The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Le Douanier Rousseau: L’innocence archaïque

Musée d’Orsay, Paris

March 22–July 17, 2016

Catalogue:

Le Douanier Rousseau: L’innocence archaïque /The Douanier Rousseau: Archaic Naivety.

Gabriella Belli and Guy Cogeval.

Paris: Hazan, Les éditions du Musée d’Orsay, 2016.

270 pp; 180 illustrations (color and b&w); appendices; exhibition checklist; chronological biography.

$32.95

ISBN: 8866482560 (English)

The unusual nature of [Henri] Rousseau’s work, which bridges two centuries, has earned it a significant place in the history of art, thus prompting the question: was he a product of the nineteenth century or an exponent of the twentieth?

To that question painted on its introductory wall, the Musée d’Orsay’s exhibition Le Douanier Rousseau: L’innocence archaïque has definitively answered: both (figs. 1, 2). Together, the Musée d’Orsay’s exhibit and its accompanying, plushly illustrated catalogue have mightily tackled that question, by tying the art of Henri Rousseau (1844–1910) to that of his contemporaries, those who succeeded him, and, albeit to a lesser extent, those who came before him.

With this initial question, curators Claire Bernardi and Laurence des Cars (with Elisabetta Barisoni) have paid intellectual homage to Michel Hoog. Now more than thirty years ago, Hoog’s essay in the catalogue for the 1985 Rousseau exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art raised a similar quandary with regard to the artist’s ponderous place in the history of art:

A problem persists with regard to the Douanier Rousseau. Admired by artists at the turn of the century (Pablo Picasso, Robert Delaunay, Wassily Kandinsky, Constantin Brancusi, and others), and defended by the same writers (led by Guillaume Apollinaire and Blaise Cendrars) who defended them, he is still difficult to fit into what we call modern art.[1]

The current exhibition has continued to trouble mythologies of Rousseau as a highly individual, self-taught “amateur,” whom poet and playwright Alfred Jarry once apocryphally dubbed “le douanier” (customs officer). That sobriquet has stuck, as have its associated tropes of Rousseau working as a Sunday painter that, as tropes tend to do, have flattened the artist’s colorful vie et oeuvre (life and work). Further, these tropes have occluded a finely nuanced understanding of Rousseau’s particular place in the history of art.

Curators Bernardi and des Cars have used the labels and legends around him to meditate on his place in the chronicle of art history and, in turn, to question the very validity of that narrative. Le Douanier Rousseau vividly, incisively, and comprehensively documented his connections to an international circle of artists beyond those who, at the invitation of Guillaume Apollinaire, memorably banqueted in 1908 at the makeshift Bateau-Lavoir studio to honor the elder artist. As the exhibit has elegantly illustrated, Rousseau made a distinct mark on those present that night and, thereafter, on his fellow Frenchmen Fernand Leger and Robert Delaunay, Italian Futurists and Magical Realists, German Expressionists and those affiliated with Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), American self-taught artists, and Surrealists worldwide.

Through a series of comparisons between Rousseau and especially German and Italian artists working between the two World Wars, Le Douanier Rousseau has retrieved the artist from the isolated place that he has long occupied in nineteenth- or twentieth-century art history. To do this, the exhibition has retraced some well-trodden territory—Rousseau as simpleton or naif—in order to chart new terrain about art history and temporalities. In the past century, art historians have employed different paradigms to narrate the story of modern art in relation to time. Diachronic art historical models, for instance, have split that history into a series of chronologically ordered distinct periods and movements, from Impressionism to Symbolism/ Post-Impressionism to Fauvism and so on. However much such an organizational scheme may be deployed straightforwardly (and to useful effect) in introductory art history courses or survey textbooks, it has been nimbly complicated by more synchronic art histories in their discussion of concurrent artistic practices and philosophies.

Still other art histories have looked to find threads uniting artists across time and space, for instance the threads of primitivism, infantilism, or naive art. Yet, to date, no paradigm (diachronic, synchronic, or otherwise) has adequately accounted for the art of Rousseau. Wrestling with how to classify him, in 1891, for instance, fellow painter Félix Vallotton described him as the “alpha and omega” of painting (65). Decades later in 1936, Alfred Barr, in his notorious chart printed on the front of Cubism and Abstract Art, flagged Rousseau as one of four artists unaffiliated with a period (Paul Cézanne, Odilon Redon, and Vincent van Gogh were the other three) but who laid the foundation for twentieth century art (65).[2] Le Douanier Rousseau acknowledged the artist to be typically “unclassifiable,” yet it also insisted that he was “wholly of his time and in a wholly singular way” (24).[3] In so doing, the exhibition proposed “archaism” as a useful paradigm through which to understand Rousseau’s art. But more than merely a reappraisal of one artist as a special case in art history, Le Douanier Rousseau serves as a studied meditation on how the history of art deals both with and in temporalities, while working to write a more fluid history of art liberated from more rigidly defined periods.

So what is meant by “archaism” here? Not to be confused with primitivism, infantilism or naive art, archaism must instead, as catalogue essayists Gabriella Belli and Guy Cogeval eloquently write:

. . . be interpreted not only as a problem of style and hence of the ‘clumsy’—or rather perhaps simplified and condensed—use of the customary tools of ‘cultured’ representation, namely space and perspective, composition and form, technique and colour, but also as the search for a primal identity, a sort of Holy Grail running all through the history of modern art. This is the primary answer to the question of what links Rousseau’s painting to the universe of Italian primitivism but also, and with no contradiction whatsoever, to the crude beauty of the American primitive painting of the 18th and 19th century (23).

Rousseau shared this “search for a primal identity” with the many compatriots installed here, from Piero di Cosimo to Giorgio de Chirico (33). His (and their) naïveté came to be sourced from, and shared with, newspaper illustrations, folk devotional imagery, “the idols of Africa and the South Seas, in archaic Greek sculpture and Egyptian painting, the mosaic art of late antiquity and Byzantium, and early medieval painting and sculpture” (33, 35). Due to his reliance on this source material, Rousseau can be understood to have pursued “authenticity to return to the roots, the primal sense of things” (23). This pursuit left his art imprinted with innocence, nostalgia, sentimentalism and, hence, archaism (70). Perhaps then, as Belli and Cogeval have asserted, any awkwardness and simplicity lies not in the pictures of Rousseau but in our stories of modern art history (24).

With its basic premise firmly established in the entryway, the exhibition proceeded to launch the visitor on a voyage through Rousseau’s vie and oeuvre. Its second wall listed key dates and events in the artist’s life. Typical, even expected, though such a wall may be, it here played a critical part: it traced Rousseau’s career from his first participation in the Salon des Indépendants’ inaugural show in 1885 (where he consistently showed until his death) to his partnership with Ambroise Vollard in 1902, and The Dream’s success in 1910 shortly before his death that year. These biographical details are, in fact, central to the interrogation of Rousseau’s place in art history. Even a cursory review of this wall makes plain that he operated within an established network of exhibitions and artists. Hardly an outsider, then, these details require one to immediately rethink Rousseau’s relegation to art history’s edges.

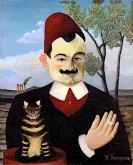

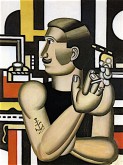

Turning from sa vie, the exploration into son oeuvre commenced with a survey of portraits by Rousseau and of Rousseau and others. In the decision to install his 1890 Myself, Portrait-Landscape in this first room, the curators lionized Rousseau as a great artist in the history of art—a role that he seems to welcome with his beret jauntily set atop his head and his palette and paintbrush in hand (fig. 3). To illustrate that he put his portrait-landscapes into discussion with past precedents, the artist’s Portrait de M. X (Pierre Loti) was placed beside a Renaissance portrait with which it bears some formal resemblance (fig. 4). Hung on the opposite side of M. X, could be seen Leger’s Le Mecanicien (The Mechanic) who, with similar nonchalance, brandishes a cigarette (fig. 5).

Throughout its ten rooms, comparisons such as this subtly illuminated connections between Rousseau and those before, but especially after him. These comparisons may have seemed simple to the trained eye—recollections of undergraduate art history courses with their compare-and-contrast exercises come to mind. Here, though, this organizational scheme showed that Rousseau should rightly be understood as significant to many artists, many periods and many movements.

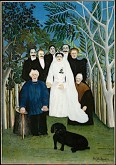

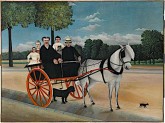

The curators effectively deployed this strategy to demonstrate Rousseau’s palpable influence, though on occasion, these comparisons could have been strengthened. In a room subtitled “Innocence Archaïque,” for instance, Rousseau’s The Wedding Party was hung alongside Maurice Denis’ sweet portrait of André Mellerio and family. This was an apt comparison, though one wonders whether, say, a traditional Mexican retablo painting of a wedding scene would have better articulated the exhibition’s interest in archaism (fig. 6). Junier’s Cart by Rousseau was effectively compared with Carlo Carrà’s The Carriage with their similarly painted horse-drawn carts (fig. 7). As the placard on the Italian Carrà elucidated, he took his inspiration from Rousseau as well as the Italian early Renaissance painter Giotto and new interpretations of the art of the Middle Ages that united “past and present time in a synchronic vision” (29). Carrà too conceptualized his artistic output as a meditation on time. Impossible though it may be to deny the visual similarities between their horse-drawn carts, Carrà has not executed his with the same esprit de joie (joyful spirit). Rousseau’s cart, accompanied by three dogs of incongruous size and breed, has a humorous effect. The mangiest canine companion has been lovingly tucked into the cart, leaving a silky black spaniel between its wheels while the tiniest of puppies stands in the path of the horse’s powerful hooves.

By setting Rousseau’s The Representatives of Foreign Powers Coming to Greet the Public as a Sign of Peace alongside Vallotton’s The Toast and the Italian Tullio Garbari’s The Intellectuals in the Cafe, the exhibition has prompted entirely new realizations about the former’s politics (fig. 8). Seeing Rousseau as a political artist is an important, and needed, intervention in the discourse (fig. 9). The Representatives records a celebration of the 1907 Peace Conference, which established modern rules of warfare. A follow-up to the 1899 Hague Conference, the Peace Conference convened in Paris in October 1907. Representatives from France’s colonies have here been shown clasping hands in a dance around the Place Maubert statue of the atheist Etienne Dolet, who, in the sixteenth century, vocally condemned the Catholic Inquisition and subsequently died at the stake. Erected in 1889 to commemorate the 1789 French Revolution and its foundation in free thought, the statue of Dolet stood as a secular martyr to those who believed, as Rousseau did, that rationalism should trump religious superstition.

On first glance, the painting may lend itself to the types of descriptions littering the Rousseau literature: an honest, flat scene by a naïf optimistically surveying world affairs from the sidelines. Yet The Representatives illustrates a potential paradox between Rousseau’s seeming technical simplicity and his political sophistication—a rich line of inquiry for future exhibitions. First, a painting such as this may reveal the complicated attempt on the artist’s part to shift his career in a direction potentially supported by state purchases.[4] (Despite those hopes, it ultimately entered Picasso’s collection.) Second, this painting put his art and politics into conversation with that of committed anarchist and socialist artists who exhibited alongside him at the Salon des Indépendants. And third, The Representatives further reflects his substantial work to tie his scene to earlier politically savvy paintings and painters of official pomp and circumstance, while also participating in current discourses around differences between painting and photography as artistic and documentary media.[5]

That Rousseau looked to secure commissions from the French state may imply that The Representatives would have been better compared with earlier official paintings such as Jacques-Louis David’s The Distribution of the Eagle Standards or, as the catalogue notes, Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Napoleon III Receiving the Ambassadors of Siam (fig. 10). Unfortunately, the Musée du Louvre’s or Musée du Luxembourg’s collections were not sourced to make these comparisons—collections that Rousseau, as both the exhibition and catalogue note, fastidiously studied and copied. Including paintings from those museums could have elaborated on the exhibition’s interest in historical antecedents for Rousseau’s archaism. It would have further illustrated one of the catalogue’s main arguments, that Rousseau was “neither self-taught nor anti-academic” (94).[6]

Not only does The Representatives resemble earlier painted records of parades and ceremonies. It alludes to newspaper engravings after photographs like those in L’Illustration that plastered these types of diplomatic events on its front page. However, Rousseau’s Phrygian-bonneted personification of France bestowing laurels upon these diplomats announces that this is a painterly representation of world affairs. More, the painting’s artistry, or lack thereof, appears in its details: its “union des peuples” resemble flat paper dolls-cum-diplomats; its circle of dancers similarly seem to be linked in a paper chain; and its republican ideals—paix (peace), travail (work), liberté (liberty), and fraternité (brotherhood)—have been inelegantly scrawled, with hyphens no less, onto the sides of planters in the foreground. What may be seen as a spontaneous union in the Place Maubert compares starkly, and, perhaps in a forecast of the First World War, bleakly, with the rigidly posed diplomats. We may read this scene as an overture to Rousseau’s anti-militarist, anti-monarchist, and ultimately, pacifist politics.[7]

From these dark green walls lined with portrait-landscapes and such better known paintings as The Representatives and The Football Players, the exhibition turned to Rousseau’s life-size portraits of women hung alongside monumental twentieth-century artist Paula Modersohn-Becker’s Portrait of Lee Hoetger on a Flowery Background (fig. 11). Installed in a circular room painted a cool mint, these portraits act as a transition to paintings of children. Surveying this room of Rousseau’s painted children, the oft-cited Baudelairean quip about artistic genius as childhood recaptured at will comes to mind.[8] Stout and stiff miniature adults, these tots, in the exhibition’s perspective, are at once “the most awkward, difficult and risky subjects for modern artists, and one of Rousseau’s greatest legacies is a vision of childhood as a prodigious and creative state of grace” (219). And these children certainly are awkward. They proudly display their toys but never play with them, and the subject in his commissioned Celebrate the Baby! resembles her wooden and cloth marionette in her stiff pose. Setting these children in nature, though, Rousseau may have meant to allude to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile and its proposal that children be educated through an immersion into nature.[9] Still, these Rousseau works seem anti-natural—an anti-naturalism especially made apparent through their comparison to Diego Rivera’s more playful Irene Estrella who presses a colorful wooden block to her lips.

Le Douanier Rousseau passed from these children in nature to two rooms organized around still-life and landscape. Subtitled “De Rerum naturum” (On the Nature of Things) in reference to the ancient Roman poem by the same name, the first room surveyed Rousseau’s still-lifes. More than pretty pictures of cut flowers and fruit, these paintings buttress the exhibition’s exploration of the contemplation of time. As a topic of artistic study, still-life underscores the ephemerality of time: in life, these flowers will wither, those fruits will shrivel and desiccate; in art, they remain forever fixed as flourishing and ripe. As the catalogue notes,

The state of spatiotemporal suspension on which his realism constantly draws freezes the image and shifts it outside real time. What we see is therefore like a still, a moment of life, or rather a reverie captured forever on canvas (27).

Descriptions of Rousseau’s still-lifes as “poetically lyrical” further elevate them to this realm of timelessness, as does their comparison to still-lifes by self-taught American artists held in the National Gallery, Washington, DC, collection and to those of Italian Magical Realist artist Antonio Donghi.

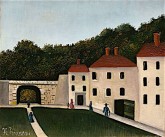

The second room dedicated to nature started its tour of Rousseau’s landscapes with Path in the Saint-Cloud Park (fig. 12). In its neat rows of trees, the Path led visitors’ eyes down the literal garden path, transporting them from the cut, dead nature of the still-lifes to cultivated suburban scenes. Inspired by postcards, photographs, and strolls around Paris, his landscapes hint at modernity’s transformation of the natural realm. Bi-planes teeter through the skies; trains cross iron bridges; and factories belch plumes of grey smoke into grey skies. Like the Neo- Impressionists to whom he has here been compared, Rousseau captured suburban modernity—Bellevue, La Passerelle de Passy, Alfortville, and the unspecified locale generically entitled House in the Suburbs—where casual strollers and fishermen live out their lives in an industrialized landscape. The catalogue praises these markers of modernity as “celebrating the technological achievements of the French [Third] Republic” combined with “the quintessential ordinariness of a Sunday afternoon in the country” (153). But where the Neo-Impressionists made suburban modernity overtly political, Rousseau has made that same suburban modernity wholly unremarkable. His is not, then, a modernity that disrupts the landscape, but one that has been integrated into it. In other instances, these markers of modernity are entirely absent. People Walking in the Park, for instance, portrays a gated garden as shut to the world outside its stone walls and beyond the thick bands of leafy green foliage (fig. 13).

Though Rousseau’s landscape paintings may seem somewhat banal when taken on their own, they have here provided an important point of departure for the more dramatic and familiar work that followed. The rest of the exhibition ventured into darker territory: the final rooms surveyed the horrors of war before mapping the artist’s most famous scenes of shadowy jungles. The visitor, then, made her way through suburban civilization, arrived at its cataclysmic breakdown, and finally emerged in Rousseau’s untamed wilderness.

Set in the center of a small room, making its grisly scene impossible to escape, War introduced late nineteenth-century European anxiety over increased militarization and, in France, compulsory conscription (fig. 14). Blood and sinew drip from the beaks of black crows that peck at soldiers’ nude or partially clothed carcasses. Death has here been depicted as a child carrying a sword and torch in hand, dressed in a tattered nightshirt and astride a horse. In a single leap of her horse’s suspended hooves, Death bounds across a landscape defoliated of the flora surveyed in the previous two rooms. With its tongue lolling limply from its mouth, Death’s horse and, by extension, War, poignantly foreshadows a more famous painted anti-war manifesto: Picasso’s Guernica, whose open-mouthed horse extends its dagger-like tongue in a piercingly silent scream of death.

Much was accomplished in this small room with this one painting. Rousseau becomes an archly anti-militarist and thus political artist, propelled outside suburbia and far beyond quaint flower pictures. The paintings and prints hung alongside War hint that Rousseau may have been inspired by imagery in the serial TSAR, Renaissance paintings like Paolo Uccello’s Saint George and the Dragon, and nineteenth-century academic paintings like William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s Egalité avant le mort (Equality in the Face of Death) of 1848. In turn, War may have inspired the Belgian James Ensor’s 1889 painting, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, shown writhing in a blaze of molten paint. War further prepared visitors to be welcomed to Rousseau’s jungles.

Channeling them through a corridor hung with The Dream and Surrealist paintings clearly indebted to him, Le Douanier Rousseau ended in a circular room dedicated to his jungle pictures (fig. 15). Visitors were there immersed in scenes of lions and tigers tearing into antelope and buffalo and other, more peaceful depictions of cuddly monkeys set in lush tropical forests (fig. 16). The exhibition walls’ palette of dark green and mint colors throughout was drawn from these jungle scenes as though they lurked all along in the backdrop of the exhibition. Wall texts were reduced to tombstone descriptions, and comparisons limited to a Delacroix and a Picasso discreetly tucked into a back corner, thereby permitting visitors to turn their attention exclusively to these paintings. Rousseau fully flowers here.

Though developed from extensive research—visits to the Jardin des Plantes (Botanical Gardens), taxidermy displays at the Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle (National Museum of Natural History), and children’s picture books—he claimed these scenes were taken from experience and memory. Adding to his own hagiography, he insisted that he had seen these exotic plants and wild animals decades before in Mexico, where he supposedly, but never really, served as part of the French forces charged with installing the Austrian Archduke Maximilian I on the Mexican throne. This last room acted as a climactic denouement—one that leaves us with the legendary Rousseau, painter of sauvage (savage) animal attacks depicted as frozen moments in time, albeit moments steadily developed from a lengthy evolution through his portrait-landscapes, portraits of women and children, scenes of still-lifes and the suburbs, and anti-war art.

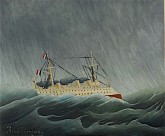

A truly beautiful and expertly organized exhibition, one of Le Douanier Rousseau’s real successes was how its own story rhythmically dips and crescendos, using key paintings to seamlessly transition between rooms and so between the chapters of Rousseau’s life and work. Ship in a Storm, for instance, the final painting in the rooms dedicated to still-life and landscape, illustrates the spectrum of Rousseau’s nature paintings from the sunnily lit, cheery Path on the opposite wall to this desolate shipwreck (fig. 17). Simultaneously, this scene of tempest-tossed natural disaster prepared visitors to experience the man-made disaster of War. Then, The Dream, with its quasi-Freudian nude reclined on a chaise-lounge and set in a distant forest, connects the exhibition’s nightmarish chapter on War to its conclusion with the jungle paintings (fig. 18).

Le Douanier Rousseau: L’innocence archaïque told its enchanting tale to art historians and the broader public alike. Its walls were punctuated with pithy quotes from artists, poets and Rousseau, attesting to his contributions to the history of art. For instance, poet Guillaume Apollinaire (whose concurrent exhibition could be toured at the nearby Musée de l’Orangerie), in a 1911 issue of L’Intransigeant, reported: “I have often seen him working, and so, I know with what care he has taken with all these details . . . he leaves nothing to chance, especially that which is essential.”[10] The same may be said for Le Douanier Rousseau’s curators. A richly rewarding exhibition for those who took the time to carefully study it, Le Douanier Rousseau: L’innocence archaïque provided a cool respite from Paris’s hot summer days and, ultimately, a welcome reprieve from typical treatments of the artist and his work. It was not to be missed.

Alexis Clark

Visiting Assistant Professor

Denison University

clarka2[at]denison.edu

[1] Roger Shattuck, William Rubin and Michel Hoog, Henri Rousseau, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1985), 28.

[2] See also Alfred Barr, Cubism and Abstract Art, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1936).

[3] As the catalogue makes evident, he was celebrated as a “precursor” and “initiator” by artists and the broader public in his own time; since then, however, he has been more ambivalently located by art historians as “out of step with his time, too far ahead or behind but certainly far removed from the approaches of his contemporaries and in any case impossible to compare, in its absolute originality, with the work of the above-mentioned great figures of the last century, the champions of modern art and innovation.”

[4] John House, “Henri Rousseau as an Academic” in Henri Rousseau: Jungles in Paris, exh. cat. (London: Tate, 2005).

[5] L’Illustration’s shift from older to newer technologies of reproduction has been discussed by Anne-Claude Ambroise-Rendu, “Du dessin du presse à la photographie, 1878–1914: Histoire d’une mutation technique et culturelle,” Revue d’histoire modern et contemporaine 39 (January–March 1992): 6–28.

[6] To the curators, that Rousseau actively consulted with Gérôme and Auguste Clément about his work and that he copied paintings in these two museums tempers longstanding descriptions of him as “self-taught.”

[7] These radical politics have been usefully explored elsewhere with regard to Rousseau’s connection to the Neo-Impressionist and anarchist Paul Signac and the circle of artists at the Salon des Independants. See Fae Brauer, “‘Le Corps Militaire’: Antimilitarism, Pacifism, Anarcho-Communism and ‘Le Douanier’ Rousseau’s La Guerre,” RIHA Journal 0048 (July 2012), accessed May 24, 2016, http://www.riha-journal.org/articles/2012/2012-jul-sep/special-issue-neo-impressionism/brauer-contesting-le-corps-militaire.

[8] Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” trans. Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon, 2001), 8. “The man of genius has sound nerves, while those of the child are weak. With the one, Reason has taken up a considerable position; with the other, Sensibility is almost the whole being. But genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at all. . . .”

[9] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile (1762).

[10] “Je l’ai vu souvent travailler et je sais quel souci il avait de tous les details . . . il abandonnait rien au hasard et rien surtout de l’essentiel.” Original text by Guillaume Apollinaire. Translation by the author.