The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Dalou in England: Portraits of Womanhood, 1871–1879

Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut

11 June – 23 August 2009

Dalou in England: Portraits of Womanhood, 1871–1879 Contributions from Cassandra Albinson and Jo Briggs.

New Haven: Yale Center for British Art

Brochure, 19 pp. with B&W illustrations

Cost: Free

This past summer I did not want to miss the rare opportunity of seeing an exhibition focused on a group of small sculptures by Aimé-Jules Dalou (1838–1902) in the United States. Presented at the Yale Center for British Art, the exhibition Dalou in England: Portraits of Womanhood, 1871–1879 focused on five small sculptures by the artist, and was curated by Cassandra Albinson, Associate Curator of Paintings and Sculpture at the Center (fig. 1). A related display of works on paper was curated by Jo Briggs, Postdoctoral Research Associate at the Center. The sculpture exhibition originated at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds where Albinson curated a similar show (entitled Dalou in Britain) of four artworks. Due to the usual problems associated with sculpture exhibitions, related to fragility concerns and transportation costs, two of the sculptures that were included at the Leeds venue were not presented in New Haven: The Reader (1877, terracotta, Manchester City Art Galleries) and Hush-a-Bye Baby (c. 1874, terracotta, Victoria and Albert Museum). They were replaced with comparable works discussed below. At Yale, three galleries were devoted to the exhibition, with five small-scale sculptures by Dalou in various media in the center gallery, and the adjoining two galleries containing engravings, books, other works on paper and one painting, by other artists living in England. Although the literature for the show identified the two rooms of works on paper as "the complementary display," the three galleries were in fact presented as a whole, both physically and in the accompanying brochure, and it would be difficult not to treat them as a unified whole.

An exhibition of Dalou's sculpture has been long overdue in this country and it was insightful of Albinson to present it at Yale. If it were not for the towering presence of Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) in the art historical canon, Jules Dalou would certainly be better remembered today. Although his academic training and style may have been off-putting to modernist scholars, a better understanding of Dalou's political leanings, his period of exile, and his status as an admired teacher in England might have made him a more prominent artist. While Dalou and Rodin befriended each other at the Petite École in the early 1850s, the former followed a more academic path, continuing his studies at the "Grande École," (better known as the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts), an institution to which the latter failed to gain entry. At Yale, except for the first line of the first tombstone that the visitor encountered, which noted that Dalou and Rodin were contemporaries, the latter artist was refreshingly omitted. Dalou really does not need the connection to Rodin to justify his existence or his work. Whereas Rodin concentrated more distinctly in his mature career on literary and mythological themes later associated with Symbolism, Dalou stayed true to his left-wing, republican leanings, focusing on social themes, portraits of people who shared his political viewpoints, and representations of the working class and the poor in sculptures that could be more closely aligned with Realism and with the work of Gustave Courbet (1819–1877), his artistic counterpart in political inclinations.

During the Commune, Dalou was a member of the Federation of Artists, headed by Courbet. Dalou was also appointed, on 16 May 1871, as one of the curators in charge of protecting objects at the Musée du Louvre; he only held the post for seven days.[1] During the famous la Semaine sanglante (the Bloody Week, 22-28 May 1871), altercations between the provisional government of France and the Communards culminated in Paris. While the burnings of public buildings raged there, Dalou escaped the city with his wife, Irma Vuillier (1848–1900), and their daughter Georgette (1867–1915) to England, where they would remain in self-imposed exile for eight years. During that time he was a frequent exhibitor at the Royal Academy exhibitions and would eventually become a respected teacher in South Kensington. In 1873, a military tribunal of the newly established Third Republic government sentenced Dalou, in absentia, to hard labor for life. He did not return to France until 1879, when the Communards were given amnesty.

Dalou in England: Portraits of Womanhood, 1871–1879 opened with a display of artworks by other continental artists who lived in England before him, either as émigrés or as long-term visitors (fig. 2). This gallery contained prints, books, booklets and one painting (figs. 3 and 4) and featured artists including the Swiss painter Jacques-Laurent Agasse (1767–1849), the German-born painter and etcher Philippe Mercier (1689 or 1691–1760), and French artists Gustave Doré (1832–1883), Guillaume Sulpice Chevalier, known as Paul Gavarni (1804–1866), and Théodore Géricault (1791–1824). Unlike Dalou, however, none of these artists were in England as political exiles.

In this display there were some very splendid examples of works on paper that demonstrated Yale's extraordinary print and book collection. Highlights included Géricault's lithograph, Lion Devouring a Horse (1821), which recalls the animalier work of George Stubbs (1724–1806), an appropriate connection to make here, and three additional plates from his series Various Subjects Drawn from Life and in Stone (1821), illustrating everyday life in London. The inclusion in this gallery of Agasse's Studies of Flowers (1848) speaks to England's great admiration for gardens and gardening (fig. 4). It was recently restored at Yale's paintings conservation department and it gleams to superb effect, a welcome addition to an otherwise neutrally colored exhibition of white, black, beige and earth tones. Some of the hand-colored illustrations in books in the display case added color to the exhibition as well (fig. 5). Agasse spent over forty years in England and Studies of Flowers is an excellent example of the naturalist studies for which he was best known.

The major strength of this exhibition, however, was in its exploration of the theme of womanhood, best illustrated in the first gallery by the prints of Paul Gavarni. Four lithographs from his series Les Anglais chez eux (The English at Home, 1852–53) were presented, but the companion prints, Le Baby, dans Grosvenor-Square (The Baby, in Grosvenor-Square) and Le Baby, dans Saint-Giles (The Baby, in Saint-Giles) made for a wonderful contrast (fig. 6). Although humorous, these two lithographs are quite telling of maternal behaviors, heredity and child development, issues that would eventually consume nineteenth- and twentieth-century culture and politics. The baby raised in Grosvenor Square, with its floppy hat and well-dressed caregiver, will most certainly live a pampered existence, while the baby raised in Saint-Giles will probably continue his or her existence in a life of squalor. The Saint-Giles mother, who sits on a pile of rags and smokes a pipe while breast feeding, is enough to make the most unsentimental person cringe (fig. 7). These two lithographs seem most closely associated with the social concerns Dalou examined in his own work: the issues of wealth and poverty, leisure and labor, and the apparent paradox of their coexistence.

The exhibition of Dalou's sculptures of women formally began in the second gallery (fig. 8). In clockwise order around the space, the five technically masterful sculptures displayed were: Young Mother Teaching her Child to Read (also called La Lecture, 1874, terracotta, Musée de Picardie, Amiens, on deposit from the Musée d'Orsay, fig. 9); Maternal Joy (1872, manufactured 1912, Sèvres porcelain, Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, fig. 10); Portrait of the Honorable Mrs. George Howard, later Countess of Carlisle (1872, this cast circa 1907, bronze, Castle Howard Collection, fig. 11); Maternity (Paysanne française, after 1873, terracotta, Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, fig. 12) and Woman Reading (also known as La Liseuse, 1873, terracotta, Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, fig, 13). Staggered around the room with plenty of space between them, each sculpture could be examined individually and viewed fully in the round. These well-chosen sculptures also highlighted the success of translating Dalou's works in a variety of media, from the creamy-looking paste of Sèvres porcelain to the hard, metallic shine of cast bronze (fig. 14). Three of the five sculptures in the exhibition were produced in terracotta, on which Dalou's expressive tool marks are elegantly preserved in the refined clay.

It is interesting to note how devoted Dalou was to the idea and ideals of womanhood; it is a theme that he handled with great care and with attention to physical and emotional detail. More often than not, this is mistaken for saccharine sentimentality. While it is true that Dalou played to his market in England, he did so while still creating serious works. In some cases, Dalou's arrangements are interchangeable, and sometimes a baby can be substituted for a book without too much thought or compositional change (fig. 15). Yet others, as in his breast feeding women, exemplified in this exhibition by Maternal Joy (fig. 10) and Paysanne française (fig. 12), were nascent examples of figures that would appear in larger, later projects such as his Charity Fountain (1877–1879), installed outside of the Royal Exchange in London, and in his unfinished Monument to Labor. The commission for the Charity Fountain was not mentioned in the exhibition or its accompanying literature, which seemed odd because Dalou later became famous for his large public commissions completed in Paris after his return to France, such as his Triumph of the Republic (1889) at the Place de la Nation in Paris. The Charity Fountain was one of Dalou's great, early successes and his most public image of womanhood (albeit in the guise of an allegory) in England. Womanhood, in Dalou's world, is about the giving of one's self to others, and females seem to occupy themselves with two main tasks in his sculptures: reading and being motherly, the latter often (but not always) exemplified by breastfeeding. Certainly both actions relate to the nourishment of the mind (books) and the body (milk). The sculpture Young Mother Teaching her Child to Read joins motherly love with the act of educating one's own children through reading (fig. 9). This sculpture combines a physical and a psychological closeness between the mother and daughter, making us aware of powerful human connections discovered through such common tasks. Maternal Joy does the same (fig. 10). In viewing the commanding mantelpiece-sized version of Maternal Joy, one can only imagine how even more impressive the life-sized version, now lost, had been when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1872. Paysanne française, depicting a Boulogne-region woman wearing a simple garment and farmer's clogs, is of a type that one most associates with Dalou, that is, the glorified peasant (fig. 12). Unlike the other two mothers discussed here, the breastfeeding mother in Paysanne française does not sit on a luxurious piece of furniture, but on an upturned straw basket, similar to Gavarni's smoking peasant in the first gallery, who sits on a pile of rags. Yet, the woman depicted in Paysanne française is no less elegant, no less motherly, than the upper-class women depicted in the other two sculptures. In the peasant's motherly action, she is their equal. As Albinson astutely points out in the exhibition brochure, Dalou "imagined his group of women as domestic, perhaps bound by their class, yet harmoniously coexisting."[2] What binds most women together is not money or class status, or even nationality, but their ability to produce and care for their young; Albinson points out in the brochure that this was a "radical concept" in the 1870s. Without doubt, in a post-Darwin world, biology transcends class.

Also included in the exhibition was Dalou's Portrait of the Honorable Mrs. George Howard, later Countess of Carlisle (fig. 11). This sculpture seems to have been the impetus for the entire show. Albinson's dissertation, Peeresses in Paint: Portraits of Aristocratic Women and the Question of Representation, 1837–1901 (Yale, 2004), was concerned with images of high status women in England, and although she focused on paintings in her doctoral work, Dalou's sculpture of Rosalind Howard piqued her interest during her research. Although Mrs. Howard was no slacker in the motherhood department (she had eleven children), she is instead depicted by Dalou as a fierce intellectual. She was a supporter of women's suffrage and the temperance movement in Britain, and she and her husband George Howard, the 9th Earl of Carlisle had an extensive network of artistic and political contacts.[3] George Howard commissioned a terracotta portrait of his wife from Dalou, which was shown in the Royal Academy exhibition of 1873; only later were versions cast in bronze. In the sculpture on view, Rosalind Howard is dressed in a bohemian outfit with a book open on her lap and arms defiantly crossed; she seems a force to be reckoned with. Though the bronze cast seems flat and lacking in detail when compared with the fresh, highly detailed earthenware works surrounding it, there are few examples of Dalou's English works cast in bronze, and this was a nice addition to the exhibition. It was also appropriate to include a portrait of a woman who seems content with herself and her individual identity without the need of her children or her breast milk to justify her existence.

The star sculpture of the exhibition was without doubt Dalou's Woman Reading (fig. 13). Created in the same year as the statue of Rosalind Howard, it demonstrates even more freedom and individual spirit than the portrait. The terracotta is exquisitely tooled, with every button, stitch and tassel perfectly placed. While one imagines Rosalind Howard reading something serious, such as the speeches of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the young woman's languorous pose, blissful smile and deep engrossment in her book suggests that she's reading something a bit scandalous. (I enjoyed imagining she was reading a novel such as Zola's Thérèse Raquin, or something equally full of sex and murder.) Dalou provided tiny details that give us an idea of the woman's status: a graceful wedding band surrounds a delicate ring finger, and rosettes on her shoes contrast with the farmer's clogs on Paysanne française behind her. If one were looking for Impressionist themes in three-dimensional artworks, Woman Reading would serve as an excellent example. If one were looking for the sculptor of modern life, Dalou and his oeuvre would provide excellent examples.

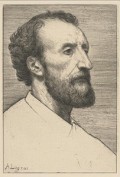

In the final gallery, we returned to works on paper, in particular to prints made by French artists in England during the same period when Dalou was living there (fig. 16). Although there were numerous French artists living in England from the beginning of the Commune and through to the end of the nineteenth century (Claude Monet, Jules Bastien-Lepage, among many others), the final gallery focused on only two artists: Alphonse Legros (1837–1911) and James Tissot (1836–1902). The selection of Legros was appropriate: Dalou and Legros had been friends at the Petite École, and the latter became an invaluable resource for the former. Legros had first visited England in the early 1860s, so he had a better knowledge of the country than did Dalou; he brought Dalou to South Kensington in 1877 to give demonstrations in modeling clay, which led to his being hired at the National Art Training School; and he introduced Dalou to important clients, such as the Howards.[4]

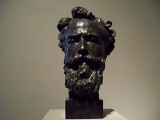

Legros' etched portrait of Dalou from around 1875 is well-known and was exhibited here with an example from Yale's University Art Gallery collection (fig. 17); missing was Dalou's bronze portrait of Legros from around the same period (c. 1876, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC), which might have served as a nice corresponding work (fig. 18). Other works in this gallery by Legros, including an etching entitled The Death of the Vagabond (undated) and a pen and ink drawing entitled In the Skirts of the Forest (1880), were quite fine but seemed to deviate from the more interesting theme of womanhood that was really the heart of the exhibition.

The final prints by Tissot consisted of three etchings and two chromolithographs that the artist produced during his eleven year stay in London (1871–1882). The color prints of a businessman and the Commander-in-Chief in India (both 1876), images Tissot made for Vanity Fair, contributed little to the dialogue of the exhibition. The etchings, however, returned the viewer to the theme of womanhood with scenes of a woman at leisure. The model for these images was Tissot's mistress Kathleen Newton (1854–1882). Her status as a divorced woman with two illegitimate children made her and Tissot the objects of rumors and ridicule, and her death in 1882 from tuberculosis prompted Tissot's return to France. The best of these etchings was Deep in Thought (1880), an excellent example of the age-old female problem of having to choose between a domestic life and a life of learning (fig. 19). With a small child on the woman's right side and an open book on her left, she seems lost, almost despondent, between the two. At the risk of reading too much into this work, I would nonetheless describe the etching as a brilliant summing-up of the conundrum of womanhood, and a perceptive prediction of the angst women would experience in the coming century. Tissot here picked up where Dalou left off and confronted, with this etching, the future of womanhood.

Dalou's years as a teacher in England were not treated in this exhibition, and it seemed a missed opportunity. It may have furthered one's understanding of the success of his English period to showcase his effect on the young students he influenced over his short, two-year stint as a teacher in South Kensington. It may have been educational to include a sculpture or two by one of Dalou's students, such as Alfred Drury (1856–1944). However, I was told that there will soon be an exhibition at the YCBA focusing on Victorian sculpture, covering in part the New Sculpture movement, and that such additions would have made the upcoming exhibition seem repetitive.

These observations, however, are not meant to demean an exhibition that really accomplished a great deal in only three rooms. In short, this was a splendid show. It focused attention on rich, high quality artworks, and the overall presentation was admirable. Although at times the exhibition may have lacked continuity between the print galleries and the central room containing Dalou's works, on the whole there were some very appealing parallels present. It illuminated the artistic lives of French artists in England, two countries that traditionally had a long history of animosity towards each other; it brought to light some important issues of networking, support and patronage; and, most importantly, it explored, mainly through five of the most technically astute and beautiful sculptures to ever be molded under Dalou's skilled hands, the circumstances of womanhood in nineteenth-century Europe. We should remember that this was accomplished by a university museum, one willing to take risks on artists that remain outside of the canon. I cannot think of a nineteenth-century sculptor who deserves to be reexamined more that Jules Dalou; I hope that Dalou in England: Portraits of Womanhood, 1871–1879 will prove to be the first of many reassessments of this artist.

Caterina Y. Pierre, Ph.D.

City University of New York at Kingsborough

caterinapierre[at]yahoo.com and cpierre[at]kingsborough.edu

Related Links:

Official Site for the Association of College and University Art Museums and Galleries:

http://www.acumg.org/index.html

Official Site for the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds:

http://www.henry-moore-fdn.co.uk/

Official Site for the Yale Center for British Art:

http://ycba.yale.edu/index.asp

I wish to express my thanks to Ms. Amy Athey McDonald and Mr. Ricardo Sandoval of the Public Relations and Marketing Department of the Yale Center for British Art, for their helpful assistance with the photography and the checklist for this review, and Dr. Brian Edward Hack, for assisting with some of the exhibition installation photographs.

[1] For information regarding Dalou's role in the Fédération des Artistes, see Gonzalo J. Sánchez, Organizing Independence: The Artists Federation of the Paris Commune and its Legacy, 1871–1889 (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), throughout the text, but especially 81-82, 113-115; and 160-161.

[2] Cassandra Albinson, "Dalou in England, Portraits of Womanhood, 1871–1879," in Dalou in England, Portraits of Womanhood, 1871–1879, Exhibition Brochure (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 2009), 16.

[3] Albinson, 11.

[4] Susan Beattie, The New Sculpture (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1983), 14; and Albinson, 11.