The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

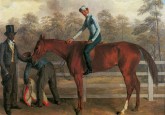

Between 1832 and 1870, Edward Troye (1808 – 1874), the leading animalier of nineteenth-century America, created a body of paintings that depict celebrated Thoroughbred racehorses with their African American jockeys and handlers.[1] In one of the artist’s finest group scenes, Tobacconist, with Botts’ Manuel and Botts’ Ben (fig. 1), painted for John Minor Botts (1802–69) at Half Sink Plantation in Henrico County, Virginia, Troye represents the slave jockey Ben holding a bay horse whose pinned ears and raised tail reveal his displeasure in being unsaddled by his trainer Manuel, also a slave. Troye composed the picture as he did so many: setting the animal against a backdrop of leafy foliage and framing him with nearly barren tree trunks. Taking in the painting, a viewer’s eyes rake naturally across the horse’s athletic form, from muscled rump to strong back to outstretched neck and head. Yet Troye arrests the eye’s arcing traverse with the faces of Ben and Manuel. Both gaze pensively outwards. Ben, in blue silks and red stockings—identifying the Botts stable colors—holds fast to Tobacconist’s reins.[2] Manuel, with powerful forearms peeking out from rolled up white shirtsleeves, turns to look over his right shoulder. During the antebellum period, black horsemen dominated the racing landscape. Most were slaves; some were free blacks. Granted high status, they frequently earned salaries and were able to cross state lines to race and transport horses. Throughout the South, the epicenter of racing until the Civil War, they worked at training stables, farms, and tracks: planning conditioning schedules, grooming horses, managing feed and veterinary programs, and riding. Accordingly, Troye’s pictures offer a unique opportunity to explore a space where social history, racial ideologies, and the conventions of portraiture converge.

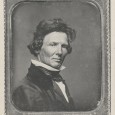

Troye painted nearly every distinguished horse in American flat and harness racing during his lifetime. His portraits adorned homes, stables, and even hotels, and were also disseminated widely as engravings. Born in 1808 in Lausanne, Switzerland to a French Protestant artist family, Troye spent his early life in England. He left at the age of twenty, going first to Jamaica to manage a sugar plantation.[3] Three years later, in 1831, he went to Philadelphia. After a short period working as an animal illustrator, a fortuitous commission from local breeder and racing aficionado John Charles Craig (1802–37) catapulted Troye into what would become his chief career as antebellum America’s leading animal painter. Throughout the 1830s, the artist traveled from farm to farm and racecourse to racecourse building his reputation. Following his marriage in 1839 to Kentuckian Cornelia Ann Van de Graaf (1812–89), he expanded his entrepreneurial talents, trying his hand at farming in Kentucky, first in Scott County and later near Paducah. Between 1840 and 1846, the couple had four children, three of whom died in infancy.[4] Late in 1847, Troye sold his farm and a prominent racing magazine declared that he was bound for Havana. If he went at all, by 1849 he was back in the United States teaching French and drawing at Spring Hill Academy in Mobile, Alabama. There, in addition to animal portraits, he crafted several conversation pieces featuring local residents.[5] In 1855 Troye left Mobile to travel to the Holy Land to import Arabian stock with one of his most significant patrons and close friends, Kentuckian Alexander Keene Richards (1827–81).[6] Several years before his death the artist and his family settled in Madison County, Alabama, but Troye continued to keep a studio in Kentucky at Blue Grass Park, Richards’s home, near Georgetown and many of his long-term patrons. He died at Blue Grass Park in 1874.[7]

The extensive literature on Troye has been assembled mainly by sports historians and sporting art collectors. Harry Worcester Smith (1865–1945), an avid equine sportsman and art collector, was one of the earliest to revitalize interest in Troye when he began collecting and researching the artist during the 1920s and ’30s. Traveling throughout the South, he documented Troye paintings and purchased them, along with letters and photographs, sometimes using questionable ethics.[8] Alexander Mackay-Smith’s Race Horses of America, 1832–1872: Portraits and Other Paintings by Edward Troye (1981) is the definitive study of the artist and a critical resource for racing enthusiasts and Troye scholars. Building on research by Worcester Smith and Kentucky historian J. Winston Coleman, Jr. (1958, 1974), Mackay-Smith (1904–98), another equine sports enthusiast-scholar and founder of the National Sporting Library in Middleburg, Virginia, exhaustively traces Troye’s career and meticulously identifies his subjects.[9] Genevieve Baird Lacer’s more recent, lavishly-illustrated book on Troye takes a slightly different approach to his oeuvre. Collecting together the engravings that were made after his paintings and published in the American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine, along with excerpts about the horses from this and other magazines, Lacer recounts the careers of the horses and offers a glimpse of the flavor of the nineteenth-century sporting press and how Troye’s engravings functioned within it.[10]

Taking these texts as starting points, this essay examines what I believe are some of Troye’s most provocative images: his group portraits featuring African American trainers, grooms, and jockeys. In these, Troye quite deliberately emulates the sporting pictures of his British predecessors, John Nost Sartorius (1759–1828), Benjamin Marshall (1768–1835), James Ward (1769–1859), John Fernley, Sr. (1781–1860), and especially George Stubbs (1724–1806), with all of whom he would have been intimately familiar growing up in England and from seeing their prints in his patrons’ homes and in sporting journals. Drawing on Dutch, Flemish, and French models, these artists helped popularize the outdoor conversation piece and developed iconographies of the hunt scene and racehorse portrait that included horses and owners, in addition to huntsmen, gamekeepers, and stableboys. Their images came to reflect contemporary English upper-class society: its Enlightenment views of nature and nature’s relationship to a moral and healthy body, its growing obsession with country sports and animal breeding, and the expansion of its country estates that necessitated greater, more specialized and stratified staff.[11] While black grooms occasionally appear as a colonialist impulse to lend a sense of the exotic, estate laborers in English paintings by artists like Stubbs are more frequently white, humble servants, whose names are often known through paintings’ titles, labels, and accompanying keys.[12] By including various attendants with his equines, Troye surely accommodated his American patrons’ wishes for the time-honored, elitist trappings of Old World sporting pictures and even cast himself as a cosmopolitan European animal painter for marketing purposes. But he adapted his scenes to suit his context and therefore featured the African American grooms, trainers, and jockeys who pervaded the American racing world. His depictions of these men resist and therefore complicate interpretations of what Alain Locke called the page format or plantation formula, meaning the convention of including black servants and slaves in portraits to heighten the exoticism of the scene or to mark the horse’s or owner’s identity and repute.[13] In doing so, Troye importantly documented specific individuals within a black American professional sporting subculture and their contributions to the history of American Thoroughbred racing.

Southern Horseracing in the Antebellum Period

The ambivalent nature of Troye’s group paintings—in that they are at once both derivative of their early modern models and intriguingly inventive in their candid, serious portrayals of African American professional riders and handlers—reflects the development of American racing in the first half of the nineteenth century. During this period, racing experienced enormous growth and regulation, shedding some and retaining other aspects of its genteel trappings. Interest in the sport ignited in 1823, the year of the famous Great North-South Match Race between the New Yorker American Eclipse and the North Carolinian Sir Henry on Long Island.[14] Following Eclipse’s win and the race’s immense popularity with fans, promoters rushed to stage sectional matches between horses who symbolized North and South, and East and West, to further capitalize on socio-political and geographic divisions deepening in the United States. Although Troye did not attend the Eclipse-Henry match, he did witness many of the next decades’ distinguished contests traveling as an itinerant painter throughout the country in pursuit of commissions. His clientele included the burgeoning sporting presses of the day as well as notable private patrons.[15] The front pages of the American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine (founded in 1829) and Spirit of the Times: A Chronicle of the Turf, Agriculture, Field Sports, Literature and the Stage (founded in 1831) regularly featured engravings after Troye’s paintings along with a narrative of the equine subject’s career. The editors remained faithful supporters of the artist, even when readers complained of the anatomical and expressive deficiencies of his animal representations.[16] While the engravings helped secure Troye’s name as the animal painter of his era and heightened the artistic and hence commercial value of the magazines, as likenesses of horses’ appearances they also formed important elements in a broader, multifaceted record-keeping initiative. This initiative, which sought to preserve the purity of bloodlines and construct a bona fide history of the American Thoroughbred, began in earnest during the antebellum period and included not only visual documents—the animal portraits—but also written pedigrees, race reports, stud and stock books, and jockey club minutes.[17]

That the major record-keeping entities for horseracing—the sporting presses, first official studbook, and [American] Jockey Club—originated in the northern United States[18] often supports sports historians’ claims that the story of modern American sports belongs to the North. Resulting from the Industrial Revolution’s transformation of patterns of labor and leisure, modern American sports; namely, harness racing, baseball, boxing, and track and field, may be characterized by their commercialism, professionalism, national competition, expanded spectatorship and press coverage, and institutionalized rules and regulations, which, scholars argue, spring necessarily from industrialized, urban centers.[19] Few prosperous cities existed in the largely agricultural South that had been further crippled by the effects of the Civil War. Therefore, because of this characterization of modern sport as a distinctly northern, urban phenomenon, southern antebellum (and even postwar) sport has traditionally been understood as an anti-modern activity: one in which its contests contained some rudiments of specialization, rationalization, and quantification, but its participants remained gamblers and amusement seekers above all else, rather than professional sportsmen.[20] In this interpretation, southern flat racing persisted as the “sport of kings,” an activity in which planters—and Troye’s patrons—as owners of vast lands and slaves, construed themselves as aristocrats, and, in the words of turf historian John B. Irving (1800–1881), were “the impersonation of Carolina chivalry—the embodied spirit of Carolina blood and Carolina honor.”[21] The sport’s tradition of sartorial splendor, specifically the top hats and tails worn by trainers in the English tradition, evidences its desire to perpetuate its noble lineage. And even in the North, flat racing retained many of these aristocratic associations in contrast to harness racing, which increasingly gained in both popular and populist appeal.

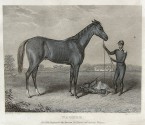

Historian Kenneth Cohen, however, has challenged such simplistic assumptions about southern racing, showing that in the mid-Atlantic states and in the South, particularly the Chesapeake region including the states of Virginia and the Carolinas where Troye frequently painted, it rapidly advanced on a path towards profit and professionalism. A new breed of turf men, those like one of Troye’s early patrons, William Ransom Johnson (1782–1849), better known as the “Napoleon of the Turf,” overtook wealthy planters as the leaders of the industry.[22] Indeed, many of Troye’s southern patrons and business associates proved integral in shaping the organizational structures, rules, and profit potentials of the national racing industry. Johnson became one of the best trainers and shrewdest businessmen on record, with a hand in almost every major contest of the period, including the series of high stakes North-South matches initiated in 1823.[23] With his family, J. Miles Selden, connected with the horse Trifle (fig. 2), managed Virginia and Maryland courses.[24] Jockey club rules in those states became models for both region and nation.[25] Kentuckian Willa Viley (1788–1865) was instrumental in laying out the first official race track in Lexington and was a charter member of the Lexington Racing Association. His stables produced Richard Singleton (Richard Singleton, with “Viley’s Harry, Charles and Lew” (fig. 3), who, at the time, was considered the greatest racehorse in the state. [26] Viley later parlayed his expertise into even better investments, becoming a partner in the syndicate of the stallion Lexington, which surpassed all horses of the era to become one of the most renowned Thoroughbreds of all time.[27] And Robert Aitcheson (R. A.) Alexander (1819–67), also of Kentucky, bankrolled the northern sporting periodical, Turf, Field and Farm, as well as the first official studbook.[28] These examples, coupled with Cohen’s research, counter established stereotypes of the aristocratic, but backward, southern sportsman or gambler and alternatively present the image of the calculating, increasingly modern entrepreneur, anticipating the Leonard Jeromes (1817–91) and August Belmonts (1813–90) of the Gilded Age. They further reveal that while southern racing retained some of its regional flavor, it had also begun to institute the mechanics of what would later define a successful, commercial—even modern—sporting enterprise, built and anchored by highly skilled African American labor. Troye’s animal and human group portraits emerge from this milieu, grounded in conservative aesthetic tradition but also connected to contemporary social impulses.

Towards Portraiture: Troye’s Trainers, Grooms, and Jockeys

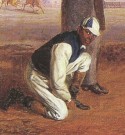

Black horsemen filled the racing world from the antebellum period through the beginning of the twentieth century. After the Civil War, African American jockeys won all the first runnings of the now-renowned Kentucky Derby and Belmont Stakes.[29] For the period prior to the establishment of these recognized races and the founding of The Jockey Club in 1894,[30] records are much scarcer, existing mainly in the pages of the sporting periodicals and in Troye’s paintings. The press frequently used racist language, extolling whites over blacks, and couching races as color competitions. But ironically, descriptors like “sable” or “darkey” helped contemporary historian Edward Hotaling to distinguish the sheer numbers of black athletes working in the antebellum racing world.[31] Some writers did give black horsemen their due, praising them for their skills and showmanship as well as referring to them by their given names. The jockey Cato’s name plastered press pages for months after he not only rode to victory, but also, it was rumored, to his freedom, in one of the biggest East-West matches of the century, on a Virginia-bred horse called Wagner, besting the Kentucky-bred Grey Eagle in front of a crowd of ten thousand at the Oakland course in Louisville in late September 1839.[32] William T. Porter, esteemed editor of both the American Turf Register and the Spirit of the Times and a race spectator, gushed that Wagner was above all “better managed and better jockied [sic]” than Grey Eagle, who had been ridden by a white jockey.[33] Of an engraving of the horse and rider, made after a painting by Troye, and published in both racing rags, he heralded that, “Cate-O stands out in pretty bold relief in the picture, as he does in the racing world. . . . As a jockey Cate-O has very few equals on this side of the Atlantic. He has a capital seat, is very strong in his arms and thighs” and possesses a “coolness and presence of mind” (fig. 4).[34] Troye’s paintings, I contend, can be read as contemporary visual pendants to press accounts of Cato, extraordinarily recording, as ordinary facts of life, such men, commended for their intelligence and ingenuity—their “coolness and presence of mind”—and their knack for tapping and developing equine blood, talent, and speed. According to Hotaling, “it would be hard to overestimate the contributions of . . . Troye in preserving the memory of those slave athletes.”[35] Indeed, Troye’s paintings survive as the primary visual evidence of African American athletes in the age before photography.

Should Troye’s depictions, however, be understood as portraiture? Many European and New World portraits of white sitters include the familiar convention of the black servant attending his or her master and signify not likeness, but the privilege, purity, and power of the white subject.[36] A portrait, in contrast, typically commissioned by the sitter or a friend or family member, intends to convey something of the sitter to the public. Gwendolyn Dubois Shaw, in her study of nineteenth-century African American portraiture, warns of misunderstanding the former—those pictures tied to the institutions of slavery, colonialism, and subjugation—as portraits.[37] William Henry Brown’s (1808–83) watercolor and cut paper collage Sarah Pierce Vick on Horseback (fig. 5), produced for the Vick family of the Nitta Yuma plantation in Warren County, Mississippi, epitomizes this custom of using the slave to symbolize the mistress’s power.[38] In raising the bucket to feed the horse Jake, the slave gestures toward his erect, regal mistress, who is riding sidesaddle and elegantly costumed in flowing black dress. She in turn reflects his action, yet her own gesture is one of dominance: her gloved, outstretched hand brandishes whip, leaving no doubt as to the bounds of her control over both beast and man.

In contrast, Troye’s paintings rarely include owners, but instead the people that rode and managed the horses.[39] Yet in Tobacconist, the jockey Ben, trainer Manuel, and horse shown together as a group of possessions still plainly signal John Minor Botts’s stature as an owner of fine horses—Tobacconist had just won the Newmarket plate—and accomplished slaves—allegedly Ben was Botts’s favorite jockey.[40] Ownership in Trifle, which depicts the mare accompanied by trainer, groom, and mounted jockey, is more convoluted and illustrates the intricate network of racial privilege that underpinned American antebellum racing. While the trainer and groom are slaves, John Charles Craig, the owner of the horse, did not own them, and the jockey would have been paid labor. Troye created the painting—one of nine that he would paint of Trifle but the only one with three human figures—during the summer that he traveled to Carlton, Craig’s farm in Pennsylvania. That it was in Troye’s Kentucky studio when he died indicates that he painted it for himself or was a copy he made to carry with him to showcase his skills.[41] Beyond its function as an advertisement, its web of relationships reveals the already complex nexus of the 1830s horseracing industry. In 1832, Craig owned the chestnut mare. Standing only fourteen and three-quarters hands tall, she won an astounding twenty races out of twenty-four starts in four years, the majority at four-mile heats.[42] Craig had purchased her the previous fall from J. Miles Selden at the Newmarket Course near Petersburg, Virginia, where Craig’s sometime partner, William Ransom Johnson, kept a training stable. Although the black groom’s name has been lost, the nattily attired figure holding Trifle is likely William Alexander, Selden’s slave trainer.[43] Here, he wears the trainer’s uniform worn at races—beaver top hat, white shirt, bright vest, velveteen trousers, and waistcoat—a highly artificial and alienating symbol of high-born tradition for these black horsemen who donned it. The jockey is probably Willis, who rode for Johnson, as he wears light-blue silks, Johnson’s racing colors. Selden often acted as Johnson’s deputy, when Johnson could not be present at a race.[44] So, it is likely that Craig owned the horse, but he raced her under Johnson’s colors and kept her under Selden and Alexander’s conditioning program. After the spring racing season, horses traditionally rested at farms, and Trifle went to Carlton for the summer of 1832, where Troye painted her.[45] Troye’s painting therefore depicts a horse owned by a northern patron, ridden by an Irish jockey, and trained by a southern slave. Viewers of the painting could have identified Willis, or at least recognized, by his silks, that he rode for Johnson. Alexander may have acquired a notable reputation because of his success not only with Trifle, but also with other Johnson and Selden horses. The painting, in part, thus functions as a tribute to Craig, Johnson, and Selden’s enterprise that included an eye for good stock as well as the business know-how to bring it to its full potential.[46]

In so doing, the painting underscores how, as historian Randy J. Sparks has argued, “the sizable investment in horse flesh would mean nothing unless the animals were well trained and ridden.” Experienced horsemen equaled horses that ran faster, won more races, and earned bigger purses. And, although slaves were not “precisely ‘bred’ for the race course,” owners often selected them, perhaps because of physique or demonstrable skill, to undergo a lengthy apprenticeship program with experts.[47] In March of 1832, the spring before Troye painted Trifle and Alexander, it was probably Johnson or Selden who advertised the trainer’s skills and services in the American Turf Register:

Worthy of Regard—William Alexander. A very judicious and worthy man, reared in the stables of Col. W. R. Johnson, and a first rate trainer, who finished off the “Trifle” that won the Jockey Club purse at the Central Course [Baltimore], is now, as then, Mr. Selden’s trainer. A few likely boys (from ten to thirteen or fourteen years old) will be taken, and under him, thoroughly instructed in the art of training horses for the turf;—they being bound for seven years to the business. Even those who are not in the way of bringing horses on the turf would do well to embrace the offer; as they would be sure to get first rate grooms. The knowledge of training the race horse thoroughly well is at this time a profitable trade, few others adding as much to the value of a slave, or to the productive capacity of a free laboring man.[48]

The groom in Troye’s painting may very well have been one of those boys sent to learn the ropes from Alexander, or brought up under Alexander in Selden’s stables, his education at a youthful age resembling the training program of his young equine charges. That the men in Troye’s portrait are visual analogies to Trifle is therefore supported by John B. Irving’s advice that there is much to be learned from the equine temperament—notably its obedience and docility—as the ideal horse, and by implication the ideal slave, is “content to lose his own identity,” and live and move by “the will of another.”[49] Indeed, both man and beast might share similar traits: docility and tractability as well as loyalty, muscle, and aptitude.[50] So important were these men to the success of their animals that it was not unusual for slave grooms, riders, and trainers to be sent to training stables with valuable Thoroughbreds, or sold multiple times to owners who coveted their abilities.[51] Johnson was offered five hundred and fifty dollars for his “boy Ben,” even without a guarantee of Ben’s health,[52] and thirty five hundred dollars for his slave trainer Charles Stewart.[53] Wade Hampton II (1791–1858) of South Carolina wrote to another racing man, Richard Singleton, appealing to hire his slave Cornelius.[54] Such specialized skills of course increased slaves’ values and rather than be sold outright, they were also hired out for profit.[55] Consequently, slave riders, trainers, and even adept grooms, like other skilled slave laborers, sometimes gained certain measures of independence and elevated standing on the farm or plantation because they were able to earn money, often enough to buy their freedom, and were allowed a degree of mobility. Willa Viley paid fifteen hundred dollars for his slave trainer Harry and, once freed, Harry reputedly earned five hundred dollars a year with Viley who continued his salary even when he became too old to work.[56] Slaves regularly crossed state lines with their equine charges[57], and Alexander may have traveled to Maryland and South Carolina since Johnson’s horses ran on northern and southern tracks. Evidence of Alexander’s history ends in 1832. He may have continued to train for Selden, as the Turf Register notice implies he would be there for seven years instructing the “few likely boys,” but the possibility exists that he was sold or bought his freedom at some point because a William or “Billy” Alexander was training for a Colonel Thompson of Arkansas in 1838.[58]

Alexander, like Trifle, is another prized commodity, amplifying Craig’s, Johnson’s, and Selden’s statures through his inclusion. His role in the painting as Trifle’s attendant conforms to the role of subordinate that, Elizabeth O’Leary has shown, African American workers and slaves regularly inhabited in American visual imagery of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[59] Adjacent to Alexander is the jockey Willis, pictured astride. A rider astride is a rare pose in Troye’s oeuvre because, scholars have claimed, he lacked the skill to paint it well. [60] Willis’s red hair and ruddy complexion suggest that he may have been of Irish descent, and in fact many Irish jockeys worked in the South as well as the North,[61] as they comprised, like African Americans, much of the available low-wage labor pool. While the virulent attacks on Irish Catholics and other immigrants in the decades following Troye’s painting were only simmering in 1832, both Alexander and Willis are depicted in subservient, laboring jobs that, during the period, would have been understood as fitting for the Irish and African Americans—both racial and ethnic minorities—to perform.[62] For Troye’s current and future patrons, then, an image like Trifle, in documenting a winning horse, could strengthen one’s reputation among one’s peers. It also, through its resemblance to early modern sporting art, could serve to reify a culture of European aristocratic privilege filled with loyal animals and servants for its white American, Protestant players in a sport that was steadily diverging from its kingly origins. Yet by including African Americans and Irish Americans in laboring positions, Troye squarely binds his picture to its setting, transforming the class-based social hierarchy, informed by colonialist and racial ideologies of Troye’s European model, into one delineated more explicitly by the racial and ethnic politics of antebellum America.[63]

Troye’s desire to capitalize on the American demand for English style imagery is evident in that he advertised his paintings as “after the style of Stubbs and Sartorius.”[64] And with Trifle, it seems, in complicating his composition by including both animal and human subjects, he drove home his mastery of his eminent English artist forebears and hoped to distinguish himself from competitors working in the states, such as the painters Alvan T. Fisher (1792–1863) and Henri Delattre (1801–76), or silhouette cutter Brown. Troye’s sophisticated understanding of equine anatomy likely came from his careful study of Stubbs’s Anatomy of the Horse (1766).[65] His debt to Stubbs is also evident in a copy of Stubbs’s Attack By a Lion Upon a Horse, which he exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1832,[66] as well as in the background of his portrait of the mare Bolivia (1836), which more closely resembles the English limestone cliffs of Creswell Craggs than the Alabama countryside where Troye painted her.[67] Tobacconist’s composition may even reveal a subtle reference to Stubbs’s Hambletonian, Rubbing Down (fig. 6), which depicts a top-hatted attendant who may be trainer-jockey Tom Fields who had resigned his position after a dispute with the horse’s owner just before Hambletonian’s celebrated race at the English Newmarket, then witnessed his former charge run to exhaustion in a painful victory under a new trainer.[68] In Troye’s portrait, Manuel’s pensive look and Tobacconist’s flattened ears suggest a similarly unpleasant battle, but instead at the Virginia Newmarket course. Yet beyond Troye’s obvious relationship to Stubbs in his handling of animals and their settings, his inclusion of attending figures and, most importantly, his individualistic treatment of them, signals that he brought to his pictures a deep understanding of the eighteenth-century artist’s interest in the laboring class.

Robin Blake attributes Stubbs’s interest in this subject to his early career as a jobbing portraitist as well as to his contemporary artistic and literary milieu, in which the lives and visages of servants appear as the subject of novels by Samuel Richardson (1689–1761), plays by John Gay (1685–1732), and portraits by William Hogarth (1697–1764).[69] Matthew Craske adds that the increasingly scientific approach to breeding and blood sports, characterized by interminable lists of bloodlines, game statistics, technical jargon, and other minutiae, carried across to the precise documentation of English estate servants, including descriptions of their habits and activities and records of their appearances. On paintings, it became fashionable to include servants’ names on labels or in titles, or in an accompanying key.[70] In Stubbs, period trends converged with his portrait experience, producing artworks that humanized servants. Blake asserts that:

England had never produced a more committed painter of the laboring class than Stubbs. His hunt servants, gamekeepers, stud-grooms, jockeys, stable-lads, tiger-boys, and farmworkers are neither patronized nor caricatured: they are studied presences, about whose features, clothing, and posture the artist has taken minute care.[71]

Hambletonian’s handlers exemplify such particulars: the slightly sweet expression of concern from the groom, his youth marked by a curling fringe of hair and dimpled chin, or the more sober form of the sturdy elder attendant, who calmly quiets the overwrought horse, whose foaming mouth, wide eye, and enlarged vein palpably convey his distress. Even when Stubbs includes an unnamed black groom, holding his master’s horse, in George Keppel, Third Earle of Albemarle, and Henry Fox Shooting Over Pointers at Goodwood, with Four Servants in Attendance (1759–60), he portrays him in a remarkably “unstereotyped” manner: costumed magnificently in yellow- and red-trimmed livery, with glinting earring, relaxed and patiently waiting for his gentleman to finish his shot and return to his steed.[72]

Blake’s characterization of Stubbs as a painter committed to creating humanizing portraits of both the anonymous and the identifiable workers who cared for the horses and grounds could just as readily be applied to Troye. Troye’s black trainers frequently turn towards the viewer, their frontal gazes coupled with their elegant costumes accentuating their roles in the paintings and in the stables. In Trifle, Alexander’s presence is also highlighted by the scarlet-trimmed blanket the groom bends to pick up. And, even though the jockey Willis is slightly above Alexander, astride the horse at the composition’s apex, Troye gives the men equal weight through their penetrating expressions and distinct faces.[73] Alexander looks outwards with deep-set, almond shaped eyes, under a wide forehead and well-defined brows. The red-headed Willis bears a ruddy complexion; his nose is long, almost too much so for his face. Troye’s candid portrayals of Alexander and Willis are examples of what Hotaling characterizes as Troye’s ability to see and portray “people as they were,”[74] even when such portrayals are complicated by the uniform clothing of jockey silks or trainer habit. This quality of candidness moves Troye’s pictures beyond a symbolic confirmation of the patron’s or horse’s cachet, or a codification of privilege, into the thornier arena of portraiture.

There are no reliable contemporary photographs of Troye’s human subjects that might shed light on the accuracy of his images and firmly establish them as portraits. Troye’s obituary stressed his anatomical fidelity, and his nephew in a biographical sketch of the artist concurred that, “Mr. Troye’s [animal] portraits were painted true to life.”[75] Many of his horses, however, look suspiciously alike, with full bodies, spindly legs, straight shoulders, and a “plumed waterspout tail.”[76] Yet Mackay-Smith has convincingly argued that critics who judge Troye’s bloodstock against horses today make an inherently flawed comparison, since the modern Thoroughbred looks little like that of the antebellum period. Troye’s recording of animal markings, coloring, and anatomy is quite reliable.[77] Should we, however, attribute the same accuracy to his human figures? The titles by which the paintings are known, which often include the names of jockeys and stableworkers in the English fashion, suggest their identities were important. Further, the individual nature of Troye’s human figures indicates that the artist made preparatory studies of them from life as he did of animals, and that he attempted to paint all of his subjects, no matter what their species or ethnicity, as objectively as his capabilities allowed.[78] In Tobacconist, Manuel wears long sideburns. His light coloring marks his mixed race, possibly of West Indian, ancestry. His facial hair sets off his high cheekbones and square jaw. In Trifle and Tobacconist, Troye distinguishes his darker-skinned figure from his mulatto or white counterparts by giving him a wider nose and fuller lips, but not exaggeratedly so. This is evident with trainer Harry and groom Charles in another of Troye’s group paintings, Richard Singleton, with “Viley’s Harry, Charles and Lew.” Here, Harry, saddling the horse, and Charles holding him, both with dark complexions, wide noses, full lips, and large eyes set with black pupils, possess the most “Africanized” features of Troye’s figures. It is certainly conceivable that Troye overstated, or even invented, their facial characteristics, in keeping with Frederick Douglass’s assertion, in an 1849 essay on “Negro Portraits” in The Liberator, that no impartial portraits of African Americans by white artists can exist, since white artists cannot help but distort and exaggerate features based on their engrained perception of black physiognomy.[79] But in this case, reading Harry’s and Charles’s faces as caricature-like seems more the result of a quickly finished, less finely modeled canvas than Troye’s reverting to types. The artist’s same loose, thick brushstrokes are evident in the horizon area under the horse’s head as well. That Troye documented these particular men—their faces, costumes, and gestures as carefully as he rendered the details of animal conformation and coloring—is consistent with the era and his patrons’ desires to establish, through material evidence, a legitimate history of the American Thoroughbred, originating out of, but distinct from, its English ancestors. Troye’s group paintings of Richard Singleton, Tobacconist, and Trifle thus build on and transform their English predecessors, as well as on generic master-slave imagery like Brown’s Sarah Pierce Vick and Jake, to offer uncommon portraits of non-domestic slave workers that suture the story of the American Thoroughbred to the institution of slavery.

In humanizing his servant characters, Stubbs humanizes their labor. Troye, in effect, likewise dignifies the labor his figures perform, but within the context of slavery. Ben and Cato have just ridden and Manuel and Alexander saddle horses—acts in a larger conditioning and performance program. And, even with their similarities to conventionally posed sporting art figures—standing next to or attending horses—Troye’s figures are not listless; most actively do something. As Kirk Savage has argued, to depict slaves in actual work was problematic because of the nature of labor: “For the slaves, work was at once an outside burden, imposed by the master’s will, and [my italics] an internal expression of skill and productivity, sometimes even creativity.”[80] It was therefore much easier for the pro-slavery faction to avoid the iconography of work altogether and to show slaves at only at play or at rest, because to show them involved in field or gang labor exposed slavery’s brutal, dehumanizing qualities, and to show them engaged in more privileged, skilled labor demonstrated their creative and intellectual capacities. In depicting the latter, Troye bestows on his subjects the dignity of performing quality work. Yet, not only is that work performed at the behest of others, it is non-productive because instead of training the horse for agriculture, it is for leisure and gambling—an activity off limits to African Americans and thus a “speculative economy whose rewards lie beyond their reach.”[81]

Troye’s images typically locate his animal and human figures in the foreground of his pictures, within or framed by a landscape. In certain instances, barns and outbuildings appear in the remote distance; in others, a fence divides the figures from a woodsy backdrop. All are what Ian Finseth has termed “racial landscapes,” which portray African Americans in a natural setting and invite viewers to analyze racial meanings encoded in natural iconographies.[82] As industrious slaves tending animals (albeit for a leisure economy) amidst manicured pastures, Troye’s images recast the myth of the idyllic plantation landscape with its rightful, aristocratic order. His figures are both nature and culture. In harmony with their surroundings, they compare to the animal—an oft-used manifestation of nature—they attend. In taming, grooming, and training the animal, they cultivate it into a cultural being. In this way, they are transformed into cultural agents, but of a culture in which in which they are marginalized and subjugated, in the service of their masters, the patrons and equines of Troye’s paintings. The fence, as Finseth argues, operates as a potent physical symbol of partition: it literally separates foreground (horse and human) and background (landscape) and thus separates nature and culture, but also metaphorically divides the cultural realm of the African American figures from that of the dominant culture.[83] Such a nebulous position, neither fully inside nor outside, is perhaps what makes evidence of these men’s existence, beyond sporting journal reports and Troye’s paintings, so hard to excavate. Rarely listed in inventories of house or field slaves, discussed in diaries, or documented in financial records, little tangible data exists that could shed light on where they lived on the plantations or what kind of communities they forged.

Troye’s pictures, in which trainers, jockeys, and other horsemen hold privileged positions also raise questions about how the hotly contested theory of exceptionalism[84] circulates around the artist’s portrayals of African Americans, many of whom were or had been recognized as skilled horsemen and athletes. Horses typically competed in three- and four-mile heat races, frequently running four heats in one day, with cool down periods of roughly thirty to forty-five minutes between heats. That means that winning equines and their riders might go twelve to sixteen miles per day, or twenty miles as Trifle did against Black Maria on October 13, 1832, and potentially race again the following week, grueling programs often condemned by the public for excessive cruelty.[85] In transporting horses, usually by foot, from race to race, preparing them, and then piloting them in races, these men also endured many arduous miles. In this way, Troye’s subjects conform to the limited roles, born of primitivist rhetoric and scientific studies attesting to blacks’ innate biological or physiological capabilities, that blacks have historically been able to inhabit, such as musicians, dancers, and athletes. The press even highlighted jockey Cato’s athleticism, his strong arms and thighs. By situating his subjects within the milieu of sport, Troye’s pictures reinforce another nineteenth-century visual tradition that, even when depicting African Americans in a dignified or sensitive manner, confines them to such roles, exemplified most notably by the music and dance-themed genre images of artists such as William Sidney Mount (1807–68) (Bone Player, 1856) and Christian Friedrich Mayr (1803–51) (Kitchen Ball at White Sulphur Springs, Virginia, 1838). Troye’s canvases, like those of Mount or Mayr, occupy an ambiguous space: simultaneously rehearsing and resisting stereotypes.[86] Troye’s equine pictures single out exceptional African American horsemen, but in doing so, dispassionately describe the sporting culture of the antebellum South, in effect merging genre and portrait sensibilities to reflect both norms and exceptions. In this way, Troye’s African American figures reveal what Richard J. Powell has called, “an idiosyncratic sense of subjecthood,” in that Troye is able to portray “real people” within an “embodied history and culture.”[87] Jon Entine and David K. Wiggins have discussed how various types of sporting events frequently took place among slaves on the plantation. Slaves staged their own impromptu contests, including horse races, and jumping, running, and swimming events; young slave children spent holidays playing sports, including ball-playing and foot races. Slave owners might also organize matches, though usually more combative ones involving boxing or wrestling, solely for whites’ enjoyment. [88] Troye’s subjects are those who deftly negotiated this plantation playing field, capitalizing on their talent and training to gain rank within it. Additionally, they often also moved decisively beyond this private landscape, segueing into the more formalized antebellum sporting arenas of the public racetrack and national sporting press.

Parson Dick of the Forks of Cypress, Loyalty Portraits, and Troye’s Sympathies

That Troye possessed an interest in a Stubbsian or broader eighteenth-century English artistic project of portraying the servant as a figure in his or her own right is supported by the resemblance of his painting of the slave Parson Dick (fig. 7) to various servant portraits such as Stubbs’s image of Thomas Smith, one of two Stubbs painted of Lord Rockingham’s banksman (c. 1765). Stubbs shows the elderly, dependable manager of the lord’s coalmines in half-length, dressed in a dark suit, set against a dark background. His gray hair and fleshy jowls reveal his age; his expression is world weary.[89] Troye’s canvas of Parson Dick, likewise, is a lovely small oil of a man alone, which portrays him without flattery and with no overt indication of his occupational role. Created with broad, loose strokes, its sensitive handling indicates that Troye endeavored to portray his subject with dignity. Parson Dick, thought to be of Creole descent,[90] seems every bit the aloof gentleman in blue suit coat and white cravat. His expression is composed and somewhat calculating, boldly meeting the gaze of the viewer, with wide eyes, aquiline nose, furrowed brow, and fashionable sideburns. His age looks to be about thirty. Parson Dick lived at the Forks of Cypress, a plantation complete with stables and racetrack, built by James Jackson (1782–1840), just outside of Florence, Alabama.[91] Troye may have first met Dick in 1838 when he came to the Forks to paint Leviathan, one of Jackson’s English import stallions, and again encountered him in 1842, two years after Jackson’s death and the year that his nephew and estate executor Thomas Kirkman, Jr. (1800–1864) invited the artist back to paint Glencoe, another import.[92] Dick, nicknamed Parson for the congregation he established on the property, shared with Troye a sound knowledge of horseflesh. The Jackson family purchased him in New Orleans, notably for his skill with the animals, and he quickly became a respected groom and handler at the Forks. He later served in the main house as carriage driver and butler.[93] A family biography states that Dick was a “stable boy until after the racing feature of The Forks was abolished,”[94] and historian Curtis Parker Flowers reasons that, based on Dick’s fine dress in the portrait, it dates from a period when he no longer worked in the barns.[95]

Troye executed his portrait of Parson Dick without a formal commission.[96] He may have admired Parson Dick or established a friendship with him while painting horses in the stable and staying in the house. It may also have been a study for a group portrait or conversation piece that was never created. Troye was no stranger to human portraiture; owners sometimes commissioned him to create likenesses of family members as well as livestock. He also began his career in Philadelphia, a prolific center of American portraiture, and likely came into contact with such eminent artists of the city as Thomas Sully (1783–1872) and with members of the Sartain and Peale families. Parson Dick may also have requested the sitting; certainly he evinces a strong sense of self-possession. Perhaps he helped Troye facilitate a sale, knowing the Jackson family’s high regard for his long-time service at the Forks. Indeed, family history reveals that the Jacksons liked the painting so much that upon its completion they purchased it, and it remained for many years in their home’s summer dining room. It was later passed on to descendants. In keeping with his time, Alexander Jackson, in his biography of his grandfather James, quixotically described Parson Dick as the devoted servant, who his grandmother thought would never leave. But while Dick certainly held a higher rank than most slaves, his life was controlled on many levels, and he disappeared on a visit to his wife at nearby Woodlawn plantation in 1865.[97]

Although the Jackson family may not have specifically requested Troye’s portrait of Parson Dick, it is connected to the “loyalty portrait” tradition in which families or businesses commissioned images of cherished servants or long-term, dependable employees. A significant body of these European portraits arose from the sporting genre. In the process of commissioning artists to depict favorite horses or dogs, employers also requested servant portraits as both subsidiary figures in larger compositions and as lone individuals.[98] Troye’s portrait of Dick came about through his commissions for the Forks of Cypress horses; the grandson’s fond memories of Dick and the painting’s placement in the summer dining room suggest it inspired similar emotions in family members. For other slaves and servants working in the house, it may have marked Parson Dick’s status and commemorated faithfulness.

Servant imagery in the United States, especially in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, follows many European conventions, but is complicated by a different socio-economic structure and the institution of slavery. In early American imagery, black servants and slaves regularly appear in portraiture as attendants to individual white sitters. In family portraits, white servants and black servants and slaves may be included as supporting members of the household. Both whites and blacks frequent genre painting, performing domestic tasks and haunting corners and doorways, often for comic or dramatic effect. Servant/slave types, largely defined by race and ethnicity, were also popularized: the Irish maidservant Bridget and the black kitchen maid Dinah.[99] Rare, however, are portraits of individual black slaves or servants. One example is Gilbert Stuart’s (1755–1828) Portrait of George Washington’s Cook (ca. 1795–97), which represents a man, who is presumed to be cook Hercules, in half-length, dressed in a white chef’s jacket and hat. As Shaw notes, his slight smile and direct gaze convey a note of individualism, but his identity is subsumed beneath his uniform that prescribes his duty and ownership.[100] In contrast is Susan Ridley Sedgwick’s (1788–1867) “exceptionally sensitive” watercolor on ivory miniature of Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman (1742[?]-1829) (Portrait of Elizabeth Freeman, 1811), the African American family nurse of Sedgwick’s sister-in-law Catharine Sedgwick (1789–1867), which depicts Freeman without any markers indicating job or duty. In her memoir, Catharine describes Freeman, who courageously brought suit against her old owners to win her freedom, as “the main pillar of our household.”[101] While certain reliable adjectives—loyalty, truth, perfect in service—dot Catharine’s praise for her nurse, Catharine also casts her as a person to admire for her intelligence and morality, qualities revealed in Susan’s portrait through Freeman’s steady gaze, conservative dress, and overall composure. Freeman was even buried in the Sedgwick family plot.[102]

Troye’s portrait of Parson Dick combines elements of the aforementioned European and American examples: emerging, like Stubbs’s servant portraits out of a sporting tradition, it remains a rare example of a sensitive, straightforward portrait of a slave, devoid of the trappings of plantation or household duty. Although what Parson Dick expected from his portrait or how he contributed to its appearance may never be fully determined, the Jackson family rewarded Troye for his careful interpretation of a man whose face conveys not unwavering devotion, but rather, what Flowers has aptly described as a certain disdain—an expression that, importantly, seems captured, rather than fabricated.[103] And, the Jacksons felt comfortable affording his visage a significant spot on the walls of their home. That he looks back, in a flash of recognition first enacted between himself and Troye, then between the slave and his owner(s), as Alex Bontemps describes, dissolves the “illusion on which enslavement by means of objectification was based . . . .”[104] By implication, Troye’s painting, as one of many portraits decorating the family mansion, functioned in part as a sign of upper-class respectability, but also confirmed the unusual standing that black horsemen held at southern plantations like the Forks of Cypress. For, as with Freeman’s burial, at the Forks of Cypress, during the stable’s zenith, the tradition existed for jockeys to receive burials in the Jackson family graveyard.[105] These markers (fig. 8), rectangular slabs set into the earth with long-gone inscriptions, if they ever possessed them, are determinedly more humble than the grand headstones of the white members of the Jackson family (fig. 9). However, the placement of the graves within the family’s private, walled cemetery clearly distinguishes these men from the plantation’s other slaves, who are interred nearby in the African American cemetery, located in what used to be an open field that is now covered with trees. The gravesites are marked with small, hewn, but not dressed, blocks of limestone.[106]

Because of his studied emulation of Georgian portraiture (equine and human), in his attempt to satisfy his patrons’ demands for images evoking the elite racing culture and class hierarchies of their forebears, Troye’s creation of an unusually sensitive body of African American portraiture may have been unintentional, the result of his being a sophisticated imitator. Yet a better interpretation is that Troye’s portrait of Parson Dick and his group paintings featuring jockeys, grooms, trainers, and animals instead reveal a cognizant response to his own personal experiences with his subjects, to southern American racing and the culture that sustained it, to contemporary portraiture and images of blacks, and to the socio-political upheavals surrounding slavery and the Civil War. From the racing and breeding records of the horses Troye painted, it is evident that the artist typically recorded those that had just won races or possessed accomplished breeding records. His reasons for including the various jockeys, grooms, and trainers, however, are less transparent. His compositions, in all likelihood, developed as dialogues between patrons and artist. Some jockeys, like Cato, performed phenomenally in press-acclaimed rides, or, like Ben, were favorites of their owners; the names of such trainers as William Alexander were equally recognized. Others won little notoriety. And certainly, Troye also painted hundreds of horses that were given brilliant rides without also including their brilliant riders. Consequently, one may never determine precisely why Troye included the specific people he did.

That many of Troye’s friends and patrons were southern slave owners suggests that the artist may have possessed similar beliefs in the legitimacy of slavery and the inferior status of blacks. John Davis argues that, “there is no question as to where [Troye’s] sympathies lay,” because of his close connections to Southerners—patrons, friends, and family—and because his will specified that his property, if he left no heirs, should be sold to benefit the orphans of Confederate Soldiers and the Sisters of Charity, “provided their sphere of operation is confined to the Southern States.” Further, the language used in Troye’s obituary, which describes his stint in Jamaica where he “had charge of” a sugar estate, signals to Davis that he actually served in the “notorious” capacity of overseer.[107] This latter claim may be a stretch since one of Mackay-Smith’s notes in the National Sporting Library states that Troye was the “bookkeeper,” not overseer, of the Jamaica plantation.[108] And, other factors indicate that Troye’s sympathies and therefore his attitude toward slavery may have been less clear cut. The artist was a Presbyterian, a denomination that experienced numerous sectional and ideological schisms over slavery, even though the southern churches chiefly espoused the necessity of the “peculiar institution” and opposed northern Presbyterians’ claims of its sinfulness.[109] He was also foreign, having been born in Switzerland and then spending his early life in England, a country that had made slavery illegal and with a powerful anti-slavery faction.[110] Troye’s will describes him as a native of Switzerland and a naturalized citizen of the United States of America, but Mackay-Smith searched in vain for proof of his naturalization and thus concluded that Troye was never officially naturalized.[111] Troye’s foreign status may have been the reason that Keene Richards deeded Troye his Kentucky estate during the Civil War, so that Richards could avoid its seizure by the Union army.[112] Such a close friendship with Richards, however, did not necessarily mean that he shared Richards’s ardent support of slavery, secession, and the Confederacy,[113] and indeed, John Hervey writes that Troye “was not a Secessionist, but a sympathizer with the Federal cause.”[114] Late in the war, Troye took refuge at Woodburn Farm with R. A. Alexander who, like Troye, also held foreign citizenship as he was a British subject with Scottish lineage, and was known as a Union supporter and strong anti-secessionist.[115] While Troye’s support of the “Federal cause” may have been focused on anti-secessionist interest in retaining the union of states, Hervey’s statement raises questions about Troye’s commitment to the Confederacy and its support of slavery. No extant documents indicate that the artist ever kept slaves, even though as a foreigner he could have leased them, or owned them under Kentucky’s Slave Codes.[116]

Building his career in the 1830s, Troye was thrown into the world of racing. In close contact with the moneyed players of the sport, he often stayed in his clientele’s elegantly appointed homes and maintained a public persona as the fashionably dressed artist of his 1870 photograph (fig. 10). In this way, he continued the traditions of his fellow European artists who became insiders to the sports they imaged, becoming members of hunting communities or companions to their squire patrons.[117] Yet, more like his subjects, Troye was controlled by the whims of his patrons and the circuit, trekking assiduously across the country, packs laden with paint and canvases, in pursuit of commissions. He possibly empathized with the equine handlers he met and established close friendships with them, as all spent long hours in the saddle and the stable and were, in many cases, similar in age. His painting of Parson Dick, and another early portrait, Medley and Groom (fig. 11), likely emerged from such a familiar relationship. Of this latter image, Hotaling describes the groom figure, Charles Stewart, as the “handsome trainer,” who “exudes a certain class,” to “almost steal the picture.”[118] Stewart stands gracefully at the head of Medley, the sinuous curve of his left arm balancing his right leg as he steps slightly forward in a classical pose, raising his hand to Medley’s bridle. His hair is longish, brushed back from his forehead, and he wears a thin mustache and goatee that emphasize his angular face. His reddish lips complement his café au lait skin tone and pick up the red brow band of Medley’s bridle. More is known about Stewart’s life than almost any other nineteenth-century black horseman because Harper’s New Monthly published an account of his life story in 1884. In it, Stewart recounts his rise from exercise boy through the ranks to become a freed, respected horseman. To designate Stewart as either a “groom” or “trainer” is actually somewhat misleading since, in 1832, when Troye painted him, he had already traveled all over the South and North to races and farms, managed a training stable with at least eleven employees, earned enough money to have an agent, and become a “stallion man,” entrusted by none other than the “Napoleon of the Turf” to transport horses for breeding. He later bought his wife out of slavery although he, himself, remained enslaved, training horses in Louisiana until Emancipation.[119] Troye probably painted Stewart with Medley the same summer that he created his first portrait of Trifle with Alexander and Willis, when Stewart took the horse from Johnson’s Virginia plantation to stand at stud at Craig’s Pennsylvania farm.[120] Five years later, Stewart literally walked Medley, as horses regularly traveled on foot, through the Cumberland Gap to another farm in Kentucky.[121] Johnson clearly trusted him immensely, with both money and horseflesh; this respect Troye deftly translated into a spectacularly fine portrait of man and horse.

Woodburn and the Civil War: Ansel, Brown Dick, and Asteroid

The press lauded Cato for his “coolness” and “presence of mind.” In The “Undefeated” Asteroid, with Ansel (His Trainer) and Brown Dick (Jockey) (fig. 12), Troye impresses upon the jockey Edward Dudley Brown (1850–1906) a similar cerebral consciousness of his critical role in piloting Asteroid through a series of hard-fought victories as well as an awareness of his position as an enslaved African American man caught up in the country’s present political upheavals. Born in 1850 in Fayette County, Kentucky and purchased in 1858 by R. A. Alexander of Woodburn Farm, Brown’s swift running abilities earned him the nickname “Brown Dick” after a racehorse of the same name. He started out as a stable boy but wound up as the stable’s premier jockey.[122] Freed following the Civil War and reclaiming his given name, he continued his career at Woodburn, then moved to the stud farm of Daniel Swigert (1833–1912), whose Kingfisher he rode to victory in the 1870 Belmont Stakes. After briefly riding Standardbreds to steeplechase, Brown switched back to Thoroughbreds, this time conditioning them. In 1877, his Baden Baden prevailed in the Kentucky Derby. Other horses he bought, developed, and later sold—Ben Brush, Spendthrift, and Monrovia—went on to capture Derbies, Belmonts, and the Kentucky Oaks.[123] At a point, he was one of the wealthiest African Americans in Kentucky.[124] As in several other Troye paintings, the groom’s name remains unknown, but the trainer is Ansel Williamson ([?]-1881), who came to Woodburn following stints working first for Thornton Boykin Goldsby at Summerfield in Dallas County, Alabama, where he trained the horse Brown Dick, then for Richards at Blue Grass Park in Kentucky, after Goldsby sold the horse. Williamson surely was the one to crown Brown with the nickname of his illustrious charge.[125]

Troye painted this image for Alexander, who commissioned many works from Troye beginning in the late 1850s.[126] Troye frequently stayed at Woodburn, sometimes so long that the manager once expressed he wished Troye would leave.[127] If Troye did not stay there while painting, he resided at Sunnyslope, the nearby farm of his wife’s niece.[128] From the time Alexander inherited Woodburn, he grew it into a leading racing and stock farm, with Thoroughbreds and trotters, shorthorn cattle, Southdown sheep, and hogs. He and his brother, Alexander John (A. J.) (1824–1902), who took over the farm after R. A.’s death in 1867, kept careful breeding records and staged annual bloodstock sales;[129] they also scrupulously documented their animals through imagery, first paintings then photographs.[130] Troye produced the bulk of his group pictures, featuring racehorses, riders, and handlers, during the 1830s at the beginning of this career. Asteroid dates to the last decade of his life and because of his frequent work for Alexander, Troye may have felt at liberty to experiment with a more complex composition as he did early on when he most needed to advertise his talents to solicit new patrons.

The events of the Civil War also likely contributed to Troye’s and his patron’s interests in adding a narrative component to the picture, and it seems that in doing so, Troye may have again thought of Stubbs’s vignettes. Signed and dated December 11, 1864, Troye’s portrait of the “Undefeated” Asteroid includes the distant barns and outbuildings of Woodburn along with four Confederate riders in the upper left along the horizon line. In September and early October of 1864, Asteroid won races in Lexington and Louisville. On October 22, Confederate guerrillas raided and confiscated Woodburn’s stock, including Asteroid.[131] They may have targeted Woodburn because of its foreign owner’s Union support or simply because of its reputation as a notable livestock and breeding farm. A week later, neighbor Warren Viley returned the horse after discovering and paying a ransom for him.[132] One can speculate that Troye began the painting in October but was forced to stop work on it because of the horse’s abduction.[133] Troye’s initial composition may have been inspired by Fisher’s painting of North-South match victor, American Eclipse (fig. 13). Both depict horses held by grooms, with accompanying trainers and jockeys, set against backgrounds punctuated with fields and outbuildings, although Troye’s image reverses the placement of figures and horse. Troye’s painting likewise includes a blanket, this time red with gold letters spelling out Asteroid’s name, in the right foreground of his picture; he moves Fisher’s kneeling groom to the opposite side of the picture and transforms him into jockey Brown, adjusting his spur or boot, rather than attending to the blanket.

In finishing or revising the canvas, after the horse’s return, Troye likely added the guerrillas for narrative spice. Through their addition, Asteroid becomes a double-scene or “time shift,” more in the vein of Stubbs’s Gimcrack on Newmarket Heath, with a Trainer, a Stable-Lad, and a Jockey (fig. 14) which shows, in its upper right, Gimcrack handily galloping to victory over three other horses by several lengths, and in the left foreground, standing, after his win, about to be rubbed down.[134] But rather than solely depicting the before and after of a race, Troye creates a vignette that marks the animal’s victories, and more broadly describes the conscription of horses and loss of bloodstock, as well as the changing status of the black horseman during the Civil War. Troye’s picture thus commemorates not only Asteroid’s and his human partners’ racing prowess, the original intent of the commission, but also his status as a kind of war hero. It further memorializes the fates of horses during wartime. Following another raid, in which Woodburn horses fared less well than Asteroid, Alexander shipped his most important stock to Illinois and Ohio.[135] Other Southerners, like Troye’s friend Richards, helped arm the Confederate cavalry with exceptionally pedigreed mounts.[136] Throughout the war years, Union and Confederate troops conscripted thousands of other horses, particularly blooded Thoroughbreds; many perished in battles, as well as from disease and starvation.[137] Brown’s pose, as well, proffers an additional story through its remarkable resemblance to the abolitionist emblem of the chained, kneeling slave (figs. 15, 16). This emblem could not have been unknown to Troye as it was the most widely circulated image of the antislavery movements in both Britain and the United States and the most successful through its iconography of supplication, meant to inspire sympathy rather than tyranny or hostility.[138] Troye, however, further adapts it, from a symbol of supplication into one of acuity, by portraying Brown actively engaged in adjusting his spur or boot, and also turning towards the viewer, seemingly prescient of, but slightly perplexed about, his changing status in the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation and his career trajectory in the post-Civil War horseracing industry. Troye’s composition fails to clarify whether Asteroid has just been ridden or is being tacked up. Is Brown getting to ready to mount Asteroid after Williamson saddles him for the race, or is he taking off his spur after Asteroid has just run and is about to be rubbed down and blanketed? On the brink, what comes next? During the late summer and fall of 1864, Brown’s status became even more uncertain as the war continued and Democrats nominated George McClellan (1826–85) as their candidate to run against Abraham Lincoln (1809–65). McClellan opposed the abolition of slavery; discussions also ensued about his commitment to preserving the Union amidst the party’s desire for an immediate end to the conflict.[139] Even after Lincoln’s election victory on November 8, would emancipation eventually come for Brown, Williamson, and the unnamed groom, and if so, how would it transform not only their lives, but also the landscape of Woodburn and its stables, operated by slave labor? Such questions were of the utmost consequence to the painting’s private audiences: to the men it depicted whose fates were in limbo, to an artist whose livelihood rested heavily on the patronage of Southerners and the horses they owned and raced, and to a patron and his family with conflicted allegiances to the Union, their neighbors, and state.[140]

Brown’s precarious position also resembles that of his mount. Although his experience with horses allowed him more autonomy than other slaves, his owners and labor circumscribed his life. Likewise, Asteroid’s pedigree had been calculated to produce speed and stamina; he was stabled, fed a strict diet, conditioned at regular intervals, and raced when adequately prepared. Even when flying at top speeds, he ran, not with abandon, but around an oval track, in the same direction, boxed in by rails, and urged on by whip and spur. At Woodburn, both Asteroid and Brown probably experienced an even more structured existence than other horses, grooms, and riders, as Alexander had transformed his stock farm into a highly sophisticated organization. In addition to his careful documentation of pedigrees, he was one of the first to segregate animals according to type and sex in different barns and pastures in order to insure the purity of bloodlines. He also implemented a more precise training system, known as clockwork, by which horses trained not against each other but against the clock.[141] Asteroid’s impending capture by the Confederate raiders would catapult him into a radically different environment, distanced from his cosseted world and transformed into a beast of burden. For his southern rescuers, returning him to the security of the plantation saved him from a miserable existence, or worse, a painful death, a story remarkably evocative of the paternalist rhetoric about blacks espoused by the pro-slavery faction. No matter Troye’s personal views, his painting articulates competing contemporary debates surrounding slavery in acknowledging the capability and humanity of his figures, and the deep-rooted anxieties about African Americans after emancipation. Like Asteroid, any agency Brown may possess is thus still limited, as while he may have some control over charting his future, and history reveals that he did, his fate is still very much bound to the circle of white privilege for and by whom his image was created. Ultimately, Brown’s image is both portrait and representation: a likeness and multivalent, though conflicted, political symbol.

In the end, the Civil War radically altered the landscape of the American racing industry, with horses lost, southern owners financially ruined, and African American slave riders and stable workers freed. Williamson eventually left Woodburn, but continued to work in southern stables. Brown left Woodburn, too, after it transitioned from a racing into a breeding enterprise. Successful for many years, he died impoverished.[142] His decline corresponds to the development of the industry that saw the disappearance of African American riders and trainers. Racism and segregration marginalized many; their dwindling numbers also resulted from migration to urban centers, which took them away from the rural sites of many horse breeding and training operations. Anti-gambling legislation finally forced the ultimate downfall of the racing industry in 1908; its incipient return as an even more lucrative sport involving agents and bigger money—as we know it today—resulted in the near total erasure of African American riders.[143] Some of the best known, most popular images of African Americans involved in racing and other equine sports emerged in this post-Civil War, transitional era, notably in Currier and Ives’s Darktown Comics. Throughout this series, African American characters ludicrously attempt imitations of such aristocratic equine pastimes as racing and hunting (fig. 17). Produced from the mid 1870s to the early 1890s, the Darktown Comics symbolize how visual culture became an entrenched means and indispensable tool for repressing African Americans in post-Reconstruction, Jim Crow America, and visually codified many of the stereotypes conceived on the minstrel stage and other popular entertainments, as well as in literature and political rhetoric.[144] This period likewise produced the denigrative lawn jockey, an ornament that saw its popularity ignite during the twentieth century, especially after World War II with the rise of the suburban landscape.[145] Troye’s portraits of horsemen present marked contrasts to those figures that inhabit Currier and Ives’s Darktown or haunt suburban doorsteps. His portraits illustrate how imagery of African Americans during the antebellum and Civil War years could function on multiples levels, often reinforcing artificial social and racial hierarchies while simultaneously distinguishing slaves as serious, competent, and intelligent persons, many with renowned reputations. Working partly by his patron’s requests, and partly on his own initiative, Troye created paintings that lauded horses’ reputations and worth, and glorified their owners. These images, as ambiguous, problematic, and inconsistent as they may be, also celebrate the trainers, riders, and grooms, and remain the primary visual records of the African American labor and expertise that built, sustained, and shaped the sport of American Thoroughbred horseracing.

Many thanks to all those who aided my research and made the publication of this essay possible: Petra ten-Doeschate Chu, Isabel Taube, and Robert Alvin Adler of NCAW; the anonymous reviewers; Ms. Curtis Parker Flowers of Florence, Alabama; Dr. Mitchell Merling, Paul Mellon Curator, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia; and the staffs of the following: National Sporting Library, Middleburg, Virginia; Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia; Kentucky Historical Society, Frankfort, Kentucky; and Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut.

[1] The most comprehensive inventory of Troye’s works is included in Alexander Mackay-Smith’s The Race Horses of America, 1832–1872: Portraits and Other Paintings by Edward Troye (Saratoga Springs, NY: National Museum of Racing, 1981), 411–36. It lists twelve that contain a single figure—groom or jockey—and horse. The other five contain two or three figures—groom, jockey, and/or trainer—and horse. Of these paintings that Mackay-Smith documents, the whereabouts of several are unknown. The men’s ethnicities are also sometimes in doubt and extant records frequently provide contradictory information.

[2] Richmond Jockey Club, Records, 1824–1838, Mss4 R4153 a 1, Manuscript Collection, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, VA.

[3] “Death of Edward Troye,” Turf, Field and Farm, August 7, 1874, 100; and “Sketch of Edward Troye and His Works,” unpublished manuscript from Van Shipp family, Harry Worcester Smith Papers, National Sporting Library, Middleburg, VA.

[4] Genevieve Baird Lacer, Edward Troye: Painter of Thoroughbred Stories (Prospect, KY: Harmony House Publishers, 2006), 25–26; and Mackay-Smith, Race Horses of America, 123–27.

[5] Mackay-Smith, Race Horses of America, 127–28, 153–57.

[6] “Death of Edward Troye,” 100. For an account of Troye’s Holy Land paintings, see John Davis, The Landscape of Belief: Encountering the Holy Land in Nineteenth-Century American Art and Culture (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 127–48.

[7] Mackay Smith, Race Horses of America, 355; Lacer, Painter of Thoroughbred Stories, 27; and J. Winston Coleman, Jr., Edward Troye, Animal and Portrait Painter (Lexington, KY: Winburn Press, 1958), 32.

[8] Harry Worcester Smith, “Edward Troye (1808–1874), Painter of American Blood Horses,” The Field, January 21, 1926, 96–98; Harry Worcester Smith, Catalogue of Loan Exhibition of Paintings by Edward Troye, 1808–1874 (New York: Newhouse Galleries, 1938); Harry Worcester Smith, “The Best of These Was Troye,” The Spur, January 1939, 41, 47–48; and Charles Cort, “Edward Troye in Alabama,” Alabama Heritage 80 (Spring 2006): 18–24. Smith and other such collectors as J. J. McGough purchased all the Troye pictures that the Troye descendents possessed, probably paying sums far less than the paintings’ worth. In one case, Smith convinced a Mobile woman, through an outright lie, that Troye used pigments that fell off the canvas so that she would part with her painting. Charles Cort, “Exploiting the Troye Legacy,” Alabama Heritage 80 (Spring 2006): 25. Correspondence reveals that Anna Troye Christian (1844–1924), Troye’s daughter, deeply regretted selling her father’s works. Letters to J. J. McGough, March 30, April 15, May 26, June 21, 1922, Harry Worcester Smith Papers, National Sporting Library, Middleburg, VA.

[9] Mackay-Smith, Race Horses of America; Coleman, Edward Troye; and J. Winston Coleman, Jr., Three Kentucky Artists: Hart, Price, Troye (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1974).

[10] Lacer, Painter of Thoroughbred Stories.

[11] Matthew Craske, “In the Realm of Nature and Beasts,” in Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits, ed. Giles Waterfield and Anne French, exh. cat. (London: National Portrait Gallery, 2003), 153–65.

[12] Ibid., 157.

[13] Alain Locke, The Negro in Art: A Pictorial Record of the Negro Artist and of the Negro Theme in Art (1940; repr., New York: Hacker Art Books, 1968), 139.

[14] The sport briefly collapsed during the economic depression of 1837. John Eisenberg, The Great Match Race: When North Met South in America's First Sports Spectacle (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2006); and Steven A. Riess, City Games: The Evolution of American Urban Society and the Rise of Sports (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 24–25.

[15] For a thorough account of his numerous patrons and the sporting press clients, see Mackay-Smith, Race Horses of America.

[16] Richard F. Floyd, “Proposition to the Animal Painters of the United States,” Spirit of the Times, July 8, 1843, 223.

[17] Around 1822, J. S. Skinner’s Sporting Olio of his American Farmer became a forum to rectify erroneous pedigrees; at the same time, several horsemen attempted to create private studbooks. Fairfax Harrison, Roanoke Stud: 1795–1833 (Richmond, VA: Dominion Press, 1930), 43. Race reports, animal portraits, pedigrees, and extracts of local and state jockey club minutes can be found throughout The American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine and Spirit of the Times: A Chronicle of the Turf, Agriculture, Field Sports, Literature and the Stage. After decades of failed attempts to publish an official studbook, Sanders D. Bruce finally produced the first that was generally accepted by turfmen in 1868. William Spencer Vosburgh, Racing in America, 1866–1921 (New York: The Jockey Club, 1922), 46–47. John B. Irving, The South Carolina Jockey Club, collects the history of his state’s club (1857; repr., Spartanburg, SC: The Reprint Company, 1975).

[18] John Stuart Skinner began publishing the monthly American Turf Register and Sporting Magazine in Baltimore in 1829. William T. Porter launched a New York-based rival, the weekly Spirit of the Times: A Chronicle the Turf, Agriculture, Field Sports, Literature and the Stage, in 183. Mackay-Smith, Race Horses of America, 445; Sanders D. Bruce, American Stud Book, vols. 1–2 (New York: published by author, 1873).

On the Jockey Club, see Melvin Adelman, “Quantification and Sport: The American Jockey Club, 1866–1867: A Collective Biography,” in Sport in America: New Historical Perspectives, ed. Donald Spivey (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985), 51–71.