The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Picasso and the Mysteries of Life: La Vie

December 12, 2012–April 21, 2013

Museu Picasso

Barcelona, Spain

October 10, 2013–January 19, 2014

As Raphael Viñoly’s redesigned building for the Cleveland Museum of Art comes to completion, new galleries are being opened and the collection reinstalled. The Focus Gallery is to be a permanent experimental venue featuring the comprehensive study of a single work in the collection accompanied by a scholarly catalogue. The inaugural exhibition for this concept is Picasso’s (1881–1973) important Blue Period painting of La Vie (1903) with the accompanying catalogue authored by the curator of modern painting, William H. Robinson. It contains new research as well as discussion of the under painting discovered from the X-radiograph.[1] This review examines the pedagogical success of the installation independent of the catalogue.

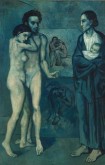

The installation is complicated by glass wall entrances from two sides, one the main entrance hallway, and the other a corner entrance from the museum’s cavernous new atrium, where a billboard size title announces the exhibition (fig. 1). The hallway leads to a large open gallery, which offers a line of vision to La Vie, which dominates the gallery by virtue of its size and “wall power” (to use a favorite phrase of former director, Sherman E. Lee). It is flanked by study drawings for the painting from the Museu Picasso in Barcelona, which will be a second venue for the exhibition (fig. 2). Visitors accessing the show through the corner entrance are presented with a small display of four tarot cards with an accompanying label that explores possible links to Picasso’s painting (fig. 3). Next, along the back wall of the center entrance, a large welcoming label offers introductory remarks about the painting, stating the intention of exploring the identity of individual figures to understand broader issues relating to modern bohemian culture (fig. 4). The statement that the meaning of the painting “continues to baffle scholars today” would seem to discourage spending any further time in the gallery, and to discount the years of study clearly evident from the catalogue, and in the collateral sculpture and graphic art in the gallery.

Picasso’s painting is linked to February 1901 when his poet/painter friend, Carles Casagemas, committed suicide (fig. 5). Casagemas was in love with the artists’ model, Germaine Pichot, who rejected him as impotent. Picasso was in Madrid when Casagemas, while dining with friends in Paris, shot at Pichot who fell under the restaurant table unharmed. Thinking he had killed her, Casagemas then took his own life. Mortality preoccupied these teenagers (all three were nineteen) and Picasso in particular, from van Gogh’s suicide in 1890 to the death of his younger sister from diphtheria five years later. Gauguin attempted suicide in 1897, the same year another artist-friend of Picasso, Hortensi Güell, took his life. Picasso pursued the subject of death in two drawings of Güell and his grieving colleagues. Nietzesche’s death in 1900 was followed by that of Gauguin in May 1903 when Picasso began La Vie (fig. 6).

Along the major entrance wall, the label next to Picasso’s pastel of a tavern scene (ca. 1899) identifies the young woman in La Vie as Pichot, who also becomes the fatal woman in Picasso’s pastel. Casagemas made an ink drawing of a more recognizable Germaine Seated in a Café (ca. 1900) (not shown in the exhibition). To further underscore Pichot as a late nineteenth century femme fatal, Edward Munch’s lithograph of Sin initiates the left wall, the woman’s long hair cited as a signifier of her sexual allure. As one follows this wall toward the painting, a vitrine displays Théodore Rivière’s marble carving of Chastity (ca. 1900, not illustrated in the catalogue) personified as a female nude enveloped in billowing drapery, her ankle length hair suggesting that long hair might also be a sign of virtue. Next, Picasso’s two conté crayon drawings of couples appear preliminary to the pair in the painting. Following these are Picasso’s portrait drawings of Casagemas, and an oil portrait of 1899, the accompanying label explaining the poet’s frustrated love, and his failed attempt to shoot Pichot followed by his suicide. Picasso’s pencil portrait shows Casagemas as naked and defensive. The artist’s images of him are both playfully mocking and brutally honest, and reveal a complicated friendship.

Next are two drawings for Poor Geniuses, which deal with Güell mourned by his friends. These are preceded by a label that announces Güell’s suicide. Melancholy, artistic poverty, elusive success, and frustrated expression seem to characterize the early careers of these young artists, apparently complicated by frequent testosterone surges.

The back wall to the left of La Vie displays two of Picasso’s study sketches in conté pencil of the artist and his nude model plus an easel and an old man, both sheets (like all the others) from the Museu Picasso in Barcelona. Pointing gestures are given some importance in these drawings, which link them to the equivocal gesture of Casagemas in the painting, where he has replaced Picasso as protagonist of the drawings. The old man’s pose is like that of a bearded man in one of the three Barcelona drawings to the right of the painting, which is a portrait of the sculptor Emili Fontabona. Picasso eliminated himself and Fontabona from the painting to honor his dead friend, Casagemas, instead. The other drawings are a Nude Woman and a Woman with Two Children. These are linked to the two women in La Vie.

Two tablet size video screens at the left of the painting display infrared and X-ray images from the under painting (fig. 7). Displayed vertically, these nicely highlight details in outline on command from the viewer for clearer legibility, but perhaps one should be placed horizontally to better display the original painting. Two additional pedestals in the gallery contain sculptures. One displays Rodin’s marble Fall of Angels (ca. 1890), in which the winged figure falling backward is mimicked by Picasso’s Bird Man in the X-ray (fig. 8).[2] In a glass-encased vitrine, Rodin’s small bronze The Damned of two embracing women, and his bronze Young Girl Confiding Her Secret to Isis (1899) are joined with Baudelaire’s book, Flowers of Evil, opened to the poem Jewels, which laments the decadence of the modern world (fig. 9). These relate to the embracing women in the top center background of La Vie.

On the right wall a label clarifies the winged figure or Bird Man from the X-ray, which is more clearly revealed in the infrared reflectogram. He hovers over a sensual woman. A palimpsest of her outline is visible in the painting. She seems to welcome his presence, rather than recoiling in terror as concluded from initial X-ray examinations. Picasso’s two drawings of winged figures, one male, another female, depict both as benign. With spread arms and open palms, they embrace figures below them in a fashion reminiscent of the expansive gesture of Christ in Leonardo’s Last Supper. These sheets from the Museu Picasso continue along the right wall as the viewer moves back toward the entrance. Picasso’s oil of 1903, Allegory of Fortune, is followed by a pencil and ink drawing, Palm Reading of Picasso’s Left Hand, which references palm reading with a text by his life long friend, the French poet Max Jacob (1876–1944), and a chart of the artist’s hand.

Following these works is a little tempera panel by Bicci di Lorenzo (ca. 1430), stressing the play on hands with Saint Francis receiving the stigmata from Christ as a winged seraph. Red lines link the hands of the two figures.[3] Next, two etchings by Goya, one of men with bat wings, and the other a giant owl flapping its wings over a bound couple offer possible sources for Picasso from his stay at the Academy of San Fernando in 1897–98. The first, Proverb: A Way of Flying (1815/1820) indicates flights of the imagination or nightmares rather than Leonardo’s flying machines (fig. 10). The other, Can’t Anyone Untie Us, pursues a popular theme of Goya, namely the inseparability of good and evil within the individual.[4] Finally, Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I (misspelled as “Melancholia” on the label) is given as indicative of the artist as “prone to madness and suicide,” rather than reflective traditionally of the elusiveness of ideas, a theme more appropriate to the frustrated subject revealed in the X-ray (fig. 11).[5]

The viewer is now back at the entrance wall with the tarot cards and three poster enlargements of the drawing of Picasso’s hand, his painting of a woman with arms spread (Allegory of Fortune), and the grainy Bird Man from the infrared reflectogram (see fig. 4). Without labels they are only understood on exiting, and might even be missed when entering by the center door. They serve as blow-up reminders of the smaller original works related to Picasso’s abandoned false start.

Picasso pursues arm, hand, and pointing gestures in several of the drawings which coalesce into Casagemas’s timid left index finger in the painting. From Picasso’s drawings we see the orans pose of one of the males, his arms extended in another sheet, the spread arms with open palms in the winged figures, the pencil drawing of a recumbent woman displaying darkened palms, and the 1902 drawing of the palm reading of Picasso’s left hand. Emphasis on the open palm as a sign of life’s suffering, much as the nail wounds in Christ’s hands were evidence of His passion, is suggested only to be abandoned in the end. These studies are irrelevant to the final painting.

A wall label left of La Vie alludes to the gestures in Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling Creation of Adam, but they represent just one example in a whole vocabulary of pointing gestures in earlier art, from the Baptist’s identifying Christ to the apostles, to the Noli Me Tangere, the Doubting Thomas, and to Savonarola’s pointing skyward to the Ara Pacis in his sermons as inspired by Virgil, Revelations and the Mirror of Salvation. These gestures make sense because they have an iconography. The challenge is to find the context for Casagemas’s gesture in La Vie.

Topics explored in the catalogue, but not readily amenable to display, include Robinson’s revealing discussion of the Saint-Lazare Prison for women which touches on issues of prostitution, pregnancy, venereal disease, and addiction as related to the melancholy life of the female model.[6] The other subject involves Picasso’s access to Gil Blas Illustré, the weekly supplement to the French daily newspaper, Gil Blas. Picasso’s pencil drawing of his father (not exhibited) depicts him in a great coat with a copy of Gil Blas in his pocket, the by-line clearly, and it would seem, deliberately indicated. The weekly supplement frequently included color illustrations of artists’ studios, artists’ dalliance with models, and cartoons of Bohemian life. Picasso was fascinated with Théophile Steinlen’s illustrations for the magazine, which delineated his milieu.[7] Although available for loan from the Cleveland Public Library, no copies of Gil Blas Illustré were on display because the gallery space was not adequate to accommodate the large sheets. It will be interesting to see if any appears in the Barcelona venue.

The treatment of tarot cards is slighted in the exhibition, and appears almost as an after thought, and perhaps appropriately. If Picasso was intrigued by them in the context of palmistry, he quickly abandoned this path that was leading nowhere, and does not manifest itself in the final painting.[8]

The man in La Vie is no longer Picasso who has been painted over, but the impotent painter/poet Casagemas, frustrated in love, timidly pointing to the family that would elude him, the child he would never have, and the mother Pichot would never be. His gesture leads the viewer’s eye across the stacked paintings at the center background, perhaps of a pair of lesbian lovers at the top, one possibly Pichot, and the other of a lone sorrowing woman, perhaps Pichot again. She might be the woman embracing Casagemas to show her affection for him, Picasso salving her conscience now that she had become his lover, the artist allegorizing his art, his art allegorizing life.

Blue may be the color of melancholy, but traditionally it is associated with folly by Pieter Brueghel and Bronzino, and with Venus by artists from Titian and Pontormo to Picasso in his Demoiselles d’Avignon.[9] Picasso explained the color sixty years later (ca. 1965) to his friend, Pierre Daix: “It was thinking about Casagemas’s death that started me painting in blue.”[10] Whether blue as indicative of melancholy or of the folly of Casagemas’s suicide, the artist leaves open to speculation. If nothing else, Picasso is explicit that La Vie initiated his Blue Period.

The X-radiograph matrix discovery of the under painting in 1976, three years after Picasso’s death, revealed the original horizontal painting, Last Moments, that Picasso exhibited in Barcelona in 1899.[11] The subject and composition are known from drawings and a description of February 3, 1900 in La Vanguardia.[12] A priest with a prayer book stands left of the bedside of a dying woman covered by a white quilt reflecting the light of a lamp (fig. 12). The white glow at the bottom of the X-ray is the lamp, and the geometric shape to its left is the bed stand on which it rests, more evident when the X-ray is rotated counter clockwise by ninety degrees. Little else is visible because the subject was a tenebristic exercise in the tenor of his barely legible oil on the left wall, At Dead Man’s Side, 1899–1900, Museu Picasso.

After the Paris Exposition of 1900, Picasso exhibited for Ambroise Vollard in a three-week show, June 25–July 14, 1901.[13] The Galerie Vollard venue was successful with a number of sales and mixed but supportive reviews. The poet Felicien Fagus noted stylistic influences of the Nabis, Delacroix, Manet, Toulouse-Lautrec, Degas, van Gogh, concluding; “One sees that Picasso’s haste has not given him time to forge a personal style.”[14] He encouraged the artist for his “youthful, impetuous spontaneity” and “brilliant virility.” The point was taken, and it was from this time that Picasso began to reuse his canvases.[15] The Cleveland canvas, Last Moments, was a prophetic title as the painting became expendable.[16] In a vertical format it offered the support for a new work, La Vie. The Bird Man and reclining woman represent a second stage, a false start never completed, a fraction of a painting intermediate between Last Moments and La Vie.[17]

Non-invasive scientific techniques such as X-radiation and infrared reflectance spectroscopy offer another type of art historical methodology for analyzing paintings. They show us something of how the artist choreographed his composition, and how changing content dictated the tectonics of his painting. The touch screens fascinate, allowing the viewer to share these secrets hidden for decades. The X-ray images and the related drawings support each other in a reciprocal way. They indicate how the artist started, and how he developed his ideas along the way, only to abandon them in the end. It is the finished painting that reveals what Picasso intended. He admitted as much when he stated, “I simply painted images that arose in front of my eyes; it’s for others to find a hidden meaning in them. A painting for me speaks by itself.”[18]

The pigmented surface of a painting is a laminate in a limited sense. That is, it consists of layer upon layer of pigment applied brush stroke by brush stoke, some with the same pigments. These meld into the painted surface on the prepared canvas as the pigments dry. X-rays are capable of penetrating this surface. In the process, they detect some pigments, but others elude them. No non-invasive technique has yet been developed to allow the examiner to recreate this painted surface brush stroke by brush stroke to follow an artist’s progress as he makes revisions. Consequently, the “laminate” for the most part remains an integral painted surface.

The exhibition gives much attention to a clarification of the blurred under-painting only grudgingly revealed by the X-ray. Whereas X-rays show under paint hidden to the naked eye, they only display lead-based pigments, and so miss corrections made with non lead-based pigments. The danger in reading X-rays, then, stems from this fact that radiation only detects lead, usually white lead oxide (PbO), which is often mixed with other pigments to create tints of colors. These reveal themselves in the radiograph matrix as the white areas opaque to radiation, such as the bright lamp in Last Moments. Non lead-based pigments, which the artist might add to modify some detail would not be visible. They would appear as dark areas in the X-ray, and therefore would not show modifications by the artist. Thus, it is possible that details might have been changed as Picasso worked on the painting, the artist making corrections as he progressed, so that even he might not recognize details from the X-ray. For example, he could have reworked the sensuous lips of the woman greeting the Bird Man to a scream with a non-lead-based pigment that would not be revealed in the X-ray. The X-ray “sees” only some things the human eye does not. In the end, the eye sees more, and sees only what the artist wants it to see. Picasso rejected most of the exploratory drawings on view just as he buried his false leads on the canvas. Most of the Barcelona drawings represent ideas that never materialized. Of the 36 support images exhibited, fifteen relate to the X-ray, and fifteen to La Vie. The under painting is useful to reveal something of the development of Picasso’s thinking as he worked on the canvas, but the meaning of the painting lies on its surface. In painting, it is the superficial that takes precedence.

Nonetheless, some remnants of the early studies remain, such as the artist/model pairing, the pointing gesture, and the central paintings, with Casagemas and Pichot replacing Picasso and his generic model from the drawings and X-ray, with the stacked canvases preserving the milieu of the artist’s studio. Picasso substitutes the sculptor Fontabona with the woman and child in the process, changing the tenor of the composition from the professional context of artist to a more personal statement of the life (La Vie) that Casagemas would never have, a combination of his impotence and the folly of his suicide. Picasso gave the Cleveland painting its title, La Vie, within days of its completion. To title a painting at all was rare for the artist, although less rare in these early years as a gallerist.[19] That he did not title it Le Mort suggests that for Picasso it represented an affirmation of life through his art.

Shadows confirm the palpability of the body that casts them as it interrupts the flow of light. They are also directional indicators and help to define space. The shadow cast by Casagemas’s leg does not fall on the paintings behind him, but rather slips under that resting on the floor suggesting already an incipient attitude to pictorial space in the direction of cubism.

As the maiden voyage of The Cleveland Museum of Art in visual scholarship, the Focus Gallery is an engaging success for alerting the public to the kinds of questions to be raised about a work of art, while also revealing the limitations of art historical research that advances more through consensus than by the exactitude of the physical sciences. The Focus Gallery offers an agreeable substitute to the defunct Bulletin of The Cleveland Museum of Art as modern technology pushes the print medium into gradual obsolescence (although a catalogue remains indispensable). The public can look forward to the next stimulating study of a master work of art in the vast collection of the institution when the Picasso display moves on to Barcelona.

Edward J. Olszewski

Case Western Reserve University

ejo[at]po.cwru.edu

[1] For previous studies of this painting, see Marilyn McCully and Robert McVaugh, “New Light on Picasso’s La Vie,” Bulletin of The Cleveland Museum of Art, 65/2 (February 1978): 66–71; William Robinson, “The Artist’s Studio in La Vie, Theater of Life and Arena of Philosophical Speculation,” in Picasso, The Artist’s Studio, ed. by Michael Fitzgerald, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001) 63–87; Becoming Picasso, Paris 1901, ed., Barnaby Wright (London: The Courtauld Gallery, 2013).

[2] For the Bird Man, Picasso probably did not know Alfred Gilbert’s bronze Icarus of 1884 in Wales, but he could have been familiar with a winged Assyrian demon deity, the apotropaic bronze of Pazuzu in the Louvre, where he studied ethnic sculptures (even absconding with a few); see Bronze, ed., David Ekserdjian (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2012), 97, fig. 93 for Gilbert, and 39, fig. 32 for the Assyrian winged deity. For his interest in ethnographic imagery, see James Sweeney, “Picasso and Iberian Sculpture,” Art Bulletin, 23, no. 3 (September 1941): 191–98. The authoritative source for this phase of Picasso’s career is, John Richardson, A Life of Picasso (New York: Random House, 1991)

[3] The painting was removed on February 4, 2013, for another in-house exhibition; see the catalogue illustration in Stephen Fliegel, The Caporali Missal, A Masterpiece of Renaissance Illumination (Munich: Prestel, 2013) 112–13, no. 16.

[4] For Goya’s inseparable pairings, see Edward Olszewski, “Goya’s Ambiguous Saturn,” in Twenty-First-Century Perspectives on Nineteenth-Century Art, Essays in Honor of Gabriel P. Weisberg, eds., Petra ten Doesschate Chu and Laurinda Dixon (Newark, NJ: University of Delaware Press, 2008), 129.

[5] Erwin Panofsky developed the iconography for Melencolia I as a specific type of melancholy alluding to the allusiveness of abstract ideas, a theme appropriate to La Vie, given how Picasso was unable to finalize the Bird Man subject; The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press: 1955), 156–71, esp. 163.

[6] That the model’s situation might not always be so bleak, see Marie Lathers, Bodies of Art, French Literary Realism and the Artist’s Model (Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), esp. “The Model’s Postpartum Belly,” 169–93, a mark of some of the models in Picasso’s drawings.

[7] Richardson reports this interest in A Life of Picasso, 126, note 2.

[8] Richardson’s esoteric discussion of Picasso’s interactions with tarot cards and palmistry may explain why his pursuit of this interest never extended beyond the few drawings (as in note 2), 270–75.

[9] For blue and folly, see Walter Gibson, Bruegel (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd., 1977) 71–78. For Venus, see Maurice Brock, Bronzino (Paris: Flammarion, 2002), 212–37. In Bruegel’s painting, Netherlandish Proverbs, of 1559, also called The Blue Cloak, an adulterous wife clothes her deceived husband with a blue cape. Frans Hogenberg’s etching of 1558 contains an inscription that reads, “This is generally called the Blue Cloak, but it would be better named the world’s follies.” Venus is consistently depicted as reclining on blue fabrics. Mario Equicola noted that the French thought blue (ceruleo) denoted jealousy in Libro di Natura d’Amore (Venice, 1526), 164r. Raffaello Borghini noted that “blue signifies beauty,” but also that for the common people it represented jealousy, Il Riposo, ed. Lloyd Ellis, Jr. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press: 2007), 151, 155. Blue could also allude to the sea from which Venus was born; see Vincenzo Cartari, Le Imagini de i dei de gli Antichi, eds. Ginetta Auzzas, Federico Martignago, Manlio Stocchi and Paola Rigo (Vicenza: Neri Pozza Editore, 1996), 464.

[10] “C’est en passant que Casagemas était mort que je me suis mis à piendre en bleu” as quoted in Pierre Daix, La Vie de Peintre de Pablo Picasso (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1977), 47; Picasso: Life and Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 1933), 27. Richardson, 182. In late 1901, Picasso visited the women’s prison of Saint-Lazare noting the blue uniforms worn by the inmates, many with children, with those afflicted by venereal disease required to wear white bonnets. This resulted in studies and paintings of women in blue, mother and child, women drinkers in blue with white caps. Possibly, the institutional blue signified confinement for Picasso. His use of the color may have originated when he observed the reflection of his friend, Jaime Sabartés, sitting in a bar with blue mirrors whose portrait he painted (Le Bock). Sabartés commented, “Regarding myself for the first time in that marvelous blue mirror which to me is like a vast lake whose waters contain something of myself.” See Marilyn McCully, “French Origins of the Blue Period,” in Picasso in Paris 1900–1907, ed. Michael Raeburn (London: Thames & Hudson, 2011), 97. For Anthony Blunt and Phoebe Pool, “The key picture of 1903, and perhaps of the whole Blue Period, is La Vie,” as quoted in Picasso, The Formative Years: A Study of his Sources (New York Graphic Society, 1962), 20

[11] It was exhibited at Picasso’s favorite Barcelona tavern, Els Quatre Gats, and in Paris in the Spanish Pavilion at the Grand Palais for the Exposition Universelle in 1900. See Richardson, 145, 148, 149, 172.

[12] McCully and McVaugh (as in note 1), 67–71; Richardson, 123.

[13] McCully marveled that he made 64 works in five or six weeks, but Vollard later (ca. 1936) recalled Picasso showing him 100 works in early 1901 in solicitation for the exhibition. See Marilyn McCully, “Picasso’s Artistic Practice in 1901” in Becoming Picasso, 58, n. 10.

[14] Cited in C. F. B. Miller, “The Formation of Genius,” in Becoming Picasso, 98, from Felicien Fagus, “L’Invasion Espagnole: Picasso,” La Revue Blanche, July 15, 1901.

[15] It was after 1900 that Picasso began to reuse his canvases, all from his Barcelona studio, a practice that he continued until 1908. Richardson denied any connection between Last Moments and La Vie, and claimed that, “The link in subject matter is coincidental,” as quoted in Richardson, 123, 275. Picasso considered the Cleveland painting as a new phase.

[16] The critic Gustave Coquiot wrote a favorable review and became a friend of the painter who presented him with a portrait (Centre Pompidou). The title of his review, “La Vie Artistique: Pablo Ruiz Picasso,” Le Journal, June 17, 1901, may have inspired the metonymic title, La Vie.

[17] Marilyn McCully, “Picasso’s Artistic Practice in 1901,” in Becoming Picasso (as in note 1) 51, 53, 56–57.

[18] Richardson, 275.

[19] Richardson, 273.