The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Sibelius and the World of Art

Ateneum Art Museum, Helsinki, Finland

October 17, 2014–March 22, 21015

This past fall and winter, the Ateneum Art Museum mounted a sprawling, multisensory exhibition, Sibelius and the World of Art, to celebrate the legendary Finnish composer, Johann Christian (Jean) Sibelius (1865–1957), on the 150th anniversary of the year of his birth. Over 200 paintings, sculptures, and objects were on view, many for the first time, and visitors could listen to recordings of Sibelius’s compositions on audio tapes or in each of the galleries. The display included art from the maestro’s private collection and personal items from his home, Ainola, near Lake Tuusula. With the composer having been on the list of the most famous Finns for decades, it is surprising that this was the first exhibition of its kind.

Ateneum curators Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff, Timo Huusko, and Riitta Ojanperä launched their major research project in 2011 to explore how art influenced Sibelius and the ways in which his music affected artists and their work. They organized the exhibition around eleven themes: The Image of Sibelius, Youth, International Sibelius, Fantasy and Myth, Finlandia, Ainola, Portrait Gallery, Into the Woods, Symphonic Landscapes, Melancholy, and the Sibelius Monument. A banner on the front of the museum, with a reproduction of the composer’s face overlaid by wedges of six different colors, suggested Sibelius’s synaesthesia, a neurological phenomenon that associates colors with sounds (fig. 1).

One gained a sense of the international maestro’s singular magnitude upon approaching the exhibition’s entrance on the second floor of the museum. At the base of the stairs was a spotlight bronze bust of the mature, mustached composer in a suit (1909, Antell Collections, Ateneum) by John Munsterhjelm, with Sibelius’s left thumb tucked in the sleeve hole of his vest and a lock of hair tumbling across his forehead (fig. 2).

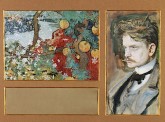

The composer was the subject of many artists’ portraits, thirty-seven of which appeared in the first room in “The Image of Sibelius.” Each generation represented the cultural luminary from the 1890s onward, from the young bohemian artist to the solemn senior. The best known depictions are those by Akseli Gallen-Kallela from 1894, such as his painting, En Saga (Jean Sibelius and Fantasy Landscape) (Ainola Foundation, Järvenpää), featured on the catalogue cover (fig. 3). The artist created the piece upon hearing Sibelius’s composition of the same name. This is a Gauguinesque attempt to capture vision and reality in a single work, separated into three sections. The right-hand panel is a half-length portrait of Sibelius in delicate watercolor, with a shock of unruly hair, slightly curled, reddish mustache, and icy blue eyes. The upper left-hand panel, an enigma with its snowflakes, ripe fruit on trees, and running black cats, is meant to portray musical inspiration, a kind of mental projection of Sibelius’s tone poem, En Saga (1893). Psychologically, it is one of the composer’s most profound works. Sibelius chose not to add a score to the picture in the third panel, but hung the work in a central place in his home throughout his life.

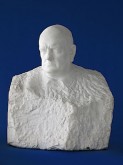

Rather than cased individually, ten busts and a small, half-length figure were displayed together on an open, low platform (fig. 4). Of this group, Wäinö Aaltonen’s white Carrara marble bust (1935) with its allusions to eternal values, is more firmly associated with Sibelius than with any other work of art (fig. 5). Aaltonen sculpted the slightly over life-size piece in honor of the composer’s seventieth birthday. One can see Sibelius posing for the sculptor in the enlarged photographs on the wall (fig. 6). The refined head of the bald man, with closed, stern lips and penetrating eyes, emerges from a rough, rectangular monolith. The impression of organic growth and vigorous creative power is Rodinesque. Because the State funded the piece and the national art collection acquired it, the bust became a kind of official portrait of Sibelius in its time.

On the other side of the gallery from the sculpture platform, on two suspended, overlapping, translucent screens, were silent, moving images of Sibelius (see fig. 4). Finns immediately recognized the composer in his hat and coat, even in this ghostly form, having seen this film clip of him walking in the woods many times.

One of the most compelling areas of this gallery, near the introductory label in Finnish, Swedish, and English, was a flat case featuring eight portraits of Sibelius in popular media (figs. 7, 8). In the upper left was the December 3, 1915 issue of the satirical magazine, Fyren, featuring cartoons of Sibelius over the years to commemorate his fiftieth birthday. The cover portrayed him as Väinämöinen, the central character in the national epic, Kalevala, a wise, old man with a potent, magical voice. The caricature is based on two famous works of art that represent Finnish imagery at its most typical. The body is borrowed from Johannes Takanen’s sculpture (1873) in Monrepos Park and the landscape is a pastiche by Albert Edelfelt in The Tales of Ensign Stål on which the lyrics of the national anthem are printed. In the center of the case is color lithographic caricature of Sibelius (1904) by Helio Aspelin. In both this piece and the one hundred mark banknote (released in 1986) in the upper right of the case, we see the composer’s unruly hair, multiple vertical wrinkles between the eyebrows, and often repeated typical furrows on his forehead.

Visitors descended ten steps into the next room, a small gallery featuring works related to Sibelius’s youth, when he aspired to be a violinist. His empty violin case was on display, along with works depicting musicians playing stringed instruments, such as Ellen Thesleff’s Violin Player (1896, Ahlström Collection, Ateneum) (fig. 9). As artists desired to depict “musicality” in painting, new palette practices emerged in early Finnish modernism. One, color asceticism, is evident in Thesleff’s piece, in which the palette is reduced to black, brown, and white.

While the section “International Sibelius” had few art works on display, it drove home the global nature of the composer’s life with its two-wall map identifying the forty-one cities to which Sibelius travelled between 1889 and 1931, beginning and ending with Berlin, where he first studied and where his publisher was located (figs. 10, 11). His international breakthrough came in the early 1900s in Nordic countries, Germany and Great Britain, and he later achieved fame in the U.S. and Japan. Also on display was Sibelius’s hat and collar trunk near twenty-one pieces of paper ephemera, such as his passport, in a flat case.

In this gallery, too, was a listening chamber backlit by blue light (fig. 12). Projected in white on the front of the free-standing cube was a portion of the score to Finlandia, Opus 26 (1899). Inside the grey-carpeted room lined with white velvet walls and continuous grey bench seating were twenty-four light blue pillows where visitors could listen together to the symphonic poem that runs anywhere from 7 ½ to 9 minutes (fig. 13). Sibelius composed the orchestral piece for the Press Celebrations of 1899, a covert protest against increasing censorship from the Russian Empire. In seven sections, it evokes the national struggle of the Finnish people with rousing, turbulent music and a serenely melodic conclusion. The Finlandia Hymn in the middle is particularly famous and has been borrowed in many contexts. When Finland gained its independence in 1917, Sibelius’s standing was further strengthened. After lyricist Veikko Koskenniemi added words in 1941, this hymn became one of the most important national songs of Finland.

There were sixteen pieces in the “Fantasy and Myth” room, hung in a dull ring-around-the-bathtub manner (fig. 14). At the end of the nineteenth century, artists were increasingly interested in spiritual movements, such as theosophy, Tolstoyism, and esoteric sects. Recurring themes in their work were fantasies about a lost Golden Age, natural forces, the animal kingdom, swan symbolism, and ancient mythology. Finnish artists, both visual and musical, found inspiration in the timeless, mythical world of Kalevala, and Sibelius’s breakthrough work was about the tragic life and early death of Kullervo, the ill-fated son of Evil, in the epic. Kullervo, Opus 7 (1892) is a five-movement, choral symphony for full orchestra. It was the composer’s first successful piece and in distinctly Finnish style. On view in this section were (fig. 14, left to right), Magnus Enckell’s Fantasy (1895, Herman and Elisabeth Hallonbad Collection, Ateneum) (this hung in Sibelius’s home; the composer admired its white and black swans) and three works by Gallen-Kallela: Conceptio artis (1894, Ateneum), Kullervo Herding His Wild Flocks (1917, Ateneum), and Aallotars (Billows’ Daughters) (1909, private collection).

The next two galleries, long hallways really, were awkward spaces for display, but curators made the best of them with objects in shallow wall cases. From the start, Finlandia, probably the best-known piece by Sibelius for Finns, was significant in boosting national self-esteem. It acquired international fame when the Philharmonic Society of Helsinki performed it, with a tour culminating in the 1900 Paris World’s Fair (presented there under the title, La Patrie). In the “Finlandia” corridor were material culture pieces such as five album covers of Sibelius’s records, four 45s, a CD, a cartoon about Finlandia vodka, seven pieces of sheet music, Gallen-Kallela’s poster for the concert at the Trocadéro, small reproductions of Lennart Segerstrale’s frescoes for the Bank of Finland (1938), stills from the film, Unknown Soldier (1955), and a jubilee medal (1999) and poster commemorating the 100th anniversary of the composition (fig. 15). The piece has been perennially popular, and was broadcast at Senate Square Helsinski when Finland won the Ice Hockey World Championship in 2011.

“Ainola” concerns the beloved home of Sibelius and his wife (née Aino Järnefelt) (fig. 16). The couple moved there in 1904 on completion of the house designed by Lars Sonck. Here were enlarged photographs of various rooms and the Sibelius family mounted on foam core, as well as selected personal belongings such as the composer’s white suit, handkerchiefs, linens, lace, scissors, a thimble, sewing kit, ashtrays, and small paintings. Next was a narrow transitional space displaying a large screen with a projection of a symphony playing Sibelius’s music, but there was no label (fig. 17).

The “Portrait Gallery” housed seven paintings of some of Sibelius’s friends, such as Albert Edelfelt’s portrait of Aino Ackté (1901, Antell Collections, Ateneum) (fig. 18). Ackté was the first internationally famous Finnish opera star. She promoted Sibelius’s compositions and Finnish music abroad. Oscar Parviainen, a relatively unknown painter in Finnish art history, was deeply influenced by Sibelius’s work and gave him several of his paintings, including Invocation or Child’s Death (ca. 1910, Ainola Foundation), moved by news of the death of Sibelius’s daughter Kirsti in 1900. In turn, Sibelius dedicated two of his piano compositions to him, and hung Parvianen’s large canvas in front of his grand piano. On display here was the artist’s Self-Portrait in Electric Light (1914, Herman and Elisabeth Hallonb;ad Collection, Ateneum) (fig. 19); he often painted at night with artificial light. The composer’s circle of friends also included conductor and composer Robert Kajanus, who directed many premieres of Sibelius’s orchestral works for the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra. Other associates were artists Pekka Halonen and Eero Järnefelt, Aino Sibelius’s brother, both of whom lived nearby and many of whose paintings hang in Ainola.

A distinctive feature of Finnish art is the significance attached to the forest, seen as a cherished and even mythical place for Finns, as expressed in the section, “Into the Woods.” Poets and painters often depicted the rowan tree, sacred in the Kalevala. In Parvianinen’s Foliage (ca. 1910), the screen of red leaves provides a protective network against a shimmering, gold background (fig. 20). As a tribute to the magnificent pine trees at Ainola, Pekka Halonen presented Winter Forest (1915, Ainola Foundation) to Sibelius for his fiftieth birthday (fig. 21). The snow-covered branches contrast with the ruddy trunks and dense, dark bushes. The painter and composer shared an intense, affective relationship with nature that gave them endless inspiration. Sibelius wrote intimate songs to trees. In another painting, Great Pine of Kotavuori (1916, Atenueum) Halonen produced a close-up of a massive, fallen tree with sinuous, bare, red branches (fig. 22). Also included here was a high-definition video, Memory Trace (2014) by Hannu Pakarinen, of the Ainola estate (see fig. 22). The piece was projected on an uneven surface composed of nineteen vertical squares (each about 3 x 3 inches) and thirty-four horizontal squares of birch wood. This work gave a contemporary view of Sibelius’s retreat and injected moving vitality into the gallery.

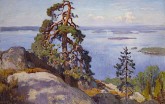

The theme of the power of nature continued in “Symphonic Landscapes” where eleven paintings were on view. Landscapes dominated by broad vistas, faraway horizons, and high vantage points could be considered symphonic and notably Finnish. Artists often modified landscapes to express a state of mind, simplifying or altering them, or enhancing nuance. Sibelius internalized his nature experiences as emotional evocations and as structures for his symphonies. He visited the Koli heights with his brother-in-law, Eero Järnefelt, in 1909, then wrote his Fourth Symphony, evoking the magnificent scenes he observed. Järnefelt scaled the Koli heights dozens of times and painted the views repeatedly, as in his Landscape from Koli, (1928, Säästöpankki Oy Fine Arts Collection, Ateneum) (fig. 23).

In the “Living Room” one could sit at a table and peruse thirteen publications about art and music and listen to Sibelius’s work with headphones (fig. 24). Also in this space were furniture from Ainola—a lamp, the composer’s favorite chair, and an end table. Here, too, was an old black desk telephone. Visitors were invited to pick up the receiver and hear a recording of Sibelius giving conductor Nils-Eric Fogstedt instructions over the telephone for a performance of the composition, King Kristan II, in the early 1950s. One of the oddest sections here was a silent color video of Sibelius’s violin, rotating in a spotlight against a black background like a sacred object. It is uncertain whether Jacob Steiner made the instrument, as its label says, but luthiers agree that it was probably made in the eighteenth century with much older wood. Sibelius’s uncle gave it to him in 1886, after receiving it from his brother who bought it at a flea market in St. Petersburg. Today, the violin is owned by Sibelius’s granddaughter, who got it from him when she was twelve.

The masterpiece of the exhibition, Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Lemminkäinen’s Mother (1897, Antell Collections, Ateneum) was in the area called “Melancholy” (fig. 25). The artist originally named the painting Lemminkäinen in Tuonela after the second movement of Sibelius’s composition about the Kalevala. Lemminkäinen was a war hero and womanizer who died when he tried to shoot the mystical Swan of Hell, seen in the upper left, to find the secret of life and death, which it guards. Lemminkäinen lies at the edge of the black, infernal river, where his mother tends to him, sending a bee to fetch a magic healing balm from a golden fountain. The painting is a collision of the real, with its carefully delineated bones, skulls, and candles, and the abstract and decorative, with the flat, granular patterns of the shore pebbles, red moss-covered rocks, the hero’s curling locks of hair, and especially, the stylized golden sun rays. An etching of the same scene, reversed (1905/1922) was on view here, too.

Melancholia was thought to be an exalted state of mind, necessary for artists who wanted access to the unconscious to depict a world beyond the visible one. Also in this gallery was a case of lovely small bronzes (fig. 26). Second from left was Knut Jern’s Valse triste, (1923, Ainola Foundation) of a nude woman with bobbed hair swirling a cloth around her back and legs. (One could listen to Sibelius’s Valse triste, Opus 44, No. 1 [1903] in the exhibition.) The other four pieces were of young couples embracing and offering comfort, as in the fourth work, Ville Vallgren’s The Flowers of Love (Water-Lily Dish with Two Figures) (1894, Hoving Collection, Ateneum) and the fifth one, his Two Young People (1893, August and Lydia Keirkner Fine Arts Collection, Ateneum), in which the frontal woman slumps and covers her brow with her forearm. In a case by itself was Emil Halonen’s Grief (1909, Ainola Foundation), of a kneeling woman bent over (fig. 27). She holds her hands to her face as her long hair cascades over her head. On the wall in the background, one could see Parviainen’s heartbreaking Invocation or Child’s Death (ca. 1910), mentioned earlier.

The last gallery was devoted to the Sibelius Monument, completed by Eila Hiltunen in 1967, and still one of the most famous sights in Helsinki (fig. 28). Located on a rocky outcrop in the middle of a park, the abstract work of steel pipes over eight meters tall has been likened to organ pipes, a cathedral rising to the heavens, and birch tree trunks. Sibelius composed two works for the organ, both of which could be heard in the gallery while viewing scale models of the sculpture. One of these was Funeral Music (1931) that the maestro created for the funeral of his friend, Akseli Gallen-Kallela.

When the Sibelius Society, founded after the composer’s death in 1957, proposed a monument, a heated debate ensued. Would it be more appropriate to produce a likeness of the man or something representative of a modern movement? Hiltunen was one of the pioneers of new Finnish sculpture in the 1960s and welded most of the individually fashioned pipes herself. Later, a separate relief of the composer was added to the design.

Strangely, at the end of this narrow room are two videos that seem out of place, as though the curators couldn’t determine where else to put them in the exhibition. Both feature Valse triste (1903), one of Sibelius’s signature orchestral works, to demonstrate the unabated popularity of the work. One is an excerpt of Bruno Bozzetto’s animated film, Allegro Non Troppo (1976), in which a cat wanders into the ruins of a large house, remembering those who inhabited it before the structure is demolished. The other is of Finnish ice skaters, who won a silver medal at the Olympics performing to the score in the early 1990s.

On the whole, Sibelius and the World of Art was an enlightening and engaging show, and of great importance to Finns who cherish the composer as one of their finest and best internationally known creators. While the trilingual labels benefitted foreign visitors, the amount of space they occupied meant that they had to be brief and sometimes there was no information beyond simple captions of artist, title, date, and collection. Although the exhibition was not yet scheduled to travel (and it surely should), it was accompanied by a hardbound, lavishly illustrated color catalogue in Finnish, Swedish, and English editions. This will surely be the definitive publication on the composer and his relationships to art and artists for decades to come.

Theresa Leininger-Miller

Associate Professor, Art History

University of Cincinnati

theresa.leininger[at]uc.edu