The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Dutch Utopia: American Artists in Holland, 1880-1914

Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia, October 1 2009–January 10, 2010

Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, February 5–May 2, 2010

Grand Rapids Art Museum, Grand Rapids, Michigan, May 21–August 15, 2010

Singer Museum, Laren, The Netherlands, September 16, 2010–January 16, 2011

Dutch Utopia. American Artists in Holland, 1880-1914.

Edited by Annette Stott, with contributions by Holly Koons McCullough, Nina Lübbren, Emke Raassen-Kruimel and Kim Sajet.

Savannah, Georgia: Telfair Books., 2009.

255 pp.; 9 b/w illustrations; 116 color illustrations; bibliography; index.

English edition: $59.95 (cloth)

ISBN: 9780933075115

Dutch edition: €29,50 (paperback)

ISBN: 9789068685480

This winter, the Dutch public had the extraordinary opportunity to experience an unprecedented set of exhibitions dedicated to nineteenth century realist art. The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam housed the overwhelming Illusion of Reality exhibition, curated by Gabriel Weisberg, whereas a somewhat less ambitious exhibition was on view at the Singer Museum in Laren near Amsterdam: Dutch Utopia, American Artists in Holland 1880–1914. The idea for the show originated in the groundbreaking study by Annette Stott, Holland Mania.[1] Holly Koons McCullough, curator at the Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia was inspired by her work with the Telfair's permanent collection to explore the feasibility of an exhibition on the American artists that visited Holland around 1900. She teamed up with Kim Sajet, then vice director of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts who had also been inspired by Stott's study; Sajet then contacted Ineke Middag, director of the Singer Museum, Laren. Together with Holly Koons McCullough as its leading curator, they organised the travelling exhibition Dutch Utopia.

The curators of the show deserve our gratitude for bringing together a collection of more than seventy paintings by artists, the majority of whom were virtually unknown in the country that inspired them. The names of the big stars of the show such as Gari Melchers, George Hitchcock, William Merrit Chase and Walter MacEwen may have some resonance in Holland, but the marvellously observed Municipal Print Shop, 1884 by Charles Frederick Ulrich was a delightful surprise, to this reviewer at least (fig. 1). It is a Norman Rockwell painting without the unsuppressible urge to be humorous in order to please his public. The painting was made during the artist's stay in Haarlem, and shows a room in the printing house of Enschedé & Sons. They were the printer of the Oprechte Haerlemse Courant, the oldest newspaper in the world; according to some accounts, it has been published since 1656. Moreover, Haarlem prided itself for having had among its citizenry, Laurens Jansz. Coster (ca. 1370–1440) the presumed inventor of moveable type.[2] Freedom of the press was, naturally, one of the prerequisites of democracy, and the studio hand seems to drink in this notion, even at his tender age. The very sobriety of the painting with its minute attention to detail seems to reflect the moral value of handwork that has been executed here for hundreds of years. It is an unembellished homage of an American painter to values shared between the two nations.

In all, the big names accounted for about one-third of the exhibition, with Melchers being best represented with nine works, among them his early masterpiece The Sermon from 1886 (fig 8). Chase, on the other hand, is represented with only three works, although his stay at the Dutch coast during the summer of 1884 is arguably a stylistic turning point in his career. Less well known artists make up the remaining two-thirds of the exhibited works, mostly figure and genre paintings that underscore the exhibition's programmatic title. The curators emphasized not only images of Holland by American artists, but also the 'Dutchness', or 'image' of Holland in American culture of the late nineteenth century as reflected in the works of artists that visited the country.

The installation of the show in the Singer Museum, Laren was rather stark, but laid out with clarity. The curator, outgoing director Emke Raassen-Kruimel, had the excellent idea to confront her visitors immediately with the breathtaking panoramic canvas by George Hitchcock, Maternité of 1889 (figs. 2, 3). The Pre-Raphaelite like search for symbolism in reality, as exemplified in the circular fishnet-halo that the young mother carries in her basket, may be slightly obvious, but its all-pervading silvery blue atmosphere is certainly not. Hitchcock was quite sure that this blueness of natural light was a typical Dutch phenomenon.

The rooms were grouped thematically, though not in too rigorous a fashion. Behind Hitchcock's masterpiece, there was a room devoted to the influence of the Dutch seventeenth century art that was one of the magnets for American painters. In addition to loosely brushed portraits in the manner of Frans Hals by Robert Henri, Walter MacEwen's The Notary offered viewers a translation of a Dutch seventeenth century motif crossbred from Gerard Terborch and Pieter de Hooch into a nineteenth century vernacular (fig. 4). To bring his point home, the artist painted the date "1641" as embroidery on the tablecloth. Apparently, the married woman is signing a contract, a remarkable phenomenon because in seventeenth century Holland, married women were officially under guardianship of their husbands; the exception would have been if the husband tacitly recognized his wife's capacity as a merchant woman, which was quite often the case.[3]The Notary can thus be seen as a manifesto of the independent position of women in seventeenth century Holland and a precursor of the liberty that befell women in the United States, a point missed by the all-female team of curators who rightly included gender problems in their approach. Seascapes by William Stanley Haseltine and Dwight William Tryon must provide the link with seventeenth century Dutch marine painters. Whereas Tryon's Meuse River near Dordrecht (1881) successfully provides a Van Goyen-like atmosphere, Haseltine's Dutch Coast (1885), owes more to the contemporary marine painter H.W. Mesdag than to any master of the Dutch Golden Age.

In the first room one is already struck by the very complexity of clearly defining the connections between American painters and Holland in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Other rooms were devoted to the relationship of American painters with the Hague School; the foundations of the American idea of 'Dutchness'; artist's colonies in Holland; the parallels in the national identities of both nations; and the role of anti-modern "Dutchness" in America's Progressive era. The complexity and the degree of abstractness of the set of historical problems that the curators have posed themselves reveals itself in the exhibition as well as in its catalogue. The structure of the catalogue and the titles of the essays make this ambition manifest. The leading author of the catalogue Dutch Utopia. American Artists in Holland 1880–1914 is Annette Stott. She wrote the Introduction and an essay on the 'Egmond School' of American impressionists. The other essays are by Emke Raassen-Kruimel on American artists in a Dutch context; Kim Sajet on American political implications of the Utopian view of Holland; Nina Lübbren, on the narrative function of rural and genre painting; Holly Koons McCullough on the image of Holland in the works of Walter MacEwen.

In her introductory essay, Annette Stott expands the theoretical starting point of the exhibition. As if it were not complicated enough to focus on the American admiration for seventeenth century Dutch art, the catalogue also covers a plethora of thematic essays including the international reputation of the Dutch Hague School painters; the projection of a primitivist, anti-modernist dream upon still mainly rural Dutch society; the perception of parallel traits in the political history of the Dutch and American republics, and the ensuing similarities in national identity; and the emergence of artists' colonies in Holland. In addition, the curator also wished to introduce a discussion of gender by highlighting the professional life of Dutch women. As could be expected, the essays in the catalogue are a storehouse of ideas, some more convincing than others, rather than the rounded vision of a complex set of events and their relationship with a particular range of works of art. The catalogue entries are, on the other hand, quite traditional, being grouped alphabetically and with biographies of the artists integrated in the first entry devoted to them. Such a traditional approach to the catalogue entries makes it sometimes hard to understand why a specific painting is included, especially when its quality does not justify inclusion in its own right; Broken Mast by Mathias J. Alten, for example, tries to impress the viewer with a garish version of the kind of motif that was immortalized in such subtle ways by Jacob Maris, H.W. Mesdag and J.H. Weissenbruch. Lofty statements in the entry about man's dependency on almighty Nature fail to do that job.

In contrast, the essay by Emke Raassen-Kruimel provides a well-balanced introduction to The Hague School and the gradual shift to Laren as a specific locale for painters. Ironically, it was the relative unspoiled nature of Laren, its inhabitants and its surrounding woods and heaths that made painters like Josef Israels, Anton Mauve and Albert Neuhuys move there as soon as it could be reached by rail. Shipments of their paintings could be easily transported by train to The Hague, one of the centers of the international art trade.

In a daring essay, Kim Sajet tries to link the fascination of many Americans for all things Dutch with contemporary political issues in American social politics. "Providing solace in the age of discontent" is her title, and she convincingly argues that many American painters sought to hold up the supposed simplicity of Dutch rural society and its morals to an American public that was in danger of being degraded and abused by life in big cities. In the Progressive Era at turn-of-the-century, Americans were looking for an unspoilt society with values they could share. The Holland they dreamt of presented itself as a closely-knit society, inhabited with blond peasants and fishermen with Protestant morals. A quip often misattributed to Heinrich Heine says that he wanted to move to Holland if he knew the end of the world was near, since everything tends to happen there fifty years later. Of course, this had become a vast exaggeration by the early 1870's with the opening of waterways connecting Amsterdam and Rotterdam directly to the sea, followed by a rapid expansion of the Rotterdam harbor to become the main port of Europe. It should be noted that the attitude of American artists in this respect did not differ from their Dutch counterparts, who founded artistic colonies in their own countryside from the 1860's onwards. The quest for unspoilt purity was a romantic notion shared by the English Arts and Crafts movement and, already in the 1830's, by the Barbizon painters.

Nina Lübbren exercises her close reading skills on rural genre pieces, in particular on Return from Work by Walter MacEwen, shown at the Paris Salon of 1886 (fig. 5). Not without some hesitation, she arrives at the point where the modest anecdote of the painting becomes apparent. A girl has stayed behind and bends over to fasten her stocking while she gazes back over her shoulder at a young man in order to verify whether her ploy has the desired effect. It is here that we feel the need of control by a quote from a contemporary Salon critic to get in touch with contemporary morals. Showing an ankle was no mean feat in the 1880's (Honi soit qui mal y pense). There was actually a lively discussion among Hague School painters about whether narrative elements were acceptable in modern painting. Even the detached observer of nature, Anton Mauve, to whom MacEwen is clearly indebted in this painting, sometimes indulged in the inclusion of a discreet anecdote in his moody landscapes. The subject Nina Lübbren touches upon is one that would be well worth investigating in a wider context.

Is there a unifying element among the American painters that visited Holland? Annette Stott thinks the concept of a "school" applies to the American painters that spent one or more seasons in the Dutch coastal village of Egmond. A lot of local documentary research about this "Egmond School" has also been done by Dr. Peter J.H. van den Berg in his two books on American painters in Egmond, but Annette Stott has only been able to include some of the findings he communicated with her in a note.[4] George Hitchcock prided himself in having "discovered" Egmond in 1881. He even had a house built there, where he and his wife Henrietta were soon joined by Gari Melchers. They became regular inhabitants of the village, but with its transformation into a resort due to the growing popularity of sea bathing as a health improving activity, coastal Egmond lost its charm for them, and they moved a few miles inward to Egmond aan de Hoef.

It is here that I would like to introduce the question of whether one should not first "follow the money" to be able to gauge the validity of the designation "school" to the pupils of Hitchcock and Melchers in Egmond. In the nineteenth century, the term "school" had developed from the designation of a group of artists that had the same master, or that lived in the location, into a generic name for artists that were supposed to share the same artistic principles. Sometimes, this designation evolved into a brand name. The term "Barbizon School" for the generation of landscape artists of 1830 that spent some time in the woods of Fontainebleau, but not necessarily at the same time or with the same artistic convictions, was coined only in 1890 by David Croal Thomson, and it clearly served a commercial purpose. The designation "Hague School" was already used in 1875 during the heyday of its existence. It has frequently been contested because of the diverging artistic production of its members, but it still holds. The "Hague School" as a notion cannot be detached from the blooming art trade in The Hague, notably that of Goupil et Cie. The international commercial success of these painters was highlighted by Charles Dumas, Chris Stolwijk and Dieuwertje Deckers in previous exhibitions and publications, but that phenomenon has been somewhat neglected in this catalogue.[5] It should not be ruled out many American painters flocking to Holland may have hoped to emulate the international success of some Hague painters. Hitchcock, for one, specialized during his first Egmond years in beach scenes in the style of H.W. Mesdag, who had won a gold medal at the Paris Salon of 1870 with a seascape. It was only after Claude Monet had visited Holland in the spring of 1886 to paint the bulb fields in bloom, which he then exhibited rather successfully at the gallery of Georges Petit, that Hitchcock endeavoured to paint the same subject, albeit with a far more moderate palette. Perhaps Hitchcock realized that Monet had only twelve days to spend in the bulb fields, whereas he lived right next to them. His painting, La culture des tulips, was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1887 and was sold immediately.

Annette Stott is quite positive about the notion of an "Egmond School" of painting and she even perceives an "Egmond style". One of the prerequisites for a "school" seems to be that there is at least a group of painters of comparable talent who find common artistic aims or shared ideals by working and living together in close proximity. In the case of Egmond, there are the towering figures of Melchers and Hitchcock who ran their Art Summer School to cater to a mostly well-to-do American clientele. Most of them were women that must have had the opportunity and the means to travel to Europe and devote themselves to painting. Only a few of them subsequently had a professional career as a painter. Tacitly, the selection of the artists for this exhibition betrays this state of affairs. Although many "Egmond School" painters are mentioned, only a few of them were considered worthy of being exhibited here, such as Letta Crapo Smith. Her large painting The First Birthday shows an Egmond mother with her child sitting in the sun in rather garish colors (fig. 6). During her lifetime, Crapo Smith did not succeed in selling the canvas. Its subject is clearly derived from a stock motif from the 1870s by the internationally famous Hague School painter Bernard Blommers. Just for the record, and to show the real proportions in the art world around the turn of the century: in 1904, Blommers, who belonged to the class of internationally successful painters, made a trip to the United States where he was received by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Happily, the strict division of the exhibition into sections was abandoned for a whole room that was practically devoted to Gari Melchers (figs. 7, 8). It was in the Church of the Third Egmond, Egmond-Binnen, that Melchers painted his masterpiece for the Salon of 1886, The Sermon.[6] The catalogue entry cites Jules Bastien-Lepage as the main source for this painting, but I would like to suggest that the subject of this painting and its hyper-realist rendering, were inspired by Wilhelm Leibl's notorious realist masterwork Drei Frauen in der Kirche (1881). Although Melcher's Sermon has always been seen as a mild anecdote of a young girl who has fallen asleep during a sermon, it might be a far more poignant narrative. All churchgoers are absorbed by the sermon, while a young girl, much paler than the other attendants, bends her head while her hands lie open on her lap. A similar motif had been chosen by Hubert Herkomer in his Sunday at Chelsea Hospital that had appeared as a wood engraving in The Graphic of 18 February 1871 (fig. 9). An old soldier has died sitting in his chair during a sermon and his neighbour grabs his arm to wake him—without success. The girl in Melchers' painting has a livid complexion; she is the only one who has lain off her pélérine, perhaps because of a fever. Her paralysed hands have the same emotive impact as those of the old soldier's. The elderly lady next to the girl is neither smiling nor reproaching, but simply concerned what is happening with her. Is seems a soul has gone over to the hereafter during the sermon. A pious life prepares us for the end which is always imminent, seems to be the appropriate message of the painting.

The other works of Melchers are well chosen to present an overview of his career, almost a small exhibition within the exhibition. These paintings show an astonishing variety of styles that testify to the virtuosity of the artist. When his Salon painting of 1887, In Holland was criticized, he simply changed it by adding a few typically Dutch props as a windmill (figs. 10, 11). Next year, he took his revenge at the Salon of 1888 with his impressive masterwork The Pilots (1887–78) that is reminiscent of James Tissot's notorious Prodigal Son in Modern Life series. Melchers preference for astonishing color harmonies, or rather risqué disharmonies, could produce Skaters (ca. 1892) or the almost Nabi-like The Sisters (ca. 1895), and finally the fully fledged impressionist Unpretentious Garden, painted somewhere between 1903 and 1915 in Egmond aan de Hoef.

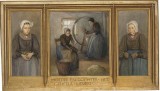

One of the most curious works at the exhibition is a triptych of watercolor drawings by Marcia Oakes Woodbury. She painted Moeder en dochter. Het geheele leven in Laren in 1894 (fig. 12). The left wing shows a young Laren woman who is holding a Bible, her mother on the right wing clutches a rosary. Laren traditionally was a predominantly Catholic village. The watercolor in the middle shows a Laren interior with mother and daughter at work. In the foreground the daughter is carding wool, whereas her mother turns the spinning wheel in the background and winds the thread on a spindle. Textile labor was in fact a cottage industry for farmers during winter, when there was little work in the fields. This is where the Realist reading of the triptych ends. The title, translatable as "Mother and daughter, The Whole Life" is incised in the gilt, medievalising frame. It indicates that labor is the main stuff their lives are made of, but it is also lifting this devotion to labor to another level. Mother and daughter are the Fates spinning their own life's thread, until they enter another life, for which they prepare themselves in a devout manner, by praying and reading the Bible. By choosing the triptych format with its religious connotations, Oakes Woodbury sanctified their daily life.

One can measure the efforts of the catalogue team and, by implication, of the organisers of the exhibition, by comparing it to previous presentations of American artists in Holland. Annette Stott broke new ground in 1998 with her Holland Mania; by that time, Hans Kraan had been working for many years on his encyclopaedic volume Dromen van Holland (Dreaming about Holland) that appeared only in 2002, due to circumstances beyond his control. The analyses of this catalogue team of what "Dutchness" meant for the Americans supersedes all previous efforts in ambition and scope. It is an important contribution to art history as well as cultural history of both countries concerned. As a whole, the catalogue somewhat overshoots its ambition. In their eagerness to paint a grand picture of the American view of Holland, the authors somewhat neglected the social and economic conditions of the art world and the economic realities the artists had to deal with: a social history of art without the most down-to-earth social history.

The quality of the selection for exhibition was generally high, and the casual weakness was unavoidable. It was an unprecedented opportunity to view some of the best American artists of the nineteenth century. Still, one missing link was clearly felt. If there was one American who was not eager to please the demand for typical "Dutchness" it was James Abott McNeill Whistler. He was so fond of Amsterdam that he visited it several times. In his etchings, some paintings and watercolors, Whistler displayed a preference for the more dreary picturesque side of the town that he equalled to Venice. For Dutch artists of a younger generation, such as Georg Hendrik Breitner and Willem Witsen, these were the best work they ever saw of his, and they were greatly influenced by it. It would have been enlightening to have some Dutch work of Whistler included in the exhibition, if only to show that a view on Holland that did not cater to accepted notions or sentiments was possible to an artist with a really independent mind.

Fred Leeman

Art Historian

fredleeman[at]gmail.com

[1] Annette Stott, Holland Mania: The Unknown Dutch period in American Art and Culture (Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press, 1998).

[2] Even in 1884, this claim was no longer taken seriously. The catalogue errs in dating Coster's presumed invention of moveable type in the seventeenth century. See Annette Stott, ed., Dutch Utopia. American Artists in Holland, 1880–1914 (Savannah, Georgia: Telfair Books, 2009), 238.

[3] In Holland, married women would get the right to independently sign a legal document only in 1956.

[4] Peter J.H. van den Berg, The Art Summer School Egmond: 1890-1905 (Egmond: Bahlmond Publishers 2010); Idem, De uitdaging van het licht: George Hitchcock (1850-1913) (Egmond: Bahlmond Publishers, 2008).

[5] Charles Dumas, "Art Dealers and Collectors" in: exh. cat. The Hague School. Dutch Masters of the 19th century (Paris: Grand Palais, and London: Royal Academy of Arts, and The Hague: Haags Gemeentemuseum, 1983); Chris Stolwijk, Uit de Schilderswereld (Leiden: Primavera Press, 1998); Dieuwertje Dekkers, "Where are the Dutchmen? Promoting The Hague School in America. 1875-1900", Simiolus 24 (1996), 54-73.

[6] For some reason, it was exhibited at the 1886 Salon as La prêche à Stockholm – Sermon à Stockholm.