The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

Painting and Memory in the Career of Édouard Vuillard |

||||||

|

Édouard Vuillard National Gallery of Art, Washington 19 January – 20 April 2003 The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts 15 May – 24 August 2003 Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris 23 September 2003 – 4 January 2004 Royal Academy of Arts, London 31 January – 18 April 2004 Guy Cogeval, et al. |

|||||

|

The retrospective exhibition of Édouard Vuillard on view at the National Gallery in Washington between January and April of this year marked a watershed moment for Vuillard scholarship and won a sizeable audience for his subtle and seductive work. The scope of the exhibition approached that of a modern-day blockbuster; containing over three hundred paintings, drawings, prints, and photographs, it amounted to the largest exhibition of Vuillard's work to date. After its Washington début, the show continued on to the other three contributing institutions, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Réunion des musées nationaux/Musée d'Orsay, Paris, and the Royal Academy of Arts, London. | |||||

| The mastermind behind the show was Guy Cogeval, Director of The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, whose publications on Vuillard date back to the late 1980s.1 Cogeval's work on this artist culminates in the current retrospective and accompanying 500-page catalogue with contributions from Kimberly Jones, Laurence des Cars, MaryAnne Stevens, Dario Gamboni, Elizabeth Easton, and Mathias Chivot. The catalogue consists of both scholarly essays and essential documentation, including a virtual encyclopedia of lavish color illustrations, provenance and exhibition history of the 334 works shown at the four locations, a detailed chronology, and a full bibliography of the secondary literature. The exhibition and catalogue have been timed to coincide with the forthcoming and long-anticipated catalogue raisonné of Vuillard's paintings and pastels co-authored by Cogeval and Antoine Salomon.2 Behind this two-pronged effort lie years of research into the artist's hitherto unstudied private records owned by Antoine Salomon, the artist's heir. The Vuillard retrospective is thus part of a landmark effort to crack open Vuillard's private world and present it in extraordinary scope and detail to the public. | ||||||

| Despite the gigantic size of the exhibition, the feeling at the National Gallery when I visited it was not one of mass spectacle. How could it be, given Vuillard's notoriously shy and reclusive character? Visitors circulated quietly as if unwilling to disturb the paintings' mood of reverie. No doubt the muted gray-green walls and soft lighting contributed to this atmosphere, yet the contemplative tone was set by the works above all, which speak in whispered voices to those willing to come closer and listen. The retrospective featured Vuillard's small easel paintings, theater designs, domestic decorations, photographs, and portraits— bodies of work which have often been treated separately if at all in the secondary literature and previous exhibitions.3 The installation proceeded chronologically through nine rooms, beginning with Vuillard's student years, whose experiments culminate in his breathtakingly beautiful Symbolist paintings of the early and mid 1890s. The show continued with two rooms devoted to landscapes and photographs, and ended with three rooms full of Vuillard's elegiac portraits from the decades between 1910 and 1940. | ||||||

| The emphasis of the exhibit was on painting, and this decision was no doubt informed by Cogeval's focus in preparing the catalogue raisonné. However understandable given the richness of the material, the privileging of painting reinscribes the artist's career into the very Beaux-Arts hierarchies against which he revolted, particularly in the 1890s. Under-represented was Vuillard's serious interest in the applied arts, in particular prints. Though Vuillard's lithographed theater programs were included in the show, they appeared only within the context of his involvement between 1891 and 1896 with Lugné-Poë's avant-garde stage, the Théâtre de l'Oeuvre. Absent from the 2003 retrospective was a fuller account of the artist's sustained interest in the graphic arts. Vuillard created sixty lithographs between 1893 and 1935, and only eleven of these were related to dramatic performances.4 A more complete showing would have revealed that Vuillard's prints were intimately related to his painterly experiments. Designed to be viewed by individuals at home, the artist's graphic work lends another dimension to themes of domesticity and interiority articulated in his paintings from the same period. Looking more closely at Vuillard's lithographs, including an 1894 commercial poster for an aperitif Bécane, would have also provided an opportunity to consider how the interior as conceived by Vuillard was not the hermetically sealed chamber it has so often been made out to be. Vuillard's experimentation with lithography, a medium designed for mass reproduction, suggests that he was also interested in exploring art's potential to address a popular audience. | ||||||

| Questions of Vuillard's engagement with the applied arts were also inadequately addressed in the exhibit's presentation of Vuillard's magnificent decorative wall panels, Jardins Publics (1894) and Album (1895), which depict women and children in enclosed environments. Commissioned by Alexandre Natanson, manager of the advanced literary and artistic periodical La Revue blanche, and his brother Thadée, who served as the review's editor, these large-scale works were conceived as permanent decorations for private apartments. The comprehensive scope of the Washington show meant that it brought Vuillard's small- and large-scale paintings into dialogue—a dialogue which seldom occurs in specialized or thematic exhibitions. As such, the retrospective provided an opportunity to re-examine the commonplace view that Vuillard's small-scale works are intellectually and artistically sophisticated whereas his large-scale domestic mural decorations are nothing but pretty wallpaper.5 | ||||||

| Though Cogeval and the exhibition organizers must be heartily commended for reuniting the various panels of Vuillard's decorations and bringing them to Washington, the curators did not make the case for the panels' role in Vuillard's Symbolist experiments forcefully enough. The retrospective featured eight of the nine panels of Vuillard's 1894 Jardins Publics and four of the five panels of his Album series (1895). These paintings impress the viewer by their sheer scale: each of Jardins Publics' canvases measures over 2 meters tall and varies between 68 and 154 centimeters wide (Fig. 1). Though the immediate visual impact of these decorative series was undeniable, they were not shown to their full advantage. Nothing in the Washington installation signaled to the viewer that these paintings trace themes of domestic and psychological interiority present in Vuillard's small-scale canvases. That Jardins Publics and Album's private orientation was misunderstood by even experienced viewers can be seen in Michael Kimmelman's review for the New York Times, in which he writes: "The show argues for the seriousness of these decorative ensembles. This case has been made before. It still seems a stretch. These are public projects. Vuillard's gift was for private, keyhole views, intense, oddly cropped and voyeuristic, which seem to speak a secret language, like a joke between friends and lovers."6 Such misunderstandings might have been avoided by indicating the original domestic installation of the panels. One way of doing this would have been to have papered the appropriate room with ornately patterned turn-of-the-century wallpaper as Gloria Groom did so successfully two years ago in Beyond the Easel, an exhibit devoted to Nabi decoration.7 This kind of installation would have helped viewers see that Vuillard's domestic decorations are linked to his Symbolist paintings in the equation they set up between domestic interiors and psychological interiority. Painted as permanent decorations for private apartments, Jardins Publics and Album were meant to be lived with rather than visited. As such, Vuillard's decorations demand a special kind of attention; they speak to viewers indirectly, addressing the viewers' unconscious faculties into which they work their way slowly, over protracted periods of time. | ||||||

| So dominant was the chronological presentation of Vuillard's painting that it proved difficult to integrate other media in a manner which made sense. This was seen most vividly in the case of Vuillard's photographs which figured for the first time in a retrospective of his works. An entire room was given over to the snapshots which the artist produced of himself and his friends from 1897 on, and which were meant as studies for his later paintings. (This selection only scratches the surface of the 1750 images preserved in the family collection.) The subsidiary role of Vuillard's photographs, however, did not come across in their installation. The photos appeared in a separate room, which suggested that they were meant to be viewed as independent works of art. A far more effective, if didactic, installation would have placed photographs alongside individual portraits for which they served as studies. Such comparisons figure in the exhibition catalogue and one wonders why they did not inform the exhibition design. | ||||||

| Pairing photographs with paintings would have indicated more clearly the extent to which the photographs were inextricably tied to Vuillard's evolution around 1900 towards more objective, naturalist procedures. Instead, the photographs were presented in the exhibition as "transitional" works in the sense that they continued the domestic subject matter and oblique viewpoints of Vuillard's earlier painting, but grounded this subject matter more firmly in the data of sensory experience.8 In attempting to link Vuillard's photographs to his earlier painting, however, the exhibition organizers smooth over important differences between these two bodies of work. Transition implies continuity, and the exhibition doesn't emphasize enough how the photographs constitute a break with Vuillard's previous, Symbolist practice. Vuillard's 1890s paintings were deliberately anti-photographic in their poetic and suggestive distortions. In them, the artist didn't record individual sensations so much as filter them through the subjective faculties of imagination and memory. | ||||||

| A Career of Painting the Bourgeoisie The attempt to relate the early and late phases of Vuillard's career through the installation of Vuillard's photographs spoke to a larger ambition on the part of Cogeval and his collaborators. Underlying the show was an argument for thematic continuity between Vuillard's nineteenth- and twentieth-century paintings. Cogeval accomplished this in the exhibit's installation by striking a balance between Vuillard's Symbolist and post-Symbolist paintings. This resulted in the showing of an unprecedented number of Vuillard's late portraits, and marked a departure from previous landmark retrospectives by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie and John Russell, which emphasized the artist's Symbolist work.9 Ritchie and Russell make a strong case for Vuillard's 1890s work in their respective catalogue essays, where they argue that Vuillard's art, which had always been strongly affected by his emotional and intellectual relationships, suffered with the dissolution around 1900 of Symbolist groups and institutions, including the Nabis, the Théâtre de l'Oeuvre, and the writers, artists, and musicians contributing to La Revue blanche. The artist went on after 1900 to find a new source of support in the more conservative and staid art dealers Jos and Lucy Hessel, who were connected to the Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, but these new patrons did not provide the same intellectual or artistic challenges. Two driving forces dominated Vuillard's life: the need to paint and the desire for social acceptance. These two aspirations reinforced each other in the 1890s when the close friendships Vuillard enjoyed with members of the Nabi brotherhood fueled and sustained his path-breaking formal innovation. The same reliance on his immediate social circle proved detrimental to Vuillard's art after 1900, according to Ritchie and Russell. In part because of the Hessels' and Galerie Bernheim-Jeune's taste for Impressionism, which by 1900 had become widely accepted and whitewashed of all its radical associations, Vuillard's work in the twentieth century became less ambitious, more cautious.10 |

||||||

| Cogeval argues against Ritchie's and Russell's interpretations by downplaying the ostensible break which occurs in Vuillard's career at the end of the Symbolist period and by arguing for continuity between the 1890s paintings and those created after 1900 on grounds of irony and narrative. In his 2003 essay and in previous scholarship, Cogeval reads Vuillard's Symbolist canvases in the context of the artist's participation in Lugné-Poë's Théâtre de l'Oeuvre. In the 1890s, Vuillard had helped stage performances of plays by Ibsen and Maeterlinck, which exposed the contradictions and psychological anxieties underlying bourgeois existence.11 Cogeval sees similar criticisms at work in Vuillard's twentieth-century portraits, which he characterizes as "varnished with vitriol."12 Cogeval writes: "His late portraits demonstrate the three constants of his declining years: his enthusiasm for spotting the flaws in contemporary society, an irony that was sometimes quite destructive, and a certain wisdom—the fruit of advancing age."13 | ||||||

| Cogeval's emphasis on irony stems from his understanding of Vuillard's engagement with Symbolist theater as well as details of the artist's private life revealed in his hitherto unstudied correspondence. In his catalogue essay, Cogeval brings to light new information from Vuillard's private letters which have previously been closed to researchers. He fills out our picture of the relationships between Vuillard's family circle composed of his mother, sister Marie, and his brother-in-law, closest friend, and painter, Ker-Xavier Roussel—individuals featured time and again in Vuillard's paintings such as Interior, Mother and Sister of the Artist (1893) and Interior with Worktable (The Suitor), (1893). These relationships, which alternated between tenderly loving and sadistically destructive, are fascinating and Cogeval's account puts an end to decades of speculation on the part of scholars about the nature of Vuillard's familial relationships. | ||||||

| While Cogeval's catalogue essay represents an original contribution to Vuillard scholarship, his focus on narrative makes him less attentive to questions of medium and idiom, and it is here that his argument for the continuity between Vuillard's Symbolist and post-Symbolist canvases appears most dubious. Cogeval forges unity within Vuillard's career by de-emphasizing the formal innovation of Vuillard's Symbolist painting. By relating Vuillard's 1890s painting to his twentieth-century portraits rather than to his earlier experiments with other media, Cogeval downplays the relationship between Symbolism, the decorative, and abstraction. Missing from this show is a sense of Vuillard's relevance to modernism with which his early work was intimately connected. One would hardly know from the Vuillard retrospective that the artist originates what would become a prolonged and serious investigation on the part of subsequent artists into notions of the decorative, intimacy and the unconscious as paths to modern, spiritual forms of painting. (Henri Matisse and Mark Rothko are two examples of artists who continued Vuillard's preoccupations, taking them in new directions.) By downplaying the significance of the decorative and giving so much weight to the artist's twentieth-century works, Cogeval and the exhibition organizers make Vuillard seem to be an essentially backward looking artist.14 | ||||||

|

Painting and Irony That unbridgeable stylistic, technical, and compositional differences separate Vuillard's 1890s paintings from those created after 1900 can be illustrated through a closer analysis of selected works in the exhibition. The show opens with the artist's stunning Self-Portrait with Waroquy (1889) (Fig. 2), a well-chosen painting which effectively sets up the main aesthetic tension that structures Vuillard's career: the relationship between an attentiveness to nature and its distortion to represent subjective experience. This sensitive and disarming self-portrait consists of equal parts brilliant illusionism which lends it concreteness and immediacy, and confounding obfuscation, which demands a more indirect, subjective reading. As a result the mimetic procedures of painting are disrupted. This portrait, which marks Vuillard's turning away from naturalist procedures of visual recording towards a more allusive mode of expression, amounts to an act of self-reflection upon artistic identity and painterly language. The rounded bottle and its flattened reflection in the lower right corner indicate that what we are looking at is a mirror image. However, Vuillard stages doubling in order to undermine it. Traditional illusionism can be found in certain areas—in the sophisticated play of light on the rounded bottle's surface, in the superb foreshortening of the artist's palette, and in the vivid modeling of the artist's left hand, which marks the brightest and most tangible point of the canvas. These painterly effects coexist with a flattening of space that shores up image's artifice. Take the figures out of the picture and the space appears perfectly two-dimensional. Since Vuillard's and Waroquy's contours are not well-established, dissolving as they do into the background rather than standing out against it, their figures hover in a liminal state between presence and absence. This is particularly the case in the areas where Vuillard's dark jacket seems to fade into the pools of brown and black behind it. The duality between presence and absence can also be found in the artist's rendering of his own face. He looks straight out to the viewer without affect or self-importance. And yet this directness is contradicted by uneven lighting, which casts his right eye in shadow and makes the artist appear less physically substantial, more emotionally distant. This distancing effect becomes more obvious in the other male figure, identified by the title only as Waroquy and presumably a friend of the artist, who appears as his paler shadow. If Waroquy's head appears insubstantial— it is only after protracted viewing that one notices the glowing ember of a cigarette jutting out of his mouth— his body is almost non-existent. In a startling act of negation, Vuillard has brushed grey-green paint over Waroquy's body, blotting it out. In certain areas the brush bristles have removed the underlying coat of paint to reveal the bare canvas. Though we can speculate that such effects may have originated in light reflections or surface imperfections in the mirror, the result is the figure's dematerialization. Rather than affirming the solidity of objects in the world and our ability to know them, Vuillard, in his Self Portrait with Waroquy, figures the fluctuating, imprecise nature of vision and any attempt to recall it through painting and memory. This negotiation of a new relationship between sensation and imagination will become the mainstay of Vuillard's visual language. |

|||||

| Self-Portrait with Waroquy indicates the ways in which Vuillard called into question naturalist procedures of visual recording, which had marked artists of his generation. Vuillard's impatience with mimetic procedures is what led him to embrace Symbolist aesthetic theories which he encountered in discussion with fellow student-artists, Paul Sérusier, Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, Paul Ranson, and Henri Ibels. These young men formed the Nabi brotherhood between 1888 and 1889, a group of self-selected artists devoted to spirituality in art and experimentation with diverse media. Nabi or Symbolist artists redefined Impressionist notions of sensation based in retinal experience to include the invisible world of ideas and emotions. However, this new recognition of the spiritual alongside the material was not without its problems. The challenge Symbolism posed for painters was how to make invisible mental processes physically present, how to lend spiritual experiences physical embodiment through a concrete method of painting. In moments of frustration, Symbolism appeared to Vuillard as nothing but a disembodied theory of art-making that left the artist rudderless, aimlessly floating on the sea of his own imagination. This sense of indeterminacy can be seen in the first two rooms of the exhibition which show Vuillard searching for a solution among the available avant-garde idioms: we see him experimenting in abrupt starts and stops with the divisionist theories of Seurat's and Signac's Neo-Impressionism, the large pools of flat color characteristic of Gauguin's and Emile Bernard's Cloisonnism; Japoniste stylizations; and drawings and paintings that have the awkwardness and naiveté of children's picture book illustrations. | ||||||

| In addition to the painting of his immediate predecessors, Vuillard turned to Symbolist drama for inspiration and guidance, particularly that of Henrik Ibsen and Maurice Maeterlinck, for which he designed numerous sets and programs on view in the exhibition. Elements of Symbolist theater also crop up in his painting. The intense dramatic effects of Ibsen's Rosmersholm or Maeterlinck's L'Intruse can be found in Vuillard's Dinnertime (1889), in which a motley and threatening cast of characters—including one in a hooded black cloak and another wielding a large club—assemble for dinner. The shadowy props, including a bottle of wine and two candles, could as well serve as the setting for a cultist ritual. This painting is deeply indebted to dramatic performances at Lugné-Poë's Théâtre de l'Oeuvre in its utter stillness, dark lighting, and faceless anonymity. | ||||||

|

Symbolism at its worst amounts to an attempt to translate literature into painting (the Pre-Raphaelites succumbed to this allegorical mode, as did Arnold Böcklin); the strength of Vuillard's work is that it refuses to do this. The years 1891 to 1895 see him establishing his independence from Symbolist drama and laying the basis of a purely pictorial Symbolist idiom. In his canvases from these years, Vuillard's signature sense of strangeness and dislocation derives less from narrative than it does from the spatial ambiguities of his compositions (Fig. 3). Formal flattening and spatial compression can be seen in Interior (Marie leaning over her work) (1892-93), in which Vuillard simplifies form into flattened color without sacrificing pictorial structure or complexity. The greens, reds, blues, and yellows are perfectly calibrated—their brightness balanced against the warm browns of the chairs, dresser, and tables— and the brushstrokes are riveting in their intricacy, variety, and texture. This painting reveals that Vuillard has acquired a miniaturist's discipline, or rather that he has imposed one on himself in his conscious choice of a small surface (the cardboard support measures only 23 x 34 centimeters). This self-imposed constraint results in a precision not found in his previous works. The application of paint is varied; decorative dots, short swirls, and squiggles interact with broad, even expanses to create a lively surface. This focus on two-dimensional decoration, in which line and color are treated expressively, takes precedence over matters of physiognomy, narrative, and gesture. One cannot help but think of Maurice Denis's Symbolist credo: "A picture, before being a horse or a battle, a nude woman or some kind of anecdote—consists of a flat surface covered with colors arranged for a certain effect." And yet the figure remains for Vuillard all-important. The woman occupies the center foreground of the painting. The triangle created by her body bent over her work anchors and organizes the composition. However, Vuillard focuses on the figure only to redefine its significance, for the woman shuts down all narrative content. The woman turns her ashen face and tensely drawn shoulders away from the viewer in what seems to be an active avoidance of his presence. This is pure Vuillard, where physical intimacy is shot through with anxiety and the need for psychological distance. | |||||

| There is irony here, but it is more equivocal than Cogeval suggests. Although Vuillard contributed to performances of Ibsen's plays in the 1890s at Lugné-Poë's Théâtre de l'Oeuvre, his painted domestic scenes lack Ibsen's solid plotting and demonstrative rhetoric; their message is not emphatically declared but elliptically whispered. The Symbolist poet and theorist Albert Aurier struck the right balance between irony and enjoyment in his sensitive and insightful 1892 reading of Vuillard's work. Aurier's criticism—the first lengthy discussion of Vuillard— is noteworthy for its profound ambivalence, its characterization of the paintings as teetering on a razor's edge between harmony and dissonance, pleasure and foreboding. Aurier characterizes Vuillard as "an unusual colorist full of charm and the unexpected, a poet who knows how to convey, not without a certain irony, life's sweet emotions, tendernesses and intimacies." Vuillard appears in Aurier's characterization not as caustic critic but as one who insinuates doubt indirectly. | ||||||

| Aurier's description was motivated by Vuillard's small-scale canvases such as In the Lamplight (1892), in which irony is expressed above all through formal distortions which both seduce the viewer in their sheer painterly brilliance and alienate him in their imposition of psychological distance. The glow of gas light in this work is uneven, creating an unnatural pallor on the face of the younger woman at left and casting her back in shadow. Rather than revealing the solidity of objects and the stability of bourgeois life, light is used here to reveal it as shot through with unspoken tensions. And yet the most compelling aspect of In the Lamplight lies not in its subject but in its means of conveying it. The dancing tongues of black paint against the red wall are as expressive as the figures themselves. The comparison is irresistible, for the women's bodies have been flattened into black abstract patterns. The women shut down all narrative in their hidden faces, their mute gestures, and their self-isolating absorption. | ||||||

|

Intimate Decoration and the Collapse of Ironic Distance A similar mixture of sensual gratification and psychological tension structures Vuillard's masterful decorative series, Jardins Publics (Fig. 4). It is nothing short of a triumph to have assembled eight of this series of nine panels and two over-doors commissioned by Alexandre Natanson, director of La Revue blanche. Painted to decorate Natanson's sumptuous private apartment near the Bois de Boulogne, this work has not been publicly exhibited in its entirety since 1906. Though its format departs dramatically from Vuillard's small-scale Symbolist works, Jardins Publics continues the earlier paintings' feminine, interior focus. Nature has been thoroughly domesticated in these Parisian parks, which resemble living rooms in their high level of order and maintenance. Vuillard depicts sheltering spaces bounded on all sides by vegetation and even exaggerates the sense of confinement through spatial constriction. Furthering the sense of enclosure is the self-referencing between panels. The series can be divided into four groups of canvases, each of which constitutes a discrete spatial setting: Young Girls Playing and The Questioning; The Nursemaids, The Conversation, and The Red Parasol; The Promenade and First Steps; and The Two School Boys and Under the Trees. These four groups corresponded to the four walls of the Natansons' expansive living and dining room. In conceiving of such an arrangement (there is every indication that the artist was given free hand in both the panels' conception and execution), Vuillard expresses the wish to have interiors become microcosms of the outside world, for he has brought the lush setting of a park inside. However, the traditional relationship between interior and exterior has been inverted: rather than employing techniques of perspective and illusionism according to which a painted landscape becomes a window giving out onto nature, Vuillard employs emphatic horizontals, compressed space, and unblended brushstrokes to articulate painting as an impenetrable, material barrier which entraps nature. |

|||||

|

Not only the setting and the installation, but also the subject matter and overall mood of Jardins publics is introverted. For the most part, the women and children face away from the viewer. Indeed, his women seem to have barely left their homes —they are covered from head to toe in clothing whose ornate patterns recall wallpaper. They huddle together on park benches, as if afraid of the sandy floor; one woman in Conversation (Fig. 5)hides behind her parasol as if trying to recreate a sheltered, interior space outdoors. There are, of course, children playing—jumping, spinning, and running. Their exuberant, spontaneous movements recall the children's games animating Bonnard's garden paintings; Vuillard even quotes Bonnard's signature lap dog in The Red Parasol (1894). But Vuillard's children appear more distant and artificial than Bonnard's in their faceless anonymity. The leaping girl in The Questioning epitomizes the strange mood of these canvases in her anatomical impossibility; her body faces us, but her head is turned backwards so that we do not see any of her physiognomy; her feet are unattached to her body. The girl has raised her hands as if to propel a twist in mid air, but rather than suggesting movement, her exertions have been artificially frozen. Instead of turning in space, she appears to be pressing against the surface of the canvas. She appears trapped, a figure of mute suffering. Of course this is only one moment in an otherwise balanced and pleasing composition bounded by sun-speckled sand and blossoming chestnut trees, but its weirdness is undeniable. Underlying such disturbing moments is doubt concerning the expressive role of figures and the inevitable tensions which result from the attempt to flatten them into decorative arabesques. | |||||

| Despite the Jardin's oddities, I disagree with Cogeval's interpretation that the series is tinged with morbid premonition.15 Drawing on information contained in Vuillard's letters, Cogeval interprets the swaddling engulfing the baby in Jardins Publics: The Conversation as a death shroud and sees this uncanny resemblance as foreshadowing the loss of Vuillard's nephew's in 1896. Not only is this reading historically unlikely; Cogeval's interpretation is contradicted by Vuillard's idiom itself, which shuts down the possibility of ironic distance. Site-specific panels had the potential not just to represent a domestic or park interior, but to become part of the familial environment where they were also capable of inducing in the viewer a state of interiority or introspection. Vuillard's Symbolist paintings, and especially his Symbolist decorations, propose a new aesthetic of suggestion, in which narrative and illusionism give way to rhythmic repetition of line and color. Rather than serving a moral or didactic purpose, the painting's expressive colors and repetitive rhythms are designed to have a quasi-hypnotic effect on the viewer, lulling his faculty of reason to sleep and awakening sympathetic internal vibrations.16 This is a prefiguration of Matisse's armchair painting, which is not looked at directly but which surrounds the viewer, forming the backdrop of his daily existence. The purpose of such an aesthetic of suggestion is to break down the barriers between viewer and painting, subject and object, through carefully orchestrated rhythmic resonances. | ||||||

| Everything that we read about Vuillard's work on this decorative series, which is uncommonly well-documented in his journal, suggests that the artist understood decoration as a means of overcoming gloomy fantasies, of tempering the intellectual and psychological pressures of Symbolist subjective creation. Decoration appealed to Vuillard because he saw in it a way to anchor an extremely individualist mode of painting in artisanal craft and repeatable method. The inspiration for Jardins Publics had occurred during his 1894 visit to the Musée de Cluny where he studied the exhibit of medieval tapestries. Tapestries not only provided direction for his work, however; they also allowed him to see a continuity between his small panels and his larger, commissioned works. Vuillard was particularly pleased upon viewing tapestries to note that he had developed his own decorative aesthetic parallel to, yet independent from, the work of previous ages. What comfort to find that his painting, which had previously seemed to him too individualist, lacking in stable, repeatable method, could find sympathetic resonance in a pre-modern, collective, tapestry tradition. | ||||||

| This "discovery" of tapestries allowed Vuillard to conceive of Symbolist decoration as composed of two parts: one based in a radical, and essentially modern, subjectivism such as the one he had elaborated in the first years of the 1890s; and another consisting of what he perceived as artisanal, physical labor, essentially non-intellectual, and in step with medieval tradition. This dialectic between subjective and objective procedures structures Jardins publics. On the one hand there is the strange compression of the figures in The Questioning; spatial flattening can also be found in The Two School Boys and Under the Trees, in which the perspectival depth achieved in the lower halves through reductions in scale disappears in the upper registers' dense friezes of foliage. These distortions recall those structuring Vuillard's small-scale Symbolist canvases. | ||||||

| On the other hand, Vuillard in Jardins Publics arrives at a new form of painterly discipline. Though the artist breaks with the rules of perspective in the series, he arrives at a new means of unifying the composition in the form of individual, unblended touches of paint which recall the seemingly mechanical procedures of tapestry-making. The foliage consists of small specks which suggest pointillism minus its underlying principles of color divisionism. In their discreteness and uniformity the dots differ from the heterogeneous mixture of brushstrokes characteristic of Vuillard's earlier canvases such as Interior (Marie Leaning Over Her Work). Rather than varying his brushstrokes in Jardins Publics, Vuillard layers individual daubs on top of each other to create a rich tapestry of texture and color. Long, twig-like branches criss-cross the surface to lead the eye across the composition. Similar effects can be found in his sandy ground, which is also composed of small, uniform touches of color. The texture of the sand, its colored reflections, and the play of light and shadow are a source of endless fascination. The pink, taupe, and blues of his sand evoke the expressivity and nuance of Redon's Flower Clouds. The colors of Vuillard's sand are as delicately and intricately layered as those in Monet's Water Lillies, though of course their effect is more matte and subdued, less explosive. The restraint expressed in both Vuillard's palette and methodical touches signals a certain austerity, and the pleasures afforded by Jardins Publics are less accessible, more cerebral than Monet's showy late works. Like the paintings by Puvis de Chavannes, the fascination of these decorations turns on the tension between a lush outdoor environment and its isolated and impassive inhabitants, who remain physically and emotionally inscrutable. | ||||||

| Vuillard's Late Work: Painting as Elegy What becomes of this tension between objective and subjective modes of painting in Vuillard's late works? What kinds of relationships can be drawn between his early Symbolist interiors and his portraits of private individuals painted after the dissolution of Symbolism circa 1900? Cogeval is understandably interested in Vuillard's late works, which are fascinating and complex documents. However, he goes too far in his attempt to rehabilitate them in claiming that Vuillard's portraits sustain the innovation and excitement of Vuillard's Symbolist paintings. The argument for continuity between Vuillard's early and late careers is a difficult one to make. Though technically accomplished and often poignantly expressive, Vuillard's art after 1900 foregoes the startling obscurities and intriguing distortions of his Symbolist canvases in favor of an effort to reproduce natural appearances. Or we should rather say that he returns to this more material mode of painting, for Vuillard's earliest works were marked by faithfulness to outward forms. One only has to look at his charcoal study Self-Portrait (1887-1888) with its mournfully expressive eyes to realize how the young Vuillard, aged twenty, excelled at the art of physiognomy. Vuillard never entirely rejected an attentiveness to the natural world; his best works from the 1890s are marked by a tension between the cultivation of one's sensations and their distortion to express underlying emotions or ideas. This tension disappeared after 1900 once Symbolism as a movement was largely spent. |

||||||

| Vuillard's late portraits share with his Symbolist paintings a common subject matter— figures in interiors— and in this sense his subject matter remains consistent throughout his career. But Vuillard's mode of painting changes. Portraiture is the most traditional of genres and serves a largely social function of presenting public or private figures to an audience less familiar with them. While created for specific individuals, portraits also function as commodities which can be readily bought and sold. As such, portraiture marks a break with Vuillard's earlier site-specific decorations, in which he had deliberately eluded traditional genres, formats, and institutions. | ||||||

|

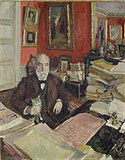

Portraiture's specific purpose inflects Vuillard's compositional and stylistic decisions. The late canvases adhere to conventions of narrative according to which each object or figure in the painting, in addition to playing a compositional role, illustrates a facet of the sitter's character and achievement. Take Vuillard's Portrait of Théodore Duret (1912) (Fig. 6), which could easily be considered his most accomplished portrait. We see the critic and historian of Impressionism in his office surrounded by his papers, books, and art collection— records of his past achievements. On the back walls, alongside Ingres's sketch for The Muse of Lyric Poetry (c. 1842) and Gustave Moreau's Orpheus, can be recognized Whistler's Arrangement in Flesh Colour and Black: Portrait of Théodore Duret (1883-84) seen, significantly, in the mirror. Here we find an equation between painting and mirroring, and yet mirroring here functions as a nostalgic looking back—to the audacity of one's youth, to intellectual and worldly success. Laurence des Cars has described this portrait as "a marvelous echo of Duret's brilliant youth, when he dictated contemporary taste with the elegance— in Manet's words— of 'the last of the dandies.'"17 The contrast between Whistler's dapper Duret and Vuillard's more doleful portrait is only too poignant. Duret leans back in his chair lost in introspection. We see him as a bleary-eyed critic then in his seventies No writing instruments are visible on the desk, from where he surveys his work from a position of emotional and physical detachment. Instead of a pen, he clutches a cat, who seems to provide an element of comfort or solace to an otherwise bathetic moment. Despite the melancholic tone of this portrait, I see sympathy, even empathy, rather than ironic distance, for the parallels between Duret's and Vuillard's careers are only too apparent. | |||||

| Even if we admit the critical nature of Vuillard's late portraits for which Cogeval argues (and this reading is difficult to secure, so much do his late pictures vary in tone and temperament) is this enough to assure their artistic ambition? Though Vuillard's portraits might contain moral ambiguity in which shades of contradictory characters are developed, there is never painterly ambiguity, and it is here that Vuillard's painting demonstrates a slackening of ambition, if not of skill or complexity, in relationship to its historical moment. Vuillard's late paintings are moving testaments to an individual's search for artistic and social stability which he found, respectively, in naturalism and in high society. It is impossible not to see Edmond Duranty's Realism in his portraits of bourgeois collectors and grandes dames, "the study of moral character as it is reflected in physiognomy and dress, the observation of man's intimate relationship to his apartment, of the special mark impressed on him by his profession."18 Vuillard's portraits of Countess Marie-Blanche de Polignac (1928-1932) and of Jeanne Lanvin (1933) are full of sensitive and profound insights into worldly ambition and human frailty in their juxtaposition of sumptuous and impressive interiors and their weary and aging inhabitants, but these observations are expressed in what had become an essentially conservative idiom. In these late works Vuillard bids his adieu to avant-garde innovation, preferring to paint within the familiar forms and rhetoric of nineteenth-century Realism. | ||||||

| The difference between Vuillard's Symbolist and post-Symbolist works can be summed up in his different treatments of memory. Painting from memory in the early years of Vuillard's career enabled him the imaginative distance necessary for forging a new idiom; as such painting from memory was synonymous with anti-naturalism and rule-breaking. As Vuillard grew older, memory became less allied to innovation and more to the task of preservation—preservation of the world of his haut-bourgeois and noble clients which, in the years surrounding World War I, was on the brink of disappearing. It is to Vuillard's attempt to capture and document the lives of the late-nineteenth-century elite in all their intricacy and detail that his photographs and portraits speak most movingly. Vuillard's historical consciousness of his subject matter's fragility may, in part, account for these paintings' occasional mood of mourning and melancholy. However Vuillard's late works signal more than the end of an historical period: in their alternation between critique and elegy, they constitute a swan song to a nineteenth-century painterly tradition grounded in the contradictions and seductions of bourgeois experience. | ||||||

|

And yet, Vuillard's art was not only backward looking; at the heart of his best works lie some of modernism's persistent questions. There is one portrait which sustains some of the doubt and ambiguity that is so seductive and fascinating in the artist's early self-portraits and Symbolist canvases. Self-Portrait in the Dressing Room Mirror (1923-24) (Fig. 7) depicts the artist as a Homeric poet who stares blindly into the mirror. In the place of eyes he has bored two dark circles. Vuillard's negation of the artist's vision suggests that the golden, glowing scene must result from memory or imagination. Self-Portrait in the Dressing Room Mirror allows us to pinpoint what about Vuillard's best work is so riveting. It is not its narrative, its ironic staging of tense familial dramas à la Maeterlinck or Ibsen. Rather its fascination lies in its medium itself or, more specifically, in Vuillard's manipulation of the medium to insinuate doubt into our perceptions and their representation in painting. | |||||

| Katherine M. Kuenzli Assistant Professor of Art History Wesleyan University |

||||||

|

1. Among the most important writings of Cogeval are Les années post-impressionistes (Paris: Nouvelles Éditions Françaises, 1986); "Le célibataire mis à nu par son theater, même," in Vuillard, eds. Anne Dumas and Guy Cogeval (Paris: Flammarion, 1990), 105-135; Vuillard. Le temps détourné. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux/ Gallimard "Découvertes," 1993); Il tempo dei Nabis, (Florence: Palazzo Corsini/Artificio), 1998; The Time of the Nabis, ( Montreal: The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1998); and Vuillard: Post-Impressionist Master (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2002, a new version, in English, of his 1993 study. 2. Guy Cogeval and Antoine Salomon, Vuillard: Critical Catalogue of Paintings and Pastels (Paris: Wildenstein/Milan:Skira, 2003) 3. Precedent for Cogeval's approach can be found biographies or monographic studies and exhibitions of the artist. See André Chastel, Vuillard. 1868-1940 (Paris: Floury, 1946); Claude Roger-Marx, Vuillard et son temps (Paris: Editions Arts et métiers graphiques, 1946); Jacques Salomon, Vuillard, témoignange (Paris: Albin Michel, 1945); Belinda Thomsom, Vuillard (Oxford: Phaidon, 1988); No retrospective has covered Vuillard's easel paintings, prints, decorative panels, drawings, and photographs in such a comprehensive manner. The 2003 retrospective is the first one to treat Vuillard's photographs at all. For a complete listing of Vuillard exhibitions, see Cogeval et al., Édouard Vuillard (2003), 484-486. By far the largest number of books and exhibitions on Vuillard have treated his work from the 1890s within the context of the Nabi brotherhood. See Patricia Eckert Boyer, Artists and the Avant-Garde Theater in Paris, 1887-1900 (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1998); Caroline Boyle-Turner, Les Nabis (Lausanne: Edita, 1993); Cogeval, The Time of the Nabis (Montreal: The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts), 1998; Elizabeth Easton, The Intimate Interiors of Édouard Vuillard (Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts/ Washington: The Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989); Claire Frèches-Thory and Antoine Terrasse, Les Nabis (Paris: Flammarion, 1990); George Mauner, The Nabis: Their History and Their Art, 1888-1896 (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1978). A final category of Vuillard scholarship has focused on his decorative projects. See Gloria Groom, Édouard Vuillard: Painter-Decorator. Patrons and Projects, 1892-1912 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993); and Beyond the Easel: Decorative Paintings by Bonnard, Vuillard, Denis, and Roussel, 1890-1930 (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2001). 4. A comprehensive study of Vuillard's prints can be found in Claude Roger-Marx, The Graphic Work of Édouard Vuillard (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1990), an English translation of L'Oeuvre grave de Vuillard (Monte Carlo: André Sauret—Editions du Livre, 1948). See also François Fossier, La Nébuleuse Nabie. Les Nabis et l'art graphique (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale and the Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1993). 5. On the history of Vuillard's large-scale decorations, see Gloria Groom, Édouard Vuillard. For the relationship between Vuillard's small- and large-scale paintings, see Katherine Kuenzli, "The Anti-Heroism of Modern Life: Interiority and Intimacy in Vuillard's Vaquez Decorations" in The Anti-Heroism of Modern Life: Symbolist Decoration and the Problem of Privacy in Fin-de-Siècle Modernist Painting (Ph.D. dissertation, UC Berkeley 2002). 6. The New York Times (January 17, 2003). 7. See Gloria Groom, Beyond the Easel. 8. Elizabeth Easton makes an argument for the transitional nature of Vuillard's photographs in her catalogue essay, "The Intentional Snapshot," in Édouard Vuillard (2003), 423-438. 9. Seventy-nine entries for works dated 1900 or after appear in the 2003 exhibition catalogue. These numbers do not include the large number of photographs exhibited which span the turn of the century. For previous important retrospectives, see John Russell, Édouard Vuillard 1868-1940 (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario/San Francisco: California Palace of the Legion Honor/Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1971) and Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, Édouard Vuillard (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art/New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1954); The 1990 Lyons retrospective of Vuillard's work divided its selection equally between pre- and post-1900 works. The interpretive emphasis in the catalogue, however, was on Vuillard's Symbolist period. In her essay on Vuillard's late portraits, Dominique Brachlianoff underlines the artistic superiority of Vuillard's Symbolist work. See Vuillard (1990), 173-196. 10. Carnduff-Ritchie is unequivocal in his assessment that "when all is said by way of extenuation, and however one may try to select later work that reflects something of Vuillard's original genius, the fact remains that the progress of his art during the last twenty-five years of his life, until his death in 1940, appears to us now as retrogressive, if not reactionary," Édouard Vuillard (1954), 26. Russell's judgment is more gentle, though not different in its underlying message: "People often discuss Vuillard in terms which imply the prefix 'If only. . .': if only he had gone on to invent abstract painting, if only he had continued the Mallarméan vision of the 1890s, if only he had dictated to Nature. And of course art history. . .would. . .have been different. . .if Vuillard had not reverted to the formal devices of an earlier generation after 1900, toiling to give an account, as veracious as he could make it, of complex and often unrewarding visual situations," Édouard Vuillard (1971), 70. 11. See Cogeval, "Backward Glances," in Édouard Vuillard (2003), 1-50; and Cogeval, "Le Célibataire mis à nu par son theater même," in Vuillard (1990), 105-136. 12. Cogeval in Vuillard (2003), 46. 13. Ibid., 42. 14. Cogeval indicates as much by the title of his 2003 catalogue essay, "Backward glances," Édouard Vuillard (2003), 1-50. 15. Ibid., 22. 16. For a fuller account of Vuillard's interior aesthetic, see Katherine Kuenzli, "The Anti-Heroism of Modern Life: Interiority and Intimacy in Vuillard's Vaquez Decorations," 44-101. 17. Laurence des Cars in Vuillard (2003), 369. 18. Edmond Duranty, "La Nouvelle Peinture," in The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874-1886, ed. Charles S. Moffet (San Francisco: The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), 481. Translation mine. This much is corroborated by Vuillard's own reading. Though it is likely that Vuillard first came across Duranty's famous pamphlet as a student in the late 1880s, he did not become a true follower until the twentieth century (specific mentions of it can be found in his letters and journal in the 1930s). On this point see Vuillard (2003), 357. There exists a 1946 edition of Duranty's pamphlet dedicated to Vuillard by Marcel Guérin: "À la mémoire de Édouard Vuillard qui nous a fait connaître cette brochure," La Nouvelle peinture (Paris: Floury, 1946). Reports of Vuillard's interest in Duranty after 1900 have led to some confusion about the significance of Duranty to Vuillard's career. André Chastel claims the relevance of Duranty's pamphlet for Vuillard's painting in the 1890s, citing Duranty's famous passage about the reflection of an individual's identity in his domestic, material surroundings as evidence. See André Chastel, Vuillard, 28-30. Chastel's claim has been furthered in subsequent secondary literature on Vuillard. See Ritchie, 12-13; Russell, 17-18; Easton, 36; Ann Dumas and Guy Cogeval, eds., Vuillard, 182-183; Claire Frèches-Thory and Antoine Terrasse, Les Nabis, 73. Chastel's claim, however, is not supported by evidence from Vuillard's career in the 1890s. One only needs to read Vuillard's journal in the early 1890s to learn the extent to which he attempted to free himself from any association with Naturalism and Realism in painting. Vuillard looked to Duranty only when he turned away from Symbolism and became a portraitist of the high society after 1900.

|