The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

A World Apart: Anna Ancher and the Skagen Art Colony

National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC

February 15–May 12, 2013

A World Apart: Anna Ancher and the Skagen Art Colony.

Elizabeth Lynch, editor, with contributions from Lisette Vind Ebbesen, Mette Bøgh Jensen and Elisabeth Fabritius.

Washington, DC: National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2013. Distributed by D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers, Inc.

144 pp.; 74 color and 10 b&w illustrations; artist biographies; exhibition checklist.

$24.95 [Published in English.]

ISBN 978-0-940979-50-5

The National Museum of Women in the Arts opened a significant door in introducing the Danish artist Anna Ancher (1859–1935) to American audiences. The beautiful rooms of the exhibition, careful lighting and uncluttered arrangement welcome visitors to enjoy her vivid palette and lively brushwork. Large photographs of the artist in her smock or in her home help generate a feeling of intimacy with this unfamiliar and very private artist (fig. 1). With the support of the Danish monarchy, embassy and the Oak Foundation and in partnership with the major repositories of Ancher’s work in Denmark, Skagens Museum and Anna and Michael Ancher Hus, the National Museum of Women in the Arts has assembled an extraordinary number of her canvases, as well as representative works of other members of the Skagen Art Colony from the end of the nineteenth century. All elements of the exhibit combine not only to make familiar, but also to bring acclaim to this artist who enjoys renown in Scandinavia and northern Europe, but is virtually unknown here in the United States.

Anna Ancher (née Brøndum) became part of an international art colony that formed in the 1870s in the town of Skagen located on the northern tip of Denmark’s Jutland Peninsula. She married one of the founding artists, Michael Ancher (1849–1927). Unlike other colonists, Ancher was a native of the town, and the Brøndum family owned the hotel that served as the central meeting spot for the artists’ gatherings. The Skagen Art Colony is linked to the Modern Breakthrough movement in Danish art in the 1880s, which eschewed the outdated and sentimental subjects propagated by the Academy for grittier subjects in painting, theater, and literature. The Modern Breakthrough was closely aligned with French realism and naturalism. Wall text at the introduction to the exhibition raises the visitor’s awareness of the gendered context of Ancher’s art. As a young woman in the 1870s, she had limited formal opportunities to train as an artist. One reads, furthermore, that in the early decades of the twentieth century she was “increasingly conscious that opportunities for women artists were limited”, leading her to join in the founding of Denmark’s Association for Women Artists in 1916. This group met initially in the studio of Ancher’s friend sculptor Anne-Marie Carl-Nielsen (1863–1945) to discuss art and practice, evolving to a more activist role in promoting education and exhibition for women artists.[1]

Thematically arranged rooms in the exhibition bade the visitor to meet Ancher’s family, to encounter the people of Skagen in their interior spaces, to gaze at images of the land and sea and to confront the breakthroughs she made in her art. Most rooms juxtapose Ancher’s works with exemplars by other Skagen artists. The neutral shades chosen by the curators and exhibition designers bring out Ancher’s vivid colors. Changes in wall treatments also mark changes in theme, guiding movement and attention through the different rooms (fig. 2).

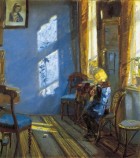

In each new section, clear titles and informed introductions articulate the organizing concepts. In the room “Interiors,” for instance, one reads about the distinctiveness of Ancher’s interiors in comparison to other Skagen painters. Her relationship to Paris as the modernist center is also indicated. We read, “In her attempt to capture the transient effects of light, Ancher shared an affinity with the Impressionists. However, unlike those artists, Ancher was more concerned with the physical shape that light takes and she painted it as a nearly tactile object, often using thick, impasto brushwork.” Sunlight in the Blue Room (1891, Skagens Museum), which earned international acclaim in the Paris International Exposition of 1900, demonstrates not only tactility as indicated in the text, but also greater abstraction, especially when viewed here close to Children Painting with Spring Flowers (1894, Skagens Museum) by Viggo Johansen (1851–1935) (figs. 3 and 4). Johansen’s energetic brushstrokes converged on his children gathered around a table; the viewer can easily read the painting and distinguish the relative degree of concentration his own children have in their task. In contrast, while Ancher’s canvas presents her daughter Helga, paint and color render her emotional and physical activity subservient to the brilliant squares of sunlight that transform the wall.

“Land and Sea” also contextualizes Ancher through proximity to works created by other members of the Skagen art colony, which helped shape the public visual memory and image of Skagen. Enormous canvases by Michael Ancher and Peder Severin Krøyer (1851–1909) dominate the room and exalt in the fishermen of Skagen in the 1880s, and by the 1890s, in its beaches (fig 5). As the curatorial text helps the reader understand, Danish popular imagination saw Skagen’s fishermen as modern heroes who helped to rescue boats caught in the perilous currents at Skagen’s tip, where the straits of Denmark meet the North Sea. The tan hues of the museum walls reinforce the realism in the boards of the fishermen’s boats. By 1890 the railroad arrived, bringing with it fashionable tourists who sought to bathe in the waters and to stroll on Skagen’s beaches. Naked boys enjoy the sparkling beach where the crystal splash of the surf meets the shore in Krøyer’s luminous “Wait for Us!” (1892, Skagens Museum), while fashionably dressed women stroll at twilight in Michael Ancher’s A Stroll on the Beach (1896, Skagens Museum) (fig. 6).

While perhaps surprising to the majority of museum-goers, Anna Ancher’s canvases constitute only a third of the canvases in this room, and as Assistant Curator Virginia Treanor lamented, are dwarfed by the grand scale of surrounding works. In order to compensate for the size differential, Treanor organized the walls in a rhythm that alternates between large and small canvases. The size incongruity, however, also raises a crucial point about differences in Ancher’s subjects. She painted neither beaches nor fishermen. In her canvases, Skagen emerges not only as “A World Apart,” a destination remote from the United States, but also at an apparent distance from the painted representations by other colonists. In contrast to Michael Ancher’s Fishermen Launching a Rowboat (1881), typical of most of his production from 1879 through 1900, Anna’s major figurative grouping, A Field Sermon (1903, Skagens Museum) shows intimate knowledge of both local topography and of the pietist religious revival in Skagen (fig. 7). Although naturalist painters in Germany, France and Denmark addressed the subject of rural devotion in contemporary works, Ancher’s take is quite different.[2] Skageners, mostly in local dress, gather around a preacher, outside on an identifiable grassy knoll, which is near the Skagen lighthouse. Despite such specificity, the figures seem to float in a disarmingly skewed spatial arrangement. Ancher disrupts the viewer’s orientation and blocks any possibility of ingress. The center of the canvas, the natural focal point, is empty; even its coloring is muddy and nondescript. Ancher forces the viewer to take multiple perspectives in order to make sense of the painting, simultaneously placing the viewer above the men, while looking up the hill at the women, and straight ahead at the preacher. Ostensibly a religious scene, the only sense of anything otherworldly is created by the lack of rootedness of the figures.

In another example of subject difference from Krøyer and Michael Ancher, Anna choses to paint agricultural subjects, such as Harvesters (1905, Skagens Museum) despite the economic importance of beaches and tourism to Skagen and its famous artists (fig. 8). In Anna’s painting, farm laborers march in a frieze-like procession along its upper register. This parade crowns a luminous field of golden rye that occupies the lower half of the canvas. The juxtaposition of Anna’s harvest scenes to the images of fishermen and tourists in one modest room (although the largest in the exhibit) begs the question of why Anna chose such different subjects. Her orientation away from the fabled shoreline to the rye field directs attention instead to other Danish contemporaries from outside of Skagen such as the painting Danish Landscape (1891, Statens Museum for Kunst) by Harald Slott-Møller (1864–1937) and the short story “The Waving Rye” (1911) by Jutland author Johannes V. Jensen (1837–1911).

"Land and Sea" thus establishes contrasts between Ancher’s work and her Skagen colleagues. The largest canvases in the room, by Michael Ancher and Krøyer, represent the picturesque shore through Skagen’s fishermen and beaches, whereas Anna’s A Field Sermon has moved inland and remains illegible. Her other canvases in the room are modestly scaled and show not only agriculture, but also empty streets and house facades. Although this arrangement of the room implies both an idiosyncratic choice of subject and hints at the lack of anecdote in Anna’s work, the contrast is not sufficiently highlighted in the narrative text. It is also disappointing that the wall label for “Land and Sea” suggests her lack of formal training rather than deliberate intention as an underlying cause for the paucity of large-scale canvases. This reductive explanation neglects to consider an expanded artistic context that includes Paul Gauguin’s Vision After the Sermon (1888) and Albert Edelfelt’s Women Outside the Church at Ruokolahti, (1887). As Washington, DC, audiences had the opportunity to view Gauguin’s painting in the spring of 2011, such a comparison could have underscored the modernist orientation of Ancher’s work.[3] Furthermore, the description distorts her artistic education and ignores evidence of intentionality. Vilhelm Kyhn (1819–1903) trained Ancher along with other young women in both landscape and figure painting, albeit at a smaller scale.[4] In addition, at the Michael and Anna Ancher Hus, one can see her careful preparatory studies, which are evidence of deliberate compositional choices, figure treatment and groupings she made in creating the Field Sermon, and actually suggest strong understanding of the necessary elements to make a large-scale canvas. Furthermore, by 1903 Ancher had been successfully exhibiting for over two decades. More in line with the central organizing concept of A World Apart would be to consider such works in relationship to her “breakthroughs” highlighted in the nearby room.

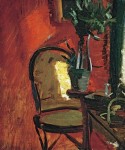

The “Breakthroughs” room provokes consideration of the essential question raised by Peter Nørgaard Larsen in the catalogue to Skagens Museum’s 2009 exhibition “I am Anna”. Larsen complained, “Why can’t Anna be modern?”[5] The aesthetic choice to display Ancher’s works solo, without the limiting reference to works by other Skagen colonists, in a room with clear lighting and the free façade of the white walls, intentionally emphasizes their modernism (fig. 9). The informative wall text directs the viewer to look for compositions constructed through light and color. Upon entering, the viewer faces a wall of canvases where her manipulation of pigment renders light with an unparalleled physicality in interiors that are sometimes abstracted, but always ambiguous. Both studies, such as Light on the Wall in the Blue Room (ca. 1890, Skagens Museum), as well as finished works, Interior (ca. 1916–17, Skagens Museum) and Evening Sun in the Artist’s Studio (after 1912, Skagens Museum), employ an avant-garde handling of light and space, described here as the “geometric quality of light reflected on walls” (fig. 10). The wall text directs us outside the colony and references Gauguin with whom her artistic circle was well acquainted. The label for the small work in the same room, Interior with Chair and Plant (ca. 1885–90, Skagens Museum) reiterates a possible visual connection (fig. 11). Importantly the viewer is also told to look for “barely recognizable subjects” as in Woman Knitting (ca. 1915, Skagens Museum), where the subject’s face, contour and volume are subjugated to the forms taken by light on the wall.

The captions in the “Breakthroughs” room carefully distinguish between studies and finished works. This is not always true in the other rooms. For instance, labels for The Maid in the Kitchen (ca. 1883–86, Skagens Museum) and A Funeral (ca. 1888–91, Skagens Museum) do not reference her larger, finished and exhibited works, which hang respectively in the Hirschsprung Collection and the Statens Museum for Kunst. This minor oversight misrepresents some of her more important early works.

The conceits of “A World Apart” continue many of the themes explored in the Skagens Museum’s 2009 show, I am Anna, curated by Mette Bøgh Jensen, and share the overall premise that Anna Ancher was ahead of her time. The Washington show includes many more examples from the most prominent male artists in the Skagen Art Colony within the galleries. Skagens Museum also framed Anna within the colony’s production. However, the museum specializes in the art of this group and could add this dimension by directing circulation through its main collection to view paintings of heroic fishermen and local Skageners, while excluding such works from the dedicated galleries of a show about Anna Ancher. The Skagens Museum enjoyed, therefore, greater freedom to explore Anna’s innovations in the handling of light and space and to consider her modernism through its creative pairings with artists outside the colony, ranging from Vilhelm Hammershøi (1864–1916) to David Hockney (b. 1937).

However, the Washington show is necessarily less adventurous, because art audiences in the United States have such extremely limited knowledge of either the Skagen Colony or Anna Ancher. While in Denmark, and especially in Skagen, there was no need to introduce this artist, in the United States there is only one known canvas in public collections, at the Oglethorpe University Museum in Atlanta, and Ancher has not been exhibited at so prominent a venue since the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Collections and exhibitions in the United States that feature the Skagen art colony or its artists are patchy at best. The museum faced the task of offering a primer on the artists and location, before it could elucidate the salient aspects of Ancher’s art. While most rooms include works by a variety of Skagen artists, the curators successfully accentuate Ancher’s individual tendencies by pulling exemplary works out from the main body of the exhibition into the separate “Breakthroughs” room.

Given the importance of Skagens Museum in both lending the core body of the exhibited works and in laying the groundwork for the show, it is not surprising that curator Jensen contributes one of the two essays in the catalogue and offered the first scheduled public gallery talk (fig. 12). The American audience was suitably impressed as the Danish Jensen gave an engaging overview of the galleries in clear and expressive English. She emphasized Ancher’s network of relationships with the members of the artist circle there. She asserted the importance of the support of Ancher’s husband and mother in enabling her to pursue an artistic career. Many of the works Jensen highlighted helped to develop a sense of Ancher’s role within the Skagen Art Colony. She situated Christmas Day (1900, Skagens Museum), Michael Ancher’s group portrait of Anna, her mother, sisters and daughter within the specific location of the Brøndum Hotel dining room (fig. 13). The dining room functioned as a social space for Skagen Art Colony gatherings and signified the key role played by Anna’s family as innkeepers, facilitating the town’s development as an art center.[6] Jensen contrasted Michael’s support of his wife’s artistic career to the ostensible lack of support offered by Krøyer for his wife, Marie (née Triepcke, 1867–1940), also an artist (fig. 12). As evidence, the Danish curator contrasted the directness and energy in Michael’s portrait of Anna Ancher Returning from the Field (1902, Skagens Museum) to Krøyer’s aestheticizing in depicting Marie on the beach in Summer Evening in Skagen (1892, Ny Carlsberg Glypotek), a point she reiterated in the catalogue essay (29–30). Jensen’s talk was most helpful in encouraging the viewer to recognize the extent to which the artist eliminated objects in her interiors that one would expect to see there. This emphasis directed the audience’s focus to her revolutionary handling of light and space.

Jensen was, in fact, assigned the project of introducing the Skagen painters in the catalogue as well. In addition to the introduction, written by Skagens Museum director Lisette Vind Ebbesen, there are only two essays, lamentably printed on green paper, in this otherwise very attractive book, including Jensen’s “The Skagen Painters: Plein Air Painting and Community.” Elisabeth Fabritius wrote the other, “An Unusual Fate: The Painter Anna Ancher.” The two essays in the catalogue encapsulate mainstream scholarship on Anna and the Skagen painters, again serving to introduce the artist rather than to reorient perspectives. The authors develop their topics chronologically, helping to balance the thematic arrangement of the exhibit with a narrative better known in Europe.

Fabritius focuses on Ancher’s extraordinary success in comparison to other female painters of her generation. She describes Michael’s early and radical advocacy on behalf of his wife, the support of her family, the importance of her travels to Paris in her development as a painter, and briefly, the ways in which Ancher’s work transcends the boundaries of the sphere circumscribing female artists.

In the second essay, on Skagen painters, Jensen discusses the conditions that contributed to the formation of the art colony: remote location, inexpensive models, the international phenomenon of art colonies and the social network of artists. She furthermore helps the reader to recognize socioeconomic changes that followed them, as Skagen became a tourist destination, but also the formal changes in the art, especially a shift to a brighter palette and extensive practice of plein-air painting. Jensen associates many of the changes with the arrival of Krøyer after 1882, whose extensive European travels exposed him to the camaraderie of art colonies in France and attracted a wider network of artists to Skagen (27–28).

One hopes that this offering by the National Museum of Women in the Arts will encourage further scholarship in the United States. Additional study will compliment, but also extend and challenge, the work already done by Fabritius and Jensen. Larsen’s question "Why Can’t Anna Be Modern?" remains inadequately answered. He urged scholars to consider her "avoidance of narrative, her rejection of the anecdote."[7] More direct analysis of how this element of Ancher’s work differs from the others in this exhibit would support the visual evidence generated in its display choices. While it is clear from the exhibition design that Ancher’s painterly handling of light and space stands out from her contemporaries in Skagen, Larsen suggested a comparison with more avant-garde artists in Denmark and in France, including Hammershøi. Larsen wrote in the 2009 catalogue:

There appears never to have been an exhibition in which Vilhelm Hammershøi and Anna Ancher have been placed side by side. But it could be beneficial, as in my opinion, they both aim for the same thing with their suspension of the narrative and the focus on the formal in the composition, the figure in the room etc. As the French painter Paul Signac put it, one of the most remarkable features of Modernism is that it abandons the anecdote for the line, analysis for synthesis, the transitory for the changeless.[8]

In fact, the 2009 exhibition did position Ancher next to Hammershøi and a catalogue essay by Guénola Stork suggested that their shared motif of empty interiors conveys “a sense of loneliness and melancholy” and “leads to a poetic evocation of a version of the intimate.”[9] The current exhibition in Washington, DC, however, neglects this comparison and rather looks backward from Anna Ancher, over her shoulder to those who immediately surrounded her. While Jensen’s 2009 exhibition, and Larsen and Stork’s catalogue essays, began to redirect examination of Ancher in light of other trends outside of Skagen, this does not really happen in the Washington, DC, show.

Indeed, it might be inappropriate for a show that is groundbreaking in the very introduction of the artist to also explode the frames in which we consider her. The curators followed good teaching practice and built schemata for future analysis of this artist, but missed some opportunities to build meaningfully on prior knowledge. While the comparison to Gauguin and possibly Hammershøi could easily have been meaningfully extended, a true evaluation of her modernist orientation would include more comparisons to Scandinavian artists, who like Ancher have not been as widely displayed or studied in the United States. Here, the curators might have made both more connections and raised more questions about how to view Ancher through references to last year’s American Scandinavian Foundation exhibit Luminous Modernism: Scandinavian Art Comes to America 1912 held in New York City.

In the current exhibit, the National Museum for Women in the Arts has attempted to correct the under-representation of Ancher and has issued a gentle call to consider this artist, recognizing that for most viewers, it is an inaugural encounter. The clear displays, narrative catalogue essays and thematic arrangement respected its audience and succeeded in opening doors to Anna Ancher’s expressive color and brushwork and to her “World Apart”. One expects that this groundbreaking American introduction to Ancher’s work will prompt exploration beyond light and color, but also the degree to which she refuted narrative and pushed radical abstraction in ways that far exceeded her Skagen colleagues.

Alice M. Rudy Price

Ph.D. Candidate, Temple University, Tyler School of Art

alice.price[at]temple.edu

[1] Grethe Holmen, “Anne Marie Carl-Nielsen and Anne Marie Telmànyi: Mother and Daughter,” Women’s Art Journal, 5, no. 2 (Autumn, 1984–Winter, 1985), 31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1357963 accessed 24 April 2013.

[2] See Gabriel P. Weisberg, Beyond Impressionism: The Naturalist Impulse (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1992).

[3] “Gauguin: Maker of Myth” exhibition organized by Tate Modern, London, in association with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, where it was on view February 27 through June 5, 2011.

[4] Anne Lie Stokbro, Anna Ancher & Co., de malende damer: Elever fra Vilhelm Kyhns tegne-og maleskole for kvinder 1863–1895 (Denmark: Ribe Kunstmuseum, Sophienholm og Johannes Larsen Museet, 2007). Anna studied at Vilhelm Kyhn’s school from 1875 to 1878.

[5] Peter Nørgaard Larsen, “Why Can’t Anna Be Modern?” in I am Anna: A Homage to Anna Ancher, ed. Mette Bøgh Jensen, trans. Walton Glyn Jones, exh. cat. (Denmark: Skagens Museum, 2009), 22–39.

[6] See Nina Lübbren, Rural Artists’ Colonies in Europe, 1870–1910 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001), 68–75.

[7] Larsen, “Why Can’t Anna Be Modern?,” 25.

[8] Ibid., 26.

[9] Guénola Stork, “The Reconquest of Space in Anna Ancher and Vilhelm Hammershøi—On the Verge of a Void,” in I am Anna: A Homage to Anna Ancher, 40.