The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

|

|||||

|

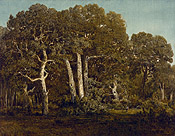

Théodore Rousseau (1812–1867) Forest of Fontainebleau, Cluster of Tall Trees Overlooking the Plain of Clair-Bois at the Edge of Bas-Bréau (c.1849–1855) Oil on canvas, 90 x 116 cm. (35 7/16 x 45 11/16 inches) |

|||||

| The J. Paul Getty Museum recently acquired a large-scale painting by Théodore Rousseau that is rare in quality of execution and condition (fig. 1). Aside from a three-year tour of French paintings from 1939 to 1941 to museums in Central Europe, South America and the United States, the painting has not been seen in public since its presentation at the Cercle des Arts on the rue de Choiseul during Rousseau's 1867 exhibition of études peints (painted studies) in Paris. Forest of Fontainebleau, Cluster of Tall Trees Overlooking the Plain of Clair-Bois at the Edge of Bas-Bréau depicts a corner of Fontainebleau known as Bas-Bréau, near Rousseau's home in the village of Barbizon. An old-growth section of the forest with ancient, towering oaks, Bas-Bréau attracted Rousseau beginning in the winter of 1836–1837, and he continued to paint in this area throughout his career. The Getty painting was assigned in Michel Schulman's 1999 catalogue raisonné the date of 1847, most likely based on the date given in the catalogue of the 1867 Cercle des Arts exhibition (where the painting bears the title Lisière du Bas-Bréau. Haute futaie donnant sur la plaine de Clairbois; large ébauche. Les vaches descendent boire à une flaque d'eau (Edge of Bas-Bréau. Old Growth Trees Facing the Plane of Clairbois; Large Sketch. Cows Descending to Drink at a Pool of Water.) Although Rousseau probably advised those dates, the canvas stamp on the back of the picture bears the name "Debourge," a canvas maker who ran his business in Paris from 1849 to 1855, suggesting that Rousseau may have been working from a somewhat inaccurate memory. Unlined, on its original stretcher and in its original frame, with a surface that seems to be almost entirely intact, it offers an opportunity to experience a pristine example of this particular kind of Rousseau painting, the ébauche or dessin-peint, and to study his technique in developing these large-scale painterly works. | ||||||

| Rousseau was trained in the studio of the academic landscape painter Joseph Rémond, but quickly moved away from a neo-classical aesthetic towards the more empirical, naturalist models of John Constable, (whose paintings were so influential in France after his Salon debut in 1824), and of 17th-century Dutch landscape painters such as Jan van Goyen, Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema. Although he was born in Paris, and kept a fairly firm foothold in the French capital through most of his career, Rousseau devoted himself to recording the French countryside, and in particular the Forest of Fontainebleau. From 1836 on, he summered in Fontainebleau regularly, returning to Paris each winter. In 1847, he bought a house in Barbizon and settled there permanently. His canvases convey a sense of the city man's nostalgia for the timeless, ancient ways of rural life and the constant rhythms of weather and seasons.1 He was particularly taken with what he perceived to be the solidity and stoicism of old trees, and he produced hundreds of tree sketches in oil, pencil and crayon. | ||||||

| Throughout his career, Rousseau sketched outdoors incessantly, and he used a special easel and lean-to to facilitate painting outdoors in the summer. His "finished" paintings, however, were worked up in his studio (back in Paris in the winter, and in his studio in Barbizon after he moved there in 1847). There are very few cases (given the volume of his production) of directly transferred compositions from his outdoor sketches to his paintings.2 Sketching from nature seemed to be less about gathering material for studio paintings than a valued process in its own right, a means of immersing himself in natural sites, a form of active aesthetic meditation. Rousseau's reverence for nature, verging on pantheism, is a central motif in the literature on the artist. In his recent monograph on Rousseau, Greg Thomas developed and historicized this theme. He argues not only that Rousseau was an early environmentalist, but also that he embodied in his practice what Thomas calls an "ecological consciousness," a rising recognition in the nineteenth century that man was not divinely separated from nature, but an animal organically integrated within it, "a manifestation of the very 'nature' we had thought was our opposite."3 Thomas suggests that Rousseau's artistic production was as much if not more about the practice of ecological awareness as it was about creating a saleable, critically acclaimed oeuvre. | ||||||

| The Getty painting may have been started on site, but it was certainly finished in the studio. There is an oil sketch in a private collection that depicts the same site (Schulman 1999, no. 385, where the date is given as 1850 and the dimensions as 30.5 x 48.3cm). In the sketch, the central live oak, the patch of water, and the open plain beyond a screen of four trees are all there, but it lacks the dead oak to the right of the central tree, and the dead oak at the left is only vaguely smudged in. Furthermore, the strokes describing the branches of the live tree are visible through the overlapping dead trunk, all of which suggests that Rousseau added the dead oaks to the Getty painting for their poetic effect, enhancing the composition with their dynamic, jagged shapes. One is reminded that despite the freshness and verisimilitude of Rousseau's landscapes, they are infused, almost always, with a profoundly Romantic temperament. | ||||||

| The expressive effect of the Getty painting is, nevertheless, one of freshness, immediacy, and liveliness. The foreground of earth, boulders, grass and broken branches is barely suggested, and the dramatic focus of the canvas converges on the trunk, branches and foliage of the central live oak, flanked by the two dead trees whose sharp, splintered forms are evoked with quick upward-thrusting strokes. The meandering graphic shapes of the central oak's branches, whose gnarled limbs stretch around one another towards the sky, clearly fascinated the artist. Daylight reflects off the pond and up into the branches, filtering through the foliage in an extraordinarily nuanced range of earthy greens and browns. He sketched in the composition with a thin brown medium, possibly what was called in the nineteenth century momie, over which he layers rich glazes using a variety of brush sizes and textures. He scratches and scrapes paint away to reveal lighter ground layers, as in the milky reflection on the pond, and he selectively applies impasto, mostly on the dead tree at the center. The result is a work of penetrating vitality, vibrating with the rhythmic movements of the brush, held together by a firmly conceived composition. | ||||||

| Seen with adequate levels of natural light, the painting requires prolonged viewing to register the extraordinary range of greens and earth tones in what at first glance seems to be a monochromatic painting. In the conservation studio, with the dirty layer of varnish removed, the painting gains a sense of space, and a kind of humid, breezy atmosphere. The painting does not have the open space of Rousseau's panoramic compositions, or the central clearing of many of his forest scenes. Instead the experience is one of slow, quiet, sensual immersion in the scene. | ||||||

| Barely visible is a single figure and some cows making their ghostly entrance at the right, coming around the bend and into the water. As in most of Rousseau's Salon paintings, these beings serve as a suggestion of animate presence, but they offer no narrative or anecdotal purpose. Rousseau's protagonists are the trees, the ancient oaks and their lively interaction with their environment, as the painter weaves together foliage, branches, bark, grass, rocks, earth, water, and sky. There is an uncontained character to the painting. The composition is centered around the live oak with other trees serving as a framing device at left and right, but the surface texture vibrates with painterly energy, the brushwork rippling and fanning out in multiple directions. After we had studied the painting for weeks out of its frame, it was something of a visual relief to return it to its gilded borders. | ||||||

|

The Cercle des Arts exhibition of 1867 was titled "Notice des études peintes par M. Theodore Rousseau," and indeed the majority of the 109 paintings seem to have been studies from nature, small to medium in scale, presumably on canvas (medium is noted in the catalogue only when the work is on panel). In his introduction to the catalogue, Philippe Burty refers to the paintings on view as "quatre-vingts études peintes et des quelques tableaux" (eighty painted studies and several finished paintings). The Getty painting is described in the catalogue as a large ébauche, one of only three with that designation and of five total with the label ébauche. Very few of the entries in the catalogue are notated with the academic categories of étude, ébauche and tableau, and whether the ébauche assignation was made by Rousseau or Burty or someone else, and precisely what they meant by it, is difficult to determine. Three of the five ébauches are fairly large in scale, including the Getty painting and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston's Great Oaks of Old Bas-Bréau (1864; of the same scale as the Getty painting though not described as large [fig. 2]). Were these paintings, as the contemporary academic definitions would have them, preparatory drafts of more finished tableaux?4 Or are they examples of what Nicholas Green calls dessin-peint or ébauche, a kind of painting initially developed by Rousseau with Jules Dupré in 1844 that Rousseau further developed later in his career, marking a radical break with the distinctions between preparatory and finished work so clearly articulated by Valenciennes in the early 19th century?5 Green defines this new kind of public painting:

Other paintings that may be included in this category are the Mesdag Museum's Chopping Trees on the Ile de Croissy (1847), which was also in the 1867 Cercle des Arts exhibition, the Mesdag's Vieux Chêne à Fontainebleau (1852), the Metropolitan Museum's Soleil couchant sur la lande d'Arbonne (c.1863), the Cleveland Museum of Art's Edge of the Forest at Sunset at Bas-Bréau (c. 1860), and two works recently on the market, Soleil couchant sur les Sables de Jean-du-Paris (c. 1864) acquired by the Wadsworth Atheneum, and La Mare aux fées, forêt de Fontainebleau (c. 1848, private collection). These paintings are the seeming antithesis of Rousseau's smaller, more iconic paintings characterized by their meticulous, careful, highly-labored facture, such as Toledo's Le Curé (1842–1843) and the Frick Collection's Village of Becquigny (1857–1865), tableaux in every sense of the word. And in their grand scale and compositional resolution, the dessins-peints are also distinct from both études (nature studies intended as preparatory work) and what Green calls "dealer pictures," small to medium scale picturesque works intended from their inception for the private market.7 |

|||||

| The unraveling of these academic distinctions, which would come to a such a dramatic head in the early scandal of Impressionism, is a fascinating phenomenon at mid-century, and clearly needs more scholarly attention. Rousseau is the central figure here, but getting a firm hold on his role within and contribution to the history of painting has been elusive. His oeuvre is scattered far and wide, and his experimental practice has resulted not only in confusion and mystery in terms of his technique, but also in so many badly preserved canvases in which pigment, detail and subtle light effects have descended into dark brown and black. The current resurgence of interest in Rousseau and Barbizon painting will, I hope, result in important new findings by art historians and conservators. | ||||||

|

Provenance: The painting was bought from the artist by the dealer Durand-Ruel in either September 1866 with a selection of seventy of Rousseau's works (for the total price of 130,000 francs), or in June 1867, for 2,000 francs. It was bought by a M. Goldschmidt in May 1869 for 4,800 francs. Acquired at some point thereafter by Alfred Feydeau (1823–1891), the painting was sold on May 22, 1902 at the Hotel Drouot sale of Feydeau's collection to the dealer Bernheim Jeune & Fils for 24,000 francs, under the title Les Grands Chênes. The painting was then resold, (according to a bill of sale provided by the seller to the Getty), by Bernheim Jeune & Fils on June 25, 1902 to M. Henry Gallice (1853–1930) of Epernay, for 80,000 francs. The picture was inherited by Henry's daughter, Rosy Gallice, who married André de Chastellus. It then passed by descent in the Chastellus family until its sale to the Getty Museum. |

||||||

|

Publications: L. Roger-Milès, Préface, Collection Alfred Feydeau, Tableaux Modernes, Aquarelles & Dessins, Hotel Drouot, Paris, May 22, 1902, 6, 24–25 (ill.), no.11, as Les Grand Chênes. Michel Schulman, Théodore Rousseau: Catalogue raisonné de l'oeuvre peint (Paris: Editions de l'Amateur – Editions des Catalogues raisonnés, 1999), no.384 (ill.). The provenance in this catalogue is not entirely accurate. |

||||||

|

Exhibition history: Paris, Cercle des Arts, Notice des Études peints par M. Theodore Rousseau, exh. cat. (Paris: L'Académie des Bibliophiles, 1867), no. 58. Belgrade, Musée de Prince Paul, Peintures françaises du XIXe siècle, exh. cat. (Belgrade: Musée de Prince Paul, 1939), no.102 (illustration), as Le Vieux Chêne (Forêt de Fontainebleau). Buenos Aires, Museo National de Bella Artes, La Pintura francesa de David a nuestros dias, exh. cat. (Buenos Aires, Museo National de Bella Artes, 1939), no. 121 (illustration), as El Viejo Roble (bosque de Fontainebleau). Montevideo, Salón Nacional de Bellas Artes, La Pintura Francesa de David a nuestros dias, exh. cat. (Montevideo: Salón Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1940), no. 94 (illustration), as El Viejo Roble (bosque de Fontainebleau). San Francisco, M. H. De Young Museum, The Painting of France since the French Revolution, exh. cat. (San Francisco: The Recorder Printing and Publishing Co., 1940), 64, no. 97 (illustration) as The Old Oak (Forest of Fontainebleau). New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, French Painting from David to Toulouse-Lautrec: Loans from French and American Museums and Collections, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1941), no. 106, as The Old Oak. Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, Masterpieces of French Art Lent by the Museums and Collectors of France (1941), no. 142, plate XVIII. Portland, Portland Art Museum, Masterpieces of French Painting from the French Revolution to the Present Day, exh. cat. (Portland: Portland Art Museum, Oregon, 1941), no. 99, as The Old Oak (Forest of Fontainebleau). Stickers on the back of the painting indicate that on the same 1939–1941 tour, the painting also visited Rio de Janeiro. |

||||||

| Mary G. Morton Associate Curator of Paintings, The J. Paul Getty Museum |

||||||

|

In studying this painting, I am indebted to the observations and analysis of Getty Museum curators and conservators Scott Schaefer, Scott Allan, Mark Leonard, and Yvonne Szafran; Getty conservation scientist Alan Phenix; and colleagues René Boitelle and Simon Kelly. 1. See Nicholas Green, Theodore Rousseau, 1812-1867, exh. cat. (Sainsbury Center for the Visual Arts and Hazlitt, Gooden & Fox, 1982) and Nicholas Green, The Spectacle of Nature: Landscape and Bourgeois Culture in Nineteenth-Century France (Manchester University Press: Manchester and New York, 1990) for a description of Rousseau's work as an extension of the urban Romantic's myth of the forest as pristine, primeval Nature. 2. In his introduction, Schulman lists several instances in which Rousseau transferred the composition of a sketch to a finished work. See Schulman, Théodore Rousseau: Catalogue raisonné, 66. 3. In 1852, Rousseau and his friend and biographer Alfred Sensier submitted a petition to the Emperor through the Duc de Morny, an influential politician close to Napoleon III, protesting the commercial exploitation of the trees and rocks of Bas-Bréau, and requesting its protection. See Greg M. Thomas, "The Practice of >Naturalism< The Working Methods of Théodore Rousseau" in Barbizon: Malerei de Natur – Natur der Malerei (Munich: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1999) and Greg M. Thomas, Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France: The Landscapes of Théodore Rousseau (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.) 4. Quoting from the Académie des Beaux-Arts dictionary of 1858, Albert Boime defines an étude in landscape painting as a small summary work delineating the character of the motif and indicating light effects. The ébauche is more of a technique of laying in a composition in broad, loose strokes, usually a preliminary stage in the creation of a finished work. A tableau is a finished work, worthy of public exhibition at the Salon. See Albert Boime, The Academy and French Painting in the Nineteenth Century, (London and New York: Phaidon, 1971). 5. See Green, Theodore Rousseau, 11-15, and Fred Leeman and Hanna Pennock, Museum Mesdag: Catalogue of Paintings and Drawings (Amsterdam, 1996), 386. 6. Green, Theodore Rousseau, 15. 7. Ibid., 61-62. Green makes the point that later in his life Rousseau relaxed the distinction between private, preparatory work and paintings for public display, compelled as he was to sell less finished paintings. Ibid., 10. |

||||||