The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Eclecticism has served as a defining characteristic of William Merritt Chase’s (1849–1916) oeuvre, studio décor, and artistic process since he launched his career during the concluding decades of the nineteenth century in New York. Critics and commentators have used the term liberally to describe Chase’s versatility exemplified by his forays into multiple genres, his diverse stylistic borrowings from old masters and his European contemporaries, and his heterogeneous studio collection of Asian and European objects from various historical periods. The artist encouraged his students to follow his preferred eclectic method, instructing them: “Be in an absorbent frame of mind. Take the best from everything.”[1] He also felt the need to defend against claims that the eclectic approach lacked creativity and innovation, declaring, “I have been a thief, I have stolen all my life—I have never been so foolish and foolhardy as to refrain from stealing for fear I should be considered as not ‘original.’ Originality is found in the greatest composite which you can bring together.”[2] Chase believed his originality depended on assembling what he deemed “the best from everything.” His eclecticism has had varying, even surprisingly contrasting, implications for the way in which he was characterized as an artist: in the 1880s, at the beginning of his career, his combinatorial practice led to his categorization as a painter strongly influenced by European aesthetics, whereas by 1910, it caused critics to define him as “a quintessential American artist.”[3]

Note: Use the tools available on your device to move and zoom.

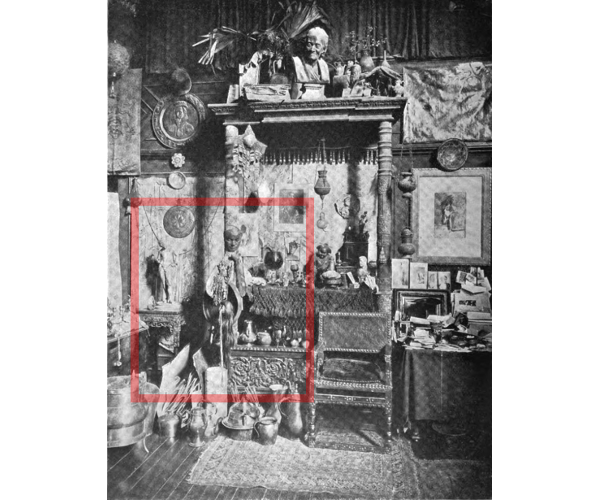

Fig. 1, William Merritt Chase, Studio Interior, ca. 1882. Oil on canvas, 28 1/16 x 40 1/8 in. (71.2 x 101.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mrs. Carll H. de Silver in memory of her husband, 13.50. Courtesy of Brooklyn Museum.

Fig. 1a, Detail of objects on the wall. ↩

Fig. 1b, Detail of the two paintings hanging on the wall above the female figure. ↩

Fig. 1c, Detail of two sculptures on the top of the Renaissance-style carved cabinet. ↩

While eclecticism is a frequently used stylistic appellation in the historiography of Chase’s work, it has not been treated analytically or situated historically. To correct this lacuna in the scholarship, this article turns to a specific subject in Chase’s oeuvre: his atelier.[4] His depictions of his studio not only represent his eclectic collection but also, I contend, visualize the mechanics of his eclectic artistic process. Focusing on two exemplary paintings of his Tenth Street Studio in New York from the early 1880s: Studio Interior (fig. 1) and The Connoisseur—Studio Corner (Studio Interior) (fig. 2), this article offers a detailed examination of Chase’s eclectic practice. First, it proposes that he reordered components of existing subject matter to invent a type of interior imagery—what I call an “artful interior.”[5] Second, it explores the organizational and pictorial strategies Chase used to intensify the variable yet unifying characteristics of eclecticism. In doing so, I study both the contents of the paintings and their arrangement, turning to helpful paradigms, such as the semi-lattice structure, to explain the dynamically ordered display of objects.[6] My argument shows how eclecticism as artistic process and pictorial effect liberated Chase from conventions, enabling him to both foreground his individuality and depart from the prescribed interior decoration of the then-dominant Aesthetic Movement. Chase’s artful interiors ultimately accomplish his aim of arriving at originality through selection rather than invention.

Before turning to Chase’s paintings, it is necessary to establish a working definition and the historical context of eclecticism. The term is more than just a synonym for diversity, though in its shallowest sense the two often are conflated; it names a process or practice of selecting “what are considered the best elements of all systems” to form a new one.[7] As suggested by this definition, eclecticism depends on informed choices, and by the late nineteenth century, discussions of eclecticism in popular magazines and trade publications emphasized the difficult and serious study required to achieve a harmony of diverse elements in architecture as well as in the fine and decorative arts.[8] As the literary historian Christine Bolus-Reichert explains, eclecticism in nineteenth-century artistic culture had “to get beyond a damaging, naïve eclecticism,” which was linked to pure imitation and mere reproduction of historical styles, by pursuing “a more rigorous eclecticism” that expressed thoughtful diversity, not just a jumble of sources.[9] Its success depended on the judgment of a knowledgeable individual who could create a meaningful, original assemblage of elements, and on a discriminatory rather than a passive process of selection, based on clear intention and reason instead of chance and intuition. Late nineteenth-century interior decorating manuals called for meaningful approaches to eclecticism in décor, prescribing that objects must be arranged uniquely in the service of the individual.[10] Otherwise, the final ensemble risked seeming too derivative, devolving into the “dubious eclecticism” decried by Edith Wharton (1862–1937) and Ogden Codman (1863–1951) in The Decoration of Houses, published in 1897.[11] The variety found in an unsuccessful eclectic arrangement was seen as a mere compromise, lacking a definite position, and pluralistic to the point of causing confusion.[12]

During the nineteenth century, in the United States as in Europe, eclecticism took hold as a conceptual approach in numerous aspects of culture. In the first half of the century, it became a dominant tendency in juste milieu French painting before spreading throughout Europe and to the United States by midcentury. Informed by Victor Cousin’s (1792–1867) philosophy of eclecticism, French artists, such as Thomas Couture (1815–79), developed an “eclectic vision,” promoting it in their art and teaching.[13] As Albert Boime contends in his comprehensive study of eclecticism in painting, Thomas Couture and the Eclectic Vision:

Above all, Couture’s reputation as an eclectic endeared him to the American sensibility. They knew him as a painter who transformed the old “ideal” with romantic ardour and rich colour, and who found in the events of everyday life the material for an elevated view of existence. They found this combination of qualities irresistible for it seemed to reconcile the conservatism of their parents with the eager throb of younger life.[14]

Nineteenth-century critics and commentators, including James Jackson Jarves (1818–88), deemed eclecticism particularly suitable for American art and architecture, which lacked a well-established canon and embraced a cosmopolitan approach.[15] As one architectural critic stated: “Our exceptional position as Americans, the mixed nationalities and sympathy of our people, and our free intercourse with many foreign nations, bring before us elements of design from all quarters, and at the same time increase the difficulty of our selecting any distinct style to which we shall devote ourselves.”[16] The outcome of this sensibility was a profusion of “mixed” art and architecture that combined seemingly disparate elements. As historian T. J. Jackson Lears observes, “In the post-Civil War American city, eclectic ornament bedecked nearly everything in sight, from public buildings to the most ordinary objects in private households.”[17] By the late nineteenth century, eclecticism served as a dominant aesthetic in American visual culture.

While some may think of eclecticism solely in relation to art and architecture in nineteenth-century America, it informed other aspects of culture such as secular and religious education. Late nineteenth-century education reformers argued that undergraduates should not specialize but gain an overview of many disciplines. For example, the American philosopher John Fiske (1842–1901) called for undergraduate students at Harvard University “to obtain a knowledge of all” by pursuing “a catholic education,” arguing that “our aim is not to encourage crude smattering or vain sciolism, but to enable the student to approach his own special subject in light thrown upon it by widely different subjects, and with the varied mental discipline which no single study is competent to furnish.”[18] For Fiske, this unspecialized, not always practical, approach to undergraduate education had to be both “varied and harmonious.”[19] Connections had to be made between the areas of study and their methods of approach; diversity for diversity’s sake was indulgent. Progressive religious reformers, as comparative-religion scholar Emily Mace explains, compiled lessons, anthologies of scriptures, and instructional pamphlets in the hope “that familiarity with the world’s religions as presented in liturgy and literacy could ameliorate these social ills by lessening prejudice and promoting universal religious sentiments and ideas.”[20] Both religious reformers and educators recognized the eclectic method’s suitability for accommodating far-ranging curiosity and for systematizing and totalizing a wide range of ideas and practices.

The influence of eclecticism was present in the writing and publishing of literature as well, reinforced by the use of “eclectic” in the titles of publications. Literary magazines, including the Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art (New York, 1844–98), and educational textbooks like the McGuffey’s Eclectic Readers, cultivated “an aesthetic of eclecticism,” compiling and printing a wide array of national and international texts written in diverse styles.[21]

The prevalence of eclecticism during the nineteenth century may be explicated in part by the loss of authority and the crisis of values associated with this period.[22] Widespread social changes caused by industrialization and urbanization, among other forces, led to the collapse of long-standing cultural beliefs. Rather than replacing existing hierarchies or belief systems with similar ones, this more pragmatic approach allowed for a range of ideas or approaches to co-exist without prioritizing one over another. In theory, this eclectic method was shaped by tolerance, openness, and freedom of thought, concepts linked to democracy and the aspirational cosmopolitanism of the time. During the nineteenth century, members of the middle and upper classes began to see themselves as citizens of the world and to acknowledge its richness and diversity, even if that meant only so-called armchair exploration, collecting artifacts at nearby shops or antique markets, or going to World’s Fairs rather than having direct encounters with people in their homelands.

While eclecticism played a role in acknowledging and celebrating diversity, it threatened to diminish differences as well. From our current perspective, it did not escape the politics of the time and involved what we now regard as imperialist behavior dependent on Western attitudes of cultural superiority. As cultures from around the world became available to Americans and Europeans through travel and immigration, artists freely appropriated them, often making cultural comparisons at the expense of acknowledging significant differences. Americans and Europeans also forced non-Western cultures and ideas into Western paradigms. For example, in her discussion of religious texts, Mace points to “the compilers’ use of categories unique to Western understandings of religion.”[23] Similarly, Chase and his American and European contemporaries transformed objects, such as ceramic plates and fans, with particular, sometimes ritual, functions, into wall decorations. Stripped of their context, these things lost their original function and contributed an aesthetic of cultural diversity to the eclectic ensemble.

Chase as an Ideal Eclectic

For Chase, an artist’s success relied on two essential skills: (1) the ability to discriminate the “best of everything” from an almost infinite range of cultures; and (2) the expertise to create a composite from the selected sources. Thus, a well-rounded education that enabled informed judgments and an understanding of the aesthetic of eclecticism played an essential role in Chase’s idea of the artistic process. In addition, responding to existing sources meant more than just copying them; Chase believed in the importance of retaining a sense of self and adapting the past to the present. He told his students to “take the best from everything” yet, as he elaborated in a lecture he gave to a group of New York art students at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in January 1916, after selecting an artwork in the museum, “Drink it in to the fullest. Then go to your studio, take your picture with you in your mind’s eye, and imitate it, and exist in it.”[24]

Much of what Chase asserted in his instructional lectures and essays relates to, even reiterates, statements by earlier supporters of eclecticism in art, most notably the British painter Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–92). In his Discourses delivered before the Royal Academy from 1769 to 1790, Reynolds encouraged artists to study a range of “authentic models” from history, acquiring “that idea of excellence which is the result of the accumulated experience of past ages” to shape the art of the future and “to avoid the narrowness and poverty of conception which attends a bigoted admiration of a single master.”[25] Reynolds warned against “general copying,” stating that it can lead the student “into the dangerous habit of imitating without selecting, and of labouring without any determinate object; as it requires no effort of the mind, he sleeps over his work; and those powers of invention and composition which ought particularly to be called out and put in action lie torpid, and lose their energy for want of exercise.”[26] To become a master, the student first must learn to be a critic and scholar who can decipher and select the best qualities from a variety of artworks. Experienced artists, not just students, should continue to study and imitate the masters, because, as Reynolds clarified:

By imitation only, variety, and even originality of invention, is produced. I will go further; even genius, at least what generally is so called, is the child of imitation. . . .

Invention is one of the great marks of genius; but if we consult experience we shall find that it is by being conversant with the inventions of others that we learn to invent, as by reading the thoughts of others we learn to think.[27]

His call for artists to “invent” by consulting, but not imitating exactly, a variety of well-selected “authentic models” echoes in Chase’s instructions to his students over a century later.

During the nineteenth century, Chase had the credentials and experience deemed suitable for the sort of decision-making required by eclecticism. As reviews and discussions of his artwork and studio suggest, his contemporaries considered him an artist with a sophisticated, cosmopolitan taste, cultivated during his study at the Royal Academy in Munich (1872–78) and subsequent travel in Europe.[28] His experience abroad afforded him the expertise for choosing and arranging in an eclectic manner fine and decorative arts in his atelier. Even before Chase finished moving into his Tenth Street studio in 1879, it caught the particular attention of the press. In an 1879 article in the Art Journal, the critic John Moran identified it as a “characteristic studio-interior” and expressed admiration for its harmonious yet heterogeneous décor, commenting, “After a time one’s eye wanders about, now lighting on this object, now on that, till the wonder is excited how constituents so multifarious and seemingly incongruous can make up such a delightful ensemble.”[29] Chase embraced his role as a cultural leader and tastemaker: in 1881, following the precedent of European artists, most notably the Viennese painter Hans Makart (1840–84), he opened his Tenth Street studio to the public for weekly receptions. As a result, Chase gained notoriety for the eclectic ensembles he created in his actual atelier as well as those he included in his representations of it.[30]

The Artful Interiors and Their Eclecticism

To a greater degree than his actual studio, his painted studio interiors express the mechanics of Chase’s eclecticism and its impact on his artmaking. They begin with a process of selection similar to that involved in eclecticism itself. Chase had to choose what objects and which area of the studio to depict. Studio Interior and The Connoisseur—Studio Corner represent different spaces in the atelier, distinct compositional arrangements (frieze-like versus “cozy corner”) as well as varying combinations of objects.[31] As a partial inventory of the collection displayed in Studio Interior demonstrates, the sampling of objects evokes the diversity of things typically associated with an eclectic collection. On the left side of the painting Studio Interior appear two prominent objects, a half-length portrait painting of an unidentified man in an Old Master style with a dark background, and a Japanese brass basin with a potted palm placed on a wrought iron plant stand with ribbon and scrollwork design. The basin is placed in front of a yellow Chinese silk portiere or door covering with a floral pattern. In the central section of the scene, hanging on the wall on a Middle Eastern, probably Turkish, carpet, starting at the top, are a shield (only half of which is visible), a framed Japanese print or a watercolor accompanied by Japanese fans, a Spanish mandolin arranged together with a sword and a woven bag with a fringe, a dramatically lit winter landscape painting, and a reproduction of Malle Babbe by the seventeenth-century Dutch artist Frans Hals (1580–1666). Below the framed artworks stands an eighteenth-century French wooden bench, on which a woman in a historical American costume from the early nineteenth century sits next to a polished brass salver resting on a red, probably Japanese, textile. On the floor in front of the woman is another carpet, of either Chinese or Middle Eastern origin, and an array of books, the largest of which she studies. To the right of this central area appears a Renaissance-style carved, dark wood cabinet. This piece of furniture is decorated with a selection of bric-a-brac, notably, on the top, a galleon or merchant ship model, a Neoclassical sculptural head of a man, and an Egyptian figurine, and on the shelf below, an assortment of glassware and ceramic dishes, a print, a red-glazed vase filled with paint brushes, and two vases with flowers. Adjacent to the cabinet and hanging on the wall, starting from the top, are a Hispano-Moresque lusterware dish, below which appears an artwork with a wood frame and cream-colored mat, and a hanging dark glass wine jug. On the floor beneath is a Renaissance-style chair with carved arms and legs, upholstered with blue velvet and edged with tassels, on which a textile, a painting, and works on paper casually rest. This only partial inventory reveals the breadth of Chase’s collection, which by 1896 consisted of over 2,000 objects from a wide variety of periods and cultures, all assembled in his large, two-story space in the Tenth Street Studio building in New York City.[32] A descriptive survey of The Connoisseur—Studio Corner would yield a similarly diverse albeit different group of things.

The atelier scenes, however, do more than merely represent Chase’s eclectic approach to collecting; their very subject matter results from an eclectic process. Chase combined elements from several well-known artistic subjects to invent what I identify as a new type of imagery that flourished from the early 1880s into the 1920s: “the artful interior.” The term “artful” has several connotations pertaining to the self-conscious evocation of “art” in this kind of picture: it describes the fine and decorative art that fills the space; it evokes the artifice of the composition—most often a studio setting made to look like an aesthetically pleasing domestic room; and it alludes to the skillful rendering and manipulation of the subject by the artist. My adoption of the artful interior term refers to a type of visual representation derived from Marilynn Johnson’s use of the phrase in her discussion of Aesthetic period interior decoration. In particular, she claims that the artfulness of this type of room, exemplified in her discussion by William H. Vanderbilt’s (1821–85) library (fig. 3), results in “striking oppositions: exuberant and restrained, tasteful and tacky, moral and meaningless, serious and playful.”[33] Like the Aesthetic rooms discussed by Johnson, Chase’s artful interiors display contrasts—though not the same ones identified by Johnson—which, I argue, showcase his aesthetic of eclecticism.

Chase’s artful interior scenes emerged under specific conditions in the nineteenth century when artist’s studios became prototypes for domestic interiors, and when making something tasteful and modern meant making it eclectic and by extension individual.[34] Ironically, Chase constructed his au courant artful interior compositions by synthesizing elements from past genres and works of art. As will be shown, his works acknowledge a debt to a variety of existing subjects.

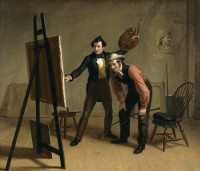

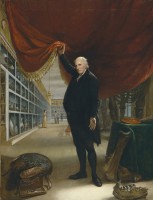

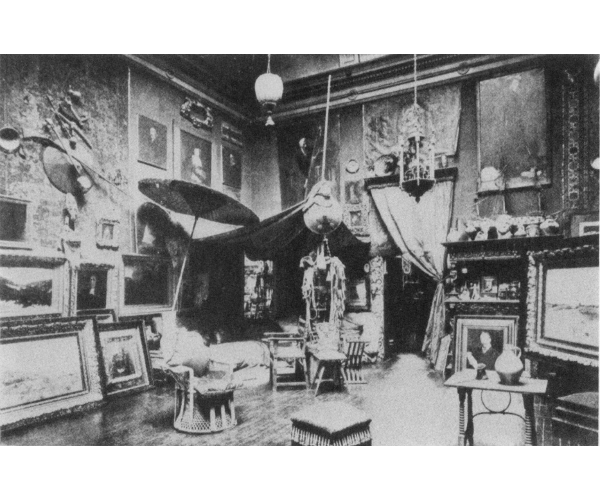

Studio Interior and The Connoisseur—Studio Corner, perhaps most obviously, both borrow from and challenge the genre of the artist’s atelier. The settings in these paintings—a wall in the outer room and the southwest corner of the inner area of Chase’s Tenth Street studio, respectively—can be identified as a studio by the titles and as Chase’s workspace in particular by comparing the artworks with photographs (figs. 4, 5, 6, 7). While the paintings do not exactly reproduce the photographs, they do include some of the arrangements of objects: the ensemble in the central section of Studio Interior appears in fig. 4 and again in fig. 5 on the left; the door with the portiere along with the Renaissance-style chest with bric-a-brac in Studio Interior can be seen in fig. 5 on the right; the “cozy corner” with the Narcissus sculpture from The Connoisseur—Studio Corner can be found in fig. 6 on the right; and part of the collection from The Connoisseur—Studio Corner, including the Narcissus sculpture, the face mask, the shrunken head, and the Renaissance cassone is visible in fig. 7 on the left as indicated by the red box. The paintings also include a rather subtle, easily overlooked reference to artmaking tools: paintbrushes appear in the red vase on the shelf of the Renaissance-style, carved wood cabinet in Studio Interior and in the brown and green vases on either side of the seated female figure in The Connoisseur—Studio Corner. These two images, however, depart from convention by eliminating the portrayal of the artist, whether a self-portrait or the depiction of another artist, engaged in aesthetic production. Chase did not portray himself at his easel or showing his work to an admirer and potential patron, as William Sidney Mount (1807–68) did in The Painter’s Triumph (fig. 8); engaged with a model or muse, as in Alfred Stevens’s (1823–1906) The Painter and His Model (fig. 9); or showing off his collection and his palette, as Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) did in his self-portrait, Artist in His Museum (fig. 10). In place of himself or another artist, Chase portrayed a female figure who does not create art but looks through images. Her act of looking likens these paintings to images of connoisseurs.

In conventional depictions of connoisseurs from the nineteenth century, men alone or in small groups examine prints, drawings, paintings, or sculpture. The Spanish painter Mariano Fortuny (1838–74), whose work Chase greatly admired, became known for his representations of this subject.[35] Chase would have been familiar with Fortuny’s paintings, such as Antiquaries (fig. 11), in which two men in eighteenth-century dress in the left middleground study a portfolio of engravings while a third man in the right background holds an additional portfolio and looks down at a group of images on the table before him.[36] The three antiquaries appear in a room filled with an eclectic collection, ranging from a set of Medieval-era Japanese armor to a Chinese vase to a classical-style sculpture.[37] The similarities in subject and compositional arrangement of Fortuny’s and Chase’s paintings reveal the impact that the Spanish painter had on the younger artist’s artful interiors. They both depict figures, located in the middleground of the picture, absorbed in looking at art in the midst of a room replete with art and decorative objects. In The Connoisseur—Studio Corner, Chase even seems to have borrowed both Fortuny’s depiction of a pile of images spread out on the floor beside the individual sorting through the portfolio, and the representation of a transitional object in the foreground that both separates viewers from and invites them into the scene. Not surprisingly, Oliver Larkin in his celebrated survey of American art and culture, Art and Life in America (first published in 1949), referred to Chase as “the Fortuny of the Tenth Street Studio.”[38]

If Fortuny’s paintings served as a source for the artful interiors, Chase did not imitate them slavishly. He replaced the three male connoisseurs with a solitary female one. This alteration enabled him to construct the kind of contemplative environment for looking at art he preferred by eliminating the potential for social engagement that he decried as a distraction, stating in his teachings that “it is better not to say much at all. Large discussion is needless, useless, harmful.”[39] More significantly, the choice of a woman as a connoisseur modernized Fortuny’s imagery. Chase’s female connoisseur not only departs from Fortuny’s work but also does not conform to stereotypical portrayals of women in genre scenes with interior settings: she does not perform domestic activities, such as childrearing, cooking, sewing, or socializing, as seen in paintings such as Lilly Martin Spencer’s (1822–1902) Kiss Me and You’ll Kiss the ‘Lasses (fig. 12). Rather, she embodied Chase’s experience as an artist and an art teacher as well as suggesting his awareness of the “feminization” of art consumption during this period.

Beginning around the 1870s, women increasingly played the role of art patrons, admirers, and cultural preservers. Significantly, they were tasked with ensuring the cultivation and aesthetic refinement of their families and society at large. Chase observed first hand this shift away from the tradition of elite, male art education and patronage: he had many female students and studio visitors.[40] In fact, in 1886 he married one of his studio visitors, Alice Gerson (1866–1927), who later modeled for The Connoisseur—Studio Corner.[41] In contrast to some of his contemporaries, such as Charles Courtney Curran (1861–1942) in his painting Fair Critics (fig. 13), Chase did not represent the woman as a passive model or a temporary visitor in a coat and hat, he gave her the more active role of art appreciator at home in the studio.

While Studio Interior represents the female figure in a historical costume, like the men in Fortuny’s paintings, as Chase developed this imagery, he focused on the depiction of a fashionably dressed, understood as modern, woman.[42] In his selection of clothing and accessories for The Connoisseur—Studio Corner, he abandoned the costume from the past featured in The Studio Interior—an evening dress and bonnet with an ostrich plume, probably from the 1820s, and mittens from the 1830s—and insisted on her presentness: she wears the type of dress appropriate for relaxing at home—a rose tea gown with a striped pattern and three-quarter length, banded and ruffled sleeves; and a white, ruffed Medici-type high collar.[43] The tea gown along with the hairstyle, a chignon at the back of the neck, identifies her as fashionable and aware of the sophisticated, late nineteenth-century taste for seemingly natural, simple Aesthetic-style attire. By the early 1880s, as Sylvia Yount asserts, Chase was among the leading New York tastemakers who helped transform the phenomenon of Aesthetic production and consumption into a “‘craze,’ signifying cultural sophistication.”[44] While the dress located the female figure in the then-present day, it simultaneously linked her to British and French traditions of representing women in loose-fitting gowns, as seen in the work of James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) and in that of the artists he admired from Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) to Édouard Manet (1832–83) and the Pre-Raphaelites (fig. 14).[45]

By the time Chase painted his artful interiors, a number of European artists already specialized in images of female figures in studios or elaborately decorated interiors. According to the art historian Barbara Gallati, Chase’s shift to an up-to-date subject—rendered in a lighter palette than his earlier paintings influenced by the dark, Old Master aesthetic he learned in Munich—may be the result of a visit he paid to the Belgian painter Alfred Stevens in the summer of 1881.[46] As a comparison of Stevens’s and Chase’s paintings reveals, the latter artist drew inspiration from the former’s interior scenes with female figures. For example, Chase’s The Connoisseur—Studio Corner has much in common with Stevens’s La Psyché (My Studio) (fig. 15). Both represent a fashionably dressed young woman in a corner of the studio with paintings hanging on the wall and stacked against it, a portfolio full of images, and Japanese objects (a fan and a kimono in Chase’s painting and a portfolio of prints on the chair in that of Stevens). Yet, significantly, Chase’s female figure appears seated and absorbed in looking at the image on the sheet in her hands whereas Stevens’s young woman, likely a model, is standing and peering coyly around the edge of the mirror. Chase seems to have adopted Stevens’s modern woman in the studio but not the often-sentimental, romantic narrative that accompanies her.

Another artist who influenced Chase’s artful interior compositions is the Hungarian painter Mihály Munkácsy (1844–1900), who frequently portrayed family scenes in the elaborately decorated settings of his studio or a domestic space. According to one of Chase’s students, Edwin W. Deming (1860–1942), Chase was with Munkácsy when he painted In the Studio (1876; Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest), a scene of an artist looking with a woman (his wife) at a painting on the easel, behind which appears a young boy (their son) in overalls.[47] In another related painting, Paris, Interior (fig. 16), Munkácsy portrayed a mother seated at a table reading and a child playing on the floor behind her with a small dog in an eclectically decorated interior that resembles those in Chase’s paintings.[48]

As seen in Chase’s artful interior imagery, the treatment of the objects as a collection, and their arrangement in a frieze-like or salon-style manner along a wall or in a corner, shares an affinity not only with the aforementioned paintings of studio and domestic interiors, but also more broadly with the Dutch “cabinet of curiosity” or “gallery picture,” exemplified by David Teniers the Younger’s (1610–90) The Art Collection of Archduke Leopold William in Brussels (fig. 17). This genre of painting that flourished in seventeenth-century Antwerp was revived in Europe and the United States in the nineteenth century with the growth of private and public collections. Chase, who shared the nineteenth century’s renewed interest in seventeenth-century Dutch painting, arguably found such pictures useful prototypes for his artful interiors since they visualize so explicitly the artistic impulse he embraced in their heterogeneous collections of objects assembled in intentionally contrasting ways—formally on the wall and casually leaning on chairs or piled on the floor.[49]

As Victor Stoichita’s analysis of the “gallery picture” reveals, seventeenth-century artists pursued both documentary and symbolic approaches to “the cabinet of curiosity” or “gallery picture.”[50] Documentary images, such as David Teniers the Younger’s The Art Collection of Archduke Leopold William in Brussels (fig. 17), acted like catalogs, reproducing each painting in a particular collection in an exacting manner, and served as a means to share the collection with friends, relations, and colleagues; other paintings, like Hieronymous Francken II (1578–1623) and Jan Brueghel the Elder’s (1568–1625) The Archdukes Albert and Isabella Visiting the Collection of Pierre Roose (fig. 18), record visits to collections by royalty or the elite, portraying historical figures in the foreground. In contrast, symbolic representations, such as Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens’s (1577–1640) Allegory of Sight (fig. 19), function allegorically, arranging artworks and decorative objects to convey a specific iconographic message. The Brueghel and Rubens example, part of a series dedicated to the five senses, represents a grand room crowded with a collection of curiosities that includes coins, exotic animals, a globe, medals, and scientific instruments along with paintings, prints, sculptures, and tapestries. It incorporates repeated allusions to sight and its opposite, blindness: first, in the center appears a seated semi-nude woman (Juno Optica, goddess of sight) looking at a painting resting on the table before her and held up by a putto; second, the painting-within-the-painting that Juno Optica examines portrays Christ restoring the blind man’s sight; third, other objects relating to human vision and its enhancement, such as a magnifying glass, a telescope, and a pair of glasses, appear nearby; and finally, there are additional references to blindness, most notably, a painting of the parable of the blind, in the style of Brueghel, leaning against the center of the back wall, and partially hidden by a Venetian-style portrait (fig. 20). Together, these pictures-within-pictures and objects serve as a meditation on sight, blindness, and the acquisition of knowledge.[51]

Chase’s artful interiors combine characteristics of the documentary and symbolic impulses of his seventeenth-century Dutch progenitors. They have enough detail to be identified as Chase’s studio when compared to photographs of the actual spaces, but they do not include exacting and precise representations of the atelier’s contents (compare fig. 1 to figs. 4, 5; and fig. 2 to figs. 6, 7). In addition, the objects appear in sequences and groupings that, as will be argued, inform the viewer about Chase’s eclectic taste and the historical development of art more broadly, but they do not work together like the collection in Brueghel and Rubens’s painting to construct a well-established allegory or narrative.

To arrive at his vision of the artful interior, Chase engaged in an eclectic process, taking what he deemed the best from existing pictorial imagery. He combined aspects of the “gallery picture,” the artist’s studio scene, the connoisseur with his collection, and the fashionable female figure in an elaborately decorated studio or domestic interior. He borrowed compositional arrangements and particular pictorial devices as well as activities and poses from paintings dating back to the seventeenth century and incorporated them into the depiction of his own studio space with his nineteenth-century collection and sitters. He retained the contemplative art appreciator concentrating on the artwork before him from Fortuny’s paintings of connoisseurs, and the woman in a fashionable dress from Munkácsy’s, Stevens’s, and Whistler’s interior imagery. However, gone are the romantic and allegorical narratives, the historical settings and male figures, and the self-portraits and overt signs of aesthetic production. Drawing on aspects of existing categories and genres, Chase combined them to invent his own approach in his artful interiors.

The artful interior’s composite character connects it to the widespread phenomenon of eclecticism as it flourished during the nineteenth century. As previously mentioned, the popularity of eclecticism in art and culture during the 1880s and 1890s occurred at a time when older systems and hierarchies were questioned and overthrown. In the art world, this breakdown of convention manifested itself in the collapse of the classical system of genres, which were arranged according to their relative importance with history painting as the most significant and still life as the least noteworthy. The disintegration of this hierarchy encouraged artists like Chase to develop new subjects by synthesizing what they regarded as the best elements from established ones. Chase did not simply copy existing imagery but instead selected aspects of it to assemble his own subject of the artful interior, thereby laying claim to originality.

Chase’s Studio Arrangements

Eclecticism freed Chase from having to conform to prescribed ideas about subject matter as well as artistic style. It enabled him to acknowledge his debt to the past without being bound to only one tradition. Chase’s ensembles escape the look of a formulaic historical style, such as Gothic Revival or Neoclassic. They resemble the approach of late nineteenth-century architects, who acknowledged the past without slavishly adhering to it. As the architectural historian Richard Longstreth explains:

Eclectic diversity was seen as a means of liberating architecture from a deterministic use of the past while enabling it to be sensitively adjusted to the varied requirements of the present. It provided ways to expand the possibilities of creative design without abandoning ties to tradition. It offered a vehicle for achieving an eventual synthesis, but one that would never possess the characteristics of historical style. Diverse expression was not only the way of the present but also that of the future.[52]

Similar to American architects from the 1880s to the 1930s, among other eclectics, Chase eschewed a nostalgic attitude toward the past. As Bolus-Reichert explicates, “The eclectic does not time-travel. She does not put herself into the past; rather, she brings the past forward.”[53] Trying to replicate a historical source means that you are “untrue to [your]self and to the present age.”[54] Chase shared this attitude, telling his students, “Learn as much as you can from a school. Then go off alone and work it out for yourself.”[55] Studying the past was a requirement, but Chase understood the importance of retaining one’s own identity as an artist when confronting it. Unlike an archaeologist or an archivist, he never attempted to recover a particular style or moment in time, instead drawing on multiple periods that comprise the intervening years between past and present, thereby embracing the cross-historical character of eclecticism.

Comprised of objects from ancient times to the nineteenth century, Chase’s ensembles break from conventional, often hierarchical, museological methods of organization. They neither consist of objects arranged by type or species in an orderly, predictable fashion, as in the taxidermy birds in side-by-side glass cases in Peale’s self-portrait (fig. 10), nor do the objects belong to the same period or decorative style as seen in Walter Gay’s (1856–1937) Louis XVI-style rooms (fig. 21). Rather, Chase’s arrangements consist of a miscellany of objects from different cultures and moments in time, visualizing the eclectic process itself. As Bolus-Reichert explains in her discussion of Victor Cousin’s approach to eclectic philosophy, “Eclecticism builds itself up from details, or partial views, to general ideas and the mastering vision.”[56] Like Cousin’s philosophy, Chase’s studio decoration was constructed from parts painted to look like they belong to a “mastering vision.”

A number of pictorial devices, including omission of detail, repetition of color and form, and overlapping of objects, encourage viewers at first glance to perceive the objects as a “mastering vision.” In Studio Interior, for example, Chase edited out details, such as the decoration on the Japanese fans and the identifying features in the pictures-within-the-pictures, to prevent the observer from concentrating on the individual objects at the expense of the whole. To further unify the image, Chase repeated rectilinear and circular elements along with the three dominant tones of red, yellow ocher, and blue throughout the scene, taking advantage of the tendency to search for resemblances when confronted with difference. Additionally, Chase used overlapping and shared backdrops to connect groupings of objects across the composition. What I call the Japanese and Spanish sets in Studio Interior illustrate this system of arrangement (fig. 1a ↩). In the central section of the painting on the upper portion of the wall are two groupings. Each appears to contain three objects: the one on the left includes a Japanese print or a watercolor under the frame of which are two Japanese fans positioned at contrasting angles; the one on the right includes a Spanish mandolin with pearl inlay, a sword that at first looks like a bow, and a woven bag with a fringe. These two sets of what the viewer might regard as sharply contrasting things from distinct cultures and periods are related to each other through two visual strategies: (1) each grouping has a similarly dynamic placement of three objects at acute angles; (2) more importantly, the groupings hang side by side on the same backdrop—a Middle Eastern carpet—which, in turn, unifies them. The carpet also connects them to the shield, only half of which is visible above them, while the fringe of the woven bag in the Spanish set associates them with the artworks below by draping over the frames. Moreover, the Japanese and Spanish sets are linked to the composition as a whole through additional visual analogies—the framed Japanese print or watercolor has a counterpart in size and shape in the painting hanging to the right of the carved wood cabinet; the fringe of the woven bag draping over the frames below it finds its equivalent in the textile draped over the richly upholstered blue chair at the far right (fig. 1).

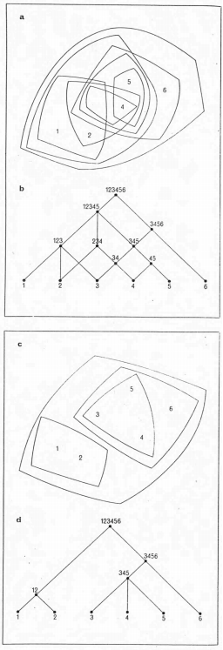

Fig. 22, Diagrams of semi-lattice structure (top) and tree structure (bottom). The semi-lattice is distinguished by its overlapping units. From Christopher Alexander, “A City Is Not a Tree,” reprint from Design no. 206 (February 1966): 5, isites.harvard.edu.

These visual analogies and the representational strategies, most notably the overlapping, that unify the whole painting resemble the organizing principles of a fluid, non-hierarchical semi-lattice structure. As elaborated by the architect Christopher Alexander in his analysis of city planning, the semi-lattice can best be understood in opposition to the tree structure.[57] While both organize sets of elements that appear to belong together, a tree structure does so with a hierarchy that has a starting point and a single path from one element or node to the next whereas the semi-lattice allows for overlapping sets so that its contents simultaneously belong in multiple groupings as well as to the entire ensemble (fig. 22). The semi-lattice provides a more complex, if not vital, structure than the tree and enables interaction among the parts of a collection instead of “extreme compartmentalization and the dissociation of internal elements.”[58] In Studio Interior, the Japanese and Spanish sets illustrate this organizational method. These objects appear as two discrete sets yet, for the eye, the carpet hanging on the wall behind them unifies them and creates a larger grouping in the center of the composition, which, in turn, forms one of the five vertical divisions along the wall.[59] Viewing Studio Interior as a shifting lattice of visual groupings does justice to the eclectic nature of the collection’s contents. In this light, the painting reveals itself as a dynamic constellation of objects; dynamic since the objects belong to multiple groups rather than appearing compartmentalized, or alternatively, contributing to an overarching allegory or narrative that insists on a predetermined order for understanding its meaning. Chase’s semi-lattice-like arrangements lack the predictable visual structure of Gay’s or Peale’s paintings, instead reinforcing the mercurial variability of eclecticism.

In lieu of resolving the discordance of variety, Chase almost antagonistically embraced difference: he rendered enough specific details so a sense of diversity is maintained but not allowed to collapse into a chaotic mess. Objects retain visual characteristics so they can be distinguished in the context of the collection. For example, in Studio Interior, the brass salver on the bench and the lusterware bowl in the upper right corner have similar round shapes, but they differ in color and treatment of their surfaces: their colors and light reflections evoke their unique materials, and their impressionistically depicted designs and surface patterns evoke their distinct cultural origins (European and Hispano-Moresque, respectively). Other parts of the composition, such as the bric-a-brac on the shelves of the Renaissance-style cabinet, risk falling into a shamble; however, each object has identifying characteristics that contribute to a careful arrangement. The balancing of the painting on the edge of order arguably excited his supporters yet overwhelmed, if not flummoxed, his critics, as will be addressed later.

Chase also varied his treatment of the objects, offering specific visual information about some and imprecisely rendering others, as though exposing through his depiction of the collection the selectivity required in the eclectic process itself. The dialing in and out of detail in the pictures-within-the-picture and the decorative objects recalls Fortuny’s method in his paintings and contrasts with the consistency of vision in the seventeenth-century Dutch “gallery pictures” and in Stevens’s images.[60] Painterly, impressionistic passages and adumbrations are employed conceptually as broad brushstrokes, bringing order where needed and marshalling the visually discrete into sets and passages of continuity, if not resemblance. These parts of the image effect a sense of higher reason, generalization, if not artistic intent.

While types of objects can be recognized, only a limited number can be identified exactly and, not surprisingly, the identifiable ones play a key role in Chase’s aesthetic. In Studio Interior, the face of the sitter in the portrait of a gentleman on the far left is indistinct, whereas the portrayal of a woman in the center, wearing a simple black dress with a white ruff around her neck and a matching white cap on her head—the kind of clothing worn in Haarlem in the 1630s—conveys enough visual cues to identify it as a reproduction of a historical artwork, Frans Hals’s Malle Babbe (fig. 23). Malle Babbe’s central placement in Studio Interior signifies the importance this image held for Chase, who claimed that it was “one of the finest of Hals’,” and evokes the prominent role that this Old Master’s work played in the younger painter’s artistic development.[61] Chase studied Hals’s paintings in Munich where he developed a technique of loose brushstrokes and daubs of color similar to that of the older artist. By depicting an artwork by another artist, he also paid homage to the tradition of the picture-within-the-picture.[62]

Chase approached the objects in The Connoisseur—Studio Corner in a similar way, providing moments of clarity in the midst of the ensemble: the works on paper in a pile on the floor consist of black, white, and cream strokes that do not crystallize into a recognizable image, whereas the sculpture of a contemplative young man on a pedestal behind the female figure has enough detail so that I was able to identify it during my research as a reproduction of a bronze original of Narcissus, discovered in Pompeii in 1862 (fig. 24).[63] By the 1880s, this sculpture had become a celebrated masterpiece, praised for its timeless beauty. It was mass-produced and widely distributed as a small-scale work suitable for domestic interiors.[64] In the context of Chase’s painting, the sculpture cements the artist’s up-to-date taste for ancient bronzes while suggesting his familiarity with the fashion for contributing to the aesthetic refinement of a room by installing sculpture on a pedestal in the corner. Furthermore, the central placement of Narcissus, who was identified with the self-absorbed Aesthete during the late nineteenth century, may evoke the concept of seeing the self in the world around oneself, in this case, in the artful interior and its objects.[65] Chase’s representation of a few, select reproductions of world-renowned artworks attest to his knowledge of a shared artistic tradition, thereby validating his role as an educated tastemaker.

By definition, eclecticism brings into close proximity what is usually conceived as different, remote, and not cognitively comingled. It, therefore, challenges the conventional notions of “propinquity” and “adjacency,” by bringing near elements that are distinct and well guarded from one another. In the artful interiors, Chase assembled and often paired objects that ordinarily would not appear together since they originated in vastly different periods and places and were made for various, sometimes contradictory, purposes. By grouping them, he established his own associations and links among them to promote a notion of culture as universal, heterogeneous, and cross-temporal.

To prevent a mismatched arrangement of his collection, Chase seems to have intentionally juxtaposed objects that have enough in common that they can be related to one another in at least one aspect. For example, in Studio Interior, Chase arranged in the center two artworks that belong to the tradition of painting, notably his primary medium: a wintery landscape by Chase or one of his contemporaries, most likely Adam (Brother Albert) Chmielowski (1845–1916), and a reproduction of Hals’s Malle Babbe (fig. 1b ↩).[66] Paired together, they allude to then-contemporary and past styles of painting, respectively, creating an opportunity for contrasting them: an outdoor scene with evocative, picturesque twilight effects rendered with loose brushstrokes in a manner associated with en plein air painting, and a potentially disturbing character study of an unattractive, cackling old crone from Haarlem with an owl on her shoulder, possibly referring to the Dutch proverb, “drunk as an owl.”[67] Aesthetically speaking, they do not work as a harmonious pair though Chase seems to have compensated visually for their lack of artistic unity by lining up perfectly, edge to edge, their dissimilar thin carved gilt and wide ebony frames. As a result, they appear to fit together on the wall despite their notable contrast in subject and style.

While this central pair presents opposing approaches to painting, another pair of objects exemplifies varying styles of sculpture. Prominently placed in the center of the top of the Renaissance-style carved cabinet are a Neoclassical-style head of a man, possibly Voltaire, in marble or plaster and an Egyptian-style figurine in terracotta (fig. 1c ↩). As with the two paintings, these sculptures contrast in subject, style, and scale as well as in materials. However, they appear more sympathetic to each other since the male head tilts toward the feminine-looking standing figure. Together, these works exemplify the increasingly anatomically accurate rendering of the figure, which by the nineteenth century assumes a human scale and expresses emotion through realistic gestures like the tilted head. Through these juxtapositions, Chase united geographically and temporally diverse objects, creating unexpected propinquities that resist clear allegorical or narrative expectations.

The collection in The Connoisseur—Studio Corner has less diversity in subject but greater variation in type than Studio Interior. This painting with its more intimate setting showcases the human form: from left to right, two paintings of full-length, standing women in contrasting up-to-date black and white dresses, most likely copies of Chase’s own work, hanging on the wall; a reproduction of a classical bronze statue of Narcissus on a pedestal in the corner; a roughly sketched figure, possibly a monk, in a landscape on a probably Chinese textile behind which hangs a ghost-like portrait head; an Asian face mask below which hangs a largely obscured, profile view of a Peruvian shrunken head, most likely a tsantsa, with a dark complexion, long hair, and equally long lip strings, originally intended for ritual purposes but sometimes carried by Chase in his pocket with the intent of shocking those he encountered.[68] The contrasting types of human forms—male and female—from different cultures and periods and with antithetical functions—decorative and ritual—are beautiful and ugly; ideal and disturbing; refined and brutal; classical and exotic. Such a wild assemblage of objects can only coexist in an eclectic collection, in which the art lies in balancing these oppositions with pictorial devices, such as selective detail and overlapping, to convince viewers of cohesion and “the mastering [aesthetic] vision.”

Another significant visual adjacency in the artful interiors is the propinquity of the young woman to the eclectic collection. As discussed earlier, she assumes the character of a connoisseur, looking at images in a large volume or a portfolio. While her humanity and her activity distinguish her from the inanimate stuff around her, the things in her immediate vicinity characterize her identity in a manner that recalls how objects and pictures-within-pictures in seventeenth-century Dutch paintings functioned to elaborate profession, taste, or an overarching symbolic sense of self.

In the center of Studio Interior, Chase surrounded the young woman with an eclectic array of fine and decorative art, setting up adjacencies with varying significances. The eye-catching shiny brass salver and the intense red textile beside her on the bench draw attention to her; their beauty arguably enhances hers. The reproduction after Hals’s Malle Babbe, diagonally above and to the left of the female figure, illuminates through opposition, rather than similarity, the figure’s characterization as an ideal “woman in white.” The Malle Babbe, cloaked in black and known for her threatening grimace and lewd behavior, accentuates by contrast the female figure’s gentility and purity, signified by her white dress, unblemished skin, and cultivation, evoked by her controlled posture and her activity of looking at art. These antithetical figures—old and young; ugly and beautiful; uncivilized and refined—create a striking opposition reinforced by their gazing in opposing directions. This juxtaposition might allude to a moralizing adage about fading beauty in old age, but given Chase’s departure from convention, it seems unlikely that he sought to convey such a predictable vanitas theme.[69]

In The Connoisseur—Studio Corner, Chase intensified the relationship between the female figure and the objects by adopting the “cozy corner” format, in contrast to the elongated, more panoramic composition of Studio Interior. Here, the woman, situated in the middle of the composition, becomes “the centre upon which relations are concentrated and from which they are once again reflected” in contrast to Studio Interior’s female figure who appears in front of a frieze-like arrangement of things.[70] The “cozy corner” composition produces a hub-and-spoke-like configuration, creating adjacencies, and by extension comparisons, between her and each of the objects in her surroundings. She acts as a unifying agent yet, as in Studio Interior, her associations with the things around her vary. For example, she resembles most closely the women in black and white portrayed in the paintings hanging on the wall, yet remains distinct from them in her seated rather than standing position and rose-colored attire; her pose recalls the self-absorbed character of Narcissus despite their contrasting genders and appearances (nude versus clothed; mythological versus real); her profile seems to echo that of the shrunken head, yet they differ in gender, facial features, and states of being, alive versus dead. Rather than highlighting one key pairing, Chase created a more complex composition, encouraging viewers to consider the charged adjacencies generated by the juxtaposition of the female figure and the collection. In doing so, the relationship of the woman and the objects reinforces the dynamic semi-lattice organization of the collection itself.

Along with creating a cozier space, Chase included more overt references to Aestheticism in The Connoisseur—Studio Corner. He clothed his female figure in an Aesthetic-style dress and represented her in the guise of an Aesthete closely eyeing images. Moreover, she is placed in front of a sculpture of Narcissus who has a similarly contemplative pose, suggesting her identification with the mythological figure that had come to signify the self-absorbed Aesthete during this period. However, as tempting as it might be to situate the artful interiors squarely in Aestheticism, it is important to remember that Chase, who advocated for the personalization of art, did not follow exactly Aestheticism’s prescriptions for the interior. Objects with deep personal resonance, like the shrunken head in The Connoisseur—Studio Corner or Malle Babbe in Studio Interior—do not conform to, even disrupt—“the pursuit of beauty,” which Aesthetes deemed essential to the construction of an environment for living.[71] Instead, Chase’s eclecticism includes objects that belong more in a cabinet of curiosity than in a late nineteenth-century Aesthetic-style interior with its single-minded emphasis on attractiveness and beauty.

Chase did not bring together objects from the past and the present, according to objective criteria. In the installation of his collection, he did not adopt existing judgments about or categories of objects, and he did not follow established hierarchies and chronologies. He did not label his objects like those in museums or department stores, nor did he reduce the collection of objects to a fixed, predictable, and easily identifiable system. Rather, Chase developed his own eclectic method of organization, informed by European precedents he had seen in artist’s studios while studying abroad. He treated fine art and applied art equally, arranging side-by-side paintings, sculptures, dishes, vases, fans, masks, shields, and musical instruments. In doing so, he defied long-held systems of value, and he neglected categorization by cultural and historical context to create meaning in unprecedented, if not provocative, adjacencies that expressed his desired cosmopolitanism as well as his own peculiar tastes.

Eclecticism and the Self

By the second half of the nineteenth-century, the décor of both the artist’s studio and the domestic interior had become a means of self-presentation. Within this context, eclectic collections became an earmark of individuality and were used to celebrate the heterogeneity of the self. In the decorating and collecting literature of the period, individuals were encouraged to develop tastes, to make informed choices, and never to copy slavishly the décor of others. A contributor to the Magazine of Art advised readers to “be selfish, be thoroughly selfish in the matter of decoration—be selfish in your choice of pictures.”[72] For that author, to be selfish meant to be sincere. Similarly, in his decorating manual, The House Beautiful, Clarence Cook (1828–1900) argued that the living room “ought to represent the culture of the family,—what is their taste, what feeling they have for art; it should represent themselves, and not other people.”[73] Eclectic arrangements in interiors, which by definition corral a variety of objects, but do not essentialize or standardize them, helped individuals to project themselves.

Artists’ studios with eclectic arrangements were seen as challenging convention. In her study of American consumption patterns during the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era, historian Kristin Hoganson elaborates:

Although artistic studios resembled museums and department stores in their eclectic display, they were not intended as symbols of scientific rationality or commercial values. Instead, contemporaries understood them as protests against conventionality, as expressions of a sometimes shocking open-mindedness, ease, sensuality . . . , and even decadence. Instead of exhibiting a strong desire for conformity to standards of respectability, such interiors showed a powerful desire to flaunt these standards.[74]

Chase and his contemporaries could attack convention with eclectic ensembles that transcend national boundaries. As Hoganson remarks, “There is a certain irony in expressing one’s individuality through exotic goods admittedly disassociated with the self,” but she goes on to explain that “the householders who strove for a cosmopolitan décor aimed to express a fluid individuality, notable for its receptivity to wider currents and outside influences.”[75] The artful interiors share this aim for “a fluid individuality,” tolerant of and open to diverse cultures and ideas. Chase even encouraged his students to adopt a cosmopolitan attitude toward art: “Be vital in a big, art way. Let ‘Art for Art’s sake’ be the key-note. Seek to be artistic in every way. Make exchanges. Keep an outlook on what the whole world is doing in art. The influence of provincialism is weakening. One becomes very small under [sic] narrow environment.”[76]

Along with thwarting convention by not being bound by geographical borders or nationality, artful interiors crafted a sense of self without temporal limitations. They visualize the late-nineteenth century notion, advanced by the British art and literary critic Walter Pater (1839–94) in 1868, that “the composite experience of all the ages is part of each one of us.”[77] Thinking about the self as connected to the past rather than simply of the present was relatively new in the United States, only taking hold following the Civil War.[78] When Chase presented his objects from the past to visualize a sense of self, he worked with a concept that only had a short history in American culture.

The cultural phenomenon of eclecticism afforded not only a means for capturing a desired cosmopolitan and cross-historical identity, but also a way to counter the serialization and standardization of mass production in the hope of guaranteeing both the originality and irreproducibility of “the mastering vision.” In his artful interiors, Chase did not repeat the same arrangements nor did he create a series of images with only subtle alterations from one to the next; each studio scene is unique. As a result, his atelier images seem to fend off “the homogenization of existence, the general evening-out of singularities, the desublimation of difference,” poignantly felt in response to the rise of mass production in the latter half of the nineteenth century.[79] Like many of his artist-friends, Chase vocalized his concern about the deleterious effects of industrialization on the art world and everyday life. He frequently denounced its labor-saving devices and its money-making agenda, and in a 1906 talk at the New York School of Art, he expressed hope that “people will oppose the production of machine-made goods.”[80] Furthermore, in this same talk, he attributed what he saw as a dearth of masters to “machine productions,” commenting that machines have “taken the place of the handiwork of the masters, and this method has not only checked and prevented the work of master painters, but made it almost impossible, and I know this to be true as evidenced by what we have to-day.”[81] The artful interiors are filled with the kinds of handmade objects he admired. Admittedly, he also included some reproductions (for example, Malle Babbe and the Narcissus sculpture), but their inclusion can be justified by his claim that such works were only suitable “in the hands of an artist.”[82] As already mentioned, the artful interiors contain pairings and groupings of objects that do not reappear elsewhere, and the treatment of the objects in each painting varies. This singularity and specificity counteracts the sameness and repetitiveness that were part and parcel of commercial goods. The individuality of the ensembles and the choice to paint with less or more detail guarantees the “fresh” and innovative look that Chase desired; as he expressed to his students: “Don’t copy your own work”; and “Don’t paint a former subject in an effort to improve it.”[83]

Problems with Eclecticism

Chase embraced eclecticism; however, it may be the very aspect of his work that led to his mixed reception in the press. In 1909, William Howe Downes (1854–1941) regarded Chase’s eclecticism as a positive attribute, describing it as “refined, orderly, [and] intelligent” and seeing it as a distinctly American artistic trait.[84] However, decades earlier, commentators had attacked Chase’s artful interiors for not being American enough. In an 1884 review of a pastel exhibition at the gallery of Mr. W. P. Moore, a writer for the Art Amateur remarked: “It might as well be a studio in Paris as in New York.”[85] In the 1880s, Chase’s adoption of eclecticism put into question both his nationality and his individuality, and perhaps in response to such criticism he began to include more American furnishings and architectural details along with the European contents in his images of his studio in Shinnecock, Long Island.

Despite the variations in his artful interiors, several critics found their subject matter repetitive. A writer for the Brooklyn Eagle reviewed Chase’s work in the Society of American Artists exhibition in 1883:

William M. Chase seems determined that the public shall not forget that he paints in an elaborately decorated studio, and he exhibits at the Society another “Studio Interior.” The public must be pretty much aware by this time that Chase works in a handsome studio, and now they would like to be let into the secret of what he accomplishes in his handsome apartments. Why does he not put forth pictures instead of studies of studios?[86]

A year later (1884), in the previously mentioned review of the pastel exhibition, the correspondent for the Art Amateur made similar comments: “Mr. Chase has shown us a corner of his studio again for the twentieth time. . . . And so little is individuality sought after, that the same model appears without attempt at disguise in at least six of the drawings—a well-known model, and by no means an ill-looking one, but the iteration adds still more to the professional expression of the exhibition.”[87] Responding negatively to the use of the same female figure, this reviewer did not consider the practicalities of hiring models or the significant tension generated by her constant presence in an ever-changing environment. Instead, the woman in Chase’s works became the hallmark of the “professional” character of the entire pastel show, meaning that the artists had technical talent but the artworks were too mundane and lacked poetic ideals and inspiration.

Along with the writer from the Art Amateur, other critics attacked Chase’s studio interiors for their art-for-art’s-sake approach and by extension for their meaninglessness. A commentator from the Nation expressed his displeasure with Studio Interior: “No. 23, ‘Studio Interior,’ by William M. Chase, is a piece of showy, rather than good, painting. The subject has no unity, being the scattered paraphernalia of a modern studio—mere roba; and Mr. Chase has failed to bring out the interest which might be found in even so bad a subject were its chiaroscuro faithfully studied.”[88] Chase’s representation of his studio filled with objects from his eclectic collection risked devolving into meaningless stuff. For these reviewers, the objects did not appear to express or signify anything, and the incongruous combinations of objects were not understood as interpretable, in part because they were not rooted in existing ideas or allegories—in a shared culture. Their arrangement according to “personal conviction” was too personal, and the conventional allegories and narratives of romance were missing. As noted by the critic from the Brooklyn Eagle, Chase showed us where he painted, but not what.

Such criticisms coincide with broader cultural attitudes about eclecticism. As the nineteenth century progressed, curators and critics argued against the seemingly intuitive, eclectic installations in art and history museums. The Smithsonian Institution’s curator, George Brown Goode (1851–96), famously attacked the “chance assemblage of curiosities,” calling for a systemization of artifactual collections so as to promote “instruction rather than . . . mere sensation.”[89] By the turn of the century, conflicted attitudes toward the aesthetics of eclecticism had emerged: its supporters praised its variety and specifically American qualities, while its dissenters argued for its meaninglessness and its superficiality.

Conclusion

Today, Chase’s eclecticism retains its problematic character less for artistic and more for political and social reasons. Late nineteenth-century eclecticism, as previously discussed, is associated with the concept of cosmopolitanism, which, in turn, connects to the imperialist politics of this period. Americans and Europeans had access through travel and trade to goods from around the world and the financial and political power to acquire them. Within this context, Chase fabricated through his eclectic collection the illusion that he was a world traveler, touring around accumulating things along the way. However, in actuality, he made regular visits to Europe but never went to China, Japan, the Middle East, or South America.[90] The limited nature of his trips abroad led the art historian Holly Edwards to classify him as “a studio Orientalist, one whose notions of the Orient imbued his diverse personal spaces with an entrepreneurial touch of the exotic.”[91] With this classification in mind, Chase also might be regarded as “a studio eclectic.” While this inauthenticity might not have disturbed his audience, it may seem unsettling now: the phenomenon of eclecticism itself, with its tendency to composite distinct cultures thereby linking them and potentially overriding their differences, may give us pause.

Setting aside but not overlooking these criticisms and acknowledging that we should not hold a nineteenth-century artist to present-day standards, we might regard Chase’s eclecticism as the foundation of one of his most significant contributions to the history of American art: the artful interior. The representation of this kind of interior began with Chase’s studio pictures in the early 1880s and concluded around 1920 when painters devoted little attention to this motif or stopped painting it altogether. Many of Chase’s artist friends, particularly those who, like him, were members of the Ten American Painters—Frank Weston Benson (1862–1951), Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938), Joseph Rodefer DeCamp (1858–1923), Frederick Childe Hassam (1859–1935), Robert Reid (1862–1929), Edward Charles Tarbell (1862–1938), and Julian Alden Weir (1852–1919)—had specialized in this subject, as exemplified by Hassam’s painting, Tanagra (The Builders, New York) (fig. 25). Rather than inventing something entirely new, Chase upheld the belief that innovation arose by combining the best elements from existing sources. His approach to art connects him with a transnational phenomenon and a nineteenth-century belief, promoted by Cousin among others, that progress in art and culture was not possible without eclecticism.[92]

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to Petra ten-Doesschate Chu and Robert Alvin Adler for their editorial expertise and Elizabeth Buhe and Allan McLeod for their assistance with the digital components, design, and layout of this article. I want to thank Marisa Bourgoin at the Archives of American Art, Kimberly Orcutt and Deborah Wythe at the Brooklyn Museum, and Alicia Longwell and Michael Pinto at the Parrish Art Museum for their assistance in obtaining images. Like Chase’s collection, the content of this article developed out of an eclectic process of “taking the best” from numerous discussions with colleagues, and I am especially in debt to Linda Docherty, Gregory Donovan, and Susan Sidlauskas for sharing their thoughts and for their encouragement.

[1] Frances Lauderbach, “Notes from Talks by William M. Chase: Summer Class, Carmel-by-the-Sea, California: Memoranda from a Student’s Note Book,” American Magazine of Art 8, no. 11 (September 1917): 434. Lauderbach was one of Chase’s students in California.

[2] “William M. Chase as a Teacher” in Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 11, no. 12 (December 1916): 252, doi:10.2307/3253798. This article consists of a series of extracts from the stenographic report of a talk given by Chase at The Metropolitan Museum of Art on January 15, 1916.

[3] Since the nineteenth century, the terms “eclectic” and “eclecticism,” albeit with differing connotations, have appeared in the literature on Chase and his work. For William Howe Downes, the eclectic character of Chase’s art identified him as a paradigmatic American artist: in 1909, he declared Chase was “a typical American artist,” explaining that his “susceptib[ility] to the best traditions of the art,” and his style generated through “a process of fusion,” characterized him as such. As Downes described, “American painting at large is undeniably pervaded by a refined, orderly, intelligent eclecticism, which has in it more cleverness than inspiration, more skill than passion.” He went on to clarify that “the national style, so far as there can be any American style, is a composite blending indistinguishably the influences of old and new schools of painting.” William Howe Downes, “William Merritt Chase, A Typical American Artist” International Studio, December 1909, xxix. Almost a century after Downes’s 1909 review, the curator H. Barbara Weinberg designated Chase a “consummate” and “an unabashed eclectic,” suggesting both his mastery and unapologetic embrace of this manner of artmaking and collecting. She argues: “Chase’s eclecticism merely amplified his generation’s wish to craft, with pride and pleasure, an American art from the best that the world had to offer.” H. Barbara Weinberg, “American Artists’ Taste for Spanish Painting” in Gary Tinterow and Geneviève Lacambre, Manet/Velázquez: The French Taste for Spanish Painting, exh. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press), 280. In a related interpretation, the art historian Barbara Gallati proposes that Chase developed “the ‘composite’ concept” to resolve a “fundamental conflict—how to be American and still function within an international culture.” She elaborates: “Chase devised this mechanism of synthesis, or the ‘composite’ concept, in response to negative criticism that converged on him as the most visible American proponent of the Munich style.” According to Gallati, the composite method served to mollify critics who argued that Chase, who had studied abroad in Munich, was too reliant on a European manner of painting. Barbara Dayer Gallati, William Merritt Chase: Modern American Landscapes, 1886–1890, exh. cat. (New York: Brooklyn Museum of Art in association with Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2000), 21.