The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Artworks, as many of them are called without actually being so, have been arriving by the thousands, especially paintings so that, three months ago, the moment came when there was approximately one work of art, highly priced, for every forty residents in the city, including breastfeeding infants and the abject poor. Right away, there emerged artworks of minor value, which were sold at once to the people, so that by the same calculation there would be a picture or a sculpture even for every cat. This is by no means an exaggeration if one takes into account the exhibition we have had and still have, which, alone, features more than twelve hundred objects, of which eight hundred are paintings.[1]

The above quotation appeared in 1888 in La Nación, the most prestigious newspaper of Buenos Aires. Despite its sardonic and playful tone, it revealed an important fact: by 1888, the capital of Argentina was flooded by artworks fetching high prices on the art market. The reporter’s numbers may have been exaggerated, if one takes into account that Buenos Aires, according to the Municipal Census of 1887, had 433,375 inhabitants.[2] If every 40th inhabitant owned an artwork, there would have been at least 10,000 of them offered for sale. While this number seems high (it is impossible to check its accuracy), it is nonetheless safe to say that in the late 1880s there was an unparalleled influx of paintings and sculptures into Argentina’s capital. Furthermore, the impact that exhibitions such as the one mentioned at the end of the article had on the public must also have been substantial. The reporter is referring to a gathering of twelve hundred works of French art exhibited in a space prepared ad hoc in a department store along Florida Street, the most elegant artery of the city.

The purpose of this article is to look at the circumstances that led to this affluence of artworks in Buenos Aires from the late 1880s until the mid-1910s. I will argue not only that Buenos Aires was unique in Latin America for featuring an international art market, but also that this phenomenon can be explained by a number of singular circumstances, including the late foundation in Argentina of public art institutions, the parallel development of private art collecting, and the establishment of a receptive market for European art. Academic and modern (Realist, Impressionist, veristas, and Symbolist) artworks from France, Italy, and Spain could all be found in the city and were purchased by local buyers. Some of them would eventually end up in the collection of the National Fine Arts Museum.

In the first three sections, I focus on the material conditions that allowed the emergence of a market for foreign art in Buenos Aires. To prove Buenos Aires’s differential character, I observe the creation of artistic institutions and compare them with simultaneous cases elsewhere in Latin America. I also deal with the establishment of the first art dealers in the city and follow the strategies and type of artworks they introduced to this new art public. The fourth and fifth sections of the article cope with the alliances established between foreign galleries and local ones, as well as the purchases made by Argentinians in well-known Parisian houses, such as Boussod, Valadon & Cie. These acquisitions also constitute a unique feature and introduce us to the analysis of two prominent Argentinian private collections (Guerrico’s and Lorenzo Pellerano’s), clear examples of the first European art collecting that took place in Buenos Aires. Finally, I center on the strategies developed by the French state in order to build an art market in the Argentinian capital. I look into important groups of paintings and sculptures sent by French agencies and acquired by public and private local collectors in the first years of the 1900s. These artworks were favored among private buyers and shaped the collections of the National Museum of Fine Art and, as examined at the end of my article, led to complaints by Argentinian artists who felt they did not have a receptive audience for their productions.

The Financial Boom in Nineteenth-Century Argentina, Rastacueros, and Art Collecting

During the administration of Mayor Torcuato de Alvear (1880–1887),[3] Buenos Aires, which in 1880 had become the capital city of Argentina, saw the beginning of a bold urban transformation (fig. 1). Avenues and plazas were opened up, streets were paved, public buildings were erected, and the elite built opulent houses (petits hôtels), in various eclectic styles.[4] Multiple factors hastened this modernization project, but foremost among them was that between 1880 and 1914 the Argentine economy experienced exponential growth due to its insertion into an international market as a major exporter of raw materials. This economic boom led to the rise of a wealthy and powerful upper class largely composed of owners of cultivable lands, who controlled the financial networks and held strategic positions in the public sphere. The spectacular urban development of Buenos Aires garnered the city its nickname as the “Paris of South America” (fig. 2). This title reflected material changes that were taking place in the city and the consumption patterns and behaviors of the upper class.

An annual trip to Europe, with stays in Rome, Madrid, and, mainly, Paris, was a “must” for members of the Argentinian bourgeoisie.[5] These cities were the places to go to renew one’s wardrobe, attend the theatre season, and see and purchase works of art. Undoubtedly, the purchasing power of Argentinians had an impact on the European market, an impact that first registered in the form of astonished and satirical accounts but soon led to the realization on the part of merchants of luxury goods and art dealers of the concrete possibility of a new “outlet” for the production of European artistic workshops. Indeed, the new buying power of Buenos Aires’s powerful bourgeoisie caused the relocation of European artists as well as commercial agents to Buenos Aires, looking for new markets.[6]

The presence of rich South Americans in Europe led to the birth of a new satirical figure, created in Europe around 1880. It was the rastacuero, a nickname for the Latin American bourgeois who had recently acquired wealth but whose affluence did not correspond with competency in questions of education, taste, and social rituals. This image circulated in fin-de-siècle European literature and the press and eventually made its way back to Argentina. By the elitist standard of many European writers, the rastacueros, “poorly polished” rich men, were laughable, as they did not know how to behave or what to consume among the unlimited luxury goods offered by the European metropolis.[7]

A comparison between the interiors of the wealthy porteña[8] homes at the end of the nineteenth century and those painted or described some decades earlier presents stunning differences. The austerity and simplicity of early nineteenth-century stately residences, still influenced by the way of living during the viceroyalty (fig. 3), gave way to luxury and opulence.[9] The devotional pieces (Virgins, Christs, and saints) that, with family portraits, were once the only artworks found in these residences were now moved to religious buildings.[10] The houses of the high society started to be crowded with bibelots, clocks, mahogany furniture, framed engravings and chromolithographs, and some paintings, mainly signed by contemporary European artists (fig. 4).

Private Initiatives and Absence of Art Institutions

Before discussing the artistic commerce that developed in Buenos Aires from 1880 onward, with its antecedents in the previous decade, one must note that the city did not have an official art academy or a national museum until the end of the century. Its National Academy of Fine Arts (Academia Nacional de Bellas Artes) was not established until 1905,[11] and its first art museum, the National Museum of Fine Arts (MNBA) was created by presidential decree in 1895 and opened a year later in the Bon Marché, a department store located on Florida Street. Until then, access to artworks was not mediated by the state but by commercial agents (art importers and gallery owners) and private collectors. Argentinian artists were scarce. They were united in a self-promotional association, the Sociedad Estímulo de Bellas Artes, founded in 1876 with the objective of providing art classes for students. Created by artists and amateurs, it received some financial support from the State, but was poorly professionalized, and artists teaching there were unpaid.[12]

The place of the arts in Argentina differed radically from that elsewhere in the Americas, where academies functioned as sites of permanent art exhibitions in addition to serving as places of training and professionalization of artistic activity. These were the roles of the San Carlos Academy, the first art academy founded in the Americas, in México City, in November 1784, following the model of the Academy of San Fernando of Madrid.[13] While the Mexican academy witnessed hard times throughout the civil wars, it was reorganized in 1847. In the following year, it began to arrange annual shows for students and scholarship holders.[14] Something similar happened with the Academia Imperial do Belas Artes, created in Rio de Janeiro in 1826 under Pedro I. From the beginning, this institution held a permanent exhibition of works by teachers and students and in 1840 set up a system of “General Exhibitions of Fine Arts” with the aim of showing students’ results and contributing to public education in artistic matters. Some of these exhibitions, especially those organized in the late 1870s, were massive affairs, visited by a large number of the local population, which showed particular interest in history paintings praising heroic deeds.[15] In Santiago de Chile, the Academy of Painting was founded in 1849. This project, as demonstrated by recent research, was simultaneous with the formation of a museum of painting, the Academia de Pintura, which housed the works used by students as models and exhibited the first productions of national artists.[16]

Nothing of this sort existed in Argentina. As reported in an article in 1888: “The government has not yet paid serious attention to the great artistic movement that is developing and now asks for the help of an academy or museum.”[17] In the absence of such institutions, public exposure of works of art was provided by merchants, initially in so-called bazaars—general stores that offered bronzes, marbles, pictures, and curios among other articles on sale—and later in the first professional art galleries that were founded in the city. Private collectors also tried to compensate for the absence of art institutions. The first collectors lent their artworks to exhibitions organized with charitable aims and, in so doing, made them accessible to the public. Moreover, residences were often open to amateurs and art students. These “casas museo,” as they were called in their time, permitted public contact with what was then considered high art, that coming from Europe that suited the bourgeois tastes shared by purchasers and spectators. Landscapes and scenes of rustic life, portraits, nudes (generally academic displaying mythological subjects), and the so-called casacón paintings (detailed genre scenes situated in historical settings) reached the country, forming a unique corpus of nineteenth-century European art.

The Rise of the Art Market in Buenos Aires

There is no doubt that in these last ten years, an extraordinary taste for art has developed among us. Whether this is due to the trips to the Old World, so much in fashion at this time, or to the introduction in the country of some important, albeit few, artworks; or whether this is a natural phenomenon that was bound to happen during the current age of opulence which could be nothing less than favorable for art: certainly for any of these principal reasons we count today on Buenos Aires hosting a certain number of art galleries that have no reason to envy private collections of modern artists’ works formed in Europe. In quantity perhaps ours are inferior; in terms of quality and the importance of the signatures featured on the pictures, ours are certainly at the same height.[18]

This quotation from the newspaper La Prensa applauded the presence in Buenos Aires of a true art scene in the 1890s, thanks in large part to the galleries founded by private collectors. The various elements that fostered this phenomenon are mentioned in the quotation: the voyages to Europe, the preference for “modern artists’ works,” and the import of foreign pieces with the objective of selling them in Buenos Aires. They were brought by diverse middlemen; some were professional art dealers, antiquarians, or artists, but most were store owners. Indeed, upon their arrival, artworks were offered for sale in bazaars, furniture stores, bookstores, art supply stores, and even corner stores.[19]

Initially, most imported art was Italian, as Italian immigrants were among the first to dedicate themselves to artistic commerce in the city. The work of editor Angelo Sommaruga (1857–1941) provides an outstanding example. Exiled from Italy for political reasons, Sommaruga devoted himself to the organization in Buenos Aires of exhibitions of his Italian friends, with a strong presence of verismo. Featured in these exhibitions were works by leading artists, including Giacomo Favretto (1849–87) and Francesco Paolo Michetti (1851–1929). The taste for works by the latter was so prominent on the Argentinian art scene that poet Rubén Darío (1867–1916) claimed that forgeries of Michetti’s paintings were being made in Buenos Aires.[20]

The first, mostly Italian, dealers were also responsible for offering paintings attributed to old masters, including works that allegedly were executed by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618–82), Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), and Paolo Veronese (1528–88). The presence of such celebrated names points to the phenomenon of “attributionism” seen by Francis Haskell and Carlo Ginzburg as characteristic of the nineteenth century.[21] Yet, as critics rightly noted, Argentinian buyers soon caught on and learned to differentiate between originals and imitations and to “distinguish the work of a dauber from that of a great artist.”[22]

While the Italian merchants active in the last quarter of the nineteenth century brought only a smattering of non-Italian art to Buenos Aires, the establishment of art galleries in the last years of the century led to a rapid increase in the import of Spanish and French contemporary art. Indeed, as the twentieth century approached, the art market started to professionalize. Among the first professional art galleries was the renowned Galería Witcomb, a traditional photography studio of the Buenos Aires elite that set up one of its rooms for the trade of paintings and sculptures in 1897 (fig. 5). There was also the bazaar of Francesco Costa, which was transformed into an art gallery in the first years of the new century (fig. 6). These spaces were close to each other on the elegant and bustling Florida Street within the city center—Witcomb on Florida 364 and Costa on Florida 163. French, Italian, and Spanish contemporary art would prevail in the shows these galleries organized, although the presence of the arts of previous periods as well as the work of Argentinian artists also began to be celebrated in some individual and collective shows at these same sites.[23]

However, what characterized the Argentinian art scene most during this period was the presence of foreign dealers—predominantly Spanish, Italian, and French—who traveled to Buenos Aires with the aim of promoting paintings and procuring clients among the upper classes. These foreign dealers appealed to the nostalgia of rich immigrants and their need to connect emotionally with their homeland. Some of these dealers were independent; others were connected with, or served as agents of, important art dealers active in Europe, especially in Paris.

Based in Buenos Aires, some dealers, such as the Italian Ferruccio Stefani (1857–1928) and the Spanish José Pinelo (1861–1922), sought to consolidate a regional market. Stefani organized exhibitions in Valparaiso, Chile; Montevideo, Uruguay; and Rio de Janeiro. Pinelo sent works to Argentinian provincial cities—Córdoba and Rosario—and to the main Brazilian centers, Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo, between 1911 and 1914.[24]

Between Paris and Buenos Aires

Before discussing the foreign, especially French, dealers and middlemen[25] in Buenos Aires in more detail, it must be stressed that, despite the establishment of art galleries in Buenos Aires, the trips to Europe to buy artworks continued. The tour to Old World capitals had been a common practice among local elites since the 1860s, but by the end of the century, the architectural reforms carried out in the port of Buenos Aires made the entry and exit of ships even easier. Ships became increasingly luxurious, and the duration of the journey to Europe was reduced to an average of fifteen days.[26] Rich families moved to Europe for weeks or even months, with Paris as their main destination. Many sold their furniture and paintings at auction prior to every trip, taking advantage of the European stay to renew them.[27] The acquisition of luxury objects, including fashionable clothes, was the main goal of these journeys. For example, the well-known Parisian couturier Worth did so much business with Argentinians that, by the mid-1890’s, the installation of a branch was proposed in Buenos Aires. To Argentinians, such propositions demonstrated the “faith that our financial future inspires abroad.”[28]

The European trip was also an opportunity to come into direct contact with “great art,” whether during visits to museums, annual salons, or universal exhibitions, and it provided an effective occasion to purchase artworks. Well-known galleries, such as Georges Petit and Boussod, Valadon & Cie, were frequented by the Argentinian elite, as were the auctions at Hôtel Drouot.

It is important to distinguish between the purchases made in Paris during the last quarter of the nineteenth century by collectors who went there, and the more numerous acquisitions made at the beginning of the twentieth century in Buenos Aires through agents or middlemen working for French galleries. Few, if any, French galleries established branches in Buenos Aires, but many sent agents who organized exhibitions for them in the Argentinian capital. Indeed, middlemen, working for dealers, individual artists, or artists’ societies played a key role in the sale of French art to Argentinian clients.

This article will focus on Boussod, Valadon & Cie, as to which there is much available information, thanks to the Goupil & Cie/Boussod, Valadon & Co. stock books at the Getty Research Institute, which have been digitized and are available online.[29] Research based on these stock books clearly bears out the power of Argentinian art consumers, as the books record the activity of forty-seven purchasers from Buenos Aires who bought, between 1886 and 1913, two hundred and thirty-four works destined for their homes or for resale in the local market.[30] These numbers surpassed by far the transactions of purchasers from other booming cities of the region; for example, sixteen buyers from Santiago de Chile, who obtained a total of twenty-six works; fourteen customers from Sao Paulo with a total of twenty-three transactions; and seven Rio de Janeiro clients who made thirteen acquisitions. It is noteworthy that there is no indication of buyers from Mexican cities.

Men like César Cobo Ocampo, Emilio Furt, Manuel Güiraldes, Emilio Lernoud, Francisco Llobet, Lorenzo Pellerano, and members of the Guerrico and the Santamarina families,[31] whose names mean little to European or American art historians, were the main Argentinian collectors of the turn of the century.[32] All of them acquired works that came from Boussod, Valadon & Cie, and many of their purchases eventually would become part of the national collection. In addition to these collectors were other members of the local elite like Carlos V. Ocampo, José Pacheco Anchorena, Anchorena-Ortíz Basualdo, Antonio Devoto (fig. 7), Alejandro Estrogamou, and Gastón Fourvel-Rigolleau, who bought art for their homes but did not collect with a particular institutional projection (i.e., they did not generally exhibit, lend, or donate their belongings).

Also, French painter Tristán Lacroix (1849–1914), active in Argentina from the end of the nineteenth century, bought nineteen pictures from Boussod, Valadon & Cie to be sold in the local market. They were mainly Barbizon School landscapes, a genre that had an unquestioned prominence in local collections. Other purchasers bought pictures primarily to give to institutions. Among them was Pedro Luro, who acquired works for one of the principal spaces of sociability for the local elite, the Jockey Club.

Two purchases for the MNBA also appear in the registries of Boussod, Valadon & Cie. The first was made in 1909 by the director of the National Commission of Fine Arts, José Semprún, while the other was arranged in 1911 by J. (Joseph) Allard, who since 1907 had acted as the provider of European works for the collections of the recently created museum.

Allard, who had a Parisian gallery at 20, rue des Capucines, was among the French art dealers most active in Buenos Aires. He planned ten exhibitions in Buenos Aires between 1907 and 1914, mentioning—at least in five of them—his alliance with Boussod, Valadon & Cie from Paris. Most of these shows took place at local art galleries: the Costa Salon and at the Philipon Salon. For his services, Allard retained 50% of the sale price (fig. 8). Allard organized group exhibitions of French and other foreign art, two exhibitions of the French Watercolor Society, and one solo show of Émile René Ménard (1861–1930) held in 1913.[33] These exhibitions were well-received by critics, who praised the quality of the European works, applauded the increasing number of visitors, and highlighted record sales, as at the exhibition of 1909, where sales reached the impressive amount of 200,000 francs.[34]

Jean Mancini (18?–1920), another French dealer active in Argentina, traveled many times to Buenos Aires with the purpose of arranging exhibitions with works of Boussod, Valadon & Cie (his name is linked to at least sixty-five transactions) and of other commercial galleries with a presence in Buenos Aires, like Georges Petit’s gallery. He also took part in enterprises headed by the French State.[35] The catalogues of the exhibitions organized by Mancini were written in French by the critic Léon Roger-Milès (1859–1928), who admired Mancini as a crusader for making French painting known beyond the Atlantic: “It is with joy that I have seen Mancini enlisted among the brave pioneers who will preach in Argentina how Beauty is conceived by the French School.”[36] Roger-Milès praised the work of this “ambassador of French art,” who promoted art that was “healthy, robust, fertile, capable of offering an example” and avoided the “bad fever of fake innovators and fake genius.”[37]

The cooperation of Boussod, Valadon & Cie with agents like Allard and Mancini for the purpose of getting a share of the Buenos Aires art market was not unique. By 1907, the Georges Bernheim Gallery had started to regularly send from Paris groups of European paintings to be shown at the Witcomb Gallery. These exhibitions would continue until the mid-1920s. Held in tandem with the exhibitions of Allard during the months of May and June, they provoked the press to compare the quality and results of both. Georges Petit (1856–1920) and L’Eclectique society[38] also allied themselves with local affiliates for the organization of commercial exhibitions.

Two Major Art Collections in Buenos Aires

José Prudencio Guerrico (assisted by several members of his family) and Lorenzo Pellerano were two leading Argentinian collectors who bought the most from Boussod, Valadon & Cie. They are also examples of the beginning and the end of a trend among local purchasers: the predilection for European nineteenth-century art.

José Prudencio de Guerrico (1837–1902) and his wife bought a total of twenty-three works from Boussod, Valadon & Cie between the 1880s and the first years of the twentieth century. He was part of a family that descended from Spanish immigrants of colonial times and owned big tracts of land in the province of Buenos Aires. His father, Manuel José de Guerrico (1800–76), also a collector, had been responsible for introducing the first European paintings into Argentina in the 1840s. His collecting was continued by his son, José Prudencio, who gave the collection a public profile by installing it in the “house museum” that the family owned on Corrientes Avenue. His widow María Güiraldes de Guerrico (1855–1931) continued expanding the collection after her husband’s death, taking advantage of the art market that by then had developed in Buenos Aires. Manuel Güiraldes (1857–1941), José Prudencio’s nephew, acted both as collector and dealer. In the 1880’s he bought works by Charles Chaplin (1825–91; fig. 9), Julien Dupré (1851–1910), Charles Émile Jacque (1813–94), Frederick Kaemmerer (1839–1902), and Félix Ziem (1821–1911), primarily in the Opera branch of Boussod, Valadon & Cie. Some of these works were probably purchased with the goal of contributing to his uncle’s collection,[39] and others to be offered for sale in the porteño art market.

The Guerrico collection was conceived with the idea that it should serve as the basis for the formation of a national gallery. In 1866, the family patriarch wrote that his European purchases were acquired “with the object of bringing to my country samples of the various European schools that would serve as models for the youth that would like to dedicate themselves to the cultivation of this branch of the fine arts.”[40] The Guerricos made partial donations on the occasion of the Museum’s opening in 1896, but it was not until the 1930s that most of the collection passed into the public domain through the donation, by the daughters and grand-daughters of both collectors, of more than six hundred items including paintings, sculptures, miniatures, porcelains, boxes, fans, ivories, crystals, wood carvings, silverwork, and peinetones.[41]

Toward the end of the 1880s, José Prudencio bought fifteen works at Boussod, Valadon & Cie in Paris, among them marines by Eugène Isabey (1803–86; fig. 10) and Ziem, landscapes by Gustave Courbet (1819–77; fig. 11) and Henri Harpignies (1819–1916), and animal paintings by Charles Émile Jacque and Emile Van Marcke de Lummen (1827–90). These purchases fit in well with the existing collection, which was rich in nineteenth-century French landscapes, genre scenes, and animal paintings, as well as a small number of nudes. Among the latter was Jules Lefebvre’s (1836–1912) Diana surprise, the most expensive picture José Prudencio de Guerrico bought from Boussod, Valadon & Cie (fig. 12). With its life-size nudes, the large Lefebvre canvas, exhibited at the 1879 Paris Salon, was an artistic tour de force. The picture was displayed again in the Universal Exhibition of 1889, and it was perhaps there that Guerrico saw it and decided to pay for it the huge sum of 27,500 francs, surpassing by four or five times the sums paid the same year for smaller pictures by Courbet, Jean Jacques Henner, and Antoine Vollon.[42] The Diana became the centerpiece of the collection. It was hung in a prominent place in the reception room (fig. 4) and “presided” over the meetings and salons that took place there. The mythological subject of the painting and the academic character of the nudes rendered the painting acceptable to bourgeois society, which had strict standards of artistic propriety. Indeed, that same year, José Prudencio and his wife had visited the Paris workshop of Argentinian painter Eduardo Schiaffino (1858–1935),[43] who registered the embarrassment of María Güiraldes de Guerrico in front of a picture of a “full size nude woman,” probably his Reposo (fig. 13). The realistic rendering of a female nude, even though seen from the back, apparently was still shocking to Argentinian viewers who excused the nude in the context of mythology or allegory but were less tolerant when it came to more realistic representations of nude models.[44]

The artists whose works were found in the Guerrico’s collection continued to be featured among the artworks promoted by Boussod, Valadon & Cie in its shipments to Buenos Aires at the beginning of the new century. Thus, at a time of artistic innovation in Europe, when Impressionism and Post-Impressionism gradually came to set the tone in European collections, academic, Realist, and Barbizon School paintings continued to appear on the art market of this faraway southern capital. This is clearly reflected in the collection of Lorenzo Pellerano (18?–1931). A Buenos Aires businessman and banker of Genovese origin, Pellerano started to collect toward the end of century, both during his European travels and by profiting from the multiple possibilities offered by the Buenos Aires art market at the beginning of the twentieth century. Famous for the several purchases he could make in a single exhibition, dealers kept his taste in mind when importing foreign pictures. As critic José León Pagano said: “The stimulus of Pellerano is enough to arrange foreign exhibitions of great interest. His purchases in those circumstances alone justified the trip and made it profitable for the ‘marchand’, now converted into a collaborator of a work defined by its own beauty.”[45] His collection reached 1,200 paintings, including a significant number of old master paintings by such artists as Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck. But the bulk of it comprised nineteenth-century paintings by English, French, Italian, and Spanish artists. His Italian background accounted for his strong preference for Italian art, which alone amounted to about five hundred pieces. The quantity of artworks, which were crammed in every room of his house on Talcahuano Street (fig. 14), led the press to introduce him as “the most important of all South American collectors.”[46] The collection, like many others, held a semi-public status, being accessible to local people and foreigners who visited the city. Works in his collection were also reproduced in the pages of illustrated magazines (fig. 15) and were exhibited for charitable purposes, as occurred in May 1918 for a fundraiser benefiting the British Red Cross.[47]

Through Allard and other agents, Pellerano purchased at least twenty-eight works from Boussod, Valadon & Cie, paying the highest prices for La moisson dans la falaise by Jules Veyrassat (1828–93) and Le grand pardon by Pascal-Adolphe-Jean Dagnan-Bouveret (1852–1929; fig. 16). His collection did not end up in a public institution. A portion of it was sold at auction in 1918, while the remaining part was auctioned off in 1934 and 1938 after the collector’s death in 1931.[48]

The decade of the 1930s was marked by the world financial crisis and, in Argentina, by the coup d’état of September 1930. This signified the end of the sumptuous lifestyle of the turn-of-the-century elite. The end of this consumer cycle, with the dissolution of some collections and the passing of others into the public domain, represents a sort of closure for this first generation of collectors of European art, of which we have discussed only two key examples.

The French State and the Buenos Aires Art Market

Several European nations were interested in the economic advantages offered by the purchasing power of the Buenos Aires public when it came to art. They designed strategies to send contingents of artworks to the city on a regular basis and sought to avoid customs taxes charged by the Argentinian government in order to obtain the greatest return for these commercial operations.

Documentation about the French shipment to the Buenos Aires Centennial Exhibition of 1910, found in the National Archives of France, presents telling evidence about the French state’s interest in inserting itself commercially into the Argentinian art market.[49] A report made by the merchant Josse Bernheim Jeune (1870–1941), who served as conseiller du commerce extérieur de la France, registered the flow of European paintings exported between 1890 and 1907 and the potential profits of this market, which, in his opinion, had not yet been realized:

Evidently, these purchases are insignificant when compared to [the size of] the Argentinian population and the fortunes held by many Argentinians; considering their taste, considering the number of European families that would desire artworks by their compatriots. . . . The annual export of artistic paintings to Argentina should be proportionally the same as those sent to the United States, that is to say a million and a half francs, for its six million inhabitants, while we see only around 40.000 francs at most.[50]

In response to Bernheim’s report, the Comité Permanent des Expositions Françaises des Beaux-Arts à l’Étranger was created in 1907 under the presidency of the academic painter Léon Bonnat (1833–1922) together with the artists and agents Guillaume Dubufe (1853–1909) and Albert Dawant (1852–1923).[51] As the correspondence between the French officials revealed, one of the main goals of the committee was the creation or expansion of audiences for French art abroad. Argentina, due to its economic growth, was considered the only South American country worthy of investing an effort.[52] The purchasing power of the porteño public was indeed highly valued, when we consider that the other country on which the committee focused during its first year was the United Kingdom.[53]

Three shows were held in Buenos Aires, in 1908, 1909, and 1912, and in all of these we can see the cooperation of the dealers and private art galleries already mentioned. Indeed, it is important to realize that, particularly in regard to the export of French art into Argentina, there was a close cooperation between merchants and state[54] as government agencies saw it as their mission to “conquer this country with the superiority of French Art.”[55]

Dubufe and Dawant were charged with the selection of artworks for the first two exhibitions, of 1908 and 1909. Dubufe, who had experience as general organizer of the Salon of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, was appointed general curator, but, as he died on board a Buenos Aires-bound ship in May of 1909, Dawant was in charge of organizing the second exhibition. The third show, in 1912, was under the control of painter Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scevola (1871–1950) and the aforementioned Jean Mancini.

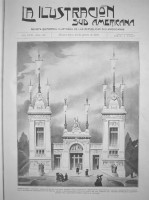

The exhibition of 1908 contained 180 paintings and sculptures by contemporary artists, some of them already known to the Argentinian public, such as Bonnat, Henri Gervex (1852–1929), and Alfred Roll (1846–1919). There was also a “retrospective section” of 110 paintings (done in previous decades) sent by Boussod, Valadon & Cie and selected by Florent Willems (1823–1905) and Mancini.[56] The exhibition opened in Buenos Aires in August in the Pabellón Argentino, an iron and glass building created for showing the Argentinian Section in the Universal Exposition of Paris in 1889 (figs. 17 and 18). It was shipped back to Argentina and re-assembled in the Plaza San Martín in Buenos Aires to house spectacles and exhibitions. The space had been given to the French officials without charge, thanks to the intervention of Eugène Thiébaut, Plenipotentiary Minister of the French Republic in Buenos Aires.[57] Also, the Argentinian ambassador in France acted as advisor, arguing that the “incipient” national art movement would be stimulated by the French exhibition.[58] Dubufe traveled to the country with the objective of monitoring the exhibition, and he gave a series of lectures on French Art to demonstrate that his was not only a commercial enterprise but also an educational crusade.

The result was a commercial success that surpassed the organizers’ expectations. In four weeks, half of the pieces were sold for a total of 325,000 francs. The major profit (53 per cent of the 325,000 francs) was for Boussod, Valadon & Cie,[59] probably due to the fame of artists like William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905), Chaplin, Harpignies, and Jean-François Raffaëlli (1825–1905), who were already favored among the local public. Thanks to the registers of this gallery, it is possible to know the names of the buyers and the values of their transactions.[60] For example, Inés Ortiz Basualdo purchased an important canvas by Bouguereau, Les premiers bijoux (fig. 19), for a very high price—26,000 francs, which represented almost 10 per cent of the total sales of the exhibition. Through the president of the Comisión Nacional de Bellas Artes, José Semprún, MNBA bought La révérence of Adolphe Monticelli (1824–86) for 2,500 francs.[61] In correspondence to his family, Dubufe rejoiced in having sold his landscapes from Capri 60 per cent higher than he would have in Paris.[62]

In spite of the success, Minister Thiébaut warned the French authorities that the Argentinian public should not be underestimated and recommended a better selection for the next exhibition:

It is a mistake to believe that one can send here, consequence-free, the studio’s leftovers. There are many rich Argentinians who are able to satisfy their desire for a picture; all of them have been in Paris and visited our exhibitions; if they are not always enlightened connoisseurs, at least they know the name of fashionable artists and will not allow us to send them what European amateurs did not want.[63]

The second exhibition, held in the same Pavilion in June 1909, comprised a selection of 262 contemporary artworks—primarily paintings but also sculptures and engravings—and shared many features with the previous one.[64] Although the exhibition featured works by some of the same artists represented in 1908, it also showed works by Impressionists Jean Louis Forain (1852–1931), Claude Monet (1840–1926), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), and some of their followers, like André Devambez (1867–1944); Naturalist painters Jules Adler (1865–1952) and Léon Lhermitte (1844–1925); and Symbolists Edmond Aman-Jean (1858–1936), Pierre Carrier-Belleuse (1851–1932), and Edgar Maxence (1871–1954). Boussod, Valadon & Cie and Mancini were once again in charge of the retrospective section, which comprised a total of fifty-eight pictures of landscape, genre, and nudes, including works by Camille Corot (1796–1875), Victor Dupré (1816–79), Henri Fantin-Latour (1836–1904), and Harpignies. These constituted the trademark pieces of the gallery and were favorites of the Buenos Aires inhabitants.[65]

However, this second exhibition did not achieve the same success as the first one. Sales reached only 10,000 francs. As the documents suggest,[66] transportation, lighting, and publicity costs were bigger, but, more significantly, the news about the financial profits of the first show, announced by Dubufe in the Paris Le Figaro,[67] must have inspired private dealers Allard and Bernheim to open their own exhibition in April, before the official salon, making sales of about 300,000 francs. The Buenos Aires market was not big enough to absorb all the art stock sent from France. Besides that, the local public was becoming more selective and began to reject low quality artworks and exaggerated prices.[68] That is to say, the selection committee did not put into practice Thiébaut’s advice from the previous year. In fact, Schiaffino, now director of the National Museum of Fine Arts, highlighted the abundance of “insignificant works” and the lack of “notable ones,” and concluded with irony: “It’s customary to make wine travel in order to strengthen it, but trips have no beneficial effects on paintings.”[69]

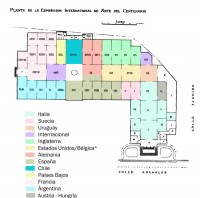

The compensation for the lackluster show of 1909 would come with the Centennial International Exhibition, a large-scale show that reunited the production of several European and Latin-American nations, including Argentina, Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Chile, England, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, United States, and Uruguay (figs. 20 and 21), and took place between July and November 1910.[70] The French section was the biggest, with nearly 400 works that, in the main, followed the pattern established by the previous exhibitions. France wagered on contemporary art with a group in which fin-de-siècle Symbolist works dominated. There were Impressionist paintings by artists such as Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927), Monet, and Renoir, and a small number of academic paintings by artists like Jules Flandrin (1871–1947), Jean-Paul Laurens (1838–1921), and Jules Lefebvre. A considerable number of paintings showed bourgeois genre scenes in several of the different styles of the late nineteenth century: Naturalism, Impressionism, and Symbolism, by such artists as Aman-Jean, Albert Besnard (1849–1934), Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947), Paul Chabas (1869–1937), Maurice Denis (1870–1943), Gaston Hochard (ca. 1863–1913), Gaston Latouche (1854–1913), Henri Le Sidaner (1862–1939), Odilon Redon (1840–1916), Roll, and Edouard Vuillard (1868–1940). Although they did not practice the exact same esthetics, they constituted a line-up that was to be found in the major forums for contemporary art, like the Paris Salons and the Venice International Art Exhibition, as well as in the pages of moderate magazines like L’art et les artistes and L’art decoratif. The presence of sculpture was also significant, including works by Antoine Bourdelle (1861–1929), Jules Desbois (1851–1935), and Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). France was not satisfied with sending only paintings and sculptures by contemporary artists. It also displayed rooms of decorative arts, which caught the attention of local amateurs and were a great success in terms of sales. Thus, the French section realized a net profit of 237,000 francs for the artists, more than three times the initial investment.[71]

Among the thirteen participating nations, France gained one-fifth of the total sales. Most purchases were made by private buyers, but fifteen went to the MNBA,[72] which bought more works from France than from all other nations. Among the acquisitions were The Manicure (La Manicure) by Henry Caro-Delvaille (1876–1928; fig. 22), View of Point-en-Royans (Vue de Pont-en-Royans) by Charles Cottet (1863–1925), The Washerwomen (Les Lavandières) by Etienne Dinet (1861–1929), Ode to Beauty (Chant à la beauté) by Clémentine Dufau (1869–1937; fig. 23), Christian (Chrétien) by Guirand de Scévola, Bust of Falguière by Rodin (fig. 24), and La Berge de la Seine à Argenteuil by Monet (fig. 25).

The final exhibition that closed this series in Buenos Aires was that of 1912. The committee had changed. Even if Bonnat was still officially the president of the Comité Permanent des Exposition Françaises des Beaux-Arts à l’Étranger, the individual responsible for the art selection was now Guirand de Scévola, who had come to Argentina in 1909 and had successfully painted portraits of the local elite as well as participated in the Centennial Exhibition.

The number of works shipped, 161 paintings, was smaller than previously.[73] The cohort of artists had slightly changed, even though most could still be classified as Impressionists, Naturalists, or Symbolists. The artists most prominently represented in the show were Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861–1942), Paul Chabas, Henri Le Sidaner, Lucien Simon (1861–1945), Raffaëlli, Monet, and Renoir. The results of this exhibition were different, perhaps due to the proliferation of commercial expositions in the city. On this occasion, the Argentinian Commission of Fine Arts decided to turn down the retrospective section, and it also refused the reductions and exceptions in customs duties that had been given in the previous years. The National Museum of Fine Arts had now moved to the Argentinian Pavilion, and it was suspected by local artists to house exhibitions organized by dealers instead of works by living artists who wished to make their production known.[74]

As the art market grew, native artists became interested in cornering at least a part of it.[75] This did not, however, result in collectors’ favor toward local paintings. The art produced by Argentinians was known and stimulated by amateurs but was not considered something worthy of collecting. Local collectors clearly privileged foreign production both for decorating their houses and for building their collections. The market’s preference for European art produced an impact on the local art scene that would only start to change in the third decade of the twentieth century.

Epilogue

While these foreign exhibitions were taking place, local artists made themselves heard through the pages of the main artistic journal, Athinae. They questioned the use of a public site for the organization of commercial exhibitions that charged for entry.[76] They also warned against customs exceptions for artworks that obviously were not intended for “artistic education.”[77] Argentinian painters and sculptors also criticized the reluctance of local collectors to buy works by local artists, even if offered at much lower prices than foreign art:

Every painter or sculptor favored by any of our collectors must feel proud of his victory, even if the price paid for his work is not too high. He has overcome the existing prejudice that the only things of value are the imported ones, that there is no Argentinian art, that every creation of local artists not only has no value, but can never have value.[78]

These words may function as a possible epilogue for the process I have described. At the same time when the large exhibitions of foreign art described in the previous section were taking place, the Academy of Fine Arts was nationalized (1905) and the National Salon of Fine Art was established (1911) and thereafter held every September to allow Argentinian artists and foreign artists living in Buenos Aires to show and sell their artworks to the state (for placement in the MNBA) and to the general public. All of this positioned the art made by Argentinians in an unprecedented situation of availability. In the nineteenth century, local production existed, but it was small and its spaces of circulation were restricted to a limited group of connoisseurs and amateurs. European art, and especially nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century French art, continued to fill the porteño galleries during the first decades of the twentieth century, but these works were no longer considered as contemporary or modern, as they once were when Buenos Aires still proudly held the title of the “Paris of South America.”

I would like to thank Caroline “Olivia” Wolf for helping me with the difficult task of writing in English.

All translations are by the author together with Caroline “Olivia” Wolf.

[1] “Las obras de arte, muchas de ellas tituladas tales sin serlo, afluían á millares, especialmente los cuadros, en tal manera, que llegó el momento, hace de esto tres meses, en el que habían por cálculo muy aproximado, una obra de arte, por la que bastante se pedía por cada cuarenta habitantes del municipio, contándose en esta proporción niños lactantes y pobres de solemnidad. En seguida podían venir las obras de arte de menos precio, con lo que habría un cuadro ó una estatua que alcanzaría hasta para los gatos, una vez agotadas las personas en el cálculo, y no es esto exagerado si se tiene en cuenta que exposición hemos tenido y aún tenemos, que ella sola pasa de mil doscientos objetos, de los que ochocientos son cuadros.” “Crónica de arte,” La Nación, October 28, 1888, 1, c. 3–4. All citations to La Nación are to the Buenos Aires newspaper.

[2] Francisco Latzina, comp., Censo General de población, edificación, comercio e industrias (Buenos Aires: Compañía Sud-Americana de Billetes de Banco, 1889), 5:2.

[3] Between 1880 and 1883, he was president of the Municipal Commission of the City of Buenos Aires, and its first Mayor between 1883 and 1887.

[4] Adrián Gorelik, La grilla y el parque. Espacio público y cultura urbana en Buenos Aires 1887–1936 (Buenos Aires: Universidad Nacional de Quilmes, 1998); Federico Ortiz and others, La arquitectura del liberalismo en la Argentina (Buenos Aires: Sudamericana, 1968); and Jorge Francisco Liernur, Arquitectura en la Argentina del Siglo XX: La construcción de la modernidad (Buenos Aires: Fondo Nacional de las Artes, 2001), chap. 1.

[5] Leandro Losada, La alta sociedad en la Buenos Aires de la Belle Époque: Sociabilidad, estilos de vida e identidades (Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, 2008).

[6] Artists like the Italians Nazareno Orlandi (1861–1952) and Franceso Parisi (1857–1948), the Spanish Eliseo Meifrén y Roig (1859–1940) and Julio Vila y Prades (1873–1930), and the French Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola settled in the city in order to favor artistic commissions. Some of them even formed organized groups; for example, Italians gathered around the Associazione Artistica with the aim of exhibiting together. Agents like the Spanish José Artal y Mayoral (1862–1918) and the Italian Ferruccio Stefani also came to Buenos Aires with the purpose of stimulating the introduction and commerce of foreign art. See my book, based on my Phd dissertation, María Isabel Baldasarre, Los dueños del arte: Coleccionismo y consumo cultural en Buenos Aires (Buenos Aires: Edhasa, 2006).

[7] According to the nineteenth-century press, “On donna en général en France le nom de Rastaquouère aux étrangers de mauvais aloi.” “Echos,” La Lanterne (Paris), October 3, 1892, 2, c. 3. The most famous of these literary characters—Iñigo Rastacuero, marquis of the Salteries—creation of writer and journalist Aurélien Sholl, had his postal addresses in Buenos Aires and Valparaíso. See Aurélien Scholl, “Chronique Parisienne. Rastacouères,” Le Figaro, April 19, 1887, 1, c. 1–3. For the history of the use of this literary topos, see Robert Kemp, “Au jour le jour: Exotiques,” L’Aurore (Paris), October 31, 1909, 1, c. 3. See also Rubén Darío, “La evolución del rastacuerismo,” La Nación. Suplemento Semanal Ilustrado, December 11, 1902, 12.

[8] Porteño/a (from “port”) is the adjective used for people or things native to Buenos Aires.

[9] The May Revolution of 1810 initiated the movement toward the break with the Spanish Crown. In that year, Buenos Aires founded its first patriotic government, the Primera Junta, replacing the viceroy, but it was not until 1816—after many intervening battles between the royalists and the patriots—that Argentinian independence was declared.

[10] Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Recuerdos de provincia (Buenos Aires: Salvat, 1970), 103–10; and Lucio V. Mansilla, Entre-nos: Causeries del jueves (Buenos Aires: Casa Editora Juan A. Alsina, 1899), 1:37–38.

[11] In 1905, the Argentinian state took over the private academy organized by the first artists’ association, the Sociedad Estímulo de Bellas Artes.

[12] Laura Malosetti Costa, Los primeros modernos: Arte y sociedad en Buenos Aires a fines del siglo XIX (Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2001), chap. 3.

[13] San Carlos Academy was founded in 1784 by Carlos III, who provided it with bylaws, professors, engraving collections, books, and plaster casts. It officially opened in 1785 with the viceroy presiding over the ceremony. See Flora Elena Sánchez Arreola, “Estudio introductorio,” in Catálogo del Archivo de la Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes, ed. Flora Elena Sánchez Arreola (México: UNAM-IIE, 1996).

[14] Eduardo Báez Macías, Historia de la Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (Antigua Academia de San Carlos) 1781–1910 (México: UNAM, 2009). There was a time when these exhibitions lost their expected periodicity, but they continued to exist—even with discontinuity—throughout the nineteenth century. See also Ray Hernández Duran, “Modern Museum Practice in Nineteenth-Century Mexico: The Academy of San Carlos and la antigua escuela Mexicana,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 9, no. 1 (Spring 2010), accessed November 13, 2015, http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring10/modern-museum-practice-in-nineteenth-century-mexico.

[15] Leticia Squeff, “1879: O Clímax das artes no Rio de Janeiro do Império?” in Uma galería para o Império: A Coleçao Escola Brasileira e as Origens do Museu Nacional de Belas Artes (São Paulo: Edusp-Fapesp, 2012).

[16] Josefina de la Maza, De obras maestras y mamarrachos: Notas para una historia del arte del siglo diecinueve chileno (Santiago de Chile: Metales Pesados, 2014), 99.

[17] “El gobierno no se ha fijado aún de una manera seria en este gran movimiento artístico que se desarrolla y que ya pide ayuda de academia ó museo,” “Crónica de Artes,” La Nación, August 12, 1888, 1, c. 3.

[18] “Es indudable que en estos últimos diez años el gusto por el arte se ha desarrollado extraordinariamente entre nosotros. Ya sea los viajes al viejo mundo, que tan de moda estuvieron durante ese tiempo; ya la introducción al país de algunas obras de importancia, aunque pocas; ya, en fin, el fenómeno natural que tenía que efectuarse durante esta última época de opulencia y que no podía ser menos que favorable para el arte: ciertamente por alguna de esas razones principales contamos hoy en Buenos Aires con un cierto número de galerías artísticas que no tienen nada que envidiar á las colecciones particulares formadas en Europa con obras de artistas modernos. En cantidad tal vez los nuestros sean inferiores; en calidad y valor de las firmas que ostentan sus cuadros, están ciertamente á la altura de aquellos.” Fusain [pseud.], “El Arte en Buenos Aires-Pequeños Museos,” La Prensa (Buenos Aires), June 13, 1892, 4, c. 3.

[19] Roberto Amigo, “El breve resplandor de la cultura del bazar” in Segundas Jornadas. Estudios e investigaciones en artes visuales y música (Buenos Aires: Instituto de Teoría e Historia del Arte Julio E. Payró-FFyL, UBA, 1998), 139–48.

[20] Rubén Darío, “Los falsificadores del arte–A propósito de la tiara de Saitafernes,” La Nación, May 10, 1903, 5, c. 1–2.

[21] Francis Haskell, “Un mártir del atribucionismo: Morris Moore y el Apolo y Marsias del Louvre” in Pasado y presente en el arte y en el gusto (Madrid: Alianza, 1989), 222–46; and Carlo Ginzburg, “Indicios: Raíces de un paradigma de inferencias indiciales” in Mitos, emblemas, indicios. Morfología e historia (Barcelona: Gedisa, 1999), 138–75.

[22] “Crónica de Artes,” La Nación, August 12, 1888, 1, c. 3.

[23] For an index of exhibitions, see Marcelo Pacheco, dir., Archivo Witcomb 1896–1971: Memorias de una galería de arte (Buenos Aires: Fondo Nacional de las Artes / Fundación Espigas, 2000), 239–71.

[24] Fernanda Pitta analyzes the exhibitions organized in Brazil by Pinelo, stating that they were occasions for private purchases and government initiatives. Fernanda Pitta, “A paisagem naturalista estrangeira na coleçao do Museu Mariano Procópio, suas relações com a coleção da Pinacoteca e como o meio artístico brasileiro” in Coleçoes em Diálogo: Museu Mariano Procópio e Pinacoteca de São Paulo, ed. Maraliz de Castro Vieira Christo, exh. cat. (São Paulo: Pinacoteca, 2014), 106–9.

[25] These middlemen, traders who were less professionalized than dealers, and who were sometimes also public officials, bought from producers and sold to retailers or consumers.

[26] Losada, La alta sociedad en la Buenos Aires, 151–66.

[27] Many did this through Bullrich auction house. Baldasarre, Los dueños del arte, chap. 1.

[28] “La fé que nuestro porvenir financiero inspira en el exterior.” “Worth en Buenos Aires. Su futura instalación,” La Nación, April 9, 1893, 3, c. 1. Apparently, this branch was never established in Buenos Aires.

[29] Goupil & Cie was founded in 1827 by Adolphe Goupil (1806–93). In 1861, Léon Boussod (1826–96), who had been associated with Adolphe since 1856, came into partnership with him. René Valadon (1848–1921) married Boussod’s daughter in 1875 and became an associate of the firm of Goupil in 1878. In 1884, the Goupil family retired, and the firm was renamed Boussod, Valadon & Cie, successeurs de Goupil & Cie. “Goupil (Biographical Details),” The British Museum, accessed January 24, 2017, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=123112. For a useful introduction to the books of Goupil & Cie belonging to the archives of the Getty Research Institute since 1989, see Agnès Penot, “The Goupil & Cie Stock Books: A Lesson on Gaining Prosperity through Networking,” Getty Research Journal, no. 2 (2010): 177–82; and Christian Huemer & Agnès Penot, “Un’eccezionale prova documentaria: Gli archivi Goupil al Getty Research Institute” in La Maison Goupil: Il successo italiano a Parigi negli anni dell’Impressionismo, ed. Paolo Serafini, exh. cat. (Rovigo: Palazzo Roverella, 2013), 69–75. I’m grateful to Agnès Penot for suggesting these articles to me.

[30] The research was carried out in the online database, “Dealer Stock Books,” Getty Research Institute, last accessed July 15 2015, http://piprod.getty.edu/starweb/stockbooks/servlet.starweb?path=stockbooks/stockbooks.web.

[31] Emilio Furt purchased five works between 1911 and 1913, two of them by Émile-René Menard in the solo exhibition organized by Allard in Buenos Aires in 1913. César Cobo Ocampo bought four pictures between 1911 and 1913, also with Allard as middleman. Many of these artworks entered the MNBA thanks to the donation of the collectors or Furt’s descendants in 1920 and Cobo’s in 1939. Francisco Llobet was one of the leading clients and promoters of Impressionist painting in Buenos Aires. He bought four works—in 1911 and 1912—and in three of them Allard appeared as middleman. Emilio Lernoux purchased a total of twelve works between 1908 and 1913, almost all of them with Allard and Mancini as agents, the most expensive being Maternité by Eugène Carrière for which he paid 37,000 francs. The Santamarina family, one of the most powerful landowner families of Argentina, included various collectors like Enrique (1870–1937) and Antonio (1880–1974). This last formed the most exquisite group of Impressionist painting in the country. The different family members made seven acquisitions between 1909 and 1913, also with the aforementioned agents as intermediaries, the most expensive being La sieste en moisson by Léon-Augustin Lhermitte bought by Enrique Santamarina in 1913.

[32] For a study of the first art collecting in Argentina, see Baldasarre, Los dueños del arte.

[33] In Fundación Espigas Library (Buenos Aires) there are catalogues of the exhibitions, in association with Boussod, Valadon & Cie, of 1911 (Galerie française: IVme exposition), 1912 (Galerie française: Vme exposition), and 1913 (Galerie française: VIme exposition). By press records, we know that a collective exhibition of French Art was held in May 1910, and two exhibitions of the Societé des Aquarellistes Françaises were held in June 1911 and 1912. Allard had already organized two exhibitions in Buenos Aires in 1907 (Exposition d’une collection de tableaux modernes français et étrangers) and 1909 (Exposition d´une Collection de Tableaux de maîtres modernes français et étrangers).

[34] “Movimiento artístico del mes,” Athinae 2, no. 10 (June 1909): 27. This source referred to sales in francs. The amount was equivalent to 95,000 pesos.

[35] In 1908 and 1909, in alliance with Boussod, Valadon & Cie, he was in charge of the retrospective section of the exhibition of French art organized by the Comité Permanent des Expositions des Beaux-Arts à l’Étranger.

[36] “C’est dont avec joie que j’ai vu Mancini s’enrôler parmi les pionniers hardis qui vont prêcher, en Argentine, la Beauté ainsi que la conçoit l’École française” J. Mancini, Expert d’art, Exposition d’Œuvres importantes d’Artistes Français à Buenos-Ayres (np: 1910). According to press records, Mancini organized his exhibition of 1908 with works belonging to Boussod, Valadon & Cie. See “El año artístico,” Athinae 2, no. 5 (January 1909): 27–29.

[37] L. Roger-Milès, “Préface” to Exposition d’art français à Buenos-Aires, by Galeries Georges Petit et J. Mancini, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: Galeries Georges Petit et J. Mancini, 1913).

[38] The “Société l’Eclectique” was founded in 1908 by painter and writer Pierre Calmettes in cooperation with Anatole France, Léonce Bénédite, Claude-Roger Marx, Armand Dayot, and Camille Mauclair. It organized exhibitions at the Chaine et Simonson Gallery at 19, rue Caumartin, Paris. “Expositions,” Art et Décoration: Revue mensuelle d’art moderne, Supplément, December 1908, 10.

[39] We presume that two of the works bought by Güiraldes in 1887 and 1888 went to Guerrico’s collection and, from there, ended in the collection of MNBA. They are Charles Émile Jacque, Coq et poules, 26 x 40.5 cm (En el gallinero, inv. 2736, MNBA), and Charles Chaplin, Dans les rèves, 64.5 x 42.5 cm (Rêverie, inv. 2759, MNBA).

[40] “con el objeto de traer a mi país muestras de las diversas escuelas de Europa que sirviesen de modelo a la juventud que quisiese dedicarse al cultivo de este ramo de las bellas artes,” Manuel José de Guerrico to Don Manuel Ricardo Trelles, May 1, 1866, quoted in Crítica (Buenos Aires), March 18, 1938 and in La Nación, June 5, 1938.

[41] Rio de la Plata’s version of the Spanish “peineta” (decorative comb) but larger and made of turtle shell.

[42] As a reference, by that date a square meter of land in the Notre-Dame neighborhood cost 622 francs.

[43] Between 1895 and 1910, Eduardo Schiaffino was the first Director of National Museum of Fine Arts (MNBA).

[44] See letter of Eduardo Schiaffino to his mother, París, January 4, 1889, file 9-3333, Archivo Schiaffino, Archivo General de la Nación, Buenos Aires.

[45] “El estímulo de Pellerano basta para determinar exposiciones extranjeras de mayor interés. Lo adquirido por él en tales circunstancias, sólo eso, justificaba el viaje y lo hacía provechoso, para el ‘marchand’, convertido así en colaborador de una obra definida por su propia belleza,” José León Pagano, introduction to “La colección Pellerano,” La Galería de cuadros de Don Lorenzo Pellerano (Buenos Aires: Guerrico & Williams, 1933).

[46] Emilio Dupuy de Lôme, “La galería de cuadros de Don Lorenzo Pellerano,” Plus Ultra 2, no. 9 (January 1917), unpaginated.

[47] “En la galería Pellerano, Fiesta de la Cruz Roja Británica,” La Nación May 14, 1918, 8–9.

[48] Colección Lorenzo Pellerano (Buenos Aires: Naón y Bustillo, 1918); La Colección Pellerano (Buenos Aires: Guerrico & Williams, 1934); and Judicial. 4ª Venta de la Colección Pellerano (Buenos Aires: J. C. Naón & Cia., 1938).

[49] Anne-Sophie Aguilar has noted the importance of artists’ associations in the organization of French exhibitions abroad and how, in a context of strong nationalism, the state engaged in which kind of French Art should be selected for national representation. See Anne-Sophie Aguilar, “Enjeux esthétiques et politiques de la représentation de l’art français à l’étranger au début du XXe siècle: Le cas de la XI. Internationalen Kunstausstellung de Munich, 1913,” in Voir, ne pas voir: Les expositions en question, ed. Marie Gispert and Maureen Murphy (Paris: Journées d’étude, INHA, 2012), 1–21, http://hicsa.univ-paris1.fr/documents/file/Aguilar.pdf.

[50] “Evidemment ces achats sont insignifiants au regard de la population argentine et de la fortune possédée par nombreux d’Argentins; en considération de leur gout, en considération enfin du nombre de familles européennes qui aimeraient les œuvres de leur compatriotes. . . .

Les importations annuelles de peintures artistiques en Argentine devraient représenter au moins la même proportion qu’aux États-Unis, c’est-à-dire un million et demie de francs, pour le six millions d’habitants de la population tandis que l’on voit seulement au plus haut 40.000 francs environ.” Josse Bernheim Jeune, Rapport sur le suppression des droits de douane à l’entrée de Peintures artistiques en Argentine, May 1910, AN-F-21-8822, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[51] Aguilar, “Enjeux esthétiques,” 4–5, mentions the debate that took place in the press after the creation of the committee, mainly regarding its partiality and the absence of certain artists like the members of the Sociétaires du salon d’Automne. This article does not refer to the committee´s action in Argentina.

[52] “En outre nos artistes ne doivent pas perdre de vue que de tous les pays de l’Amérique du Sud, la République Argentine est le seul, en raison de sa situation économique, qui puisse offrir actuellement un débouché de quelque importance à leur productions et c’est en conséquence à conquérir ce marché qu’ils doivent employer tous leurs efforts.” Minister of Foreign Affairs to the Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts, Paris, October 23, 1908, AN-F-21-4070, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[53] In 1908, it organized the so-called Franco-British Exhibition in London.

[54] In her master’s thesis about French exhibitions abroad in the interwar period, Pauline Chougnet states that at the beginning of twentieth century the big Parisian galleries had a monopoly on artistic promotion abroad thanks to the effectiveness of their international resources. Pauline Chougnet, “Les expositions d’art français à l’étranger au tournant du siècle et jusqu’à la Première Guerre mondiale” in Les expositions d’art français organisées par la France à l’étranger pendant l’entre-deux-guerres (Paris: École Pratique des Hautes Etudes, 2009), 8–28.

[55] “conquerir ce pays à la superiorité de l’art français.” Léon Bonnat, G. Dubufe, and A. Dawant to Mr. Vice-Secretary of State, Paris, April 4, 1908, AN-F-21-2736, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[56] Francisco Soto y Calvo, preface to Salón del arte francés organizado por el Comité Permanente de las Exposiciones de Bellas Artes en el Extranjero, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimerie F. Jourdan, 1908).

[57] Thiébaut was also able to arrange for customs duties to be paid not when the works were brought in, but only when the imported works were sold.

[58] “Es también indudable que nuestro incipiente arte nacional recibirá un estímulo eficaz.” Ernesto Bosch, Legation of the Argentine Republic to [Estanislao Zeballos] Minister of Cultural and Foreign Affairs, Paris, February 24, 1908, Section, 1908, Box 1021, Diplomatic and Consular, Archivo del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Culto, (AMREC), Buenos Aires.

[59] M. Thiébaut, Plenipotentiary Minister of the French Republic in Buenos Aires to M. M. Stephen Pichon, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Buenos Aires, September 12, 1908, AN-F-21-4070, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[60] Among other buyers were Pedro Méndez, Alejandro Estrogamou, Victoria Aguirre—one of the main women art collectors of the decades to come—Santiago Luro, and Adán Diehl.

[61] Adolphe Monticelli, La révérence aux hommes d’armes, oil on canvas, 36.5 x 54.5 cm, inv. 6298, MNBA.

[62] Guillaume Dubufe to his wife, Cecile, Buenos Aires, August 20, 1908, MS 407-16-I, Archives de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris.

[63] “Ce serait une erreur de croire qu’on peut envoyer ici impunément des fonds d’atelier. Les argentins assez riches pour se passer la fantaisie d’un tableau sont nombreux; ils ont tous été à Paris et ont fréquenté nos Expositions; s’ils ne sont pas toujours des connaisseurs éclairés, du moins savent-ils les noms des artistes en vogue; ils n’admettront pas qu’on leur envoie ce dont les amateurs d’Europe n’ont pas voulu.” M. Thiébaut, Plenipotentiary Minister of the French Republic in Buenos Aires to M. M. Stephen Pichon, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Buenos Aires, September 12, 1908, AN-F-21-4070, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[64] Catalogue du IIme Salon d’art français organisé par le Comité Permanent des Expositions des Beaux-Arts à l’étranger, Buenos-Aires 1909, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimerie Jourdan, 1909).

[65] Again, the database of Boussod, Valadon & Cie allows us to affirm that at least twenty-three works from the retrospective section were sold to the main city collectors like Pedro and Santiago Luro, Carlos Ocampo, Gastón Fourvel Rigolleau, Lorenzo Pellerano, and Ángel Pacheco Anchorena.

[66] M. Thiébaut, Plenipotentiary Minister of the French Republic in Buenos Aires to M. Stephen Pichon, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Buenos Aires, August 20, 1909, AN-F-21-4070, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[67] “Les peintres français dans l’Argentine,” Le Figaro, October 29, 1909.

[68] “On connait assez bien ici la ‘cote’ de nos peintres, et devant certaines prétentions on hausse les épaules et l’on n’achète pas.” M. Thiébaut, Plenipotenciary Minister of the French Republic in Buenos Aires to M. Stephen Pichon, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Buenos Aires, August 20, 1909, AN-F-21-4070, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[69] “Es comprensible que se haga viajar el vino para entonarlo, pero los viajes carecen de virtud sobre la pintura.” Eduardo Schiaffino, “Impresiones y comentarios, El Salón Francés II,” La Nación, July 17, 1909, 5, c. 2–3.

[70] See Exposición internacional de arte del Centenario: Buenos Aires 1910: Catálogo, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires: M. Rodríguez Giles, 1910).

[71] See M. (Marcel) Horteloup, Le Sous-Commissaire des Expositions des Beaux-Arts, Rapport sur la section des beaux-arts à l’Exposition du Centenaire de la République Argentine à Monsieur Dujardin Beaumetz, Sous-Secrétaire d’Etat des Beaux-Arts, Paris, June 21, 1911, 29-30, AN-F-21-4070, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[72] “Exposición Internacional de Arte: Lista de los importes totales de obras vendidas en las diversas secciones,” Athinae 3, no. 29 (January 1911).

[73] III Salon de l’art français organisé par le comité des Expositions Sud-Américaines, sous le patronage des gouvernements argentin et français, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimerie Georges Petit, 1912).

[74] André Saglio, Commissariat des Expositions des Beaux-Arts en France et à l’Étranger pour le Bureau des Travaux d’art, Musées et Expositions, Grand Palais, September 28, 1912, AN-F-21-2736, Archives Nationales, Paris.

[75] During the 1890s, the Ateneo, a group of artists and intellectuals, organized four collective exhibitions of local artists. These shows had poor sales results. A central book about the formation of the artistic field in Buenos Aires during the late nineteenth century is Costa, Los primeros modernos, chap. 9.

[76] “Segundo salón oficial del arte francés,” Athinae 2, no. 10 (June 1909): 22–23.

[77] “Arte francés en Buenos Aires,” Athinae 2, no. 8 (April 1909): 15–16.

[78] “Todo pintor ó escultor argentino que se vea favorecido por alguno de nuestros coleccionistas, no sea muy elevado el precio pagado por su obra, se debe sentir orgulloso de su victoria. Ha vencido, efectivamente el prejuicio subsistente aún de que no vale sino lo importado, de que no hay arte argentino, de que todo lo que crean los artistas del país no solamente no vale, sino que no puede valer.” “El arte y la ‘boutique’,” Athinae 2, no. 8 (April 1909): 14.