The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

Please note: selected figures are viewable by clicking on the figure numbers which are hyperlinked. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Roger Marx, un critique aux côtés de Gallé, Monet, Rodin, Gauguin…" [An exhibition organized with the collaboration of the Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Exhibition catalogue: Roger Marx, un critique aux côtés de Gallé, Monet, Rodin, Gauguin…. Nancy: Ville de Nancy, Éditions Artlys, 2006] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| An awareness of creative Republicanism at the service of the visual arts has become strikingly apparent in the recent exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts and the Musée de l'École de Nancy dedicated to the career, ideas and collecting of Roger Marx, one of the most enlightened supporters of the visual arts during the Third Republic. Roger Marx spent his entire career as a fervent promoter of "new" art; he was also a major proponent of the idea that all the arts should be regarded as equal—one of the basic tenets of the art nouveau movement at the close of the century (fig. 1 and fig. 2). Whether he wrote for newspapers, completed essays for exhibition catalogues, supported group shows, collected works of art for himself or lobbied behind the scenes as an advocate for various artistic causes, Marx recognized that the art of his own native region—Alsace-Lorraine and specifically the city of Nancy—also needed a strong and enlightened sponsor. He wanted the artists of his region to compete with Paris and other artistic centers outside of France. Advocating these positions with amazing dexterity and clear insight, Marx developed an intimate awareness of artistic creativity from frequent discussions with regional artists such as Émile Gallé, Émile Friant, and many others who became his close friends. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In examining all aspects of Marx's career, and his myriad interests, this compellingly didactic exhibition was not only visually stimulating, but made visitors aware of the varied issues that Marx advocated. At the same time, the rich diversity of artistic creativity in The Third Republic became explicitly apparent. Marx, as a talented and forthright supporter of Third Republic creativity and ideology, did his best to promote creativity in all areas of the arts by remaining open and enthusiastic to everything as long as it was aesthetically excellent. These aspects were in evidence in the Nancy exhibition. Issues raised will be discussed section by section as the organization of the show followed a strong thematic framework that was abetted by a thorough grounding in history. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Roger Marx in the Context of the Graphic Arts While visitors to the exhibition were to start their visit with the Introduction to Roger Marx's life and career—situated on the first floor of the Musée des Beaux-Arts—one could, as this reviewer did, start with Marx's interest in the graphic arts examined in a section of the exhibition shown separately in a part of the museum dedicated to the graphic arts. In this extensive and well-rounded segment of the exhibition, Marx's early commitment—he showed an interest in drawing and printmaking soon after his arrival in Paris in 1883—to all the major printmakers of his era was carefully established. By highlighting his support of the publication of L'Estampe Originale, and by including works by well-known artists and those not yet fully recognized, the organizers of the exhibition revealed how Marx was committed to all types of print techniques. His familiarity with new techniques, the color revolution in lithography, and the appearance of woodcuts as a major creative advance, revealed Marx's telling perspicacity as one of the most enlightened print connoisseurs of his generation. The importance of L'Estampe Originale to the print renaissance, and the ideas behind it, was extremely well represented in the exhibition (fig. 3; figs. 4,5,6) and highlighted the ways in which printmaking tendencies were dominant in the era, making the publication a touchstone for individuality. Marx's introduction to the publication further situated his writings at the heart of the debates of the 1890s when the print medium became so liberalized and diverse. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In this section of the exhibition, perhaps as a slight afterthought, Marx's involvement with the craze for all things Japanese was examined. As a colleague of Siegfried Bing (one of the major promoters of Japonisme), and a contributor to the monthly periodical Le Japon Artistique, Marx was considered a significant Japoniste (fig. 7). He was also a collector of Japanese prints and a supporter of all artists who learned from Japanese culture and art. A print by Henri Guérard, positioned next to works by Hiroshige and Hokusai, reinforced this connection although, perhaps, more could have been done in the show and in the scholarly catalogue on this aspect of Marx's interests, especially since it was so important to the arts of the period and to the close relationship that existed between Marx and Bing.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The value of L'Estampe Originale was signaled with the inclusion of Toulouse-Lautrec's compelling image of the performer Jane Avril examining a print at the printer's studio where the portfolio was completed. This cover design remains the best-known work, although it does not sum up all of Marx's involvement with printmaking contained in the publication. Other major works from this portfolio were also included, allowing viewers to compare works by Maurice Denis, Édouard Vuillard, and H.G. Ibels against images by Félix Vallotton, Félix Bracquemond, or Paul Helleu. This illuminating comparative installation gave considerable attention to the great range of the prints included in the portfolio and suggested reasons why Marx's enthusiasm for the artists, and their achievements, was so fervent. Alexandre Lunois, Edgar Chahine, Frank Brangwyn and Eugène Bejot, other lesser-known creators active around 1900, were hung in a subsidiary gallery, further suggesting the wide range of artists involved in the printmaking movement sponsored by L'Estampe Originale. In order to highlight Marx's fascination with prints, the organizers cleverly placed photographs of the interior of his home showing his personal exhibition of the prints that reinforced the focus of his art criticism (fig. 8). This very convincing aspect of a show that aspired to demonstrate just how deeply committed Marx was to all areas of the visual arts—even those not always considered as important as painting or sculpture—revealed that the graphic arts were central to his inclusive point of view (fig. 9). The only problem this reviewer can point to is the separation of the print section from the rest of the exhibition, most certainly due to the necessity of keeping the light in the galleries at a level suitable for the print medium. It might easily have been overlooked entirely by visitors, thereby vitiating one of the central tenets of the exhibition: Marx's dedication to prints in his writings. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The First Floor: The Early Years On the first floor of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, the exhibition quickly established who Marx was, and where he could be situated amidst his better known contemporaries. A plaster bust by Auguste Rodin referenced how the most dominant sculptor of the century visualized the art critic (fig. 10); the fact that the work remained at the plaster stage is not discussed, although a perceptive visitor might have wondered about the further implications of the relationship between the men, especially since Marx was such a dedicated advocate of all Rodin's symbolist work. Marx's books were also included in the installation, revealing how important his writings had become for others including his influential L'Art Social—a defining text on how art reflected the social conditions of its era. Importantly, the argument, made early on, was that Marx was not a creator himself, but rather a reflective commentator and a fervent champion of many artists at a time when their works were not always widely appreciated. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In the next section, "1882-1889: des Beaux-Arts à l'unité de l'art," Marx's interest in the applied arts emerged. His dedication to originality was objectified in works by Jules Chéret, vases by Emile Gallé and ceramics by Ernest Chaplet and Auguste Delaherche. The idea that historical styles should dominate creativity didn't hinder his thought process; instead he discovered what was unique in even the smallest object by individual creators (fig. 11). It is with this segment of the exhibition that Marx was shown to be much more than simply a chronicler of past accomplishments; he was opening art criticism to a more forceful probing of the decorative arts and the ways in which they could be enlisted to create a totally designed environment. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

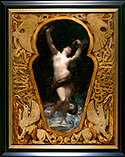

The period from 1890-1897 became a crucial one. Marx was fully committed to the avant-garde as it moved away from naturalistic renderings and pictures with a strong narrative content. He particularly advocated the Symbolist strivings of Odilon Redon, Auguste Rodin, Félicien Rops, and most importantly, Paul Gauguin. Thus, in a section closely associated with the other figures, Gauguin, and his influence, held sway. It was through Gauguin that Marx was able to see how ornamental design was infused with a deeper, personal meaning best found in the works of other artists included in the exhibition (fig. 12). Similarly, Marx became fully committed to a new way of interpreting landscape according to a Symbolist aesthetic, finding in the works of Claude Monet paintings that did not conform to any particular point of view aside from stressing personal moods. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Curiously, the critic was also interested in other painters who were not linked with the avant garde during this era. In referencing Alfred Roll, Jean-Charles Cazin or P.A.J. Dagnan-Bouveret, Marx was judged a notable independent voice, one that didn't hold the party line (fig. 13 and fig. 14). He found originality amidst those painters with a decidedly more conservative bent, placing the importance on the finished art work and its symbolic message, above any particular political inference or position that an artist might hold. In this regard, Marx's advocacy comes through passionately in the show; it reveals him as a devotée of diversity even though he was fervently interested in the progress of the avant garde. After leaving the first floor of the exhibition, visitors were confronted with a fuller range of Marx's interests reflective of the varied artistic approaches at work during the Third Republic, one that had as its main tenet the unification of the arts. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Second Floor: An Art for the People The second floor of the exhibition demonstrated Roger Marx's maturation as a perceptive writer and connoisseur. He believed that art should reach all the people, seeing that all objects—large or small—had to have two qualities: utility and beauty. A jewel box, designed by the progressive and controversial artist, Rupert Carabin, emphasized the ways in which sculpture and the applied arts could be united (fig. 15 and fig. 16). To Roger Marx there was no difference between areas of artistic production; he was simply looking for artists to express the raison d'être of an object in the most effective and artistically pleasing way. He wrote about metalwork, and medallions, supporting the creativity of Oscar Roty, for example (fig. 17). Since Marx was deeply committed to the beautification of French stamps, and to the designs used on the face and back of French bank-notes, objects of everyday use, he was interested in seeing that art was everywhere, and that the most mundane type of object was beautifully crafted. The exhibition makes this point absolutely clear, becoming in the process one of the first shows to demonstrate how art, ideology and practicality were melded during the Third Republic as many artists went to work for the government to make sure that controversial ideas were given visible form. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| As the exhibition progressed, considerable attention was given to the ways in which a new art, an art nouveau style, was united with art with a social message. In the period between 1898-1913, the admiration that Marx held for the work of Charles Plumet—an architect—or René Lalique—a jeweler—suggested that art could exist in many spheres and that there could be many aspects of society that could be touched by various creators (fig. 18 and fig. 19). Deeply involved with the Paris World's Fair of 1900, Marx saw that this was a moment when modernity was apparent and historical styles were in full retreat. No matter which artists were shown, Marx came to their aid in numerous articles in the press seeing that the works of Félix Vallotton, Henri-Gabriel Ibels, Paul-Élie Ranson and others were among those that needed to be enthusiastically applauded for their originality. One issue emerges: since Marx was a devotée of the art of 1890s, it was only upon occasion that, after 1900, he was able to acknowledge the merit and contribution of any given artist. However, he singled out Paul Cézanne as a creator of exceptional merit and originality—a position with considerable perspicacity at the time. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The complexity of the various artistic approaches of the time made it difficult for any one critic to be attuned to all the rapidly changing approaches. As a man of the nineteenth century, and as a figure deeply committed to the proposition that all the arts be united, Marx was seemingly less interested in the changes in painting that occurred after 1905. The exhibition bravely and quite successfully manages to deal with these issues, although it is often easier to address them in a catalogue than on the walls of an exhibition. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Toward Art as Total Decoration: The Musée de l'Ecole de Nancy As the catalogue for this exhibition makes amply apparent, Roger Marx was a faithful supporter of the art and culture of Nancy, his native city. From the moment of his early publication on "L'Art à Nancy en 1882," Marx selected a young group of creators with whom he kept in contact throughout his career and theirs. Whether it was with the painters Camille Martin (1861-1898) and Émile Friant (1863-1932) or the painter-decorator Victor Prouvé (1858-1943), Marx wrote about and collected their work (fig. 20). Many of these creators, along with the bookbinder René Wiener (1855-1939), became his closest friends—some of them because of their shared Jewish heritage. His interest in Émile Gallé, the fact that he collected a number of his works, and the relative ease with which he was able to write about this artist's work, came to an end only in 1904 when Gallé died. No matter the venue for publication, however, Marx remained his own man; he retained an independent voice even when some of the artists he wrote about became close friends. Since the show also gives space to the actual works that Marx collected by some of the artists he wrote about, it is clear that art and life were fully integrated in Marx's mind. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

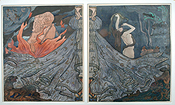

| One of the major aspects of this exhibition, aside from the full integration of the graphic arts, was the way in which the decorative arts—especially objects produced in Nancy—were given their own space at the Musée de l'École de Nancy. The intellectual reason behind the shift had to do with the fact that the Nancy artists remained true to the ways in which Marx valued them, and were entitled to their own galleries. Here, Prouvé's works dedicated to the theme of Salammbô were given considerable attention; this image, one of the most supreme of the Symbolist conceits emanating out of Gustave Flaubert's construction of a femme fatale, was remarkably vivid. The Salammbô book cover, based on watercolors by Prouvé (fig. 21, figs. 22-27, fig. 28, fig. 29, fig. 30), made the case eminently clear that Symbolism and Art Nouveau were combined in a region that had as its major advocate one of the most sensitive and insightful writers of the nineteenth century. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Contribution One of the sad commentaries about this exhibition is the fact that few people were able to see it. Hidden in the city of Nancy, open only during a few months in the summer of 2006, the exhibition traveled nowhere else. While the creation of an exhibition around the personality, collecting and writing of an art critic is an extremely complicated project to develop, this exhibition was one of the finest of its kind. It was supported by a highly readable and exceedingly well-researched catalogue, a publication that covered many of the themes that the writings of Roger Marx emphasized, and which will be the fundamental tool on this figure for years to come. This publication, however, has its limitations. Existing only in French, and without a distributor worldwide, the book is destined to go out of print rapidly and to be found only within specialized libraries. This is too bad for the various authors who worked so hard on the edition, and this is also sad for its subject. Roger Marx deserved a much wider exposure than the one he received in the exhibition and catalogue, especially since his entire career was dedicated toward bringing art to the people, and showing that all types of art should be accessible and understood. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The show and publication, which are largely based on the brilliant and intrepid research work of Catherine Meneux, are a testament to perseverance and insight. Roger Marx, who was a mysterious figure lost in time and the annals of art history, now steps forth as a full-fledged force in nineteenth-century critical thought associated with the early Third Republic. The fact that this has been accomplished in a carefully developed exhibition, where all the phases of Marx's varied interests were effectively visualized, is a remarkable achievement. The value of this show, highly abstract in terms of the issues raised, will long be remembered in Nancy and by the few outside visitors who had the chance to see it, to experience it, during the heat of the summer of 2006. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gabriel P. Weisberg University of Minnesota |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1. In a recent e-mail exchange with Professor Michael Mendle, of the University of Alabama, he has noted that in the exhibition catalogue of the Japanese print show at the École des Beaux-Arts (1890), where S. Bing was the primary organizer, he discovered an inscription from Bing to Marx (in the exhibition catalogue for the show which he obtained from Louisiana State University) that was warm and exceedingly friendly. This should come as no surprise since Bing and Marx must have been very close colleagues. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||