The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

John Scott Bradstreet: the Minneapolis Crafthouse and the Decorative Arts Revival in the American Northwest |

|||||

|

When the Minneapolis interior designer John Scott Bradstreet (1845-1914) died in a car accident at the age of sixty-eight, the Minneapolis Journal began its tribute to his life with high praise. "If this section of the country is to furnish a name that will be known to the America of one hundred years from today," the Journal's tribute began, "That name is more likely to be that of John Scott Bradstreet than any other." With shrewd and unfortunately accurate foresight the author of the eulogy continued: "We say 'more likely,' because fame is a thing about which it is impossible to make accurate or even reasonable predictions."1 For nearly forty years Bradstreet, a New Englander by birth, devoted his talents and artistic vision to his adopted city of Minneapolis, a bustling frontier outpost still in the awkward stages of metropolitan adolescence. Working at a time when gaudy Victorianism reigned and industrially manufactured furniture and "art produce"2 were increasingly available to the emerging class of successful settlers, Bradstreet strove from his earliest ventures to offer to the city's residents an artistic alternative. Quickly achieving prominence as an entrepreneur of considerable artistic vision, Bradstreet used his position as a local tastemaker to offer a refined version of artistic eclecticism and to cautiously introduce to the region contemporary styles with which he had become acquainted during his many travels. | |||||

| Once described as "a conscientious student of the art decorative in many lines for many years,"3 Bradstreet developed his style principally by following the trajectory of larger international movements. Initially interested in the 1870's in the modern Gothic style popularized by English Arts and Crafts designers, by the beginning of the 1880's Bradstreet had also enthusiastically embraced the ideals of Whistler and the Aesthetic movement, had fully immersed himself in the contemporary Moorish craze, and had become increasingly interested in the art of Japan. In this formative decade, Bradstreet applied his discriminating tastes to the project of assimilating these contemporary styles for importation back to Minneapolis, while steadily developing his own unique design theories and distinctive style. | ||||||

| The Minneapolis Crafthouse, opened in 1904, marked the culmination of Bradstreet's career as a tastemaker to the city of Minneapolis and contributed substantially to his growing reputation as a significant presence on the American decorative arts scene.4 Its opening attracted attention far beyond the city of Minneapolis and it became celebrated as a haven for the handicrafts, a museum of the decorative arts, and an achievement in the eclectic but refined synthesis of an array of popular styles. In a 1904 review accompanied by photographs of the building and grounds, the widely read International Studio approvingly assessed, "To hit upon the unexpected always adds interest to the investigation of an undertaking; and to find that Minneapolis can boast one of the most striking and 'go-ahead' establishments for the propagation of the crafts came, we must confess, as a surprise to us—and will to many."5 As the International Studio's review suggested, the idealism, sophistication, and artistic progressiveness of the Crafthouse was something of an anomaly, given its location in what was then colloquially called the American Northwest.6 | ||||||

| The Crafthouse embodied both physically and conceptually a synthesis of styles that became known as "the fellowship of good things."7 It represented Bradstreet's belief that the American designer was heir to all that was good from every school of design and that exclusive devotion to the style of any country or period was restrictive and hollow in its purely imitative nature. The eclectic possibilities of this design theory were an ideal counterweight to the inherently Utopian leanings of the Crafthouse and allowed Bradstreet to cater to a broad range of tastes among his patrons. At the same time, he was able to remain true to his desire to create a workshop and showroom aligned theoretically with the major tenets of the English Arts and Crafts movement in its emphasis on the preservation of handicrafts and the creation of an imaginative environment hospitable to the meeting of the arts. Bradstreet's pragmatic approach lent the Utopian venture wide appeal and a degree of financial viability that allowed him room to pursue his more avant-garde ideas and to develop and nurture his most progressive endeavor, the jin-di-sugi style of woodworking. These achievements, upon which the enduring significance of his work rests, were the product of a long and varied career; and Bradstreet's transformation from humble beginnings as an engine turner at Gorham Manufacturing, to a furniture salesman in the pioneer city of Minneapolis, to an interior designer of international repute, serves as the backdrop for his development as a member of the American decorative arts revival. While Bradstreet's contributions to the Arts and Crafts movement in America took many forms, as will be argued here, it was essentially through the organization of the Crafthouse that he was able to present a mature and coherent stylistic approach to interior design reform. | ||||||

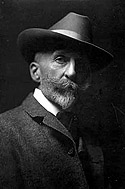

| I. Bradstreet's Early Years John Scott Bradstreet (fig. 1) was a member of one of New England's oldest families and could trace his heritage back to William Bradford, the second governor of Plymouth colony.8 Born on December 14, 1845 in Rowley, Massachusetts, a small town about thirty miles north of Boston, Bradstreet appears to have enjoyed a relatively comfortable upbringing, but as the eldest of four children of a shoe cutter,9 the privileges to which he was exposed must have been somewhat limited. He received his education at Putnam Academy in nearby Newburyport and in December of 1863, shortly before his eighteenth birthday, secured work at Gorham Manufacturing, an important producer of high-end silver wares located in Providence, Rhode Island. Although the date of his graduation from Putnam remains to be established, his employment at Gorham prior to the conclusion of the Civil War suggests that it is unlikely that he saw military service. Starting out at Gorham as an engine turner, within two years he was promoted to the position of salary clerk, eventually becoming the company's supply clerk until his departure in the summer of 1872.10 Bradstreet does not appear to have been involved in any creative capacity during his nine years at Gorham; rather the period was significant for the valuable business and logistical experience he gained working in a large American decorative arts firm and also for the establishment of relations with the Thurber family, co-owners of Gorham, with whom he would later enter into an important business partnership. |

||||||

| In the summer of 1872, Bradstreet left Gorham and resettled in Minneapolis, finding work as a salesman for the furniture firm Barnard, Clark, and Cope.11 Little is known about the circumstances surrounding Bradstreet's decision to venture west. Throughout his life, he was plagued by frail health, and his desire to find a climate better suited to the tuberculosis which he had contracted has been cited as the reason for his decision to move to the drier air of Minnesota.12 When Bradstreet arrived in Minneapolis the city was, as one Minneapolitan later recounted, "little more than a sprawling frontier town."13 Less than twenty-five years old, the city was accelerating through a period of development—railroad, grain, and lumber industries were rapidly being developed and fortunes were briskly accumulating. An emerging retail industry catered to the growing market of successful settlers who wished to flaunt their newly earned wealth and status. In these early years High Victorianism was epidemic and culture and refined taste were rare commodities. One friend of Bradstreet later recounted, "He came into a raw, pioneer community early in its formative stage, when the brutal hideousness of rampant bad taste found expression in crude and glaring examples, both without and within, abhorrent to the trained and cultivated intelligence."14 To the market for professional interior design advice created by this excess of wealth and dearth of taste, Bradstreet's amiable personality and natural artistic temperament were particularly well suited.15 | ||||||

| Bradstreet's inclination toward elegance extended to his personal life as well, and he assiduously cultivated a public persona of a man of breeding and intelligence. He moved to a "private" boarding house16 and was often seen driving about town in his phaeton pulled by a bob-tailed horse. He presented a meticulous image as a fashionable man about town and paragon of good taste. Noted for his dandyish style, he was remembered in these early days for a penchant for dressing in tan suits chosen to compliment his auburn hair, the combination of which he set off by jade cuff links and ties crafted from his finest upholstery samples.17 Bradstreet quickly formed business and personal relationships with Minneapolis's burgeoning middle and upper classes and became enthusiastically involved in the city's emerging cultural scene. Within five years he had successfully prevailed upon his friends to assist him in organizing the city's first loan exhibit of art open to the public. Held in 1878, the interest it roused contributed substantially to the founding of the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts five years later.18 | ||||||

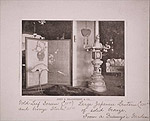

| In 1875, just two years after his arrival to the city, Bradstreet opened his first fine furniture shop, advertising his establishment as a manufacturer of artistic domestic furniture of Modern Gothic and other designs (fig. 2).19 In 1878 Bradstreet formed a friendship and business partnership with Edmund J. Phelps, a young entrepreneur recently arrived from the East.20 An article in the St. Paul Pioneer Press reporting the opening of their elegant new showrooms (fig. 3) described a selection of fashionable items to be found within the novel furniture shop: a Modern Gothic canopied bed draped with rich fabrics of dull Persian blue and Venetian red, furniture and cabinets of rich woods, luxurious velvet hangings, Indian silks, and other exotic items such as "a framework in Queen Anne style with panels and carvings Japanesque," and windows shaded by Japanese scenes, an element which the Press deemed, "both original and effective."21 As partners the firm of Phelps and Bradstreet flourished, eventually occupying six floors of Minneapolis's Syndicate Block, with a staff consisting of a collector, five salesmen, twelve cabinet makers, ten upholsterers, four varnishers, three sewing girls, two teamsters, five men to receive and ship goods, and a bookkeeper.22 | ||||||

|

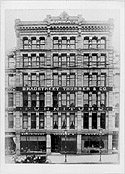

When Phelps sold his interest in 1884 to pursue banking and other business ventures, his shares were purchased by the Thurber family, Bradstreet's former employers at Gorham.23 Under the name Bradstreet, Thurber, and Co., the establishment remained in its location at the Syndicate Block throughout the remainder of the 1880's and into the early 1890's (fig. 4).24 The business offered popular period reproduction furniture as well as the latest in European and East Coast fashions. While his friend Perry Robinson later recalled that he was, "not quite certain that Mr. Bradstreet now would approve of everything that was in those windows then," Robinson related that the overall impression of the business at the time had been of an establishment, "obviously in advance of its surroundings."25 The business catered predominantly to Minneapolis's growing upper class; first generation families of wealth who wished to display their affluence and taste. The Minneapolis Business Souvenir wrote in 1885 of the enterprising business, "This is one of the few firms whose presence in our city has had a very marked influence in moulding a taste for fine goods. Through their influence a large demand has been created for fine and artistic furniture, such as could not have been sold here a few years since."26 While it appears that at some point the company endured serious business trials, Bradstreet seems to have emerged from the ordeal relatively unscathed; and the recollections of his friend, Perry Robinson, concerning the events serve to further illustrate the primacy Bradstreet placed on the integrity of his art, rather than its ability to simply turn a profit. Robinson wrote:

In 1884, the year he became associated with the Thurbers, Bradstreet took up stylish quarters at an exclusive boarding house owned by William Sheldon Judd (fig. 5). Its grounds covered an entire city block across from the Minneapolis City Hall, with extensive lawns and gardens surrounding the mansion.28 It was the most fashionable boarding house of the time and, according to the city directory, was "the residence of many people of social standing."29 Bradstreet was given free reign to remodel the rooms he occupied at the Judd House and the unique environment he created for himself is an expression of his early tastes. He altered the architecture of one room to include Moorish arches and painted a band of pseudo-Arabic script around the upper boarder, accenting the room with plush pillows, incense burners, and works of Oriental art (fig. 6). |

||||||

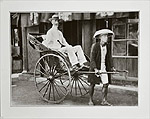

| During the last quarter of the 19th century, Bradstreet, like many other designers of the time, was especially interested in the art of the Orient and became well known as an enthusiastic advocate of the contemporary vogue for Oriental aesthetics.30 It has not yet been established whether Bradstreet's Orientalist tastes were developed through direct exposure to the Near East or simply in response to the Orientalist vogue popular at the time in Europe and on the East Coast. While records have not emerged recording early trips to the Near East, it is known that Bradstreet traveled extensively in the last quarter of the 19th century, and by 1889 had become especially interested in Japan and its art.31 Throughout the rest of his life Bradstreet expanded and refined his appreciation for all things Japanese, visiting the country nine times in total.32 As a savvy connoisseur with strong connections on the East Coast, however, Bradstreet was well aware of the Japonist craze before his first visit to Japan in 1889. Michael Conforti argues that Bradstreet may even have been exposed to Japanese aesthetics prior to coming to Minnesota, pointing to the significant role played by Newburyport, the town in which he was educated, in the early American trade with the Far East. Conforti also raises the possibility that Bradstreet, while still a resident of Providence, may have seen a copy of Hokusai's Manga as an edition is known to have been acquired by the library of his first employer, Gorham Manufacturing, shortly before he left the company.33 It is not known whether Bradstreet attended the Philadelphia Exposition in 1876, where the American craze for all things Japanese began; but, at the very least, he must have recognized an emerging market opening to the type of exotic aesthetics which he favored. As early as 1878, influences of "Japanesque" aesthetics appear in written and pictorial material associated with Bradstreet's businesses (figs. 7-8). These early occurrences, however, are somewhat clumsy and unsophisticated in their implementation; and during the 1890's Bradstreet's knowledge of Japanese life and art grew steadily as he traveled extensively throughout Japan, collecting, educating himself, and forging relationships with dealers in Japanese antiques and fine art (figs. 9-12). He brought back what one friend described as "wagon-loads" of "plunder" from around the globe34 and became a popular guest lecturer as his reputation as an authority on Japan grew (fig. 13). | ||||||

|

Bradstreet's travels throughout the globe in the concluding decades of the 19th century also brought him into contact with prominent artists and trends in Europe. He became a great admirer of the art of the Spanish and Italian Renaissance35 and was also especially enthralled by Whistler and the Aesthetic movement in England in addition to his admiration of Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement.36 He used his time onboard ships to make connections with potential clients and became increasingly involved in international clubs, including the National Art Cub of New York, the Ends of the Earth Club of New York and London, and the Royal Asiatic Society of London, establishing contacts that would be crucial in the formation and dissemination of his mature creative style.37 Additionally the business and personal relationships he was establishing locally, encouraging Minneapolitans to value and appreciate art, and whetting their appetites for luxury, quality, and exoticism, helped to prepare a fertile and receptive ground for his increasingly ambitious endeavors. In their tribute to his life, the Minneapolis Institute of Art recalled of this period:

While Bradstreet's first twenty-five years in Minneapolis produced very little that has as of yet proven to be of lasting artistic significance, the period was essential to the development of contacts both at home and abroad, to the refinement of his tastes, and to the accumulation of the experience and capital needed to start his most ambitious venture—the Crafthouse. |

||||||

| II. Bradstreet and the Minneapolis Crafthouse In 1893 the Bradstreet-Thurber building and its stock was severely damaged by fire, resulting in losses suffered by the company estimated at nearly $100,000.39 It is unclear whether Bradstreet and the Thurbers had disassociated just before or just after the fire, but whatever the case may be, after the fire their association was at an end. The Thurbers returned to Rhode Island and Bradstreet resumed operating under his own name solely for the first time in fifteen years. In 1901, Bradstreet, with Frank Waterman and Fannie M. Jaquess, incorporated John S. Bradstreet and Co. with capital stock of $ 50,000. 40 |

||||||

| After the Syndicate blaze, the company occupied a number of temporary homes and, in October of 1903, Bradstreet announced the business' removal to the Faries's residence at 327 South Seventh Street, to which he had secured a ten-year lease.41 Throughout the remainder of the fall, Bradstreet remodeled the building, installing electricity, and constructing a large attached shop and showroom.42 Prior to the grand opening, he redesigned the façade of the house, transforming it from an Italianate villa into an Oriental retreat. His activities greatly piqued the interest of his patrons and neighbors, but he insisted on maintaining suspense until the grand opening in January of 1904, which met with an enthusiastic review in the Minneapolis Journal.43 | ||||||

|

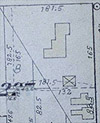

Bradstreet steadily expanded the space, beyond the original alterations, to accommodate his growing business. While the architectural floor plans for the alterations appear to have been lost, the extent of the changes he made to the property in the decade after the Crafthouse's opening can be understood by comparing detailed lot illustrations from the 1903 Minneapolis City Atlas (fig. 14) with those from the 1912 issue of the Insurance Maps of Minneapolis (fig. 15). By 1912, Bradstreet had developed the property substantially and acquired adjacent lots on which he had built a complex of showrooms, offices, workshops, and storage areas. Although the manner in which the Crafthouse attractively marketed interior furnishings has been previously known through photographic records, the 1912 lot details provide new insight into the functioning of the Crafthouse as a business, the occupation of which was to manufacture these furnishings by hand. While the 1904 write up of the Crafthouse in the International Studio listed only approximately thirty workers in Bradstreet's employ, by 1910, the Minneapolis Journal reported that the Crafthouse's workforce had increased to more than eighty men.44 To accommodate this number of craftsmen and the great demand for product, Bradstreet built facilities for cabinetry, painting, gilding, upholstery, ceramics, and constructing lighting fixtures. He also constructed a larger second office separate from his own private business quarters. |

||||||

|

Throughout his years as one of the prominent citizens of Minneapolis, Bradstreet had become widely known as a gentle, sensitive, and artistic soul and the Crafthouse was the ultimate expression of his self, and his tastes (fig. 16). In dramatic contradistinction to the stolid and imposing brick department store which Bradstreet, Thurber, and Co. had occupied (fig. 4), the Crafthouse was as much an artistic entity as were the items displayed within. The interior, exterior, and grounds were designed with an overarching objective—to infuse artfulness, novelty, and beauty into every detail. The result, in the spirit of the German concept of gesamtkunstwerk, was an artistic oasis entirely set apart from the world around it. The visitor entered the enclosed grounds through a small Japanese gateway, framed by supports of rough, stippled cement, colored a rich, quiet green and accented by small green stones set into the cement to achieve the impression of velvety moss covered with lichens.45 The gateway was crowned by a floral woodcarving which Bradstreet had brought back from a Japanese temple. Impressed into the cement underfoot was the tatsu, (a circumscribed dragon) which served as the Crafthouse's logo and symbolized the meeting of the arts.46 As an establishment that sponsored concerts and exhibited art and antiques from around the world in addition to producing decorative art of the finest quality and design, the logo greeting the Crafthouse's guests seems especially well-chosen. |

||||||

|

While the walkway led to the main entrance to the Crafthouse, winding paths invited the guest to stroll about the gated grounds to enjoy the lush lawns, verdant gardens, and picturesque details of the building.47 The building itself was covered by a soft gray stucco accented with small pebbles utilized to produce a lichen effect that simulated the effects of age and exposure to the elements.48 In a further departure from convention, Bradstreet sought stylistic harmony rather than unity in the unexpected combinations of exterior elements, which were orchestrated to delight the visitor with constant surprise and to sustain a lively interest in touring the grounds. With a disregard for symmetry, Bradstreet introduced pieces brought back from his travels throughout England, India, Spain, Italy, Japan, and Egypt in the quaint and artistic touches to the entrances, windows, and grounds. "All the world has contributed here," Bradstreet & Co. announced in a promotional booklet, "and the effect is most picturesque. The odd and curious corners of the Orient have been searched, not once but many times, in quest of material and ideas for this wonderful shop, and the result has been a rare collection of the beautiful."49 The buildings and the idyllic environment within which they were nestled stood in sharp contrast to the surrounding neighborhood; the varied window treatments, gothic tower, Italianate sculpture, and Japanese garden all announcing to the passerby Bradstreet's design theory of "the fellowship of good things." |

||||||

| The eclectic scheme announced by the exterior of the Crafthouse was carried to conclusion in its interior which functioned as a craft shop, showroom, and museum of sorts. The main entrance (fig. 17), located between the original house and Bradstreet's initial additions, opened into a small vestibule paneled in Bradstreet's signature jin-di-sugi style (fig. 18). To the left of the entrance hall stood the original house which contained Bradstreet's office in the front and a textile room and craft workshops at the back. Bradstreet's personal office (fig. 19), like his private dwellings, expressed his taste at its most uncompromised. A warm but masculine aura was achieved in the wall treatment by contrasting a dull copper stenciled wallpaper with luxurious cypress wainscoting and rich-grained sassafras paneling. The Old English design of the stained glass window and the colonial furniture from the Bradstreet homestead in Massachusetts attested to Bradstreet's heritage. The details of the room, however, revealed his love of the Orient. He decorated the office with cherished items from his travels, including a Japanese print, a gourd vase, small statues of Buddha, and an exquisite Japanese bookcase constructed of soft brown wood with large sliding doors adorned with a delicate cherry blossom motif.50 The combined effect of the office not only argued for Bradstreet's immense skill as a designer of interior spaces, but also asserted his prestigious lineage and impressive credentials as a traveler and connoisseur of Oriental art. | ||||||

| To the right of the entrance hall a large general showroom, approximately fifty feet in length by forty feet in width, connected the original house to the Crafthouse's main hall. This general showroom (fig. 20.) displayed Oriental pieces, period reproductions, and other items manufactured by Bradstreet's craftsmen. It was accented by two windows, one East Indian and one Egyptian, which admitted sunlight into the interior. Typical of Bradstreet's taste for the eclectic and exotic, the windows coexisted harmoniously achieving an effect that one visitor described as wholly romantic, "even though they look out on the prosaic streets of a prosaic city."51 Adjacent to the general showroom the visitor entered into the Crafthouse's main hall (figs. 21-22). An expansive two-story room, open to its peak, the hall gave the immediate impression of a gothic chamber with its large walnut hammer beams supporting the vaulted ceiling.52 Skylights designed to provide light without glare or excessive shadow were installed on the east side of the ceiling, admitting sunlight which struck the gold sackinto53 cloth wall coverings, creating a soft diffused light and further enhancing the mystical atmosphere.54 A small minstrel's gallery (fig. 22) was constructed over the north Japanese entrance which welcomed visitors from the exterior into the hall.55 Around the upper register of the room ran a series of Japanese frescoes and on the floor, completing the eclectic effect, lay large Oriental carpets. A relatively small lattice window was placed in the long west wall opposite the room's large fireplace, which was flanked by a pair of plaster elephant heads—mementoes rescued when Minneapolis's Grand Opera House, for which Bradstreet had designed a Moorish interior in his younger days, was torn down in the 1890's.56 The walls were adorned with framed paintings, Japanese prints, tapestries, and small jin-di-sugi carvings.57 Bradstreet spaciously and meticulously exhibited the cream of his collection in the Crafthouse hall. Photographs suggest that special attention was given to objects from Japan and to his signature jin-di-sugi furniture, but he was not slavishly devoted to any single aesthetic and he also introduced period reproductions into the space with remarkable ease. One visitor wrote, "The room is admirably planned, dignified in proportions, and perfect in atmosphere. Each object of the exhibit is given its due both in space and lighting, there is no injustice to any object through an obtruding neighbor. This room is the final argument of the Crafthouse in its plea for breathing space and beauty."58 | ||||||

|

In addition to its commercial focus, the Crafthouse strove to provide a "home for the handicrafts" and a "museum of decorative arts."59 Bradstreet often equated the experience of traveling throughout the shop, with its artful combination of the Orient and the Occident, to the experience in miniature of traveling the world.60 The shop's design encouraged visitors to seek and discover treasures in its quaint corners with the same delight Bradstreet had enjoyed in originally discovering them in the remote stretches of the world. Although Bradstreet became a tastemaker to the city, he was not interested in dictating taste or peddling sophistication. Rather, he wished to create an atmosphere in which to present his designs and to cultivate among his visitors a love of the exotic and of the thrill of discovering and savoring unique treasures. Edwin Hewitt, a good friend and accomplished architect, reminisced of the experience:

In the spirit symbolized by the Crafthouse's logo—the meeting of the arts—the Crafthouse was also the host to many elegant dinners, concerts, special exhibits, and other soirees. In the evenings, two large wrought iron chandeliers provided a soft amber light in the main hall, and the grounds were lit by Japanese lanterns.62 The experience of an evening's entertainment at Mr. Bradstreet's must have indeed been a whimsical and enchanting experience. His efforts to find the beauty in everything extended to all aspects of his life and associations and one friend recalled after his death that "the company which counted him an intimate, found in him a reinforcement of all their gentler and better selves."63 |

||||||

| In addition to his desire to bring nature into the interior of the Crafthouse through abundant arrangements of fresh flowers,64 Bradstreet's profound regard for the beauty of the natural world was further manifested in the manicured lawns and lovingly landscaped grounds surrounding the Crafthouse. Inspired by a tour with Josiah Conder through the most celebrated Japanese gardens of the time, Bradstreet became determined to incorporate Japanese gardening into his own life.65 One of his first attempts appears to have been in the gardens of the Judd property, where he boarded. Like Bradstreet's other known early attempts to introduce Japanese art and aesthetics to Minnesota, the Judd garden (fig. 23) appears to be arranged in a rather simplistic and amateurish fashion consisting simply of a small pond, a stone lantern, bronze crane, and thatched shelter. His work at the Crafthouse attested to a much more confident and knowledgeable hand (fig. 24). Placed near the Japanese entrance to the main hall (fig. 25), the garden, as one visitor observed, provided a relaxing point to pause "at the threshold of the building itself, [where] the passer-by may freely linger, and take undoubted inspiration to his own home life." Based upon the Japanese principle of presenting nature in miniature, the garden centered around a small pool upon which white lilies and pink and purple lotuses floated in season (fig. 26). The garden overall, however, was consistent with the relatively insignificant role played by flowers in the Japanese garden, focusing rather upon carefully placed shrubs, plants, and potted dwarf trees arranged on the bed of rock and gravel which contained the pool. Adjacent to the pond was a rock garden surmounted by a small bronze dragon from whose mouth a small stream of water trickled, flowing lazily downward from rock to rock. A small bridge, crafted from planks of an ancient junk which had been exhibited by the Japanese government at the St. Louis Exposition, served as a walkway over the pond. Other Japanese elements were introduced throughout by the inclusion of bronze cranes, bird houses, and small stone lanterns which cast a luminous glow onto the pond when lit in the evening hours. While the overall effect was that of a Japanese garden, the space was also remarkable for the ease with which Bradstreet incorporated into it plants and trees native to North America. Gustave Stickley, the major designer from Syracuse, concluded his enthusiastic review of it in his journal The Craftsman, with the praise, "The unobtrusive work of Mr. Bradstreet is worthy to initiate a national movement."66 | ||||||

| The grounds and the Crafthouse united to form a Utopian environment in which art, music, fellowship, literature, and the quest to find beauty in all things could be pursued. While his love of beauty for beauty's sake was strongly influenced by the Aesthetic movement, Bradstreet's desire to preserve the integrity of the handicrafts he produced—and the handicraft tradition—through the establishment of an environment devoted to this purpose, was modeled upon William Morris's Kelmscott Manor.67 "In these days of a surfeit of machine-made everything," Bradstreet asserted, "the demand is constantly increasing for articles that bear the stamp of individuality, rather than the label of the factory."68 Bradstreet employed a large contingent of highly skilled craftsmen, many of Scandinavian and Japanese origins.69 William Eckert, an interior decorator who started as Bradstreet's apprentice, recalled that Bradstreet was devoted to apprenticing young men in whom he identified potential. Bradstreet took an intense interest in their training and, as their skills grew, gradually increased their responsibility until they were able to carry out jobs on their own. Once they had progressed to this stage, Bradstreet never interfered with their work. Although he had strict rules for his employees, barring smoking, drinking, and gossip, he enjoyed a familial relationship with them and was, as Eckert recalled years after Bradstreet's death, worshipped by many of the younger men for the kindness and fairness he had extended to them.70 Photographs record a happy environment showing Bradstreet associating with his workers in the Japanese garden (fig. 27) and Crafthouse workers cavorting with the studio's pet cat (fig. 28). "It was a delight," his friend Hewitt recalled, "to see how affectionately his workmen strove to realize his ideas. Long years of association with him bred an affection and respect due to a master." The creative environment of the Crafthouse also provided the locale for Bradstreet and his Craftsmen to develop the jin-di-sugi style of woodcarving, a signature style that would attract wide attention, making his furniture and room interiors startling additions to the American decorative arts revival. | ||||||

|

III. Jin-di-Sugi, Bradstreet's Signature Style

Bradstreet, who had acquired Japanese temple screens at the same time as the Boston Museum,75 was similarly fascinated by the technique and became determined to devise a method to reproduce it more quickly. After long periods of study and trial, Bradstreet arrived at a method of successfully duplicating the effect by brushing scorched cypress with a wire brush to remove the soft grains of the wood, leaving behind the raised grain of the hard fibers.76 The wood was then washed and waxed to achieve a soft, velvety finish that could be carved, stained, or painted upon. Achieving this method around the turn of the century,77 Bradstreet applied for patents and began to incorporate the technique into designs for furniture and paneling, developing an aesthetic that stressed the creative utilization of nature in introducing beauty into the everyday environment. The firm began promoting the sugi (an abbreviation for jin-di-sugi) line as early as 1903 and specifically stressed the uniqueness of their product, emphasizing in their marketing campaigns that they were, "the only manufacturers of this Special Wood Treatment."78 |

||||||

| Bradstreet effectively applied the technique to paneling but also used it on the surface of traditional Western furniture designs, marrying Western and Eastern aesthetics in the most sophisticated manifestation of his theory of "the fellowship of good things." Carvings of such motifs as birds, dragons, fish and lotus blossoms floating upon stylized waves, imitated the Japanese love of taking inspiration from nature and abstracting from it, often making the shape the image assumed subservient to the whims of the wood's grain. While the retention of traditional furniture designs into which the carvings were incorporated perhaps prevents discussion of Bradstreet's sugi style as entirely progressive, the technique of the carving itself was extremely innovative and closely aligned to the principles of the contemporary Art Nouveau movement. Louis Comfort Tiffany, for one, recognized the originality of the new product line, enthusing, "I consider your furniture, as designed and brought out in the Jin-di-Sugi finish, the most unique and artistic treatment of wood yet produced."79 The treatment quickly became recognized as Bradstreet's specialty and clients from New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and other locals visited the Crafthouse to obtain sugi pieces.80 | ||||||

| IV. Bradstreet and Interior Design Throughout his career Bradstreet was also devoted to designing interior spaces. At the height of his career he collaborated with such important American decorative arts firms as Tiffany and Co., Rookwood Pottery, and the Grueby Faience Company, and his clientele extended not only to many of the best homes in Minneapolis, but far beyond to both Coasts and into Canada.81 In concurrence with contemporary American design reform concerns, Bradstreet was dedicated to introducing the pleasures of an artistic home into the daily lives of those he served and, in executing his commissions, sought to complement the family's personality through the décor of their home. Before embarking on the first stages of planning, he met with the family, including the children, in order to get a sense of the atmosphere that would be best suited to the family's dynamic.82 His services were not limited to the wealthy and he was equally willing to accept small commissions; in fact, it was recalled of him that he had done some of his best work in homes of modest means, although no examples of such interiors have been yet discovered.83 |

||||||

| While known surviving examples of interiors by Bradstreet are extremely rare, several important examples of his mature sugi style have emerged in recent years. The most complete sugi interior to have come to light was once part of the Prindle home in Duluth. The living room from the home, designed circa 1906, is now exhibited as a period room in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (figs. 29-30). Particularly valuable for its preservation of an intact interior containing both its original furniture as well as structural detailing, the room illustrates Bradstreet's assiduous attention to color and theme as well as the manner in which he combined sugi elements with glasswork by Tiffany and Co., one of the most fashionable East Coast art firms of the time, to achieve a unified design. | ||||||

| The moss green tone of the walls combined with the dark wood paneling establishes the room's dusky color scheme, drawing the attention of the eye to the room's sources of light. Two large sets of windows drew sunlight into the interior and also provided for the natural beauty of a vista of Lake Superior to be incorporated into the room's many artificial variants on the theme of nature. Soft electric light was provided by lamps, a Tiffany chandelier, and Tiffany wall sconces placed throughout the room. A Tiffany dragonfly lamp appears on the desk, and gold favrile shades attached to the sugi bases of the wall sconces (figs. 31-32) and main chandelier added warm golden accents to the room. Additional favrile elements are introduced in the aqua-green tiles surrounding the fireplace, all uniting to provide a superb example of the manner in which Bradstreet successfully combined sugi elements with glasswork by Tiffany and Co. to achieve a unified design. | ||||||

| The rug and velvet curtains continue the predominant dark green color scheme while introducing light pink accents in their lotus blossom borders. Cypress wainscoting with intermittent carved sugi panels based on themes from nature comprise the lower portion of the wall décor, with a large sugi panel above the fireplace (fig. 33). This panel, which serves as one of the focal points of the room, establishes the room's decorative motif of the lotus blossom and lily pad. The woodworking of the mantel follows in part the Japanese prescription for allowing the natural grain of the wood to dictate the composition, an element which can be seen particularly well in the break of the wave in the lower center of the panel. In their asymmetry and adoption of the Japanese practice of stylizing and abstracting from nature, these sugi elements clearly owe a compositional debt to the art of Japan. | ||||||

| The theme of the lotus is continued in the decorative treatment of several of the room's more heavily embellished sugi pieces, including the lotus tea table and the Steinway piano (fig 34). Like the driftwood footstool also included in the decorative scheme, two tables incorporating driftwood planks suggest the contrast between nature's treatment of wood and the artisan's handling of wood. The panel forming the top of the larger of the two tables (fig. 35) is marred by several large knots in the wood. Rather than rejecting the panel as flawed, however, the craftsman chose a decorative motif of a carved dragon and small turtle which incorporate, as essential parts of their form, the ridges and crevices of the knots. Again, in this way, the woodwork in the Prindle Room demonstrates its debt to Japanese precedents. An article published in a 1912 edition of The Craftsman concerning the sugi finish in general, reveals that Japanese craftsmen to whom, "a knot in a board with the irregular grain of the surrounding wood was exquisite, something to be preserved, something to furnish a decorative note to the room in which it was placed," similarly incorporated natural "defects" into their designs.84 In this way, the carving on the tabletop exhibits both a thorough acquaintance with Japanese technique and a sophisticated and capable assimilation of it by Bradstreet's craftsmen. | ||||||

| While all of the elements of the room cannot be discussed here, the room as a whole illustrates Bradstreet's masterful understanding of color and light and demonstrates one of the manners in which he introduced sugi woodworking into the design for a domestic interior. The Prindle home was situated in the far reaches of the Northwest, then a provincial region, yet the room is neither provincial in its design nor does it copy from fashions first made popular on the East Coast or in Europe. Bradstreet's extensive use of his own sugi style, combined with glasswork by Tiffany and Co., assured the Prindles of a room characterized by luxury and taste, entirely original in concept and at the cutting edge of artistic experimentation. | ||||||

| Bradstreet's sugi style was appreciated not only in the Northwest, however, and a suite of sugi furniture commissioned for an Adirondack lodge85 suggests the wider appeal of the style, as well as the diverse results of which it was capable. While the design of the original interior environment in which the ensemble was placed is unknown, the suite as a whole is characterized by a unified design of form, color, and ornament. Comprised of a settee, two side chairs, a curious bergère, and a lotus table, the suite combines traditional western furniture designs with lavishly carved sugi panels that meditate upon themes from nature. The cypress panels were burnished to a rich, velvety finish and combined with more subdued natural motifs to achieve a softer synthesis of the sugi style than that employed in the Prindle home. Stained a luminous dark green, the pieces contain a fascinating intrinsic range of colors, varying subtly under different light conditions from a cool blue-green to a rich brown-green. The carvings, more softly and realistically rendered than those in the Prindle Room, reveal a superb use of the natural line of the raised grain to form integral parts of the composition. While the compositions are free-flowing in comparison to their stylized counterparts in the Prindle room, they are equally elegant in design and execution. | ||||||

| The decorative panels of the settee (fig. 36) and side chairs (figs. 40-42) feature the most delicately rendered sugi elements in the suite. The carvings featured in the panels again linger on the theme of the lotus blossom and lily pad, themes especially loved by Bradstreet and greatly inspired by his admiration for the art of Japan. The blossoms are languorously strewn across the panels rather than forced into decorative contortions, adding to the harmony of the designs. Variety is achieved through the introduction of additional natural elements including turtles, frogs, and a dragonfly. The smooth, tactile body of the settee's plump frog (fig. 37) as well as the curving head and neck of the turtle and the interior structure of the flower above him (fig. 38) all serve as especially remarkable examples of the skilled artisan's ability to utilize the natural line of the raised hard grain revealed in the sugi process to form integral parts of the composition. While the sugi technique employed to create the panels for the suite remains firmly conversant in its Japanese origins, the compositions are far less stylized than those in the Prindle room and are less overtly indebted to Japanese models. The arms of the settee feature stylized sugi dolphins (fig. 39) related to those on the arms of the Prindle's Steinway piano. In this case, however, they are elongated to complement the more delicate form of the settee which they grace. The creatures with dolphins's heads—but with fish-like bodies—also serve to wittily evoke both the Japanese and Western prototypes to which the design owes its origins, recalling the dolphins commonly featured on the arms of empire-era settees as well as the popularity of the fish motif in Japanese art. | ||||||

| The harmonious coexistence of Eastern and Western design principles was central to Bradstreet's philosophy of "the fellowship of good things," and the sophisticated merging of styles which he achieved is key to the suite's success. The value sugi products placed on beauty, honesty of craftsmanship, and the incorporation of natural motifs drew equally from the Arts and Crafts tradition, the Aesthetic movement, and the art of Japan. Indebted to its diverse roots, Bradstreet's sugi style was remarkably effective and versatile; equally suited to integration with the other exotic elements of the Prindle room and its heavy Arts and Crafts furniture as it was to the delicate forms of the pieces of the Adirondack suite. | ||||||

| The presence of the lotus table in both ensembles(fig. 43-44) suggests the privileged place the design held within Bradstreet's oeuvre and also suggests his success in promoting this piece in particular, within the marketing campaign for the new style in general. Featured in local advertisements in The Bellman more frequently than any other sugi design, the lotus table was also marketed directly to at least one private patron. In 1903, Bradstreet's business partner Frank H. Waterman, addressed a letter to a patron from New York to introduce the new piece. "Your known appreciation of the beauty in art has prompted us to write you in reference to this new work," Waterman wrote. "The possession of this table will prove as satisfying as a grand painting by one of the 'old masters' and similarly, besides being exclusive it is difficult to state its real worth in dollars and cents."86 The piece was available for a specific price, however, and could be purchased for $65.00.87 Although the design was executed multiple times, individuality was not entirely sacrificed; and of the four known extant versions, none is exactly similar to another. The tables, even when based on a specific design, were still each produced by hand and could be subtly varied in their carvings, stains, and surface treatments to render each version unique and artistically expressive.88 As the signature piece of Bradstreet's signature style, the lotus table embodies his desire to introduce luxury, beauty, and honest craftsmanship into the artistic home. In concluding his letter to the prospective client, Waterman wrote, "In your drawing room, library, den, reception room—a present to your club—or placed in your private office—Wherever you may locate it, you will find it a source of pleasure."89 | ||||||

| V. Conclusion Bradstreet's effect upon the cultural life of the city of Minneapolis was profound and it is impossible to consider his career apart from the city to which he devoted most of his adult life. His importation of aesthetics and design principles absorbed during his many travels and his opening of the Minneapolis Crafthouse contributed to the city's emerging consciousness of the scope of international art and its own place within the arts community. "The fact is," a Crafthouse publication pronounced in 1905, "that the prosperous existence of such an institution as the Bradstreet Craftshouse, based primarily on local support, means that Minneapolis has grown beyond the pioneer period and is now a city of culture, artistic perception, and wealth which enables it to gratify an educated taste."90 Bradstreet was not merely a symptom of the city's development, however, as much as he was one of the propelling forces behind it. His inexhaustible devotion to promoting the refinement of taste both privately and civically contributed to the development of a community amenable to the opening of his Crafthouse, an institution which garnered an international reputation and attracted visitors from around the globe. As an artist Bradstreet was perceptive and sensitive, willing to acknowledge his sources of inspiration. His mature eclectic style gestated slowly until, with the opening of the Minneapolis Crafthouse, he emerged fully as an original and innovative artist with a unique contribution to make to the American decorative arts revival. Working in the American Northwest, an area not previously noted for progressive interior designs, Bradstreet exhibited in his jin-di-sugi style the manner in which the art of Japan could provide inspiration for departure from stale historicist style and demonstrated in the interior designs executed in his region, strong links to the international design reform movement. |

||||||

|

Acknowledgements: I wish to express my gratitude to my adviser, Dr. Gabriel P. Weisberg, who suggested this topic as the basis for my dissertation research and to whose instruction, advice, and constant encouragement I am greatly indebted. I would also like to thank the following individuals and institutions for the assistance they have provided to me throughout the course of my research: Jennifer Carlquist, Jennifer Komar Olivarez, Janice Lurie, Ken Krenz, and Debra Hegstrom at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Steve Nielsen and Kathryn Otto at the Minnesota Historical Society. Patty Dean at the Museum Collections Department of the Minnesota Historical Society. Todd Mahon at the Hennepin History Museum. Barbara Bezat at the Northwest Architectural Archives, University of Minnesota. Wendy Anderson at the Minneapolis Public Library. JoEllen Haugo and Toni Miller at the Special Collections Department of the Minneapolis Public Library. Steven J. Ristuben at the Office of City Clerk, Minneapolis City Hall. Bob McCune and Craig Steiner at the City Archives, Minneapolis City Hall. John Helgeson at the Municipal Building Commission Archives, Minneapolis City Hall. Leslie Johnson and Donna Lyons at the Catholic Charities of St. Paul and Minneapolis. Ray Erickson at the Minneapolis Grain Exchange. Annie Young at the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board. Daniel Necas at the Immigration History Research Center, University of Minnesota. Dr. Erika Lee, History Department, University of Minnesota. Amy Kurlander at the Japan Society Gallery, New York. Tim Hallman at the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco. Barbara Gilbertson at the Minnesota Department of Revenue. Dr. Michael Hussey at the National Archives and Records Administration. Tessa Veazey at the Archives of American Art. Kristen Wetzel, David Aylsworth, and Yuki Sato at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen and Amelia Peck at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. S. Jordan Kim at the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum. Mariam Touba at the New York Historical Society. Mike M. Thornton at the Art and Architecture Department, New York Public Library. Gerald W.R. Ward at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Paul at the Library of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Paula Bradstreet Richter and Kristen Weiss at the Peabody Essex Museum. Ed Bell, Ryan Thomas Maciej, and Elizabeth A. Marzuoli at the Massachusetts State Archives. Janice Chadbourne and Kim Tenney at the Boston Public Library. Hina Hirayama at the Boston Athenaeum. Nancy Carlisle at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. Lenox Brands Consumer Services. Dr. Mark N. Brown and Tim Engels at the John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. Jennifer Morrison at the History and Special Collections Department, Grand Rapids Public Library. Anna Buruma, archivist at Liberty & Co. Kathleen Weber at Carson Pirie Scott. Jane Prentiss at Skinner Auction House. Leah Stevens at Briggs Auction Inc. Jodi Pollack at Sotheby's. I also wish to thank the following dealers who have kindly corresponded with me: Mark Golding at The Arts and Crafts Home, Jerry Cohen at Craftsman Auctions/David Rago Art & Auction Center, Stuart Holman at Stuart Holman Auctions, Isabella Corble at Berwald Oriental Art, Martin Levy at H. Blairman & Sons Ltd., Jill West at Circa 1910 Antiques, Edith Frankel at E&J Frankel Ltd., John Alexander at John Alexander Ltd., Robert Berman at Robert Berman Antiques, Robyn Turner at Robyn Turner Gallery, and a very special thank you to Robert Edwards at American Decorative Art. I also wish to extend special thanks to the following individuals: Fritz Nelson, Mark Hammons, Mark Perrin, Ronald Beining, Jon Bjornnes, Peter Sturm, Kendahl Sweet, Robert Levine, Nick and Sandra Hay, Scott McGinnis, Joseph Cunningham, Bruce Smith, Robert Furniss, Robert Glancy, Dr. Donald J. Doughman, James V. Toscano, Darrell Peart, and Leone Medin. 1. Obituary, Minneapolis Journal, 10 August 1914. 2. This phrase, which seems particularly apt for much of the mass-produced imitative work of the period, is taken from Beverly Brandt's article, "Worthy and Carefully Selected: American Arts and Crafts at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, 1904," Archives of American Art Journal 28, no. 1 (1988): 2-16. 3. "Fine Collection in its New Home," Minneapolis Journal, 30 January 1904. 4. As early as the 1890's Bradstreet appears to have enjoyed renown far beyond the city in which he worked. In an article appearing in a 1907 issue of The Bellman, the English journalist Perry Robinson reminisced of his friend Bradstreet's early international success: "Some fifteen years ago I was in London on a flying visit and went into Liberty's famous place. On coming away I stopped to ask some question about the duties on the things which I had bought and intended taking to America. It was the first intimation that the man to whom I spoke had had that I was from America; and the first question that he asked was if I knew a Mr. Bradstreet. He could not remember the name of the town where Mr. Bradstreet lived, so I furnished it. 'Ah, yes,' he said, 'of course. Is it not a remarkable place for such a man to be in? Could he not get much wider recognition in New York, for instance?' Undoubtedly he could; but, after all, I suggested, the place for a missionary was among the savages." Perry Robinson, "John S. Bradstreet and his Work," The Bellman 2, no. 20 (18 May 1907): 598. 5. "Notes on the Crafts," The International Studio 23 (1904): 335-37. This article appeared in a supplement to The Studio concerning the international art scene. Also featured in the article is Tiffany and Co. in New York and the studios of Mrs. Priestman in Philadelphia. 6. In 1905, Bradstreet & Co. boasted in a promotional brochure, "Bradstreet's has become the mecca of all such lovers of art, whether they come from the great cities of the east or the small towns of the west, and it is one of the important sights for Minneapolis visitors." John S. Bradstreet & Co, Promotional Booklet (Minneapolis: Byron and Willard Co, 1905). A brief biographical essay on the history of the Minneapolis Skylight club, of which Bradstreet was a founding member, asserts that the clientele of the Crafthouse, "extended to both coasts of the United States and into Canada," and an obituary published by the Minneapolis Tribune additionally comments that "his neighbors must have been surprised could they have known how wide was his fame." Bergman Richards, Skylight Club "Red Book," 6th ed. (Minneapolis: Harrison & Smith, 1965); Obituary, Minneapolis Tribune (11 August 1914), 6. 7. Obituary, Minneapolis Tribune. 8. Biographical material is gathered primarily from the Bradstreet obituaries. I also feel compelled to give special credit to two individuals, Miriam Lucker Lesley and Fritz Nelson, who have both contributed considerably to the compilation of biographical material on Bradstreet. Lucker Lesley compiled the first known body of academic research on Bradstreet for her unpublished master's thesis written for the Department of Art History, University of Minnesota, 1941. While Lucker Lesley's primary research was fairly limited, she contributed invaluably to the present knowledge of Bradstreet through a series of interviews which she conducted with individuals who knew him and which she documented in her notes. Fritz Nelson significantly furthered the primary research begun by Lucker Lesley for his directed research paper, "First Apostle: John Scott Bradstreet in Minneapolis," written for the Department of Art History, University of Minnesota, 1980. While Nelson's manuscript was never published, his work greatly expanded the body of primary sources referenced by subsequent writers and I feel especially indebted to his creative and substantial contributions. 9. 1860 U.S. Census, Massachusetts, Essex County, Rowley, p. 132, line 14. 10. Information gathered from the Gorham Pay Records, Volumes A-E, and the Providence City Directories, 1863-1872. Both in the collection of the John Hay Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. 11. Minneapolis City Directory, 1873. When the firm of Barnard, Clark, and Cope was taken over by Edward C. Clarke in 1874, Bradstreet continued as an employee of Mr. Clarke until his shop closed in 1875. Minneapolis City Directory, 1874. 12. Miriam Lucker Lesley, "John Scott Bradstreet: Minneapolis Interior Decorator," (Master's thesis, University of Minnesota, 1941), 1. Copy residing in the collection of the library of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. 13. Richards, Skylight Club. 14. William C. Edgar, "John Scott Bradstreet," The Bellman 17, no. 422 (15 August 1914): 215-16. 15. Bradstreet's temperament is characterized in this manner in nearly all written accounts referencing his personality. A few such examples include the obituaries published in the Minneapolis Journal and in the Minneapolis Tribune; The memorial statement published in the Bulletin of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts 3, no.10 (October 1914): 25; Robinson, "John S. Bradstreet and his Work," 597-600; and Edwin H. Hewitt, "John S. Bradstreet—Citizen of Minneapolis: An Appreciation of his Life and Work," Journal of the American Institute of Architects 4 (October 1916): 424-27. 16. Edgar, "John Scott Bradstreet," 215-16. 17. Miriam Lucker Lesley, "John Scott Bradstreet: Minneapolis Interior Decorator." (Notes for master's thesis, University of Minnesota, 1941). Copy residing in the collection of the library of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Note # 1: from a conversation with William Eckert, an interior decorator who started as Bradstreet's apprentice. 18. Richards Skylight Club,; Jeffrey Hess also discusses the show briefly in Their Splendid Legacy: The First 100 Years of the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts (Minneapolis: Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts, 1985), 4. 19. Minneapolis City Directory, 1875. 20. Michael P. Conforti, "Orientalism on the Upper Mississippi: The Work of John S. Bradstreet," The Minneapolis Institute of Arts Bulletin 65 (1981-82): 3. 21. St. Paul Pioneer Press, 8 December 1878. 22. Edmund Joseph Phelps, Letter written to his Aunt Asenath (25 December 1883). Typewritten copy residing in the curatorial files of the Department of Decorative Arts, Minneapolis Institute of Arts. 23. Minneapolis City Directory, 1883-84. 24. Minneapolis City Directory, 1884-1893. 25. Robinson's recollections of his first encounter with Bradstreet again appear in his article for The Bellman. "It was as a stranger to the Northwest that I wandered by the Syndicate Block, a day or so after my arrival, and my astonished eyes met the windows of Messrs. Bradstreet, Thurber & Co. I am not quite certain that Mr. Bradstreet now would approve of everything that was in those windows then, but even as it stood, the place was so obviously in advance of its surroundings, it so evidently did not belong to the town, that mere astonishment made me go inside. As I entered, a tall (yes, quite tall) and thin (decidedly thin) man, imperfectly concealed behind a large mustache, came forward and wanted to know what he could do for me. Well, he could show me things. I couldn't afford to buy anything; but I did want to look and, if he didn't think me impertinent, I wanted to know what on earth that place was doing in that precise latitude and longitude." Robinson, "John Scott Bradstreet," 597. 26. "Bradstreet, Thurber & Co," Minneapolis Business Souvenir (1885). Photocopy residing in the curatorial files of the Department of Decorative Arts, Minneapolis Institute of Arts. 27. Robinson, 597. Much remains to be established regarding these mysterious business trials, and in fact, their existence would most likely have remained forgotten had it not been for Perry's article. Perry wrote: "I have said that he had trials. There were business trials on a large scale of which the public knew a good deal, for they involved publicity and lasted for some years." 28. Fritz A. Nelson, "First Apostle: John S. Bradstreet in Minneapolis," (Directed research paper, Department of Art History, University of Minnesota, 1980), 5. 29. Minneapolis City Directory, 1884. 30. In an article appearing in the Minneapolis Tribune in 1929, Bradstreet's friend William C. Edgar described Bradstreet's extensive use of Oriental motifs in his designs of 1887 for alterations to Minneapolis's Grand Opera House. "After the house had been in commission for four or five years, although it was not yet shabby, the owners determined to redecorate it. John S. Bradstreet, who traveled the world over in search of material for his art, was given a free hand and produced a result that made a sensation in the theatrical world. When the Grand reopened for the season, it undoubtedly had the most beautiful interior of any theater in America. Mr. Bradstreet chose to make the effect Oriental. The framing of the boxes was in Moorish lattice work, the proscenium arch rested on elephant heads with dimmed lights behind their glass eyes, the draperies and carpets were richly Oriental, the drop curtain pictured a visit of the sultan to the mosque, in the outer lobby was a statue of a Moorish water carrying girl. To carry out the theme the programs were painted with Oriental decorations in rich colors, and the boys who distributed them were robed in Oriental garments. Small colored lads, similarly arrayed, carrying Oriental trays, flagons and cups, passed among the audience between the acts, serving water. No estimate of the cost of this work had been given in advance and Mr. Conklin was fearful that the outlay would be very heavy as Mr. Bradstreet was considered an expensive artist. When the bill came in, it was found that, not to be outdone in public spirit, the great decorator had made no charge for his own services and nothing but the cost of material and the workmen's wages was included in the account." Minneapolis Tribune, 28 Oct 1929; The Moorish interiors Bradstreet executed for Minneapolis's West Hotel were further commented on by the East Coast writer Montgomery Schuyler in his American Architecture: "The interior presents several interesting points of design as well as of arrangement, but perhaps it owes its chief attractiveness to the rich and quiet decoration of those of its rooms that have been intrusted [sic] to Mr. Bradstreet, who for many years has been acting as an evangelist of good taste to the two cities, and who for at least the earlier of those years must have felt that he was an evangelist in partibus." Montgomery Schuyler, American Architecture and Other Writings (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1961), 306. 31. By the time of his death in 1914, Bradstreet had traveled to an impressive number of locales. No complete itinerary of his travels has surfaced, but a chronological account is currently being reconstructed by the author. William C. Edgar's memorial tribute to Bradstreet appearing in The Bellman lists among Bradstreet's many destinations: the eastern Atlantic Coast, Florida, California, Nassau, the islands of the Pacific, England, Germany, Spain, Italy, Sicily, India, China, Japan, and Korea. Among the additional destinations that have surfaced in newspaper and society pages are: Canada, the Suez Canal, Siam, Singapore, Java, Hong Kong, and Shanghai. 32. Henry H. Saylor, "The Japanese Garden in America," Country Life in America 5, no. 5 (March 1909): 481-84. 33. Conforti, "Orientalism on the Upper Mississippi," 13. 34. Robinson, "John Scott Bradstreet," 600. 35. This interest can be especially well seen in advertisements for Bradstreet and Co. appearing in The Bellman that feature period reproductions of Italian and Spanish Renaissance prototypes constructed by Bradstreet's craftsmen. The advertisements also often specify that the original models are antiques acquired by Bradstreet during his trips to Europe. A few examples appear in the following issues of The Bellman: 2, no. 14 (6 April 1907): 400; 9, no. 229 (3 Dec 1910): 1536; 11, no. 266 (19 Aug 1911): 228. 36. Bradstreet's close friend Perry Robinson wrote of Bradstreet's admiration of the English Arts and Crafts movement: "I imagine that if he were asked he would himself confess that he has been more influenced of late years by William Morris than by any other person or school of art, and he is himself doing a work not unlike that which Morris did. The Craftshouse is a radiating centre of good artistic impulses which can not inappropriately be compared to Kelmscott—as I believe it has already been compared." Robinson, "John Scott Bradstreet," 600. Bradstreet's admiration of Whistler is similarly evinced in a 1911 article recounting the first exhibition by the Minneapolis Society of Fine Arts in 1883: "A Whistler room in yellow, the master's favorite color, was the dream of John S. Bradstreet in the first loan exhibition ever held in Minneapolis which opened Nov. 20, 1883. The amber tints, the sunset glow, the molten gold, all held in a quasi-religious reverence by the great Whistler painter, poet and etcher had exerted a similar spell upon Mr. Bradstreet. This was heightened in a great degree when Mr. Bradstreet visited London and saw the magnificent Whistler collection of etchings, all on a marvelous velvet background. To this day Mr. Bradstreet has a piece of the original yellow drapery used in the London exhibition. Looking back to that first loan exhibition Mr. Bradstreet today told of the connection he had with it. He said he had just returned from London and was greatly taken by the Whistler vogue. When he was commissioned to hang the pictures, he decided on a room in honor of the master. He purchased a great quantity of yellow paint and covered the walls with it. He then devoted his attention to the floor which he tinted yellow and light brown. When completed he looked at his work with pleasure only to find that a long black stove pipe running the full length of the room disturbed the harmony. 'This could not be,' said Mr. Bradstreet. 'It ruined the whole setting. I proceeded to decorate the stovepipe in yellow. I painted it a hue calculated to blend with the general tone of the room and the visitors had many a laugh when they saw that yellow stovepipe.' Mr. Bradstreet to this day has the one original Whistler etching that adorned the walls of the room. Though it was the whole Whistler show, so to speak, it attracted much attention and today is one of the most valuable Whistlers in the world. It is a scene called 'Venetian Doorways.'" "First Art Show Recalled Today," Minneapolis Journal, 11 January 1911. Additionally, Oscar Wilde lectured on the English Renaissance in both Minneapolis (at the Academy of Music on 15 March 1882) and St. Paul (at the Opera House on 16 March 1882) while on his famous lecture tour of the United States. No records have surfaced, however, documenting any meetings between Wilde and Bradstreet. John T. Flanagan, "Oscar Wilde's Twin City Appearances," Minnesota History 17, no. 1 (1936): 38-48. 37. Edgar, "John Scott Bradstreet," 215-16. 38. Memorial Statement, Bulletin of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts 3, no. 10 (October 1914): 25. 39. Details regarding the fire and the subsequent arrest of a young man in Bradstreet's employ are found in the following articles: "A Syndicate Blaze," Minneapolis Journal, 7 June 1893; "A Youthful Firebug: John Singleton Confesses Having Set the Bradstreet-Thurber Fire," Minneapolis Journal, 12 July 1893; "Told a Cellmate," Minneapolis Journal, 13 July 1893. 40. "Mr. Bradstreet Takes a Partner," Minneapolis Journal, 28 September 1901; "Town Talk," Minneapolis Journal, 16 October 1901. 41. "J.S. Bradstreet & Co. have taken the Faries property, Fourth Avenue S and Seventh Street for ten years and will establish their business there. Improvements to cost from $8,000 to $10,000 are contemplated and under way. J.L. Robinson, the contractor, is already engaged in putting up a brick building on the rear of the inside lots, and the house will be remodeled on Mr. Bradstreet's general plan for the corner, which is understood to be unique, involving a Japanese garden. The corner measures 182 feet on Seventh Street and 165 on the avenue, affording an excellent opportunity for effective landscaping. Part of the new building will be two stories in height. This will give opportunity in the second story room for exhibitions and art meetings." "Bradstreet's New Move," Minneapolis Journal, 15 October 1903. 42. Inspector of Buildings Card for 325-29 South Seventh Street (18 September 1888—27 January 1954). Minneapolis Public Library Special Collections. 43. "Fine Collection in its New Home," Minneapolis Journal, 30 January 1904. 44. The International Studio 23 (1904): 335; "The Crafthouse of John S. Bradstreet & Company: One of the Beauty Spots of Minneapolis," Minneapolis Journal, 31 March 1910, sec. 2. 45. Gustave Stickley, "A Garden Fountain," The Craftsman 7 (October 1904): 69-75. 46. Richards, Skylight Club. 47. Hewitt, "John S. Bradstreet," 424-27. 48. Keith Clark, "The Bradstreet Crafthouse," The House Beautiful 16 (June 1904): 21-23. 49. John S. Bradstreet & Co., Promotional Booklet. 50. Clark, "The Bradstreet Crafthouse," 21-23. 51. Ibid. 52. Richards, Skylight Club. 53. The term sackinto appears in the caption of a period photograph of the Crafthouse interior, but research has revealed nothing of the nature of the cloth to which this term refers. 54. This dull yellow color appears to have been a special favorite of Bradstreet throughout much of his career. As early as 1883 he expressed an appreciation for the evocativeness of the tone in his admiration of its use by Whistler in the famous White and Yellow exhibit which Bradstreet attended in London. "First Art Show Recalled Today." 55. Clark, "The Bradstreet Crafthouse," 21-23. 56. Lesley, "John Scott Bradstreet: Minneapolis Interior Decorator," (Notes for master's thesis), Note # 17: from conversation with William Eckert 57. A more complete notion of the range of items the Crafthouse contained is given in an excerpt from a promotional booklet: "The lover of the quaint and beautiful finds the salesrooms most interesting. He will see displayed many articles which are specimens of fine skill in handicraft and full of historic interest: Florentine marbles, odd chairs, tables and chests from Italy; oak cabinets, old and artistic furniture and bric-a-brac from Germany; fine Gobelin, Brussels and Aubuson tapestries and ancient furniture from France, some pieces belonging to the period of the Empire, others of the times of the Louis'; Scotch, German and Oriental rugs of exquisite workmanship which can be had to order, made after special designs; Japanese bronzes, embroideries, prints and carvings." John S. Bradstreet & Co., Promotional Booklet. 58. Clark, "The Bradstreet Crafthouse," 21-23. 59. John S. Bradstreet & Co., Promotional Booklet. 60. Ibid. 61. Hewitt, "John S. Bradstreet," 424-27. 62. Lesley, "John Scott Bradstreet: Minneapolis Interior Decorator," (Notes for master's thesis), Note # 17: from conversation with William Eckert. 63. Richards, Skylight Club. 64. Lesley, "John Scott Bradstreet: Minneapolis Interior Decorator," (Notes for master's thesis), Note # 14. 65. Saylor, "Japanese Garden in America," 481-84. Descriptions of the garden also taken from: Hewitt, "John S. Bradstreet," 424-27, and Stickley, "A Garden Fountain," 69-75. 66. Stickley, "A Garden Fountain," 69-75. 67. Bradstreet made this comparison himself in a promotional booklet for the Crafthouse. John S. Bradstreet & Co., Promotional Booklet. 68. Ibid. 69. Richards, Skylight Club. 70. Lesley, "John Scott Bradstreet: Minneapolis Interior Decorator," (Notes for master's thesis), Notes # 1 and 13: from conversation with William Eckert. 71. Kevin P. Rodel, Jon Binzen, and Erica Sanders-Foege, eds., Arts and Crafts Furniture: Classic to Contemporary (Newton: Taunton Press, 2003), 193. 72. In an article published 13 July 1903, Bradstreet indicated that his first trip to Japan occurred fourteen years prior, placing the most likely date of his first travels in the country to the year 1889. "Japan of To-day: Impressions of John S. Bradstreet Just Back from Trip thru the Empire," Minneapolis Journal, 13 July 1903. 73. Kevin P. Rodel, Jon Binzen, and Erica Sanders-Foege, ed., Arts and Crafts Furniture: Classic to Contemporary. (Newton: Taunton Press, 2003), 193.