The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Railroad magnate William Henry Vanderbilt’s (1821–85) art collection occupies an important place in the history of collecting in the United States.[1] His collection, housed in his personal art gallery at 640 Fifth Avenue, was more accessible than any other private collection in the early postbellum era and offered to New Yorkers a rare opportunity to acquaint themselves with contemporary European art. Moreover, his was the first major private art collection in New York City to be catalogued for its own sake rather than in conjunction with a special exhibition or auction sale. In addition to four small collection catalogs, he published a lavishly illustrated four-volume work, Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection, with text written by prominent art critic, Edward Strahan.[2] His collection catalogues and his accessible private art gallery provided a model for later collectors such as Henry Clay Frick, who once housed his burgeoning collection of old master paintings in Vanderbilt’s splendid art gallery.[3]

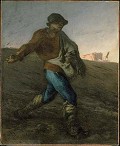

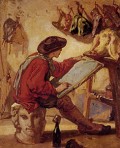

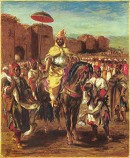

Vanderbilt formed his prodigious collection of over two hundred paintings by the foremost contemporary French, Belgian, German, Hungarian, English, Spanish, and Italian artists in less than four years (1878–82), astonishingly swift by any standard. Most of Vanderbilt’s pictures were genre, historical genre, literary, and history paintings. The remainder comprised orientalist, military, animal, and landscape pictures, with a single still-life and two religious subjects. His collection contained no pictures that would be deemed offensive—prurient subjects.[4] Among the works were John-François Millet’s canonical painting, The Sower (fig. 1), and important works by Thomas Couture (figs. 2, 3); J. M. W. Turner (figs. 4, 5); and Eugène Delacroix (fig. 6) at a time when few other collectors had acquired works by these artists.[5] In addition, he owned Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Louis XIV and the Grand Condé (fig. 7), Alphonse de Neuville’s Le Bourget (figs. 8, 9), Théodore Rousseau’s Gorges d’Apremont, and Sir John Everett Millais’s Bride of Lammermoor, all considered masterpieces in their time.

Though Vanderbilt intended his collection to remain intact at 640 Fifth Avenue in the Vanderbilt name, he could not have foreseen that future generations would fail to honor his wishes, or that his mansion would be demolished.[6] His wife inherited the collection, which, upon her death in 1896, passed to their fourth son and youngest child, George W. Vanderbilt, known for his lavish residence, Biltmore, in Asheville, North Carolina. After he died in 1914, the collection passed into the hands of George’s nephew, Brigadier General Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose widow, Grace Wilson Vanderbilt, sold the collection at auction before the mansion was razed to make way for commercial development.[7]

"Reconstructing" the Forgotten Collection

Although dispersed, Vanderbilt’s collection can be rather accurately reconstructed through Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection and his other collection catalogues, as well as through dealers’ diaries, letters, and auction catalogues.[8] Additionally, numerous contemporary accounts in periodicals such as the New York Times, Harper’s Weekly, and the leading journal devoted to collecting, the Collector, kept abreast of the art collection and discussed its contents.[9] Vanderbilt’s early biographer, journalist William Augustus Croffut, also wrote enthusiastically about the collection.[10] Regrettably, no private archive pertaining to his art collection exists.[11] He spent most of his life building his railroad fortune and only became a serious collector in the last eight years of his life.

Although the importance of Vanderbilt’s collection has been largely forgotten, contemporaries, such as prominent authority on art, Samuel Greene Wheeler Benjamin, recognized Vanderbilt’s gallery as the "finest gallery of art in America,"[12] and one which contained the "artistic landmarks of the world."[13] But by the turn of the century, surprisingly little had been written about the art collection of the wealthiest man of his time.[14] Writer August Jaccaci and American artist John La Farge intended to include Vanderbilt’s collection in their ambitious book project, Noteworthy Paintings in Private American Collections, but ultimately omitted it due to difficulties in obtaining photographs, and because they did not receive the revised essay they required before the publishing deadline.[15] American artist and critic Will Hicock Low, who wrote the essay, lauded the Vanderbilt collection as the most comprehensive, unique collection of modern pictures that comprised "the best work of his time."[16] However, recent accounts that acknowledge his cultural contribution have been limited largely to descriptions of his sumptuous mansion at 640 Fifth Avenue.[17] Wayne Craven, in his comprehensive book on Gilded Age architecture, devoted a chapter primarily to Vanderbilt’s lavish residence, but included only a cursory description of the art collection, embellished with anecdotal accounts from Towner and Varble’s Elegant Auctioneers of Vanderbilt’s encounters with artists Ernest Meissonier and Alexandre Cabanel.[18]

Unfortunately, Vanderbilt neither formed a private museum for his collection nor donated it en bloc to an institution. Instead, it remained in his family only briefly—having been dispersed at auction six decades after his death,[19]—rendering difficult its analysis today. This is, in part, why his collection has not received the scholarly attention it deserves. But it has also been overlooked because by the 1890s most of the artists represented in it had already become passé. Tastes had changed, and dealers and the market no longer favored academic art, which comprised most of Vanderbilt’s collection. The vogue for collecting old master paintings was fueled in part by growing wealth and increasingly image-conscious philanthropists.[20] Furthermore, Samuel P. Avery and George A. Lucas, Vanderbilt’s advisors, were no longer active in the art world.[21] The next generation of influential dealers such as Joseph Duveen and Charles Carstairs sold old master paintings, and advisors such as Bernard Berenson specialized in Italian Renaissance paintings. These men were among the experts who advised Isabella Stewart Gardner, Henry Walters, J. P. Morgan, Benjamin Altman, and Henry Clay Frick among others.

Documenting the Collection: The Catalogues

In addition to the collection itself, Vanderbilt’s catalogues, gallery, wealth, and altruistic intentions set him apart from other collectors.[22] Unlike them, Vanderbilt frequently published catalogues of his collection. These catalogues, printed in rapid succession between 1879 and 1886, helped acquaint art enthusiasts with his artworks. He published his first catalogue—the first in the United States to be published solely to document a private collection[23]—in 1879, just a year after an art-buying spree financed by a hundred- million-dollar inheritance.[24] Until then, catalogues were created only to accompany auction sales or special exhibitions, but Vanderbilt did not intend to sell his collection.[25] No catalogues were printed for the prominent collections of John Taylor Johnston or of Alexander T. Stewart until their auction sales.[26] And although William T. Walters had begun collecting European art before Vanderbilt, he did not publish his first collection catalogue until 1884, five years after Vanderbilt’s first catalogue.[27] Walters modeled his catalogue directly after Vanderbilt’s 1882 catalogue by cutting and pasting from it in order to fashion his own.[28] As a result, Walters’s catalogue was nearly identical to Vanderbilt’s in format.[29]

Vanderbilt’s small collection catalogues, all under 200 pages, unillustrated, and smaller than eight by five inches, mimicked the format of auction sale catalogues—such as the one published for John Taylor Johnston’s sale—which themselves imitated the catalogues of the Paris Salon.[30] Most entries comprised the artist’s credentials and the artwork’s title, dimensions, medium, and date. Several entries for pictures in his first catalogue extended to a page or more and included excerpts from artists’ letters to their patrons.[31] For example, the first catalogue included excerpts of letters for works by Jean-Léon Gérôme, Ernest Meissonier, Alexandre Cabanel, Raimundo Madrazo, Edouard Detaille, Louis Leloir, and Erskine Nicol.[32] These letters were reprinted in successive catalogues published in 1882, 1884, and 1886. Notably, these later catalogues reflect acquisitions of works by Ernest Meissonier, Jean-François Millet, J. M. W. Turner, Eugène Delacroix, and Thomas Couture, and by 1886 the catalogue included excerpts from various sources for important works, such as Alphonse de Neuville’s Le Bourget, Jean-François Millet’s Water Carrier and Sower, John Everett Millais’s Bride of Lammermoor, Eugène Delacroix’s Muley-Abd-Err-Rahmann, Sultan of Morocco with his Officers and Guard of Honor, March, 1832, and August von Pettenkofen’s Hungarian Volunteers, as well as provenance information for the J. M. W. Turner watercolors.[33]

Edward Strahan’s Art Treasures of America and Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection

The collection received greater attention in Edward Strahan's two oversized deluxe catalogues, Art Treasures of America and Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection.[34] Strahan chronicled early Gilded Age collections, including Vanderbilt’s, in his encyclopedic three-volume Art Treasures of America, published between 1879 and 1882, devoting a heavily illustrated chapter to each major collection.[35] In the Vanderbilt collection chapter, five paintings, including Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Sword Dance and Louis XIV and the Grand Condé and Edouard Detaille’s Arrest of the Ambulance Corps, were depicted in full-page illustrations, and twenty-one illustrations of paintings, including Jean-François Millet’s Shepherdess and Plains of Barbizon, Théodore Rousseau’s Morning, Thomas Couture’s Realist, and Alphonse de Neuville’s Le Bourget were interspersed throughout the text. In his text, Strahan described the subjects and elucidated the narrative appeal of these works. For example, the archaeological quality and the appearance of historical accuracy in Alma-Tadema’s and Gérôme’s paintings, the simple dignity of Millet’s paintings, and the technical finesse of artists such as August von Pettenkofen, Emile Van Marcke, and Mariano Fortuny drew Strahan’s admiration. [36] Strahan also noted the popularity of Eduardo Zamacoïs’s King’s Favorite (fig. 10), a satirical painting whose sixteenth-century setting thinly veiled its commentary on the rule of Napoleon III, and de Neuville’s Le Bourget, a scene from the recent Franco-Prussian war.[37]

Shortly after Art Treasures of America appeared, the mammoth catalogue raisonné Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection was published.[38] Unprecedented in its elaborate scope, Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection set his art collection and extravagant home apart from others.[39] Never had a single collection been accorded such extensive coverage and lavish treatment. The inspiration for these grand tomes was probably European auction catalogues, particularly the heavily-illustrated auction catalogue printed for the Demidoff sale, from which Vanderbilt purchased a half-size bronze reduction of Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise and a monumental malachite vase.[40] However, Vanderbilt's surpassed this wealthy aristocrat’s publication in size and grandeur.

The oversized, richly illustrated four-volume edition of Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection was printed on Japan paper with plates tipped in. Each plate alone merited framing, and plates could be purchased separately for that purpose.[41] In the two volumes dedicated to the collection, full-page photogravures illustrated sixty-five paintings as well as three views of the main art gallery. In addition, two colored lithographs enlivened the gallery images, and engravers provided thirteen additional illustrations, including Charles Jacque’s own engraving after his painting, The Sheep Stable.

In the text, Strahan listed artists alphabetically in an encyclopedic fashion, with page-long entries or longer for twenty-two artists, whom he considered important; less prominent artists received shorter entries. His commentary (with some passages repeated verbatim from Art Treasures) focused on formal analyses and historical facts related to the subject matter depicted. Illustrations of works not listed in the formal art collection—decorative arts, including East Asian art and John La Farge’s stained glass windows—embellish the two volumes dedicated to the house. Lush, copious illustrations coupled with detailed, literary descriptions lent gravity to his collection, "one of the notable and recognized collections of the world," and acted as "a card of invitation to one of the artistic At Homes which have to so many people opened the gallery-doors heretofore."[42] This elaborate collection catalogue, though, did not replace the experience of seeing the works first-hand in Vanderbilt’s private gallery.

The Model Patron and His Private Gallery for the Public

Few art museums had as yet formed by the 1880s; consequently, private collections such as Vanderbilt’s were the primary repositories of art works in the United States. Although critics extolled the quality of Vanderbilt’s collection, on a par with the quality of the collection was the public’s perception that the collector’s motives were altruistic and not commercial, and that the collection had been formed for educational rather than for self-aggrandizing purposes.[43] Early Gilded Age critics and writers, such as James Jackson Jarves, hoped to put good artistic examples before the public to improve aesthetic taste, and Vanderbilt did just that with his artworks and collection catalogues.[44] Unlike collectors such as John Wolfe and George I. Seney, who each formed and sold several collections, Vanderbilt bought to keep, not to sell.[45] He did not purchase art for financial gain, for "selfish motives," or to fill his gallery with works by popular artists.[46] Significantly, unlike the majority of collectors, he regularly invited connoisseurs, art students, colleagues, and out-of-town visitors to view his collection in his new gallery built to house his artworks.[47]

His grand residence at 640 Fifth Avenue, completed in 1881, included a spacious private art gallery two stories high (figs. 11, 12) with a separate public entrance to the gallery on Fifty-First Street.[48] The main gallery, lit by skylights and gas light, held eighty-eight paintings and a smaller gallery held forty-four pictures, mainly watercolors. The pictures were hung symmetrically frame-to-frame Salon style and loosely grouped by subject matter. Vanderbilt’s gallery also served as a model—the only American one to be included in L’art dans la maison: Grammaire de l’ameublement by French art historian Henry Havard.[49]

Although not the first American collector to provide public access to his collection, Vanderbilt opened it more frequently and to more guests than did others.[50] Financier and art collector August Belmont had held only sporadic openings from the late 1850s to the 1870s.[51] Walters had begun inviting guests to view his collection in Baltimore as early as 1876, but only in springtime, and, unlike Vanderbilt, he charged a fifty-cent admission fee (with proceeds benefiting a charity).[52] Vanderbilt’s practice most closely resembled that of John Taylor Johnston, who had opened his gallery on Thursdays; Vanderbilt had attended several receptions there in the late 1860s.[53] Like Johnston, Vanderbilt’s gallery was open every Thursday between eleven and four in addition to special receptions; however, far greater numbers visited Vanderbilt’s gallery.[54]

For his opening reception held on March 1882, Vanderbilt invited 2,500 guests to view the collection in his new thirty-two by forty-eight foot gallery space.[55] Invitations were sent to men only, including prominent business men, artists, students, and visitors coming from outside New York City.[56] According to an awed reporter who attended the opening reception, Vanderbilt possessed the best collection of modern French pictures outside Paris.[57] Vanderbilt continued to open the gallery to the public weekly by admission cards and by request, and expanded the gallery space to 140 feet long within a year.[58] Some days upwards of three thousand people visited the gallery, according to one writer.[59] Another estimated that twenty thousand visitors had been to the gallery in the winter season of 1883, noting that Vanderbilt had been "more generous with his art treasures than any other American, living or dead."[60] By contrast, only 6,986 visitors, including some repeat guests including Vanderbilt, signed Johnston’s visitor register over a period of eleven years.[61] Vanderbilt’s gallery received more than double that number in a single season! Vanderbilt’s gallery became the standard of comparison against which other collectors assessed their own galleries. For example, Walters built a new art gallery that opened in 1884, though only 200 attended his opening; however, a sympathetic reviewer favorably compared Walters's gallery to Vanderbilt’s.[62]

Vanderbilt presided over his receptions, where he greeted guests, distributed small collection catalogues, and discussed the artworks, accompanied by sounds of an orchestra.[63] Connoisseurs and society seemed especially eager to attend his art receptions, and he was delighted to share his collection with his visitors.[64] After viewing the pictures, they left filled with admiration, having found his home and art collection splendid as well as appropriate for a man of his stature.[65] His guests received an education in the fine arts, which were then valued primarily for their moral and educational significance.[66]

Although he genuinely derived enjoyment out of sharing his collection, Vanderbilt ended the practice in March 1884, shortly before his death. Unfortunately, not all of his guests possessed a sincere interest in art education. Curious treasure seekers began snatching parts of tapestries and other goods, and wandered outside the gallery into the family’s private space.[67] A particularly unruly crowd in 1884 compromised the safety of his family and even necessitated police protection.[68] After two full years of public access, his collection would now be available only to family, friends, and acquaintances; he died shortly thereafter.

The Collection after Vanderbilt’s Death

Strahan, Avery, and others assumed that Vanderbilt would have had a provision in his will to create a public art gallery, but much to the dismay of civic-minded individuals, he left the collection to his family.[69] In his will, William directed that the collection was to remain intact in the Vanderbilt name, and that it was to hang in the gallery at 640 Fifth Avenue.[70] He stated his wish that "my present residence and my collection of works of art be retained and maintained by a male descendant bearing the name of Vanderbilt."[71] His heirs must have continued to allow some access to the gallery after his death since the last small catalogue was issued in 1886, the year that French critic, Durand-Gréville visited the gallery for his article.[72]

Although Vanderbilt left the collection to his heirs, he apparently had intended to build a museum.[73] He had attempted to purchase the plot of land opposite his mansion, and, according to contemporaries, he had set aside five million dollars to endow a new, grand museum there that would rival the British Museum.[74] His fund would have been larger than any museum endowment in the United States or Europe.[75] However, the Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum, which owned the land, refused to sell. He then sought another plot of land along Fifth Avenue for his museum, but this too, resulted in failure.[76] He died before he could secure a new plot of land for a museum to house the collection.[77]

His collection would not languish, however. At Samuel P. Avery’s behest, George W. Vanderbilt lent 135 works to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1902.[78] Vanderbilt intended to exhibit the collection at the museum for one year only, but extended the loan; it remained on view until December 1919.[79] Museum curator George Story declared that the value of the Vanderbilt collection, "from an artistic standpoint, can hardly be estimated."[80] During its first year on display, he received numerous applications from art students requesting permission to copy the works, and there were continued requests for reproductions of the artworks in the collection.[81] In 1907, George W. Vanderbilt permitted the curator to borrow Turner’s Fountain of Indolence for an exhibition of British paintings.[82] A special three-page section of the New York Times presented eleven illustrations of the most admired works, including a full-page reproduction of Millet’s Sower, Bouguereau’s Going to the Bath, Zamacoïs’s King’s Favorite, and Leys's Education of Charles V.[83] In 1919, the Vanderbilts began removing works from the museum, leaving only seventy-five of the original 135 pictures.[84] By early 1920, the museum’s executive committee decided to return the remainder of the collection to the family.[85] But for seventeen years, the William H. Vanderbilt Loan Collection of Modern Paintings hung in its own gallery in the museum.[86] When the family retrieved the pictures, contemporaries lamented their loss, particularly the Millet paintings, since the museum owned none.[87]

Henry Clay Frick at 640 Fifth Avenue

Nowhere was the Vanderbilt collection’s influence more evident than on industrialist Henry Clay Frick. Frick owned a copy of Vanderbilt’s collection catalogue, hung prints after works in Vanderbilt’s collection in his home, collected works by the same artists, and eventually lived in Vanderbilt’s 640 Fifth Avenue mansion with about seventy works from Vanderbilt’s collection. Frick purchased a four-volume Japan edition of Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection for $400, and paid an additional $100 for twenty separate etchings of plates in the book; he presumably hung them on the walls of his Pittsburgh residence, Clayton.[88] In addition, he purchased pastel reductions by Jean-François Millet of paintings in Vanderbilt’s collection, namely, The Sower (purchased in 1899) and The Knitting Lesson (purchased in 1896), which also hung at Clayton.[89]

Frick’s early collection, formed during the 1880s and 1890s, comprised works by many of the same artists Vanderbilt had collected.[90] In 1905 he signed a ten-year lease with Vanderbilt’s son, George W. Vanderbilt, for the Vanderbilt mansion at 640 Fifth Avenue, which came fully furnished, including much of the art collection.[91] Although George W. Vanderbilt had loaned 135 pictures to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the rest—including pictures by Bouguereau, Gérôme, Madrazo, Tissot, and Alma-Tadema—remained on display throughout the house at 640 Fifth Avenue.[92] According to the inventory, no Vanderbilt paintings remained in the mansion’s art gallery.[93]

Frick left the pictures hanging throughout the mansion as the 1905 inventory of the mansion’s contents indicated, and, in fact, he requested that several of the paintings on view at the Metropolitan Museum be transferred to 640 Fifth Avenue; however, George politely declined, and replied: "It is a pleasure to me to feel that my father’s collection is on view to the public at all times performing its educative function."[94] This statement reflects both the collection’s enduring appeal, as well as Vanderbilt’s strong interest in continuing his father’s educational mission. Unfortunately, no photographs of 640 Fifth Avenue exist from the time of Frick’s residence.[95]

Denied more paintings from the Vanderbilt collection, Frick quickly filled the Vanderbilt gallery space with his own pictures and published a small Vanderbilt-style collection catalogue in 1908.[96] This catalogue listed forty-eight pictures, most of which Frick acquired from Roland Knoedler of M. Knoedler & Co.; however, an inventory indicated that only thirty pictures hung in the main gallery.[97] Unlike Vanderbilt, Frick did not open the gallery to the public, though on several occasions he honored requests from individuals and small groups to view his collection.[98] Frick would build his own mansion with a large art gallery at One East Seventieth Street, completed in 1914; it opened to the public as The Frick Collection in 1935, fifty years after Vanderbilt’s death.[99]

What Happened to the William H. Vanderbilt Collection?

The difficult task of locating the paintings in the collection has revealed most of the prominent pictures to be in museums. Couture’s Enrollment of the Volunteers of 1792 is in the Museum of Art, Springfield, Massachusetts, and the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, acquired A Realist. Delacroix’s Muley-Abd-Err-Rahmann, Sultan of Morocco with His Officers and Guard of Honor, March, 1832 belongs to the Foundation E. G. Bührle, Zürich, Switzerland. The Musée d’Orsay acquired Gérôme’s Louis XIV and the Grand Condé; Meissonier’s Artist at Work is in the Cleveland Museum of Art; and, Information: General Desaix with the Army of the Rhine and Moselle can be found at the Dallas Museum of Art. Millet’s well-known Sower became part of the collection of the Yamanashi Prefectural Museum, Kofo, Japan. Millet’s Knitting Lesson and Shepherdess: Plains of Barbizon are now in the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts.[100]

Non-French works, including two of the Turners, also went to museums. Aptly, the Hastings Museum and Art Gallery acquired Turner’s Hastings, and Fountain of Indolence belongs to the Beaverbrook Foundation, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada. Turner’s other two pictures remain untraced. Robert Lehman bought Madrazo’s Masqueraders now hanging in the Lehman wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Alma-Tadema’s Sculpture Gallery is at the Memorial Art Gallery, Rochester, New York, and Millais’s Bride of Lammermoor can be found at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. The two most famous decorative objects from the house belong to public institutions: Grace Wilson Vanderbilt donated the reductions of Ghiberti’s bronze doors to the University of Nevada, Reno, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased the malachite Demidoff vase.

William Henry Vanderbilt’s influence on collectors and collecting should not be underestimated. His attention to his collection and its documentation and display reflected a growing awareness of the cultural treasures being amassed in the United States, and the importance of the collector’s role in disseminating that culture. In its entirety, the William H. Vanderbilt collection represented, as Low noted, the best example of a predominant trend in late nineteenth-century European painting and in art collecting in the United States, and Vanderbilt himself exemplified the beneficent collector. His attempts to build a museum anticipated the next generation of collectors who would form public museums for their art collections.[101] As a patron, Vanderbilt exemplified a judicious use of wealth that benefited the public. He opened his private collection to the public, presumably more than any other collector ever had. Additionally, his many catalogues lent authority, cultural significance, and sophistication to his collection and served as models for other collectors’ catalogues. His collection truly served as a model collection from the early Gilded Age, a time when the wealthiest man in America served as a cultural role model. Although 640 Fifth Avenue cannot be rebuilt or the collection reassembled, the William Henry Vanderbilt collection lives on, albeit in many different hands. The best way to view the collection today is still by slowly and delectably leafing through the grand leather-bound tomes of Mr. Vanderbilt's House and Collection.[102] His influence, however direct or indirect, lives on in museums such as The Frick Collection, The Morgan Library & Museum, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

Research for this article was conducted with support from the Fellowship Program at the Center for the History of Collecting in America at The Frick Collection and Art Reference Library, New York. The topic stems from a paper delivered at "The Art, Architecture, and Literature of the Gilded Age," The 13th Annual Salve Regina University Conference on Cultural and Historic Preservation, Newport, RI. I wish to thank editors Robert Alvin Adler, Petra Chu, and Isabel Taube as well as Porter Aichele, Spring 2010 Leon Levy Fellow at the Center for the History of Collecting in America, and Margaret Stenz for their insightful comments. In addition, I am grateful to Inge Reist, Samantha Deutch, and Esmée Quodbach at the Center for the History of Collecting in America; to the Frick Art Reference Library staff, especially Suzannah Massen, librarian extraordinaire; to Julie Ludwig and Susan Chore of the Frick Art Reference Library Archives; and to Catherine Lotspeich who coordinated numerous interlibrary loans on my behalf at Lipscomb Library, Randolph College.

[1] For an excellent survey of the state of art collecting prior to the Civil War period, see Lillian B. Miller, Patrons and Patriotism: The Encouragement of the Fine Arts in the United States, 1790–1860 (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1982). A shift in collecting European rather than American art began when August Belmont returned from Europe in 1857 with a collection of European academic works; however, due to Americans’ embarrassment at their poor showing of fine arts at the Universal Exposition of Paris in 1867, more collectors began buying European rather than American pictures. See Albert Boime, "America's Purchasing Power and the Evolution of European Art in the Late Nineteenth Century," in Saloni, gallerie, musei e loro influenza sullo sviluppo dell'arte dei secoli XIX e XX, ed. Francis Haskell (Bologna: CLUEB, 1979), 123–39, esp., on Vanderbilt, 124–25, 128–32; H. Barbara Weinberg, introduction to the reprint edition of Art Treasures of America, by Edward Strahan [Earl Shinn] (Philadelphia: George Barrie, 1879–82; repr. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1977), 1:1–13; Leanne Zalewski, "The Golden Age of French Academic Painting in America, 1867–1893" (PhD diss., City University of New York, 2009), 20–52. For the effect of the 1867 exposition on American painters, see also Carol Troyen, "Innocents Abroad: American Painters at the 1867 Exposition Universelle, Paris," American Art Journal 16, no. 4 (Autumn 1984): 2–29. For a general description of society in the early Gilded Age in New York, see Wayne Craven, Gilded Mansions: Grand Architecture and High Society (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008), 8–31. For an analogous study of collecting during this time in Pittsburgh, see Gabriel P. Weisberg, "From Paris to Pittsburgh: Visual Culture and American Taste, 1880–1910," in Collecting in the Gilded Age: Art Patronage in Pittsburgh, 1890–1910, ed. DeCourcey E. McIntosh, Gabriel P. Weisberg, and Alison McQueen, exh. cat. (Pittsburgh: Frick Art & Historical Center; Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 1997), 178–297.

[2] Edward Strahan [Earl Shinn], Mr. Vanderbilt's House and Collection, 4 vols. (Boston, George Barrie, 1883–84). A two-volume set of Mr. Vanderbilt's House and Collection, printed on Holland paper, and the four-volume set, printed on Japan paper, were published simultaneously. References are to the four-volume edition. The first two volumes of the four-volume set described the house built by architect John Butler Snook, and its interiors, designed by the Herter Brothers, as well as a vast array of decorative arts. The third and fourth volumes covered the fine art collection. In the two-volume Holland edition, the first volume features the house and the second volume covers the art collection. Strahan worked as an art critic for leading periodicals such as The Nation and Harper’s Weekly. See Ruth Krueger Meyer and Madeleine Fidell Beaufort, "The Rage for Collecting: Beyond Pittsburgh in the Gilded Age," in Weisberg, McIntosh, and McQueen, Collecting in the Gilded Age, 315–16. Other collection catalogues published are as follows: The Private Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 459 Fifth Avenue, New York (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1879), Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 640 Fifth Avenue, New York (New York: Putnam, 1882); Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 640 Fifth Avenue, New York (New York: n.p., 1884); and Catalogue of the W. H. Vanderbilt Collection of Paintings (New York: De Vinne Press, 1886); reprinted in Catalogue of the Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1902), 127–60.

[3] For influences on other collectors see, for example, William R. Johnston, William and Henry Walters, the Reticent Collectors (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 92. Dates for the collectors mentioned in this article are listed alphabetically as follows: August Belmont (1813–90), Henry Clay Frick (1849–1919), Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924), Henry Osborne Havemeyer (1847–1907), Louisine Havemeyer (1855–1929), John Taylor Johnston (1820–93), J. Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913), Alexander T. Stewart (1803–76), William T. Walters (1819–94), Henry T. Walters (1848–1931), and Catharine Lorillard Wolfe (1828–87).

[4] Only two pictures featured nudes: Mariano Fortuny’s Psyche and Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña’s Cupid’s Whisper.

[5] For collectors who owned works by Couture see Edward Strahan [Earl Shinn], Art Treasures of America (Philadelphia: George Barrie, 1879–1882), 1:80, 94, 134; 2:92, 102, 116; 3:22, 74, 94, 125, 126; for works by Delacroix, see 2:24; 3:74, 94, 125; for works by Millet, see 1:80, 94; 2:24, 98; 3:22, 40, 68, 74, 93, 94, 125; for works by Turner see 2:24, 50. (These works are only listed as "landscape," making verification difficult.) I thank Sylvia Tropp, who assisted me in combing through the collection lists in Art Treasures. John Taylor Johnston acquired the most important Turner, Slave Ship (now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) from art critic John Ruskin in 1872. Madeleine Fidell-Beaufort and Jeanne K. Welcher, "Some Views of Art Buying in New York in the 1870s and 1880s," Oxford Art Journal 5, no. 1 (1982): 51.

[6] A copy of William Henry Vanderbilt’s four-page will can be found in the Subject Files no. 242, New York House (Vanderbilt), 1913–1914," Henry Clay Frick Papers, The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York City, (hereafter, The Frick Papers).

[7] "Vanderbilt Home in 5th Ave. Is Sold," New York Times, May 17, 1940, 18. See also The William H. Vanderbilt Collection of Distinguished Barbizon and Genre Paintings . . . sold by order of Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt (New York: Parke-Bernet Galleries, Inc., 1945). What remained at this time were 175 pictures, including Jean-François Millet’s Sower, though excluded were the four J. M. W. Turner pictures and Thomas Couture’s Enrollment of the Volunteers of 1792, Gustave Doré’s Twilight in Scotland, Alphonse de Neuville’s Le Bourget, Ernest Meissonier’s portrait of Vanderbilt, and the beloved Information: General Desaix with the Army of the Rhine and Moselle. Eugène Delacroix’s Muley-Abd-Err-Rahmann, Sultan of Morocco with His Officers and Guard of Honor, March, 1832 remained in the family until Cornelius Vanderbilt’s widow, Grace, died in 1953. Grace donated Edouard Detaille’s panorama, The Evening of Rezonville, August 16, 1870 to the Park Avenue Armory in New York. The Vanderbilt family retained Vincenzo Gemito’s sculpture of Meissonier, José Villegas Cordero’s Christening, and the ceiling paintings from 640 Fifth Avenue by Pierre-Victor Galland and Evariste-Vital Luminais, which are all now in the Biltmore mansion in Asheville, North Carolina. I thank Lori Garst, Curatorial Assistant at the Biltmore estate, for a list of objects from 640 Fifth Avenue that are now at Biltmore. In addition to those mentioned above are several family portraits as well as paintings that hung in the stables. The ceiling paintings by Luminais and Galland are in storage and in poor condition. Lefebvre’s ceiling painting, Dawn, is untraced and may have been destroyed with the mansion.

[8] Strahan, Mr. Vanderbilt's House and Collection; The Private Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 459 Fifth Avenue, New York (1879), Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 640 Fifth Avenue, New York (1882); Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 640 Fifth Avenue, New York (1884); and Catalogue of the W.H. Vanderbilt Collection of Paintings (1886); Samuel P. Avery, The Diaries 1871–1882 of Samuel P. Avery, ed. Madeleine Fidell-Beaufort, Herbert L. Kleinfield and Jeanne K. Welcher (New York: Arno Press, 1979); and George A. Lucas, Diary of George A. Lucas: An American Art Agent in Paris, 1857–1909, ed. Lilian M. C. Randall, 2 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979). The William H. Vanderbilt Collection of Distinguished Barbizon and Genre Paintings . . . sold by order of Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt. Letters are as follows: William H. Vanderbilt letters to Samuel P. Avery, 1878–1880, undated, Samuel P. Avery papers, Thomas J. Watson Library, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City; letters from various artists to Lucas as follows are in the George A. Lucas Papers: "Jean Baptiste Edouard Detaille," Box 4; "Jules-Joseph Lefebvre," Box 7; Evariste Vital Luminais," Box 8; "Jean Louis Ernest Meissonier," Box 9, Archives and Manuscript Collections, Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland. I thank Emily Rafferty, Associate Librarian & Archivist at The Baltimore Museum of Art for giving me access to the Lucas letters. A listing of Vanderbilt’s collection, presumably from an 1885 catalogue (that I have been unable to locate), as well as a reprint of an article presumably from 1883 (no source provided), was published online by Theresa Franks for Fine Art Registry. See http://www.fineartregistry.com/articles/2011-02/tour-and-art-review-of-william-h-vanderbilt-picture-gallery.php (accessed September 22, 2011). Only eleven works from the Vanderbilt collection are illustrated in this article, as well as numerous presumably comparable examples of artworks by artists represented in the collection. The use of so few illustrations and the inclusion of works not in his collection do a disservice to his original collection. I thank Petra Chu for bringing this site to my attention.

[9] See William H. Vanderbilt Collection," 81–87; Mr. Vanderbilt's Gallery," New York Times, December 10, 1885, 2; "Art Attractions of New York," National Academy Notes, no. 7 (1887), 129; "C. Vanderbilt Gets Mansion and Art," New York Times, March 10, 1914, 5; "Vanderbilt’s New House," New York Times, March 8, 1882, 2; and E. Durand-Gréville, "French Pictures in America," Studio n.s. 3, no. 2 (August 1887), 30, reprinted nearly verbatim in E. Durand-Gréville, "Private Picture-Galleries of the United States," Connoisseur 2, no. 3 (March 1888), 138. The Durand-Gréville articles were translations from the French. See E. Durand-Gréville, "La peinture aux Etats-Unis," Gazette des beaux-arts 36 (September 1887): 250–55.

[10] I rely sparingly on William A. Croffut’s 1886 biography and avoid unsubstantiated anecdotal accounts. See W. A. [William Augustus] Croffut, The Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune (Chicago, New York, and San Francisco: Belford, Clarke & Co., 1886), 163–74, 246–47. See also W. A. Croffut, "William H. Vanderbilt," Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly 21, no. 2, February 1886, 130–39.

[11] No information regarding his art collection could be found in the Special Collections & University Archives at Vanderbilt University, the Manuscript Department of the New-York Historical Society, or the Vanderbilt Museum, Centerport, New York. The archives listed for William H. Vanderbilt in the Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America, Frick Art Reference Library, turned up precious little. Several letters regarding specific art works are among the George A. Lucas papers at the Baltimore Museum of Art as well as in the Samuel P. Avery papers at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and are set out in note 8. Various notes and an essay can be found in the August Jaccaci papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. None of these, however, is extensive. I have attempted, to no avail, to contact descendants of George W. Vanderbilt.

[12] S. G. W. Benjamin, "The Paintings of Mr. William H. Vanderbilt," Independent 34, no. 1738 (March 23, 1882): 7.

[13] See William H. Vanderbilt Collection," Collector 1, no. 11 (April 1, 1890): 81.

[14] Various biographies were written about his father, "Commodore" Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794–1877), founder of the family fortune, and about the Vanderbilt family, that include only brief sections about William, with little mention of the art collection. See, for example, T. J. Stiles, The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt (New York: Vintage Books, 2010) 549–51; Louis Auchincloss, Vanderbilt Era: Profiles of a Gilded Age (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1989), 27–33; Arthur T. Vanderbilt, Fortune’s Children (New York: William Morrow & Co., 1989), 55–83; and Edwin Palmer Hoyt, The Vanderbilts and Their Fortunes (Garden City: Doubleday, 1962), 228–53.

[15] August Jaccaci and John La Farge, eds., Noteworthy Paintings in Private American Collections, 2 vols. (New York: A. F. Jaccaci Co., 1907). See also Flaminia Gennari-Santori, The Melancholy of Masterpieces: Old Master Paintings in America, 1900–1914 (Milan: 5 Continents, 2003), 151–225, esp. 191–92. Notes and essays for the entire project can be found in August F. Jaccaci Papers, 1889–1935, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. See Letters from John La Farge to August Jaccaci, December 21, 1903; December 22, 1903; January 19, 1904; January 20, 1904; letters from August Jaccaci to Grace Barnes (La Farge’s secretary), February 19, 1904; March 2, 1904; and letter from August Jaccaci to John La Farge, July 9, 1903. American artist and critic, Will Hicock Low drafted an essay. See W. H. Low, "The Vanderbilt Collection of Modern Paintings," 1–68, in August F. Jaccaci Papers 1889–1935.

[16] Low, "The Vanderbilt Collection of Modern Paintings," 1, 9.

[17] Craven, Gilded Mansions, 88–105; Lila Boren Stillson, "The William Henry Vanderbilt Mansion: The Pluralistic Aesthetic in America" (MA thesis, University of Texas at Austin, 1984); and Mary Dutton Boehm, "Herter Brothers and the William H. Vanderbilt House" (MA thesis, Parsons School of Design, 1991). For contemporary commentary, see George W. Sheldon, Artistic Houses (New York: Appleton & Co., 1883–1884; repr. New York: Benjamin Blom, 1971), 114–21.

[18] See Craven, Gilded Mansions, 81–105. The art gallery is described on pages 101–4; see 103–4 for the Towner anecdotes. See also René Brimo, L'évolution du goût aux Etats-Unis d'après l'histoire des collections (Paris: James Fortune, 1938), 50–51. William Ayres only briefly acknowledged the collection’s status in his study. See William S. Ayres, "The Domestic Museum in Manhattan: Major Private Art Installations in New York City, 1870–1920" (PhD diss., University of Delaware, 1993), 31, 52–58. See also Henry J. Duffy, "New York City Collections 1865–1895" (PhD diss., Rutgers University, 2001), 10–13.

[19]The William H. Vanderbilt Collection of Distinguished Barbizon and Genre Paintings . . . sold by Order of Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt. Catharine Lorillard Wolfe was the only collector of Vanderbilt’s generation to bequeath her entire collection of what was then modern European art to an art museum. Her gift of 143 pictures entered the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1887, two years after Vanderbilt’s death. Vanderbilt left $100,000 to the museum at his death, but no pictures. See Metropolitan Museum of Art, Annual Reports of the Trustees of the Association, from 1871 to 1902 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1902), 327, 383. For more information about Wolfe, see Dianne Sachko Macleod, Enchanted Lives, Enchanted Objects: American Women Collectors and the Making of Culture, 1800–1940 (University of California Press, 2008), 61–71; Rebecca A. Rabinow, "Catharine Lorillard Wolfe: The First Woman Benefactor of the Metropolitan Museum of Art," Apollo, no. 433 (March 1998): 48–55; Margaret Laster, "The Collecting and Patronage of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe in Gilded-Age New York and Newport," in Power Underestimated: American Women Art Collectors, ed. Inge Jackson Reist and Rosella Mamoli Zorzi (Venice: Marsilio, 2011), 79–99; and Zalewski, "Golden Age of French Academic Painting," 174–81. William T. Walters, Vanderbilt’s other prominent contemporary, left his collection to his son, Henry, who later formed an eponymous museum in Baltimore; the Walters Art Gallery, now called the Walters Art Museum, opened to the public in 1909. By that time, the collection of father and son combined totaled over 22,000 works from a broad array of time periods and cultures. For an extensive biography of the collectors, see William R. Johnston, William and Henry Walters, the Reticent Collectors (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999).

[20] Gennari-Santori, Melancholy of Masterpieces, 71–73. For more about the old master painting collecting boom, see Nancy T. Minty, "Dutch and Flemish Seventeenth-Century Art in America, 1800–1940: Collections, Connoisseurship and Perceptions" (PhD diss., New York University, 2003). For a recent, lively, and well-researched account, see Cynthia Saltzman, Old Masters, New World: America's Raid on Europe's Great Pictures (New York: Penguin, 2008).

[21] Avery, The Diaries 1871–1882 of Samuel P. Avery; and Lucas, Diary of George A. Lucas. Numerous entries in each dealer’s diaries mention Vanderbilt.

[22] See "William H. Vanderbilt Collection," 81; "William H. Vanderbilt," Magazine of Western History 8, no. 3 (July 1888): 245, (hereafter cited as "William H. Vanderbilt," Western History).

[23]Private Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 459 Fifth Avenue, New York; and Croffut, Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune, 147.

[24] Samuel P. Avery, "Note" in Catalogue of the Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1902), 127.

[25] William Henry Vanderbilt’s will, Subject Files no. 242, New York House (Vanderbilt), 1913–1914, The Frick Papers. He gave his wife his picture collection, but stated that she could not sell any works of art. See also Croffut, Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune, 163.

[26] A catalogue for August O. Belmont’s collection was published for a benefit exhibition, but not for his own purposes. This catalogue listed only artists’ names, the cities where they worked, and titles of art works. See The Belmont Gallery, on exhibition for the benefit of the U. S. Sanitary commission, Monday, April 4th, to Saturday, April 9th (New York: John A. Gray & Green, 1864). See also The Collection of Paintings, Drawings and Statuary, the Property of John Taylor Johnston, Esq. (New York: Somerville Art Gallery, 1876); and Catalogue of the A. T. Stewart Collection of Paintings, Sculptures, and Other Objects of Art (New York: American Art Association, 1887).

[27] See Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 640 Fifth Avenue, New York (1884); and Collection of W. T. Walters, 65 Mt. Vernon Place, Baltimore (Baltimore: n. p., 1884).

[28] Johnston, William and Henry Walters, 92; Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 640 Fifth Avenue, New York (1882); and Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 640 Fifth Avenue, New York (1884).

[29]Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 640 Fifth Avenue, New York (1882);and Collection of W. T. Walters, 65 Mt. Vernon Place, Baltimore.

[30]Collection of Paintings, Drawings and Statuary, the Property of John Taylor Johnston, Esq.

[31]Private Collection of W. H. Vanderbilt, 459 Fifth Avenue, New York, 23–24, 32–35, 39–42.

[32] Ibid.

[33]Catalogue of the W. H. Vanderbilt Collection of Paintings (1886), 32–34, 41, 43–44, 49, 52, 64–65.

[34] Strahan, Art Treasures of America; and Strahan, Mr. Vanderbilt's House and Collection.

[35] Strahan, Art Treasures of America, 3:95–108.

[36] Ibid., 97.

[37] Ibid., 101, 103.

[38] Strahan, Mr. Vanderbilt's House and Collection.

[39] See Arnold Lewis, James Turner, and Steven McQuillin, Opulent Interiors of the Gilded Age (New York: Dover, 1987), 119.

[40]Palais de San Donato: Catalogue des objets d'art et d'ameublement, tableaux (Florence: n.p., 1880).

[41] Five hundred copies of the four-volume edition were printed on Japan paper. One thousand copies of the two-volume edition were printed on Holland paper. The illustrations and text are identical in each; however, in the Japan edition, the prints are tipped in, rather than printed on the page as in the Holland edition. Henry Clay Frick, for example, purchased prints to hang in his home. See Colin B. Bailey, Building the Frick Collection: An Introduction to the House and Its Collections (New York: Frick Collection in association with Scala, 2006), 19. Frick paid $100 for a set of twenty satin etchings. A receipt for these prints, purchased from Glynn & Barrett in 1885, can be found in Invoice Book no. 2, receipts dated July 29, 1885, Henry Clay Frick Papers, The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, New York City. I thank Emilia S. Boehm, Assistant Curator of Collections and Exhibitions at the Frick Art & Historical Center, Pittsburgh, for a list of twelve satin prints that Frick purchased.

[42] Strahan, Mr. Vanderbilt's House, 1:viii.

[43] "William H. Vanderbilt," Western History," 245; Croffut, Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune, 163; "Art Notes," Art Journal (New York) 8, no. 16 (1882): 125–26. Strahan, presumably acting as a mouthpiece for Vanderbilt, reflected Vanderbilt’s intentions. He stated that the catalog and collection came "from a free-hearted open generosity that feels there is nothing to conceal and believes there is something to instruct." See Strahan, Mr. Vanderbilt's House, 1:vi.

[44] James Jackson Jarves, "Fostering the Fine Arts," New York Times, July 5, 1880, 5.

[45] Preface to Modern Paintings (New York: Fifth Avenue Art Galleries, 1894); Champion Bissell, "Modern Pictures and the New York Market," Belford's Monthly and Democratic Review 8, no. 45 (February 1892): 686.

[46] "William H. Vanderbilt," Western History, 245.

[47] "Mr. Vanderbilt’s Art Levee," New York Times, December 21, 1883, 2.

[48] For descriptions of the gallery spaces see, for example, Craven, Gilded Mansions, 101–4; Stillson, "William Henry Vanderbilt Mansion," 61–67; and "The Vanderbilt Houses," Decorator and Furnisher 12, no. 2 (May 1888): 53–56.

[49] Henry Havard, L’Art dans la maison: Grammaire de l’ameublement (Paris: Edouard Rouveyre, 1887), 2:227. I thank Petra Chu for bringing this publication to my attention. See also Stillson, "William Henry Vanderbilt Mansion," 66–67.

[50] For a history of residential art galleries prior to Vanderbilt’s, see Anne McNair Bolin, "Art and Domestic Culture: The Residential Art Gallery in New York City, 1850–1870" (PhD diss., Emory University, 2000). For a brief summary of European art galleries, see Albert Boime, "Entrepreneurial Patronage in Nineteenth-Century France," in Enterprise and Entrepreneurs in 19th and 20th Century France, ed. Edward C. Carter, Robert Forster, and Joseph N. Moody (Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1976), 137–207. For example, at mid-century, Parisian financier Pourtalès-Gorgier opened his private gallery, albeit sparingly, to visitors, artists, and critics. See Boime, "Entrepreneurial Patronage," 148–49. Vanderbilt may have emulated the picture hanging styles he saw on his travels to Paris and London.

[51] Bolin, "Art and Domestic Culture," 72.

[52] William T. Walters initially allowed artists and critics into his picture gallery and in 1878 began opening it for several months a year for a fifty cent admission. All proceeds went to the Poor Association. See Johnston, Reticent Collectors, 77, 79.

[53] Johnston’s register covered the years 1865 to 1876, the year he sold his collection. John Taylor Johnston Visitor Books, John Taylor Johnston Collection, 1832–1981, Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, New York. Vanderbilt attended receptions held April 12, 1866, April 25, 1867, and April 6, 1871. See also Bolin, "Art and Domestic Culture," 96.

[54] "Notes," Critic 12 (January 2, 1886): 12; Samuel P. Avery, "W. H. Vanderbilt's Pictures on View," New York Times, May 4, 1902, 15; and Lewis, Turner, and McQuillin, Opulent Interiors of the Gilded Age, 119.

[55] "Vanderbilt’s New House," 2.

[56] "Mr. Vanderbilt’s Art Levee," 2.

[57] "Vanderbilt’s New House," 2.

[58] Avery, "W. H. Vanderbilt's Pictures on View," 15; Croffut, Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune, 174; "Mr. Vanderbilt’s Art Levee," 2.

[59] See "William H. Vanderbilt," Western History, 245–46.

[60] "Personal," Harper’s Weekly, July 5, 1884, 427.

[61] John Taylor Johnston Visitor Books, John Taylor Johnston Collection, 1832–1981, Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, New York.

[62] Review quoted from the New York Sun, February 27, 1884, reprinted in The Art Collections of Mr Wm. T. Walters, Catalogue and Descriptive and Critical Articles (Baltimore: n. p., [1884]).

[63]"Mr. Vanderbilt’s Art Levee," 2.

[64] See "William H. Vanderbilt," Western History, 244; and R. R. [Roger Riordan], "The Fifth Avenue," Art Amateur 17, no. 4 (September 1887): 74.

[65] "The Listener," Studio 2, no. 52 (December 29, 1883), 301; W. R. Houghten, ed., Kings of Fortune (Chicago: Loomis National Library Association,1888), 256.

[66] Miller, Patrons and Patriotism, 221.

[67] See Croffut, Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune, 174; and "William H. Vanderbilt," Western History, 246.

[68] "A Talk with Vanderbilt," New York Times, February 16, 1884, 2.

[69] See Avery, "W. H. Vanderbilt's Pictures on View," 15; Croffut, Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune, 163; "William H. Vanderbilt," Western History, 244; Montezuma, "My Note Book," Art Amateur 14, no. 3 (February 1886), 54; J. E. Brush, "Death of the Rich Man," Herald of Gospel Liberty 77, no. 51 (December 17, 1885): 780. See also "C. Vanderbilt Gets Mansion and Art," New York Times, March 10, 1914, 5; and "C. Vanderbilt in Vanderbilt Palace," New York Times, April 25, 1914, 15.

[70] He gave his wife his picture collection, but stated that she could not sell any works of art. He named his son George W. Vanderbilt as the next in line to inherit the picture collection. William Henry Vanderbilt’s will, p. 2, Subject Files no. 242, The Frick Papers.

[71] Ibid., 4.

[72] See Durand-Gréville, "Private Picture-Galleries of the United States," 138. Although this catalogue appeared after Vanderbilt’s death, plans for its printing were likely in place prior to his passing in December 1885. Vanderbilt’s name remained a powerful connection to the art world since savvy sellers of inexpensive paintings falsely invoked his name, along with Stewart’s, as eager buyers of these works. See "The Picture of Commerce," Harper’s Weekly 33, May 18, 1889, 403.

[73] See Croffut, Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune, 246; and "Notes," Critic, 12.

[74] Croffut, Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune, 246.

[75] A less reliable source, Vanderbilt’s ambitious daughter-in-law, Alva, wrote that Vanderbilt had agreed to her plan to build a conservatory of music on the plot. See Alva Belmont, "Memoirs of Alva Vanderbilt Belmont," 112, Matilda Young Papers, c. 1928, Archives of the William R. Perkins Library, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

[76] "Notes," Critic, 12.

[77] "No Foundation for the Story," New York Times, January 28, 1886, 8.

[78] Avery, "W. H. Vanderbilt's Pictures on View," 15; Avery served on the board of trustees at the Metropolitan Museum of Art until 1904.

[79] Ibid.

[80] George H. Story, preface to Catalogue of the Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1902), 6.

[81] Unfortunately, George W. Vanderbilt failed to respond to the requests for permission to copy works. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thirty-third Annual Report of the Trustees of the Association [1902] (New York, 1903), 17; see Letter from the Assistant Secretary [to Adolph Braun, of Messrs. Braun, Clement & Co.] to George W. Vanderbilt, May 8, 1906, 'Vanderbilt, William H. –Loan Collection Lent by Geo. H. [sic] Vanderbilt 1902–03, 1905–09, 1911–12 V2886," Office of the Secretary of Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, New York, (hereafter, Vanderbilt, William H. –Loan Collection).

[82] Letter from Edward Robinson to George W. Vanderbilt, January 25, 1907, Vanderbilt, William H. –Loan Collection.

[83] "Striking Paintings of the Vanderbilt Collection," New York Times, May 14, 1914.

[84] "Vanderbilt Art Withdrawn," New York Sun, December 10, 1919; "Italian Ambassador Chief Guest at Dinner," New York Herald, December 8, 1919. Articles located in Vanderbilt, William H. –Loan Collection.

[85] Letter from Edward Robinson to Cornelius Vanderbilt, January 20, 1920, Vanderbilt, William H. –Loan Collection.

[86]Catalogue of the Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1902), 7. See gallery map. The William H. Vanderbilt Collection of Modern Paintings occupied gallery 8, and the Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection of modern pictures occupied galleries 9 and 10. Unfortunately, no photographs of the Metropolitan Museum’s installation of Vanderbilt’s collection exist in the museum’s archives.

[87] "Notes," Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 15, no. 2 (February 1920): 43; "Fear Museum May Lose Art of Mr. Cornelius Vanderbilt," New York Herald, September 24, 1914, 7.

[88] Invoice Book no. 2, receipts dated June 6, 1884, November 6, 1884, March 21, 1885, July 29, 1885, and March 17, 1886, Frick Papers. Twelve of the twenty satin prints remain in the collection of The Frick Art & Historical Center. Among them are Ernest Meissonier’s Arrival at the Château and Information: General Desaix and the Peasant, Eduardo Zamacoïs’s The King’s Favorite, Mihály Munkácsy’s Two Families, Charles Jacque’s Sheep Stable, and Théodore Rousseau’s Farm on the Oise. I thank Emilia S. Boehm, Assistant Curator of Collections and Exhibitions at the Frick Art & Historical Center, Pittsburgh, for this list.

[89] A receipt for these prints, purchased from Glynn & Barrett in 1885, can be found in Invoice Book no. 2, receipts dated July 29, 1885, The Frick Papers. See also "Art Files-Inventories & Lists; Pictures at Clayton, 1902–1921," The Frick Papers; and DeCourcey E. McIntosh, "Demand and Supply: The Pittsburgh Art Trade and M. Knoedler & Co," in Weisberg, McIntosh, and McQueen, Collecting in the Gilded Age, 146.

[90] These artists included William Bouguereau, Rosa Bonheur, Jules Dupré, Jules Breton, Edouard Detaille, Josef Israëls, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Jean-François Millet, Johann Georg Meyer, Emile van Marcke, Félix Ziem, John Linnell, J. M. W. Turner, Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña, Théodore Rousseau, Charles Daubigny, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Constant Troyon, and Charles Jacque.

[91] "Inventory of Furniture, Rugs, Carpets…Oil Paintings…Belonging to Mr. George W. Vanderbilt at No. 640 Fifth Avenue, New York City, and leased to Mr. H. C. Frick, dated November 6, 1905," Henry Clay Frick Papers, New York House (Vanderbilt) 1905, box 11, folder 23, The Frick Papers.

[92] Ibid. Among the better known pictures left in the mansion were Hendrik Leys's The Rights of the City Accorded to Pallavicino at Antwerp 1541, Jules Breton’s Brittany Woman, Rosa Bonheur’s Noonday Repose, Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s Entrance to the Roman Theater, and Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Bashi-Bouzouk, all hanging in the drawing room. Additionally, Gustave Doré’s Twilight in Scotland hung in the library, and Jules-Joseph Lefebvre’s Attiring the Bride graced the marble entrance hall. Raimundo Madrazo’s Masqueraders and Paul-Jean Clays's City of Antwerp from the River, among others, adorned the walls of Mrs. Adelaide Childs Frick’s room, and Eduardo Zamacoïs's King’s Favorite hung in a second floor bedroom.

[93] "Inventory of Furniture, Rugs, Carpets…Oil Paintings…Belonging to Mr. George W. Vanderbilt at No. 640 Fifth Avenue, New York City, and leased to Mr. H. C. Frick, dated November 6, 1905."

[94] Letter from George W. Vanderbilt to Henry Clay Frick, Biltmore, n.d. [1905], Subject Files no. 242, The Frick Papers. Unfortunately, the pictures in question were not listed in this letter.

[95] I thank Julie Ludwig, archivist, The Frick Collection/Frick Art Reference Library Archives, for her attempts to locate photographs.

[96]Catalogue of the Henry C. Frick Collection of Paintings (New York: n.p., 1908).

[97] "Memorandum of Paintings in the House at 640 Fifth Ave., New York City, as counted by F. W. McE., June 4, 1914, dated June 5, 1914, Henry Clay Frick Art Collection Files, 1881–1920, series V: Miscellaneous, 1901–1919, box 6, folder 11, The Frick Papers.

[98] Letter from unnamed sender to H. C. Frick, March 23, 1911; Letter from S. L. Adler to H. C. Frick, March 19, 1913 and March 22, 1913; and Letter from George Edward Colon to Henry C. Frick, December 29, 1913, in "Art Files-Correspondence: Requests to Visit the Gallery at 1 E. 70, 1917–1920, n.d.," box 12, folder 11, The Frick Papers.

[99] Colin B. Bailey, Building the Frick Collection: An Introduction to the House and Its Collections (New York: Frick Collection in association with Scala, 2006).

[100] The Millet paintings as well as the following paintings were acquired from the 1945 sale: Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s Road by the Water, Eugène Fromentin’s Arabs Watering Horses, and Alfred Stevens's Morning Call, now called The Visit, all now in the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts.

[101] Old-master collectors including Isabella Stewart Gardner, J. Pierpont Morgan—who had been Vanderbilt’s neighbor before Vanderbilt moved from 459 Fifth Avenue to the mansion at 640 Fifth—and Henry Clay Frick, among others, had not formed private museums until the early twentieth century. Gardner opened her museum during her lifetime; Morgan left his collection to his son who later formed the museum, and Frick’s collection became public after his widow’s death. The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum opened in 1903. Jack Morgan established a gallery in 1924, now the Morgan Library and Museum. Frick died in 1919, his wife died in 1931, and the Frick Collection opened to the public in 1935. For a discussion of these collections, as well as other private collections that became public art museums, see Anne Higonnet, A Museum of One's Own: Private Collecting, Public Gift (New York: Prestel, 2009). Louisine and Henry Osborne Havemeyer, known for their French Impressionist paintings, donated their collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1929. See Frances Weitzenhoffer, The Havemeyers: Impressionism Comes to America (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1986).

[102] Henry Clay Frick’s pristine and weighty four-volume Japan edition of Mr. Vanderbilt’s House and Collection can be consulted at the Frick Art Reference Library, The Frick Collection, New York, NY.