The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Portrait of Emma Darwin by Charles Fairfax Murray

Though the Portrait of Emma Darwin (fig. 1), on loan to Darwin College, University of Cambridge, is not, strictly speaking, a “new discovery,” recent research of this little-known work has uncovered extensive evidence suggesting that it was painted by the artist Charles Fairfax Murray in 1887.[1] The portrait has long been owned by the Darwin Heirloom Trust, which identified it as “nineteenth-century English School”; recently, however, it has been attributed to Walter William Ouless.[2] This article aims at refuting that attribution by showing that the portrait was done by Murray instead.

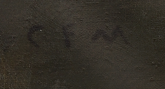

To begin, the initials “CFM,” frequently used by Murray to sign his paintings, are visible on the top-left of the canvas (fig. 2).[3] Additionally, “+ Mrs CHARLES DARWIN + C.F.M. + P +” is written on the verso. Reference to Charles Fairfax Murray’s authorship of a portrait of Emma Darwin has been made twice before in the literature, though in both cases parenthetically.[4]

The idea of a portrait of Emma Darwin was first broached in a letter from John Henry Middleton, Slade Professor of Fine Art in Cambridge, to Murray in December 1886: “You must come to Cambridge next term. The Darwins want you to paint the Old Mrs Darwin.”[5] The idea came to fruition two months later, when George Darwin, son of Charles and Emma, wrote to Murray on February 14, asking him to paint a portrait of his mother.[6] Murray replied the following day, and arrangements were made to begin the portrait.[7]

George and his brother, Horace Darwin, seem to have met Murray through their connections to Middleton and Albert George Dew-Smith. Dew-Smith had studied with Horace Darwin at Trinity College, and they founded the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company together in 1881.[8] Middleton, who had become friends with Dew-Smith during his time in Cambridge and through their common interest in collecting, first met Murray in Florence.[9] When Murray returned to London to take up a studio in Holland Park in 1886, Middleton regularly urged Murray to visit him in Cambridge.[10] It seems to be through Middleton that Murray became friends with Dew-Smith and was introduced to the Darwins. In July 1886, before there is written mention of the portrait of Emma Darwin, Middleton wrote to Murray that “Dew Smith and the Darwins want you again.”[11]

As Slade Professor of Fine Art in Cambridge, Middleton may have influenced George Darwin’s choice of Murray to paint his mother’s portrait. Middleton himself would have been interested in satisfying Murray, not only due to their friendship, but because Murray supplied him with photographs of Florentine art for his lectures at the Royal Academy, photographs which he later donated to the Fitzwilliam Museum.[12] However, probably more crucial to the choice of Murray was his relatively low fee. In his first letter to Murray, George Darwin wrote that “Dew Smith tells me that he believes that your price is £50. . . . I should like to have this point clear as my pocket is by no means of infinite depth.”[13] In comparison, Walter William Ouless, who had painted the Portrait of Charles Darwin (currently also on loan to Darwin College from the Darwin Heirloom Trust) in 1875, was charging £525 in the 1890s for similarly sized portraits.[14]

Murray was eager to commit to the portrait and readily accommodated the needs of an aging Emma Darwin. As well as travelling to Cambridge for the sittings, he supplied all the materials, only requesting an easel to be borrowed from Dew-Smith.[15] In a letter to her son Leonard, Emma Darwin wrote of this conscientiousness: “I am only to give him 2 sittings of 3/4 of an hr [sic] in the day—The difficulty is that no one of established reputation would spend so much time in journies [sic] etc to please the sitter & regular long sittings I could not stand.”[16]

On February 21, Murray visited Emma Darwin’s house, The Grove, Cambridge, to begin the sittings for the portrait; he returned the following week on the 28th.[17] He began with a pastel drawing of Emma Darwin, which was to be used as a preliminary sketch for the oil painting. After the initial sittings in February 1887, Emma Darwin wrote on multiple occasions of the portrait’s positive development, commenting that Murray’s pastel drawing “is said to be very like so far.”[18]

It was not until August 1887 that the final sittings were organized. Emma Darwin spent her summer at Down House in Kent, and plans were made for Murray’s visit on August 10.[19] Murray wrote to George Darwin of the need “to raise your mother in her chair to the same height as at Cambridge,” to which Emma Darwin obliged.[20] Murray had anticipated the possibility of a “definite obstacle at Down,” fearing that the room at Down House might not be as favorable for work as the one in The Grove, which had been “very good.”[21] His fears proved to be grounded, and after visiting Down, Murray complained that the “different shape of the room . . . made it impossible to place her in the same light.” He appears to have made only one visit to Down House.[22]

After returning from a trip to Italy, Murray wrote to George Darwin on October 4, 1887 to schedule a visit to Cambridge to finish the portrait. While in Cambridge, Murray was to stay with John Henry Middleton,[23] and Emma Darwin’s diary records Murray’s visits to The Grove on October 13, 14, and 15, noting that “Mr Murray finished” on October 20, 1887.[24]

The Portrait of Emma Darwin, measuring 35 1/2 in. x 27 in.,[25] was hung in George Darwin’s house, Newnham Grange—now part of Darwin College—by December 2, 1887.[26] The preliminary pastel drawing was purchased by Horace Darwin in November 1887 for £21,[27] and now hangs in Down House as part of the English Heritage collection, correctly attributed to Charles Fairfax Murray (fig. 3).

The Portrait of Emma Darwin is not representative of Charles Fairfax Murray’s most noted Pre-Raphaelite style,[28] though it does bear stylistic similarities to his other portraits, such as his Portrait of William Morris.[29] An important factor in the portrait’s development was a photograph sent to Murray at the outset of the commission. When George Darwin first wrote to Murray in February 1887, he enclosed “an excellent photograph of my mother (which I beg you to return some time) as I think you may like to see your proposed sitter.”[30] Murray used this photograph for “previous study,” and Emma Darwin noted that he intended to use it, alongside the pastel drawing, for finishing the oil portrait.[31] It seems certain that this was a print of a photograph taken by Herbert Rose Barraud in 1881 (fig. 4). Emma Darwin’s pose in the photograph is very similar to that in Murray’s painting. Even more alike are the hands, which seem directly copied from the photograph, which makes sense given that Emma Darwin wrote how she would entertain herself while sitting for Murray by “reading aloud and knitting.”[32]

All this is not to say that Charles Fairfax Murray’s Portrait of Emma Darwin is a copy of the Barraud photograph. While Emma Darwin’s face in Murray’s pastel drawing is similar to the Barraud photograph, her face in the final portrait is quite different. Though Murray painted his portrait six years after Barraud took the photograph, Emma Darwin’s face looks younger in the portrait. Murray’s Portrait of Emma Darwin also differs from the photograph in that the head is closer to the top of the canvas and more of her body is seen at the bottom, a change that lends to the figure a stately, matriarchal allure. George Darwin wrote to Murray that his wife, Maud Darwin, disagreed with the height of Emma Darwin’s position on the canvas and suggested that the portrait “would be improved if 6 inches or so were cut off the bottom.”[33] In his reply, Murray rejected the idea, “as it would reduce [the canvas] to nearly a square form,” which George Darwin accepted, writing of having “quite given up the idea of altering the size.”[34]

Murray did make at least one change to the portrait, however. He had written to George Darwin in response to Maud’s complaint about the height of the figure that “the high cap makes the head appear nearer the top than it really is, but I must also allow a preference for this kind of composition almost universal amongst the old masters.”[35] Yet, Murray did end up altering the cap, writing to George Darwin of having “improved [it] considerably.”[36] The all-white cap in the pastel drawing differs from that of the final portrait, with the latter including a piece of black fabric. The paint used for the black fabric has become transparent over time, revealing, upon close inspection, a layer of white paint underneath. This suggests that the black fabric may have been one of the additions after the painting was initially completed.

In a letter enclosed with the delivery of the portrait, Murray wrote that “the green color of the background & much else has dried in rather dead, and will remain so till [sic] the varnish brings it out again.”[37] The dark tones of the portrait presented an ongoing concern for the Darwins and Murray. Writing on December 17, 1887, George Darwin informed Murray that where the portrait “was first hung the light was very bad & absolutely nothing but blackness was visible in the lower paint.”[38] It was not until April 1889 that Murray varnished the painting and wrote to George Darwin that “it’s more visible for the varnish.”[39] It is possible that Murray had used a copper green pigment, which is known to darken over time and suffer from chemical degradation processes. Varnishing may have saturated the paint and initially restored the original green hue of the background. However, a letter from Middleton to George Darwin, written on July 28, 1887, expresses Murray’s continued sense of failure regarding the portrait.[40]

George Darwin does seem to have generally approved of the portrait, though. Emma Darwin wrote that he was “quite satisfied” and “highly pleased” with it.[41] Remarking on the portrait herself, Emma Darwin wrote that she “looked dignified” and “very respectable,” and the sincerity of this opinion seems to be supported by her unabashed expression of dislike for Ouless’s Portrait of Charles Darwin.[42] In relation, it is also interesting to note George Darwin’s attempt in 1888 to commission Murray to paint a portrait of his wife, Maud, suggesting his high regard for Murray.[43]

Later generations of the Darwin family also thought favorably of Murray’s work, with Ida Darwin, Horace’s daughter, calling the pastel drawing an “excellent portrait of H D’s mother.”[44] But perhaps the most pertinent remarks on the final portrait came from Emma Darwin’s daughter, Henrietta Litchfield, writing in her 1904 publication of her mother’s letters:

Early in 1887 she sat for her portrait to Mr Fairfax Murray. This oil-painting is in the possession of George, for whom it was painted. It is a good picture and the features are extremely like. The expression which it gives was hers at times, but it was not that which to my mind best reveals her nature. It is too grave, and even stern.[45]

For Charles Fairfax Murray, whose only interaction with Emma Darwin came when she was in her late seventies and restlessly sitting for a portrait, her expression might well have been somewhat stern. To her children, who had known her as the lively, intelligent, and energetic woman whose watercolor portrait George Richmond had painted forty-seven years earlier, she may indeed have appeared grave and stern.

Matthew Turner

Cambridge University

mt634[at]cam.ac.uk

I would like to thank Petra Chu for her excellent editing of the original manuscript, as well as Robert Alvin Adler for his copyediting and Isabel Taube for her assistance with the images. Many thanks must also be sent to all at Darwin College, University of Cambridge, but especially Peter Brindle for his enthusiasm and financial support of the research, and John Dix for continuing such support. Lastly, I would like to thank Kristin de Ghetaldi for her technical advice on artists’ materials, and the ever-willing and congenial help of librarians in the Manuscripts Reading Room at Cambridge University Library.

[1] On Charles Fairfax Murray, see David Elliott, Charles Fairfax Murray: The Unknown Pre-Raphaelite (Lewes: Book Guild, 2000); Paul Tucker, “Responsible Outsider: Charles Fairfax Murray and the South Kensington Museum,” Journal of the History of Collections 14, no. 1 (2002); 115–37; and Julie F. Codell, “Charles Fairfax Murray and the Pre-Raphaelite ‘Academy’: Writing and Forging the Artistic Field,” in Collecting the Pre-Raphaelites: The Anglo-American Enchantment, ed. Margaretta Frederick Watson (London: Ashgate, 1997), 35–49.

[2] Janet Browne, “Looking at Darwin: Portraits and the Making of an Icon,” Isis 100, no.3 (2009): 542–70.

[3] See the initials on the recto of Charles Fairfax Murray, Emma Darwin, née Wedgwood, 1887. Pastel on linen-lined brown paper. Down House, English Heritage, Kent; and Charles Fairfax Murray, The King’s Daughters, ca. 1875. Oil on panel. Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.

[4] James D. Loy & Kent M. Loy, Emma Darwin: A Victorian Life (Gainsville: University of Florida Press, 2010), 323; and Frances Spalding, Gwen Raverat: Friends, Family and Affections (London: Harvill Press, 2001), 30.

[5] John Henry Middleton (cited hereafter as Middleton) to Charles Fairfax Murray (cited hereafter as Murray), December 28, 1886, Eng Ms 1281 M (477), Special Collections, John Rylands Library, Manchester (cited hereafter as JRL).

[6] George Darwin to Murray, February 14, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (219), JRL.

[7] Murray to George Darwin, February 15, 1887, DAR 251: 2298, Manuscripts Reading Room, Cambridge University Library, Cambridge (cited hereafter as CUL).

[8] Tim M. Berra, Darwin and His Children: His Other Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 163.

[9] Elliott, Charles Fairfax Murray, 163–64.

[10] Middleton to Murray, July 30, 1886, Eng Ms 1281 M (475), JRL; and Middleton to Murray, December 28, 1886, Eng Ms 1281 M (477), JRL.

[11] Middleton to Murray, July 30, 1886, Eng Ms 1281 M (475), JRL.

[12] Middleton to Murray, December 10, 1886, Eng Ms 1281 M (476), JRL; and Middleton to Murray, February, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 M (479), JRL. Middleton’s contributions to the Fitzwilliam Museum at this time are particularly relevant given that he was attempting to become Director of the museum (see Middleton to Murray, December 28, 1886, Eng Ms 1281 M [477], JRL) for which he was appointed in 1889. Murray also became a consultant and an art dealer for Middleton and the Fitzwilliam Museum. See Middleton to Murray, November 9, 1889, Eng Ms 1281 M (481), JRL. For more on Murray as an art dealer, see Tucker, “Responsible Outsider.”

[13] George Darwin to Murray, February 14, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (219), JRL.

[14] “Notes on Artists” (Ouless, Walter William), “WW Ouless Paintings,” National Portrait Gallery Archive, London.

[15] Murray to George Darwin, February 15, 1887, DAR 251: 2298, CUL.

[16] Emma Darwin to William Darwin, undated, DAR 219: 1: 220, CUL.

[17] Emma Darwin’s Diary, February 21, 1887, DAR 242:51, CUL; and Murray to George Darwin, February 15, 1887, DAR 251: 2298, CUL. On February 28, 1887, Emma Darwin wrote, “Today he carries off the chalk drawing & uses it to copy oils and comes again some time [sic] hence.” Emma Darwin to William Darwin, February 28, 1887, DAR 219: 1: 208, CUL.

[18] Emma Darwin to William Darwin, February 28, 1887, DAR 219: 1: 208, CUL; also see “they all think it very like” in Emma Darwin to Leonard Darwin, March 1, 1887, DAR 239: 23: 5: 14, CUL.

[19] George Darwin to Murray, July 30, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (220), JRL; and Murray to George Darwin, August 2, 1887, DAR 251: 2959, CUL.

[20] Murray to George Darwin, August 5, 1887, DAR 251: 2958, CUL; and Emma Darwin to Murray, August 6, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (218), JRL.

[21] Murray to George Darwin, August, 5 1887, DAR 251: 2958, CUL.

[22] Murray to George Darwin, October 4, 1887, DAR 251: 2954, CUL; and Emma Darwin’s Diary, August 10, 1887, DAR 242:51, CUL.

[23] George Darwin to Murray, October 6, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (221), JRL.

[24] Emma Darwin’s Diary, October 20, 1887, DAR 242:51, CUL.

[25] Murray wrote that his portrait measured “36x28” in. See Murray to George Darwin, December 5, 1887, DAR 251: 2949, CUL; measurements of “35 ½ in. by 27 in.” were taken of the canvas by Christie’s, Manson & Woods Ltd. in December 1995. See “The Property of the Darwin Foundation on Loan to Darwin College, Silver Street, Cambridge,” DC/503/1, Darwin Heirlooms Trust 1995–1998, Darwin College Archive, Cambridge.

[26] George Darwin to Murray, December 2, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (223), JRL. There is no record of which room the portrait was hung in until December 1889, when it was hung in the Drawing Room of Newnham Grange, currently the Reading Room at Darwin College. Emma Darwin mentions that the veranda blocked sunlight from illuminating the portrait, and, as only the Drawing Room at Newnham Grange had a veranda, it necessarily follows that the portrait was hung in the Drawing Room. See Emma Darwin to William Darwin, December 7, 1887, DAR 219: 1: 193, CUL.

[27] Horace Darwin to Murray, November 8, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (230), JRL; and Murray to Horace Darwin, November 9, 1887, DAR 258: 1742, CUL.

[28] See Charles Fairfax Murray, The Violin Player, 1888. Oil on canvas. National Museums, Liverpool; and Charles Fairfax Murray, The King’s Daughters, ca.1875. Oil on panel. Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.

[29] Charles Fairfax Murray, Portrait of William Morris, ca. 1870. Oil on canvas. William Morris Gallery, London.

[30] George Darwin to Murray, February 14, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (219), JRL.

[31] Murray to George Darwin, February 15, 1887, DAR 251: 2298, CUL; and Emma Darwin to Leonard Darwin, March 1, 1887, DAR 239: 23: 5: 14, CUL.

[32] Emma Darwin to Leonard Darwin, 1887, DAR 239: 23: 5: 11, CUL.

[33] George Darwin to Murray, December 2, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (223), JRL.

[34] Murray to George Darwin, December 5, 1887, DAR 251: 2949, CUL; and George Darwin to Murray, December 17, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (222), JRL.

[35] Murray to George Darwin, December 5, 1887, DAR 251: 2949, CUL.

[36] Murray to George Darwin, November 14, 1889, DAR 251: 3547, CUL.

[37] Murray to George Darwin, 1887, DAR 251: 2963, CUL.

[38] George Darwin to Murray, December 17, 1887, Eng Ms 1281 D (222), JRL.

[39] Murray to George Darwin, April 20, 1889, DAR 251: 3357, CUL.

[40] Middleton to George Darwin, July 28, 1889, DAR 251: 3545, CUL.

[41] Emma Darwin to Leonard Darwin, undated, DAR 239: 23: 5: 21, CUL; and Emma Darwin to William Darwin, December 7, 1887, DAR 219: 1: 193, CUL.

[42] Emma Darwin to William Darwin, December 7, 1887, DAR 219: 1: 193, CUL; and Emma Darwin to Leonard Darwin, undated, DAR 239: 23: 5: 21, CUL. For opinions of Ouless’s Portrait of Charles Darwin, see Janet Browne, Charles Darwin, vol. 2: The Power of Place (London: Jonathan Cape, 2002), 424.

[43] This portrait was never finished, and the correspondence between the Darwins and Murray suggests Murray’s evasion of the commission. Indeed, Murray even had to write an apology to Maud Darwin when he did not show up to meet her at the portrait sitting that they had arranged. See George Darwin to Murray, February 10, 1888, Eng Ms 1281 D (224), JRL; Murray to George Darwin, 1888, DAR 251: 1930, CUL; Murray to Maud Darwin, May 12, 1888, DAR 251: 1939, CUL; Murray to George Darwin, June 13, 1888, DAR 251: 1940, CUL; George Darwin to Murray, January 31, 1889, Eng Ms 1281 D (225), JRL; Murray to George Darwin, February 1, 1889, DAR 251: 3365, CUL; Murray to George Darwin, February 28, 1889, DAR 251: 3362, CUL; Murray to George Darwin, April 20, 1889, DAR 251: 3357, CUL; and Albert Dew-Smith to Murray, September 26, 1889, Eng Ms 1281 D (244), JRL.

[44] Ida Darwin’s annotated note of July 1930 in Murray to Horace Darwin, March 17, 1890, DAR 258: 1744, CUL.

[45] Henrietta Litchfield, Emma Darwin: A Century of Family Letters (Cambridge: University Press, 1904), 372.