The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Der Ring: Pionierjahre einer Prachtstrasse / Vienna’s Ringstrasse: The Making of a Grand Boulevard

Wien Museum Karlsplatz, Vienna

June 11–October 4, 2015

Last summer’s extended heat wave in Vienna may have taken some of the pleasure out of a stroll around the Ringstrasse, but inside the just-cool-enough galleries of the city’s museums there were plenty of other opportunities to appreciate the famed boulevard (fig. 1). Several exhibitions, some modest and others more ambitious, all accompanied by substantial scholarly catalogs, celebrated the 150th anniversary of the monumental, horseshoe-shaped avenue, which was officially opened by Emperor Franz Josef on May 1, 1865. Among those joining in the sesquicentennial birthday festivities were the Belvedere, where paintings and decorative arts appeared under the title Klimt und die Ringstrasse (with more Ring than Klimt, notably); the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek and the Wien Bibliothek im Rathaus, which presented books, photos, maps, and other documents of wide ranging cultural-historical significance; and the Jewish Museum, which drew attention to the formative role played by the city’s Jews in the later nineteenth century. Related too was a section at the Vienna Biennale in the Museum für Angewandte Kunst featuring speculative designs for the future of the Ring.[1]

The Wien Museum for its part focused on architecture and urbanism in Der Ring: Pionierjahre einer Prachtstrasse (translated on the wall text as Vienna’s Ringstrasse: The Making of a Grand Boulevard).[2] With extensive holdings of paintings, decorative arts, and architectural artifacts, the municipal history museum on the Karlsplatz regularly mounts shows such as this one with an art and visual culture emphasis. Recently, the museum’s focus has fallen on the later nineteenth century. Der Ring followed closely on the heels of a major exhibition about Vienna’s world’s fair in 2014, and another one on the painter and cultural celebrity Hans Makart in 2011.[3] As a Ringstrasse-era trilogy, these exhibits together amount to an expansive survey of Viennese culture during the boom years of the 1860s and 1870s, when the city underwent urban expansion at the same time as it experienced the rise of a liberal middle class, the growth of industrial production and a market economy, and expanded consumption of art and design.

For Anglo-American scholars accustomed by Adolf Loos or Carl Schorske to thinking of the Ringstrasse as a conservative foil to fin-de-siècle modernism, these exhibitions and publications provided welcome opportunities to view the period on its own terms and from different interpretative perspectives. The Wien Museum curator responsible for Der Ring, Andreas Nierhaus, made clear his awareness of a scholarly legacy—he singled out in particular the foundational, multivolume study of the 1970s Die Wiener Ringstrasse: Bild einer Epoche—and his intention to explore new territory.[4] Evidence of a novel approach was found immediately in the unusual parameters of the exhibition. Rather than offering a full overview of the Ring and its architecture, completed over roughly three decades, the show instead was restricted to a brief period described as the “pioneer years,” lasting from 1858, when work got under way following an imperial decree, to the 1865 opening ceremony. During these first seven years, few of the boulevard’s iconic public buildings had begun to be constructed—only the Votivkirche and Hofoper had cornerstones laid, while the Rathaus, Hoftheater, and all the rest remained in the future—but plenty of planning, debate, competition, and the vast work of demolishing the old city walls had already taken place. By limiting itself in this way, the show set its sights less on the actual buildings and more on the preliminary negotiations and preparations that are necessarily part of large-scale urban development.

A second indication of a unique perspective was given in the label that greeted visitors at the entrance. Following introductory statements about the general historical and architectural importance of the Ringstrasse, the text presented an idea with fresh interpretive potential: The “drawings, plans, models, photographs, and paintings” on display in the exhibition, it pointed out, “are more than mere illustrations of the planned and the built. They deal with media of a distinctive order, which were created for a specific purpose. Their visual language and application produce varying meanings of that which they represent.” Visitors were thus encouraged to pay close attention to the visual techniques by which architecture and urban space were illustrated and how these techniques served to convey particular messages about the new city. The emphasis on media made sense. If this was to be an exhibition about plans and debates more than finished buildings, then it followed that attention to techniques of representation would be crucial to understanding how conversations about the future of the city played out.

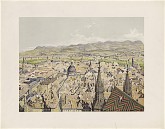

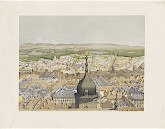

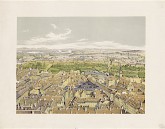

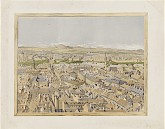

The inquiry into media was supported by a rich and varied collection of original objects. The galleries were amply populated with renderings, maps, books, models, and building fragments both large and small, monochrome and colorful, hand-drawn and mechanically produced, sober and evocative. In the first display area, a hall outside of the main galleries, things got off to a strong start (fig. 2). An enormous wood model of the city made in 1852 occupied the floor (fig. 3). Behind this hung an equally vast map from 1778 on which each one of the city’s buildings was illustrated in slightly tilted aerial perspective, like a hand-drawn Google Earth view. From the ceiling hung a 9½-foot-long panorama, created around 1830, looking across the rooftops of the city. And resting on a long display table was a set of four chromolithographic prints from 1857 that together formed another panoramic vista, this one staged from the city’s highest point atop the tower of St. Stephen’s cathedral (fig. 4). Together, these objects presented a varied, visually engaging set of impressions of the cityscape before the Ring.

Labels in this initial section drew attention to the representational techniques of the different objects. The chromolithographs, for example, were explained through a helpful comparison with the medium of photography, likewise invented in the 1830s. Chromolithography, the text noted, resembles “hand colored drawing” and lacks the “immediacy” of photography but is able to provide a greater “visible density of information.” Indeed, the chromolithographs on display here bore out these observations, showing an evenly lit, super-real clarity of detail, uniform from edge to edge, that differs from the atmospheric variation and optical distortion of a photograph. Label texts also spoke to what the images revealed about the urban character of the city. The model, map, and panoramas all showed central Vienna as a tight bundle of buildings and narrow streets hemmed in by massive fortifications. The images provided clear evidence of what the exhibition described as a condition of “maximum congestion” reached in Vienna by 1858—the population of the inner district was three times greater than today!—and that nothing was to be done at that point but demolish the old walls and expand into the surrounding open land of the glacis.

Following this prelude, exhibition visitors rounded a corner and entered the main gallery (fig. 5). Here the strong design qualities of the installation first became fully evident. Amid a dense array of framed images, hung from walls and ceiling and laid out on steel tables, the space was punctuated at irregular intervals by large, strongly colored text panels. These provided not only effective orienting markers, but also energetic accents against the grey and black surfaces that otherwise dominated. Particularly felicitous was the blushing pink-purple color of the labels, which cleverly evoked the morning sky and the metaphorical dawn of the new era. The same design language was used for the catalogue. The sunrise glow washed across the book’s cover and bled faintly from the spine onto the inner edges of the pages, as if the publication itself had been infused with a touch of the Ringstrasse’s optimistic light.

At the entrance to the main gallery, the exhibition narrative turned to the event that most clearly signaled the inauguration of the Ring project, the master plan competition held in early 1858. As in the previous section, here again the techniques of representation stood out. The first object confronting visitors was a rendering about seven by six feet in size and emblazoned in gothic script with the title “isometric projection of various areas of the city” (fig. 6) Produced by the Viennese architectural partnership of Eduard van der Nüll and August Sicard von Sicardsburg, this pen-and-watercolor drawing showed special compositional inventiveness. The image was divided into four frames, each of which contained an aerial view of the boulevard at different points along its route. Buildings and landscape features were rendered with crisp ink lines and pale colors, while streets and other open spaces were left as a void of plain paper. Architecture thus appeared to float against an immaterial ground—a striking visualization of the ideal city of the future. The exhibition label rightly judged van der Nüll and Sicardsburg’s image to be “the most graphically impressive document in the whole competition.” Together with a similarly sized plan in bright watercolors hanging next to it, the isometric drawing suggested that the success of the pair was based at least in part on their ability to produce distinctive presentation imagery.

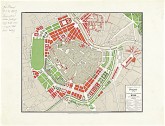

On an opposite wall hung a cluster of master plans by seven of the competitors whose submissions were identified by the jury for further consideration (fig. 7). Notable here was the standardized format of the plans, which were intended for exhibition and publication. The uniformity of size (26 x 31 cm) and basic color-coding (orange for new buildings, green for parks, grey or beige for existing buildings) allowed for easy reproduction and quick legibility. A lay audience could comprehend at a glance the salient differences in what each plan proposed: what was to be changed and what left alone, how much green space, how much area devoted to institutional buildings and how much to housing.

Although no single winner was chosen, certain architects emerged from the competition more successfully than others. Among them was Ludwig Förster, whose influence had much to do, it seems, with his skilled utilization of publicity. Described here as “supremely professional in dealing with media and the public,” Förster had founded the influential Allgemeine Bauzeitung [General Building Newspaper] in 1836, was an early adopter of photography (a Daguerreotype portrait of the architect from 1845 appeared here), and was among the first public advocates of expansion, exhibiting his own plans already in 1839. Following the 1858 competition, Förster was appointed to the state committee that digested the various proposed master plans into a final blueprint for expansion.

Next, the exhibition turned to preparations for construction. A section titled “Bastions and Glacis: The Demolition of the City Walls as Media Event” consisted of photographic images of the city walls taken by the State Printing Office just before and during demolition (fig. 8). These remarkable pictures captured a vanishing face of the city. Precisely focused and composed, they gave a vivid impression of the size and solidity of the fortifications, which could be crossed only by narrow bridges over deep moats and through imposing gates built into the walls. The photos recalled the powerful visual and spatial presence of the fortifications in the city before 1858, a presence equal indeed to that of the new boulevard that would replace them. Demolition, these images made clear, altered the city as fundamentally as did new construction.

In addition to the media emphasis, here the theme of labor also came into focus. Most of the aforementioned documentary photographs were eerily devoid of people, as if the city had been evacuated in anticipation of the impending upheaval. The emptiness of the images belied, however, the vast workforce required to carry out the demolition. To support this point, the exhibition included a pair of xylograph prints from 1862–63, presumably made for publication in illustrated magazines, that gave some sense of who and what was involved in the work (fig. 9). The xylographs show low-wage day laborers, men and women, dismantling the fortifications brick by brick with pickaxes and wagons. Another exhibited image of laborers appeared on the cover of the piano score of Johann Strauss’s “Demolirer-Polka,” written in 1862 and performed in local dance halls. Such pop culture ephemera testified to the imprint of the ubiquitous wrecking crews on the Viennese cultural imagination during the period.

With rubble cleared and the ground prepared for construction, the exhibition shifted its attention to buildings. Subsequent sections were devoted to the Votivkirche; to early housing, including Theophil Hansen’s Heinrichhof apartment building; to the competition for, and construction of, the Hofoper; and to public spaces, including the Stadtpark and the Schwartzenbergplatz. If a visitor felt some of the initial excitement dissipate at this point in the exhibition, it was perhaps because the material became more familiar as the attention turned toward the buildings and spaces that form today’s image of the Ringstrasse. Diminished too was some of the earlier narrative focus on media and representation. That said, the quality of the objects remained exceptional. Among the remaining highlights were a tall presentation drawing by Ferstel of the Votivkirche, its towers soaring against a sky of swirling clouds; watercolor renderings by Hansen of his Renaissance-inspired decorations for the interiors of the Palais Todesco; a pair of insouciantly muscular terracotta hermae rescued from the façade of the Heinrichhof before the war-damaged building was demolished in the 1950s (fig. 10); and an encyclopedia of urban statistics with colorful pictorial tables suggestive of the informational graphics later developed in Vienna by Otto Neurath. One pleasant surprise was a competition drawing by a 22-year-old Otto Wagner for the Kursalon in the Stadtpark. If our tendency is to think of Wagner only as a fin-de-siècle radical, this little pavilion reminded us of the extraordinary length of his career, his sustained engagement with the Ringstrasse, and his persistent inclination toward Renaissance-inspired classicism, which inflected his better known work around 1900 as well.

A brief, penultimate section about the festivities of the opening ceremony—fittingly another example of the multiple forms of publicity used to promote the Ring—was followed by a final room devoted to twentieth-century reactions. Rather than an integral conclusion, this felt like an addendum. The selection of responses was limited (Adolf Loos, but no Otto Wagner), and the jump ahead in time was out of keeping with the otherwise tight chronological focus of the exhibition. In a show on the beginnings of the Ring, it did not entirely make sense to discuss responses to the completed project. More satisfyingly, the final room included a table at which visitors could browse a selection of Ringstrasse literature. Older books, including Schorske’s Fin-de Siècle-Vienna, were included here alongside the new crop of illustrated catalogs and essay collections. More than just a nudge toward the gift shop, the display provided a useful chance to take stock of the current state of research and criticism. Visitors left with a reminder that Der Ring and all the other anniversary exhibitions of 2015 represent a significant output of new work and impetus for further expansion of perspectives on the architectural and cultural history of modern Vienna.

Eric Anderson

Assistant Professor of Art History and Visual Culture

Rhode Island School of Design

eanderso02[at]risd.edu

[1] Alexander Klee, ed., Klimt und die Ringstrasse / Klimt and the Ringstrasse (Vienna: Belvedere, 2015); Michaela Pfundner, ed., Wien wird Weltstadt: Die Ringstrasse und ihre Zeit (Vienna: Metroverlag, 2015); Harald R. Stühlinger, ed., Vom Werden der wiener Ringstrasse (Vienna: Metroverlag, 2015); and Gabriele Kohlbauer-Fritz, ed., Ringstrasse: Ein jüdischer Boulevard / A Jewish Boulevard (Vienna: Amalthea, 2015). A related English-language publication with essays by many of the same authors is Alfred Fogarassy, ed., Vienna’s Ringstrasse: The Book (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2015).

[2] See also the accompanying catalog, Andreas Nierhaus, ed., Der Ring: Pionierjahre einer Prachtstrasse (Vienna: Rezidenz Verlag, 2015).

[3] Wolfgang Kos and Ralph Gleis, eds., Experiment Metropole 1873: Wien und die Weltausstellung (Vienna: Czernin, 2014); and Ralph Gleis, ed., Makart: Ein Künstler Regiert die Stadt (Munich: Prestel, 2011). See also Jane Van Nimmen, “[Review of] Makart: Painter of the Senses and Makart: Ein Künstler regiert die Stadt” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11:1 (Spring 2012) http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring12/makart-painter-of-the-senses.

[4] Renate Wagner-Rieger, ed., Die Wiener Ringstrasse: Bild einer Epoche, 11 vols. (Vienna: Böhlau, 1969–1980).