The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

February 17–May 19, 2013

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848–1900, a joint effort by the National Gallery of Art (Washington, DC) and Tate Britain (London), is the first major exhibition of English Pre-Raphaelite art ever to grace American shores (fig. 1). Until now, we former colonists have not had an opportunity to view these stunning works en masse. What took so long? Judging by the flurry of reviews that followed in the wake of this remarkable show, it is clear that the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) are as controversial and divisive today as they were a century-and-a-half ago. Were they reactionary or retrograde? Medieval or modern? Patrician or plebian? Prophets or perverts? Critiques span both sides of the Atlantic, and some are hardly complimentary. John Walsh’s clever, patronizing piece declares the PRB to be “backward looking and conservative,” and is as intrigued by the juicy details of the Brotherhood’s personal lives as by their artistic contributions.[1] Roberta Smith’s remarkably prejudiced and shallow review in The New York Times begins with the caveat, “You won’t see much in the way of great paintings,” and suggests that, if “sophisticated” viewers wish to see “great” art, there is plenty of it among the Cézannes and Manets in adjacent galleries.[2] Reading this, I imagined myself transported back in time several decades to my first art history survey class, periodically dozing and listening half-heartedly to what H. W. Janson had to say about the triumph of modernism in the early twentieth century.

I am a convert to nineteenth-century art; my early training was in the Northern Renaissance. So I have no problems with the flamboyant technique, obsessive realism, moral topoi, sweet sentiment, narrative content, and dense literary contextualizing of the Pre-Raphaelites. They were, after all, inspired by my first love, the so-called “primitives,” who received their own dose of unfavorable criticism in their time. None other than Michelangelo, impressed with his own macho Italian patrimony, declared early Flemish painting suitable for “women, especially the very old and very young.”[3] But that was five hundred years ago, and the discipline of art history has evolved since then. Most of us now accept that women of all ages are fully capable of comprehending the wonders of early Renaissance art. And “sophisticated” viewers no longer employ the same visual and interpretive criteria when looking at paintings by Cézanne and the Pre-Raphaelites. The PRB spoke for an era that was profoundly different from our own. Their works are the product of a unique common wisdom, belonging to a specific time and place. The National Gallery show and its excellent accompanying catalogue recognize this by putting the “history” back into art history.[4]

The members of the PRB were brash young men, like their contemporaries the romantics and Realists on the other side of the Channel. The leaders of the group began their great experiment as teenagers, still living with their parents. Precocious youths, they were educated at Oxford and classically trained at the Royal Academy of Arts. Their fine intellectual and technical pedigrees were the basis for their rebellion, which was a calculated assault on tradition. As painterly wunderkinds, the PRB were the artistic counterpart of the composer Felix Mendelssohn, who created the immortal Overture to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream when he was only seventeen. Grounded in religion, history, and literature, yet fairly bursting with sentiment, these towering cultural figures embodied a unique merging of raw talent and classical training, commanded by fearless youthful exuberance.

The results of the PRB’s quest are difficult to categorize within the canon set forth in the first edition of Janson’s History of Art.[5] They were Realists in their meticulous photographic representation of the natural world, but their subject matter was decidedly romantic, inspired by historical, religious, mythic, and literary sources. In technique and subject matter, the PRB sought to revive early Renaissance painting, both Italian and Northern, as it existed before Raphael’s measured elegance and Michelangelo’s extroverted exuberance. Though Pre-Raphaelite painters experimented with traditional wood panel supports, they were not averse to employing new chemical pigments invented during the industrial revolution. The National Gallery exhibition vibrated with the intensity of the PRB’s signature high-pitched purples and cobalt blues, intensified by a zinc white ground and bounded by hard-edged contours (fig. 2). Both medieval and modern, the Brotherhood echoed the formative days of the discipline of art history, when the “primitives” were discovered anew, and Hans Memling became one of Queen Victoria’s favorite artists.

In the National Gallery, viewers could experience the full impact of the freshness and refinement of these paintings at close range, undeterred by the irritating glare of protective glass and laser security beams. Brief wall texts and descriptive labels provided basic concepts and limited historical background. For a fuller understanding, viewers were encouraged to consult the exemplary catalogue, which leaves no stone unturned in its eleven meticulously researched and articulate essays and 175 individual entries (fig. 3). The placement of works in eight densely hung galleries in Washington, DC paralleled the organization of the catalogue, with the exception of the conflation of the catalogue’s “Origins” and “Manifesto” divisions into a single room, and the addition of a section devoted to “Literature” in the National Gallery venue.

The public was welcomed into the exhibition by a wall-text, which introduced the PRB as Britain’s first avant-garde movement. Works devoted to the Bible, Boccaccio, Chaucer, and Shakespeare dominated the first room, dedicated to “Origins.” Two photographic reproductions of paintings by Lorenzo Monaco and Jan van Eyck, relegated to an obscure corner, represented the PRB’s painterly antecedents. I could not help but wonder why, in a museum noted for its magnificent fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Renaissance paintings, small, inadequate photos sufficed for the real thing. How much more satisfying it would have been to see actual panels by Taddeo Gaddi and Rogier van der Weyden here, borrowed from the National Gallery’s permanent collection.

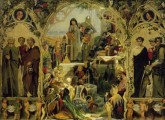

The “Origins” room displayed several well-chosen paintings by leaders of the movement, among them Ford Madox Brown’s The Seeds and Fruits of English Poetry (1845–53) (fig. 4), William Holman Hunt’s Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1850–51), and John Everett Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents (1849–50) (fig. 5). These represented the group’s thematic choices, which ranged from Biblical scenes to medieval history. The celebrity tenant of this space was Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents, which represented nineteenth-century critical responses to the PRB’s tendency to play fast and furious with the facts. Densely iconographic and sentimental in its evocation of an imagined event from Christ’s childhood, this painting still has the power to shock by its uncomfortable convergence of Biblical morality and prosaic reality. Millais’s divine characters possess ordinary, English faces, and display universal human emotions. The usual format for such a serious subject would have been to arrange the protagonists in a respectful theatrical tableau. Millais, however, painted the extended Holy Family engaged in a common, workaday environment. It was all too much for Charles Dickens, who decried the young Christ as a “hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-headed boy.”[6] The esteemed British author evidently could not envisage one of his own heroic street urchins as the youthful Savior. This controversial painting set important precedents for future works by the Brotherhood, which, in the eyes of proper Victorians, sometimes bordered on blasphemy.

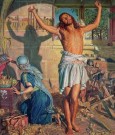

From “Origins,” viewers entered consecutive galleries devoted to the themes of “History,” “Literature,” “Salvation,” “Nature,” “Beauty,” “Paradise,” and “Mythologies” respectively. A thematic approach is a helpful way to make sense of the dense content of these paintings and the diverse frames of reference from which the PRB drew. However, the logic behind these specific thematic divisions was not immediately apparent. Many works seemed misplaced or loosely related to the categories, while others, such as paintings inspired by Shakespeare, were everywhere, showing up in the “Origins,” “History,” “Nature” and “Literature” categories. A separate room could have been devoted to the Bard alone. The theme of “Salvation” featured intensely pious subjects side-by-side with less than pristine moral exemplars. It was somehow unseemly that Hunt’s flamboyantly homoerotic The Shadow of Death (1870–73) (fig. 6) shared visual space with the easy women in Awakening Conscience (Hunt, 1853–54) and Found (Rossetti, ca. 1859) (fig. 7). It is true that the concept of moral salvation permeated every aspect of Victorian culture, but to me, these very dissimilar paintings did not complement each other.

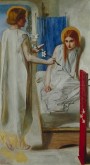

Granted, there are not always distinct separations among the themes and narratives of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, which are multivalent and complex in their subjects. And such divisions are necessarily defined by opinion. Yet, I could not help but wonder how Rossetti’s Biblical Ecce Ancilla Domini! (Annunciation, 1849–50) (fig. 8) and Hunt’s Lady of Shalott (ca. 1888–1905) (fig. 9), after a poem by Tennyson, ended up in the “Mythologies” gallery. The exhibition organizers attempted some clarification of the catalogue’s similarly capricious thematic divisions, devoting a separate room to “Literature.” Here, Millais’s famous Ophelia (1851–52) drew a crowd of captivated viewers (fig. 10). Reading the accompanying label, they learned, among other things, that Millais’s model and mistress Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall caught a cold posing for this picture in a bathtub.

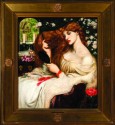

Apart from this brief foray into gossip, the show generally resisted delving into the risqué scandals that seemed always to surround the lives of these brilliant and beguiling young men and women. However, the room devoted to the theme of “Beauty,” paid frank tribute to the “sweet mystery of life” (fig. 11). Here were the women who zealously served as mistresses and muses of the PRB, resplendent in their abundant wavy hair, columnar necks, and pouting, Angelina Jolie lips (fig. 12). Photos of Jane Morris and Elizabeth Siddall graced one wall, proving how idealized the Brotherhood’s vision of the feminine actually was. Soft-focused photographic portraits of women by Julia Margaret Cameron were displayed side-by-side with sculpted female likenesses by Alexander Munro. Apart from her gender, Cameron held little in common with the wives and sweethearts who shared this gallery, as she was only casually (and chastely) linked with the Brotherhood.

Sadly, the superficial objectification of women under the general rubric of “beauty" in this room did not match the high scholarly standards of the rest of the exhibition. Obviously, women are omnipresent in the works of the PRB. But apart from idealized sexuality, they also embody the fierce debate about women’s roles and capabilities that gripped the industrialized world in the nineteenth century. The female friends, wives, and lovers of the PRB could not yet vote or attend university. But the men of the Brotherhood, like all men of their time, knew full well that women themselves protested forcibly and publicly against the patriarchal assumption that their most valued talents were passive beauty and sexual accessibility.

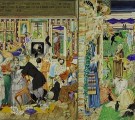

I could not help but view the “Beauty” gallery as a lost opportunity. How much more exciting and relevant it would have been to explore the concept of the femme fatale, a category that embodies the well-documented fear and distrust of women’s sexuality that arose in the wake of organized feminism. Rossetti’s Lady Lilith (1872–73), the mythical and malevolent first wife of Adam, is an appropriate example (fig. 12). However, in this room she was treated as just one of many blandly eroticized women. Even the many representations of female self-sacrifice and fidelity, which appeared throughout the exhibition, could have been contextualized within the renewed emphasis on marriage, home, and family that arose in nineteenth-century Britain. Furthermore, at least twenty serious female artists were associated with the PRB, enough to form a veritable “Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood.” In tribute to this reality, it would have been interesting to explore, for example, the contributions of May Morris, daughter of William and Jane Morris. A writer, social activist, and artisan, she eventually published her father’s works in twenty-four volumes. Paintings by Rosa Brett (fig. 13), Florence Claxton (fig. 18), and Elizabeth Siddall were, in fact, included in the show, though they were placed in other rooms. References to women in the “Beauty” group were more concerned with their passive function as bedmates than with their active roles as artists and creators.

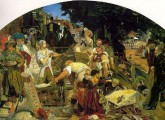

Though the organizing principles of the National Gallery show seemed at times unclear, there is no faulting the scope and quality of its offerings. This extraordinary gathering presented a veritable embarrassment of riches, including not only paintings, but also decorative arts, furniture, and printed books. In addition to the stars already mentioned, other favorites were on exhibit, among them Hunt’s iridescent The Light of the World (1851–52) (fig. 14) and Brown’s iconographically complex Work (1852–63) (fig. 15). Though works by the major figures Rossetti, Brown, Burne-Jones, Hunt, and Millais predominated, paintings by lesser-known artists also appeared. Among them were several radiant landscapes, in the “Nature” gallery, by John William Inchbold (At Bolton, 1855), and Daniel Alexander Williamson (Spring, Arnside Knot and Coniston Range of Hills from Warton Crag, ca. 1864) (fig. 16). Less familiar literary and moralistic subjects included intriguing compositions by John Roddam Spencer Stanhope (Thoughts of the Past, 1858–59) (fig. 17) and Florence Claxton (The Choice of Paris: An Idyll, 1860) (fig. 18). Rare stained-glass panels devoted to the quasi-literary-historical figure René of Anjou, King René’s Honeymoon, occupied a wall of the “Literature” gallery (fig. 19). A collaborative work by Rossetti, Burne-Jones, and Brown, these unique scenes, devoted to Music, Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, have never been seen outside of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Due to their fragility, they probably will never cross the Atlantic again.

Thanks to the efforts of the organizers of this exhibition, and despite the naiveté and jadedness of a few critics, we need no longer view the Pre-Raphaelite movement as the awkward step-child of modernism. The National Gallery’s show is, in truth, a magnificent achievement. A joyous expression of beauty and brilliance, it provides a window into a time when substance and technique were celebrated as integral parts of the artistic experience, and everybody could quote their favorite lines from Shakespeare and Tennyson.

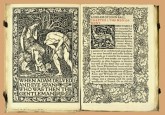

Also appearing in Washington were designs by Morris & Co., including wallpaper patterns, woven textiles, painted ceramic tiles, and books produced by the Kelmscott Press. These were placed together in the gallery devoted to “Paradise.” I was initially confused by this thematic designation, but was reassured when confronted by an exquisite illuminated English translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (1872), produced in gold, ink, and watercolor on vellum (fig. 20). Among several beautiful hand-printed books was one opened to a page from William Morris’s novel A Dream of John Ball (1888) (fig. 21). Accompanying an image of Adam and Eve toiling after the Fall, the text on this well-chosen page elucidated the social agenda of the PRB in one simple question: “When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?”

Walking through this exhibition, I was reminded at every turn of the far-reaching influence of the PRB, which extends to our own contemporary media culture. As an organized movement, the Brotherhood lasted only five years. However, their principles prevailed throughout the century, underlying the Aesthetic and Arts and Crafts movements. But what Game of Thrones (fig. 22) fan could fail to see connections to Morris’s La Belle Iseult (1857–58) (fig. 23) or Millais’s Isabelle (1848–49) (fig. 24)? The PRB continues to inspire, even in Hollywood. Word has it that a film devoted to the tangle of art and love among John Everett Millais, John Ruskin, and his wife Effie Gray is planned for release in the near future. Directed by Oscar-winning screenwriter and actress Emma Thompson, it will star Dakota Fanning as Effie.

The resources of the National Gallery’s exemplary education department supported this exhibition in creative and original ways. For scholars, there was a multi-part symposium, “Pre-Raphaelites and International Modernisms,” sponsored by the Department of Art History at Yale University, and featuring world-renowned experts. The general public could take advantage of an opening lecture by the exhibition’s curators, a digital brochure, gallery talks, concerts, and even a bookmaking workshop. The museum’s Garden Café, which never lacks for delicious offerings, supplemented its menu with British favorites. Where else could one get a Cornish pasty and a generous helping of bubble and squeak?

Laurinda S. Dixon

Syracuse University

lsdixon[at]syr.edu

[1] John Walsh, “A-Z of the Pre-Raphaelites: Rebel Painters of a Completely Different Nature,” The Independent (18 June, 2013).

[2] Roberta Smith, “Blazing a Trail for Hypnotic Hyper-Realism,” The New York Times (March 29, 2013).

[3] Quoted in James Snyder, Northern Renaissance Painting, second edition (Upper Saddle River, N.J,: Prentice Hall, 2005), 87.

[4] Tim Barringer, Jason Rosenfeld, and Alison Smith, Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design (London: Tate Publishing, 2012).

[5] H. W. Janson, History of Art (New York: Abrams, 1962).

[6] Quoted in Barringer, Rosenfeld, and Smith, Pre-Raphaelites, 116.