The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Since his death in 1901, and indeed during his lifetime, prolific Victorian critic William Cosmo Monkhouse (1840–1901; fig. 1) has been labeled, quite deservedly, as conservative. From William Hogarth to the Pre-Raphaelites to Edward Poynter, over the last third of the nineteenth century Monkhouse consistently championed the English School of painting. He recognized a distinctive national style that he believed had emerged from unique cultural attitudes to history, a profound sensitivity to nature, and devotion to beauty. Despite his attachment to tradition, Monkhouse’s views on art and artists changed profoundly over the course of his career, most noticeably as he grappled with the tenets of Aestheticism and the works of James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). As he negotiated this period, when the attractions of pure form in visual art were a matter of vociferous debate, Monkhouse’s positions sometimes seem unresolved, his arguments still unfolding. To read Monkhouse, from his 1869 book, Masterpieces of English Art, through his 1899 compilation, British Contemporary Artists, along with the writings of some of his colleagues, is to glimpse a world of art in radical transition and a world of art criticism increasingly fractured and pulled apart by a new generation of professional art critics.[1]

As Victorian artists increasingly discounted narrative, human experience, pictorial space, and social proprieties in their works, Monkhouse was forced to refashion his most fundamental convictions. He had long held that “beauty,” “sincerity,” and “truth” determined worthiness and governed morality in art. His faith in this triumvirate guided his criticism, until cumulative reverberations from works by Edgar Degas, Albert Moore, Edward Burne-Jones, and Whistler sheared it apart, piece by piece.

But moral touchstones are not easily dislodged. They are less easily replaced. For years, Monkhouse railed against the “worship of the ugly” and those artists who violated his cherished principles with impunity. Even as he welcomed the trajectory that enabled the “gradual emancipation from everything which could trammel the personal will of the painter,” he loathed the excess that often characterized its leading edge. He had little forbearance for artists, regardless of reputation, who covered the canvas “with a slovenly mess of strokes and streaks, smears and splashes, the intention of which is only to be realized at a distance, which too frequently adds little enchantment to the view.”[2]

Passages like this—and there are several—prompt a long sigh from the modern reader and lead to a quick dismissal of Monkhouse as stodgy, reactionary, hostile to Aestheticism and Impressionism, or indifferent to the attractions of the sensationally new, mostly French, art that streamed into London toward the end of the nineteenth century. It would seem that Monkhouse falls squarely into the usual assessment of Victorian art critics: cautious philistines, intellectually hidebound, whose writings are about as stimulating and varied as paging through an album of pressed ferns.

Viewed from a broader perspective, Monkhouse’s books and articles reveal the evolution of an art critic who earnestly sought to make sense of the bewildering aesthetic crosscurrents of the late nineteenth century. In this 1884 excerpt from the Academy, Monkhouse’s instructions to art students double as a sympathetic guide for confused critics:

The question, “What is art?” was never so difficult to answer, and was never so urged upon the student. It is impossible for him to ignore the many different answers which have already been given by different schools, or to pin his whole faith to one of them. Unless he would be behind his time, he must weigh them all. But he must see that he gets the true versions, and this cannot be learnt from a mere examination of the works themselves, and a study of their technique. Personal predilection and prejudices must be set aside, purely professional scrutiny must be supplemented by historical study, before he learns the secrets of their genesis and is able to translate their message.[3]

Monkhouse understood that the answer to his question was far from settled; to the contrary, his contemporaries were awash in competing aesthetic theories. The passage further suggests that Monkhouse recognized a professional imperative to step away from the comfort of his convictions in order to weigh opposing points of view, to bridge seemingly irreconcilable arguments about the nature and function of art. His writings reveal that he was keenly aware of what Elizabeth Prettejohn described as the “general division between those who advocated an art of pure formal perfection and those who wanted an art fully engaged with the human passions.”[4] He was a transitional figure, a quintessential Victorian man-of-letters whose work spanned the “gap” between the conventional and the “new” art criticism.

A Trustworthy Guide

Though Monkhouse never fully embraced the formalist arguments of the “New Critics” like R. A. M. Stevenson (1847–1900) and D. S. MacColl (1859–1948), he eventually met them more than half-way. But to evolve gracefully and convincingly from the precepts of Ruskin to the principles of modernism was no mean feat. To the end, Monkhouse subscribed to the Ruskinian doctrine that the highest purpose of art was to elevate the mind, to promote the public good. This point of view is most evident in Monkhouse’s many laudatory monographs on British painters and art collectors. He was a master of the serialized biographies that, as Julie Codell has so thoroughly explored, erased degenerate stereotypes of artists, raised their professional status, mediated their economic interests, bolstered their commercial success, and cast them as national cultural heroes.[5] Not coincidentally, in this Academy excerpt of 1886, Monkhouse recognized that the publishing enterprise that created the cult of the artist also elevated the status of the art critic:

It is much the same in other countries, for throughout Europe the attitude of the critic has changed. He is no longer a cold judge, measuring works of art by abstract principles and an arbitrary ideal; but an interpreter, historical and biographical, seeking the man in his work, and the mind of him as affected by the outside influences of his life. Viewed as documents in the social and intellectual history of the world, and as expressions of individual character, pictures have revealed a wealth of human interest which was unthought of before.[6]

As Monkhouse aggrandized the role of the critic in this 1886 article, he also carved out some much-needed room for theoretical maneuvering, which he was beginning to need. Only a few months earlier, in the Magazine of Art, he addressed at length audiences confounded by Albert Moore’s (1841–93) paintings. He vigorously defended Moore against charges that works such as Yellow Marguerites (1881) and A Quartet; A Painter’s Tribute to the Art of Music, A.D. 1868 (1868; fig. 2) were “merely decorative,” had “no ‘subject’ to speak of,” and tried “to be classical” and failed. Moore, Monkhouse states plainly, is “no Alma Tadema seeking to reproduce for us the life of extinct civilisations. . . . To complain of him for not being ancient Greek when he only wishes to be English of the Nineteenth Century would be as wise as to complain of a pear-tree for not producing peaches.”[7] Regarding the lack of subject, Monkhouse waves it away as he also dismisses the necessity for narrative, chronological, or geographical plausibility, connection with legend or history, literature, fact-based imaginings of the past or dreams of the future. To the complaint that Moore’s work lacks emotion, Monkhouse responds that to introduce it would have disturbed or obliterated the artist’s “beautiful combinations of form and colour.”[8] Deciphering Moore’s choices, principles, and motivations, Monkhouse shifts the debate from the subject of Moore’s paintings to the individuality of the artist’s visual expression and its effect on the viewer:

Albert Moore (like Whistler) is one of the most consistent and purest examples of an artist “for art’s sake.” This much-abused phrase has at least one clear and rational meaning, notwithstanding its mysterious tautology. . . . That sense which I have spoken of as a rational one means art regarded as a special means of expression, conveying sensations which can be precisely and directly conveyed in no other way. Like music, painting is an art which appeals immediately to one sense only. As the ear to music, so the eye to art is the only aditum or means of communication to the intellect, the emotions, and the other senses. In proportion to the force with which this fundamental idea actuates a painter, his pictures will be independent of what is usually called “subject,” or, in other words, his subjects will become more and more disconnected with sensations which are not the immediate result of sight.[9]

In this article Monkhouse asserted that art’s first function is to be “attractive,” to “convey a pleasure,” that is, “the pleasure of seeing.” In Moore’s work that pleasure derives from the viewer’s experience of ideal beauty, a beauty not arising from content but from form and arrangement. What Monkhouse found compelling was not so much that Moore painted “beautiful things,” but rather that

he painted them in a particular way, not in their chance combination, not with any strife to fix that poetry of accident of which Whistler is such a master, but with care and design aforethought, arranging them so that the outcome of his labour should be an organised whole in which the beauty of each thing should interweave with the beauty of every other thing, and the result should be a harmony of many beauties—a feast for the eyes as nearly faultless as human work can be.[10]

The pleasure of seeing, for Monkhouse the essential element of beauty, arose from the abstract formal harmonies of Moore’s paintings. In a world of art crowded with “overwhelming allusions and unbearable suggestiveness,” Monkhouse felt that the pure expression of Moore’s idea, “self-sufficient and precisely wrought,” was a remarkable achievement.[11]

Prompted perhaps by his love of French poetry, perhaps by his American editor, and certainly by the provocative and controversial paintings of Moore, Edgar Degas, and James McNeill Whistler, in the coming years Monkhouse was to embrace the language of Aestheticism and the tentative formulations of modernist criticism. But no treatise announced this shift; his efforts in this direction were subtle and sporadic, never addressed systematically or coherently. In lieu of formulating a penetrating, comprehensive analysis he simply cobbled his views piecemeal, a paragraph here and a paragraph there.

Monkhouse may have been more cautious than conservative, unwilling to jeopardize his wide reputation as the general public’s trustworthy guide to the visual arts, a reputation also recognized by some of the most influential editors of the day. He was admired by Sidney Lee (1859–1926), the editor of the Dictionary of National Biography, for the thoroughness of his research; by the editors of the Magazine of Art, W. E. Henley (1849–1903) and his successor Marion Harry Spielmann (1858–1948), for his well-penned critical insights; and by Edward L. Burlingame (1848–1922), editor of Scribner’s Magazine, who placed Monkhouse at the fore of contemporary authors on the fine arts.[12]

These editors, of fairly conservative publications, were among a confluence of forces that shaped Monkhouse’s opinions and how he presented them to the public. Like many intellectually versatile Victorians, Monkhouse was accomplished in a number of fields. Despite his well-received art criticism, his expertise as a connoisseur of paintings and china, and a forty-odd year administrative career at the Board of Trade, Monkhouse in his own mind was always first a poet, an enthusiasm he shared with fellow Board of Trade clerks, poet Henry Austin Dobson (1840–1921) and author Edmund Gosse (1849–1928). During breaks, lines and snippets flew up the stairs and across the corridors, hastily scratched on Board of Trade letterhead.[13] The trio’s youthful devotion to the revival of French poetic forms was closely linked with France’s emerging Aesthetic Movement of the 1860s, an early introduction to l’art pour l’art that likely influenced Monkhouse’s later embrace of the Aestheticism of Moore and Whistler.

Littérateur, cultural critic, and close friend Edmund Gosse never found much to praise in Monkhouse’s poetry, but found much to admire in the man and the critic. In “Cosmo Monkhouse as an Art Critic,” published after Monkhouse’s death in 1901, Gosse remembered his old friend eyeing some collector’s prize:

His manner in front of a picture, or a vase, or a medallion, was simplicity itself. . . . He bent his eye very seriously to the task, and often it was the eye alone which seemed to move. Stolidly, almost torpidly, Monkhouse would fix himself in front of the object and then turn and some little word muttered, or almost grunted, which gave the key to the position. . . .

Monkhouse’s gracious heart shrank from the knitted brow and pursed lips of the disappointed owner, and he cultivated little shrugs and coughs that let the poor man down lightly, vague exclamations and wanderings of voice that broke his fall. Then he would trot, as soon as possible, to a station in front of something that he could really praise, and the difference of emphasis did more than direct exposure could have done to shake confidence in a fraud or a copy.[14]

The Ground Shifts

As connoisseur or critic, the gracious Monkhouse was always concerned with genuineness, or as he termed it, “sincerity,” a sweeping term that he (and his contemporaries) used liberally to encompass the intentions, the earnestness, and the industry of the artist. He wrote of this quality as “a sincere desire to follow a cherished ideal,” “the cause of genuine emotion,” and artists “giving us of their very best.”[15] Sincerity implied honesty of mind and purity of intention, conception, and sentiment; it eschewed affectation and exaggerated effects that sloshed over into sentimentality. For most critics of Monkhouse’s generation, it was at the heart of morality in art.

In keeping with the attitudes of many of his contemporaries, sincerity was invariably linked to the word “beauty,” and “beauty” to “truth”—potent code words that, in combination, encompassed a universe of Victorian ideals: the virtues of manliness, domesticity, belief in progress, a rigorous work ethic, self-sacrifice for the public good, and inherent moral decency. For Monkhouse, the measure of any painting’s greatness was the extent to which it was imbued with sincerity and beauty as demonstrated in the skills employed in its conception, composition, and finish, in the moral truths that it contained and conveyed, in the harmony of its color, and in the comprehensibility of its subject and message.

Over time, Monkhouse began to reassess these defining elements. Sincerity remained pivotal but his definition of it expanded and evolved, turning less on respect for precedent and industry and more on individuality and self-expression. Beauty and truth became less dependent on—in Monkhouse’s words, “disconnected from”—subject and more related to what he called “sensations” conveyed through the eye to “the intellect, the emotions, and the other senses.” In exercising his faculties to create these sensations, the artist was “to be bound by no convention, to be biased by no fashion, to keep his mind perpetually free to genuine sensations of beauty from any source.”[16]

However, Monkhouse does not consistently sustain this point of view, as if he had not fully realized its ramifications. For the balance of the 1880s, Monkhouse wrestled with the notions of sincerity and beauty and the relative importance of content and form. But by the mid-nineties the critic had moved beyond subject and narrative in his search for sincerity. This evolution can be seen by comparing two “before and after” examples of Monkhouse’s reviews of Edward Burne-Jones’s (1833–98) Perseus series.[17]

The first excerpt concerning the series is from an 1888 issue of the Academy and the second from a Scribner’s Magazine article of 1894. On exhibit at the New Gallery in June of 1888 were three Burne-Jones works relating to the story of Perseus: Danaë (The Tower of Brass), The Rock of Doom, and The Doom Fulfilled. Taking first The Tower of Brass, Monkhouse wrote in his rich, occasionally florid, style about beauty, composition, and finish:

Danae watches with wonder the building of the brazen tower in which she is to be immured for the safety of her father. Robed in brilliant red, she stands in a garden, her slender figure relieved against a cypress-like shrub, her feet surrounded with deep blue iris blossoms. She looks through an archway with a heavy bronze door, which opens on the space where the tower is being built and plated with sheets of brass. The arrangement of colours is striking, beautiful, and harmonious; the painting throughout is most careful and accomplished. . . . It is a masterly and beautiful picture, such as only a true artist-poet could have designed.[18]

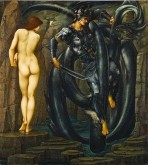

Thus Monkhouse established the overall subject as appropriate for contemplation, made worthy as the noble expression of “a true artist-poet.” But even though the fundamental elements of beauty had been satisfied, Monkhouse required them to be amplified by an underlying nobility of purpose, a grand motivation, or the revelation of a subtle truth—some kind of moral energy aimed at securing the viewer’s spiritual participation. Monkhouse had no trouble locating this moral current in the manly Perseus, flying by on his winged sandals in The Rock of Doom or battling with a loathsome sea monster in The Doom Fulfilled (fig. 3). The 1888 review continued:

It would be easy enough to admire only, if we regarded these compositions as purely decorative, mere arrangements of form and colour suggested by the story; but the artist will not allow us to do this. He appeals to our emotions. The pictures are intended to be a power to the soul as well as a pleasure to the eyes.[19]

Burne-Jones has offered beauty and uplifting morality, but their combined power is hindered by the comprehensibility of the subject. For Monkhouse, this comprehensibility, hence the success of the series, is seriously jeopardized by the sea monster.

In The Doom Fulfilled, Perseus, in full body-hugging armor, is about to be constricted by a gargantuan sea serpent. Surprisingly, Monkhouse does not ground his objection in the possibility that the audience might find this situation too far removed from the late nineteenth-century horrors of their own experience, or to the fact that this extraordinary scene could never really happen. His objection is that it could never happen in this way.

That is, he objects to how Burne-Jones has realized the narrative. Monkhouse complained that the sea monster, “something like a huge eel with the head something like a salmon” is not behaving monsterly enough; “he coils himself in a way no eel or even serpent ever did. . . . He is invertebrate and rigid, a masterpiece of metal-work perhaps, but incapable of motion.”[20]

Then he cites the cumulative problems of Perseus floating rather than flying, his body-hugging armor too weighty for credibility, and the demure Andromeda looking wholly unperturbed. As Monkhouse puts it:

Then we know what fighting is, and these terrible combatants are not fighting: the sword hangs idle in an idle hand, the monster lets the hero’s legs between his coils without crushing them. This is, perhaps, because Perseus is invisible; but if so, why do they stare at one another? . . . Then we know what armour is, and enough about flying to make the heavy suit that Perseus wears an additional tax on our faith. . . . Finally, we know what human nature is, and it is difficult to believe in the terror of a scene which can be regarded by Andromeda with such sang froid. Both pictures are full of beauty. The figure of Andromeda is exquisite, the composition especially of that in which Perseus is fighting the monster is admirable and original, the execution is broad and masterly; and if we can only look upon Andromeda as on some mystic medieval Alice in Wonderland, there would be little room for criticism.[21]

In this case, it is not the artist but the critic who taxes our faith. Would a battered, bruised, filthy, and cowering Andromeda impart a searing reality to the confrontation? Would a more flimsy suit of armor make a flying Perseus more credible? Monkhouse implies that Burne-Jones, “who cared nothing for possibilities,” should have taken note of British painter Arthur Lemon’s (1850–1912) adroit handling of centaur life, in which the “difficulty of realising a ‘mixtum genus, prolesque biformis’ has never perhaps been so faced and mastered before.”[22] This astonishing literalness can best be labeled early- to mid-Monkhousian; it testifies to the extraordinary tenacity of conventional modes of visual interpretation. Instead, confounding Monkhouse, Burne-Jones obstinately stuck to his own fantasies which were inhabited by nude maidens not even slightly intimidated by sea monsters and mythical heroes who could fly despite the most cumbersome body armor.

Six years later, in an 1894 article on Burne-Jones for Scribner’s Magazine, Monkhouse wrote about the same paintings, but by then he had shifted his focus from the sea monster’s shortcomings to the broader issues of artistic imagination and expression. The very elements that were most wrong were now most right. The “mere arrangements of form and colour” that he had dismissed six years earlier were now at the fore, along with the discordant visual tempo of the painting, the result of Burne-Jones’s active imagination cavorting freely with, and often subverting, common experiences of time and space:

In these pictures one is perhaps more struck than usual by the deliberately decorative character of the work, and the stillness of a visionary world in which the fiercest conflicts happen, as it were, to slow music.[23]

Burne-Jones’s fantastic, melancholy imagery now passes muster as truth, but under a different rationale: not because it corresponds with the Greek myth or the William Morris text or with human experience, but because it is in honest alliance with the artistic imagination. Monkhouse wrote:

Where does the great principle of sincerity come in here? The answer is comparatively easy—be sincere to your imagination, realize as far as possible the vision of your mind, careful that your design is the expression of your true self, not an imitation of what someone else has done, or what you think he would have done in your place. In imaginative art such sincerity is the only way to salvation, and Burne-Jones found it.[24]

But if, between 1888 and 1894, Monkhouse had resolved his dilemmas with Burne-Jones’s work by subordinating narrative and by broadening his definition of sincerity to include greater freedom of imagination and expression, he had yet to embrace the full implications of that position. He was not about to release artistic expression from its traditional ties to moral responsibility.

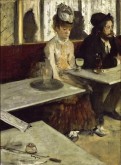

The L’Absinthe Debate: Straddling the Divide

However, during the months that he was preparing his article on Burne-Jones, Monkhouse was strongly prodded in that uncomfortable direction by a debate that was raging in London, of a kind not seen since the 1878 Whistler-Ruskin trial. This galvanizing event was the Grafton Gallery’s 1893 exhibition of Edgar Degas’s (1834–1917) L’Absinthe (fig. 4), which had drawn loud hisses from the bidding audience when it came to the auctioneer’s block in a London salesroom the year before. Of course, this was not a new painting. In fact, it had been exhibited in 1876 by Charles Deschamps in his New Bond Street gallery, and later that year in Brighton under the title A Sketch in a French Café.[25]

A number of critics perceived L’Absinthe as an affront to public morals typical of the outrageous Degas, an affront that made the provocative postures of “ballet girls” seem tame by comparison. In the February 25, 1893 number of the Speaker, George Moore (1852–1933) offered a creative backstory for the subject:

The woman that sits beside the artist was at the Elysée Montmartre until two in the morning. . . . She did not get up until half-past eleven; then she tied a few soiled petticoats round her, slipped on that peignoir, thrust her feet into those loose morning shoes, and came down to the café to have an absinthe before breakfast. Heavens!−what a slut![26]

It was an influential interpretation. Three years later, in 1896, the Times reviewer must have shuddered when he wrote of another Degas work: “The admirers of the most modern ways in art will be enthusiastic about ‘Le Pédicure,’ by Degas, where extraordinary mastery of colour and expression are put at the service of a subject barely within the limits of the permissible.”[27]

Even though Impressionist painting had long ceased to be a novelty in 1890s London, the questions that it prompted—not those of technique, naturalism, optical distortions, flatness, or finish—but questions of artistic responsibility and appropriate subject matter, and their relation to public morality, were by no means settled. If you were a London art critic in 1893, L’Absinthe was the proverbial “elephant in the parlor” that provoked an unavoidable choice. Should you side with the upholders of the traditional English school, the defenders of narrative painting, the adherents of the no-longer-infallible but still noble Ruskinians (that is, with the “Philistines,” a label appended by journalist John Alfred Spender)? Or, should you throw your lot in with the New Critics D. S. MacColl, Walter Sickert, R. A. M. Stevenson and others, whose challenge to quash sentiment, to redefine beauty and artistic responsibility was put forward by MacColl with these words:

But L’Absinthe, by Degas, is the inexhaustible picture, the one that draws you back, and back again. . . . M. Degas understands his people absolutely; there is no false note of an imposed and blundering sentiment, but exactly as a man with a just eye and comprehending mind and power of speech could set up that scene for us in the fit words, whose mysterious relations of idea and sound should affect us as beauty, so does this master of character, of form, of colour, watch till the café table tops and the mirror, and the water-bottle and the drinks and the features yield up to him their mysterious affecting note.[28]

Confronted with what Kate Flint has called the central critical question of the period, style versus subject, Monkhouse straddled the divide between the conservatives and the new generation of critics.[29] Considering works such as L’Absinthe, on the one hand he declared that the history of Western painting has been “one of the gradual emancipation from everything which could trammel the personal will of the painter.” Yet, on the other hand, he tempered it by adding, “But is in vain to assert, as is the fashion, that such liberty brings with it no responsibilities.”[30] Monkhouse proclaimed Degas an artist of “exceptional gifts,” who had done his utmost “to destroy stale conventions, to lop off boughs of false sentiment, and to make the language of painting pure and strong.” He cited Degas as one of the “prophets of what may be called the new gospel of paint.” But he could not admire Degas’s portrayal of, in his words, “the victims of absinthe.”[31] Without a beauty Monkhouse could appreciate or a morality he could sanction, he found the gospel hollow.

Monkhouse’s stance on subject and unrelenting demand for beauty opened a breach not just with Degas and MacColl, but also with the evolving status of the artist at the end of the nineteenth century. It was a dilemma that Monkhouse must have recognized and carefully pondered, because in his last major publication on English artists, in 1899, he tried to bridge the gap.

To do so, surprisingly, he turned to the work of the contentious James McNeill Whistler, about whom he had not written much for ten years. When he had addressed Whistler, his comments were usually cast in halftones of admiration—for Whistler’s handling of paint and composition—and regret, for what he termed “the faintness of its human note.”[32] Yet his remarks invariably intimated that the work would outlive the man:

His work has for many years run the gauntlet of derision and caricature; but he has refused to change, laughing with those who took him as a jest, but ever serious with himself. He is still easy to laugh at, still easy to imitate up to a certain point; but the number is daily increasing of those who detect in his work much which cannot be laughed out of court, and which even the most skilful plagiarist cannot catch. At Messrs. Dowdeswell’s this year, he is wholly himself; in water-colour and pastel inimitable, in oil sometimes exquisite—in everything (pencil scraps included) the distinct Whistler, the master of pictorial shorthand, the poet of accident, the prophet of the not-too-much.[33]

Where others saw only “a saucy hussy” in Whistler’s “Note in Flesh Color and Red,” on exhibit at Dowdeswell’s in May 1886, Monkhouse celebrated the artist’s “faultless taste” of color and “perfection” of tone. But even as he applauded Whistler’s ability to paint what others thought unworthy or impossible, to carry “his divining rod into the slums,” to rescue “jewels from the gutter,” to seize pleasures “beyond the art of words to describe,” Monkhouse withheld his unreserved endorsement. Offhandedly, he termed Whistler’s smaller works, mostly watercolors and pastels, as delightfully restorative little “bits,” the “oysters and Chablis” of art. Whistler may have pried loose Monkhouse’s hold on subject, but the critic was hardly prepared to expound in print on the value of “accident” or define the implications of the “not-too-much.”[34]

Nonetheless, the idea of Whistler as master, poet, and prophet lingered in Monkhouse’s imagination. Approving of Frederick Wedmore’s 1886 study and catalogue, Whistler’s Etchings, Monkhouse wrote in the February 1887 number of the Academy:

He rightly insists on the deliberate and consistent manner in which the artist has cut himself adrift from associations of literature and history, from commonplace sentiment, from conventional methods, and has made his work the unique expression of a unique personality. Skill apart—and at least in etching no one will deny that it is exceptional—Mr. Whistler’s art is the man, with all his gifts and all his defects, and it is just because it is so that it is of permanent—no one can say how permanent—interest. Strange as the opinion may appear to those who look upon Mr. Whistler as only an artistic jester—one constant quality in his work is sincerity and another is simplicity; and these qualities give long life to works of art.[35]

From Watts to Whistler

Whistler does not resurface in Monkhouse’s writings until 1899, when the author was commissioned by New York publisher Charles Scribner’s Sons to assimilate his “pocket biographies” into one volume, British Contemporary Artists. From 1894 to 1897, Scribner’s Magazine had published Monkhouse’s series on leading British artists. The subjects were selected by the author: “Edward Burne-Jones”; “George Frederick Watts, R.A.”; “Laurens Alma-Tadema, R.A.”; “Lord Leighton”; “Sir John Millais, Bart., P.R.A”; “William Quiller Orchardson, R.A.”; and “Sir Edward J. Poynter, P.R.A.” In articles of about twenty pages that Scribner’s Magazine editor Edward Burlingame called “models of their kind,” Monkhouse defined for Americans a distinctively English world of art based on timeless aesthetic principles, noble aspirations, open inquiry, and hard work.[36] He found its purest exemplar in one of the subjects of his series, G. F. Watts, whom Monkhouse called “a painter of ideas, of the properties and attributes of the human race, of the forces which surround and mould the lives of men, of the dreams and aspirations of the world—a painter of spiritual motive power.”[37] In writing about Watts and the other artists that Monkhouse called “these men of genius,”[38] he was part of the much larger enterprise of establishing British artists as symbols of the empire, embodiments of British morals and values. According to Julie Codell, “what made artists worthy of biographical scrutiny was their material and social success, but what made them worthy of becoming cultural icons was a belief that they were motivated purely by Victorian ideals—moral purpose, beauty, faith, and nationalism.”[39] Critics therefore chose and wrote about their subjects carefully, for in late Victorian Britain the artist had not yet achieved the “outsider status” that was to evolve more fully in the early twentieth century.

Yet by the late 1890s Monkhouse was ready to discard, or at least to circumvent, the notion of the artist as national archetype. The subject of the final installment for his Scribner’s Magazine series was to be James Whistler, infamous for his defiance, a “volatile and irresponsible” personage whose idea of work was to knock off a nocturne in a couple of days (fig. 5).[40] American by birth, Whistler hardly fit the public persona of the English gentleman-artist—diligent, earnest, and productive—that Monkhouse so admired and over decades helped to craft in print for dozens of Victorian artists. In 1884, when Whistler was accepted into the Society of British Artists, the Times wrote: “Artistic society was startled by the news that this most wayward, most un-English of painters had found a home among the men of Suffolk Street, of all people in the world.”[41] If by the nineties Whistler had ceded the lance-point of the avant-garde, his paintings were still mocked as much as they were admired. However, this apparently had little effect on Monkhouse by the end of his career.

Taking a position at odds with his own precedent, Monkhouse set about fitting the American-born Whistler into the framework of the English school of painting. If it seems twenty years too late, it is worthwhile to consider MacColl’s observation, from the vantage point of the early 1930s, that “The first task for a critic in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries was to champion some of the senior artists still in dispute, Manet, Degas, Whistler, Rodin, the Impressionists, and others.”[42] To MacColl, Monkhouse was arguably right on time.

Still, Whistler proved to be an unwieldy capstone. Monkhouse, who was acquainted with Whistler, warned American editor Edward Burlingame that the artist was “a difficult person to write about & a difficult person to deal with,” “here today & gone tomorrow.”[43] Months of transatlantic discussion ensued, with Burlingame confirming that Whistler “has always been reported a particularly difficult man to deal with, and several instances that I have heard of certainly confirm this idea.”[44] No doubt Monkhouse was wary of the unpredictable fits of pique that might jeopardize months of work and imperil stringent deadlines. Ultimately, the plans for a feature article collapsed, with Monkhouse writing to his editor in exasperation, “I do not despair but as yet circumstances have not helped me, & it would I think be no use to try to ‘rush’ him.”[45]

However, Monkhouse’s determination to position Whistler among the more exalted British artists, the “men of genius,” held fast. In his last significant publication, British Contemporary Artists, Monkhouse paid homage to Whistler and the sweeping changes that he inaugurated:

One of the most distinguished and original of modern artists has done his best to show by practice and precept that art is and should be independent of all things except itself—even of humanity, except such as is contained in the purely artistic personality of the artist himself.

Recognizing that he needed to explain further, Monkhouse continued:

I have dwelt more particularly upon Whistler’s art, not only on account of its special beauty, but because, of all masters of the more “advanced” schools, he has had the greatest influence upon British art. He belongs to what for want of a better term may be called the “artistic” side of art, like Manet, Degas, and Claude Monet. To the teaching and example of these and many others (mostly Frenchman) the British school of the present day owes much. They have furthered greatly the emancipation of artists from the fetters of tradition, have helped them to see with their own eyes and speak with their own voice.[46]

It is an unexpected admission from one still wary of the “faintness” of the “human note” in Whistler’s paintings. Monkhouse was not prepared to go as far as Walter Sickert (1860–1942) in calling Whistler “immortal a thousand times over,”[47] but he finally found common ground with fellow critic MacColl, the tireless defender of Impressionism, who thought Whistler an artist of “rare genius.”[48] By the end of the century, the criteria that Monkhouse had once used to measure the value of a painting—narrative, subject, technical skill, draftsmanship, power of design, human sentiment, worthiness of the artist’s personal character—had been distilled to individualism and beauty.

As the fin-de-siècle emancipation of the artist felled Monkhouse’s long-held tenets one by one, he found the intersection of beauty, individuality, and vision increasingly hard to locate:

It may seem to some a little surprising that this use of art for the expression of the most exalted human sentiment should have occurred simultaneously with other movements of an almost opposite character; but the art of the latter half of the nineteenth century is distinguished by diversity of all kinds. It has thrust forth feelers in every direction and reached nearly all extremes. A hundred theories as to the true functions and limits of art have been broached and followed by a devoted band, until the sects of art are almost as many as those of religion.[49]

The clubby Victorian world of art and art criticism was changing at a dizzying pace, splintering in untold new directions. Reliably cautious, Monkhouse did not lead the change, but he was certainly a part of it. For, as he considered Whistler and other proponents of (what he called) “the more ‘advanced’ schools,” he released the English artist from the confines of the national hero and shifted the emphasis of his own discussions from content and narrative to tone, form, and individual expression.

Along with Stevenson, Moore, the younger and more emphatic MacColl, Sickert, and others, Cosmo Monkhouse reshaped the language of British art criticism. He was a transitional figure, most comfortable with a conservative point of view but not cemented to it. Far from shying away from the new, he believed that controversy helped art thrive. Taking heart from the diversity and vibrancy of late Victorian critical opinions on art, Monkhouse observed, “This is good for art as one section counteracts the extravagances of the other, and it is good for humanity also, as it gives them both a Watts and a Whistler.”[50]

[1] Cosmo Monkhouse, British Contemporary Artists (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons; London: William Heinemann, 1899); and Cosmo Monkhouse, Masterpieces of English Art (London: Bell and Daldy, 1869). Following his own apparent preferences, citations to this author will omit his first name, William.

[2] Cosmo Monkhouse, “The Worship of the Ugly,” National Review 157 (March 1896): 131.

[3] Cosmo Monkhouse, “Fine Art,” Academy, August 16, 1884, 111.

[4] Elizabeth Prettejohn, Art for Art’s Sake: Aestheticism in Victorian Painting (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007), 188.

[5] Julie F. Codell, “Artists’ Biographies and the Anxieties of National Culture,” Victorian Review 27, no. 1 (Winter 2001): 1–35; and Julie F. Codell, Artists’ Life Writings in Britain, c. 1870–1910 (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[6] Cosmo Monkhouse, “Fine Art,” Academy, October 9, 1886, 248. Monkhouse published over three dozen articles for the Academy (1869–1916), a weekly that the Manchester City News called “informative, incisive, and trustworthy” and acknowledged as “the first place among literary journals as the representative of the ripest and soundest English scholarship,” Academy, March 14, 1874, iii. The periodical’s reputation for intellectual vigor lasted well into the 1890s. See generally, John Curtis Johnson, “The Academy, 1869–96: Center of Informed Critical Opinion” (PhD diss., Northwestern University, 1958); and “The Academy,” in Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction, ed. John Sutherland (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1898).

[7] Cosmo Monkhouse, “Albert Moore,” Magazine of Art 8 (1885): 194–95.

[8] Ibid., 195.

[9] Ibid., 194. However, Monkhouse did not apply this expansive rationale to all innovative practices. For example, in another article of that same year, he pronounced Alma-Tadema’s boldly cropped portrait of his brother-in-law, Dr. Washington Epps, “eccentric” and “unpleasant”: “Mr. Alma Tadema’s freaks in segmental composition have never resulted in anything more unexpected than this rufons [sic] head of a doctor staring against a section of white bed containing fragments of a patient.” Monkhouse, “The Grosvenor Gallery,” Academy, May 2, 1885, 318.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Burlingame, perhaps the foremost American editor of his day, was particularly taken with Monkhouse’s artists’ biographies, which he called “models of their kind.” Edward L. Burlingame to Cosmo Monkhouse, January 22, 1897, Edward L. Burlingame Letterbook 18, p. 698, Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library. Commenting on the 137 entries on artists that Monkhouse authored for the Dictionary of National Biography, editor Sidney Lee stated that “These articles supply a vast amount of information in a small space, and illustrate his power of combining complete records of fact with critical appreciation of artistic achievement.” Lee added, “Their subjects covered the whole field of English art. In all regards Monkhouse proved himself an ideal contributor. He spared himself no trouble in collecting and testing his information.” Sidney Lee, “Cosmo Monkhouse,” Athenaeum, July 27, 1901, 125.

[13] Several examples of this youthful verse survive in the W. Cosmo (William Cosmo) Monkhouse Collection, Manuscript Collection MS-2876, Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

[14] Edmund Gosse, “Cosmo Monkhouse as an Art Critic,” Art Journal, n.s. 64 (March 1902): 73.

[15] Monkhouse, “Grosvenor Gallery,” 318.

[16] Monkhouse, “Albert Moore,” 195.

[17] The Perseus series was commissioned in 1875 by statesman and arts patron Arthur Balfour for his London home. Only four paintings were completed, now in the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart.

[18] Cosmo Monkhouse, “Fine Art. The New Gallery,” Academy, June 2, 1888, 383.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Cosmo Monkhouse, “The New Gallery,” Academy, June 16, 1888, 419–20, referring to Lemon’s two images of centaur life, A Vendetta and A Struggle, among the paintings exhibited with Burne-Jones’s Perseus series.

[23] Cosmo Monkhouse, “Edward Burne-Jones,” Scribner’s Magazine, February 1894, 145.

[24] Ibid., 138.

[25] Kimberley Morse-Jones, “The ‘Philistine’ and the New Art Critic: A New Perspective on the Debate about Degas’s ‘L’Absinthe’ of 1893,” British Art Journal 9, no. 2 (Autumn 2008): 50–61, at 52.

[26] G[eorge] M[oore], “The Grafton Gallery,” Speaker, February 25, 1893, 215–217, at 216, Google Books, accessed May 20, 2015, https://books.google.com/books?id=nolNAAAAYAAJ.

[27] “Art Exhibitions,” Times (London), February 15, 1896, 9, The Times Digital Archive (1785–2009), accessed April 20, 2015, Gale Cengage Learning, http://www.gale.cengage.com.

[28] D. S. M. [Dugald S. MacColl], “Art. The Grafton Gallery,” Spectator, February 25, 1893, 256.

[29] Kate Flint, “The ‘Philistine’ and the New Art Critic: J. A. Spender and D. S. MacColl’s Debate of 1893,” Victorian Periodicals Review 21, no. 1 (Spring 1988): 3–8.

[30] Monkhouse, “Worship of the Ugly,” 126.

[31] Ibid., 129.

[32] Monkhouse, British Contemporary Artists, xii.

[33] Cosmo Monkhouse, “Brown and Gold,” Academy, May 22, 1886, 369–70.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Cosmo Monkhouse, “Fine Art,” Academy, February 19, 1887, 136.

[36] Burlingame to Monkhouse, January 22, 1897.

[37] Monkhouse, British Contemporary Artists, 22.

[38] Cosmo Monkhouse to Edward L. Burlingame, April 3, 1894, Author Files I, CO101, Box 104, Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons (Scribner Archives), Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University.

[39] Julie F. Codell, “Serialized Artists’ Biographies: A Culture Industry in Late Victorian Britain,” Book History 3, no. 1 (2000): 94–124, at 95, Project Muse, accessed April 20, 2015, https://muse.jhu.edu.

[40] Whistler’s The Gentle Art of Making Enemies was reviewed in “Books of the Week,” Times (London), June 19, 1890, 10.

[41] Elizabeth R. Pennell and Joseph Pennell, The Life of James McNeill Whistler (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1911; London: William Heinemann, 1911), 249, citing “The Society of British Artists,” Times (London) December 3, 1884, 3.

[42] D[ugald] S. MacColl, Confessions of a Keeper (London: Alexander Maclehose and Company, 1931), v-vi.

[43] Cosmo Monkhouse to Edward Burlingame, December 9, 1897, Author Files I, CO101, Box 104, Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

[44] Edward L. Burlingame to Cosmo Monkhouse, February 26, 1897, Edward L. Burlingame Letterbook 18, p. 734, Archives of Charles Scribner’s Sons, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

[45] Monkhouse to Burlingame, December 9, 1897.

[46] Monkhouse, British Contemporary Artists, xi.

[47] Walter Sickert, “Whistler To-Day,” Fortnightly Review, April 1892, 547.

[48] D[ugald] S. MacColl, “A Debt,” Saturday Review, July 25, 1903, 106.

[49] Monkhouse, British Contemporary Artists, x.

[50] Ibid., xii.