The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

James Pradier (1790-1852) et la sculpture française de la génération romantique. Catalogue raisonné.

Claude Lapaire

Zürich/Lausanne: Swiss Institute for Art Research; Milan: 5 Continents Edition, 2010.

512 pp; 838 duotone illustrations

Cost: CHF 140. (ca. $120.)

ISBN: 978-88-7439-531-6

Charles Baudelaire blamed him for the "pitiable state of sculpture today" and alleged that "his talent is cold and academic,"[1] while Gustave Flaubert felt that he was "a true Greek, the most antique of all the moderns; a man who is distracted by nothing, neither by politics, nor socialism, Fourier or the Jesuits […], and who, like a true workman, sleeves rolled up, is there to do his task morning till night with the will to do well and the love of his art."[2] Both are discussing the same man, one of the leading artists of late Romanticism and the "king of the sculptors" during the July Monarchy: Jean-Jacques Pradier (23 May 1790 – 4 June 1852), better known as James.[3]

Born in Geneva to a hotelkeeper, Pradier left for Paris at the tender age of 17 to follow his elder brother, Charles-Simon Pradier, the engraver. In 1809, he entered the studio of François-Frédéric Lemot to study sculpture, and registered at the École des Beaux-Arts in February 1811, the same day as Théodore Géricault (21). It was on that occasion, and in an attempt to be fashionable, that he anglicized his name to James. With his Neoptolemus Prevents Philoctetes from Loosing His Arrows Against Ulysses (cat. 7), Pradier won the Prix de Rome in 1813, which enabled him to stay at the Villa Medici as a pensioner until late 1818 (fig. 2). There he met Jean-Pierre Cortot, Jules Robert Auguste, and David d'Angers, as well as Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres and many others. His successful career continued immediately upon his return to Paris with his Salon debut in 1819 where he showed two sculptures that he had executed in Rome: the plaster Bacchante and Centaur, which is now lost and only recorded in a drawing (cat. 15) and the marble Nymph, now in Rouen (cat. 10), which earned him a gold medal (fig. 3). Soon followed some of the most prestigious commissions for the Restoration and the July Monarchy, such as the commemorative Monument to the Murdered Duc de Berry for the cathedral of Saint-Louis at Versailles in 1821 (cat. 21), four bas-reliefs of Fame for the Arc de Triomphe at the Place de l'Étoile in 1829 (cat. 58 – 61), the monumental statues of Liberty and Public Order for the Chamber of Deputies in the Assemblée Nationale in 1832 (cat. 66 and 67) (fig. 4), one of the reliefs on the main facade of the same building in 1838 (cat. 119), the seated figures of Strasbourg and Lille for the Place de la Concorde in Paris (cat. 103-104), several statues for the Palais du Luxembourg (cat. 136-144), as well as numerous portrait statues for Louis-Philippe's Galeries Historiques at Versailles from 1836 onwards (cat. 107, 108, 126, 127, 133, 158, 206, 320), and finally, in 1843, the twelve colossal Victories that guard Napoleon's tomb at the Dôme des Invalides (cat. 209-220). Pradier's reputation reached his home town of Geneva very early, and in 1830, a committee of dedicated citizens asked him to execute a monument to Jean-Jacques Rousseau for the newly constructed Ile Rousseau in the Rhone river. This piece (cat. 50), which is much indebted to Houdon's Voltaire, was Pradier's first major bronze and the cause of much anxiety as well as a financial loss of 12,000 francs due to the technical difficulties he encountered during the casting process; it was finally erected in 1835. Other official commissions included a Virgin Mary for the cathedral at Avignon (cat. 110), and the monumental Fountain de L'Esplanade at Nîmes (cat. 265). Throughout his artistic life, Pradier continued to execute portrait statues, busts, and statuettes of the royal family and many contemporary luminaries in the political and cultural arenas, of which his Third Bust of Louis-Philippe (cat. 84), and the Memorial to the Count of Beaujolais of 1835-39 (cat. 97) arguably show him at his best (fig. 5).

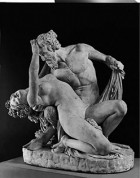

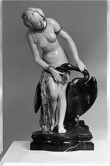

Apart from such prestigious commissions, Pradier is today remembered for his female nudes and erotic groups that were largely designed as objects of desire for male spectators. A long series of endlessly bending and stretching sensuous female figures camouflaged as classical heroines commences with the early Nymph that Pradier had brought back from Rome (cat. 10). This is followed by the robust sensuousness of the Three Graces of 1825-31 (cat. 32), an ambitious articulation that in the words of Horst W. Janson "would have embarrassed Thorvaldsen and would have been unthinkable for Canova,"[4] to be outdone by the sensationalism of his Satyr and Bacchante at the Salon of 1834 (cat. 62, fig. 6). The piece caused a scandal: some claimed to recognize the features of the sculptor and his former mistress, Juliette Drouet, who by then had begun an affair with Victor Hugo (34-35). Others like Gustave Thoré excoriated its exhibition of "dirty thoughts and disgusting action" (267). Nevertheless, a lucrative flow of female nudes – "statues de chaire" – continued in the 1840s, with Odalisque (cat. 161, fig. 7), Cassandra (cat. 207), Phryne (cat. 232, fig. 8), Pandora (cat. 263), Nyssia (cat. 307) and Danaide (cat. 358), among others, all alluding in one way or another to famous courtesans or women of some reputation, and therefore offering an erotic spectacle to male voyeurism. These figures led Pradier to promote serial editions of his work through a vast number of small-scale bronzes, plaster casts, and terra cottas that he edited from 1830 onwards. Some were reductions of his large-scale pieces whereas others were specially designed for this sort of market. But these examples of small-scale erotica like the variations of his femmes couchées – sleeping women draped over lion-skin rugs or cushions (cat. 184-189), or entangled in giving sexual pleasure (cat. 429) betoken a shrewd commercialism (fig. 9). There is, however, another side to Pradier's small-scale work as seen in his late Leda of 1851, an exquisite chryselephantine sculpture that he produced in exploration of new materials and that was perhaps a result of his collaboration with the jeweller, François Désiré Froment-Meurice (cat. 356, fig. 10). Here Pradier revived an ancient technique that was known from classical sources, and which, at the time, was regaining attention through archaeological reconstructions of the Athena Parthenos and the Zeus Olympos, both lost colossal chryselephantine sculptures that classical sources record as the masterpieces of Phidias.[5] Continuing the classical vein, Pradier's famous Sappho Sitting (cat. 366) that he exhibited in the Salon of 1852, shows his skill in successfully rendering the painfully restrained, palpitating drama of the ancient Greek poetess (fig. 11). Combining the nobility of marble and the dignity of the subject in a clear form, he achieved a powerful image that would at the same time stand for a meditative intensity and the expression of reflection and despair.

Throughout his career, Pradier was showered with professional honors and prestigious posts. He was elected professor of sculpture at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1827, made Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur in 1828, and Officier de la Légion d'Honneur in 1834. He sold more Salon entries to the French government between 1819 and 1852 than any other sculptor at that time, and his work was distributed throughout the national museums in France. In contrast to this, he received fewer public commissions than his competitors: he was given none of the large reliefs for the Arc de Triomphe, only the smaller figures of Fame (cat. 58-61), nor did he get a commission for the tympanum of La Madeleine or any other major architectural sculpture (80-81). By the time of his death in 1852, however, he was considered one of the leaders of modern French sculpture and along with Jean-Pierre Cortot, David d'Angers, and François Rude, a favourite of the July Monarchy (81).

Claude Lapaire's meticulously researched monograph and catalogue raisonné of Pradier's work is the latest in a series of catalogues published by the Swiss Institute for Art Research, and is intended to foster the rehabilitation of the much maligned – and still widely forgotten – sculptor. On a solid foundation of rich historical and biographical details furnished by epistolary and archival documentation, supported by a plethora of critical sources, Lapaire reconstructs the life and work of one of France's outstanding personalities in nineteenth century art. Free from speculation and value judgements, written in clear, unequivocal language, Lapaire's text is not only highly informative, but also a delight for the reader. The book is elegantly produced and enriched with 837 duotone illustrations, while the text is illuminated by an excellent, but unobtrusive critical apparatus.

The publication is divided into three sections: an analytical biographical part, the critical catalogue, and the apparatus. The latter includes a handy chronology of the artist's life and posthumous reception up to 2006, the reproduction of all the different signatures used by the artist on his single-authored sculptures and the many bronze editions, a concise list of all used sources, a chronologically organised bibliography subdivided into an alphabetical list by author, as well as valuable indices of cited works of art, places, and personal names.

The biographical part offers an extensive survey of the artist's life and work, without, however, getting lost in titillating (or sordid) details of his private life, such as his occasionally stormy love affairs or the divorce from Louise Dupont. Lapaire does not try to explain Pradier's work through his biography; he, instead, does meticulously list the substantial income that the artist received from public commissions, including the inordinate sum of 240,000 gold francs for the twelve Victories that guard Napoleon's tomb (49-50). He thus reveals Pradier as what in today's world would be considered a "star." Here, one might have expected a more detailed account of the art market during the July Monarchy and some comparative prices that François Rude and David d'Angers had collected for their work in order to assess Pradier's status within the context of his competitors. It is perhaps also regrettable that the Catalogue de Vente après décès of 1852 has not been reproduced, or that at least a table of the prices achieved in that sale be provided, as is the case, for example, with the list of public commissions (49-50) and all Salon participations (74-75).

In his analytical section, Lapaire also offers detailed chapters dedicated to various aspects of Pradier's œuvre: small-scale sculptures – "those little nothings" ("ces petits riens") as the artist had called them (96), "statuettes de genre," edited bronzes, plasters and terra cottas, such as the aforementioned erotica (fig. 9). Here Lapaire shows that in contrast to Antoine-Louis Barye, for example, the edited sculptures were not a major source of income, but rather an important marketing tool – a sort of merchandising – that would ensure the artist's popularity among the bourgeoisie (97). Other chapters explore the artist's working conditions, his workshop, assistants, his methods from sketch to finished marble or bronze, the various materials he used and the different ways of marking his pieces. Lapaire also traces the relationship between Pradier and his seventy or so students, of whom Antoine Etex, the author of Géricault's funerary monument in the Père Lachaise cemetery, is probably the best known (131-139).

In his analysis, Lapaire also offers the first iconographical and socio-political reading of Pradier's creative output. He explores the artist's great themes and shows how pragmatic some of the titles may have been. For example, Pradier's famous Nyssia (cat. 307), reproduced on the publication's cover, existed for several years under the prosaic description "woman holding up her hair over a lavabo" (fig. 1). Before the statue could be sent to the Salon, however, it needed a more uplifting title, which the artist quickly borrowed from the heroine in Théophile Gauthier's novel Le Roi Candaule (141 and 367). Pradier would of course follow carefully developed allegorical concepts when dealing with public commissions, and he certainly took care of the marketability of a specific persona, yet one is left with the suspicion that – once again – his female nudes were crafted not just out of love for the opposite sex, but also with commercial gain in mind.

Lapaire's biography is solid, rich, and detailed. It, however, does leave space for further research into those periods or areas of the artist's life and work that still remain rather obscure, such as Pradier's Italian sojourn as a pensioner at the Villa Medici. Here, the sculptor's own drawings and letters from friends and colleagues could yield a wealth of information, as should archival material to which Bruno Chenique has led scholars on French Romanticism with his research on Théodore Géricault.[6] Another fruitful ground of inquiry would be Pradier's reaction to the painter Henri-Joseph Forestier, or his Swiss compatriot Jean-Victor Schnetz, both of whom were present in Rome when he was there. From this, one might learn whether he absorbed similar motifs as Forestier, Schnetz, and Géricault when in the eternal city, and whether he joined them in their activities, or even travelled with fellow artists to other places. Etex, after all, mentions Pradier, in particular, as one of Géricault's friends in his account of 1885, Les trois tombeaux de Géricault, a source ignored by Lapaire,[7] as is Maxime du Camp's Souvenirs of 1883.[8] One might also discover how Pradier perceived the work of the "Danish Phidias" Berthel Thorvaldsen, whose studio with its display of original plasters was a pilgrimage site for countless art lovers and aspiring artists, and who was restoring the late archaic tympanum figures from the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina, which had been acquired by Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria in 1812. These pieces were the first major samples of non-classical Greek sculpture that Pradier would have encountered, and that may have had, as Lapaire points out (149), a late effect on his Sagesse repoussant les traits de l'Amour of 1845 (cat. 262).[9] There is also the mystery surrounding the shooting at the Villa Medici which led to Pradier's expulsion just weeks before his time as pensioner came to an end, and which is taken as an example of the artist's impulsive nature (27).

Another dimension that remains to be explored in more detail is Pradier's stylistic idiom within the notion of "Greekness" during the Restoration and July Monarchy. Although Lapaire offers a brief survey of "classical topics," and a handful of ancient models that were a source in one way or another for a couple of the artist's works (144-150), the matter is more complex, especially since, as pointed out before, Pradier was considered "a true Greek." It remains to be asked to what extent the artist's "true Greekness" differed from the traditional and reputedly "false" notion – as it apparently was indicated to be during his lifetime. Since the book's title announces the exploration of "French sculpture from the Romantic generation," a contextualisation of Pradier's neo-classicism would have helped to better assess his achievements and to understand the extraordinary reputation that he enjoyed during his lifetime. Such an approach would need a wider comparison with the older, "Canovian" concept of "Greekness" as adumbrated in Antonio Canova's own statement to Quatremère de Quincy: "To become a truly great artist, you must do more than just borrow here and there from antique pieces and throw them together without any sort of evaluation. Better study Greek examples day and night, be steeped in their style, impress it in your mind; and then develop your own style."[10] In light of this approach to the study of classical sculpture, one might also consider the conditions under which Pradier encountered ancient art. During his formative years, the young sculptor would have been able to study the best classical pieces then exhibited in the Musée Napoléon, which since 1807 had united the most precious sculptures from French and Roman collections. Upon his return from the Villa Médici in 1819, however, most of these had gone, while newly arrived at the Louvre were then widely unknown Parthenon sculptures from the Choiseul-Gouffier collection (in 1818); the Venus de Milo came in 1821, and fragments of the Zeus temple at Olympia arrived as a gift from the Greek Senate in 1829. Thus, while Pradier was educated within the old, "Canovian" neoclassical mindset based on an aesthetic principle that placed Roman copies of Greek originals, such as the Apollo Belvedere, at its core, he produced his art mainly within a period that gradually discovered ancient Greek originals and even pre-classical sculpture. He, therefore, had to adapt to a new notion of "Greekness," and to a changing attitude of taste. The question remains, however, as to how far he absorbed these new tendencies in his work.

A third area that deserves further investigation is the arguably impressive corpus of Pradier's female nudes. They account for 24% of his artistic output: 122 large and small-scale sculptures in a total œuvre of 506 undisputed pieces, as against only twelve male nudes, and none of them in editions. Lapaire points out that between 1819 and 1852 Pradier had shown a large female nude at every Salon (155). Compared to this, Kathy Anne Mc Lauchlan has reported, that among the nudes produced as "figures d'étude" by pensioners at the Villa Medici during Pradier's lifetime, only 27 were female in contrast to 118 male nudes. Of these, however, a third of the female nudes were presented at the Salon, while less than a quarter of their male counterparts managed to get into the same venue.[11] This may beg a question or two, especially in light of a host of gender-based inquiries at the end of the twentieth century that challenge the dominant models of nineteenth-century visual culture.[12]

The backbone of Lapaire's book is, undoubtedly, his comprehensive illustrated catalogue raisonné of 506 undisputed sculptures and 72 attributions, given in 578 detailed entries. This is reasonable to focus upon, since, in terms of artistic activity, it includes what Pradier was most famous for, and leaves out the bulk of his drawings, sketches and paintings, unless they record a lost piece (e. g., cat. 15) or provide further documentary evidence (fig. 3). Each entry has been researched in depth and appears chronologically with an original and sometimes conventional or alternative title, followed by a technical description, present whereabouts, history and critical reception, other versions or editions, bibliographical references, and thorough analytical commentary explaining the creation and evolution of each piece. The catalogue entries of Pradier's edited work also list numerous e-bay sales, giving a frightening glimpse into what the future might hold for upcoming generations of art historians, and giving ample evidence of Lapaire's meticulous, sleuth-like investigation. The result is a clear presentation of primary data and sources. In addition, each entry is reproduced in splendid duotone illustrations, many of which show works not previously published or reproduced from several novel angles. In sum, Lapaire has provided an enormously useful and careful compilation of a large body of material, which will make this elegantly designed book a reference tool for all future studies in the field. Moreover, he has rendered Pradier's œuvre easily accessible and launched it into the mainstream of nineteenth-century art historical research.

Marc Fehlmann

Dr. phil. Marc Fehlmann FRSA

Departement Altertumswissenschaften

Klassische Archäologie

Universität Basel

Petersgraben 51

CH – 4051 Basel

marc.fehlmann[at]unibas.ch

[1] Salon of 1846, in Marcel A. Ruff (ed.), Charles Baudelaire, Œuvres complètes (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1967), 257-258 (translation by the author).

[2] Gustave Flaubert in a letter to Louise Colet, dated 30 August 1846, in Jean Bruneau (ed.) Flaubert Correspondance, vol. 1 (Paris: Gallimard, 1973), 321, partially quoted in Claude Lapaire, James Pradier (1790-1852) et la sculpture française de la génération romantique. Catalogue raisonné (Zürich/Lausanne: Swiss Institute for Art Research; Milan: 5 Continents Edition, 2010), 41 (translation by the author).

[3] Louis Stephane Leclerc, Examen critique de l'exposition des beaux-arts en 1845, quoted in Claude Lapaire, James Pradier (as note 2), 206.

[4] Horst W. Janson, Nineteenth-Century Sculpture (London, Thames and Hudson, 1985), 107.

[5] Quatremère de Quincy offered his reconstruction of the Olympian Zeus already in 1815 as Le Jupiter Olympien, ou l'art de la sculpture antique considéré sous un nouveau point de vue, (Paris: Chez De Bure Frères, 1815).

[6] Bruno Chenique used the Registre des Passeports visés of the French Embassy to the Vatican to trace the movements of French artists in Rome, especially to establish Théodore Géricault's journeys and circle of friends. See for this Bruno Chenique, "Géricault, une vie" and "Documents" in Sylvain Laveissière, Régis Michel, and Bruno Chenique, Géricault exh. cat. (Paris: Grand Palais, 1992), 261-308, and 317-324. The exhibition was on view from October 10, 1991 to January 6, 1992.

[7] Antoine Etex, Les trois tombeaux de Géricault, Paris: E. Perrin 1885, 15: "Il [Géricault] allait à Rome retrouver des artistes qu'il avait connus à Paris: les sculpteurs, prix de Rome, Giraud, [...], David d'Angers, notre cher maître Pradier."

[8] Maxime Du Camp, Souvenirs littéraires, 2 vols. (Paris: Hachette, 1883), esp. vol. 2, 297-298, on Pradier praising a drawing by Géricault, which represented a bas-relief of Mithridates.

[9] Lapaire rightly links the severe style of this bronze to an article on the Aegina sculptures in L'Artiste of 1844 and to an archaizing statue of Athena Promachos in Naples, which the artist probably had seen in 1842 (149, 345).

[10] Antonio Canova in a letter dated 26 November 1806, quoted by Agostino Lombardo, "An English Parodox" in Giuseppe Pavanello and Giandomenico Romanelli, Canova, exh. cat. (Venice and New York: Marsilio, 1992), 11. This is the catalogue of the exhibition held at the Museo Correr, Venice, and the Gipsoteca, Possagno, March 22 to September 30, 1992.

[11] Kathy Anne McLauchlan, French Artists in Rome 1815-1863 (Ph.D. diss, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 2001), 204 (as yet not published).

[12] Linda Nochlin, Griselda Pollock, Alex Potts, Thomas Crow, and Abigail Solomon-Godeau, among others, have paved the way for an exploration of 19th century French art production and its categories beyond normative assumptions of female representation, stereotypes and inscriptions.