie Smith White—a bronze cast after the marble that was given to White as a wedding present in 1884—was also exhibited. A portrait of Saint-Gaudens' own wife, Augusta Homer Saint-Gaudens, was shown at the exhibition in a bronze sketch, but his mistress Davida Johnson Clark was technically presented three times, in a portrait bust and in the artist's Diana and Amor Caritas, for which the plaster bust of Clark's portrait served as the model. | |||

| The strength of the exhibition lies in the relief portraits by Saint-Gaudens that are excellently presented. The ultimate expression of Beaux-Arts eclecticism, with its architectural mounting (by White), Latin textual inscription (ET VXOR ET MATER DVLCISS MA ET GENEMERENS / Most sweet and worthy wife and mother), and illusionism (seen in the piano and the overlapping pages of the sheet music), can be seen in Saint-Gaudens' posthumous portrait of Louise Miller Howland, wife of a New York Court Judge (fig. 9). Her intertwined fingers and delicate hairs behind her tiny ears animate the sculpture with a breath of life. Besides being shown through the Latin inscription as a "worthy wife and mother," Howland is presented astride her piano and sheet music, identifying her as having a talent for music, which, as in numerous portraits of women from the Renaissance, is a code for artistic intellect. (Saint-Gaudens uses the same code in his relief portrait from 1890 of Violet Sargent, the sister of John Singer Sargent, shown seated and tuning her guitar.) Fittingly, Saint-Gaudens surrounds Howland in a Renaissance-inspired niche designed by White; immediately one recalls the niches of altarpieces in Italian churches, which often contain portrait sculptures of martyrs and saints. Certainly in the context of this portrait, Howland is meant to be seen as such a divine figure. It would be difficult to find a more stunning relief portrait of the period from Europe or America. | |||

| The presentation of Saint-Gaudens' work at the Museo Vela and the texts that accompanied the exhibition (including an exhibition catalogue in Italian with essays by Gianna A. Mina, Henry J. Duffy and John H. Dryfhout; and a special issue of the museum's journal, Casa d'artisti, with an essay in Italian entitled "Vincenzo Vela e l'America" by Nancy J. Scott) focused on the unexplored international connections within the history of nineteenth-century sculpture, a necessary project. The exhibition presented a long-overdue discussion of the connections between American sculptors and their European counterparts outside France. While the Parisian influence on late-nineteenth-century American art cannot be ignored, this exhibition sought to contextualize American sculpture within the larger scope of European sculptural production at the turn of the century. American art found respect in Europe this summer and the Saint-Gaudens exhibition, above all others, represented the artist's country with pride. | |||

| Caterina Y. Pierre, Ph.D. City University of New York – Kingsborough caterinapierre[at]yahoo.com and cpierre[at]kingsborough.edu |

|||

| Related Links: http://www.nps.gov/saga http://www.museo-vela.ch/ |

|||

|

1. Augustus Saint-Gaudens, The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens. 2 Vols. H. Barbara Weinberg, Ed. (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1976), Vol.1, p. 91-2. |

|||