The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Face to Face: The Neo-Impressionist Portrait, 1886–1904

Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis

June 15–September 7, 2014

Previously at:

ING Cultural Center, Brussels

February 19–May 18, 2014

Catalogue:

The Neo-Impressionist Portrait, 1886–1904.

Jane Block and Ellen Wardwell Lee with contributions by Marina Ferretti Bocquillon and Nicole Tamburini.

New Haven, CT and London: Indianapolis Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2014.

256 pp.; 105 color illus; 3 b&w illus; artist biographies; appendix on Neo-Impressionist oil portraits, 1886–1904; bibliography; index.

$65.

ISBN-13 978-0-300-19084-7

The term Neo-Impressionism invokes images of contrasting colors, gradations in light, and the signature pointillism of dappled brush strokes. As Ellen Wardwell Lee, the Wood-Pulliam Senior Curator at the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA), argues, the movement’s focus on “the creation and capture of brilliant color and natural light” has produced a Neo-Impressionist canon largely comprised of “landscapes, seascapes, and urban scenes” (IX). From Seurat to Signac, outdoor views have come to exemplify Neo-Impressionism’s aesthetic goals and practices, serving as the “primary vehicles for analyzing Neo-Impressionist technique” (IX). Lee concludes that “as a result, Neo-Impressionist portraits and their place in the modern era have received insufficient attention” (IX). The IMA’s exhibit Face to Face: The Neo-Impressionist Portrait, 1886–1904 seeks to counter this lapse, shifting public and academic focus to the portrait as a way to expand our notions of Neo-Impressionism. In her introductory remarks at the opening of the exhibit, co-curator Jane Block, Andrew Turyn Professor Emerita of Library Administration at the University of Illinois, stated that the goal of Face to Face was to “reassess” the Neo-Impressionist movement and, importantly, “incorporate portraiture into the canon of Neo-Impressionism.”

The IMA originated and organized the exhibit, which premiered at the ING Cultural Center in Brussels, and is host to its only showing in the United States. Face to Face highlights the IMA’s impressive collection of Neo-Impressionist works, notably from the W. J. Holliday Collection, and years of collaboration between co-curators Lee and Block, whose extensive research and publications on Neo-Impressionism culminate with Face to Face. The exhibit is housed in the IMA’s Allen Whitehill Clowes Special Exhibition Gallery, located fittingly adjacent to the Sally Reahard Suite of European Art, namely the galleries featuring Gauguin and the Pont-Aven School, 1886–1896; and European Modernism, 1900–1945. The two permanent galleries contextualize the Neo-Impressionist exhibit within concurrent artistic movements in Europe.

Face to Face opens with an enlarged detail from Georges Lemmen’s 1894 The Two Sisters or The Serruys Sisters (figs. 1, 2). The detail from The Two Sisters as the inaugural image announces the IMA’s founding role in the exhibit. Indeed, The Two Sisters, from the IMA’s permanent collection, both opens and closes Face to Face, the painting showcased in the final gallery. From the opening graphic, viewers move into the entry gallery of the exhibition, which serves as a textual and visual introduction to Neo-Impressionism. An explanatory text and wall plates outline Neo-Impressionism’s formative notions of color theory. The room features examples of period treatises on color, light, and optics, including works by Charles Henry (1859–1926), Michel-Eugène Chevreul (1786–1889), and Charles Blanc (1813–1882), each one a key influence on Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and the later Neo-Impressionist movement. The entry gallery also presents a video reproduction of Seurat’s Un Dimanche à la Grande Jatte (1884–86, Art Institute of Chicago), which anchors the exhibit that follows with Seurat and his celebrated painting as model and inspiration for the subsequent development of Neo-Impressionism. The final descriptive element of the entry gallery compares reproductions of Édouard Manet’s Nana (1877, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Berlin) and Seurat’s Young Woman Powdering Herself (1889–90, The Courtauld Gallery, London). Parallel details from each painting are enlarged and placed side by side with wall plates that guide viewers in a comparison of Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist style (fig. 3). From the women’s faces and arms to comparable table legs, the two portraits illustrate differences in brush stroke, posture, framing, and color.

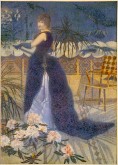

Viewers embark on their discovery of Neo-Impressionist portraiture in Paris, specifically in front of Madame Hector France by Henri-Edmond Cross (1891, Musée d’Orsay, Paris). The painting of the artist’s future wife colors the typical trappings of a society portrait: full-length woman in profile, posed in gown, gloves, and jewels in a formal or interior setting, with Neo-Impressionist style: pointillist brush strokes and contrasting hues (fig. 4). Such an introduction to Face to Face announces the major theme of the exhibit: the ways in which the Neo-Impressionists used the genre of portraiture as a means to further explore their aesthetic techniques. This theme directly correlates with the exhibit’s larger goal, which is to document the crucial role of portraiture in the articulation and evolution of Neo-Impressionism.

The first gallery of Face to Face consists of two rooms, both of which house portraits exclusively by French artists: Henri Delavallée (1862–1943), Albert Dubois-Pillet (1846–1890), Achille Laugé (1861–1944), Maximilien Luce (1858–1941), Hippolyte Petitjean (1854–1929), and Paul Signac (1863–1935). The gallery provides a rare viewing of Signac’s Opus 217: Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones and Tints, Portrait of M. Félix Fénéon in 1890 (1890–91, Museum of Modern Art, New York) (fig. 5). Opus 217 is both a portrait of Félix Fénéon (1861–1944), the French art critic and ardent supporter who coined the term Neo-Impressionism, and of the Neo-Impressionist movement: the group’s attention to period theories of optics, as well as the influence of “Japanese woodblock prints and the decorative line,” called forth in the kaleidoscope of colors and patterns of the background (33). The exhibit walls of the first gallery are painted in a deep blue, which showcases the colors of the featured portraits. Moreover, the blue walls of the first gallery contrast to those of the second gallery that are painted in a warm cream color, almost gold. The alternating blue and cream walls mark the different exhibit spaces in a playful enactment of the Neo-Impressionist use of contrasting warm and cold hues as a means to heighten the visual experience of color.

Moving from blue to cream, from the first to the second gallery, also means a border crossing in that the second gallery takes the viewer to Brussels and the work of the Les XX, the Belgian avant-garde artistic group whose regular exhibits (1884–1893), in conjunction with the Brussels weekly, L’Art Moderne (1881–1914), helped spread and shape Neo-Impressionism (10–20). The first room of the second gallery includes portraits by Georges Lemmen (1865–1916), Henry van de Velde (1863–1957) and Théo van Rysselberghe (1862–1926). The room also offers viewers a series of short videos that frame the works and Neo-Impressionism with information about the science, politics, technology, and social mores of the period. The second room of Gallery Two reunites three individual portraits of the Sèthe sisters by Van Rysselberghe (fig. 6). The portraits were commissioned by Gérard and Louise Sèthe, who “raised [their daughters] in an haute bourgeoise household of wide-ranging musical and artistic sensibilities” (51). The portraits highlight this upbringing as they portray Maria and Irma with their musical instruments, while Alice is posed in the rich interior of the Sèthe house complete with an Oriental figure on the mantle, a decorative sign that invokes the period vogue of Japanese art (171).

From oil portraits, Face to Face moves to drawings. The third gallery includes a selection of portraits in pen and ink, charcoal, conté crayon, and lithographs. Of note is Georges Lemmen’s portrait of the American dancer Loïe Fuller (1893–94, Collection of Greta van Broeckhoven) in conté crayon (fig. 7). The combination of gradations and shadowing in black and white with sinuous lines and hash marks makes for a simultaneous abstract and accurate portrait of Fuller and her signature serpentine dance. The gallery of drawings, the majority of which are in black and white, gives visitors a unique and often unseen view of Neo-Impressionism in which the group’s characteristic use of color is stripped away to reveal the power of its artists’ variance in style and application of strokes to produce light, shadow, and texture.

The final gallery, consisting of one large room, stands as both the apex of Neo-Impressionism and Face to Face. The gallery features ten portraits by Van Rysselberghe, Jan Toorop (1858–1928), and Lemmen. The paintings range from individual sitters to small groupings and from interior to exterior settings. What is striking about the ensemble is the ways in which the painters display their mastery of Neo-Impressionist technique: pointillism, color, and light, without overwhelming the personality or character figured. Consider Lemmen’s The Two Sisters or The Serruys Sisters (1894, Indianapolis Museum of Art) (fig. 8). Here, Lemmen has employed contrasting colors throughout the portrait, from the girls’ smocks to the blue background and the adjacent table, vase, and plant. The separate visual elements contrast in color and each element, in turn, is comprised of contrasting pointillist strokes, a process that extends to the painting’s original pointillist frame. As Block summarizes, “Lemmen’s last pointillist portrait is a tour-de-force of Neo-Impressionist principles put into practice” (118). Lemmen’s aesthetic prowess, however, does not eclipse his subject matter. Rather the artist’s use of color, positioning, clothing, posture, and gaze highlights the sisters’ tight familial bond and their marked individuality. Portraits by Van Rysselberghe and Toorop parallel Lemmen’s closing painting, demonstrating a collective command of Neo-Impressionist technique and the larger, historical genre of portraiture.

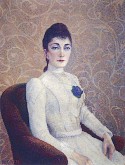

It is this combination of technique and genre that is Face to Face’s greatest strength. Through a careful and chronological display and contextualization of Neo-Impressionist portraits, the exhibit illustrates the evolution of the movement. Albert Dubois-Pillet’s Portrait of Mademoiselle B. or The Lady in the White Dress (1886–87, Musée d’Art Moderne de Saint-Étienne Métropole) in Gallery One introduces viewers to the Neo-Impressionists’ early use of portraiture, in which the pointillist technique takes shape within a limited palette (fig. 9). “Yet,” as Lee notes, “the careful dots that compose the model’s face do not explain her gravitas; they yield no clues to the thought or emotion behind the imperturbable countenance” (71). Painted more than ten years after Dubois-Pillet’s portrait, and presented at the close of Face to Face, Van Rysselberghe’s 1901 Three Children in Blue (The Three Guinotte Girls) (Private Collection) marks a shift in Neo-Impressionist technique and portraiture (fig. 10). Dubois-Pillet’s tight dots give way to Van Rysselberghe’s loose strokes, and the use of contrasting colors becomes more fluid. Of equal importance, as Face to Face demonstrates, is the development of the Neo-Impressionists’ approach to portraiture. Whereas Dubois-Pillet’s portrait presents a flat, impenetrable persona, the sitter yet to be identified, Van Rysselberghe’s painting captures both the universality of youth and the unique character of each of the sisters. In Block’s words, “Van Rysselberghe’s Neo-Impressionism was now in the service of a graceful yet relaxed articulation of form and character” (202).

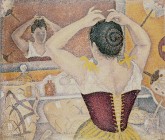

While much of Face to Face focuses on Neo-Impressionist technique, from the wall plates and explanatory text to the photo booth in the reading room that allows visitors to create a digital, pointillist self-portrait, additional themes emerge from the exhibition, namely the domestic sphere and woman as model. From gallery to gallery, Face to Face features numerous portraits of women: mistresses, wives, sisters, daughters, and mothers. In room two of Gallery One, for example, five of the seven portraits exclusively depict female family members. In Gallery Four, eight of the ten portraits are of women. The predominance of female figures reminds viewers of woman’s historic role as canvas. As Face to Face makes evident, Neo-Impressionism is no exception. The female body, clothing, hair, and traditional domestic setting serve as studies in line, color, light, and texture. Many of the portraits in Face to Face portray women with downcast eyes; they are either looking away or engaged in an activity, such as sewing, reading, or dressing. Signac’s Woman Arranging Her Hair, Opus 227 (Arabesques for a Dressing Room) (1892, Private Collection) epitomizes such use of the female form (fig. 11). The painter’s mistress and future wife appears in her dressing room, the ribbons and lacing of her corset set against her pale skin, colored bodice, and dark hair. The curves of her arms, fingers, and waist parallel the design on the basin and pitcher, as well as the glass bottles and decorative fans. Every detail is accounted for, except the woman’s face, which is blurred. Typical of Signac’s repeat rendering of Berthe Roblès (1862–1942), the obscured face nonetheless symbolizes art’s recurring treatment of women, the female body as form or, in Signac’s case, a series of arabesques (150). One could argue that Signac’s Woman Arranging Her Hair, Opus 227 is not a portrait, but rather—as suggested—a study in form. Similarly, the exhibit’s numerous paintings of women engaged in domestic activities fall under the historic category of genre painting. In fact, co-curators Lee and Block employ the term portrait very loosely in their conception and execution of Face to Face. While many of the paintings in the exhibition fall outside the strict definition of a portrait, Lee and Block’s broad interpretation of portraiture works to their advantage. It allows them to assemble a wider variety of paintings: traditional portraits, genre paintings, and studies in the human body and its accoutrements. And, as Face to Face makes clear, the different approaches overlap; each one contributes to the Neo-Impressionists’ larger collective effort to visually represent and analyze the individual and form.

Missing from Face to Face, however, is the work of Anna Boch (1848–1936), the only female member of Les XX. Boch figures metonymically in Face to Face via two portraits by Van Rysselberghe, including Van Rysselberghe’s 1892 Portrait of Anna Boch (Michele and Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Massachusetts), in which Boch is depicted working in her studio (fig. 12). The absence of Boch’s own paintings in the exhibition is regrettable. The omission may be due to the relative unavailability of Boch’s portraits, which are few in comparison to the large number of landscapes that dominate her œuvre. Moreover, Boch’s absence from the exhibition does not alter the overwhelming success of Face to Face.

The exhibition of 49 works is small enough to be studied in detail and yet includes enough depth and variety as to document Neo-Impressionism and its experiments in portraiture. The open exhibit and gallery spaces facilitate mobility from room to room and back again, as well as visual comparisons of works across galleries. Albert Dubois-Pillet’s Portrait of Mademoiselle B., for example, which hangs in room one of Gallery One, can be seen from both room two of Gallery One and room one of Gallery Two, a view that encourages visitors to compare Dubois-Pillet’s opening Neo-Impressionist portrait with the aesthetic progression that follows (fig. 13). The exhibit also introduces American audiences to a number of works housed in Europe. Likewise, visitors explore the breadth of Neo-Impressionism beyond the group’s father, Seurat. The accompanying exhibition catalogue, cited throughout this review, is equally dense, offering readers an introduction to Neo-Impressionist portraiture and detailed analysis of specific paintings, artists, and techniques. Finally, Face to Face, like the paintings it presents, can be read on multiple levels. From Neo-Impressionism to portraiture to form and technique to family and gender roles, the exhibition asks viewers to appreciate and interrogate the paintings before them. Visitors come face to face with Neo-Impressionism and the many individuals and ideas that shaped its aesthetic evolution. In this viewing of portraiture, we see versions of our own face reflected, the Neo-Impressionist portraits ultimately marking both an artistic movement and their subjects’ humanity.

Keri Yousif

Associate Professor of French

Department of Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics

Indiana State University, Terre Haute

Keri.Yousif[at]indstate.edu

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank Stephanie Perry, Public Relations Manager at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, for her generous and timely assistance with a preview of the exhibit and the photographs for this review.