The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Nel segno della Libertà, Gli artisti François (1784-1855) e Sophie (1797-1867) Rude

Museo Vincenzo Vela, Ligornetto, Switzerland

March 24–July 21, 2013

Catalogue:

Nel segno della Libertà, Gli artisti François (1784-1855) e Sophie (1797-1867) Rude.

With essay contributions from Claire Barbillon, Sophie Barthélémy, Lucile Champion-Vallot, Grégoire Extermann, Matthieu Gilles, Suzanne Glover Lindsay, Catherine Gras, Alain Jacobs, Wassili Joseph, Vera Klewitz, Isabelle Leroy-Jay Lemaistre, Éliane Lochot, and Gianna A. Mina.

Bern: Ufficio federale della cultura, 2013.

232 pp.; 190 color illustrations; 36 b&w illustrations; exhibition checklist; bibliography.

50 CHF

ISBN: 978-3-9523843-8-1

Exhibitions of, and research on, the work of both the sculptor François Rude (1784–1855) and the painter Sophie Rude (1797–1867, née Fremiet) have been long overdue. The previous exhibition of François Rude’s sculptures was held in 1955; a significant traveling exhibition of Sophie Rude’s paintings had never been realized before; and most of their works from Dijon have never left that city. Thus, it was with great anticipation that fifty-six stunning artworks created by this artistic married couple were elegantly displayed this past spring at the Museo Vincenzo Vela in Ligornetto, Switzerland. (Five additional works were included, created by their contemporaries.) The exhibition originated at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon, France, where it began its run with one hundred and ninety works in the fall of 2012.

Successfully representing the artworks of a married couple at exhibitions is a complicated task. One of the artists (usually the female, if it is a heterosexual couple) often receives less treatment, or seems a copyist of their conjugal counterpart. This did not occur at the Museo Vincenzo Vela, in part because François was a sculptor and Sophie was a painter, but also because great care was taken to give equal representation and scholarly attention to both artists. While there were many fewer works by Sophie Rude in the Ligornetto exhibition than those of her husband (only eight of the artworks shown were by Sophie Rude), a considerable effort was made to give her an equal presence throughout the exhibition and in the catalogue. This impartiality was felt immediately in the opening space, where tombstones equally presented the biography of each artist (fig. 1), and in the first room containing artworks, where the presentation begins with a portrait of François Rude by Sophie, and is bracketed, at the far end of the semicircular space, with her own self-portrait (figs. 1 and 2).

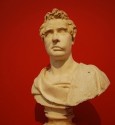

One of the obligations of the Museo Vincenzo Vela is to introduce examples of historically significant sculpture to the canton of Ticino and to produce scholarship that is accessible to an Italian-reading and -speaking audience. This mission was fulfilled nicely by Nel segno della Libertà. The exhibition was spread over ten galleries and was arranged thematically rather than chronologically. A lush red paint was used throughout to enhance the sculptures and paintings, which otherwise would have been set against white backgrounds, and red was also used on the pedestals, and in the wall label text to highlight titles and technical sculptural terms (such as primo bozzetto; maschera mortuaria; and monument finale): primo bozzetto (first sketch); maschera mortuaria (mortuary mask); and monument finale (final monument). The architecture of the Museo Vincenzo Vela is a quite stunning rotunda, and as one turns through the galleries, one often catches glimpses of subsequent sections of the show (fig. 3).

The first gallery focused on the artistic formation of both artists in their native Dijon. Two works stand out as particularly striking: Francois’s plaster portrait bust of the engraver Louis Gabriel Monnier (1762–1804), and Sophie’s painted self-portrait of 1841 (figs. 4 and 5). While certainly entrenched in the neoclassical style, the portrait bust of Monnier has the seeds of romanticism to come in the suggestion of a wind-swept collar, the pensive glance and the natural age and expression of the face. Strangely, the bust of his first teacher, François Devosge (1732–1811) created by Rude fifty years later in marble, seems comparably more stern, and has more of the pomposity and aloofness typical of the earlier neoclassicist style. Sophie Rude’s self-portrait is absolutely arresting, not only felt in the power of her gaze, which grips the viewer, but also in the fine skill with which she handled the brush and created the simulation of different textures of hair, lace and silk.

After the death of his father in 1805, Rude went to Paris where he studied sculpture and trained in the neoclassical style at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts under Edme Gaulle and Pierre Cartellier.[1] The persistence of the antique that continuously guided Rude’s work was the focus of the small second room (fig. 6). Examples of all aspects of Rude’s early training were presented here, including two drawings after the antique; an absolutely sparking small marble relief sculpture made in the year before his winning the Prix de Rome, entitled Winged Genius Sacrificing a Bull (1811, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon); a plaster pointed for transfer; and two bronze sculptures. An impressive bronze, Aristaeus Lamenting the Loss of his Bees (1830, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon), displayed in this room, takes a subject from classical Greek mythology (typical of neoclassicism) and shows the figure in a profound emotional state (typical of romanticism). Thus we perceive Rude’s working state of stylistic flux. The original clay Aristaeus, Rude’s winning 1812 Prix de Rome entry, was destroyed, but the bronze version displayed in Ligornetto was cast in 1830 by the founder Pierre-Maximilien Delafontaine (1774–1860), a painter who took over his family’s bronze foundry business after the death of his father (fig. 7). The modest Rude shared creative credit with Delafontaine, inscribing the work “Rude et Delafontaine 1830” on the base, as he did on Eurydice Gripped by a Serpent (1830, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon) and later when he shared authorship with his student Ernest-Louis-Aquilas Christophe (1827–92) on the tomb of Godefroy Cavaignac (1845–47, Montmartre Cemetery, Paris).

Both François and Sophie spent more than a decade in exile in Brussels after the Hundred Days of Napoleon I. While there, Sophie studied with the preeminent French painter Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), who was also in exile at the time. The third gallery presented two paintings by her, including the exquisite Portrait of a Young Lady (1849, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon) (fig. 8). While the work suffers from serious surface damage and paint loss (which has been carefully restored), the expressive, pensive face is clearly painted with a free brush, and does not have the overly stiff brushwork that is found in many canvases of David’s other students. Her work has more in common with Flemish and British portrait traditions, which is clearly evident when viewing the paintings, but which is also noted in Sophie Barthélémy’s essay in the catalogue on Sophie Rude as a portraitist.[2] A period piece depicting a scene from the Second Fronde War, entitled Encounter between the Prince and the Duchess of Montpensier (1834–36, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon) demonstrates Sophie Rude’s personal style; a rug-type table cloth at the far left of the painting shows a skill in tight, detailed brushwork second only to Jan Vermeer, while other passages have a more free application of paint. Encounter pairs nicely with François’s exquisitely detailed bronze bust of the constable of France under Louis XIII, Charles d’Albert de Luynes (1843–45, Musée des Augustins, Toulouse) who died in 1621. Two busts of David, one in plaster showing the artist in classical garb and the other in bronze and bare-chested, completed the gallery. Realized after David’s death, in both busts François Rude gives the elder artist the blank eyeballs seen often in busts of already deceased or revered figures, and handles the face with great sensitivity, despite the traumatic neuroma evident in David’s lower left cheek (fig. 9). A detailed essay by Alain Jacobs in both the Dijon and Ligornetto catalogues presents the Rude’s place within the artistic milieu of Belgium[3].

The theme of French history and national glory was presented in the fourth gallery, and concentrated on François Rude’s works (figs. 10 and 11). As many of Rude’s large-scale bronzes and marbles could not travel to Ligornetto, three small bozzetti (sketches) and one plaster bust were included here. However, to assist the visitor in comprehending differences between the early sketches presented in front of them with the final, large-scale works that were not physically on view, the museum included poster-sized, high definition images of the definitive works. Some of the finished works, such as that of Jeanne d’Arc Listening to Voices (1845–52, Musée du Louvre) remained faithful to the original ideas presented in the sketch with only minor changes. In other works, however, one sees enormous differences between the sketch and the finished work. The terracotta bozzetto for the statue dedicated to Maréchal Michel Ney (ca. 1850, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon) and its final version on the Avenue de l’Observatoire are quite different. The bozzetto shows a calm, reserved Ney standing quietly in a slight contropposto pose on a tooled but smooth ground; the final bronze depicts instead an emotive, dynamic Ney with arms in motion and his mouth wide open, calling his men to action. Other French national heroes represented by Rude were shown in this gallery and included a plaster bozzetto for his monument to General Henri-Gatien Bertrand (1846–53, Musée Hôtel Bertrand, Châteauroux), and a plaster bust of the statesman André-Marie-Jean Jacques Dupin the Elder (1838, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon).

In case the viewer was worried that the curators had forgotten about Sophie Rude, the next gallery proved their fears to be unfounded (fig. 12). Focusing on the theme of Rude as a talented portraitist, the gallery contained two paintings, created almost thirty years apart, and portraying her immediate relatives. The larger of the two works, a portrait Madame Van der Haert (born Victorine Fremiet, Sophie’s sister) is an oil on canvas that exemplifies Rude’s dexterity in handling paint. The large fur stole on Madame Van der Haert’s lap is specked with yellow, brown and even light blue, and the breeze-filled curtains just above her handsome face breathe palpable life into the painting. Ever so light touches of yellow highlight the curls of her hair. The second painting, a portrait of Rude’s nephew, Jean-Baptiste-Louis Van der Haert (1856, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon), exhibits similar meticulous details; the buttons and cords of his infantry officer uniform sparkle with flecks of yellow paint mimicking gold, and his hat shimmers with the greenish blue hue of peacock feathers. These two paintings alone demonstrate her skill, which was heretofore largely unknown and under-appreciated outside of Dijon. She exhibited her works frequently for almost fifty years at salons in Anvers, Brussels, Dijon, Gand and Paris.

One of the highlights of the exhibition was certainly among François Rude’s most famous works, the life-sized marble Young Neapolitan Fisher Boy Playing with a Tortoise (1831–33, Musée du Louvre). This influential romantic masterwork was displayed with three other objects (the bronze Eurydice Gripped by a Serpent mentioned earlier; a plaster head study for his Hebe, and a portrait of Rude’s student, the sculptor Paul Cabet, by Sophie Rude) in the sixth room (fig. 13). While this gallery did not have a clearly stated theme, the two main sculptures fall into the period just before Rude began his most famous and significant sculpture, The Departure of the Volunteers in 1792, better known as “La Marseillaise,” the subject of the gallery that was to follow. The Young Neapolitan Fisher Boy was installed at eye level, which allowed the viewer to really analyze the surface of the marble and other details (fig. 14). The three different objects on the ground where the boy sits include his fishing net, a sandy shore, and the delicate waves of the beach at low tide; these are all carved with an obsessive attention towards realistic detail. One can almost pinpoint the start of the romantic style in sculpture to the Salon of 1831 in general and this sculpture, exhibited there, in particular. Looking at the sculpture from such a close range allowed for essential details, such as the weave of the fisher boy’s hat or the pulled skin of the neck of the turtle, to emerge. The boy wears a devotional scapular with a faintly carved image of the Virgin, another small detail that, once noticed, deepens the meaning of the sculpture: this mischievous boy, who practically chokes the little tortoise to death, is still an innocent child, vulnerable, naked, and shielded by the motherly protection of the Virgin.

The entire seventh gallery was devoted to the Arc de Triomphe and specifically to François Rude’s bozzetti for The Departure of the Volunteers in 1792, also known as “La Marseillaise” (fig. 15). In addition to plaster models for the head and the full pose of the Allegory of the Republic, the room included plaster sketches for the full composition. The most interesting of these was called the “second version bozetto”, in which we can see that Rude’s earlier concept had fewer figures, was dominated by a large Marly horse and a nude soldier, and contained a somewhat less dramatic allegorical figure (fig. 16). The center of the room was dominated by a very detailed plaster model by Georges-Paul Chedanne (1861–1940) of the completed Arc de Triomphe. The museum provided a very useful card to be used in the gallery to help in identifying all of the different parts of the structure, the subjects covered on it in relief, and the sixteen sculptors who worked on various aspects of the Arc’s sculptural program. The Departure of the Volunteers in 1792 is the supreme example of a romantic sculpture placed on a public monument that was otherwise entrenched in a neoclassical tradition. A detailed essay by Wassili Joseph in both versions of the catalogue discusses the evolution of the Departure of the Volunteers in 1792.

A long corridor that the Museo Vincenzo Vela often uses to display drawings contained fourteen works on paper, most relating to the decoration of the hunting lodge of the Prince of Orange at Tervueren (fig. 17). Both François and Sophie worked on this project together. He developed bas-reliefs for two series, one dedicated to the life of Achilles and the other focused on the Hunt of Meleagro; she developed four concepts for allegories of music.[4] The fourteen drawings, even those of the allegories to music, were all attributed to François Rude, and reflected his romantic (that is, modern) approach to classicism. As the Tervueren hunting lodge was destroyed by fire in 1879, these drawings are an important testament to the project and to Rude’s most significant work completed in Brussels.

The theme of monuments to French heroes continued in the ninth of the exhibition (fig. 18). This room included bozzetti for a monument to Jean-Antoine Houdon and to Gaspard Monge. Visitors were directed to compare Rude’s monument to Nicolas Poussin, represented here by a 1:2 scale reduction (1854, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon), to Vela’s Monument to Antonio Allegri da Correggio (1879–80, Museo Vinceno Vela, Ligornetto), located in the permanent collection on the first floor (figs. 19 and 20). Both artists are depicted in the garments of their time, captured in a moment of inspiration, and continue a tradition of artists depicting their most admired predecessors.

Images dedicated to sleep and her sister, death, were appropriately placed in the final, tenth room (fig. 21). While Rude’s life-sized bronze for the tomb of Godefroy Cavaignac (1847/1891, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon), and his bronze Napoleon’s Awakening to His Immortality (1847, Parc Noisot, Fixin) could not be installed at Ligornetto, a wonderful, dark green cast of Rude’s funerary project for Napoleon’s tomb (ca. 1840–47, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon) was presented with Frencesco Antommarchi’s death mask of Napoleon (1821/1833, Musée Noisot, Fixin). What Rude could not realize in a tomb to Napoleon comes into being with his tomb of Cavaignac, and the photo of the Cavaignac bronze assists the viewer in seeing the vast influence of the earlier Napoleon project on the later tomb. Following the theme of memorials, the exhibition presented on the second floor ended with Paul Cabet’s bronze bust of François Rude (1852–55, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon), a bronze cast similar to that atop a monument dedicated to Rude at Fixin (fig. 22). When the visitor at Ligornetto turned to view Cabet’s work, the first room of the exhibition, with Sophie Rude’s portrait of her husband, comes back into view (fig. 23). This was a splendid way to literally come full circle and complete one’s experience of the exhibition.

François Rude’s over life-sized bronze Mercury Fastening his Sandals (1834, Musée du Louvre, fig. 24), was placed on the first floor of the museum because of its size. This grand, dynamic sculpture, with its dramatic serpentinata (serpentine form) was Rude’s first Salon success, and was an homage to great Italian sculpture of the Renaissance. As the plaster version was shown in the Paris Salon of 1827, it also marked François Rude’s official reentry into Parisian society after his long exile. While it was easy to miss if the visitor started the exhibition on the second floor, it could be seen from the second-floor overlook (fig. 25). The darkly patinated bronze, with its touches of gold gilding, looked stunning against the background of Vincenzo Vela’s monumental plasters and sculptural busts in the permanent collection.

The Ligornetto version of the exhibition catalogue republished in Italian many of the essays from the Dijon publication. Together they present significant new research that covers a full range of information on each artist and include sections on the artists’ formative years in Dijon and Paris (with essays by Éliane Lochot, Matthieu Gilles and Wassili Joseph); their years in exile in Brussels (Alain Jacobs, Wassili Joseph, and Lucille Champion-Vallot); their return to Paris and their successes at the Salon (Isabelle Leroy-Jay Lemaistre, Sophie Barthélémy); the evolution and influence of the Departure of the Volunteers in 1792 (Wassili Joseph, Claire Barbillon, and Sophie Barthélémy); the taste for images of glory and national heroes (Vera Klewitz, Catherine Gras, Susan Glover Lindsay); and the artistic testament of François Rude (Wassili Joseph, Catherine Gras). An essay on the links between images of Napoleon I by Rude and Vincenzo Vela by Grégoire Extermann was published only in the Ligornetto catalogue, and the Dijon catalogue contains four additional essays that do not appear in the Ligornetto version, on Sophie Rude’s Davidian inspiration (Sophie Bathélémy); women painters of Brussels (Alexia Creusen); and essays on the couples’ religious-themed works (Sophie Jugie, Vera Klewitz). Both contain fully illustrated catalogues of the images shown at their specific venues with specific information on provenance, previous exhibition history for each object, and detailed bibliography for each object. Finally, both publications contain an excellent, up-to-date bibliography.

Both publications and the exhibition in Ligornetto solidified François Rude’s important role as the originator of romanticism in French sculpture, and provided an excellent and much needed introduction to the paintings of Sophie Rude. Nel segno della Libertà, Gli artisti François (1784–1855) e Sophie (1797–1867) Rude was excellently displayed at the Museo Vincenzo Vela and introduced this French artist-couple to a new audience in southern Switzerland.

Caterina Y. Pierre, PhD

City University of New York at Kingsborough

caterinapierre[at]yahoo.com

caterina.pierre[at]kbcc.cuny.edu

Related Links

Mendrisio Cultural Service Website:

http://www.mendrisio.ch/780/servizi-amministrativi/museo-e-attivit-culturali/museo-vincenzo-vela/museo-vincenzo-vela-di-ligo

Museo Vincenzo Vela, press release:

http://www3.ti.ch/DECS/sw/temi/osservatorio/files/doc/1604_CS_VELA_Rude.pdf

20 Minuti online:

http://www.tio.ch/News/Ticino/726518/Il-gigantesco-Mercurio-dal-Louvre-al-Museo-Vincenzo-Vela/

Museo Vincenzo Vela, Ligornetto

http://www.bundesmuseen.ch/museo_vela/index.html?lang=it

Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon

http://mba.dijon.fr/

I wish to express my thanks to Dr. Gianna A. Mina, Director of the Museo Vincenzo Vela for her helpful suggestions and for permitting me to photograph the exhibition for this review.

[1] For an overview of Rude’s formative years in Paris, see Wassili Joseph, “Gli anni di formazione di Francois Rude a Parigi: il culto dell’antico,” in Sophie Barthélémy, Matthieu Gilles e Gianna A. Mina, eds., Nel segno della Libertà, Gli artisti François (1784–1885) e Sophie (1797–1867) Rude (Bern: Ufficio federale della cultura, 2013), 34–43. The same essay is found in the Dijon version of the exhibition catalogue, with the title “Les années de formation de François Rude à Paris: Le culte de l’antique.”

[2] Sophie Barthélémy, “Sophie Rude, ritrattista,” in Sophie Barthélémy, Matthieu Gilles e Gianna A. Mina, eds., Nel segno della Libertà, Gli artisti François (1784-1885) e Sophie (1797-1867) Rude, 90. The same essay is found in the Dijon version of the exhibition catalogue, with the title “Sophie Rude, portraitiste.”

[3] Alain Jacobs, “La coppia Rude-Fremiet e la scena artistica belga (1815–1829),” in Sophie Barthélémy, Matthieu Gilles e Gianna A. Mina, eds., Nel segno della Libertà, Gli artisti François (1784–1885) e Sophie (1797-1867) Rude, 46–55. The same essay is found in the Dijon version of the exhibition catalogue, with the title “Les rapports du couple Rude-Fremiet avec le milieu artistique belge (1815–1829).”

[4] For a discussion of Sophie Rude’s role in the decorative program of the Tervueren Hunting Lodge, see Wassili Joseph, “Le decorazione del padiglione de Tervueren, il capolavoro neoclassico di François Rude,” in Sophie Barthélémy, Matthieu Gilles e Gianna A. Mina, eds., Nel segno della Libertà, Gli artisti François (1784-1885) e Sophie (1797-1867) Rude, 59. The same essay is found in the Dijon version of the exhibition catalogue, with the title “Les décors du pavillon de Tervueren, le chef-d’œuvre néoclassique de François Rude.”