The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

"Art, Cheap and Good:" The Art Union in England and the United States, 1840–60 "Alas, it is not for art they paint, but for the Art Union." |

||||

| The "Art Union" was a nineteenth-century institution of art patronage organized on the principle of joint association by which the revenue from small individual annual membership fees was spent (after operating costs) on contemporary art, which was then redistributed among the membership by lot. The concept originated in Switzerland about 1800 and spread to some twenty locations in the German principalities by the 1830s. It was introduced to England in the late 1830s on the recommendation of a House of Commons Select Committee investigation at which Gustave Frederick Waagen, director of the Berlin Royal Academy and advocate of art unions, had testified. By 1850 there were some thirty art unions in the United Kingdom and Ireland. I also have found evidence of them in France, Australia, and New Zealand. The Art-Union of London (AUL) was the first and largest art union in Britain, and it was unique among art unions by its distribution of coupons with which to purchase art rather than art itself. The American Art-Union (AAU) was established in New York in 1842. Although art unions appeared in five other United States cities by 1850, the AAU was the largest in America. | |||||

| The Art Union's influence and membership were unparalleled among contemporary art institutions,2 producing a relatively simple and effective institutional form of private patronage for the middling classes. Subscribers paid an annual membership fee (one guinea in London, five dollars in New York)3 and in exchange received a copy of the usually voluminous annual report and a copy of at least one specially commissioned engraving; members of the AAU in New York also received one chance in an annual art lottery for works of art already purchased by the AAU, and those in London received a chance for prize-coupons issued by the AUL with which paintings could be purchased from a number of London galleries (figs. 1, 2).4 | |||||

| The AUL and the AAU were so large at mid-century that both, in their own way, were swept up in an inflated sense of their own power and historical significance. By 1847 the AAU believed that it "possess[ed] the power to do more good or harm to the cause of Art in America, than any other society or body whatsoever."5 Likewise, by 1854 the AUL believed that "The history of the Art-Union of London, when it is written in after times—and no account of the progress of the Fine Arts in this kingdom will be complete without reference to that history—will form a very extraordinary chapter."6 Yet by the end of the nineteenth century the art unions had all but vanished.7 In fact, in the biographies of hundreds of individuals who served as Art Union officials there are only two references to the Art Union, despite the fact that some of these officials served for up to thirty years, sometimes meeting weekly.8 An erasure of this scale suggests that over time the cachet originally gained from Art Union service either eroded or was transformed into a source of embarrassment. How could these institutions, which commanded the attention of thousands of members at mid-century, fall into such disfavor by century's end? | |||||

|

Superficially, the AUL and the AAU were strikingly similar institutions. They were structurally identical save for the fact that the prizes in New York were purchased by the AAU and in London directly by prizewinners. Their rhetoric was often identical-each sought to promote taste among the middling classes and to provide much-needed patronage for contemporary artists. Both achieved enormous and immediate success yet were criticized for lowering the quality of art produced by increasing the quantity. Both were challenged as illegal lotteries. However, the strong parallels in institutional form, rhetoric, and trajectory led to quite different outcomes and to the patronage of significantly different art. |

|||||

| The Art-Union of London The AUL was established in 1837 on the recommendation of an 1835 House of Commons Select Committee on the Arts and Manufactures in the United Kingdom, which had concluded that access to art exhibitions, art education, and even art patronage by the middling and "operative" classes was a pressing economic and cultural imperative if Britain was to secure international cultural and economic dominance.9 An art union was recommended as one means to achieve this goal.10 |

|||||

| The first meeting of the AUL was led by four zealous young social radicals: Edward Edwards, writer and later proponent of public libraries in Britain; Henry Hayward, Edwards' brother-in-law; George Godwin, architect and social reformer; and Lewis Pocock, the only upper-class member of the group. Seven more established but less involved individuals joined at the second meeting: Edward Hawkins, Keeper of Antiquities at the British Museum; Benjamin Bond Cabbell, M.P. and patron of the arts; John Britton, publisher, writer, and friend of Godwin; Henry Thomas Hope, M.P. and member of the 1835 Select Committee; Benjamin Hawes, M.P. and member of the 1835 Select Committee; Henry Atkinson, a geologist; and a Mr. Webb, about whom little is known.11 By the end of 1837 a formal Committee of Management was in place which included Charles Barry, architect (who served on the committee for two decades); William Ewart M.P., chair of the 1835 Select Committee (two decades); N. W. Ridley Colborne, M.P. and member of the 1835 Select Committee (two years); George J. Morant, witness at the 1835 Select Committee (eight years); and the future duke of Northumberland, Lord Prudhoe (two decades). | |||||

|

The AUL was governed from its inception by the passionate young social reformers Edwards, Godwin, Pocock, Hayward and several radical Members of Parliament. Though radical, the long-term core of the management committee was also loyal.12 Of the original 1837 committee members, nine were still serving in 1859, and from the first three years of operation sixteen committee members served at least nineteen years. The radical members of the AUL recognized the need to acknowledge (and harness) the power of the emerging middle class, but they also recognized the significance of retaining aristocratic patrons. In the first twenty years of the AUL, the organization was presided over by two peers—the duke of Cambridge, who served from 1841 to 1847, and Lord Monteagle, who served from 1852 to 1866. Its vice presidents included the marquis of Northampton, Lord Compton, Lord Prudhoe, the bishop of Ely, Lord Londesborough, the earl of Arundel and Surrey, and Lord Monteagle (1844–52). Fifteen Members of Parliament served on the committee between 1837 and 1859. This combination of social reformers and the socially prominent seemed politically and culturally unassailable at a time of political and social uncertainty. |

|||||

| The AUL started slowly. In 1837 it raised only £480; by 1842, however, annual subscription revenue stood at almost £13,000—a figure that would remain fairly stable for twenty years.13 As an incentive for membership, the AUL awarded prize coupons which prizewinners could exchange for a work of art of their choice at one of a number of London art galleries. This system of self-education represented the philosophical core of the AUL.14 The policy was criticized by the press, by three government investigations, and by Prime Minister Robert Peel (on the grounds that it cultivated mediocre taste and the production of mediocre art), but on prize distribution the AUL resolutely and successfully resisted compromise.15 | |||||

|

George Godwin firmly believed in universal access to the fine arts and thus universal agency.16 He advocated in AUL Reports (which were drafted by him until 1869) that a number of economic, moral, social, and national cultural benefits could accrue from exposing the middle and industrial classes to fine art. He joined a number of witnesses from the 1835 Select Committee in maintaining that a knowledge of the fine arts exerted a civilizing and refining force on Britain's still rough and uneducated masses.17 Some of Godwin's AUL colleagues shared his extreme reformist views, but to those who had more direct contact with manufacturing his idealism represented a useful solution to more pragmatic concerns. As the 1835 Select Committee suggested, a visually educated workforce could improve British design and enable England to compete more successfully in international manufacturing.18 |

|||||

| It is likely that the committee members from Britain's emerging business—based ruling class established the AUL on a "modern" business model. The AUL promoted open access to works of art (consumers/members) and to art markets (producers/artists). It literally advocated a "free trade in art," with mailed engravings and reports as its "paper currency."19 In order to attract large numbers of consumers, the product (engravings and reports) was deliberately inexpensive, hence Godwin's slogan "Art, Cheap and Good."20 The distribution system (by mail) was fast and efficient, and advertising was visible and widespread. In order to insure the greatest impact, the AUL also curried favor with S. C. Hall (editor of the only-just independent but highly influential Art Journal) to publish all AUL documents and reports, and to promote heavily the AUL's annual exhibition of its prizes.21 | |||||

| The AUL was successful in its dealings with members, but its relations with other art institutions were mixed at best. Its interaction with the Royal Academy was somewhat adversarial from the outset, but many established critics, including John Ruskin, were openly hostile.22 As AUL membership grew, the organization increasingly was subject to criticism from those who stood to lose the most if the AUL succeeded in disrupting London's artistic status quo—i.e., those mainstream artists and institutions that did not benefit directly or financially from the AUL.23 Ironically, the first organized opposition to the AUL came from a delegation of print sellers and publishers of inexpensive prints whose businesses were threatened by the widespread distribution of AUL prints and who threatened prosecution under an arcane Lottery Act which stipulated that any individual who participated in a lottery was liable to a £20 fine.24 The complaint seemed just. The AUL was accused of publishing relatively good prints with which inferior "cheap prints" could not compete. The influential members of the AUL's management committee mobilized in reaction. In 1844 Lord Monteagle managed to secure a House of Lords bill temporarily legalizing Art Unions, and Thomas Wyse, M.P., called for an 1845 House of Commons Select Committee on Art Unions and installed himself as chair.25 In 1846 the AUL, sponsored by its president, the duke of Cambridge, was granted a Charter of Incorporation, thus establishing its permanent legality.26 | |||||

| Although the AUL survived this initial legal assault, it was wounded nonetheless. The generally sympathetic but exhaustive Select Committee investigation almost accidentally uncovered a number of fairly broad issues regarding the AUL that it found troublesome. The Committee of Management was widely perceived to be closer to a gentleman's club than a representative governing board. Even though the committee was inarguably stable and election to it was by nomination of another member, it hardly reflected the AUL's mostly middle-class membership (aside from a schoolmaster who joined the committee in 1859).27 As a witness in the Select Committee investigation, William Bucknell of the Board of Trade supported the print dealers' charge that the bulk production of engravings (and other art) represented unfair market competition.28 The artist Richard Redgrave, among many others, asserted that the art of engraving had been degraded by the speed of production required by the AUL, by the poor quality of many thousands of prints pulled from a single plate, and by fact that the AUL made engraving "common" in an art world that increasingly linked "value" to rarity.29 | |||||

| The chronic lengthy delay of annual AUL engravings (sometimes for several years), the many thousands of copies of a single image in circulation, and the inferior quality of the last prints pulled from a single plate were the chief sources of criticism. The AUL acknowledged that the physical quality of prints issued at the end of a press run was a serious problem, one which they tried to resolve by offering a choice of prints. It also tried to reduce production time by selecting prints several years in advance of distribution. On the issue that its prints were "common," however, the AUL made no apology: its avowed purpose was to expose the greatest amount of art to the greatest number of people. On the charge that AUL prints were taken from inferior art, the records show that of the thirty-four prints (and sets) offered between 1838 and 1859, eighteen were from paintings by academicians, eighteen were historical subjects, six were landscapes (including one by Turner in 1858), and nine were genre images (including two by Frith).30 Yet the quality was admittedly uneven. The subjects of many of the prints suggested "higher" art, but the images themselves were frequently rendered in an openly sentimental manner, presumably designed to attract subscribers.31 | |||||

| Redgrave also charged that the AUL forced artists to produce smaller, lower-grade pictures to attract AUL subscribers.32 An 1846 Board of Trade investigation reiterated widespread dissatisfaction among the art world elite with the AUL's tacit endorsement of mediocre art through its prize-distribution policy.33 William Frith defended AUL prizewinners, arguing that by the time they received their prize coupons most of the good art had already been sold to art dealers and private patrons, often before exhibitions even opened.34 In fact, most of the higher-priced prize purchases were actually selected from Royal Academy or British Institution shows, although by 1859 the AUL had reduced the number of prizes valued between £100 and £200 to three, between £20 and £30 to forty-four, and between £10 and £15 to forty-six. The fact that history paintings tended to be bought with larger prizes and that most other purchases were small landscapes and genre paintings by relatively unknown artists probably was more an issue of cost and availability than lowbrow taste.35 | |||||

| An analysis of AUL prize purchases indicates that prizewinners chose mostly domestically scaled, somewhat moody local landscape or heavily sentimentalized genre paintings. Of the major prize purchases between 1837 and 1852, four were rather weepy historical scenes by Charles Landseer, one was Daniel Maclise's Sleeping Beauty, and one was John Martin's Flight into Egypt. The others were an uneven eclectic mixture of British landscapes, dramatic historical or literary scenes, overtly exotic images such as Jacobi's Arabian Nights, and saccharine representations such as Harvey's Blowing Bubbles. On the other hand, AUL special commissions–for example, a series of seventeen medals representing Britain's greatest artists and architects from 1848 to 1871 or Thornycroft's bronze equestrian statuette of Queen Victoria–tended to be ambitious, patriotic, and significant.36 | |||||

| There is no evidence that prizewinners were unhappy with their purchases. In the 1840s the AUL instituted an annual exhibition of prize selections with the triple purpose of trying to appease critics with full disclosure of purchases, to encourage visitors and thus new subscriptions, and to "encourage" prizewinners to choose "better" paintings. These exhibitions were extremely popular (the AUL regularly reported upwards of 200,000 visitors at its annual shows) but there was little change in quality37 and both the press and the London art world were unrelenting in their condemnation of these exhibitions. An 1846 Topic article suggests a motive: "We cannot but fear that the opposition to such institutions has a touch of aristocratic self-sufficiency, and a fear lest mental luxuries should be degraded by being shared by the people."38 | |||||

|

In 1847, the AUL's first year of full operation, subscription revenue reached an all-time high of £17,871; in the following year, however, as a wave of revolutions and economic instability swept Europe, subscription revenue dropped by almost £5,000, and was reduced further (by £2,000) a year later. There was a slight rebound in 1850 and 1851, but in 1852, when the AUL distributed Frith's English Merrymaking (engraved by W. Holl), subscriptions rose by £1,500. |

|||||

| In an attempt to boost declining membership in the wake of financial uncertainty in England and war in the Crimea, the AUL commissioned the engraving of William Frith's immensely popular painting Ramsgate Sands, called Life at the Seaside (figs. 3, 4), for eventual distribution in 1859,39 capitalizing on its success at the 1854 Royal Academy exhibition. Frith had broken with custom by selling this very large work (153 x 76.2 cm [60 1/4 x 30 in.]) to the picture dealers Messrs. Lloyd prior to exhibition. Lloyd's sold it to Queen Victoria at no profit but retained the engraving rights. The painting drew thousands of visitors to the Royal Academy exhibition and dozens of reviewers helped publicize it to the reading public. The composition, which depicts a multitude of fashionable middle-class visitors to Ramsgate beach, is crowded and bustling; its narrative is visually accessible and full of interesting detail. The AUL recognized immediately the potential popularity of the image for its own middle-class members and had secured exclusive permission to engrave it. The engraving, which was the AUL's largest offering to date (106.7 x 53.3 cm [42 x 21 in.]), was also its most successful.40 It cost the AUL almost £7,000, roughly half of its 1859 budget and £2,300 more than it spent on prizes,41 but AUL subscription revenue jumped 30 percent, from £11,710 in 1858 to £15,210 in 1859, and one thousand prizes (and prize-coupons) were distributed by lot.42 | |||||

| Despite the popularity of a few engravings, such as Frith's Life at the Seaside, the long-term impact of the AUL on English art (and the London art market in particular) turned out to be relatively small. Almost no AUL engravings or prize paintings are remembered today. Most of the prize purchases were small and deemed unworthy of attention by the mainstream art world, both then and now. Ironically, the AUL's hope that the middle class would educate itself was realized, at least to some extent. Thousands of works of art were purchased and many hundreds of thousands of visitors attended AUL exhibitions. The established art world (even AUL officers) had been unable to imagine an independent middle-class taste that reflected their particular experiences and cultural desires beyond "correct" taste. In 1859, however, the production of Frith's Life at the Seaside represented one moment in AUL history when the desire of the management committee to distribute a great work of art, the desires of the membership for an image of themselves at leisure, and the desires of art critics for high art all coincided. That year members set records for subscriptions, established that they subscribed primarily for the annual engraving not just for the chance of a prize, and suggested the tantalizing idea that AUL members actually knew a good work of art when they saw one. | |||||

|

The American Art-Union |

|||||

| The makeup of the management of the AAU was strikingly different from that of the AUL. Its first president, John W. Francis, was a wealthy physician and part of the famous "Hone Set."47 The first treasurer, Francis W. Edmonds, was a Wall Street banker and director of the New York and Erie Railroad; he was also the only artist to serve on the committee. James Herring, the Apollo gallery director, originated the AAU and became its first corresponding secretary. The first recording secretary, Benjamin Nathan, was a broker. Of the full fourteen-member Committee of Management, six of them (George Bruce, Francis Edmonds, Philip Hone, William Kemble, William L. Morris, and Eleazer Parmly) were on Edward Pessen's list of the wealthiest New Yorkers;48 five can be positively identified as prominent Whigs (Philip Hone, onetime mayor of New York; J. Watson Webb, owner of the New York Courier and Enquirer; John H. Austen; George Bruce; and Duncan Bell).49 Indeed, most of the other committee members were equally wealthy, can also be connected to the "Hone Set," were members of the same social clubs, and can safely be assumed to have been Whigs. Only two members of the first committee, Prosper Wetmore (shipping) and John Nesmith (real estate), can be positively identified as either Democrats or Republicans.50 Thus the AAU Committee of Management was dominated for ten years by a relatively small group of wealthy, politically and socially conservative merchants, manufacturers, shippers, and newspaper men.51 | |||||

| The AAU had five presidents: John W. Francis (physician), 1839–41; Daniel Stanton (merchant), 1842–43; William Cullen Bryant (poet and newspaper writer), 1844–46; Prosper W. Wetmore (merchant and democrat), 1847–49; and Abraham M. Cozzens (merchant and art collector), 1849–53. Three members of the committee served the AAU over the course of its entire existence: Ridner (corresponding secretary, 1842–44), Austen (treasurer, 1846–53), and Wetmore (president, 1847–48). A fourth member, Cozzens, joined in 1840 and served as the AAU's last president (1849–53). All four individuals were merchants.52 Among roughly eighty-three committee members, an estimated thirty-four were merchants, eleven were lawyers, seven held public office, and twelve were involved in publishing. Four members were auctioneers, one was a doctor, one a dentist, one a gallery owner (Herring), and one an artist/banker (Edmonds). The mix was significantly different from that found in the AUL. The AAU management committee was a tightly knit group bound together by social and business interests. Many of them gathered socially in committee member John R. Bartlett's famous bookstore housed in the Astor House Hotel, also a favored society meeting place of the 1840s.53 Most of the members of the AAU committee represented first- (or at most second-) generation wealth and came directly from the business world, having amassed huge fortunes in commerce, shipping, and communications. Most were politically conservative, supported the social and political status quo, and rejected the social radicalism of the AUL. Few had any real training in the visual arts yet were deeply convinced that their collective artistic taste was America's taste. | |||||

| The AAU management committee generally held that America's republican form of government would be fundamentally undermined by an open democracy; hence, the committee resisted external pressure to transfer the power to purchase art to AUL's middle-class members. Rather, the cornerstone of AAU philosophy was that its committee should serve as both the arbiters and guardians of an emerging national American art.54 The AAU seemed to echo George Godwin's belief in universal access to art by borrowing rhetoric such as "a love of art is a universal feeling" or that AAU art should reach "the humblest individual in society . . . in the most remote parts of the union."55 But these statements were carefully worded. True, the AAU was greedy for subscribers, yet nowhere in all of its many publications did AAU management extend to its membership the right to judge art. In fact, by 1848 the AAU had constructed a self-promoting system of distributed words and images in the form of engravings, prizes, and the Bulletin of the American Art-Union which propagated, explained, and justified what the AAU Committee described as "correct [i.e., Art Union] taste." 56 It is important to note, however, that "official" AAU taste was mostly that of newly rich entrepreneurs and not that of the old New York aristocracy, and as such was much closer to the artistic taste of its membership at large than AAU officers would have liked to believe—and a significant factor in its financial success. | |||||

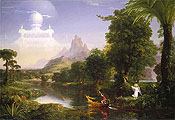

| The AAU also appropriated the AUL's concept of the fine arts as a civilizing force, though it did not set itself the task of refining its members' taste; rather, it took on the more ambitious task of cultivating (as in creating) taste in America, echoing numerous contemporary opinions when it wrote: "Our countrymen have been too often charged with an indifference to all pursuits not tending to the accumulation of wealth."57 To the AAU, "taste" was "the angel that drives the money-changers from the temple of the mind."58 Nevertheless, much of the AAU's self-generated rhetoric was cast in the language of contemporary business and it certainly was operated as such. Like the AUL, the AAU fully exploited "modern" business practices by promoting membership as a financial investment: risk a small amount of money (five dollars) for a potentially high return (a painting). Furthermore, it depended on mass participation, presented for inspection in its gallery the works being offered as prizes, advertised widely in all the major New York journals and newspapers, and had a fast and efficient production and distribution system for the Transactions (and, later, the Bulletin) and its engravings. Remarkably, the AAU managed to place Cole's Youth in the hands of subscribers less than a year after the painting was exhibited in the AAU gallery. Although AUL business more than likely involved not insignificant inside dealing, especially with respect to engravings, the London organization seems to have used business techniques primarily to facilitate its operation; the AAU, however, seemed almost incapable of separating business goals from the organization's loftier goals. AAU committee members apparently saw little conflict of interest in such practices as promoting their favorite artists to the AAU, purchasing from the same artists paintings for the AAU and for their personal collections, and, in particular, enhancing the value of their Thomas Cole paintings by exhibiting them as part of the AAU's 1848 promotion of Cole. | |||||

| Thomas Cole's large four-part series Voyage of Life (figs. 5-8; each approximately 134.6 x 203.2 cm [53 x 80 in.]) had been tremendously popular with American audiences since its creation in 1840.59 Produced originally for a private patron, Samuel Ward, Voyage of Life is a dramatic and accessible religious allegory that chronicles one man's spiritual journey through infancy, youth, manhood, and old age. The images resonated with America's sense of social and religious uncertainty intermixed with a waxing national cultural identity in the 1840s.60 When Cole died prematurely in 1848, the AAU (which previously had purchased eight of his paintings), the National Academy of Design, and the New York Gallery of the Fine Arts jointly organized a widely promoted memorial exhibition, which included Voyage of Life as well as seventy-two other Cole paintings, at the Perpetual Free Gallery. Nineteen works came from the collections of nine AAU officers.61 William Cullen Bryant's heartfelt eulogy was reprinted both in the catalogue of the exhibition and in the Bulletin of the American Art-Union. Bryant, a future president of the AAU, described Voyage of Life as "a perfect poem" and Youth, specifically, as "one of the most popular of Cole's compositions."62 The Reverend Gorham D. Abbott estimated that roughly 500,000 people visited the show (a rather generous number, equivalent to half of New York's population).63 | |||||

| The AAU saw an opportunity to revitalize itself. In 1848 it offered the entire Voyage of Life series as a single prize in its annual art lottery. The chance to win the series, originally commissioned by Samuel Ward for $6,000 in 1839, or one of the other 453 paintings in the lottery for a mere five-dollar subscription caused AAU membership to jump from 9,666 to 16,475 in a single year. The following year the AAU offered an engraved version of Youth (fig. 9), the second painting in Cole's series, as one of the two subscription offerings.64 Membership jumped to an all-time high of almost 19,000 in 1848 and brought in a staggering $94,800. | |||||

| Most of America's leading artists sold a surprising number of works of art to the AAU. Of the thousands purchased by the AAU, most were slightly larger-than-average, domestically scaled landscape and genre paintings; a few were much larger, but now mostly forgotten, history paintings. Cole had sold about twenty landscapes to the AAU; Durand sold forty-three, Cropsey forty-four, Kensett forty-six, and Church twenty-nine. Mount sold five genre works; Bingham sold twelve, Woodville seven, and Spencer eight. Huntington sold a remarkable forty-five works of art of various subjects, including history; Leutze sold twelve, and so on.65 Some of these works are small and untraceable, but many can be traced to collections today, indicating that they are now, as then, judged to be significant contributions to American art. Moreover, the parallel between AAU subscriptions and the sheer number of works purchased from America's leading artists is indicative of an unusual consensus in taste between AAU officers and members. | |||||

| The AAU purchased Voyage of Life for distribution in an attempt to stave off its increasingly serious credit problems.66 When it was formally established in 1842, the AAU had purchased works of art directly from artists as subscriptions came in. Most AAU subscribers lived close enough to New York to subscribe in direct relation to what was exhibited at the gallery, however, and over the years members renewed later and later, waiting to see in the AAU gallery what they might win before paying their five-dollar dues. A financial game of chicken developed between members, who waited until art worth winning was exhibited in the gallery, and officers, who could purchase art only as subscriptions were received. By 1 August 1848 the committee had purchased only 115 paintings. It bought an additional 224 in the next four months but had to scramble to buy 115 works in the last twenty days of its fiscal year. The 1848 budget eventually closed out at a healthy $86,368, with an increase of almost 6,000 subscribers over 1847, but late subscriptions had forced the purchase of almost one quarter of the collection in a mere twenty days. If the AAU had offered Voyage of Life only as a strategic attempt to encourage early subscriptions, the effort clearly failed. I estimate that half of the 16,475 subscriptions for 1848 were paid in the last three months of that year, creating extreme credit problems as well as sending to its critics the clear but unfortunate message that most subscribers joined the AAU for its art lottery rather than for art edification. | |||||

|

A journeyman from Binghamton won Voyage of Life. In 1849 the AAU, which had retained the engraving rights, offered a large (38.7 x 57.8 cm [15 1/4 x 22 3/4 in.]) engraving by John Smillie of Youth as one of two prints distributed that year. The AAU hoped that by distributing Youth it would be able to consolidate the gain in subscribers from 1848, and, perhaps more important, help direct members' interests away from the lottery and toward the guaranteed benefits of AAU membership-the engravings and publications. The AAU advertised Youth as the frontispiece illustration to its 1848 Transactions,67 and in 1849 it garnered nineteen thousand subscriptions. But the 1849 engravings cost the AAU almost half its $96,000 budget, leaving (after administrative costs) about $40,000 for the purchase of 460 paintings-roughly the same figures as for 1848. Unhappily, while membership had increased by 3,000, there was no corresponding increase in the total number of available prizes. Subsequently, in 1850 membership dropped back to its 1848 level. | ||||

| The AAU Committee was strongly represented by business members, by the popular press, and by the bar, so it was surprising that it fell afoul of both the press and the law in 1849 and 1850 when it became embroiled in a nasty and very public squabble with a newly founded International Art Union. The New York Herald's vitriolic James Gordon Bennett led a group of editors and writers in charging the AAU of "clannishness," abuse of power, financial mismanagement, and operating an illegal lottery.68 The AAU, for its part, responded by publishing a heated article on the "Enemies of the Art Union."69 The public exchange of insults (which was both personal and unrestrained) destroyed the AAU's reputation. It lost 3,000 members in 1850 and found itself so financially strained it was forced to postpone its lottery.70 Bennett presented the AAU's financial embarrassment as evidence of mismanagement, to which the AAU responded by suing Bennett for libel. The suit failed, but Bennett countersued nevertheless. In a bizarre twist, Henry J. Raymond used his political influence with New York District Attorney N. Bowditch Blunt to hear the case, fully convinced that it would fail,71 but the AUL lost both the case and its appeal. In 1851, when annual membership dues did not cover its expenses, the AAU ceased operation. Its assets were subjected to a public sale on 15-17 December 1852 in order to clear all but $2,384 of its debts.72 This ended the activity of the AAU as an organization, although its Committee of Management was subjected to further investigation. A Select Committee of the Assembly of the State of New York was appointed on 15 April 1853 to inquire into the affairs of the AAU.73 It concluded that there was "no necessity for any further legislative action."74 The report was published by the New York Daily Times.75 That, except for a "Memorial of the Committee of Management" of the American Art Union addressed to the Honorable Assembly of the State of New York reported in the New York Daily Times, 23 June 1853, p. 2, was the last public discussion of the AAU. Shamed and disgraced, the AAU dissolved, and its committee members—several of whom had made exceedingly good purchases at the 1852 sale76—fled from its taint and erased it from their biographies. | |||||

| The Legacy of the Art Union Interestingly, two of the major charges that had been leveled against the AAU by the American press—the illegality of its lottery and the mediocrity of its prizes—were identical to charges brought against the AUL. But members of the AAU's management committee had also been accused of being corrupt, self-serving individuals who underpaid artists for paintings, played favorites, were biased in purchases, and exerted questionable taste.77 The committee had even been described as "a set of rich ignoramuses."78 The AAU responded by arguing that while some of its committee members "gave more attention to its business than others," an adequate system of rotation of officers ensured the highest level of professionalism among them. The committee acknowledged overpaying, but not underpaying artists: "In the early days of the institution, when it was not easy to find paintings in which to invest our little funds, we bought everything at the highest price . . . but we soon stimulated production, so that we were overwhelmed with . . . trashy productions . . . [and] thus discrimination was [now] necessary."79 They also admitted that while most purchasing decisions were made on merit alone, there were other considerations, such as the relative quality of a painting as compared to the artist's previous work, the cost of the work of art, the financial need of either meritorious or "young and poor artists,"80 and conceded that at times quantity necessarily took precedence over quality.81 |

|||||

| As evidence of the quality and merit of its purchasing policies,82 the committee cited a list of paintings purchased since 1839.83 In examining this list it is indisputable that the AAU dominated the New York art market in the 1840s. Most AAU artists were and still are considered New York's preeminent artists. Early purchases were sometimes quirky, very inexpensive, and mostly by lesser artists. By 1844, however, the range of paintings purchased was actually rather impressive. An examination of the 1848 list (the year of Thomas Cole) indicates that of 464 prizes, 283 were landscape paintings (four comprised Voyage of Life), 125 were genre paintings. Only about 25 were history paintings (they were large and expensive), but then only 25 were small still-lifes. Of the paintings that sold for more than $300 in the 1852 sale, an almost equal number were history, landscape, and genre paintings.84 This range of paintings does not represent a desire simply to please its members, but rather, I believe, the AAU's elevation of landscape and genre as dominant symbolic visual representations of the nation.85 | |||||

| Also, an 1848 list of 221 artists from whom the AAU purchased art contains about seventy very well-known artists and an additional eight or so well-known artists.86 Several successful American painters were cultivated by the AAU, among them George Caleb Bingham, Emanuel Leutze, William Ranney, and Richard C. Woodville.87 Quite a number of others sold multiple works to the AAU until 1848: D. W. C. Boutelle (twelve), Jasper F. Cropsey (eight), Asher B. Durand (six), Sanford R. Gifford (eight), Daniel Huntington (twelve), J. F. Kensett (nine), William Oddie (sixteen), and Thomas Addison Richards (nine).88 | |||||

| Engraving played an increasingly prominent role in the promotion of the AAU as the percentage of members living outside of New York increased; in turn, the importance of the gallery decreased. In 1840 just over one quarter of the budget was spent on paintings; one-twelfth was spent on the engraving. In 1844 half of the budget was spent on prizes, compared to roughly one eighth on the engraving. By 1849, however, less than half of the budget was spent on prizes and almost one quarter on engravings. The AAU produced twenty-six engravings between 1840 and 1851-fifteen were historical, four were landscapes, and seven were genre. History and the encouragement of "high art" was a clear priority until 1849. Nine of the first twelve engravings produced were historical and only one a genre image (Mount's Farmer's Nooning, 1843) was distributed without an accompanying historical image. In 1849, however, the AAU openly acknowledged the increased national significance of landscape and genre by producing Darley's Legend of Sleepy Hollow (genre) and Cole's Youth (landscape). In 1850 two landscape, one genre, and two historical works (one by Leutze) were distributed, and in 1851 one historical, two landscape, three genre engravings were distributed. | |||||

| The impact of the AAU on the fledgling New York art market was significant. Between 1849 and 1851 it spent about $125,000 on almost 1,300 paintings. In thirteen years, thousands of works of art had been purchased, twenty-six engravings distributed, and almost three million people visited the AAU gallery. When the AAU fell, it sent shock waves through a still unstable and shallow art market. The AAU as an institution vanished after 1853, yet I have found many hundreds of AAU paintings and several AAU engravings in museums around the United States. The AAU may have promoted its admittedly biased version of taste, but it seems that today's museum world, by and large, agrees with it. Cole's Voyage of Life, for instance, is now in the collection of the National Gallery, Washington, D.C.; Bingham's Fur Traders is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Bingham and Ranney have Art Union works at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts; and Church and Durand represent the AAU at the White House.89 | |||||

| The Art Union was both a product and agent of the industrial age. It was one of the first nineteenth-century art institutions to engage the emerging middle classes. Its extraordinarily flexible and immensely malleable organization allowed it to meet the diverse needs of the two very different art markets of London and New York in the 1840s without significant distortion of its essential form. Why then did the Art Union decline and disappear so resolutely? Both the AUL and the AAU were victims of their success. They confused growth with stability and popularity with legitimacy. The strength of the Art Union system was its flexibility, gained from operating annually as an independent financial unit capable of no-risk expansion and contraction. As the AUL and the AAU grew, each began to take on long-term contracts—art commissions in London and a gallery in New York—that compromised their ability to contract if subscriptions dropped. More important, perhaps, was the inability of their respective managing committees to predict the changes in increasingly impulsive and unstable memberships. In 1848 the AAU gained 6,000 new subscribers with Cole's Voyage of Life and in 1849 gained 3,000 more with Youth. Almost half of the 1849 subscribers were new members, however, and their future subscriptions could not be relied upon. The AAU committee failed to plan for a downturn; when it lost 3,000 members in 1850 it was bankrupted. | |||||

| In 1859 the AUL gauged correctly that its membership would subscribe to receive the engraving of Frith's Life at the Seaside (based on a fairly stable core of roughly 7,000 subscribers). The AUL was dedicated to an idealistic radical reform of the London art world and the agency of its middle-class subscribers in it yet, ironically, it had little impact on the London art world. Its prizes were selected from the margins. The institution did little more than pick up the slack in an overcrowded market. Only a handful of major artists ever made substantial contact with the AUL; the art purchased was mostly small, sentimental, and, by today's terms, on the edge of the British school. The AAU, on the other hand, was openly paternalistic. It did not want simply to aggregate its members' interests, it actively sought to shape their preferences. Its lack of faith in the ability of its middle-class members to educate themselves was coupled with a dogmatic faith that its own vision was the correct one. It is equally ironic that the AAU, despite its brief life, effected major changes in the New York art world. It helped to expand and transform the American school from a relatively provincial artistic backwater into a viable national school of art, in which deeply encoded and multilayered landscape and genre paintings came to represent America and its art. | |||||

| Both the AUL and the AAU seriously underestimated the political and legal power of their critics and, especially in America, the power of the popular press. Nevertheless, in the 1840s and 1850s in London and New York the Art Union created a space in which aesthetics, economics, technology, and communication came together, and where, with the success of Youth in New York in 1849 and of Life at the Seaside in London in 1859, and with different responses to very different historical and cultural forces, a strikingly similar event took place: a brief synergy between the artistic elite and the newly self-defining middle class. | |||||

|

1. Thackeray (1844) 1904, p. 213. Thanks to my research assistant, Keery Walker. 2. For example, in 1848 the National Academy of Design in New York had a budget of some $4,500 and in 1849 receipts totaled $2,753. Every painting sold at its 1843 exhibition was sold to the American Art-Union. 3. In the 1840s one guinea and five dollars were roughly equivalent. Members could hold multiple subscriptions. 4. The AUL prizes for 1859, for example, included twenty-six works at £10, twenty works at £15, twenty works at £20, twelve works at £25, twelve works at £30, six works at £40, four works at £50, two works at £75, one work at £100, one work at £150, and one work at £200. The list of institutions from which art could be purchased included: The Royal Academy, the National Institute of Fine Arts, the Society of British Artists, the British Institution, the Royal Scottish Academy, the Water-Colour Society, the New Water-Colour Society, the Royal Hibernian Academy, and the Society of Female Artists. 5. Transactions of the American Art-Union 1847, p. 24. 6. Godwin and Pocock 1854, p. 5. 7. Major sources on the AUL include: Select Committee 1835; AUL "Minute Book," 1837-47; Art-Union, 1839-48; Edwards 1840; "Art Unions of Germany" 1842; Donaldson 1842; Clarke 1843; General Meeting of Artists 1843; AUL, Prizeholders 1844; AUL, Prizeholders 1845; Select Committee 1845; "Art Unions" 1846; Art Unions, Their Object 1846; "Patronage and Art Unions" 1846; AUL, Regulations 1847; AUL, Prizeholders 1848; Taylor 1849; Select Committee 1866; "Art Unions and Art Lotteries" 1888; Avery and Marsh 1895; Godden 1961; King 1964a; King 1964b; Aslin 1967; Beulah 1967; King 1976; King (1982) 1985; Smith 1986; Hurtado 1993. Major sources on the AAU include: AAU "Papers," 1839-55; Bulletin of the American Art-Union, 1848-51; "Art Unions" 1851; Selden 1854, pp. 228-40; Whittredge 1908; Baker 1953; Bloch 1953; Miller 1966; Mann 1977; Harris 1982; Sperling 1986; Johns 1991; Troyen 1991; Klein 1995; Fowler 1996; Sperling 1997; Hills 1998. 8. Reference to the AUL is found in the biographies of Godwin and Pocock published in the Dictionary of National Biography. 9. Select Committee 1835, pp. iii-ix, pt. 1, p. 97, pt. 2, p. 31. 10. Ibid., pp. iii-ix. 11. Sources on AUL officers include: Pye 1845; Oakes 1855; Boase 1892-1921; Dictionary of National Biography 1963-64; Stenton 1976-81; Jeremy 1984-86; Beckett 1986. 12. Edwards resigned after two years, but Godwin and Pocock served as honorary secretaries for 32 and 45 years, respectively. 13. Select Committee 1866, p. 71. 14. This concept was echoed in Samuel Smiles's Self Help (although not published until 1860), which was widely known through lectures in the 1840s. 15. AUL, Prizeholders, 1848. 16. Godwin and Pocock 1842, p. 3. 17. Select Committee 1835, pp. iii-ix. 18. Ibid., pp. iii-ix, pt. 1, pp. 103, 116, 126. 19. Ibid. 1845, pp. ii-iv, pt. 1, p. 45, pt. 2, pp. 33, 50. 20. Godwin and Pocock 1850, p. 10. 21. The Art Journal was first published in 1839 as the Art-Union by Godwin's friend Samuel Carter Hall. In 1839 Godwin wrote to Edwards: "It is proposed (and this is a secret for a day or two) to publish a monthly newspaper devoted to Fine Arts…the name will be-the Art Union! And they promise to make our association an object of their care." Godwin wrote extensively for the journal, which claimed a circulation of around 30,000 in the late 1840s. King 1964a, p. 279. See also Maas 1976. 22. Ruskin promoted artistic education of the middle classes but he argued for a top-down system (closer to the AAU model) based on study in a well-ordered museum. He was opposed to the bottom-up system of the AUL. Jeremy Maas (1969, p. 44) described Ruskin's system as "well meaning tyranny." For Ruskin's condemnation of the AUL, see Ruskin 1885, p. 29. Thackeray equivocated on the AUL. For his support of it, see Sperling 1997, p. 409. 23. The leaders of this opposition were a delegation of print sellers and publishers: S.& J. Fuller, Hayward and Legatt, Thomas McLean, and Gwynne; see "Art Unions" 1846, p. 3. 24. Kelly. King (1982) 1985, p. 221. 25. Lord Monteagle (Thomas Spring-Rice) had just been named Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Russell government. He served as president of the AUL from 1852 until his death in 1866. Thomas Wyse served on the AUL Committee from 1846 until around 1850. 26. The duke of Cambridge, the Queen's uncle, was president of the AUL from 1841 until his death in 1847. Godwin and Pocock 1847, p. 12. 27. Select Committee 1845, pp. iv, 13, 15, 217. 28. Ibid. 1866, p. 657. 29. Ibid. 1845, pt. 1, p. 165; 1866, p. 641. 30. Ibid. 1866, p. 71. The average cost of prints was between £2,000 and £4,000. Life at the Seaside cost £6,980, almost half of the 1859 budget. 31. For instance, in 1845, The Convalescent, engraved by G. T. Doo after William Mulready; in 1847, Seizure of Mortimer, engraved by H. C. Henton after J. N. Paton; and in 1849, Sabrina, engraved by W. Frost after P. Lightfoot. 32. Select Committee 1866, p. 641. 33. AUL, Prizeholders 1848. 34. Art Journal 14 (1852), p. 269; 18 (1856), p. 280; 29 (1867), p. 273. 35. The Morning Post 1856, as reprinted in Godwin and Pocock 1856. 36. Both are now in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. 37. Godwin and Pocock 1847, p. 5. See also Art Journal 7 (1845), p. 321. 38. "Art Unions" 1846, pp. 3, 5. 39. On Frith and Ramsgate Sands, see especially include Noakes 1978, pp. 51-58, and Gillett 1990, pp. 69-100. 40. By 1865, when the AUL again distributed a Frith engraving (Claude Duval, 68.6 x 48.3 cm [27 x 19 in.], engraved by Lumb Stocks), the work not only failed to muster the needed extra subscribers but the AUL brought in £721 less than it had in 1864. 41. Engraving rights cost £3,000. Life at the Seaside (1854), which was engraved by C. W. Sharp, was returned to Queen Victoria in 1859. 42. Select Committee 1866, pp. 68, 71. 1849 was the AUL's most successful year. £17,000 was raised and 706 works of art were purchased by prizewinners. The increase was owing to AUL legalization that year. 43. Bulletin of the American Art-Union 4 (April 1851), pp. 17-20. The Perpetual Free Gallery was one of the first galleries to remain open at night (by gaslight) to allow working members to visit the exhibitions. 44. Mann 1977, p. 19. Mann estimates that the average population of New York was 400,000 between 1839 and 1841, and that during the same years the AAU gallery saw 250,000 visitors annually. 45. Bulletin of the American Art-Union 4 (April 1851), pp. 17, 18. 46. Transactions of the Apollo Association 1840, p. 16; Transactions of the American Art-Union 1845, p. 10; 1849, p. 166. 47. The "Hone Set" was a self-declared social elite that admitted only Hone's best friends; see Pessen 1972. Sources on the AAU Committee include: Goodrich 1856; Hall 1883; Wilson and Fiske 1887-89; Hone 1889; Stillman 1901; Fox 1919; Dictionary of American Biography 1926-36; Mott 1930-68; Fox 1934; Shoemaker 1936; Mott 1941; Young 1967; Pessen 1970; Pessen 1972; Pessen 1973; Klein 1995; Hills 1998. 48. Pessen 1972. 49. See Pessen 1970, 1972, 1973. The Whig Party was founded in 1824 but was not formally established until 1834. It remained a loose confederation of individuals bound by their opposition to Jacksonian Democracy. The Whigs generally held to the Federalist belief in republican rule by representation and opposed universal white-male suffrage, often referred to as "mobocracy." By 1854 the party had all but ceased to exist. 50. The Democratic Party is the oldest continuous political party in the United States. It was established to oppose the Federalist Party and its beliefs were based in Jeffersonian Democracy. Democrats (called Republicans or Democratic Republicans before 1824) believed in universal white-male suffrage and a limitation of the powers of the federal government. The party dominated American politics for the first half of the nineteenth century but lost power when it became deeply divided over the issue of slavery in the mid-1850s. The Anti-Slavery Republican Party was established in 1854. 51. These include John Ridner (merchant), Augustus Greele (merchant), William Morris (lawyer), William Kemble (merchant), Thomas Campbell (broker), Aaron Thompson (merchant), George Bruce (type founder), Duncan Pell (auctioneer), Eleazer Parmly (dentist), and James Gerard (lawyer). Several other major merchants with shipping interests specifically included: Sturges (merchant and director of the Illinois and Central Railroad, Leupp (banker and director of the Erie Railroad), and Roberts (shipping and railroad promoter). The AAU committee also included several prominent Whig newspaper owners and editors, including J. Watson Webb, W.C. Bryant, Charles F. Briggs, Henry J. Raymond, and Evert A. Duycinck. William Hoppin (owner and editor of Appleton's Cyclopedia) joined the committee in 1843, and in 1848 founded the AAU's principal mouthpiece in its last four years, the Bulletin of the American Art-Union. 52. Two other members of the committee who joined in 1842, Erastus C. Benedict (admiralty lawyer) and Andrew Warner (clerk of the court of common appeals), also served until 1853. 53. Astor House Hotel was managed by Charles A. Stetson, another committee member. 54. Transactions of the American Art-Union 1845, p. 15. 55. Ibid. 1844, p. 6; Transactions of the Apollo Association 1842, p. 7. 56. Transactions of the American Art-Union 1845, p. 15. 57. Ibid., p. 5. 58. Bulletin of the American Art-Union 4 (April 1851), p. 20, and Transactions of the American Art-Union 1844, p. 8. 59. For Cole, see New York 1848; Wallach 1981; Truettner and Wallach 1994; Voorsanger and Howat 2000. For Voyage of Life, see Wallach in Truettner and Wallach 1994, p. 110 n. 216. 60. Wallach in Truettner and Wallach 1994, p. 98. 61. G. F. Allen (one), G. W. Austen (two), D. C Colden (three), A. M. Cozzens (three), P. Hone (three), C. M. Leupp (two), J. N. Perkins (one), J. Sturges (three), P. M. Wetmore (one). New York 1848, p. 3. 62. Ibid., p. 45. Bryant's eulogy was delivered at the Church of the Messiah, New York, on 4 May 1848. 63. Wallach in Truettner and Wallach 1994, p. 98. 64. The other was Felix O. Darley's The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. 65. A full list of AAU purchases is published in Baker 1953, pp. 3-425. 66. The series was originally commissioned by Samuel Ward and probably came to the Art Union by way of Ward's son, also Samuel Ward, who was an Art Union officer in 1844, and who, by 1849, had run through his father's fortune. 67. Transactions of the American Art-Union 1848, p. 1 68. New York Herald, 14 February 1852, p. 3. See also Bulletin of the American Art-Union 1848, pp. 442-47; Bulletin of the American Art-Union 1849, pp. xiv-vi, 593-96; "American Art and Art Unions" 1850; "Fine Arts" 1850-51. 69. "Enemies of the American Art-Union" 1849. 70. The AAU owed $5,000 per annum on an 1847 debt to pay for the construction of a new gallery. 71. Selden 1854, pp. 228-40. 72. This sale was covered in the New York Daily Times, 16 December 1852, p. 3; 17 December 1852, p. 3; 18 December 1852, pp. 4, 6. 73. Select Committee 1853. 74. The testimony was reported by the New York Daily Times, 22 April 1853, p. 4; 30 April 1853, p. 3, 3 May 1853, p. 3; 4 May 1853, p. 3; 5 May 1853, p. 2; 6 May 1853, p. 2; 7 May 1853, p. 3; 10 May 1853, p. 3; 11 May 1853, p. 3; 12 May 1853, p. 3; 13 May 1853, p. 3; 14 May 1853, p. 3; 15 May 1853, p. 3; 16 May 1853, p. 3; 17 May 1853, p. 1; 18 May 1853, p. 3. 75. "American Art Union" 1853. 76. Baker 1953, pp. 295-309. 77. Home Journal, 10 November 1849. 78. Anonymous letter, 31 July 1849, American Art-Union, "Papers." 79. Bulletin of the American Art-Union 4 (April 1851), p. 18. 80. Transactions of the American Art-Union 1847, pp. 24, 26; ibid. 1845, p. 18. 81. Transactions of the Apollo Association 1839, p. 7. 82. Bulletin of the American Art-Union 4 (April 1851), p. 18. 83. Ibid., pp. 18-19. 84. Baker 1953, pp. 295-304. Bingham's Shooting for Beef, for example was purchased by the Art Union for $379; Boutelle's Trout Stream for $350; Church's New England Scenery for $500; Cropsey's Sibyl's Temple for $400; Hinckley's Wounded Duck for $384; Kensett's Mount Washington for $438; Leonori's Amazon and Children for $685; Peele's Children in the Woods for $300; Rossiter's Ideals for $1,075; Ranney's Marion on the Pedee for $745; and Woodville's Game of Chess for $542. 85. Transactions of the American Art-Union 1848, pp. 52-74. 86. Ibid., pp. 21-26. 87. Hills 1998. 88. Transactions of the American Art-Union 1848, pp. 21-26. 89. The current locations of AAU purchases can be traced through the Inventory of American Paintings before 1914, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM). The work of Colonel Merl Moore, an independent scholar at SAAM, however, is an invaluable resource. His papers are now housed in the SAAM Library. I want to thank Colonel Moore for his kind help with the above listed paintings. |