The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Men lingered . . . for hours, and went away but to return. It [A Huguenot] had clothed the old feelings of men in a new garment, and its pathos found almost universal acceptance.

— F. G. Stephens, R. A. review, 1852[1]

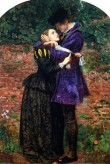

F. G. Stephens’s striking account of the reaction of nineteenth-century male viewers to John Everett Millais’s (1829–1896) A Huguenot, on St. Bartholomew’s Day, Refusing to Shield Himself from Danger by Wearing the Roman Catholic Badge (fig. 1) is surprising given current assessments of the painting. A Huguenot has been read as an early example of Millais’s courting of popular opinion, playing to the taste for sentimental or melodramatic pictures among Victorian critics and exhibition goers, especially in relation to the market for popular prints.[2]A Huguenot was the first of Millais’s paintings to be purchased by a dealer with the aim of making good his investment through print publication.[3] This commercial tendency in Millais’s work is understood as culminating with Bubbles (1885–86), a painting used, with the artist’s permission, as an advertisement for Pear’s soap, an incident that has overshadowed Millais’s artistic reputation, and has only recently been the subject of scholarly reassessment.[4] With this turn to commercialism, a reorientation towards a female viewer—who is responsible for moral improvement and cleanliness within the home—rather than a male viewer is implied. This same shift from male viewing subject to female consumer is subtly registered in the re-titling of the work when published as an engraving in 1856. The original more general reference to A Huguenot, the indefinite article suggesting a representative, even potentially shared, experience, was altered to the definite article, The Huguenot, suggestive of a specific individual confined to a particular historical moment. By taking Stephens’s account as a starting point, this investigation seeks to recuperate what was so revelatory and transformative, but ultimately unifying, in Victorian middle-class male viewers’ experience of A Huguenot.

Historians such as Leonore Davidoff, Catherine Hall, and John Tosh, and literary critics such as Herbert Sussman, Martin A. Danahay, and James Eli Adams have brought to light the complexity and fluidity of definitions of middle-class masculinity in the nineteenth century.[5] At the time Millais was working on A Huguenot the impossibly static ideal masculinity that nineteenth-century critics and commentators seemed to imagine: Protestant, publically upstanding and physically robust, was perceived to be under attack. The so called Papal Aggression led to fears of the spread of Catholicism in Britain, while revolutions abroad and social unrest at home led to questions being asked about the ability of the middle and upper classes to maintain order if a violent uprising occurred. These questions were prompted by an expanding class of physically inactive desk-workers, and the growing cult of domesticity, which privileged home-life over engagement in the public sphere. Viewed in relation to these contemporary concerns Millais’s A Huguenot can be read as a locus for anxious masculine self-regard, played out through a complex encounter with the feminine.[6]

To date, A Huguenot has received less scholarly attention than other works by Millais, such as Christ in the House of his Parents (R. A. 1850), Autumn Leaves (R. A. 1856), and Cherry Ripe (1879). The work was exhibited at the same Royal Academy exhibition as Millais’s acknowledged masterpiece Ophelia, which, unlike its companion, was presented to the National Gallery by Henry Tate in 1894, and today enjoys popular acclaim among visitors to Tate Britain.[7] William Holman Hunt’s suggestion in his autobiography that A Huguenot was seen by Millais as a “make-weight,” of secondary importance to Ophelia, which Hunt states Millais relied upon “for the advancement of his reputation,” may also have affected scholarly interest in the work.[8] Susan P. Casteras’s 1985 article, “John Everett Millais’s “Secret-Looking Garden Wall’ and the Courtship Barrier in Victorian Art,” and Paul Barlow’s brief but insightful analysis in Time Present and Time Past (2005) are therefore exceptions in the scholarly literature.[9] Casteras positions A Huguenot as an innovative contribution to the well-worn theme in British art of two lovers meeting at a style, gate, or wall; in Casteras’s terminology a “courtship barrier.” Her findings point out how this painting is far from conventional in its treatment of gender at mid-century.[10] Barlow provides a subtle formal reading of A Huguenot.[11] He emphasizes how the intertwining of the two figures is mirrored in the ivy and foliage in the background, noting how the painting explores the theme of “entwined lovers locked into wider natural processes of growing and intertwining forms.”[12] This article finds more evidence for his alternate reading of the couple’s embrace, “They wrap each other up, but also pull in opposite directions,” which draws attention to the defining, but simultaneously destructive relationship between the genders found in this image.[13]

Rereading A Huguenot

Millais’s A Huguenot depicts a man and woman in sixteenth-century costume against the backdrop of a minutely observed ivy and lichen covered brick-wall. The title of the work and the quotation from Anne Marsh-Caldwell’s book The Protestant Reformation in France, or, the History of the Hugonots [sic] (1847), which appeared alongside it in the Royal Academy catalogue, reveal that the painting depicts an incident occurring on St. Bartholomew’s Day 1572, when a massacre of Protestants took place in Paris during the Wars of Religion following the Protestant Reformation.[14] These texts also inform viewers that the white scarf the woman is attempting to tie around the man’s arm is the identifier of Roman Catholicism, and would therefore act to shield him from harm during the coming massacre. The man’s refusal of this badge would result in certain death. It is possible that the woman in the painting is wearing a white scarf around her left arm hidden behind the man’s body. Despite a lack of conclusive evidence within the painting or the title and quotation in the catalog, critics at the time stated, with rare exception, that the woman is Catholic, and that the lovers are therefore a kind of Romeo and Juliette, divided not by feuding families but by warring faiths.[15] Therefore, the Huguenot in Millais’s painting is depicted at a crucial moment of choice between earthly love and spiritual devotion. Millais leaves the outcome of this struggle open to question, although most critics tended to assume that the man’s faith would win out, often citing his calm demeanor as evidence of steadfastness in contrast to the woman’s more emotional expression, which speaks of grief and tragedy.[16]

J. G. Millais, in his biography of his father, provides the following commentary: “The women in “Ophelia’ and “The Huguenot’ were essentially characteristic of Millais’s Art, showing his ideal of womankind as gentle, lovable creatures.”[17] A few paragraphs latter he adds: ““The Huguenot’ was the first of a series of four pictures . . . each of which represents a more or less unfinished story of unselfish love, in which the sweetness of woman shines conspicuous.”[18] This influential assessment echoes the reviews which appeared after A Huguenot was first seen at the Royal Academy.[19] These responses, focused on ideal femininity, mask or perhaps more accurately deny the fact that masculinity is a quality just as much at stake in these works. Victorian critics read idealized femininity—patient, loving, loyal, and sometimes brave—as an unproblematic constant in A Huguenot and across the series listed by J. G. Millais as dealing with similar subject matter: The Proscribed Royalist, 1651 (R. A. 1853), The Order of Release, 1746 (R. A. 1853), and The Black Brunswicker (R. A. 1860). However, reading these paintings as homilies on conventional femininity disguises the less palatable narratives, available but submerged in these works, of troubled masculinity. In each of these paintings men struggle, with varying degrees of success, to define themselves as men against the forces of history and idealized femininity. In this way A Huguenot can be read as a reflection of masculine struggles, obscured by and diverted through the feminine. Encouraged by Stephen’s comments, the negation of women in the titles of these paintings indicates what we might alternatively look to in these works to understand how they functioned for Victorian audiences as more than sentimental keep-sakes.

Reviews of A Huguenot from 1852 help shed light on the extent to which the masculinity depicted in this painting is conflicted and could provoke anxiety among contemporaries. Critics focused on the manly stance of the Huguenot, which takes on an almost phallic resonance: he is repeatedly described as “firm” or “stiff”; but equally equivocation is registered as he is described as “tender” in his firmness.[20] In addition, several writers fixed on the question of the position of the Huguenot’s right leg, which is hidden behind the woman’s skirts. A critic for the Art Journal complained: “If there be any indication of his right leg, it is not sufficiently obvious”; the Times noted “his right leg has disappeared altogether,” while the reviewer at the Athenaeum commented: “additional awkwardness arises in the attitude of the lover from only one of his legs being shown.”[21] The missing limb becomes a focus for the fear of disempowerment and castration. Millais’s Huguenot in fact faces a double threat, the resolution of which the painting tantalizingly leaves in the balance: either death at the hands of the Catholics should he refuse to wear their badge, or the dissolution of his manliness by succumbing to female entreaties to deny his faith. In this sense the woman is as threatening as the swords of the Catholics; she has the power to emasculate him through her love by making him a coward.[22] A close reading of these reviews gives some indication of the complexity of the gender relationship at work in A Huguenot, which is in need of further explanation.

As Sussman observes in his discussion of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, the challenge Millais and his contemporaries faced was to depict in their art and enact in their lives a new model of masculinity at a time that witnessed the emergence of a powerful and prosperous middle class who measured success through achievement in business and industry. This new model of masculinity departed from previous military, aristocratic, gentry, or artisan modes, and laid increased stress on matrimony and the domestic sphere separate from the homosocial world of work. Sussman points out how this created tensions; he writes that there was “covert apprehension about a life lived outside a self-engendered male community” and that “bourgeois marriage [was] sapping male energy and domesticity vitiating male creative potency.”[23] Tosh sums up this dilemma succinctly, and particularly pertinently in relation to the choice faced by Millais’s Huguenot; he writes that for middle-class Victorian males “Becoming a man means leaving women behind.”[24]

A Huguenot engages with this theme. Millais’s painting shows the moment when the Huguenot must choose between his Calvinist faith and his love for a Catholic woman. If he resists the woman’s pleading, the outcome anticipated by Victorian critics, the Huguenot will successfully confirm his masculinity by leaving the female space of the walled garden implied by the ivy covered wall, and moving into a public sphere of homosocial relationships between men, defined by faith and by violence. If he gives way to the woman’s pleading, he will not be killed, but will perhaps face a fate worse than death, losing his masculine identity by defining himself through heterosexuality and matrimony, and tied to the domestic sphere. By depicting this moment of choice Millais skillfully avoids an irresolvable conflict with regard to masculinity, but it lurks just below the surface and comes to light in the critics’ allusions to firmness, missing limbs, and powerful, yet lacking, femininity. Drawing on Barlow’s approach to this painting, we might even sense this tension in visual form elsewhere in Millais’s canvas. Ivy, moss, and other weeds appear to be in the process of covering the crumbling brick wall; the forces of nature, traditionally seen as feminine, threaten to overwhelm culture, traditionally seen as male. The red petals that have fallen onto the ground and onto the Huguenot’s black shoe can be read as prefiguring the blood which will be spilled in the coming massacre, but could also hint at the result of sexual relations with a femme fatale. A contemporary critic observed that the Huguenot is caught in a “struggle between love and creed:” one leads to the loss of masculine identity, and the other to loss of life.[25] In Millais’s painting the Huguenot hangs between these two mutually exclusive choices that remain forever in play, and forever unresolved.

Masculine Heroics, Les Huguenots, and Papal Aggression

The fact that the male figure emerged for critics as the albeit uneasy hero of Millais’s painting is all the more noteworthy given the quite different outcome of an almost identical story of sixteenth-century lovers that was very well known at the time and is often mentioned as a potential source for the subject matter of A Huguenot: Giacomo Meyerbeer’s opera Les Huguenots, which ran from 1848 through 1852 at the Covent Garden Opera House in London. Intriguingly, none of the contemporary reviews located in the course of researching this painting refer to Meyerbeer’s opera, which highlights heroic femininity as much as, if not more than, heroic masculinity. J. G. Millais later denied that his father had used the opera as a source (contradicting both Hunt and an article that appeared in Chambers’s Journal in 1902), claiming that his father did not see the opera until after the painting’s subject was decided.[26] Perhaps as a result of his son’s comments, some confusion has arisen in the secondary literature as to whether or not the action of the tying of the white scarf, which Millais makes the focus of his painting, appeared in the opera.[27] As Malcolm Warner correctly notes, the opera does include a scene where a scarf is offered by the Catholic heroine to her lover.[28] Significantly, the Italian libretto describes the scarf as “bianca”—white.[29] The closeness of the incident that Millais depicts to the climactic scene in the opera, particularly the selection of a white scarf rather than some other token and in preference to the “strip of white linen” cited in the quotation he selected for the Royal Academy catalogue by Marsh-Caldwell, suggests that J. G. Millais may have been mistaken in denying the opera as a source for the painting. Perhaps more significantly, the quotation from Marsh-Caldwell’s book does not provide the dramatic context of lovers divided by religious faith. In fact this quotation from a historical source (since Marsh-Caldwell is herself quoting the proclamation of the Duke of Guise) may even have served to deflect critics from referencing Meyerbeer’s opera, which would have provided a ready-made romantic ending for the lovers’ story.[30] In Les Huguenots, after the Protestant, Raul, refuses to convert to Catholicism or wear the white scarf, thereby condemning himself to death, his Catholic lover, Valentina, converts in order to die alongside him. They hastily marry, and at the opera’s finale both are murdered while experiencing an ecstatic vision of heavenly glory. A reference to Meyerbeer’s opera would therefore have closed down the open-ended narrative of Millais’s painting, which allowed for the cathartic play of masculine anxieties defined previously.

Was there a further motivation on the part critics in the summer of 1852 to negate Meyerbeer’s proposition that a Catholic woman might risk eternal damnation in hell by becoming a convert to Protestantism for the love of a man who had refused such a sacrifice for her, and instead focus on steadfast masculinity resisting the feminine influence? One explanation for the critics’ and also Millais’s own insistence on the latter outcome was the recent bitter controversy over the so-called Papal Aggression of 1850–51. On September 29, 1850 Pope Pius IX reestablished the Catholic hierarchy in England after nearly three centuries. This move was particularly controversial not simply due to popular anti-Catholic sentiment in England, which dated back to the time of the Reformation, but also in the context of the large numbers of Irish immigrants who had arrived in England the 1840s, high-profile Tractarian conversions to Catholicism (for example that of John Henry Newman), and Louis Napoleon pandering to the Catholic vote in France.[31] Journalists seized on the wording of the Papal decree and the first pastoral letter written by Nicholas Wiseman, the newly appointed Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, as identifying an intention by the Vatican to challenge royal authority, scorn the Church of England and even interfere with the governing of Britain. Immediately a popular “no popery” movement sprang up spawning petitions, pamphlets, and even violence; on Guy Fawkes Night effigies of Wiseman and Pius IX replaced the traditional “guy.”[32] The popular outcry was quickly contained and tempered by calls in print for tolerance and an end to bigotry.[33] However, in this context, a painting which depicted a Catholic woman in a favorable light, and sidelined masculine Protestant heroics, might have met with a hostile reaction. Therefore it would have benefited Millais to distance his painting from Meyerbeer’s opera. Even if the Les Huguenots is seen as a merely coincidental parallel to the subject matter of the work, critics nevertheless refused to consider that the woman depicted by Millais, whom they presumed to be a Catholic, could emerge as a heroine.[34]

The backdrop of the Papal Aggression may also have raised more sinister contexts for the Catholic woman’s action of romantically and literally binding the male figure in Millais’s painting. The sensuality and seductiveness of the Catholic religion was repeatedly foregrounded in the often hysterical response of the press to Pope Pius’s actions. Journalists stressed how young, innocent and often wealthy middle- and upper-class English women of marrying age were being persuaded or forced into entering Catholic convents, undermining Protestant patriarchy.[35] Such stories staged the struggle between Protestantism and Catholicism in gendered terms with the virginal female body as the site of conflict. If related to the struggle depicted in A Huguenot, the woman can be read as the embodiment of the seductive qualities of the Catholic faith which threatens to undermine the power of Protestant males. Her action of binding the arm of the man recalls the violent yet clearly titillating episodes described in infamous anti-Catholic narratives such as Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, as Exhibited in a Narrative of Her Sufferings During a Residence of Five Years as a Novice and Two Years as a Black Nun, in the Hotel Dieu Nunnery in Montreal, the publishing phenomenon which first appeared in 1836 and sold 300,000 copies by 1860.[36] At the height of public outcry over the Papal Aggression in 1851 this volume was reissued in London in several different editions.[37] In this book Monk, alleges that nuns at the Hotel Dieu convent in Montreal, Canada, were forced to perform sexual favors for priests, with frequent institutionally-endorsed infanticide as the result.[38] The narrative dwells on the repeated humiliation and torture of the nuns, and in one episode a nun is smothered to death in a bizarre orgy.[39] The book also describes how the nuns were frequently tied up and gagged.[40] The seductive yet violent acts detailed in this narrative are recalled in the tender look but restrictive binding of the woman in Millais’s painting.

A Huguenot and the Visual Culture of 1848

The masculine dilemma that Millais’s A Huguenot covertly portrays—the need to balance homosocial, mutual recognition among men with heterosexual marriage and domesticity—had been rehearsed very publically in the popular visual culture of 1848.[41] The visual culture created in reaction to the threat of revolution engaged with similar themes often pictured by strikingly similar compositional means to those found in Millais’s painting. Caricatures repeatedly depicted the problematic transition for middle-class males from the domestic to the public sphere, from feminized to masculine spaces. As Tosh observes, in this period the “heavy moralizing of home ties conflicted with . . . longstanding aspects of masculinity . . . homosociality” and “the traditional association of masculinity with heroism and adventure.”[42] With this in mind an analysis of themes found in humorous images of middle-class men in 1848 can shed new light on A Huguenot.

Early in 1848 monarchies toppled as revolution swept Europe; at the same time, Britain witnessed a surge in support for the Chartist movement, and the mood was such that revolution seemed possible, and even imminent. It was feared that a mass demonstration of Chartists planned for April 10, beginning with a rally on Kennington Common followed by a march to Westminster, might spark a violent uprising in London. To support the police in their duties, approximately 80,000 special constables (sometimes called “specials”) were sworn in to keep the peace and protect property.[43] Most of these specials were drawn from middle-class occupations, although several other sections of society were also well represented among their ranks.[44] Ultimately, the April 10 demonstration, which Millais and Hunt witnessed in person, was seen as a failure; the police kept the marchers on the south side of the Thames away from strategic landmarks and the center of power, and the crowd dispersed with limited violence.[45] Although sporadic rioting occurred in the East End of London, throughout the summer months key Chartist leaders such as Ernest Jones and William Cuffay were arrested, and the danger of revolution was seen to have passed.[46]

Perhaps because of the chimerical nature of the Chartist threat and a general sense of relief that revolution had been avoided, humor was a predominant reaction in British visual culture to the events of 1848. Chartists and special constables, those who had taken the events of 1848 most seriously, were ridiculed in the satirical illustrated press and in popular culture more broadly. This satire often revolved around gender. For example, in a play at the Olympic Theater titled The Special the lead female character cross-dresses as a special for romantic intrigue.[47] Middle-class special constables were portrayed as physically ill equipped to deal with threats from working-class Chartists as bourgeois bodies shaped by desk work were depicted as inadequate when faced with work-class bodies toughened by physical labor. A typical satirical representation of a special constable shows him as small in stature, with a fat stomach and spindly legs, and an eye-glass or spectacles, and in comparison to robust working-class males, specials are puny, and almost feminine (see figs. 2 and 3). For example, in the caricature by John Leech “Laying down the Law,” which appeared in Punch, a tiny special with an eye-glass around his neck, confronts a working-class man almost twice his height, and with arms thinker than the dandified special’s legs.[48] The special was rendered even more ridiculous by the batons or “staves” which were standard-issue weapons. In caricatures, these take on a phallic quality, simultaneously standing in for the special’s lack of masculine vigor and drawing attention to it.

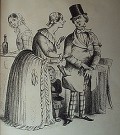

Most revealingly in relation to A Huguenot, in several images the feminine domestic sphere is shown as the key cause of the special’s failed masculinity. It is these images which prefigure most strongly Millais’s painting, both formally and thematically. I will discuss two examples in detail, turning firstly to the opening image from Six Scenes in the Life of James Green Esq., a Special Constable (fig. 2).[49]James Green appeared some time in 1848 and comprises six lithographed pages with an illustrated paper cover. It traces a day in the life of a special, covering his departure from the family home, his encounters with a group of small boys who pelt him with rubbish, and his coming upon several working-class figures too physically intimidating to be confronted. Green is last seen retreating to the domestic sphere, relating to his concerned wife and family, in order to explain his battered and filthy appearance, a dramatic but entirely fictional account of how he fought off a band of desperate Chartists. This series of caricatures may have been inspired by an incident reported in the Examiner and the Times in which the noted astronomer Sir James South attempted and failed to detain a nine-year-old boy for throwing stones at the Horse Guards after the child was rescued by his mother.[50]

James Green thus plays out the drama which later appeared in Millais’s A Huguenot: the tension between heterosexual and homosocial definitions of middle-class masculinity. One image in particular, which appears to have had a broader currency at the time, prefigures the composition of Millais’s painting. In the first scene titled “Mrs. G gives her husband a little advice, and a good deal of brandy” Green is shown parting from his wife. He stands next to the breakfast table, and despite the early hour the maid to the left carries a brandy-bottle and glass on a tray, indicating that, on his wife’s urging, Green has drunk some alcohol to fortify him and steady his nerves. Rather modishly dressed, and not very practically for a day that will be spent on the streets and potentially in physical confrontation with Chartists, Green pulls on his tight gloves for departure while screwing his face into an angry but comical grimace. Green’s legs are thin, but the straining buttons of his coat suggest a fat stomach beneath—a far from heroic physique. Around his arm is tied a white band, the required identifier of the special constable in 1848, and a clear visual parallel with the white scarf the woman is attempting to tie around her lover’s arm in A Huguenot. Green’s wife places a hand on her husband’s arm and urges caution in his dealings with the Chartists. Although not preventing him from leaving the house, her pleading, and even to some extent her stance, anticipates that of the woman in Millais’s painting. Significantly, the ideological tensions in play in this caricature are the same as in A Huguenot: Green must prove himself among men and through violence enacted in the public-sphere, but a woman, urging caution, pulls him back towards the safety of the feminine domestic sphere.

The threat to masculinity is further emphasized in the caption for this image, which gives the following dialog:

Mrs. G. – Now my love should you meet any of those deluded Chartists, pray be merciful, you do look so revengeful this morning.

Mr. G. – I know my duty as a man, and as a Special Constable, but you know what I am when I am up.

Mrs. G. – Yes my love that’s the very thing, and then you’ll be pulling out that horrid Truncheon of yours.[51]

The entendre-freighted text implies an erection, and the word “Truncheon,” underlined for emphasis, seems to refer to Green’s penis. The print which accompanies this text endorses this reading. The handle of Green’s baton projects stiffly from his pocket at waist level and points towards his wife. Between his two parents we see a small boy, who looks at the handle of the truncheon with wide-eyed shock and confusion in a humorous version of Freud’s primal scene.[52]

I will briefly examine a second caricature, this time from Punch (fig. 3), that also portrays a special taking leave of his wife, to demonstrate the prevalence of the tension between hetrosexual and homosocial spaces of masculinity at this time. In this image the conflict plays out at a front gate on a suburban street on the threshold between the domestic and the public sphere. A wife with a glass of brandy and hot water pursues her husband, followed by a maid, who like the servant in James Green holds a bottle. The husband, a special, holds a truncheon and wears a white band on his left arm. The wife pauses on the threshold of the domestic realm, while the husband turns back towards her and away from the street where several other male figures can be made out in the rain and gloom. The caption reads: “Special’s Wife: “Contrary to regulations indeed! Fiddlesticks! I must insist, Frederick, upon your taking this hot brandy-and-water. I shall be having you laid up next, and not fit for anything.’”[53] Here the hen-pecked husband is not allowed a word of protest. His wife has bundled him up so thoroughly against the damp night that he would be unable to swing his truncheon, or take an active part in defending the nation if it were required. His body is muffled and swaddled to such an extent that it is as if he is taking the comforts of the well upholstered Victorian interior out of the house with him, and is therefore doubly unable to escape the domestic sphere. The joke here is that, although unlikely to catch cold, Frederick is already “not fit for anything.” The same tension outlined previously is in play here. The conflict between the masculine public sphere, where a man must be fit to prove himself among men, and the domestic, feminine sphere that threatens to reduce and stifle that ability.

This theme was also explored by Millais in a print that shares similar compositional and stylistic elements (particularly with regard to shading) with the opening lithograph of James Green, and that was created at the same time he was working on A Huguenot. [54] In the frontispiece for the novel by Wilkie Collins, Mr Wray’s Cashbox (1852), Millais shows the novel’s heroine, Annie Wray, tying the cravat of the novel’s awkward but honest hero, Martin Blunt, in a domestic interior.[55] Here the rather clumsy male figure is depicted as dependent on a woman’s help to secure a proper appearance before entering the public sphere. This is both literally, in terms of binding or tying with cloth, and figuratively, in terms power relations between genders, the kind of assistance that the Huguenot is refusing by asserting his power to choose in Millais’s contemporary project in paint.[56]

Millais’s A Huguenot reenacted, but also submerged, some of the trauma of 1848 when middle-class masculinity was exposed as falling short of heroic ideals: weak in the face of working-class bodies developed by hard labor, and having been feminized by the comforts of the domestic sphere and sedentary employment. These perceived failings subsequently haunted readings of the painting in the context of the Papal Aggression outcry. Many elements from caricatures dealing with the special constable reappear in A Huguenot, but by depicting the moment immediately before he must choose between the contradictory modes of heterosexual and homosocial masculine life, between the dual threats of feminizing domesticity and violent death at the hands of other men, Millais allows crisis to be postponed.

Conclusion

Considered in the broader context of Millais’s career, this reading of A Huguenot suggests new approaches to the artist’s romantic genre paintings. The ubiquity of A Huguenot in print form in Victorian homes[57] is testimony to the resonance the image found within the middle-class paternalistic family unit, most immediately as a homage to the “sweetness of woman,”[58] but additionally as a cipher for the complicated nature of middle-class masculinity. In this regard, the current reading of A Huguenot can be seen as a broadening of Danahay’s analysis of other Pre-Raphaelite texts and images as sites where the illicit narcissistic desire of males to see themselves represented leads to the projection of masculine concerns onto subjects depicting femininity; in Danahay’s formulation: “self-involved desire must be expressed through a swerve into the feminine,” in this case the romance of sentimental genre painting.[59] We might note here how the couple in Millais’s painting are mirror images of one another, locked eye to eye, waist to waist and toe to toe, the conceptual intertwining of masculine identity with the representation of the feminine emerges in the figures’ tortured embrace, just as the painting itself becomes a mirror for anxious masculine reflection. This analysis helps in understanding the significance of F. G. Stephens’s preoccupation with the reaction of male viewers to the painting at the 1852 Royal Academy, where prolonged, repeated, and shared experience of the work revealed it as a manifestation of “the old feelings of men in a new garment”: the “old feelings” being the relatively recent threats to middle-class masculinity posed by the separation of spheres and by the class tensions resulting from industrialization, and the “new garment” being Millais’s commercially successful tragic-romantic genre painting. [60] This reading helps to explain the significance of this work for Victorian audiences, and how it was able to cement the artist’s reputation and set the precedent for Millais’s artistic production in the decades that followed.

This article was written while I was a Research Fellow at Wolfson College, Oxford. I would like to thank the audience of the Ashmolean Research Seminar for their helpful comments on an early version of this paper.

[1] J. G. Millais, The Life and Letters of Sir John Everett Millais, President of the Royal Academy, by his Son John Guille Millais (1899; London: Methuen and Co., 1905) 1:146. The abbreviation “R. A.” refers to the Royal Academy.

[2] For example, in the catalogue for the Millais exhibition held at Tate Britain in 2007: Jason Rosenfeld and Alison Smith, with contributions by Heather Birchall, Millais (London: Tate Publishing, 2007), Ophelia closes the section “Pre-Raphaelitism,” 68–69, while A Huguenot can be found in the section “Romance and Modern Genre,” 94–95. For contextualisations of A Huguenot in print form see Laurel Bradley, ““Millais, Our Popular Painter,’” in John Everett Millais Beyond the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, ed. Debra N. Mancoff (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001), 181–205, esp. 184; and Malcolm Warner, “Millais in Reproduction,” in Writing the Pre-Raphaelites: Text, Context, Subtext, ed. Michaela Giebelhausen and Tim Barringer (Farnham, Surrey and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009), 215–36.

[3] The dealer David Thomas White, who purchased the painting for £250 before it was submitted to the Royal Academy, gave the artist a further £50 after the mezzotint by Thomas Oldham Barlow was published in 1856.

[4] See catalogue entry 107, Rosenfeld and Smith, Millais, 184; and Laurel Bradley, “Millais’s Bubbles and the Problem of Artistic Advertising,” in Susan P. Casteras and Alice Craig Faxon, Pre-Raphaelite Art in its European Context (Madison, Teaneck and London: Associated University Presses, 1995), 193–209.

[5] See Leonore Davidoff and Catherine Hall, Family Fortunes: Men and Women of the English Middle Class, 1780–1850 (London, Melbourne, Sydney: Hutchinson, 1987); John Tosh, A Man’s Place: Masculinity and the Middle-Class Home in Victorian England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999); Herbert Sussman, Victorian Masculinities: Manhood and Masculine Poetics in Early Victorian Literature and Art (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Martin A. Danahay, A Community of One: Masculine Autobiography and Autonomy in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993); Martin A. Danahay, Gender at Work in Victorian Culture: Literature, Art and Masculinity (Aldershot, Hants, and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2005); and James Eli Adams, Dandies and Desert Saints: Styles of Victorian Masculinity (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995). See also Michael Roper and John Tosh, eds., Manful Assertions: Masculinities in Britain since 1800 (London and New York: Routledge, 1991).

[6] For a discussion of the mirroring of masculine anxieties in Pre-Raphaelite painting see Martin A. Danahay, “Mirrors of Masculine Desire: Narcissus and Pygmalion in Victorian Representations,” Victorian Poetry 32, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 35–54.

[7] According to Tate Britain’s web site, accessed July 25, 2012, http://www2.tate.org.uk/ophelia/subject.htm, Ophelia is the most popular postcard sold in the gallery shop.

[8] William Holman Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood; with 40 photogravure plates, and other illustrations, 2nd rev. ed. (London: Macmillan, 1913), 1:202.

[9] Susan P. Casteras, “John Everett Millais’s “Secret-Looking Garden Wall’ and the Courtship Barrier in Victorian Art,” Browning Institute Studies,13 (1985): 71–98; and Paul Barlow, Time Present and Time Past: The Art of John Everett Millais (Aldershot, Hants, and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2005).

[10] Casteras writes “The Huguenot . . . challenged these preconceptions about dull courtship images by infusing new lifeblood, a powerful amalgam of love and danger, and startling symbolic realism into the otherwise dross sentimentality of this subject in the 1840s and 50s.” Casteras, “John Everett Millais’s “Secret-Looking Garden Wall.’” 74.

[11] Barlow, Time Present and Time Past, 39–42.

[12] Ibid., 92.

[13] Ibid., 42.

[14] The quotation from Caldwell reads: ““When the clock of the Palais de Justice shall sound upon the great bell, at daybreak, then each good Catholic must bind a strip of white linen round his arm, and place a fair white cross in his cap.’ – The order of the Duke of Guise.” Anne Marsh-Caldwell, The Protestant Reformation in France, or, the History of the Hugonots, by the author of “Father Darcy,” “Emilia Wyndham,” “Old Men’s Tales,” etc. (London: Richard Bentley, 1847), 2:352.

[15] The reviewer for the New Monthly Magazine erroneously gave the painting the title “A Catholic Lady tying on the Scarf of her Huguenot Lover.” For other reviews which identify the woman as Catholic see “A Glimpse of the Exhibition at the Royal Academy,” New Monthly Magazine and Humorist, May 1852, 123; “Royal Academy,” Athenaeum, no. 1282, May 22, 1852, 581; [Tom Taylor], ““Our Critic’ Among the Pictures,” Punch, May 22, 1852, 216. Unusually, the reviewer for the Morning Chronicle identified the woman as a Huguenot, see “Royal Academy: Third Notice,” Morning Chronicle, May 17, 1852,5. The woman wears a ring on the ring-figure of her right hand that could be a sign that the couple is engaged. The ring takes the form of a knot, echoing the knot in the scarf being tied around the man’s arm. Millais identifies the woman as Catholic in a letter to Mrs. Combe dated November 22, 1851. See Millais, Life and Letters, 1:135.

[16] For critics who suggest that the man will refuse the badge and be killed, see “Royal Academy: Third Notice,” 5; “Art and the Royal Academy,” Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, August 1852, 235; “Exhibition of the Royal Academy,” Illustrated London News, May 8, 1852, 368; “The Royal Academy Exhibition,” The Era, May 9, 1852, 9; and [William Michael Rossetti], “The Royal Academy: Subjects of Invention,” Spectator, May 15, 1853, 471. For the suggestion that Millais intended this outcome, see his letter to Mrs. Combe, November 22, 1851, quoted in Millais, Life and Letters, 1:135. In contrast Tom Taylor wrote “The moment is rightly chosen, when nothing is decided—when two fates hang trembling in the balance, and the spectator finds himself assisting in the struggle, of which he may prophesy an issue, as his sympathy with the love of the woman or the strength of the man happens to be strongest.” ““Our Critic’ Among the Pictures,” 216.

[17] Millais, Life and Letters, 1:147.

[18] Ibid., 1:148. Of this series J. G. Millais names The Proscribed Royalist and The Black Brunswicker; the fourth picture is The Order of Release, 1746.

[19] J. G. Millais’s opinion has also been echoed in criticism down to the present. The catalogue entry on A Huguenot that accompanied its exhibition at Tate Britain in 2007 states: ““A Huguenot’ was the first of a series of highly successful paintings that focus on the constraints placed on lovers in situations of civil conflict.” Rosenfeld and Smith, Millais, 94.

[20] “The Exhibition of the Royal Academy,” Art Journal, June 1852, 173; “Exhibition of the Royal Academy (Second Notice),” Times, May 14, 1852, 6; “Art and the Royal Academy,” 235; “The Royal Academy: Subjects of Invention,” 471. See also “Royal Academy Third Notice,” 5, which uses the word “firmness” twice in one sentence.

[21] “Exhibition of the Royal Academy,” 173. “Exhibition of the Royal Academy (Second Notice),” 6. “Royal Academy,” 581.

[22] This power makes her phallic at the same time that she represents the threat of the Other; one critic invoked this duality, referring to “The female head . . . with her cleft lips.” “Art and the Royal Academy,” 235.

[23] Sussman, Victorian Masculinities, 5.

[24] Tosh, A Man’s Place, 112.

[25] “Royal Academy,” 581.

[26] See Millais, Life and Letters, 1:138 and 141. For the reference to Chambers’s Journal see Malcolm Warner, catalogue entry 41 in Leslie Parris, ed., The Pre-Raphaelites (London: Tate Gallery Publication, 1984), 99.

[27] A series of preparatory sketches made for the painting show that, questions of inspiration aside, the figural composition of A Huguenot was not simply lifted from either the opera or an alternative source, but was worked out by the artist through experimentation.

[28] See Parris, Pre-Raphaelites, 99; and Malcolm Warner, The Drawings of John Everett Millais, Catalogue of an Exhibition held at the Bolton Museum and Art Gallery (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1979), 29. The libretto includes the lines sung by the heroine Valentina to the hero Raul in act V, scene II: “Yes, with this scarf round thy arm entwining, thou mayst in safety gain at once the Louvre, there with the Queen’s assistance made already secure your life is safe.” Giacomo Meyerbeer, Les Huguenots, trans. Frank Romer, “Royal Edition” for voice and piano (London: Boosey and Co., 1870), 460.

[29] See Meyerbeer, Les Huguenots, 460.

[30] In addition Millais’s own wish to downplay the plot of Les Huguenots may have had a personal motive. In 1851while working on A Huguenot Millais informed Mrs. Combe that there was a rumor circulating that he was Catholic, and confessed that he feared that “they [Catholics] will turn the subject I am at present about to their advantage.” Millais, Life and Letters, 1:135.

[31] For details see Saho Matsumoto-Best, Britain and the Papacy in the Age of Revolution, 1846–1851 (Woodbridge, Suffolk, and Rochester, NY: The Boydell Press, 2003), 145.

[32] Ibid., 147–49.

[33] Ibid., 154 and 157.

[34] I have been able to locate only one review, from the periodical the Era, which seems to refer to Papal Aggression. It reads: “It is sad to think that such men [as the Huguenot] died in vain for their country, that even now their memory is, comparatively, little revered in France, and, perhaps still sadder, that there are men in England so base, or so forgetful of the past, as to desire the re-establishment of that priesthood who were guilty of their slaughter.” “The Royal Academy Exhibition,” 9.

[35] See Susan P. Casteras, “Virgin Vows: The Early Victorian Artists’ Portrayal of Nuns and Novices,” Victorian Studies 24, no. 2 (Winter, 1981): 157–84, esp. 162.

[36] See Nancy Lusignan Schultz, introduction to Veil of Fear: Nineteenth-Century Convent Tales by Rebecca Reed and Maria Monk, ed. Nancy Lusignan Schultz (West Lafayette, IN: NotaBell Books, 1999), vii.

[37] See for example Maria Monk,The Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk: Being, a Narrative of her Sufferings . . . to which is added Notes, Affidavits, Confirmations and Facts of the Present Day (London: Houlston and Stoneman, 1851); and Maria Monk, Awful Disclosures of Maria Monk, of the Hotel Dieu Nunnery of Montreal, with an Appendix; and a Supplement (London: James S. Hodson, 1851).

[38] Monk’s narrative was likely directed and augmented by a number of Protestant men, including the Reverend J. J. Slocum.

[39] See Schultz, Veil of Fear, xvi. For the description of the murder of one of the nuns see 59–65.

[40] See ibid., 16, 63, 106, 107, 109, 115, and 122–23.

[41] Tosh writes, “As a social identity masculinity is constructed in three arenas - home, work and all-male association. Not only is the balance between them historically variable; analysing the connections between them soon reveals how each impinges on the other.” Tosh, A Man’s Place, 2.

[42] Tosh, AMan’s Place, 6. Tosh sees the “heyday” of Victorian domesticity as lasting from the 1830s to the 1860s, which he describes as “for the most part a period of peace, when the country was untroubled by external threat.” The year 1848 stands as an exception to this, where threat, from the Chartists, was internal to Britain. The images of special constables produced in this year suggests that the tensions that Tosh describes as coming to a head in the last three decades of the nineteenth century also surfaced at much earlier periods in times of stress.

[43] See John Saville, 1848: The British State and the Chartists Movement (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987) and David Goodway, London Chartism, 1838–1848 (Cambridge, New York, London: Cambridge University Press, 1982), for these figures see 130.

[44] Goodway writes “The significance of this enrolment [of special constables] . . . lies in its decisive indication that the middle classes were now prepared to ally themselves unreservedly with the ruling class against the threat of proletarian revolt.” Goodway, London Chartism, 74. Saville comments “The outstanding feature of 1848 was the mass response to the call for special constables to assist the professional forces of state security. This was the significance of 1848: the closing of ranks among all those with a property stake in the country, however small that stake was.” John Saville, 1848: The British State and the Chartists Movement (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 227.

[45] See Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 1:101–2. They witnessed a clash between “roughs” and the police near Bankside. Hunt recalled, “We felt the temptation to see the issue, and Millais would scarcely resist pressing forward, but I knew how in a moment all present might be involved in a fatal penalty. I had promised to keep him out of wanton danger, but it was not without urgent persuasion that I could get him away.” Ibid., 1:102.

[46] See Saville, 1848, chapters 5 and 6, “Summer” and “Days of Judgement.”

[47] “Olympic,” Theatrical Times, No. 106 (Saturday, May 13, 1848), 157.

[48] Anonymous wood-engraver, drawn by John Leech, “Laying Down the Law,” Punch, April 22, 1848, 172. For another example of how the special’s body fell short of the masculine ideal in a number of different ways see the lithographed cover by Madeley to The Special Constables, Comic Song, sung with unbounded applause by Mr. J.W. Sharp at the Royal Gardens Vauxhall (London: T.E. Purday, n.d. [1848]).

[49] John Richard Jobbins, Six Scenes in the Life of James Green Esq., a Special Constable. Sketched by a Special (London: Bogue, 1848). The name Green is a joke in itself. Green suggests someone untried and juvenile. It also has connotations of femininity, since green could also be used to refer to anemic girls, and connoted virginity.

[50] “Requital of Special Service,” Examiner, June 24, 1848, 403; and “Police: Hammersmith,” Times, June 21, 1848, 7.

[51] Jobbins, James Green, 1. Original emphasis.

[52] Similar themes are raised in an anonymous wood-engraving, drawn by John Leech, captioned “Special Constable Preparing for the Worst. – Drying his Gunpowder in the Frying-Pan,” Punch, April 22, 1848, 14,170. Here a special bends over the kitchen stove at his task, a truncheon sticking out of his back-pocket like a tail. His wife looks on perplexed, while two children fight over a rolling-pin in the foreground.

[53] Anonymous wood-engraver, perhaps drawn by John Leech, “Special’s Wife . . . ,”Punch, April 22, 1848, 166.

[54] Millais, Life and Letters, 1:151.

[55] See Susan P. Casteras, Pocket Cathedrals: Pre-Raphaelite Book Illustration (New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, 1991), 20, fig. 5. The incident illustrated occurs in chapter 3.

[56] I would like to thank the anonymous reader of this paper for pointing me to this illustration.

[57] J. G. Millais wrote in ca. 1899 that Ophelia and A Huguenot were “familiar in every English home.” Millais, Life and Letters, 1:115.

[58] Ibid., 1:148.

[59] Danahay, “Mirrors of Masculine Desire,” 35.

[60] F. G. Stephens, quoted in Millais, Life and Letters, 1:146.