The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Il était une fois l’Orient Express

Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris

April 4–August 31, 2014

The monumental exhibit Il était une fois l’Orient Express transports visitors into the world of elegance, mystery, and anticipation that characterized travel from Europe to the East from the later 1800s through the 1970s. On display from April 4–August 31, 2014, this exhibition was the product of a partnership between the Institut du Monde Arabe and the French National Rail Company (SNCF), and showcases the gems of each organization. Visitors to the Institut du Monde Arabe are greeted by the Orient Express, the fully furnished, four-car train parked outside (fig. 1). Paired with two additional rooms inside the museum, chief curator Claude Mollard’s display highlights the lavish culture of train travel and the fantasies that it inspired.

From its maiden voyage, which departed the Gare de l’Est on October 4, 1883 bound for Istanbul, the Orient Express became the most fashionable mode of travel for anyone with the financial means to do so. Filled with a company of writers, journalists, and sovereigns, this moving luxury hotel provided both comfort and a place for the passengers’ imaginations to flourish during this three-day, two-night trip. The Istanbul stop functioned as a gateway for European travelers, who then could take the Taurus Express to terminuses such as Baghdad, Cairo, and Tehran. Although likely a voyager’s first experience visiting Africa or the Near East, a half-century of Orientalist painting, writing, and fascination primed the expectations of those on the train. Il était une fois l’Orient Express, the first time the Orient Express was on public display, showed the dreams and myths of both the East and train travel through a diverse assortment of media. Uniting films, magazines, posters, paintings, and photography, the exhibit transforms the train cars into a museum and devotes considerable gallery space to all things historical so that visitors could grasp the importance of this particular train, and of railroad travel in general. Visitors began their experience of the nineteenth-century train trip by purchasing their tickets to the exhibition outside at a makeshift station (fig. 2). The five-piece train installed on the pavement of the Institut du Monde Arabe included a locomotive, wagon-restaurant, and three train cars, with these latter three open to exploration by visitors.

The first carriage that the viewer enters is the Flèche d’Or, which was constructed in 1929 and restored in 1987 (fig. 3). The viewer-passenger navigates the narrow aisle bordered by small tables and plush, overstuffed chairs. Even with the car at a standstill, the visitor’s eye moves briskly around the space, trying to absorb every detail of this intricate, warm interior. To best demonstrate how the car would have appeared in situ, each of the ten tables is covered with objects, from brandy bottles and newspapers to books and cigarettes. René Lalique’s sumptuous decorations heighten the prestige of the interior of the carriage with molded glass images of water nymphs between panels of Cuban mahogany (fig. 4). The Flèche d’Or sets the tone for the next two cars, and it immediately becomes clear why only the wealthiest and most prestigious Europeans had access to this mode of transport.

With such scénographie, it seems that the passengers had just left the train and would return to their seats within a few hours. To match the Orient Express’ famous passengers with a seat, luggage tags with a photo and a brief biography are attached to certain chairs, along with items emblematic of their person. Iconic performer Josephine Baker’s place, for example, is signaled by a dark fur muff and a small beaded purse. This set-up provides further perspective into the prestige of the era’s passengers and adds an element of didacticism to the already spectacular train car.

The visitor then entered the sleeping car, or voiture-lit. It was Georges Nagelmackers who first conceived of this type of train carriage in Europe: this allowed passengers uninterrupted overnight travel across long distances similar to the sleeping cars first created by George Pullman in Chicago in 1865. The car was designed with maximum space efficiency in mind; it is equipped with eleven compartments, eight with two beds and three with three beds. Although this carriage is clad in wood panels like the Flèche d’Or, the furniture and linens are plain, and the sinks and armoires of each individual cabin are equally modest. With one bed suspended from the ceiling and no other seating, the layout of the compartment highlights the necessity for the luxury and social space in the other cars, qualities that also had been visible in certain trains in the United States.

Clothes strewn on the bottom bunks and open suitcases, which display delicate unmentionables, add a personal touch to these carriages. In the final compartment, the exhibit fully engaged with the fiction that it inspired: a lifeless passenger lies on the bed, covered with a white sheet as blood pools on the blanket and floor. A reference to Agatha Christie’s 1934 novel Murder on the Orient Express, this scene clearly indicates how easily fantasy could mix with reality onboard the train.

The final car is the 1929 Train Bleu, a salon-bar also designed by Lalique (fig. 5). Its dark brown tones provide a marked contrast to the interior of Flèche d’Or, making it well suited for evening gatherings. Just in front of the fully stocked bar located on the passenger’s right, an upright piano offered an opportunity to serenade drinkers lounging on leather ottomans as well as diners. To brighten the dusky interior, Lalique employed white and silver floral motifs with inlaid medallions of flowers on each of the wall panels. Alcohol and cigarettes cover the small tables, and all that was absent was the light of the nighttime sky reflecting off Lalique’s glass orbs (fig. 6).

Although the train was the means by which Europeans arrived in ‘the Orient,’ the space itself did not perpetuate any of the passengers’ stereotypes or preconceptions about these foreign lands. Instead, it was a portable European home, a safe space that, despite the numerous attacks that pepper the Orient Express’ history, would be a familiar sight in the exotic East. The portion of the exhibit inside the Institut du Monde Arabe, therefore, was tasked with showing the voyagers’ expectations and anxieties regarding their cross-continental travels. It did so with a wide range of materials gathered from private and public collections; all the objects included in the exhibition reinforced the atmosphere of documented reality, reinforcing how things actually appeared in the train’s interior environment.

The first room inside the lower galleries of the museum was markedly darker than the train display outside. Here, the objects in their vitrines and the projected videos illuminated the dark blue walls of this windowless gallery space. From the first sweeping glance, the viewer saw the multiplicity of media on display; yet there was no obvious order in which to study them. According to Mollard, the intention was that the visitor could circulate freely among the displays via a variety of paths, just as the Orient Express had multiple routes and destinations. To the left was situated André Derain’s Charing Cross Bridge, London (1906, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) a colorful tableau of a train zooming across the distant bridge in the background. Immediately facing the visitor, the Frères Lumière’s 1895 film A Train Arriving at La Ciotat played on a table above which was an enlarged photograph of Nagelmackers, the person responsible for making the Orient Express a reality in Europe (fig. 7). On the left-most wall, three large projectors showed the Orient Express as it was portrayed in a selection of popular twentieth-century films (fig. 8). Overall, this first gallery highlighted the theme of the extent to which trains and the culture of travel and technology had saturated all aspects of French artistic imagination of the era, continuing well into the twentieth century.

To maintain the theme of rail travel as the visitor moved from the outside portion of the exhibit, the rooms and furniture in the first gallery echoed the train aesthetic. The vitrines were shaped like trunks, with the same leather detailing and secret compartments, which now function as pull-out displays for posters (figs. 9 and 10). In effect, the large-format videos resembled the windows of a train at night, as the viewer’s eyes constantly moved between them, scanning the maps, landscape images, and films that were being projected.

In the first large suitcase-vitrine, just across from the wall of video projections, the visitor found the reassuring comforts of the Orient Express (fig. 11). Isolated for closer examination, this display window housed Art Deco china that was used onboard, a conductor’s uniform, and a single, first-class compartment extracted intact from the train car (fig. 12). Even when traveling in those locales most distant from their European homes, the passenger on the Orient Express found familiarity in both the aesthetic created and in the practical use of these items. This setting indicated that no detail was spared when crafting these interiors, from the glass detailing around the washtub to the marquetry designs on the doors and cabinets, which, together, elevate the functional cabin to a work of art (figs. 13, 14). With such finery, it is not difficult to understand the many sabotages and robberies that dot the train’s history. One such incident was described on a nearby wall label: in 1891, eight years after the maiden voyage of the Orient Express, the train was attacked 60 kilometers from Istanbul by Greek bandits who wanted to secure many of the objects in the train or even to obtain hostages.

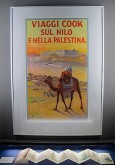

The first room of the exhibit also highlighted various other booming industries that contributed to the tremendous success of the Orient Express. A display of different sizes and types of trunks reflected how luggage design companies such as Moynat and Louis Vuitton, each founded in the in the mid-nineteenth century, provided travelers with sturdy and spacious means of keeping sartorial and personal effects organized (fig. 15). Additionally, the invention of lithography and its proliferation in fin-de-siècle France provided key advertising and colorful imagery to seduce the rich clientele. One such poster is the initial advertisement for the Orient Express from 1889, which shows a bird’s eye view of Istanbul and the train routes and times in the foreground. However, this placard is starkly monotone in comparison to later advertisements, such as Roger Broders’ Poster for the Simplon-Orient-Express, displayed in another drawer. Broders’ poster follows the same format as the first, but employs the well-established stereotype of a picturesque Istanbul illuminated by the sunset and a shimmering blue sea. The motifs used in these posters reinforced the best qualities that a visitor would find when traveling to these sites.

Reflective of the train travelers’ experiences after disembarking at their destinations, the final room of the exhibit demonstrates the European presence and interpretation of the Eastern locales of the Orient Express and its successor, the Taurus Express (fig. 16). The first wall label acted as an introduction to this gallery space, detailing the railway’s expansion in the 1880s as a European advancement onto Ottoman soil. This preface set the tone for the room, as a majority of the displayed objects were created or used by European voyagers, artists, and writers in the East.

In an attempt to show the European perspective on Eastern travels, this section did not shy from traditional orientalist themes such as the picturesque, the seductive odalisque, and the timeless archeology that so fascinated westerners (fig. 17). One of the first vitrines contained several early guidebooks written by famous authors such as Théophile Gautier and Pierre Loti (fig. 18). Loti is reprised later in the exhibit on a different wall through a portrait of the author in ‘Oriental’ costume and in a photograph of Loti dressed as the Egyptian god Osiris (figs. 19, 20). The fact that these two types of media—a guidebook intended to be factual and images that show the fetishization of the Orient—are created by the same author demonstrates the many vehicles for European consumption of the East (fig. 21). The wall labels, however, did not explicitly discuss this point, which was a weakness that was noted. Moreover, curator Gilles Gauthier was keenly aware of the colonial nostalgia that some visitors may have adopted with regard to the exhibit, but, on the whole, the concern for not perpetuating this mentality does not seem to be a priority. Only a single wall label explains the concept of the picturesque and its prevalence in European depictions of the East, but this explanation was not put into dialogue with any of the stereotyped scenes that are displayed.

However, by utilizing these orientalist tropes, the viewer discovered one of the hidden gems of the exhibit: on the backmost wall, we find Jean-Auguste-Dominque Ingres’ La Petite Baigneuse: Intérieur de harem (1828, Louvre, Paris). This 1828 work is displayed amidst a cavalcade of harem scenes and odalisques, such as Émile Bernard’s later Fumeuse de haschich [The Hashish Smoker] (1900, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and Paul Delvaux’s L’Âge de fer [The Age of Iron] (1951, Mu.Zee, Ostend) which is the exhibition’s most contemporary painting (figs. 22, 23). Ending the exhibit with L’Âge de fer—a notably Western odalisque who seems to be an allegory for the train in front of which she sits—suggests a blurring of the lines between East and West.

Although the most sensational portion of Il était une fois l’Orient Express was the train and items in situ, the extensive pedagogy of the display relied heavily upon the two traditional exhibition spaces found within the Institut du Monde Arabe. It is unfortunate that the long line of visitors both within and outside of the cars, all eager to take this unique journey back to an era of luxurious train travel, did not permit exhibit-goers the time to read the material or thoroughly study the personalities being portrayed. Due to the immense popularity and success of the exhibit, these concerns would only enhance the viewer experience for future expositions of this kind.

On the whole, Il était une fois l’Orient Express is more than a historical or art exhibition. Blending both art and history, this exhibit allowed visitors of all ages to better comprehend the fantasy—and the reality—of a bygone era of luxury travel to exotic lands. It posits that the traditional trip taken by voyagers to the classical world was experiencing a radical modification. After first being immersed in the full decoration and splendor of the train itself, the viewer’s understanding of this mode of lavish transportation, as well as the culture that developed around it, was enriched via the didactic rooms inside the museum. Moreover, by mixing the real train with the fiction that it inspired, the exhibit highlighted the extent to which, for the imaginations of an era, travel still maintained a luster and a sense of excitement. The real contribution of this exhibition, however, lies elsewhere.

In focusing on the proliferation of rail travel in the nineteenth century, the organizers of this exhibition provided a completely novel way to see how art was used and consumed. The carefully reconstructed interiors, and the ways in which hotels and publicity were employed, clearly demonstrated that art played a significant role in fostering new dreams. In this way, the exhibition was a model of its kind as it went beyond a historical reconstruction to show how art can be employed in practical contexts to achieve new ends.

Kylynn Jasinski

Ph.D. Student

University of Pittsburgh

KRJ14[at]pitt.edu