The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Peace Breaks Out! London and Paris in the Summer of 1814

Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

June 20–September 13, 2014

O Peace! And dost thou with thy presence bless

The dwellings of this war-surrounded Isle;

Soothing with placid brow our late distress,

Making the triple kingdom brightly smile?

Joyful I hail thy presence; and I hail

The sweet companions that await on thee;

Complete my joy—let not my first wish fail,

Let the sweet mountain nymph they favourite be,

With England’s happiness proclaim Europa’s liberty.

—Sonnet “On Peace” written by John Keats (1795–1821) in 1814

On the bicentenary of a forgotten peace, Sir John Soane’s Museum in London held a modest but intriguing exhibition about the summer of 1814 when Europe celebrated the cessation of hostilities between Britain and France after the Treaty of Paris following the fall of Napoleon I. The premise of this exhibition was that one needs to look at the events of 1814—and the false promise of lasting peace that they offered—in order to understand the origins of the Great War that began in 1914. Co-curated by historian Alexander Rich and Jerzy Kerkuć-Bieliński, Exhibitions Curator at the Museum, the show took place in the Soane Gallery, that is, two rooms on the second floor of what had been the home (built 1823–24) of Sir John Soane (1753–1837), the architect for the Bank of England and Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy. Based primarily on Rich’s private collection supplemented by pieces from the museum and several other lenders, the exhibition of over 100 rare works included paintings and prints that depict festivities in London and across the United Kingdom, Soane’s Napoleonica (objects that belonged to Napoleon and his collaborators), drawings of Paris showing the architectural changes that took place under Napoleon’s government, tokens for the Peace of Paris, a satirical depiction of Englishmen visiting Paris by a French illustrator, and other material culture. These were arranged in six major groupings.

The peace of 1814 and the Congress of Vienna in 1815 laid the geo-political framework, of the European empires that would dominate much of earth until World War I. This balance of power was known as “The Concert of Europe.” The Allies who celebrated the signing of the Treaty in London would face each other as battlefield enemies again almost exactly one hundred years later. The peace celebrations left several legacies: the waltz as a dance became popular; Regency fashions changed; and the British, including Soane, travelled to Paris for the first time in years.

In the first room of the exhibition, nearly all of the objects were on display in cases illuminated electrically as well as by natural light from floor-to-ceiling windows (the latter open during warm weather) (fig. 1). There was a two-paragraph introduction on a slim wall panel to the left of the door (fig. 2).

Generally, two-dimensional pieces were in the three wall cases while prints and objects were in the three table cases and on one pedestal under a vitrine. Aside from the sole text label, “Most Glorious and good News” high on one wall, indicating the new era of peace, the layout was not initially apparent to visitors (fig. 3). Counterintuitively, one had to go to the right of the entrance to find the modest and visually weak beginning of the exhibition, with a mezzotint of the obese Louis XVIII in his coronation robes (1823) (fig. 4). One could then find an introductory text panel, “1: Most Glorious and good news.” The phrase, preceded by “Old England for ever!!,” comes from a printed handbill (April 7, 1814) announcing the entry of the allied armies into Paris. In the display case below the portrait were five medals commemorating events in the king’s life, a silver badge (the Décoration du Lys given to national guard members), and a musical score (fig. 5). The composition, “The White Cockade,” was about a knot of ribbons worn to show sympathy for the Bourbon dynasty.

The largest wall case, to the left of the entrance, featured mostly works on paper, in groups of five and ten, respectively. The first section, “2: O Peace!,” concerned the events and documents leading to peace in 1814 (fig. 6). In the lower left there was an etching of a thanksgiving service (Te Deum) in recognition of the ending of hostilities by the allied armies in Louis XV square on April 10. Above this was an etching of Napoleon’s abdication at Fontainebleau before his departure for Elba on April 20. On the same day that Napoleon signed his unconditional abdication (April 6), the “Senatorial Constitution” was passed, announcing the return of Louis XVIII and proposing a French constitutional monarchy; this broadside is in the middle of the case, along with the “Old England for ever!!” handbill. Next was a caricature of Napoleon in the form of a “hieroglyphic portrait.”

Napoleon’s abdication prompted jubilant celebrations across Great Britain and Ireland and general “illuminations” of towns and cities took place even before the end of April 1814. Buildings lit by candles or carbonic gas internally would illuminate transparencies affixed to their windows. On view were several related rare documents including an etching of the Excise Office as illuminated in June (fig. 7). The print is one of the very few pictorial records of an “illumination.” Another hand-colored etching with aquatint, Ackermann’s Transparency, is an illustration of the transparency exhibited on the thirty-feet high Ackermann’s Repository of Arts in September. It featured the goddess of Peace, the Allies’ standards, and the virtues of Temperance, Fortune, Faith Charity, Hope, Justice, and Providence. A fragment of an actual paper transparency, a precious bit of ephemera, was on view above this print.

Peace had never been celebrated on such a grand scale, with many festivities at a local village level. Regency England created a vast array of art and commemorative items, including porcelain, glassware, prints, medallic art, and jewelry (some of which was in the table case in the middle of the gallery and in the case opposite the door), as well as permanent architectural follies and monuments. In addition to a peace jug, tea sets, cups and saucers, a pipe bowl, a peace brooch, and an opera fan, also on view was an expensive, netted red silk purse given to “Gentleman” John Jackson, “The Emperor of Pugilism,” for sparring the Emperor of Russia in June (figs. 8, 9).

The last section of the large wall case contained items grouped under “3: Illustrious Visitors.” The Prince Regent, who had never been in the theater of war, was eager to associate himself with the Allied Sovereigns who had led their forces into battle and subdued Napoleon. He invited the Tsar Alexander I Emperor of Russia, King Frederick William III of Prussia, and Emperor Frances I of Austria to London for theater visits, a banquet, and a ball, and to receive honorary degrees from Oxford University. The latter event was depicted in two prints on view, one a French caricature and the other a satirical English print. Also on view were playbills on paper and silk, concert tickets, and gilt brass counters or tokens with portraits of the dignitaries. On the opposite wall was a large drawing of Lothbury Court at the Bank of England (1801) in pen and colored washes by Soane’s chief draftsman, J.M. Gandy (fig. 3). The Emperor Alexander, the Duchess of Oldenburg, the Prince of Orange, and their retinues entered the Bank via Lothbury Court (used primarily as a safe conduit for bullion vans) rather than the main entrance. The royal visit was a singular honor for Soane.

Section “4: The Grand Jubilee in Honour of Peace” appeared on the wall with the text, “Most Glorious and good News.” Authorities had hoped to hold the jubilee in the Royal Parks when the Allied Sovereigns visited, but difficult preparations postponed the date until the first week of August. The centerpiece in St. James’s Park was the Temple of Concord or the Grand Pavilion, complete with porches, oil paintings, transparencies, heraldic ensigns, inscriptions and trophies. Lit from within, the temple revolved slowly to display an allegorical cycle of war against an astonishing and extensive firework display. Other structures were a Chinese bridge, the Castle of Discord, and a pagoda, all of which, along with the Temple, were depicted in a hand-colored etching (a commemorative broadsheet) on view in the wall case on the left (fig. 10). Thousands of Britons milled about the parks, visiting over 400 booths and drinking great quantities of porter and bottled ale for over a week. Also on view were tickets to the Grand Jubilee and an etching of a scene of a spectacular mock naval battle on the Serpentine in Hyde Park during the celebration.

Section 5, in the back room, concerned “Travel to France in 1814” (fig. 11). France was closed to English travelers by Napoleon’s Continental System (or blockade) for about two decades, from the French declaration of war against England in 1793. The Treaty of Amiens offered a brief respite for visitors (March, 1802–June, 1803) until a decree of the French Republic halted such travel again. After the Treaty of Paris was signed on May 30, 1814, thousands of English people flocked to France by packet boats and stagecoaches. British visitors (including Soane) were “popping over the Channel like champagne corks.” Typically staying two to three weeks, they were eager to see city planning initiatives, new bridges, building refurbishments, and new construction, as well as to sample French cuisine. Mostly, the inestimable treasures plundered from defeated countries lured middle class travelers (not just nobility and educated gentry) who could now see this mass quantity in one place, at the Musée Napoléon (better known now as the Louvre), using newly available pocket-sized guide books. Foreigners had access free of charge to the museum where they could see more than 1,200 paintings from the Vatican and other European collections, as well as the sculptures, Laocoön and His Sons, Apollo Belvedere, and the Venus de Medici. On view were a map of Paris and a passport.

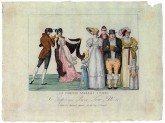

British visitors to Paris in the summer of 1814 were eager to see the latest trends, and some French artists mocked their style. In an anonymous etching and engraving, La Famille Anglaise à Paris (ca. 1814), a provincial English family visiting Paris stands rigidly in constricting, unflattering clothing (fig. 12). A Parisian couple, posing elegantly, looks askance at the six visitors. The woman wears an Empire-line dress with a Kashmir shawl of the type made fashionable by the Empress Josephine. Josephine amassed huge debts at Parisian outfitters, selecting clothing to complement the fabrics decorating the state apartments.

Although British, Austrian, Prussian, and Russian troops occupied Paris in the summer of 1814, the city continued to offer varied pleasures. In the etching and engraving, Le facheaux contretems ou l’anglais surprise par sa Femme, an attractive Parisienne (probably a courtesan) beckons a plump English squire toward a restaurant that advertises “private rooms” that were used for more than dining (fig. 13). Eels (sometimes metaphors for the penis) hanging outside the entrance, suggested the sexual encounters that could be had there. The caricatured, spindly, unfashionable Englishman’s wife stops him from entering the restaurant, however, twisting his ear as she scolds him.

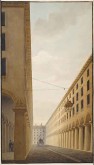

Although intended as a lecture drawing, it appears that Henry Parke’s view of the Rue de Colonnes from the Quartier Vivienne, 1819 (?) was never used (fig. 14). The overcast street view, empty except for a vehicle in the distance and a couple on the colonnaded pavement on the left, is one of the few examples of urban planning dating to the time of the Revolution, 1793–95. The elegant plan, based on a severe, Greek Doric style, was a precursor to Napoleon’s later redevelopments of Paris. The quarter was popular with British visitors because it is near the Louvre, and Soane himself stayed at No. 10 in the nearby Rue Vivienne in 1819. However, the drawing includes the open gutter in the middle of the street, and British visitors commented on that lack of sanitation disapprovingly.

Soane used Henry Parke’s drawing of the Place Vendôme, one of Paris’s most beautiful squares, in his third lecture at the Royal Institution in1820 (fig. 15). Based on Soane and Parke’s visit to Paris in 1819, it is a distant view of the column surrounded by four-story buildings and ant-scaled viewers at the base. Between 1806 and 1810, a monument based on the Trajan Column in Rome was made from 250 melted-down canons captured by the French from the Austrian and Russian armies. The bronze was used for bas-relief panels that showed the military successes of the Emperor from 1805 to 1807. Atop the column was a twelve-foot statue of Napoleon as “The Bringer of Peace.” After his abdication, a white Bourbon Royal Standard replaced the statue in April 1814. This view, then, looked much as Soane would have seen it in late August 1814 on his second trip to the city.

For his seventh lecture at the Royal Academy, Soane used the pencil and watercolor drawing, Royal Academy Lecture Drawing, The Arc de L’Etoile (de Triomphe) with a Comparative Elevation of the York Water Gate made by his Office (1820) to compare the Arc unfavorably with the Gate, saying that the small building would add more to the fame of architect Inigo Jones than it the Arc would offer to its architect, Jean Chalgrin (fig. 16). Chalgrin began the monument in 1806 but died in 1811 and the Arc was not completed until 1836. As an interim solution, and to herald Napoleon’s marriage to Arch-Duchess Marie-Louise in 1810, a facsimile of the completed Arc in wood and plaster was erected. That was the basis of this drawing.

The final section of the exhibition was “6: The Architect and the Emperor: The Self-Made Man, Soane and Napoleon.” The men held in common vision and talent that helped them rise from modest beginnings (Soane was the son of a bricklayer, and Napoleon began his career as an army officer), and they were both passionate about architectural urban improvement. Although Napoleon was an enemy, he was an obvious source of fascination for Britons, including Soane, who practically built a shrine to the Emperor with his collection of Napoleonica in his house-museum. On Soane’s trips to Paris in 1814 and 1819 he admired many of the structures Napoleon ordered, as well as his collection of the choicest European works of art.

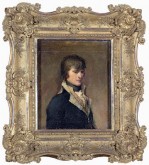

On view was a small portrait, the first real likeness of Napoleon to have been seen in Britain (fig. 17). Italian-British painter Maria Cosway, who esteemed Napoleon, hired the little-known Italian artist, Francesco Cossia, to sketch the young general at a dinner in Verona in 1797. So honored by the commission, Cossia declined payment. The bust-length portrait depicts the dashing, but serious, young leader in his military uniform looking downward against a neutral background. In this section were Napoleonic medals, an officer’s sword, and exceptional edition of Charles Percier and P. F. L. Fontaine’s book, Palais, maisons et autre edifices modernes dessinés à Rome (1798), presented to Josephine Bonaparte. The latter is probably a unique survival, distinguished by the additional hand-colored duplicate plates that accompany the monochrome illustrations.

Among the most personal items on view was a gold English mourning ring containing a lock of Emperor Napoleon’s hair (fig. 18). Elizabeth Balcombe, daughter of an official on St. Helena who befriended the emperor, had the ring made after Napoleon gave her several locks of his hair. Balcombe sent the memento to Soane after learning of his interest in the French leader. It was one of the architect’s most treasured private possessions.

At a time when so many museums are commemorating the one hundredth anniversary of World War I, this exhibition was a unique approach to the subject in an oblique way, shedding light on the peace between Britain and France that lasted from 1814 to 1914. It was the perfect time to showcase these rare and fascinating historical documents, images, and objects. However, it is regrettable that the display of them was not articulated in a manner immediately apparent to viewers (the six sections could have been itemized in the introductory text panel), and that the show did not travel and reach a larger audience. However, there is a slim, illustrated catalogue with essays by the co-curators and Gisela Gledhill available from the museum gift shop.

Theresa Leininger-Miller

Associate Professor, Art History

University of Cincinnati

theresa.leininger[at]uc.edu