The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Oil and Water: (Re)Discovering John Frederick Lewis (1804–76)

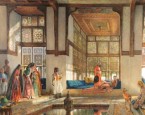

Sometime in 1878, or perhaps a bit earlier, Abel Buckley (1835–1908) acquired a watercolor painting by John Frederick Lewis (1804–76).[1] The decision was not in itself remarkable: Buckley was a prominent collector in industrial Manchester, and had already amassed an impressive, if eclectic, collection of modern British art in his home, Ryecroft Hall.[2] And yet the particular picture that Buckley chose to purchase was noteworthy indeed. It was a larger version of an oil painting called A Lady Receiving Visitors (The Reception) (1873, Yale Center for British Art), one of Lewis’s most provocative late Orientalist works (figs. 1, 2).[3] The rediscovery of this elusive watercolor in 2007, and its instructive potential vis-à-vis the Yale work, are the subjects of this article.

Though less well known today than its oil counterpart, Lewis’s watercolor was widely publicized in the 1880s. By 1887, it was attracting attention at Manchester’s Royal Jubilee Exhibition, an extraordinary celebration of that city’s modern art collections, and in particular, of watercolors in private hands.[4] This was, in fact, the second time Buckley had lent The Reception to such a significant local cultural event.[5] In 1878, it was exhibited at the Royal Manchester Institution—its first recorded appearance since Lewis painted it in 1873.[6]

In 1891, the watercolor appeared in London, at the Royal Academy’s winter exhibition of Old Masters and "Deceased Masters of the British School."[7] Its owner was now listed as the well-known philanthropist and collector Stephen George Holland (1817–1908). A regular lender to the Royal Academy, as well as to other venues, Holland lent the picture again in 1898, this time to a special exhibition at the Royal Water-Colour Society Art Club honoring present members and "the late J. D. Harding and the late J. F. Lewis."[8] It was here that Lewis’s watercolor might have caught the eye of several prominent London dealers with a penchant for Lewis, and a taste for the exotic.

Despite his London address, Holland’s professional background, aesthetic taste, and spirit of benevolence were not radically different from Buckley’s own. Holland too had turned his attention to contemporary British art after making his money in business.[9] His collection, which eventually numbered over 140 watercolors and oil paintings, became one of the most talked about in London at the turn of the century.[10] In addition to The Reception, Holland owned several of Lewis’s best-known oils, including A Kibab Shop, Scutari, Asia Minor (exh. R.A. 1858), A Turkish School in Cairo (exh. R.A. 1865), and A Cairo Bazaar, the Della’l (exh. R.A. 1876).[11]

Perhaps because Lewis was a favorite of Holland’s, The Reception was one of a handful of works to remain with the family after his death and the subsequent sale of the collection by Christie, Manson & Woods in June 1908.[12] The circumstances of the family’s continued ownership, however, were not entirely straightforward: the picture was purchased at the sale by the firm of Thos. Agnew & Sons for £600 on June 26[13]—the highest price paid for any of Holland’s watercolors, excepting the Turners—and on the same day, it was sold to Percy Holland, the son of Stephen George Holland.[14] The Holland family retained Lewis’s painting until 1937, at which time it was purchased by the dealer Rayner MacConnal for the drastically reduced sum of £110. 5 s.[15]

The name Rayner MacConnal also appears on a label on the verso of the oil version of The Reception. It reads: "From: Rayner MacConnal/Fine Art Dealer & Oriental Importer/(Wholesale & Retail)/Standbrook House/3, Old Bond Street, London." To the left, on the same label, are the words: "Also at/Grosvenor Galleries/Harrogate."[16] Though this information suggests that both the watercolor and oil versions of Lewis’s painting were in MacConnal’s possession at some point during their histories, MacConnal is not listed in the well-documented provenance of the oil.[17] It is possible that MacConnal, like several contemporary dealers, including Thos. Agnew & Sons, did not merely buy and sell works of art, but also organized and held exhibitions of modern British paintings, and that he borrowed the oil at a time when the watercolor was in his possession, in order to display them side by side. (His label would presumably have been affixed at this time.)[18] If true, this would be the only instance—historical or present-day—of the painting and the watercolor being seen together.

The next appearance of the watercolor version of The Reception is nearly twenty-five years later, on March 11, 1960, when it was sold at Christie’s London (lot no. 87), as part of the "Property of a Gentleman." It was bought by Frost & Reed Gallery, 2-4 King Street, St. James’s, London.[19] A year and a half later, in October 1961, Lewis’s picture was purchased by an American family, with whom it remains today. The transaction was a rather impulsive one, as the present owner recalls:

In October of 1961 I accompanied my parents by car from Northern Scotland to London. . . . The plan was to enjoy a few days visiting museums and galleries, but expressly to view a painting, a street scene by Tissot, that my father had decided to buy from Frost & Reed. . . . Very soon, my father . . . was given the news the painting for which he had made a deposit, some weeks before, had been sold. . . . [Instead] my father was asked to view another similarly detailed painting which they believed he might like. The Lewis watercolor was brought into the room, from wherever it was stored, for our perusal. All three of us gasped! My father was smitten instantly, but after a careful study of the masterpiece, he smiled and asked me, "Should I buy it?" to which I replied, "Yes, if you can!"[20]

Half a century after this serendipitous purchase was made, in the summer of 2007, I received a phone call from a man asking if I knew of a painting by Lewis he called Introduction to the Harem. A photograph sent to me by the caller in the following days revealed it was the watercolor version of The Reception, a work that had not been seen publically since 1961, and that was remembered only by a handful of textual references in contemporary periodicals, nineteenth- and twentieth-century auction and exhibition catalogues, and a long-out-of-print monograph penned by the artist’s great-grandnephew in 1978.[21] (No visual reproduction of the work had ever been publically circulated.) The man, the husband of the present owner, invited me to view the work in person as soon as I was able.

The unforeseen opportunity that came in 2007 to see the watercolor, and to subsequently compare the compositions of the two versions of The Reception, was enormously exciting. In addition to filling in a large visual gap in Lewis’s Orientalist oeuvre, the details of the watercolor against the oil have yielded important new information about the artist’s professional objectives, and his working methods. While the right-hand sides of the pictures are fairly similar, the left-hand sides display intriguing differences. The oil has fewer figures here, and includes only a portion of the set table.[22] (The part of the table that is shown, moreover, has different fruit on it; in the watercolor, fresh figs replace a cluster of grapes.) The absence or cutting off of these vignettes in the oil version might seem of little note—until one notices the lengths to which Lewis went in order to fill in the composition in the watercolor.

Along the left edge of the watercolor is a line that runs from top to bottom, marking where two sheets of paper have been joined (fig. 3). This suggests that The Reception, like many of Lewis’s watercolors, was extended at some point during the painting process, in order to accommodate an altered plan.[23] There are other differences between the two works as well: in the oil, the face of the woman reclining on the blue divan is shown in profile, whereas in the watercolor she offers a more engaging three-quarters view. In the watercolor picture too, her lips are parted, as if she is participating in the conversation with her attendant, rather than simply listening to her words. In general, in the watercolor, faces and hands are more thoughtfully executed, and express a more discernible emotion or attitude. The kneeling girl on the right-hand side of the composition, kept company by the gazelle, has far more delicate features than her counterpart in oil,[24] and the hand of the bowing female attendant opposite her is turned more gracefully and unambiguously toward the sky.[25] Each of her fingers is articulated with the thinnest thread of paint, and the rose-white flesh of her upturned wrist is almost palpably soft; in the oil, the hand is not nearly so well resolved.

The level of detail contained in the watercolor version of The Reception, and its expanded, larger size, may be explained in part by Lewis’s notorious dissatisfaction with the economic potential of watercolor (a thoroughly "unremunerative" medium, as he so memorably put it) and his continual attempts to overcome this financial problem.[26] In the years prior to this painting’s completion, and even after his abrupt resignation from the Presidency of the Old Watercolour Society in 1858, [27] the artist had taken great pains to perfect an idiosyncratic and calculated watercolor technique, one that could rival oil painting in the intensity of its hues, the precision of its brushstrokes, and—most importantly—in the prices it could fetch. [28] By offering to the public works that appeared as "finished" as an oil, and whose formidable size demanded both attention and respect, Lewis could persuade potential patrons that a watercolor was far more than an informal study or a preliminary sketch. [29] Indeed, by the early 1860s, Lewis had begun to systematically produce two nearly identical versions of a work, one in oil, destined for the Royal Academy, and one in watercolor. The watercolor was typically painted after the exhibition of the oil.[30] Presumably, this was to allow private collectors, both in London and, as in the case of Abel Buckley, outside of the city, to identify a favorite subject and commission a second version from the artist.[31] If these potential buyers were hoping for a substantially less expensive work, however, they would have been sorely disappointed: Lewis regularly negotiated the prices of his watercolors upward, based on their strategic similarities to the oils.[32]

The watercolor version of The Reception demonstrates Lewis’s astute commercial practice, first in the addition of the strip of the paper on the left hand side, and next in the picturesque details added to the (already visually abundant) composition. All of Lewis’s watercolor paintings created in 1873, in fact, were substantially larger and more detailed than their oil counterparts—a reflection, perhaps, of what had become a particularly critical moment in Lewis’s career.[33] Several letters from the period contain references to Lewis’s failing health, and the difficulty he was having producing works as efficiently as before.[34] The need to garner as much money as possible for his limited output, therefore, would have taken on a new importance—and the watercolor version of The Reception, a new poignancy as well.

The rediscovery of Lewis’s watercolor, and the opportunity for comparison that it provides, has allowed for a more complete understanding of Lewis and his art. It has, moreover, inspired a new set of questions regarding Lewis’s technical process, from the papers and brushes he chose to the particular pigments he used to achieve his opaque and jewel-like tones.[35] By appreciating the subtle differences between the two works discussed in this article, an alternative and thought-provoking lens has been provided through which to view Lewis’s efforts to perfect his craft, first with oil and then with water.

Emily M. Weeks

emweeks.art[at]gmail.com.

[1] The picture may have been brought to Buckley’s attention by Thos. Agnew & Sons or William Vokins (1815–95), both dealers who had established themselves in Buckley’s hometown of Manchester some years earlier. For a detailed history of Thos. Agnew & Sons, see Geoffrey Agnew, Agnew’s 1817–1967 (London: B. Agnew Press, 1967); and for a brief biography of the Vokins family, see Jacob Simon’s Selective Directory of British Picture Framemakers 1610–1950, 3rd ed., 2012, National Portrait Gallery, accessed August 3, 2013, http://www.npg.org.uk/research/conservation/directory-of-british-framemakers/v.php. For more on contemporary collecting practices in Victorian Manchester, see Elizabeth Conran, "Art Collections," in Art and Architecture in Victorian Manchester: Ten Illustrations of Patronage and Practice, ed. John H. G. Archer (Manchester and Dover, NH: Manchester University Press, 1985), 65–80.

[2] A dedicated and charitable Congregationalist and justice of the peace, as well as a well-known cotton-mill owner and businessman, Buckley had inherited the family home in Audenshaw in 1885. This was the same year that he was elected Liberal member of Parliament of the newly created Prestwich constituency.

On May 27, 1910, Christie’s held a sale of many of the pictures and drawings once owned by Buckley. Notable works included drawings by Richard Parkes Bonington, Henriette Brown, Jean-Léon Gérôme, David Cox, William Henry Hunt, and William Wyld, and oils by Thomas Faed, Frederick Goodall, Hubert von Herkomer, James Holland, Benjamin William Leader, John Linnell, William James Müller, John Phillip, and artists of the Continental School. In addition to the watercolor by Lewis, it appears that Buckley owned a handful of other Orientalist pictures, including a few by David Roberts. Pictures and Drawings—Abel Buckley, Mrs. John Fielden, T. H. Ismay, William Linnell, Sir W. Q. Orchardson, London: Christie, Manson & Woods, May 27 and 30, 1910. On January 24, 1924, additional works owned by Buckley were sold at auction. Many of these were important landscape and genre scenes by artists such as John Constable and Henri Fantin-Latour. Pictures & Drawings—Abel Buckley, London: Christie, Manson & Woods, January 24, 1924. Buckley is known to have owned works by Turner as well. This assortment was in contrast to most early nineteenth-century collections, which had tended to focus almost exclusively on Old Masters.

[3] The title of this picture changed dramatically—and meaningfully—over time, as I have documented in Emily M. Weeks, Cultures Crossed: John Frederick Lewis (1804–1876) and the Art of Orientalist Painting (New Haven and London: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, forthcoming), chap. 5 passim. For simplicity’s sake, I will refer in this article to both the watercolor and the oil as The Reception. The revolutionary politics of Lewis’s picture cannot be rehearsed here; they are discussed at length in chapter 5 of Weeks, Cultures Crossed.

[4] Buckley’s picture, known at this time as A Reception in the Hareem, was one of several works by Lewis collected by Thos. Agnew & Sons and displayed at the Jubilee, as a label on the verso of the painting and the checklist in the 1887 exhibition catalogue attest. See no. 1585, in Critical Notices of the Pictures and Water Colour Drawings in the Royal Jubilee Exhibition, Manchester, 1887, exh. cat. (Manchester: J. Heywood, 1887), 57. For more on Agnew’s unusual role as a mediator between collectors and exhibition venues, see Agnew, Agnew’s 1817–1967, 14. I would also like to thank Venetia Harlow, Archivist at Agnew’s, for information regarding this aspect of the firm. Email correspondence, Fall 2009. While at the Jubilee, The Reception was described by J. E. Hodgson, R.A., in his Fifty Years of British Art as Illustrated by the Pictures and Drawings in the Manchester Royal Jubilee Exhibition (Manchester: J. Heywood, 1887), 27: "In a picture of a ’Harem,’ which is in a well-known collection in London, he has represented a number of figures draped in garments covered with intricate patterns; over the whole he has thrown the shadow of the fretwork lattice which in Cairene windows replaces glass. It is a perfectly bewildering example of untiring patience." This is the only account from 1887 in which Lewis’s watercolor is mentioned specifically. The description of it being in a "well-known collection in London," rather than in Buckley’s possession, may indicate that a transference of ownership took place during or immediately after the Jubilee. (The exhibition label and catalogue both list the picture’s owner as Buckley, confirming that it was he who originally lent it.)

[5] Not all collectors of Lewis’s works were so generous: Joseph Arden (1799–1879), owner of Lewis’s famous Hhareem (ca. 1849, Nippon Life Insurance Company, Osaka, Japan), had vehemently refused to let the picture leave his house, for either the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855 or for the purposes of engraving. Memo written by Joseph John Jenkins, March 13, 1855, Jenkins Papers, Royal Watercolour Society Archives, Bankside Gallery, London. The "Jenkins Papers" is a collection of letters and papers relating to the history of the Royal Watercolour Society, and 106 individual artist files (including obituaries, letters, memoranda, catalogues, printed papers, cuttings, notes, etc.), brought together by Joseph John Jenkins (1811–85), the Secretary of the Society between 1854 and 1864. I would like to thank Simon Fenwick, Archivist of the Royal Watercolour Society, for providing me with a photocopy of this particular memo.

[6] For a brief mention of Lewis’s picture (no. 186) in the Third Room of the Exhibition, see What to see, and where to see it! or the Operative’s Guide to the Art Treasures Exhibition Manchester: Manchester Royal Institution, 1878), 12. Lewis had been heavily involved in the 1857 Art Treasures Exhibition, as well, in his capacity as president of London’s Old Watercolour Society. For references to this in letters to and from Lewis, see J57/23-24, J57/30, and J57/37, Jenkins Papers, Royal Watercolour Society Archives, Bankside Gallery, London.

[7] This may have been the first recorded appearance of the picture as "The Reception," as the exhibition catalogue and a label on the verso of the picture attest. See no. 142 in Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters and by Deceased Artists of the British School . . ., Winter Exhibition, 1891, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy, 1891). Perhaps not coincidentally, this was the same year that the oil, also now referred to as The Reception, was sold in London. The occasional overlap between the titles of Lewis’s oil and watercolor paintings, and the possible financial motivations behind this, are discussed in Weeks, Cultures Crossed, chap. 1 passim.

[8]Exhibition of Works by Members of the Club Together with a Selection of Works by the late J. D. Harding and the late J. F. Lewis, February 8–11, 1898, Royal Watercolour Society Art Club. Lewis’s picture appears as no. 44. Founded in 1884, the Art Club provided an opportunity for members of the Royal Watercolour Society to exhibit in an annual series of "Conversazioni." James Duffield Harding (1798–1863) was an established watercolorist and the drawing master of John Ruskin.

[9] In 1836, Holland and Frederick Sherry began their business at 10 Old Bond Street, London, specializing in woolens and silk cloths. (Holland & Sherry, as the firm was known, was particularly noted for its manufacture of crepe, a silk fabric used during the period for mourning.) In 1886, they moved their premises to Golden Square, then the center of the woolen trade. By 1900, the firm was exporting to many countries and a sales office was established in New York. Today, the business’s head office is located at 9/10 Savile Row. I would like to thank Mr. Anthony Holland and Mr. Andrew Aylwin for generously providing me with information about Stephen George and the Holland family. Email correspondence, September 17 and 25, 2009.

[10] Indeed, the total realized for the posthumous sale of Holland’s collection in 1908 was £138,118. 1 s.—the second highest amount ever realized for a collection of "modern pictures" in England to that point. "In the Sale Room," The Connoisseur, July 1908, 277. For a comprehensive list of the paintings and watercolors sold upon Holland’s death, see Catalogue of the Highly Important Collection of Modern Pictures and Water Colour Drawings of the English and Continental Schools of Stephen G. Holland, Esq., deceased, late of 56 Porchester Terrace, W., London: Christie, Manson & Woods, June 25, 26, and 29, 1908.

[11] Holland also owned a handful of Orientalist watercolors by noted European artists such as Henriette Browne, Ludwig Deutsch, and Carl Haag.

[12] Lewis’s picture was listed in the sales catalogue as "No. 230, A Lady Receiving Visitors in the Mandarah of a House in Cairo."

[13] Though most accounts agree with this figure, Graves lists the purchase price of Lewis’s picture as £630. Algernon Graves, Art Sales from Early in the Eighteenth Century to Early in the Twentieth . . . (London: A. Graves, 1921), 2:159. Agnew’s, it should be mentioned, only began to buy regularly from Christie’s in the 1850s, when Agnew’s also initiated the practice of purchasing works at the Royal Academy and the Old Watercolour Society, and from artists’ studios. For more on the firm’s purchase of artworks directly from artists’ studios, see Agnew, Agnew’s 1817–1967, 14–15.

[14] Stephen George Holland had nine children. Agnew’s involvement in this convoluted deal might have been predicted: The firm had already made a name in Manchester and London as an educated dealer and proponent of modern British watercolors (see note 1, above), and had consequently worked closely with Abel Buckley, Stephen Holland, and other admirers of Lewis’s art. It is conceivable, therefore, that Percy Holland would have approached this trusted family friend to aid him in a "commissioned purchase" of The Reception. My thanks to Venetia Harlow, Archivist, Agnew’s Gallery, for clarifying the details of this sale, and for suggesting this hypothesis. Email correspondence, fall 2009.

[15]Catalogue of modern pictures of the Continental schools, the property of the late Sir R. Leicester Harmsworth . . . water colour drawings the property of Percy Holland, Esq., deceased, late of 46 Hornton Court, W. 14 . . . , London: Christie, Manson & Woods, June 25, 1937. The catalogue lists the work as "No. 26, A Lady Receiving Visitors in the Mandarah of a House in Cairo." The disappointing sales price—which may have been a result of the lingering effects of a wartime economy—is confirmed in Art Prices Current, n.s (London: William Dawson & Sons, Ltd., 1936-1937), 16:A171, entry no. 5749.

[16] I would like to thank Cassandra Albinson, Associate Curator of Paintings and Sculpture at the Yale Center for British Art, as well as the center’s conservation department, for providing me with images and transcriptions of this label. Email correspondence, fall 2009. Though the details of MacConnal’s biography remain elusive, it is known that he owned several watercolors by Turner, many of them purchased at Christie’s in 1938 (see Ancient and Modern Pictures and Drawings of the Late Thomas Brocklebank. . . . London: Christie, Manson & Woods, July 8, 1938. Some of these pictures reappeared at the Sotheby’s sale of Mrs. Francis Tompkins (October 13, 1954), after having been in an "anonymous British collection." Eighteenth-Century and Modern Paintings and Drawings and Modern Sculpture, Sotheby’s London, 1954. Though the sale catalogue reveals that Tompkins owned one Lewis, Interior with Two Women Seated Before a Chinese Vase (lot no. 105), the watercolor version of The Reception does not appear in this sale, and its whereabouts between 1937 and 1960 remain unknown. I would like to thank Marcus Halliwell, director of MacConnal-Mason Gallery, 14 & 17 Duke Street, St. James’s, London, for information regarding the early history of the gallery, and Seth W. Armitage, Assistant Vice President, Specialist, Nineteenth-Century European Paintings, Drawings & Sculpture, Sotheby’s New York, for his assistance in locating the above-mentioned sales catalogue. Email correspondence, fall 2009 and May 29, 2013, respectively.

[17] Several of the previous owners of the oil version of The Reception were renowned collectors, with more than one Lewis to their name. The provenance of the oil painting is as follows: Bt. from the artist by Charles P. Matthews; Christie’s, C. P. Matthews sale, June 6, 1891, lot no. 76; Vokins; Christie’s, E. M. Denny sale, May 8, 1925, lot no. 143; V. Ely; Sotheby’s, George Farrow sale, March 15, 1967, lot no. 167, bt. P. & D. Colnaghi, from whom bt. [by Paul Mellon], 1967, lot no. 167. My thanks to Cassandra Albinson Associate Curator of Paintings and Sculpture, Yale Center for British Art, for her help in determining the provenance of this picture. Email correspondence, fall 2009.

Shortly before this article’s publication, it was brought to my attention that though MacConnal’s name is absent from the published provenance of this painting, he did purchase an "Oriental Scene" by Lewis with the same dimensions and date as the oil version of The Reception, at the Sotheby’s London sale of December 15, 1937 (lot 1121). MacConnal paid £120 for this work. I will be pursuing this tantalizing reference in the coming months. I would like to thank Lori Misura, Library Services Assistant the Yale Center for British Art, for this information. Email correspondence, August 5, 2013.

[18] See note 4 above. The words "No. 13 A Lady Receiving Visitors" are written in black script on the verso of the watercolor, along the wooden stretcher. This number cannot be correlated with the known exhibition or sales history of the picture. Could "No. 13," then, be a reference to its number in MacConnal’s undocumented show?

[19] I would like to thank Mr. Charles Kingzett, Director of Frost & Reed, for information concerning the arrival of Lewis’s work at their gallery. Email correspondence, fall 2009.

[20] Written account, provided to the author by the present owner, July 11, 2008.

[21] Michael Lewis, John Frederick Lewis, R.A. (1805–1876) (Leigh-on-Sea, England: F. Lewis, 1978), 97–98, no. 612. In keeping with the wishes of the owners, the reference to the watercolor in Mr. Lewis’s book was deliberately vague, and there was no accompanying picture. The recent obscurity of the watercolor and celebrity of the oil are somewhat ironic, for, prior to the mid-twentieth century, the situation was reversed: whereas the oil version of The Reception was exhibited only once before its arrival at the Yale Center for British Art (this being at the Royal Academy in 1874), the watercolor was exhibited several times (though only after Lewis’s lifetime).

[22] Also excluded from the oil composition is the lower edge of the pool of water, so that fewer reflections are visible. Such fragmented views might suggest that the wooden panel on which the oil version was painted has been cut down; however, this is not the case. I would like to thank Theresa Fairbanks and Mark Aronson, Conservators at the Yale Center for British Art, for their insights relating to the oil version of The Reception. Meeting at the Yale Center for British Art, Fall 2008.

[23] Though the present owners have repeatedly stated to me in conversation that they believe this line indicates a fold or crease in the paper, due to the picture having been reset in the frame, I believe it is indicative of a physical extension of the paper. The line is similar to those seen on other "extended" watercolors by Lewis, such as Courtyard of the Painter’s House, Cairo (ca. 1850–51, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery), comprised of five joined sheets of paper, and A Frank Encampment in the Desert of Mount Sinai, 1842—The Convent of St. Catherine in the Distance (1856; Yale Center for British Art), painted on three overlaid papers wrapped around a wooden board. I would like to thank Theresa Fairbanks for explaining Lewis’s construction of the latter picture to me, and for confirming my belief regarding the watercolor version of The Reception. Meeting at the Yale Center for British Art, fall 2008. The paper on which the watercolor version of The Reception was painted was once pinned to board; pinholes are visible along the left and bottom edges. Sometime during its early history, then, and like A Frank Encampment, it was laid permanently onto board.

[24] Michael Lewis was compelled to call the woman’s countenance "bewitching." Letter from Michael Lewis to present owners of the work, July 25, 1976, Private Collection.

[25] Mary Roberts has observed that the hand gesture of this woman was a well-known sign of either farewell or greeting, described in numerous British women’s travel accounts. Mary Roberts, "Travel, Transgression and the Colonial Harem: The Paintings of J. F. Lewis and the Diaries of British Women Travellers" (PhD diss., University of Melbourne, 1995), 102. For a thorough reading of each of the compositional details of the oil version of The Reception, as well as a historical and theoretical consideration of its subject matter, see chapter 5 in Weeks, Cultures Crossed; Emily M. Weeks, "Cultures Crossed: John Frederick Lewis and the Art of Orientalist Painting," in The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting, ed. Nicholas Tromans, exh. cat. (London: Tate Britain Publications, 2008), 22–32; and Emily M. Weeks, "A Veil of Truth and the Details of Empire: John Frederick Lewis’s The Reception of 1873," in Art and the British Empire, ed. Tim Barringer, Geoff Quilley, and Douglas Fordham (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2007), 237–53.

[26] Writing to his colleague Griffith in 1858, Lewis had explained his frustrations with watercolor in the most precise of terms: "Generally in spite of all my hard work, I find water colour to be thoroly [sic] unremunerative that I can stand it no longer—it is all, all always, rolling the stone up the hill—no rest, and such little pay!" John Frederick Lewis to T. Griffith, February 3, 1858, Private Collection, Surrey, England. See also John Frederick Lewis to Joseph John Jenkins, February 5, 1858, J57.54, Jenkins Papers, Royal Watercolour Society Archives, Bankside Gallery, London; and Lewis’s earlier letter to Jenkins, J57.50, Jenkins Papers, Royal Watercolour Society Archives, Bankside Gallery, London. Lewis’s dissatisfaction with watercolor is also noted briefly in "John Frederick Lewis, R.A.," The Portfolio 23 (1892): 95. For two particularly eloquent summaries of the economic challenges faced by watercolorists in the nineteenth century, see Simon Fenwick and Greg Smith, The Business of Watercolour: A Guide to the Archives of the Royal Watercolour Society (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1997); and Greg Smith, "An Art Suited to the ’English Middle Classes’?: The Watercolour Societies in the Victorian Period," in Governing Cultures: Art Institutions in Victorian London, ed. Paul Barlow and Colin Trodd (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), 114–27. Another scenario, though admittedly more imaginative, may also be worth exploring. If The Reception was begun in Egypt, as some of Lewis’s larger and more complex watercolors were, then it may have been a shortage of paper that accounted for the picture’s modification. By the mid-nineteenth century, an artist in England would have had any number of machine-made papers to choose from, in a variety of lengths, if not widths. In Cairo, however, where Lewis lived for nearly a decade, the selection would have been far more limited, being dependent upon either the artist’s current stash or his supplier’s efficiency and skill. (Lewis’s dependence on the arrival of supplies from England was recorded at least once during his tenure abroad: in March 1841, the Art-Union reported that the artist had "recently ordered a supply of drawing materials from England," and was therefore likely to remain in Constantinople for some time. Art-Union 3 [March 1841]: 49.)

[27] For an intriguing, first-hand account of Lewis’s tumultuous relationship with the Old Watercolour Society, see the series of letters between and about Lewis and his colleagues: J57/50-74, Jenkins Papers, Royal Watercolour Society Archives, Bankside Gallery, London. See also Simon Fenwick, The Enchanted River: Two Hundred Years of the Royal Watercolour Society (Bristol: Sansom, 2004), 57–59, 61, 63–64; and for more on Lewis’s struggle to reconcile his facility and enthusiasm for watercolor with its economic returns, see Weeks, Cultures Crossed, chap. 1 passim. For a unique interpretation of Lewis’s shift between artistic mediums, which makes use of the writings of Freud and Lacan, see Nicholas Mirzoeff, Bodyscape: Art, Modernity and the Ideal Figure (London and New York: Routledge, 1995), 114. Though the Old Watercolour Society did not permit its members to exhibit in oils, it is interesting to note in the context of The Reception that it had for some time paid out a sizable proportion of its profits in premiums to encourage members to produce larger and more complex pieces that more closely resembled oil paintings, which they then exhibited in gold frames. Smith, "An Art Suited to the ’English Middle Classes’?," 121. For Lewis’s own reference to this practice, see John Frederick Lewis to John Noble, January 24, 1855, fol. 232-3, MS Autog c 17, Percy Noble Collection, Bodleian Library, Oxford University. It should be noted as well that there was a period between 1813 and 1820 when the Society was temporarily reconstituted as the "Society of Painters in Oils and Watercolours" (emphasis mine).

[28] Whereas a modestly sized oil painting might easily fetch an impressive amount of money at auction, or from an openhanded patron, a comparably sized watercolor would not. An artist working in watercolor would therefore have to work especially hard to provide potential buyers with evidence of the value they were getting for their money. Most often, this "evidence" took an obvious and physical form—the larger and more meticulously detailed a work, the more merit it was seen to have. For more on Lewis’s early career as a watercolorist, see Kenneth Bendiner, “Lewis, John Frederick (1804–1876),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed August 3, 2013, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16592; and Lewis, John Frederick Lewis, R.A., 11–20. This period of Lewis’s life was also made the focus of an exhibition at London’s Royal Academy of Arts in 2008. See Briony Llewellyn and Sally Doust, The Young Lion: Early Drawings by John Frederick Lewis, R.A. (1804–1876): A Guide to the Display (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2008).

[29] Lewis went so far as to refuse to send his watercolors to the Old Watercolour Society’s exhibitions unframed, so fearful was he of their being mounted in white and "reduced to the level of sketches." For the full quote, and some helpful context, see Lewis’s letter to Joseph John Jenkins, July 8, 1857, J57/37, Jenkins Papers, Royal Watercolour Society Archives, Bankside Gallery, London.

[30] So habitual was this practice that it is possible to say that if Lewis exhibited an oil painting at the Royal Academy during his mature career, then there was almost certainly a later watercolor version of the work. This practice began, although sporadically, as early as 1856, when two versions of A Syrian Sheikh, Egypt were produced and subsequently exhibited. It is interesting to note that in some rare instances, two watercolor versions of a picture exist, with no related oil; e.g., The Hhareem. The "complete" version of this picture is with the Nippon Life Insurance Company in Osaka, Japan, while a second, abbreviated rendition, once owned by Miles Birket Foster, is now part of the Prints & Drawings Collection at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London.

Two exceptions to this chronological rule are: A Frank Encampment in the Desert of Mount Sinai, 1842—the Convent of Saint Catherine in the Distance. The picture comprises Portraits of an English nobleman and his Suite, Mahmoud, the Dragoman, Etc., Etc., Etc., Hussein, Scheikh of Gebel Tor, Etc., Etc. (the watercolor was painted in 1856 and the oil in 1862) and The Bezestein Bazaar of El Khan Khalil, Cairo (an oil painted in 1874 is nearly identical to a watercolor in the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, entitled The Bazaars, Cairo and dated 1872). In a third work, one of a series entitled The Street and Mosque of the Ghooriyah, Lewis employs both oil and watercolor, making a timeline for their use impossible. One final qualification must be noted as well: the pencil and watercolor versions of Indoor Gossip and Outdoor Gossip are unequivocally described by Michael Lewis as "preliminary sketches" for the smaller oils. Lewis, John Frederick Lewis, R.A., 98, cat. nos. 614 and 616.

[31] Lewis’s dealers, it should be mentioned, could also benefit from this practice, having a "catalogue" of options to show their clients. For a discussion of contemporaries’ eventual dissatisfaction with Lewis’s recycled compositions, see Weeks, Cultures Crossed, chaps. 3 and 6 passim. See also John Frederick Lewis to David Roberts, April 8, 1862, Bicknell Album of Artist Letters, Department of Rare Books and Archives, Yale Center of British Art, New Haven.

[32] For a summary of the elaborate negotiations that sometimes went on between Lewis and his patrons and dealers, see Emily M. Weeks, "’For Love or for Money’: Collecting the Orientalist Pictures of John Frederick Lewis (1805–1876)," Fine Art Connoisseur 4, no. 1 (January-February 2007): 40–47. It is worth noting that Lewis did not limit this clever ploy to watercolors alone: in a series of letters between the artist and the British collector John Noble, written between 1854 and 1855, Lewis’s canny maneuvering is apparent as the two try to determine the price of an oil painting Noble has just commissioned. John Frederick Lewis to John Noble, January 24, 1855, fol. 232-3, MS Autog c 17, Percy Noble Collection, Bodleian Library, Oxford University.

[33] The pictures to which I refer are: Indoor Gossip (oil, 12 x 8 inches; pencil and watercolor, 20 ½ x 15 1/8), Outdoor Gossip (oil, 12 x 8 inches; pencil and watercolor, 21 15/16 x 15 3/8 inches), and The Reception (oil, 25 x 30 inches; watercolor, 29 x 41 inches). For more on the oil versions of these paintings, see Weeks, Cultures Crossed, chap. 5 passim.

[34] In a letter to Thomas Woolner (1825–1892) dated May 4, 1874, Lewis indicated the gravity of his situation: "Ill as I am—hardly able to hold the pen—" he began. Quoted in Amy Woolner, ed., Thomas Woolner, R.A.: His Life in Letters (London: Chapman and Hall, 1917), 293–94. On the 17th of that month, Woolner laments: "After such a long habit of close work to be denied it is indeed a loss." In November, Lewis relates that he is now almost deprived of locomotion (ibid., 299) and, on January 28, 1875, that he had been incapable of writing, due to his poor health (ibid., 302). By March 1876, Lewis was confined to a wheel chair. Though he had long suffered from painful arthritis and other ailments, the rapidity with which Lewis declined after 1873 may suggest that he was the victim of a stroke.

[35] I explore these questions in great detail in Emily M. Weeks, "The Tools of His Trade: The Relationship Between John Frederick Lewis (1804–1876) and Charles Roberson & Co.," Hamilton Kerr Institute Bulletin, forthcoming.