The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

De Delacroix à Kandinsky: L'Orientalisme en Europe

Van Delacroix tot Kandinsky: Oriëntalisme in Europa

Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique / Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, Brussels

October 15, 2010 – January 9, 2011

Orientalismus in Europa: Von Delacroix bis Kandinsky

Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung, Munich

January 28 – May 1, 2011

L'Orientalisme en Europe: De Delacroix à Matisse

Centre de la Vieille Charité, Marseille

May 27 – August 28, 2011

Catalogue

De Delacroix à Kandinsky: L'Orientalisme en Europe.

Roger Diederen and Davy Depelchin, eds. Essays by Roger Benjamin, Depelchin, Diederen, Luc Georget, Jan de Hond, Robert Irwin, Peter Benson Miller, Christine Peltre, Eugène Warmenbol.

Paris: Hazan, 2010.

312 pp.; 238 color illustrations, 14 b/w; chronology, bibliography, checklist of exhibited works (with page references).

ISBN: 978-2-7541-0506-4 (French)

Van Delacroix tot Kandinsky: Oriëntalisme in Europa

ISBN: 978-2-7541-0520-0 (Dutch)

Orientalismus in Europa: Von Delacroix bis Kandinsky.

Munich: Hirmer, 2010.

ISBN: 978-3-7774-3251-9 (German)

€39,90

Parenthetical page numbers refer to the German edition of the catalogue. Links in the text below will launch in a new window.

Edward W. Said remarked in the first paragraph of his hegemonic book of 1978 that "the Orient was almost a European invention."[1] Appropriately, the de facto capital of the European Union hosted in October 2010 the first international exhibition on the Continent in more than two decades to document the vision in European painting and sculpture of what was once called the Orient (fig. 1). Designed for audiences presumed to be unfamiliar with most of the artists associated with the label Orientalism or with the controversies that had made the term a pejorative for the past three decades, the exhibition assembled a characteristic sample within the two chosen media. Treading lightly through the long nineteenth century, it skirted – yet did not deliberately mask – the minefields of post-colonial theory. Among the aptly chosen works French and English names predominated, yet Austrian, Belgian, Czech, Dutch, Danish, German, Italian, Ottoman, Spanish, Swiss, and Russian artists represented peripheral streams of imagery channeled for this show.

In multicultural Brussels, the entry queue passed three large screens sharing responses to the works from people with a migration background; the museum education department meant to encourage "a better understanding of the other." A man from Burkina Faso, for example, wondered why a veiled oriental woman is seen as exotic while a woman wearing a veil in the West poses a problem. Publicity for the exhibition, not surprisingly, showcased the unveiled. A headline in one Flemish newspaper – "When Islam was still a fairy tale" (De Standaard, November 15, 2010 [.pdf]) – hinted at a fusion of allure and threat that the topic continues to evoke in contemporary Europe. At the second venue, the Kunsthalle of the Hypo-Kulturstiftung above a shopping mall in central Munich, the opening wall text promised a history of conflicts and projections, noting that "our original fascination with these foreign cultures is sadly lacking in the discussions on burkas and minarets." Shortly before the exhibition opened in Munich in January 2011, Tunisia overthrew its regime and protesters occupied Tahrir Square in Cairo. A winter journey past some 150 nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European images, chiefly of North Africa and the Middle East, took on new relevance. In the exhibition foyer visitors could orient themselves, so to speak, at a map pinpointing sites mentioned in the show (fig. 2).

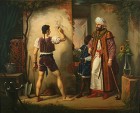

Although installation and, to some extent, content differed at each venue, the catalogue checklist indicates that 107 works were scheduled for all three cities on the tour.[2] Titles of exhibition sections corresponded in most cases to those of catalogue essays by the editors, Roger Diederen and Davy Depelchin, and a team of seven contributors. In both Brussels and Munich a painting by Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret introduced the theme: Europeans looking at Orientals. First seen at the Paris Salon of 1819, the picture shows the fifteenth-century Florentine painter Filippo Lippi in chains after his kidnapping by pirates; he draws on a wall the image of his master in Algiers (figs. 3, 4). According to a tale published by Giorgio Vasari in 1550, the seemingly miraculous likeness won the artist his freedom after eighteen months of captivity.[3] In an astute catalogue essay – "Crossing Borders" – the Munich curator Diederen points out that Bergeret perpetuated not only the Lippi legend, but Vasari's mistaken belief that accurate portraiture was unknown in the Islamic tradition (41–44, 277n6).

Another crosser of borders in the first room in Munich was the Ottoman painter and museum director Osman Hamdi Bey, who abandoned law school in Paris to study under the artist Gustave Boulanger (fig. 5). Osman Hamdi showed his droll Carpet Dealers, a European family exchanging wary looks with indigenous merchants, at the Berlin Academy in 1888; the Nationalgalerie in Berlin immediately acquired his canvas depicting the ambivalent attraction and distrust recorded in many a travel account (45–47).[4] Linking doomed political entities – the German Empire would end in 1918 and the Ottoman Empire in 1923 – the painting is a beguiling prelude to the confrontation traced in subsequent rooms. For the catalogue, a detail from Osman Hamdi's painting serves as frontispiece to a concise historical introduction by the Brussels curator Depelchin. Here, as well as in an illustrated chronology of Orientalism from 1798 to 1914, Depelchin provides a context for the popular artistic trend, demonstrating its complexity beyond the corsairs and concubines imagined by Victor Hugo; a passage from Hugo's preface to Les Orientales (1829) opens his essay.

The timeline of the exhibition narrative began in the second section: "Egyptomania." On August 1, 1798, one month after Napoleon and his army had disembarked near Alexandria to conquer Egypt, the English admiral Horatio Nelson surprised and decimated the French fleet at anchor in Abukir Bay. During a fierce night battle, Napoleon's flagship L'Orient caught fire, exploded, and sank. When Napoleon learned that his army was stranded in Africa, he immediately shifted the blame to the vice-admiral who had died on board his ship. Thanks to the young general's gift for spin and to a team of civilian specialists – the savants – embedded in his ill-fated military expedition, Bonaparte's ephemeral conquest of Egypt came to be seen as a triumph.[5] Among the savants was Dominique Vivant Denon, soon to become director of Napoleon's Louvre. Denon had seen the naval battle through a telescope from a tower on land and had heard L'Orient explode. Even before the debris from the Battle of the Nile washed ashore, the tireless draftsman, then over fifty years old, resumed his continual sketching of the African adventure. His energy gave the first strong impulse to nineteenth-century Orientalism.

Denon's journal of the campaign published in 1802 became an international bestseller and its 141 etched plates a source for views of Egypt for the rest of the century.[6] In the Brussels installation, an excerpt from Denon's dedication of his book to Napoleon was mounted next to a painting first seen in the Salon of 1812 (fig. 6). Seemingly pure propaganda, the picture by Jean Charles Tardieu of French troops enjoying rest and recreation at Aswan (Greek Syene) combines two scenes in Denon's eye-witness account of his travels in Upper Egypt. Denon described a milestone set up at Syène by weary light infantrymen to mark the distance to Paris, then in the next paragraph discusses a ruined temple.[7] Tardieu placed the ruin in the center of his composition with a soldier writing "Route de Paris à Syène" on the ancient stone. The exhibition also featured a second crucial publication of the work of the savants: Description de l'Egypte (1809–30). With some 900 engraved plates – a few hand colored – the volumes continued to appear after Napoleon's exile and death; two examples were on display in Brussels (fig. 7).[8] Interest in Egypt swelled when a new edition began in 1821, the year before Jean-François Champollion published the first translation of the hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone, the key find of the expedition.[9]

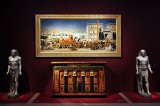

Furniture made to house the bulky volumes of the Description forms a study in itself, and one of these masterpieces of cabinet work, a miniature version of the Hathor temple in Dendera, was a highlight of the Munich installation (fig. 8).[10] There the exhibition attained a moment of rhetorical perfection, with nearly identical marble statues (lent by the Musée Marmottan-Monet, Paris) flanking the commode. Similar figures of Antinous as Osiris, inspired by those found during the eighteenth century in Hadrian's villa at Tivoli, became a staple of Egyptomania, cropping up everywhere from the Ostankino Palace in Moscow to Buscot Park in Oxfordshire.[11] On the wall above the commode hung Edward Poynter's Israel in Egypt, a title taken from Handel's oratorio of 1739. In this exemplar of biblical Orientalism, Poynter shows the captive Israelites hauling a pair of Nubian lions – based on the two displayed in the British Museum since 1835 – towards the pylon gateway of the temple at Edfu. The backdrop includes the Great Pyramid of Giza, the temple at Philae, and the obelisk at Heliopolis. Poynter sold his slave picture in 1867 to John Hawkshaw, an eminent railway engineer. Hawkshaw had produced a feasibility study for the Suez Canal in 1863 that convinced the wavering Isma'il Pasha to proceed with the project in the face of British opposition based on accusations of forced labor.[12] Next to Poynter's spectacular Old Testament set piece in Munich hung a single, grave ruin by his teacher Charles Gleyre, The Ramesseum (1840, Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne). The small Gleyre work held its own, even with two dying Cleopatras in the room, plus a lovely fragment of a third by Théodore Chassériau.[13] Belgian archaeologist Eugène Warmenbol of the Université Libre de Bruxelles ranges gracefully in his catalogue essay for this section from Bonaparte to the Antwerp Zoo and its Egyptian temple (1856) (55–71).

In an adjacent gallery the viewer encountered the first of ten works in the exhibition by Jean-Léon Gérôme, who had also studied under Gleyre: a bronze and ivory Veiled Woman (fig. 9). Objects assembled in Brussels under the rubric "Beyond the Grand Tour" were labeled in Munich "'Rome is no longer in Rome'" (figs. 10, 11). This much-cited quotation is from a letter of 1832 written by Eugène Delacroix to the critic Auguste Jal at the end of the artist's five-month trip to Morocco on an official diplomatic mission with Charles Edgar Comte de Mornay.[14] Delacroix proposed that it would be better to send young painters in search of classical figures to Africa, rather than to the French Academy in Rome. The feeling, shared by other artists and travel writers, that they were seeing a lost classical world in the modern Orient is persuasively evoked in this section of the show. In his catalogue essay, Diederen examines both the discovery of living antiquity by Delacroix and the charm of its ruins for other painters (72–85). In another essay, Christine Peltre, art historian at the Université Marc Bloch, Strasbourg, portrays the dedicated professionals recording impressions in a harsh environment, suitcases packed with fragile sketchbooks, portfolios, albums, and notes, masterful works drawn "on the pommel of a saddle" (89).[15] The generous gallery space in Munich permitted a vicarious voyage from Roman Baalbek to Moorish Spain, gateway for many artists – David Roberts, Achille Zo, Georges Clairin, Henri Regnault, and Wilhelm Gentz, for example – to further ventures. The literary context of "The Orient within Europe" is traced in the catalogue by Robert Irwin, historian, novelist, and expert on the Alhambra and Arabic literature. Following the Moorish canvases was a colorful array of paintings by an early generation of traveling romantics: Delacroix, Alexandre Decamps, Chassériau, Prosper Marilhat, and Horace Vernet (figs. 12, 13).

The visitor in Munich then entered a stunning room dedicated to the Abrahamic religions. On walls painted a deep aubergine, Gérôme's Golgotha (Consummatum Est!) opened a series of ten pictures selected to represent Judaism and Islam, as well as Christianity (fig. 14).[16] Next to Golgotha hung one of several versions of the preternatural Rest on the Flight into Egypt by Luc-Olivier Merson.[17] Dominating the apse-like end of the long gallery was The First Mass in Kabylia (1854, Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne), a late work by Horace Vernet (fig. 15). The picture, dating from the early years of the Second Empire, is a benediction and farewell after Vernet's two decades as a painter of the brutal French conquest of Algeria.[18] On his last trip to Africa, the artist met the founding abbot of the Trappist monastery at Staouëli, Dom François-Régis de Martrin-Donos; Vernet made a spiritual retreat and took Easter communion at the abbey in late March 1853. He then persuaded the Protestant governor general of Algeria, Jacques-Louis Randon, to invite the monk to join a military expedition in the Babors range of the Atlas Mountains. By early June, when Vernet and the somewhat hesitant Trappist reached the two army divisions camped near the mouth of the Oued Agrioun, most of the tribes along the river had submitted to the French. The governor organized a ceremony of investiture on June 5, bestowing on some forty sheiks a red burnoose as a symbol of their office; the abbot then celebrated Mass under a cross of cork oak branches. Vernet – colonial landowner, lifelong paramilitary, and converted freethinker – was stirred, not by a battle, but by army bands and Catholic rites amid cannons and drum rolls in this bivouac near the coast of Kabylia. Jan de Hond of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, who wrote the catalogue essay on the religious works, wisely refers the reader to a superb description of the Vernet painting by Peter Benson Miller.[19]

The same week in early June 1853 that Vernet spent in Kabylia, Eugène Fromentin was on the other side of the Atlas Mountains in the Sahara. A painter who not only traveled but wrote books that still sell briskly today, Fromentin arrived in Laghouat six months after the French had ended a siege and massacred much of the population; the large, sad town still smelled of death, he wrote. As it was for Vernet, this would be Fromentin's last visit to Algeria. Among the works in his studio when he died in 1876 was a desert version of Théodore Géricault's Raft of the Medusa (1819, Musée du Louvre): The Land of Thirst (undated, Musée d’Orsay, Paris). On tour in the recent show was what appears to be a second version (ca. 1869, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels), in which the artist omitted the hopefully raised arm and added a dead horse.[20] A catalogue essay by Luc Georget, curator at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Marseille, borrowed Fromentin's title, "The Land of Thirst," also the section label for an effective display in both Brussels and Munich (184–201).[21] A striking canvas in this section by Maurice Bompard, A Street in the Chetma Oasis, merits study as a mutation in the Orientalist genome (fig. 16). In a small painting on panel, Bompard had emulated the sun-parched main street in Laghouat, a successful Fromentin picture of 1859; returning to the Arab street motif in 1890, Bompard moved it to the oasis near Biskra, distinguishing the figures and bleaching the shadows.[22]

After dusty towns built for shade and vast stretches of sand, the exhibition offered escape into the intimacy of harems and hammams. The works dealing with women – paradoxically the most typical of Orientalist subjects, yet the least likely to be based on observation – were accorded in both venues something of a chambre séparée. The section label in Brussels was "Hedonistic Dreams." In Munich the smoke-filled room labeled "Of Hashish and Hallucinations" was painted blue to match the robe in Fabbio Fabbi's Dream, the pillow in Achille Zo's The Dream of a Believer, or the tiled wall behind The White Slave by Jean Lecomte du Nouÿ (fig. 17). Diederen's catalogue essay elucidates A Eunuch's Dream – also by Lecomte du Nouÿ, a Gleyre student – and its literary source, Lettres persanes by Charles Montesquieu (166–83). In a second catalogue essay for this section – "And the Women?" – Christine Peltre gives a number of pertinent answers to what Théophile Gautier called the first question posed to someone returning from a trip to the Orient. The essays acknowledge post-Saidian controversies around depictions of odalisques and indolence; the authors seem, however, to invite a light-hearted approach, signaled by the installation of Charles Cordier's marble bust of a singing Algerian Moorish woman amid the steamy fantasies in the ladies' quarters.

Cordier is the ruling mufti of the following section, designated in Brussels "In the Name of Learning." A trenchant catalogue essay by Peter Benson Miller ("Scientific Orientalism? Ethnography, Anthropology, and Slavery") locates the sculptor's work outside the Salon and the art market, tracing the connection with early anthropological studies. In Munich, the installation featured an anonymous life cast of a Sudanese former slave, Seïd Enkess, produced in 1847 for the Society of Ethnology of Paris; Enkess was working as a model for François Rude, Cordier's teacher (fig. 18).[23] The Sudanese model posed for Cordier in 1848 – the year that France abolished slavery – and the resulting bronze bust Saïd Abdallah and its pendant of 1851, African Venus, were purchased from the 1851 Great Exhibition in London by Queen Victoria as a birthday gift for her husband (fig. 19).[24] After his first trip to Algeria in 1856, Cordier showed twelve busts in the Salon of 1857 as a "gallery of Algerian types." Seven busts were bronzes, three were in marble (including the Singing Moorish Woman), and two combined metal with stone. The beautiful bronze and onyx Negro of the Sudan from the Salon is in the Musée d’Orsay, and a delectable bronze reduction with silvered costume elements from the Dahesh Museum of Art was shown in all three venues of the tour. Two objects demonstrated the French perception of a favored Algerian "type": Cordier's Kabyle of Badjara and the oil study by Isidore Pils entitled Head of a Kabyle. The head was made by Pils as preparation for a major commission, a painting commemorating festivities honoring Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie during their first Algerian tour in September 1860.[25]

Two loans from the Dahesh Museum of Art anchor the paintings aptly grouped in Munich as "Human Trafficking": Raid of Bashi-bazouks in a Christian Village in Herzegovina (1861) by Jaroslav Čermák and the masterwork by Gustav Bauernfeind, Jaffa, Recruiting of Turkish Soldiers in Palestine (1888). Čermák's picture won a medal at the Salon of 1861, and although some critics scoffed at the crowds it drew, Gautier praised the luxuriant female figure (fig. 20). The series of abductions and impressments ended with Gérôme's Egyptian Recruits Crossing the Desert (1857).[26] Next to the Gérôme picture in Munich and almost forming a category of its own – "Colonialism" – was Entry of Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia in Jerusalem, 1869, commissioned from Wilhelm Gentz in 1872 (fig. 21). King Wilhelm I sent his son to represent Prussia at the opening of the Suez Canal, and en route the crown prince stopped in Jerusalem, making an official entry through the Damascus Gate. Friedrich Wilhelm then accepted a gift from the Sultan to his father, the historic plot in the Muristan quarter on which the neo-Romanesque Church of the Redeemer would be built in the 1890s. Germany had become an empire by the time Gentz traveled to Jerusalem in 1873 to document the site; adapting Palm Sunday iconography, he placed the Hohenzollern prince in the center on a white stallion and inserted himself in the right foreground on a donkey, sketching the event as if he had been there (144–52).

Rather than establish a colony in the eastern Mediterranean, the Germans would negotiate a concession to build the Baghdad Railway. The Gentz canvas – as much as any Horace Vernet battle – emitted a whiff of colonial aspirations, but the penultimate section of the exhibition ("Genre") was an oasis innocent of imperial schemes or demeaning subject matter (fig. 22). With appealing glimpses of everyday life, the Munich installation assembled quiet but enthusiastic transactions – often in cafés, markets, or street-front shops – between artists and various exotic cultures. A courtyard in Cairo was painted with affection by Willem de Famars Testas, chronicler of Gérôme's fourth voyage to the Orient in 1868 (37–43).[27] On this trip with Testas and Gérôme, Léon Bonnat would have seen his magnificent Barber of Suez exhibited some years later in the Salon of 1876 (fig. 23). Weavers of Bou Saâda, one of the last works by Gustave Guillaumet, typifies his quest for the Algerian light; the painting was accompanied in the exhibition by a version of the bronze monument his friend Louis Ernest Barrias made in 1890 for the painter's tomb in Montmartre Cemetery (figs. 23, 24). The final painting in the room was Falcon Hunting in Algeria, la Curée by Fromentin. When it was shown at the Salon of 1863, Jules-Antoine Castagnary – a critic who gave the name Orientalism to an artistic tendency he disdained – mentioned only a smaller painting, Arab Falconer (Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk). Still, he conferred on Fromentin his highest praise: the painter-writer had arrived at pure naturalism. Another painting in this group in Munich won a dispensation from Castagnary at the Salon of 1870: Alberto Pasini's "lovely gray landscape," Doorway of the New Mosque (Yeni Çami) in Constantinople (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nantes). The critic admitted that looking at the Pasini picture, he forgot his long-time hatred of Orientalism. This roomful of likable works was a boon as the exhibition path approached its end.

The final room soared into modernity with Orange Market at Blidah by Henri Evenepoel, who died in the last week of the nineteenth century (fig. 25). The young Belgian traveled to Algeria in October 1897 for his health, taking a small Kodak camera. His photographic album at the Musée d’Orsay, assembled by his father after the painter's death, includes no snapshots of the Blidah markets, but many of a market at Biskra. Roger Benjamin, art historian at the University of Sydney, entitles his catalogue essay for this section "Journey to the East" in honor of Hermann Hesse's 1932 novella, Die Morgenlandfahrt (202– 225). Benjamin illustrates a street view taken by Evenepoel of his father in Biskra and gives a lively account of Paul Klee's brief trip to Tunisia in April 1914 with his friends August Macke and Louis Moilliet. Macke painted the oils in the exhibition shortly before he fell in battle during the second month of World War I.

Also hanging in this last room was an important picture by yet another Gleyre student: Pierre-Auguste Renoir (fig. 26). Benjamin discusses in his catalogue essay various works related to Renoir's two trips to Algeria, as well as his one painting in the show, Arab Festival (1881, Musée d’Orsay, Paris).[28] The exhibition title promised a Wassily Kandinsky and a different work was shown in each city; in Munich his Arab Cemetery (1909, Kunsthalle, Hamburg) closed the show. The picture is a vivid memory of a trip to Tunisia from December 1904 to April 1905 with Gabriele Münter, who photographed the journey with her new Kodak Brownie. A wall text reminded visitors of the comprehensive exhibition of Islamic art held in Munich in 1910, Masterpieces of Mohammedan Art. Attracted perhaps by a brilliant poster by Julius Diez, Kandinsky and Macke were impressed by the display of thousands of decorative art objects and manuscripts; Henri Matisse came to Munich to see the show in May 1910.[29] By that time Delacroix's proposal to send French artists to North Africa had been implemented. Conceived on the lines of the Villa Medici, the Villa Abd-el-Tif was established in Algiers in 1907 as a residence for artists. Rome was indeed no longer only in Rome, and the prizewinners ("les Abd-el-Tif") continued to receive stipends until independence in 1962.

Viewers completing the journey from Delacroix to Kandinsky in Brussels emerged in a superb temporary bookstore, imaginatively stocked for the exhibition not only with souvenirs, but with a full range of Orientalism books, from Gerald Ackerman on Gérôme to John Zarobell on Algeria. One table displayed the abundant literature on the harem and on female travelers in the Orient, another held a panoply of books by, inspired by, and refuting Said. Browsing the previous writings of the stellar team of contributors to the Orientalismus catalogue gave rise to regret that their essays were not indexed. The editors did provide an alphabetical checklist by artist with illustration numbers and page references. A reader can find exhibited works, but only repeated searches through the book turn up allusions to, say, Baalbek or Biskra or to Edward Said himself. The catalogue is otherwise attractively designed, with each work reproduced in color; for some objects these are the only readily available illustrations. Equally well conceived was the Brussels website architecture. Both exhibition and catalogue handled the complex subject thoughtfully, enabling an overview of nearly 100 artists from various backgrounds, who invented their Orients with differing motives.

The show's package tour of Orientalism included ports of call requiring a fresh nod at questions about depictions of European superiority and the political uses of this art; these questions were first raised in 1983 when Linda Nochlin applied the insights of Said to a few nineteenth-century painters.[30] The final page of the catalogue summarizes the contributions of Said and Nochlin to what became a fervid debate and cites the refutation of their views by John M. MacKenzie in his impressive book of 1995 (273).[31] The exhibition, short on theory, delivered instead a wealth of material enabling visitors to interrogate the issues for themselves in the face of original objects. It offered, for example, a rare opportunity to consider work by impoverished painters like Edward Lear or Gustav Bauernfeind, struggling to earn a living. Bauernfeind, who settled in Jerusalem, could be compared with Etienne Dinet, who painted in Laghouat on a travelling fellowship awarded him by the French government in 1885; Dinet would later make Algeria his second home and convert to Islam. By contrast, the well-to-do Gérôme was represented in the show with an assortment of subjects. Gérôme's standard merchandise of marble-like bathers – he claimed to have painted the architecture of The Moorish Bath (1889–90, Najd Collection) while stark naked himself in a Bursa hammam – was available for study near Fellaheen Drawing Water, Medinet-el-Fayum, where he enhanced with veiled women a landscape photograph by Albert Goupil, his brother-in-law. Also nearby was Gleyre's topless Nubian Woman (1838, Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts, Lausanne), who could be compared in Brussels with a modest female Fellah painted by Princess Mathilde Bonaparte. A first cousin of Emperor Napoleon III, the princess earned praise from Gautier for her veiled figure at the Salon of 1861.

As varied as their careers and their work selected for the show were the duration and frequency of the artists' stays and their impulses to travel, if they traveled at all: J. A. D. Ingres journeyed no further south than Naples and based his hammam scenes on the Turkish Embassy Letters (1763) of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Reasons to undertake a voyage to the Orient ranged from sex tourism to scouting for authentic Bible locations. Some artists were simply curious or convalescent, some collected costumes and studio props, and others carried out official commissions – at times under military escort. The painters' common goal, however, was to exhibit and sell pictures, inspired by a motif or composed from photographs, sketches, or memories. That late in the twentieth century these artists faced charges of complicity with "the corporate institution for dealing with the Orient," as Said called Orientalism, prompted only a few critics to walk through the show assessing innocence or guilt of racism or colonialism. More often, the charge was that Europeans looking at the East had produced, not the clichéd Other that led to the Iraq War and Abu Ghraib, but pure kitsch: "Hammy, hilarious," a woman remarked in Munich, recommending the exhibition to a friend. Even if the curators may cringe at any utterance of the K-word, the German viewer's reaction hints at a latent delight in the material that led them to summon it for display. The organizers put together a fascinating, open-minded survey, allowing paintings and sculpture to drive the narrative and admitting diversity to offset stereotypes.

Jane Van Nimmen

Independent scholar, Vienna, Austria

vannimmen[at]aon.at

Unless otherwise noted, all translations are by the author.

[1] Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1978), 1.

[2] This review does not include the third venue; some ten additional objects were scheduled to be exhibited only in Marseille. For an insightful review by Didier Rykner of the show in Marseille, see La Tribune de l'Art.

[3] Bergeret had depicted the fifteenth-century Turkish conqueror of Constantinople, Mahomet II Fatik, in a proto-orientalist painting, purchased by the French government from the Salon of 1817 and now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux. He recycled the figure of the conqueror as the Algerian master in Filippo Lippi and added to the new picture a slave from the 1817 painting; see Bergeret's initial drawing, now in the Peabody Art Collection, on loan to the Baltimore Museum of Art.

[4] Foreign excavations depended on permit approvals by Osman Hamdi Bey as the Ottoman Empire's chief archaeologist and the author of art export legislation. By 1886 the Germans had been allowed to ship to Berlin most of the finds of their team at Pergamon. Both the French government (1892) and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia (1895) purchased paintings from Osman Hamdi as a diplomatic gesture of gratitude. See the fascinating online exhibition catalogue "Archaeologists & Travelers in Ottoman Lands" (Penn Museum, Philadelphia, September 26, 2010 – June 26, 2011), including excellent essays and bibliographies on Osman Hamdi and his reception. For his work as an archaeologist, see also Ussama Makdisi, "Ottoman Orientalism," The American Historical Review 107:3 (June 2002): 768–96. The historian Edhem Eldem discusses Osman Hamdi's orientalist views in his introduction to Un Ottoman en Orient: Osman Hamdi Bey en Irak, 1869–1871 (Paris: Actes Sud, 2010).

[5] The savants (some 160 scientists, engineers, architects, balloonists, linguists, and artists) are the subject of studies by Yves Laissus, L'Egypte, une aventure savante: Avec Bonaparte, Kléber, Menou, 1798–1801 (Paris: Fayard, 1998) and Erin A. Peters, "The Napoleonic Egyptian Scientific Expedition and the Nineteenth-Century Survey Museum" (.pdf) (master's thesis, Seton Hall University, May 2009), 15–22.

[6] Dominique Vivant Denon, Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute Egypte, pendant les campagnes du général Bonaparte, 2 vols. (Paris: P. Didot Ainé, 1802). For the etching of savants with telescopes on a tower near the Bay of Abukir, see Plate 15, no. 5, bottom illustration. In 1836 the British Museum acquired most of Denon's drawings for the plates; see his preliminary drawing for Plate 15. In the passage on the battle and the description of Plate 15, no. 5 (pp. 34 and 231 in the 1802 edition), Denon misdated the arrival of the English fleet to 14 fructidor in the Republican calendar (August 31); Nelson's attack began on 14 thermidor (August 1, 1798).

[7] Denon illustrated in Voyage (Plate 66, no. 1) the temple ruin with hieroglyphs at Aswan.

[8] The Bibliotheca Alexandrina has produced a searchable Internet site for Description de l'Egypte. On view in Brussels were Vol. 3, Antiquités III, p. 26, Pl. 13, details of colossi, and Vol. 7, Etat moderne, I, p. 68, Pl. 33, Sultan Hassan Mosque, Cairo.

[9] The victors in Egypt seized the Rosetta Stone from the French; the stele has been on view in the British Museum since 1802.

[10] Abbot Albert Nagnzaun of St. Peter's, the ancient Benedictine abbey in Salzburg, was the subscriber who commissioned the commode in 1828 from the Viennese sculptor Johann Högl. The Dendera temple was depicted by Jean-Baptiste Lepère in Description, vol. 4, Antiquités IV, p. 60, Pl. 29. Denon's ink drawing of the temple for Voyage (1802), Pl. 39, is in the British Museum.

[11] The pair shown at the Hypo-Kunsthalle has a strong connection with Munich. The statues were commissioned by Eugène Beauharnais, Napoleon's stepson, who married a Bavarian princess and whose tomb by Bertel Thorvaldsen and Pietro Tenerani is in St. Michael's church in Munich. Beauharnais added a new Egyptian portico to the Parisian residence he purchased in 1803 at 78 rue de Lille; the marble figures by Pierre-Nicolas Beauvallet stood in niches on each side of the portico. At least four possible sources for the statues were expropriated in 1798 under Napoleon and remained in the Louvre until his fall: the Vatican figure of Antinous (inv. 22795) and three statues from the Albani collection purchased for Munich in 1815 by Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria (inv. WAF 14, WAF 15, and WAF 24, Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst München).

[12] Soon after Hawkshaw's report to the Khedive, British pressure on the Ottoman government resulted in a ban on the corvée for the Egyptian canal project. A New York Timeseditorial (September 6, 1863) pointed out the hypocrisy of the critics: the British had used forced labor themselves to build the railway from Alexandria to Suez. As an engineer, Hawkshaw believed the canal was feasible, but doubted that Poynter's Israelites could possibly move the granite lions; the patron insisted that the artist paint in more slaves. Poynter offered in Israel in Egypt the most vivid cultural pastiche since the Egyptian Court in the Crystal Palace at Sydenham (1854), or the earlier imagined geography in a painting (1824) by the French publisher Charles Panckoucke. In his "summary of all Egypt," the Nile ran past major monuments from the first cataract at Syene to the delta, and Panckoucke replicated the picture as the hand-colored frontispiece for his new edition of Description de l'Egypte.

[13] Chassériau destroyed his painting after the Salon jury rejected it in 1845; drawings survive in the Louvre (290). The earlier of the two Cleopatras was by German von Bohn (1841), who never saw the Nile, and the second by Hans Makart (1874–76), who traveled to Egypt in 1875.

[14] Letter, Delacroix (in Tangier) to Auguste Jal, June 4, 1832; see Correspondance générale d'Eugène Delacroix, André Joubin, ed., 5 vols. (Paris: Plon, 1936–38), 1:330. The expression "Rome n'est plus dans Rome, elle est toute où je suis"goes back to Pierre Corneille (Sertorius) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (Julie, ou La nouvelle Héloïse). More recently, it had been altered to "Rome n'est plus dans Rome, elle est toute à Paris," in a refrain sung during the procession celebrating the arrival of the Apollo Belvedere and other art works from Italy at the festival held on the Champ de Mars in Paris on 9-10 thermidor an VI (July 27–28, 1798).

[15] The phrase "croquis faits sur le pommeau de la selle," quoted by Peltre, is from Théophile Gautier, "Atelier de feu Théodore Chassériau," L'Artiste (March 15, 1857): 211. Like Gautier, Peltre has a gift for vivid description; her L'Atelier du voyage: les peintres en Orient au XIXe siècle (Paris: Gallimard, 1995) is an excellent brief summary.

[16] Gérôme's canvas from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, slightly smaller than the Musée d’Orsay version and also dated 1867, was included in the show. Osman Hamdi Bey's delicate Koran Instruction set in the Green Mosque in Bursa (1890, Najd Collection, Geneva) and Gustav Bauernfeind's Wailing Wall, Jerusalem (ca. 1880, The Orientalist Museum, Doha) were among the ten paintings in this section, labeled in Brussels "Crossroads of religions."

[17] Merson's Rest on the Flight into Egypt (1880, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nice), seen in all three venues of the exhibition, is close to an 1879 version in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. A picture with the same title in Hearst Castle, San Simeon, California, is also dated 1879, but the setting is dawn; see Emily Beeny, "Merson et les Etats-Unis," in L'Etrange Monsieur Merson, exh. cat. (Lyon: Lieux Dits, 2008), 199–219. The Merson exhibition at the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rennes, is discussed in a review by Didier Rykner in The Art Tribune.

[18] For a smaller version of The First Mass in Kabylia, see Horace Vernet: 1789–1863, exh. cat. (Paris: Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, 1980), no. 91. On Vernet's three colossal battle pictures for the Constantine Room at Versailles, see John Zarobell, Empire of Landscape: Space and Ideology in French Colonial Africa (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 39–46. Vernet had hastened to Algeria before the end of October 1837, but he missed the fierce street fighting in Constantine. He was in Russia in 1843 when the duc d'Aumale, a son of Louis-Philippe, led the surprise attack on the mobile capital (smala) of the chief Berber leader in Algeria. Vernet depicted the event in one of the largest history paintings of the nineteenth century, The Capture of the Smala of Abd el-Kader at Taguin, 16 May 1843 (1845, Smala Room, Musée de l'Histoire de France, Château de Versailles).

[19] Peter Benson Miller, "La vision officielle de l'Algérie sous le règne de Napoléon III," De Delacroix à Renoir: L'Algérie des peintres, exh. cat.(Paris: Hazan/Institut du Monde Arabe, 2003), 152–66. Miller notes (cat. no. 75) that Vernet sent the picture to the Exposition Universelle in 1855 under the title Campaign in Kabylia, Governor-General Randon (no. 4153).

[20] On Fromentin, see the opening chapter of Roger Benjamin, Orientalist Aesthetics: Art, Colonialism, and French North Africa, 1880–1930 (Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 2003), and Zarobell (2010), chap. 4 (as in no. 18 above). Fromentin's Un été dans le Sahara (1854 in La Revue de Paris, 1857 as a book) closed with the thought that when the writer would leave Laghouat for the last time, he would look back bitterly and salute with deep regret "this menacing horizon, so desolate and . . . so justly called Land of thirst."

[21] Hergé, the Belgian comic strip artist, also borrowed Fromentin's catchphrase for one of the most admired sequences in all of Tintin, the desert scene in Le crabe aux pinces d'or (1941).

[22] The Fromentin canvas, purchased by the state at the Salon of 1859, is now in the depot of the Musée de la Chartreuse in Douai; Bompard's reduction inspired by Fromentin is in the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire, Narbonne.

[23] Christine Barthe, curator of photography at the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, identified the Enkess life cast; see her essay "Models and Norms: The Relationship between Ethnographic Photographs and Sculpture" in Laure de Margerie and Edouard Papet, Facing the Other: Charles Cordier, Ethnographic Sculptor, translated from the French by Lenora Ammon, Laurel Hirsch, and Clare Palmieri, exh. cat. (New York: Henry W. Abrams, 2004), 93–126. The exhibition originated at the Musée d’Orsay, and the installation at the Dahesh Museum of Art was scrutinized in a lengthy review by Barbara Larson in The Art Bulletin 87:4 (December 2005): 714–22.

[24] Both bronzes are in Osborne House, East Cowes, Isle of Wight; see Facing the Other, nos. 480, 481, p. 205). In 1851, the French State commissioned casts for the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle (the pair exhibited in Munich, now in the Musée de l'Homme and described in Facing the Other, nos. 486, 487, p. 206).

[25] The large painting, commissioned in 1861 from Pils by Emperor Napoleon III, was lost in the Tuileries fire in 1871. Miller (2003, "La vision officielle," as in n. 19 above) includes a detail and an illustration (pp. 152, 160) of a sketch now in the Kenneth Jay Lane collection, New York, which uses the figure for which the head in Narbonne (Musée d'Art et d'Histore) is a study. That head does not appear in a second sketch for the painting, acquired in 2006 by the Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly. Miller's essay is insightful on the role of the Kabyles in the work of Pils and on the contradictions in Emperor Napoleon III's dream of an Arab kingdom.

[26] A photograph (ca. 1855, Musée d’Orsay) from Gérome's collection of a model posing as the Arnaut with a rifle over his shoulders is illustrated in the Orientalismus catalogue (40–41).

[27] The straightforward diary kept by de Famars Testas on this journey is an invaluable record of art tourism; see "Le journal de voyage de Willem de Famars Testas, 1868," in Album de voyage: des artistes en expédition au pays du Levant, exh. cat. (Paris: Association Française d'Action Artistique / Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1993), 89–217. On de Famars Testas and his earlier travels, see Visions d'Egypte: Emile Prisse d'Avennes (1807–1879), exh. cat. (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 2011).

[28] Painted during his first visit in 1881, Arab Festival (sometimes called The Mosque) is Renoir's best-known view of Algiers, famous not only because Claude Monet bought it in 1900, but also because it is so innovative. See Roger Benjamin, ed., Renoir and Algeria, exh. cat. (Williamstown: Clark Art Institute, 2003), and Benjamin's Orientalist Aesthetics (as in no. 20), chap. 2.

[29] In his essay for the Orientalismus catalogue, Benjamin discusses Matisse's work in Biskra in 1906 and his productive stays in Tangier in 1912 and 1913 (216–21). A Matisse bronze after Barye (1899–1901) was shown in Munich, and three Matisse paintings would join the exhibition in Marseille.

[30] Linda Nochlin, "The Imaginary Orient," Art in America 71:5 (May 1983): 118–31, 187–91. In her essay Nochlin chided Donald Rosenthal, curator of Orientalism: The Near East in French Painting, 1800–1880 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Memorial Art Gallery, 1982), for acknowledging the link between Orientalism and colonialist expansion but deciding not to confront the issue.

[31] The historian of imperialism John M. MacKenzie, deploring a lack of detail in the earlier monolithic views of Said and his followers, wrote a counter-polemic, Orientalism: History, Theory, and the Arts (Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 1995). For a discussion and comments on the lingering impact of Said's book, see the Guardian series "Orientalism at 30" in June 2008, concurrent with the opening weeks of the exhibition in London at Tate Britain, The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting.