The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The parlor ballad is, perhaps, the defining musical form of the Victorian era. Although Britain was never “das Land ohne Musik,”[1] and operatic, choral, and symphonic music thrived in Victorian Britain alongside more demotic genres such as the brass band or the pit band of the music hall, it is in the domestic setting, with figures gathered around a piano, that the essence of Victorian music making can be found. Discredited after the mid-twentieth century as recorded popular music displaced home performance, and never acceptable to highbrow admirers of art song in the traditions of the German Lied or French mélodie, the parlor song has become almost a lost art form.

However, the discovery in the National Art Library (London) of a bound volume of songs relating to the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations of 1851, where the celebrated Greek Slave (1844, first version, Raby Castle, Staindrop) by Hiram Powers (1805–73) was prominently displayed, led to a concert performance in conjunction with the exhibition Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 at the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) in 2014.[2] The recordings available here are of two works performed at the concert: The Greek Slave Waltz by Louis Antoine Jullien (1812–60) and The Greek Slave, a ballad by J. H. Jewell (lyricist) and S. W. New (composer), both thought to have been published in the year of the Great Exhibition. The revival of these pieces adds an experiential, affective dimension to the range of contemporary responses to the statue explored in this special issue. Soprano Lucy Fitz Gibbon and pianist Lindsay Garritson developed a performance style that captured both the pathos and the necessary lightness of touch to bring these long-neglected works to life. The effect on the audience at the YCBA’s “Crystal Palace Soirée” was striking: such music is far more effective in performance than on the page.

Our investigation began with sheet music, which, often produced with a decorative cover bearing a lithographic illustration, was one of the publishing phenomena of the Victorian era. Music for voice and piano reached a mass audience only after the development in the 1830s of the upright piano, of which several models were shown at the Great Exhibition. This remarkable instrument—so familiar as to be largely ignored both by historians of art music and by scholars of material culture—became an essential item in the middle-class home. To play the piano was a refined accomplishment for any young lady with pretensions to gentility. Solo piano music would be performed at soirées, while songs and vocal duets with piano accompaniment were the most popular form of entertainment in the home.[3]

The distribution of printed music for popular songs was swift and widespread throughout the British Isles and the empire, taking the place of the traditional purchase of broadside ballad sheets from itinerant vendors. The lithographic illustrations on the covers of sheet music were a significant element in the Victorian cult of celebrity, perpetuating and extending the fame of singers such as Jenny Lind, “The Swedish Nightingale,” and illustrating events commemorated in song, such as the Indian Mutiny, battles in the Crimean War, and, in a more celebratory vein, royal jubilees and weddings. Sheet music, in short, became a global commodity, industrially produced and circulated through the latest communication networks. It is a symptom of the ways in which elite and popular culture were not always separate in the Victorian world.

Publishers of sheet music were quick to capitalize on the appeal of the Great Exhibition, whose six million visitors provided an unprecedented market for the sale of souvenirs. Visiting the exhibition was in itself a performance of respectability, and many of the visitors would have had a piano in their home. A large range of commemorative musical scores appeared, many of them with lavishly illustrated title pages. The bound volume of songs in the National Art Library reveals that large sculptural works, among the most dramatic and crowd-pleasing objects in the exhibition, swiftly became the most popular subjects for musical evocation, only challenged by the great diamond that inspired The Koh-i-noor Waltzes of C. A. Wickes.[4] Many works—such as George Arthur Barker’s The Temple of Peace—were titled after, and illustrated, the exhibition itself and its building.[5]

Henri Fisher’s piano piece The Amazon Polka was inspired by the large zinc Amazon (1839) by the German sculptor August Karl Eduard Kiss, one of the most celebrated sculptures at the exhibition.[6] A two-color lithograph by Thomas Jones represents both the sculpture and its enraptured and fashionable audience (fig. 1). Some sense of the intended audience for The Amazon Polka can be discerned from its dedication to Miss Louisa Tussaud, then aged about fourteen and a member of the family of waxwork artists. Fashionable, well-off, but by no means a member of high society, Louisa was a great-granddaughter of Marie Gresholtz Tussaud, whose celebrated establishment on Baker Street had opened in 1835 after three decades of touring the country, and quickly achieved fame among the shows of London.[7] A more robust musical work, The Amazon Galop by Karl Büller, also a tribute to Kiss’s chef d’oeuvre, was available in various forms, including a lively duet for cornet and trombone, perhaps indicating a working-class audience, since these instruments were associated with military or brass bands.[8]

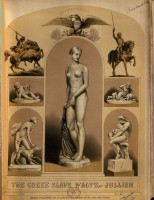

But the sculpture most often celebrated in music, as in so many other media, was Hiram Powers’s Greek Slave. A typical musical response to the sculpture can be found in The Greek Slave Waltz by Louis Antoine Jullien, the French composer of light music resident in London, whose promenade concerts were a feature of the season.[9] The Greek Slave Waltz was jointly published by the composer himself and the chromolithographic printers M. & N. Hanhart (fig. 2). The cover illustration was designed and drawn on stone by John Brandard (1812–63), an expert lithographer and lifelong collaborator with the Hanharts, whose firm was renowned for the use of a complex system of tint stones.[10] Carefully aligned in multiple registrations, these produced subtle tonal values.[11] The elaborate cover of The Greek Slave Waltz includes depictions of seven major sculptures, all widely reproduced. They are identified only by the country of origin, as if the page represented the meeting of nations at the Great Exhibition. Powers’s Greek Slave is placed centrally, in an arched space colored a delicate beige, which gives the effect of an architectural niche. Above the sculpture rises the eagle of the United States, a direct reference to the pasteboard eagle that was displayed prominently in the American section of the Great Exhibition. Clearly this publication, avoiding any suggestion of a critique of American slavery, was aimed at visitors from the United States or admirers of that nation. Selling at four shillings (compared to two shillings for The Great Polka of All Nations and a mere sixpence for England’s Welcome to All Nations), it was a relatively luxurious production.[12]

Jullien’s music opens with a pensive introduction, in which the piano, with copious use of the sustaining pedal, imitates a harp, before intoning a sad refrain that follows the general outlines of an aria from Italian popular opera of the period. However, the air of pathos is short lived, suggesting, perhaps, that the link between the music and its sculptural referent is somewhat superficial. The waltzes then proceed as series of variations on the melody. Despite its pretentions to be art music, this was surely intended to accompany dancing of the waltz, and after the introduction, little remains of the melancholy of the theme’s first statement. The slave and her tragic destiny are soon forgotten.

In contrast, The Greek Slave, a ballad inscribed to Hiram Powers, with words by J. H. Jewell and music by S. W. New, exploited the full range of sentiment (fig. 3). The cover is a crudely worked, unsigned chromolithograph showing the statue as it was displayed at the Great Exhibition, against a red curtain. But if the figure of the slave is depicted in monochrome on the cover, the music itself features a more extensive characterization. For in this case, the Greek slave herself sings, drawing a parallel between the body of the performer and that of the figure represented in the sculpture.

She fondly remembers “My childhoods lov’d home, Where my footsteps were free as the wind; . . . But my mem’ry recalls, recalls with a sigh These chains!”—here, the music rises to a climactic top G—“and reminds I’m a slave.” Only death can save the Victorian virgin from a fate worse than death. A sentimental denouement awaits. The pining slave, faced with a life as the sexual plaything of an unmentioned, presumably Ottoman, potentate, prefers to die. With sorrowful inevitability, then, “Hope, sweet enchantress” reminds the slave that “Thy sorrows are nearing the grave,” wherein lie “freedom and rest.” And here we almost cross over into the world of Victorian hymnody with “Thy spirit thus free’d, thus free’d from earths ties, shall give freedom and rest, to the slave.”[13]

Sheet music contributed to the interwoven circuits of celebrity in Victorian London. Famous singers became associated with music that evoked celebrated sculpture; and a mass audience gained access to, and vicarious proximity to, each of these phenomena through chromolithographic reproduction. This medium, like Parian ware and the plaster cast, allowed sculpture to enter the homes of all echelons of the Victorian middle class.

Thanks are due to Jane Nowosadko, senior manager of programs, Yale Center for British Art, for organizing the Crystal Palace Soirée and arranging for The Greek Slave Waltz and the ballad The Greek Slave to be transcribed. The transcription was ably provided by Natalie Dietterich. I am grateful to Lucy Fitz Gibbon and Lindsay Garritson for their performances, and for making their recordings available here.

[1] Oscar Adolf Hermann Schmitz, Das Land ohne Musik: englische Gesellschaftsprobleme (Munich: G. Müller, 1914).

[2] “Great Exhibition” [collection of music], EX 1851.100, Great Exhibition Collection, National Art Library, London. Cover illustrations of three of these scores were reproduced in Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt, eds., Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 323–24, cat. no. 116.

[3] Derek B. Scott, The Singing Bourgeois: Songs of the Victorian Drawing Room and Parlour (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1989).

[4] C. A. Wickes, The Koh-i-noor Waltzes (London: Cramer, Beale, 1851).

[5] George Arthur Barker, The Temple of Peace (London: Robert Cocks, 1851).

[6] Henri Fischer, The Amazon Polka (London: John Dumcombe, 1851).

[7] Richard D. Altick, The Shows of London (Cambridge, MA: Bellknap Press, 1978), 333–35.

[8] Karl Büller, The Amazon Galop (London: Jullien, 1851).

[9] Louis Antoine Jullien, The Greek Slave Waltz (London: Jullien, 1851).

[10] Joanna Selborne, “Brandard family (per. c. 1825–1898),” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), accessed September 18, 2013, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68913.

[11] Christine E. Jackson, “M & N Hanhart: Printers of Natural History Plates, 1830–1903,” Archives of Natural History 26 (1999): 287–92.

[12] Frances Anne Davidson (lyricist) and Henry Russell (composer), England’s Welcome to All Nations (London: G. H. Davidson, 1851); J. Cooper, The Great Polka of All Nations (London: for the author, 1851).

[13] J. H. Jewell (lyricist) and S.W. New (composer), The Greek Slave. Ballad Inscribed to Hiram Powers, United States (London: Jewell and Lethbridge, 1851).