The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Manet, inventeur du Moderne

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

April 5 – July 17, 2011

Catalogue:

Manet, inventeur du Moderne/Manet: The Man Who Invented Modernity.

Ed. Stéphane Guégan, with contributions by Helen Burnham, Françoise Cachin, Isabelle Cahn, Laurence des Cars, Guy Cogeval, Simon Kelly, Nancy Locke, Louis-Antoine Prat, and Philippe Sollers.

Paris: Musée d’Orsay and Gallimard, 2011.

336 pages; 280 illustrations; key dates; list of exhibited works; selected bibliography; index.

Available in French and English editions.

€ 42.

ISBN: 978 2 35 433078 1

Once you actually managed to stand in front of most of the Manet paintings gathered at the Orsay this summer, the rewards were endless (fig. 1).[1] In painting after painting, you were reminded what made him one of the nineteenth century’s most gifted and nuanced artists. The bravura with which he applied paint lends his world an elegant ease that emerges less as reality than as fraught dream and wish. The unusually stark contrasts in light and dark color he employed to destroy centuries’ old rules of academic decorum morph into social distinctions as much as aesthetic ones (struggles over visibility and invisibility, identity and non-identity, subjectivity and objectivity, order and disorder, hierarchy and chaos). Ordinary things and everyday scenes parade before us as poignant reminders—distillations—of a world of eroding distinctions, such that politics and fashion speak the same dialect. Here, abbreviation connotes informality, but also a generalized loss of meaning. Everywhere, there is the wondrous, and endlessly complex, world of modern Paris that fascinated Manet, and he remains one of our sharpest translators of nineteenth-century modern life into early modernist form.

Many, if not all, of these crucial aspects of Manet’s oeuvre and central place in the nineteenth-century canon were on vivid display at the Musée d’Orsay’s most recent Manet retrospective this summer, provocatively entitled Manet, inventeur du Moderne (translated by the museum as Manet: The Man Who Invented Modernity): “Manet is modern primarily because he embraces, as much as Courbet yet differently, the changes in the media that marked his era, and the unregulated circulation of images; secondly because imperial France, the backdrop to his developing career, was modern. And finally because the manner in which he challenged the masters of the Louvre was modern, extending beyond his militant Hispanism,” proclaimed the English press release that accompanied the exhibit.[2] This is an ambitious program, to show Manet’s modernity reflected not just in his selections from bits and pieces of modern life, but also in his pictorial means, including his awareness of the erosion of artistic traditions as they encountered, and were laid low by, the new media of his day such as photography.

In this regard especially, the exhibit departed expressly from its 1983 Paris and New York predecessor, an exhibition that has often been characterized as among the last great efforts to rescue a formalist and connoisseurship-based account of Manet towards a nascent socio-historical one in which the lived textures of modernity were tantamount.[3] But the 1983 retrospective nonetheless loomed large over the current enterprise, not just because the previous show remains unchallenged in its gathering of Manet masterpieces, but also because the 2011 exhibit became a memorial event to Françoise Cachin (1936–2011), the curator of the previous retrospective whose brief reflections on her show open the 2011 catalogue. Manet, inventeur du Moderne promised both a return to, and a departure from, our previous narratives of the artist, thus exemplifying in its very format the tension between the traditional and counter-traditional it portrayed as the hallmark of Manet’s art. But this heavy-handed rhetoric of temporal plasticity, often conveyed in brief, journalistic catchphrases that left much about Parisian late nineteenth-century modernity unexplained and unexamined, made for a show whose conceptual framework did not always conclusively match the great art on its walls.

The large group of 180 works on display, mostly but not exclusively by Manet, was divided by curator Stéphane Guégan into nine sections of roughly equal size. At times the paintings and works on paper in one section were presented together in one room, at times in two; and at times they continued around corners or in small nooks and passageways. But the wall texts and the gallery guide ordered the viewers into the specific rubrics even if the actual spaces did not. At the entrance to the show, visitors were greeted not by a Manet painting, but by Henri Fantin-Latour’s Homage to Delacroix of 1864, in which Manet is depicted as one figure among a group of fellow artists and writers, placing him within a network of avant-garde practitioners and refusing him singular status from the start. Visitors then followed a largely chronological exhibition. Section one introduced Manet’s teacher, Thomas Couture, with a large number of canvases and studies, and included a nice selection of Manet’s early Italian drawings, ending in his 1860 portrait of his parents (fig. 2).

Section two, “The Baudelaire Moment,” grouped some of Manet’s first large-scale and perhaps most infamous paintings like Olympia (1863), The Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1862–63), Lola de Valence (1862–63) and The Street Singer (ca. 1862) with smaller works made in Baudelaire’s orbit (figs. 3–5). The show’s compare-and-contrast mode with other artists continued, including a large Portrait of Charles Baudelaire by Émile Deroy (1844) and several watercolors by Constantin Guys.

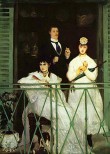

Section three covered most of Manet’s large-scale 1860s religious paintings, hung together in this format, I imagine, for the first time. Entitled “A Suspicious Catholicism,” it included Alphonse Legros’s The Calling of St. Francis of 1861 as a benchmark by which religious and modern experience could find common form (figs. 6–8). “From the Prado to the Place de l’Alma,” the subsequent section, chronicled the paintings Manet made after his 1865 trip to Spain, concluding with his infamous 1867 one-person show opposite the International Exposition: it included paintings like The Fifer (1866) and The Dead Torero (1864–65). The next section, gathered in the exhibition’s most spacious room, was devoted to one of Manet’s favorite models, Berthe Morisot. The Balcony of 1868–69, in which she is seen sitting pensively leaning over a green metal railing, occupied the central wall, allowing visitors the most expansive view onto any painting in the show. Several details of The Balcony also open the exhibition catalogue; with its portrayal of a much quieter and less provocative modernity than the naked Victorine Meurent in Olympia or the Déjeuner—a modernity of fashionability and self-display without sex and prostitution—The Balcony became the exhibition’s key to the new meanings of “the Modern” (fig. 9).

Section six, “Impressionism Caught in a Trap,” was stretched out over several smaller rooms and corridors along the left side of the exhibition space and was perhaps the most dispersed group of works. It dealt with Manet’s fraught relation to Impressionism, with his adoption of the style and simultaneous rejection of its new counter-establishment venues. The famous portraits of Nina de Callias (1873–74) and Stéphane Mallarmé (1876) were joined here by several 1860s and 1870s beach, harbor, and river bank scenes (fig. 10). The following section seven, “The Turning Point of 1879,” considered the consequences for Manet’s practice—in formal, iconographic and institutional terms—of the rise of opportunist republicanism in the late 1870s. Chez le père Lathuille of 1879 was the central painting of this section, but it included as well some of Manet’s late paintings and pastels of fashionable Parisian women such as The Amazon (Summer) of 1882—the painting that was, quite surprisingly, used on the cover of the catalogue (figs. 11 and 12).

Section eight was entitled “Less is More?” and devoted to Manet’s (late) still-lifes and their often daring abbreviations of brushwork and motif. The final section, “The End of the Story” (in French “La fin de l’histoire” expressed better the confluence of the “story” of Manet’s career and his successive attempts at “history” painting), included examples from the historical and political paintings of Manet’s entire career, stretching from The Combat of the Kearsage and the Alabama of 1864, to The Execution of Maximilian (1867–68), to his works on paper made during the Commune in 1871, to his two versions of The Escape of Rochefort of 1880–81. In particular, this final section underlined the fact that Manet’s art simply cannot be divided easily in terms of either genre or chronology.

The show thus included both plenty of old favorites and images less frequently seen in public, and certainly not often seen in public together. The room of Manet’s 1860s religious paintings was illuminating and a rare opportunity to see the full importance the theme held for him when the Olympia and Déjeuner scandals broke (even if one also wished to see Olympia hang again with Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers, as they did in the 1865 Salon); the three fragments from The Gypsies (1861–62 and ca. 1865–67) reunited were stunning, as was the row of Berthe Morisot portraits and the groups of later watercolors and watercolor letters. The exhibit ended in a few odd doublings that brought out a modern life painter more hesitant, even obsessive, than our traditional image of lightning fluency holds: the two portraits of Georges Clemenceau (both 1879–80) and Antonin Proust (ca. 1877 and 1880) each side by side; the two Escapes of Rochefort (1880–81), in different sizes and with a different prominence given to the boat and figures within each frame, show us a painter deeply concerned with the proximity between subject and viewer, with exactly how close he might rub our noses in the ideological fabric of modernity.

The exhibition deserved credit for engineering these moments. But were they enough? Many critics did not think so. How can any Manet retrospective deserving that designation leave out this much and substitute with somewhat “lesser” art, both by Manet and others? Hardly any of the great 1860s Spanish-style single figure paintings from Chicago or the Metropolitan Museum were there—and no Luncheon in the Studio, no Argenteuil (and so few of his most important “high-impressionist” paintings), no Nana, no Bar at the Folies-Bergère (and not much evidence of his café-concert interest). A small hand-colored period photograph of The Railway of 1873–74 demonstrated more the actual painting’s absence than Manet’s interest in reproductive media. These gaps could perhaps be overlooked given the treacherous landscape of twenty-first-century museum loans. I do not want to belabor them—plentiful as they were—only in as much as they point to a show seemingly too quickly assembled, selected more from what was available than what made sense.

The bigger question remained the following: did the subdivisions, showcasing the great moments, live up to the show’s promise to offer us some new (why else go to the effort?) insights into Manet, “inventeur du moderne,” into “the man who invented modernity”? A grand claim about the painter’s historical priority and centrality was repeatedly offered by Guégan in both the wall texts and the catalogue: “This exhibition likewise rethinks the multiple links that the painter resolutely established and dissolved with the public and political spheres of his time.”[4] All the more reason to know exactly—and to know exactly how to demonstrate in frames and vitrines—what comprised modernity and a “public sphere” in Manet’s time, and what it might be, precisely, that Manet can be said to have “invented.”

It is largely on this central promise that the exhibition failed, both in its physical and conceptual structure. The exhibition space itself hindered viewers’ deeper understanding of which “modernity” the museum might have had in mind: the show was labyrinthine and dark; small section followed small section; there were odd roped off passageways; some wonderful, rather large paintings like the Portrait of Monet in his Studio Boat of 1874 hung in a small side corridor and we had to look at them as if standing in an elevator; the central section about Mallarmé was tucked away in a tiny corner room; the stark wall colors were distracting in part because they blurred the section headings; the exhibition was far too full of visitors who had nowhere to go but forge ahead and leave quickly; and everything was hung strangely low as if arranged for school visits only. These material constraints simply stopped any 'Aha’ moment immediately in its track. There was barely enough room to look and certainly not enough to ponder.

Such physical limitations were compounded by an array of conceptual flaws. The exhibit was largely arranged chronologically except for the political works like The Execution of Maximilian, which were placed at the very end (after the late still-lifes), seemingly more as an afterthought of a career than one of its central premises. The aforementioned confusion of “story” and “history” did not exactly help to present Manet’s politics seriously. The few comparisons sprinkled throughout—with Legros, Mary Cassatt, or Henri Gervex—seemed utterly random and their meanings were never fully played out or explained. Then there was the strange beginning, all those Coutures and the Homage to Delacroix which nonchalantly led to the Italian period and the section on Baudelaire. “I can’t recall a major retrospective more clumsily devised. It’s a loveless exercise in curatorial pedantry, occupying a maze of cramped galleries larded with works by second-rank figures like Constantin Guys, Alphonse Legros, Govanni Boldini and Berthe Morisot,” was Michael Kimmelman’s acid verdict, and he was not entirely wrong even if “second-rank” is not how I would characterize the achievements of Manet's contemporaries.[5]

These juxtapositions and comparisons might perhaps have offered a fresh look at Manet and the turns in his career, his influences at the time and his obsessions with new media. For once Olympia did not stand as Manet’s defining scandalous achievement. But such unexpected contextualization, welcome as it was at times, also had drawbacks: the Déjeuner now became less “épater le bourgeois” than an almost normalized 1860s old-masterful painting. The same was true for Olympia whose scandal got short shrift in part because sex, peepholes, and prostitution did not square with the exhibition’s highly delimited purview of the modern. Instead, The Amazon arrived on the catalogue cover and The Balcony at its physical and conceptual center. When the visitor left the exhibition, the impressions that stuck—this reviewer ventures to guess—were that Manet’s scandalousness was overrated and that the modernity he favored can be summed up with an ironic treatment of past art in thrall to a new age of image duplication, flavored with some harmlessly fashionable leisure pursuits. This did not square at all with the issues Parisian modernity has come to signify over the past thirty to forty years of exhibitions and scholarship: the nastiness of Haussmannization; class conflict; the fast expansion of capital; the political volatility of the 1860s and 1870s; the Second Empire’s firm grip on its citizens; the domination of the feminine; the ruthlessness of the new image markets and their ever more detailed “techniques” of observation and control. All this was there, of course, visible in Manet’s art—in Olympia’s stare, in all those images and objects in the Portrait of Zola (1868), in the ineffectiveness of his “political” art, in the careful composure of all of Manet’s sitters, and the frequent appearance of a world in which both the newest commodities rule and the simplest things suffice.

But these features were hardly emblematic of the exhibition’s modernity, which failed to engage such fundamental issues, but once more beat up, if incoherently, on the modernist orthodoxy of the primacy of form that dominated early twentieth-century Manet studies: “A regular exhibitor at the Salon, no matter what, the Delacroix of the “new painting” would have only one enemy, the old established concepts of form and the trivialisation of the senses [sic; entrance wall text in English].” I count at least two enemies in that sentence alone, not including the grammar. Easy thing to dismiss modernism once more rather than to take on the tough issues at hand that were promised in the show’s title—“the modern” and modernity. Instead, we got etymological worries over semantic ones: “Modernity. … It now means no more than a vague, lazy desire for novelty. … We therefore prefer to this demonetized word the term “Modern,” the substantivized adjective, capitalized following Mallarmé’s usage in 1874…”[6] But the attempts the organizers made toward actually describing such a newly defined attitude of “the Modern” more often than not ended up sounding like journalistic sound bites and press office quips than anything resembling new scholarship and ideas about the actual—material, ideological, temporal—pressures modernity exerted on Manet’s art. Here again are some of the ridiculous section headings of the show that I hope have already given readers pause: “A Suspicious Catholicism;” “Impressionism Caught in a Trap;” “Less is More?;” “The End of the Story.” (Let me exempt the interesting contributions to the catalogue by Nancy Locke on the image of “consciousness” in Manet and Helen Burnham on Manet’s late pastel portraits.)

My central concern is this: Here was an exhibit that simply deflected both the seriousness of its central problem (for twenty-first-century viewers who still live with, and through, the consequences of much nineteenth-century modernization) and the difficulty and power of its art into quick puns. It favored the essayistic and impressionistic over the scholarly and specific, and only gestured toward context. In this regard, the 2011 Manet retrospective compared unfavorably to Françoise Cachin’s 1983 predecessor, with which it could not compete (even to a viewer like me who was too young to see it). The result was quite disturbing: an exhibit that offered little in terms of new discoveries and concrete arguments, and whose weaknesses swamped the power of one of the nineteenth century’s greatest painters. Apparently, with all that hard cash flowing in, the temptation was just too great to make Manet coextensive with his most palatable profile.

André Dombrowski

Assistant Professor

University of Pennsylvania, Department of the History of Art

adom[at]sas.upenn.edu

[1] The following thoughts are based on an engaging group discussion about the exhibition, organized by Pamela Warner and AHNCA, at INHA in Paris on June 22, 2011. I thank Pamela in particular for her efforts, and also my two co-discussants, Frédérique Desbuissons and James Rubin, as well as all participants of the workshop, for their highly insightful suggestions.

[2]http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/espace-professionnels/professionals/press/press-releases.html, accessed 9/24/2011.

[3] Françoise Cachin, ed., Manet, 1832–1883, exh. cat. (Paris: Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais; New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1983).

[4] “Cette exposition repense de même les multiples liens que le peintre a résolument noués ou dénoués avec la sphère publique et politique,” http://www.musee-orsay.fr/index.php?id=649&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=27127&no_cache=1, accessed 8/24/2011.

[5] Michael Kimmelman, “A Rendezvous with Manet in Paris,” The New York Times, May 17, 2011.

[6] Stéphane Guégan, “Modernism, Modernity, Modern,” in Manet: The Man Who Invented Modernity, 20.