The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

“Gentlemen, whether you like it or not, the feeling for religion has in the last six years regained a power which no one could have foreseen.”[1]

A member of France’s Chamber of Deputies made this surprising declaration in 1837, noting the dramatic religious revival that had taken place in France in recent years. One particular religious event, a Mariophanic occurrence, may have contributed to this phenomenon. It also led to a new iconography for the Virgin Mary (fig. 1). This is the subject of my article, in which I attempt to show how a new, potent image of the Virgin became popular because it emerged at a propitious moment, politically, and because new technologies helped to widely propagate it.

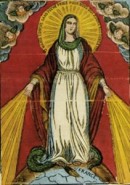

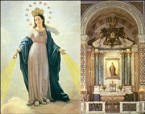

In the chapel of an order of nuns, The Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, located on the rue du Bac, the Virgin Mary appeared three times to a twenty-four-year-old nun, Catherine Labouré (1806–76). The first apparition occurred on July 18, 1830, the second and third on November 27, and December 30, the same year. During the course of these appearances, the Virgin Mary instructed Labouré to have a medal designed with her image as the Immaculata. Soon after the medal was designed and produced in large numbers, the image on it became known as The Virgin Mary of the Immaculate Conception of the Miraculous Medal or alternatively The Virgin Mary of the Miraculous Medal. The distinguishing feature of the design is the rays of light emanating from the hands of the Virgin, who stands erect with her arms extended, knees lightly flexed and her ankles pressed together (fig. 2). She gazes downward as if listening to the pleas of the devout, and not upward toward God the Father or the Son as she was traditionally depicted in paintings with the title The Immaculate Conception (fig. 3). Labouré reported the mystical events and the Virgin’s precise instructions for the design to a priest, Père Jean–Marie Aladel (1800–65), who in turn reported the story of these events to his superior.[2]

After learning of the apparitions and the Virgin’s mandate, the archbishop of Paris, Hippolyte de Quélen (1778–1839), held an inquiry and agreed to have a medal struck.[3] Due to a cholera epidemic in Paris, it was not until May 1832 that the well-known goldsmith, Adrien-Jean-Maximilien Vachette (1753–1839) at the rue des Orfèvres no. 54, received the order for 20,000 medals, which were, at first, little, flat, oval pieces of an unidentifiable alloy (fig. 4).[4] One million were distributed by the end of 1835 and by December 1836, Vachette's firm (founded in 1815) had sold two million in silver or gold, and eighteen million of a cheaper metal.[5] Eleven other Parisian goldsmiths produced twenty million medals, and four more in Lyon worked to meet the demand. Twenty million medals were made in 1837 alone.[6]

The publicity about the apparitions began with a short notice of sixty-four pages published by Père Aladel in 1834. It recorded the apparitions and outlined the graces promised by the Virgin and obtained by owning the medal. Aladel’s book sold rapidly; eight more editions had appeared by 1842.[7] Throughout her life, Labouré did not want to be identified as the seer of the apparitions. It was only in 1854, after the papal declaration of The Immaculate Conception as dogma of the Church, that her name became known.[8]

Mediation and Design

The third of Labouré's three apparitions had two phases, which are known as "The Virgin of the Globe" and "Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal." Labouré described the first phase of the vision as one in which the Virgin Mary held the globe as a symbol of the entire world in her hands, while beseeching God for mercy on everyone (fig. 5). That image was followed by a vision of the Virgin Mary standing with her arms swept wide in a gesture of compassion, while from her fingers rays of brilliant light streamed downward. Labouré reported: “I would not know how to express the beauty and brilliancy of these rays.”[9] Labouré related that the Virgin Mary appeared “as a picture” encircled within an oval frame inscribed with the words: O Mary, Conceived without Sin, Pray for Us Who Have Recourse to You.[10] The image then turned around and revealed a cross, surmounted by the letter “M,” and two hearts (fig. 6). It was then that Labouré heard a voice, presumably that of the Virgin Mary, commanding her to have a medal struck according to this vision.[11]

Père Aladel, who worked with Vachette on the design of the medal, reported that they were puzzled as how to represent the attitude of the Blessed Virgin, “for in the apparition, she was enveloped in waves of light in one instant, yet in another moment rays of light emanated from her hands."[12] In his study of unpublished archival material as well as the records of the 1836 Canonical Inquiry of Labouré and her reports of the paranormal events, Thomas Dirvin wrote that Père Chevalier, Catherine's last director, in his official deposition, “expresses the opinion that the change from a figure of the Virgin Mary holding a globe was made because of the difficulty of representing the attitude of the first phase in metal.”[13] René Laurentin’s 1980 study of the deposition records of the Beatification Tribunal concluded that Labouré's description of her vision was different from the design on the medal.[14] Faced with the difficulty of illustrating the young nun’s vision, Aladel and Vachette looked to earlier models in engravings, suggesting that technical limitations superseded fidelity to the reported image of the Virgin with The Globe. The change did not alter the belief of eager recipients about the radical nature of this image because it was a mandate uttered by the holy personage. Nor did it alter their belief in her power to dispense divine graces through splays of light. The compelling conviction of these beliefs among the populace was the basis for the worldwide dissemination of the medal.

There is no doubt that mediation between a narrator, particularly one describing a supernatural vision, and an artist’s rendition of this narration is an imperfect process that is shaped by aesthetic values, technical capabilities, religious criteria and social demands. Perhaps, the best example of the difficulties inherent in this process is the presentation of the vision of Bernadette Soubirous (1844–79). In 1858, at the age of fourteen, she was the seer of the Marian apparitions at Lourdes, France. (The vision announced herself with the same title as did the Virgin Mary to Labouré: “I am the Immaculate Conception.”) Soubirous’s vision was mediated by a male artist, the Lyonese sculptor, Joseph Hugues Fabisch (1812–86), who dramatically overhauled her description. A member of the French Academy at Lyon and a professor of sculpture at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, he was commissioned by wealthy patrons to create “a statue which would depict as accurately as possible the dress and posture of the apparition.”[15] Lyon, the center of nineteenth-century religious art production, was known for an art that was tradition-bound, classical in form, and conservative in its iconography. Documents of the meetings between the artist and the visionary, as well as meetings between the local priest of Lourdes, Abbé Dominique Peyramale (1811–77) and Soubirous, recount her repeated and consistent criticisms of the sculptor’s version.[16] She complained that the sculpture was not what the Virgin had looked like in her vision (fig. 7, in situ). Fabisch had made the figure look too old, too serious, too cold and unwelcoming. “Oh, Monsieur, how cold it is!”[17] Among the discrepancies, Fabisch created a figure taller than what Soubirous described, and with her head bent upward showing too much of her neck. Though the sculpture, completed in 1864, did possess some details described by Soubirous; such as, the Virgin’s hands folded in prayer, the blue sash around her waist, and a yellow rose on each foot, it showed a posture of docile obedience rather than empowerment, humility rather than authority.

The design for the Miraculous Medal with the brilliant rays of light emanating from Mary’s hands marked a feminine personification of spiritual agency new in Catholic art. The design for the Miraculous Medal was unprecedented on two accounts: first, for believers, the design was a mandate from the Virgin Mary herself, a mandate that satisfied a belief in Mary’s protection, solicitude, and assistance in every kind of endeavor or dilemma. Second, Labouré had reported the voice spoke to her, saying: "Have a medal struck after this model. All who wear it will receive great graces."[18] The medal, therefore was at once a totemic object and an image that spoke to women’s self-esteem. Popular devotion rather than doctrinal issues shaped its design and distribution, as well as shaped all subsequent representations of The Virgin Mary of the Miraculous Medal right up to the present time. Neither the design nor the distribution of the image of the Virgin of The Miraculous Medal were subject to episcopal control but instead they remained in the hands of the religious order of nuns to which Labouré was vowed. (To this day, that order, the Daughters of Charity, benefits from the sale of the medals.) With improvements in printing technology and color lithography, commercial publication of religious prints further removed any control of the ecclesiastical authorities concerned with formal representation of Marian teaching (fig. 8). Images modeling the iconography of Virgin Mary of the Miraculous Medal varied in composition, and titles were fluid. A stenciled-colored woodcut of 1856 is called Madonna of Blessings of Homes and Happy Families (fig. 9).

Literary Sources and Artistic Models

The representation of the Virgin as a powerful agent is not without precedent in Christian iconography. Earlier, the Valiant Woman had highlighted her assertive role.[19] The Valiant Woman described in the Book of Proverbs (31:10–31) is characterized as “a good and holy Hebrew woman” who held the title “Daughter of Zion” in the later prophetic literature and stood for Israel as a corporate entity. Christianity sought a corporate identity that could stand for the Church in a similar way, and the Virgin Mary inherited this role.[20] Long before the term Valiant Woman as an epithet of the Virgin reemerged in nineteenth-century religious culture, it was applied to Mary by the Fathers of the Church and the mystics of the Middle Ages.[21]As Marian theology developed over centuries, her image carried alternating traits of the Valiant Woman and the Immaculate Virgin.

The revolution of 1830 heightened ties between religion and left-wing politics and, not surprisingly, the Valiant Woman assumed attributes praised by social progressives, such as physical and moral strength, resourcefulness, trustworthiness, and fidelity.[22] In one example, Jean-François-Anne Landriot (1816–74), Bishop of La Rochelle, and later archbishop of Rheims, gave a series of seventeen lectures in 1862/1863 at the Cathedral of Saint Louis in La Rochelle on the topic of “The Valiant Woman,” which he addressed to the married women of his diocese.[23] Landriot intended to link the sacred and the secular spheres; that is, to link Mary—the holy Valiant Woman—with his female parishioners. The notion of the Valiant Woman as a model for Catholic French women continued well beyond the 1850s. Thérèse Martin of Lisieux (1873–97) a young Carmelite nun, earned the epitaph “valiant woman” shortly after her death from tuberculosis at age twenty-four. Witnesses claim that she did not complain about her agonizing illness, which she endured without medication.[24]

The story of Thérèse of Lisieux is relevant for another reason. In her autobiography, Thérèse described a pivotal moment in her faith that involved a statue of the Virgin Mary near her bedside table. The sculpture, dubbed “The Virgin of the Smile,” was a small scale replica of a work by Edme Bouchardon (ca. 1735; fig. 10).[25] Most works by Bouchardon (1798–1862) were destroyed during the Revolution of 1789 but remained known through engravings (fig. 11).[26] Bouchardon’s sculpture appears to be one of the first in this modern period to portray the Virgin Mary with her arms extended as if offering assistance or succor to those who gaze upon her.[27] Bouchardon’s Immaculata differed dramatically from better known Counter-Reformation paintings of the subject found in Spanish and Italian art (fig. 12).[28] In these images humility is the Virgin’s primary attribute and she is commonly shown with hands pressed together in prayer or folded against her chest.A bronze copy after Bouchardon’s sculpture was made during the reign of Charles X, ca. 1825, by Louis-Isidore Choiselat-Gallien (1784–1853), and distributed widely over a century or more to churches and chapels around France (fig. 13).[29] Aladel had access to the copy in the church of Saint-Sulpice located not far from the rue du Bac. (The sculpture can be viewed there today.)[30] Reliable sources claim that “It is this statue that Aladel presented to Vachette.”[31]

Works Inspired by “The Virgin Mary of the Miraculous Medal”

Natale Carta (1790–1884) created the Madonna of the Miraculous (1842;fig. 15) following the instructions of a twenty-eight year-old French Jew, Alphonse Ratisbonne (1814–84). While in Rome in 1842, Ratisbonne converted to Roman Catholicism after witnessing a miraculous apparition of Mary of The Miraculous Medal in the church of St. Andrea delle Fratte (figs. 14, 15). According to Ratisbonne, his eyes were drawn by a great burst of light, streaming from a little chapel. He saw the calm and compelling eyes of the Virgin Mary, who appeared to him for only a moment “exactly as she was represented on the Medal,”[32] with her arms extended and with rays of grace in the form of light that streamed from her hands. The Jewish convert had been given a Miraculous Medal the day prior to his vision and had been challenged to wear it and say a prayer dedicated to the Virgin Mary.Ratisbonne reportedly said, “If it does me no good, at least it will do me no harm.”[33] Carta’s painting shows the Madonna in a pronounced contrapposto stance, dressed in a pale rose dress and a blue mantle. Her left hand is turned upward and her right hand is pointing down, as arrow-like beams of light shoot downward from her fingers. The image differs from the medal both in the Virgin’s stance and in her expression. It strongly suggests that Carta knew earlier Italian examples of the Marian figure of the Immaculate Conception in which the Virgin bears the same sway of her hips, wears a spectacularly assertive expression, and extends her arms (fig. 16).[34] Yet another connection may have been the bronze-modeler Choiselat-Gallien, who made the replica of Bouchardon’s sculpture that Aladel saw in Saint-Sulpice, Paris. According to the ecclesial journal, L’Ami de la Religion, Choiselat-Gallien was highly regarded as a creator of religious art, well-known to the Roman hierarchy, as well as having had meetings with Pope Gregory XVI (1765–1846). Because the priests of the Jesuit order in Rome were familiar with the modeler as well as responsible for organizing Ratisbonne’s reception into the Catholic Church, it is possible that they were responsible for the commissioning the painting by Carta.[35] The Roman clergy would have been familiar with Choiselat-Gallien's famed replica of the Bouchardon’s work.[36]

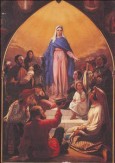

A number of subsequent paintings combine elements from The Miraculous Medal and Carta's painting of The Virgin of The Miraculous. Among them is a painting by Antoine Rivoulon (1810–64) entitled Litanies of Our Lady (fig. 17), which was exhibited at the Salon of 1846 and, two years later, published as a lithograph that became widely popular. [37]In Rivoulon’s painting, today in the Cathedral in Vannes, the Virgin has rouged cheeks and red lips that give her a worldly allure. The standing figure, with arms and hands extended, gracefully sways, and the blue and rose drapery accentuates the curve of her thigh. Her gaze is directed toward the viewer with an expression that is reminiscent of a photographer’s model. Rivoulon’s Madonna is more modestly dressed than the figure painted by Carta and wears a simple veil rather than a gold crown. But, like Carta’s painting, it portrays an active and self-possessed figure, expressing those traits that are characteristic of Christ in his role as intercessor and consoler. Both paintings may be compared with Dominque-Louis Papety’s (1815–49) Madonna of Consolation, shown in the Salon of 1846, in which the figure of the Virgin Mary, who is active as an intercessor for petitioners, appears to replace the figure of Christ in that role. Indeed, Papety’s composition closely resembled a well-known work by Ary Scheffer from 1837, entitled Christ the Consoler (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam).

Historical Moment

The first apparition of the Virgin Mary to Labouré occurred shortly before the July Revolution of 1830, at a time when the Restoration regime of Charles X was near collapse and the archbishop’s palace was raided. For some, the reports of the Marian apparitions were a cause for national pride as these miraculous events enhanced the prestige of the French Church and the French State among other predominantly Catholic nations.[38] Skeptics and anti-clericals suggested that Labouré may have suffered from hallucinations.[39] Her biographers claim that Père Aladel heard of the visions with great skepticism and tested the narrative of instructions and promises by the Virgin Mary over a long period. He conferred with a fellow priest before submitting the narrative to the archbishop.[40] It is beyond the scope of this paper to offer a psychological analysis of Labouré, her background, and her exposure to social influences. Yet, quite apart from an estimation of Labouré’s state of mind or a conclusion about her susceptibility to pressures, the evidence of the huge number of reports of cures and conversions of those who wore the medal led to a tremendous devotion to Mary as a woman of powerful agency.

One indicator of the medal’s power to galvanize solidarity among women was the surge in devotional confraternities composed exclusively of women. The Miraculous Medal was the emblem of the archfraternity (cluster of confraternities) of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires, which was founded in 1836 and grew to 640,000 members by 1845.[41] Research by historians of women’s emancipation in France has borne out that early emancipation efforts in France received support from the Church.[42] Claire Goldberg Moses has shown that French feminist goals, early on, were aligned with Catholicism, as they shared important concepts such as charité (goodwill) and universal brotherhood/sisterhood. Writes Moses, “They shared a Christian language of human rights, thus the Church was seen by some feminists as an ally.”[43] Among the progressive movements, followers of socialist philosopher François-Marie-Charles Fourier inspired women to contemplate new modes of participation in the social discourse. The Saint-Simonians (admirers of utopian socialist Comte de Simon 1760–1825), founded the journal La Femme Libre in 1833; theyorganized a “new Christianity” promoting the revolutionary idea that God was both male and female. In addition, the inimitable activist, Flora Tristan, sought to challenge the subjection of women and to elevate their status. Labouré’s vision of the Virgin as a figure of powerful agency may be considered in this socio-political context. In the words of Richard D. E. Burton, “The phenomenon [of the apparitions of the Miraculous Medal] must be understood as part and parcel of the critical years of 1830–34, which Parisians would refer to as 'the time of the riots.’”[44] Burton makes a convincing case for the convergence of political, social, and ecclesial circumstances surrounding the appearance and diffusion of The Miraculous Medal.[45]

Popular Prints and Conventional Symbols

Neither theology nor feminism, but mechanization was at the root of unprecedented notoriety of the image of the Virgin Mary of The Miraculous Medal (figs. 18, 19). Inexpensive to produce and easily distributed, medals and prints initiated a Catholic art form that was especially supportive of Marian devotion. The transmission of an active Marian figure through portable objects—first medals, then colored prints—allowed the notion of potent female figure to spread. All through the nineteenth-century, however The Valiant Woman, strong in faith and physique, was counterbalanced by the Virgin Mother who is faithful, humble, obedient, and pure. The flexibility of posture and pose and the binary symbolism attached to Marian images held fast during this period of conflict between ecclesial factions in France and Rome. A good illustration of this apparent co-existence for the portrayal of Marian virtues can be seen in another sculpture by Fabisch that was completed six years before his commission to represent Soubirous’s vision at Lourdes. Rather than the classical pose of 1864, the Virgin Mary’s open arms and downward gaze appear nearer the figure on the Miraculous Medal (fig. 20).[46]

The Virgin Mary was sometimes represented with her arms sharply bent at the elbow and hands pressed together; sometimes with arms splayed and opened palms, while other images show her arms slanted downward at a forty-five degree angle or sloped to a much narrower angle from her body that gives the figure a constrained pose. Some versions display long shards of light emanating from her hands, sometimes half-beams of light, or sometimes no light at all. Starting in the early twentieth-century, artists began showing rays of divine light no longer as emanating from Mary, but from her Son Jesus.[47]

Conclusion

The subject of the Virgin Mary of the Miraculous Medal has continued to inspire artists internationally into the twenty-first century. A 1929 woodcut by Eric Gill, titled Our Lady of Lourdes, renders the Virgin with rays of light coming from her downward-slanting hands. However, it was only in Labouré’s visions in Paris that the Virgin Mary displayed rays of light emanating from her hands; an image never claimed to have been seen at Lourdes. Different from traditional images of Mary of the Miraculous Medal, in Gill’s image the rays seem to spill from her without her agency or will (fig. 21). She appears as an empty vessel or a spout from which the powerful divine light illumines everything below. A 2006 image of Immaculate Mary by David Gregory Taylor brings a far different vision of Mary of the Miraculous Medal as a robust figure with open palms that shoot rays of light toward the viewer (fig. 22). The definitive quality of Mary on the Miraculous Medal is that of a woman who possesses powers of her own in conformity to a feminist ideal. Over the centuries, Mary has been an emblem of maternal care, a model servant of God, and a mediatrix between man and God.[48] The image of The Virgin Mary of the Miraculous Medal satisfies a wider audience than any other single Marian image because it offers feminine power as well as compassion, in addition to an unparalleled proximity to divine assistance.

I thank the librarians and staff at Columbia University’s Samuel P. Avery Art and Architecture Library for their generous assistance, as well as M. Michel Portal and Père Pierre Descouvemont in Paris.

[1] Quoted in Paul Thureau-Dangin, L’Eglise et l’état sous la monarchie de juillet (Paris: Plon, 1880), 14–15.

[2] The minutes of the episcopal inquest on the Miraculous Medal apparitions are included in the book by René Laurentin, Vie de Catherine Labouré (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer, 1980), and an English edition, Catherine Labouré Visionary of the Miraculous Medal (New York: Pauline Books, 2006).

[3] “The archbishop so strongly believed in the message of the Virgin Mary as reported by Labouré, he urged this devotion upon his people through a series of pastoral letters; he consecrated himself and his diocese to the Immaculate Conception.” Thomas I. Dirvin, Saint Catherine Labouré, of the Miraculous Medal (New York: Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, 1958), 114.

[4] Ibid., 115. Also cited in Jean-Marie Aladel, The Miraculous Medal: Its Origins, History, Circulation, and Results, trans. “P.S.” (Philadelphia: H. L. Kilner & Co.,1880; repr., Fitzwilliam, NH: Loreto Publication, 2005), 58. Citations are to the reprint edition.There are a number of these first-struck medals at the Mother House of the Daughters of Charity on the rue du Bac. In addition, the US shrine of The Miraculous Medal, located in Philadelphia, has one of the originals in its museum.

[5] Aladel, Miraculous Medal, 58–59.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Laurentin, Vie de Catherine Labouré; citedin Richard D. E. Burton, Blood in the City: Violence and Revelation in Paris 1789–1945 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001), 118–27.

[8] Dirvin, Saint Catherine Labouré, 104.

[9] Ibid., 100.

[10]O Marie, conçue sans péché, priez pour nous qui avons recours à vous.

[11] Aladel, Miraculous Medal, 49. Labouré described the design of the back view of the medal as a cross on a horizontal beam upon which is the letter “M”; both the cross and “M” are surrounded by twelve tiny stars. The letter “M” is situated above two hearts of smaller size; one is encircled with a "crown" of thorns and the second is a heart pierced with a sword. The iconography is adapted from well-known Gospel verses that traditionally linked the suffering of the Mother Mary to the Son, Jesus (Lk. 2: 34–35; Matt. 27:29; Mark 14:17; John 19:1).

[12] Aladel, Miraculous Medal, 49–51.

[13] Thomas I. Dirvin, C.M. (Congregation of the Mission, a vowed order of priests and religious brothers associated with the Vincentians who claim their patron as St. Vincent de Paul). Dirvin is citing Chevalier’s official deposition. Dirvin had access to archives of all the inquiries about the apparitions, the Miraculous Medal, and other unpublished material.

[14] Laurentin, Catherine Labouré Visionary, 146.

[15] René Laurentin, Bernadette Speaks: A Life of Saint Bernadette Soubirous in her own Words,trans. John W. Lynchand Ronald Desrosiers (Boston: Pauline Books, 2000): 222–28.

[16] Francis Trochu, Saint Bernadette Soubirous, trans. John Joyce (Rockford: Tan Books) 1957), 234–35.

[17] Laurentin, Bernadette Speaks, 113.

[18] Aladel, Miraculous Medal, 49–50.

[19] The Valiant Woman shares the character of theShulamite Woman (alternatively known as the Sulamite Woman or Sulamith) who is described in the Wisdom Books of the Hebrew Bible: the Book of Proverbs and in The Song of Songs. In Christian texts she is addressed as a symbol of Synagoga or Ecclesia, that is as “the Bride” figure and as the precursor to Mary.

[20] Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Daughter Zion, trans. John M. McDermott (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1983): 21–29.

[21] Fathers of the Church refers to writers whom the Church recognizes as her special witness of the faith based on theologies they developed in the early centuries of Christianity.

[22] The most vocal of the socialist theorists were the Saint-Simonians led by Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825) and the Fourierists, led by Francois-Marie-Charles Fourier (1772–1837). Another important voice for women’s rights in the public sphere was Flora Celestine-Thèrese-Henriette Tristan (1803–44). Barthélemy-Prosper Enfantin was the devoted follower of Saint-Simon who led the movement after Saint-Simon’s death. Susan K. Foley, Women in France since 1789: The Meaning of Difference (London: Palgrave, 2004), 254.

[23] Jean-Francois-Anne Landriot, The Valiant Woman: Conferences addressed to the Ladies Living in the World, trans. Alice Wilmot Chetwode (Dublin: H.W. Gill, 1886).

[24]The Story of a Soul, the autobiography of Thérèse Martin, revealed a capacity for physical suffering that was seemingly beyond human endurance and would appear to be counter-cultural, except for the fact that over twenty-million copies of her autobiography were printed by 1925 and translated into sixty languages; today, she is greatly admired in Muslim, Jewish, and Christian cultures.

[25] The title, Virgin of the Smile, was adopted almost immediately from the date of the publication of the autobiography of Thérèse of Lisieux in 1898. In her book she described how the figure smiled at her. Edme Bouchardon, considered one of the eighteenth-century's greatest sculptors for his classicizing style at a time when the Rococo style was dominant, worked in Rome from 1723 to 1732.

[26] Alphonse Roserot, Edme Bouchardon (Paris: Librairie Centrale des Beaux-Arts, 1910), 1; and Edme Bouchardon: Sculpteur du Roi 1698–1762, Exposition du bi-centenaire (Chaumont: Musée de Chaumont, 1962).

[27] There is a painting by Zurbarán (1661, Szepmuveszeti Muzeum, Budapest) that shows the figure with arms languidly extended and palms open, powerless and gazing upward appealing to the Godhead. It is quite different in form and meaning from Bouchardon’s work.

[28] The subject of The Immaculate Conception is based on several books of the Old Testament such as Ecclesiastes, 24:17, Wisdom, 7:26, and the Song of Solomon, 6:13, in which she is described as “a garden enclosed,” Virgin pura (pure), and the “speculum sine macula” (the spotless mirror). It was the Spanish painters in the seventeenth century, who were commissioned to add new iconography to the immaculist image to better explain the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception. Thereafter, Spanish artists conflated the concept of Mary Assumed into Heaven and crowned by the Trinity and Mary Immaculate posed standing on a crescent moon as The Apocalyptic Woman.The subject of the Apocalyptic Woman is based on narrative details about the unnamed woman from the Song of Songs and the Book of Revelation 12:1 also known as Apocalyptic literature.

[29] Publicity brochure published by Paroisse Saint-Sulpice (2000). Its text is based on Charles Hamel, Histoire de l’eglise Saint-Sulpice (Librairie Victor Ledoffre, 1900).

[30] I thank M. Michel Portal and Père Pierre Descouvemont who provided copies of documents located in Paris. Bouchardon’s sculpture, originally of massive proportions and made of silver, was copied in a more modest size and given the title, The Blessed Virgin Greeting the Angel of the Annunciation,according to the Paroisse Saint-Sulpice brochure.

[31] Pierre Descouvemont, considered the authority on the life of Thérèse of Lisieux and the sculpture of The Virgin of the Smile, makes the claim that this is the version by Bouchardon that Aladel saw in the church of Saint-Sulpice. Pierre Descouvemont and Helmut Nils Loose, Thérèse of Lisieux (Montreal: Novalis, 1996).

[32] Alphonse Ratisbonne, A Nineteenth-Century Miracle: The Brothers Ratisbonne and the Congregation of Notre Dame de Sion, trans. L. M. Leggatt (London: Burns Oates & Washbourne, Ltd., 1922), 78. Also reported in Dirvin, Saint Catherine Labouré, 169; and Natalie Isser and Lita Schwartz, “Sudden Conversion: The Case of Alphonse Ratisbonne, “Jewish Social Studies 45, no. 1 (Winter 1983): 17–30. Ratisbonne’s social stature made his conversion at the appearance of Mary of the Miraculous Medal the center of attention for the Church hierarchy and the elite bourgeoisie.

[33] Ratisbonne, A Nineteenth Century Miracle, 77.

[34] Details of the drawing are very similar to Natale Carta’s composition and to those of two Italian Baroque artists: Jacopo Foschi’s composition of 1546, and Pier Francesco Foschi’s Dispute of the Immaculate Conception ca. 1530–40. Muir Wright analyzes the images by Jacopo Foschi and Pier Francesco Foschi and their representation of Marian dogma. Rosemary Muir Wright, Sacred Distance: Representing the Virgin (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006).

[35] St. Andrea delle Fratte is a church under the guidance of the Minimi Friars, members of the religious order founded by St. Francis of Paula, who are characterized by their special dedication for humility. However, the prelates surrounding the conversion of Ratisbonne, which included reception of sacramental rites of Baptism, Confirmation, and Eucharist, were organized by the Jesuit order including the Superior General of the Jesuits. The Roman episcopate considered Ratisbonne’s social standing and his conversion highly significant and relied on the Jesuit priests to organize the rites of conversion. In consideration of Ratisbonne’s nationality, the Superior General of the Jesuits called to Rome the famed French archbishop Félix Dupanloup (1802–78) to offer additional support. It was Dupanloup who heard the deathbed conversion of the French statesman, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (1754–1838). It is likely that the Jesuits organized the commission for Carta to paint the Madonna of the Miraculous.

[36] Alrich Le Clere, “Nouvelles Ecclésiastiques,” L’Ami de la Religion: Journal Ecclésiastique, Politique et Littéraire, August 9, 1834 (Paris: Librairie Ecclésiastique, Le Clere et Cie., 1834), 81:68.

[37] Brigitte Nicholas, Autour de Delacroix: La Peinture Religieuse en Bretagne au XIXe Siècle, exh. cat. (Vannes: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1993), 126.

[38] Thomas A. Kselman, Miracles and Prophecies in Nineteenth-Century France (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1983), 76. David Blackbourn has observed that anti-French feeling intensified in Germany because of the obvious material success inherited by the sites of Marian apparitions. David Blackbourn, Marpingen: Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in a Nineteenth-Century German Village (New York: Vintage Books, 1995), 145.

[39] Michael P. Carroll, The Cult of the Virgin Mary: Psychological Origins (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986).

[40] Aladel’s 1834 publication of The History of the Miraculous Medal described the apparitions in a narrative of ninety pages; by the eighth and last edition in 1842, it contained 608 pages and included hundreds of testaments of the transformative cures and conversions among those who wore the medal with faith. Dirvin, Saint Catherine Labouré, 162.

[41] Organizations of women have been proliferating since the late 1830s. James Francis McMillan, "Religion and Gender in Modern France: Some Reflections," in Religion, Society and Politics in France Since 1789, ed. Frank Tallett and Nicholas Aikin (London: Hambledon Press, 1991), 92–93. “The Archconfraternity of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires numbered twenty million associates, and 15,000 affiliated confraternities.” Barbara Corraro-Pope, “Immaculate and Powerful: The Marian Revival in the Nineteenth Century,” in Immaculate and Powerful: The Female in Sacred Image and Social Reality,ed.Clarissa W. Atkinson, Constance H. Buchanan, and Margaret R. Miles (Boston: Beacon Press, 1985).

[42] The list of authors on this subject is too long to represent here; some sources are: Harriet B. Applewhite, and Darline G. Levy, eds., Women and Politics in the Age of Democratic Revolution (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1990); Edward Berenson, Populist Religion and Left-Wing Politics in France, 1830–1852 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984); Christine Faure, Democracy Without Women (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991); Susan K. Foley, Women in France since 1789: The Meaning of Difference (Melbourne: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004); Karen Offen, European Feminism 1700–1950: A Political History (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000); Madelyn Gutwirth, Avriel Goldberger, and Karyna Szmurlo, eds., Germaine de Stael: Crossing the Borders (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991); Susan K. Grogan, French Socialism and Sexual Difference: Women and the New Society, 1803–1844 (New York: Macmillan, 1992).

[43] Claire Goldberg Moses, Feminism, Socialism, and French Romanticism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993).

[44] Burton, Blood in the City, 118–29.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Fabisch received a commission for the Chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Fourvière, Lyon, in 1852, to mark a seventeenth-century event in which it was believed that The Virgin Mary saved the city from disease. Fabisch relied on medieval representations of The Virgin Mary as the queen of heaven and wearing a crown. Fabisch’s figure remains the definitive model for the Virgin of Lourdes in popular art with innumerable replicas in a variety of media and materials.

[47] Ecclesial authorities revised the liturgy (sequence of prayers of the Church) transferring agency from Mary to her Son, Jesus Christ. Readings from Proverbs 8 were replaced by verses in Genesis 3:9–15 and 20, in which it is proclaimed that the seed of the woman will crush the serpent, whereas in previous readings, the heel of the woman will crush the serpent. The redirected Biblical texts become evident in the popular art. For example, in 1931 theophanic revelations inspired a narrative not unlike the one recorded by Labouré a century earlier, as a Polish nun, Sister Faustina Kowalska (1905–38), reported apparitions of Jesus and that he directed her to have his image painted with beams of light emanating from his heart.

[48] Doctrinal controversies also included a declaration of heresies that argued for Mary as co-Redemptrix of mankind.