The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Léonce Petit (1839–84) stands out in early comic-strip history for broadening the horizon of French-language cartooning, literally and figuratively. He introduced landscape art and a new attitude toward rural life to the Parisian illustrated press, breaking a lull in creativity that had followed the innovations in graphic storytelling introduced by Rodolphe Töpffer, Cham, and Gustave Doré in the 1830s to mid-50s period.[1] From 1863 on, Petit produced a wide range of cartoons that French nineteenth-century print culture globally designated as caricature, whether they featured distorted portraits or not. His most original and popular work appeared in Le Journal amusant: a series of genre scenes known as Les bonnes gens de province (The good people of our provinces) and comic strips published as Histoires campagnardes (country tales). He drew caricatures of celebrities and country-themed single-image cartoons for numerous illustrated periodicals of his time, including La Lune, L’Eclipse, Le Hanneton, Le Bouffon, Le Grelot, La Fronde, Le Monde illustré, and Paris-Caprice. Petit also illustrated about a dozen books and composed five illustrated novels and novellas of his own. For about 20 years, he gave his readers humorous snapshots and tales of provincial life and, through the turn of the twentieth century, remained the obligatory reference, in journalism as in fiction, in paysanneries—scenes of peasant life.

Nineteenth-century surveys of caricature provide little insight into his work, though it is possible to find numerous short articles on him in the contemporary press, mostly written by friends and acquaintances among men of letters. The first careful examination of his work appeared in David Kunzle’s The History of the Comic Strip: The Nineteenth Century (1990), which devotes an entire chapter to Petit.[2] Kunzle is primarily interested in the social history of Petit’s imagery, and much of his study interprets Petit’s images in the light of the cultural and political conditions of his time. Twenty-five years later, this remains the most extensive scholarship on the subject. In 2013, Mark McKinney provided the first in-depth analysis of Petit’s graphic novel Les mésaventures de M. Bêton (Misadventures of Mr. Stupid; 1868).[3] Antoine Sausverd’s repository of graphic literature Töpfferiana offers links to Petit’s works available in online collections.[4]

What I propose here is to trace Petit’s development as an artist by focusing on the formal aspects of his art. Commentators often compared Petit to Töpffer. While the analogy applies to some of Petit’s graphic narratives, it is almost irrelevant to others. References to the painter Jean-François Millet and the writer Honoré de Balzac also appear in more than one contemporary article on Petit. While neither comparison wholly characterizes his graphic narratives, it is true that the captioned genre scenes and comic strips he crafted are reminiscent of approaches to Realism that may be seen in contemporary painting and literature. His ethnographic-sociological perspective, a documentary-like approach to sketching out nature and rural environments, and an outlook on country folks that ran counter to established taste distinguish him from cartoonists of his time. Indeed, his cartoons of French country life strike a note of poetic Realism that is rare within the landscape of French nineteenth-century cartoon history.

Petit’s Career: A Mixed Success

Little biographical information on Léonce Petit is available today. What follows is gleaned from Kunzle’s research and nineteenth-century press snippets. Léonce Justin Alexandre Petit was born in an area of Brittany adjacent to Normandy, two regions that define his thematic horizon. The son of well-to-do parents of mixed social backgrounds, he received an excellent education and pursued law studies. He briefly worked as a registry office clerk in Auvergne but ultimately felt more attracted to art. He moved to Paris around 1863, thinking of starting out as a cartoonist in barrack-room humor of the kind he himself enjoyed in the weekly Journal amusant.[5] In the capital he found a welcoming community of artists and writers who held him in high esteem all his life. Friends appreciated him as “a man of letters and an erudite,”[6] as well as for his modesty, which came at the cost of financial success, according to journalist Francis Enne,[7] also a transplant from the composite patchwork of regions perceived from Paris as la province. Petit remained quite the country boy in Paris, with his marked Northwestern accent, unassuming lifestyle, and unpolished—some would say bohemian—personal appearance.[8] He was a bon vivant whose (sometimes naughty) singing enlivened banquets,[9] whose witticisms columnists occasionally reported in the press,[10] and whose name appears in at least half a dozen light-hearted poems published throughout the 1870s and 80s.[11] Friendships Petit formed early on prefigure as many facets of his lifework. In high school, he befriended future folklorist Paul Sébillot;[12] in Paris, he met Paul Arène, whose work with Alphonse Daudet was destined to epitomize regionalist Realism in French literature. Petit also fraternized with artists from the so-called Barbizon school of painting and studied landscape painting with two of them: Henri Harpignies and Augustin Feyen-Perrin.[13] A friend of Gustave Courbet’s, Champfleury, Realist writer and pioneer historian of popular arts and visual culture, whose works Petit reportedly admired, played a part in launching his career when he chose him as illustrator for a comedic short novel.

Aside from his press cartooning, Petit was also active as a painter of country scenes, on faience—a taste he acquired from Champfleury, Arène tells us[14]—and on canvas. From 1868 to his death, Petit submitted entries to the annual Paris Salon. To his dismay, however, they remained largely overlooked by critics, with the occasional mildly favorable review stemming from sympathy for the artist, it seems. An insightful and nuanced eulogy by journalist Montjoyeux perhaps best sums it up: “As a painter, he was not without talent, vigorous but heavy-handed, but his paintings did not receive the success he hoped for. The worst—and most legitimate—bitterness he felt, however, came from the semi-indifference that greeted his wonderful faience painting.”[15] Petit’s troubles with the Salon hit a peak in 1875, when his canvas was outright refused.[16] As we will see in more detail below, defenders in the press convincingly argued that the rejection was politically motivated, his subject deemed too controversial. Indeed known as an “uncompromising free thinker”[17] (destined to be buried in a religious ceremony against his wishes),[18] Petit at times alienated the most conservative among his readers.[19]

Nonetheless, the full-page drawings and the short stories in comic strips he published in the press garnered universal praise. In 1875, “too famous for any extended introduction,” according to art critic Mario Proth,[20] Petit was on his way to becoming the reference for paysanneries. Much of his cartoon art depicts crowds in open landscapes and rural streets; composition and detailed treatment of background reflect what he strove to achieve in painting, and compliments he only dreamt of for his work on canvas—“work of art,” “talent,” “originality,” “subtlety”—abound on Léonce Petit’s drawings. “Petit handled his countryside like [Jean-Baptiste] Corot and Millet,” Montjoyeux estimates.[21] Along with the painter of the Gleaners (1857), Petit promoted a caring and socially aware outlook on rural life that stemmed from personal experience.

Sadly, the second half of Léonce Petit’s relatively short career was marred by attacks of gout that increasingly interrupted his work, limited his mobility, and eventually left him completely paralyzed.[22] He passed away in 1884 at the age of forty-five, leaving a wife and infant daughter without any financial support.[23] His death came within a few years of the passing of three other caricaturistes that marked the century: Bertall (1820–82), Cham (1819–79), and Honoré Daumier (1808–79).

The French Töpffer Myth

From 1868 on, journalists regularly labeled Petit the “French Töpffer,” a view that Arène, Enne, and Frémine, at least, attempted to rectify upon his death.[24] As they note, no analogy to the Swiss master can subsume the various phases in Petit’s graphic style and approach to humor. Yet, as late as the turn of the nineteenth century, Emile Bayard, in a history of French caricature, still perpetuated the myth of Petit’s exclusive indebtedness to Töpffer:

One should not forget that Léonce Petit, as draughtsman, borrowed his style from Töpffer, the Genevan caricaturist whom we have mentioned, so that we shall not have to elaborate on originality of style in regard to the artist at hand. We already know that simple line-drawing, that wavering script-like sketching, without shading, without lighting, the clear silhouette, the scrawny outline. The author of Voyages en zigzag made it familiar to us.[25]

Convenient as it might be, the assessment has one sizeable flaw: it leaves out most of Léonce Petit’s work. Indeed, as modern scholarship has noted,[26] the analogy with Töpffer mainly suits Les mésaventures de M. Bêton, Petit’s only book-length graphic novel and a manifest Töpffer pastiche that sticks out in his career as unrepresentative of either his humor or his approach to storytelling. Petit’s genre scenes and down-to-earth anecdotes in comic-strip short stories bear no resemblance to Töpffer’s philosophical slapstick graphic novels, even though, as Thierry Smolderen, Professor at the École Européenne Supérieure de l’image d’Angoulème and author of The Origins of Comics (2014) remarks, the bucolic spirit of Petit’s peasant chronicles may have reminded some of Töpffer’s Voyages en zigzag short stories (1843, 1854).[27] Petit’s graphic style went through several phases, which coexisted at times, as was common among French cartoonists.

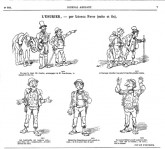

Töpffer’s contour drawing, which only occasionally features shading, has grown associated with a graphic-narrative paradigm known as “clear line” in today’s comic-strip lingo. Töpffer liked it for its clarity and narrative potential,[28] but contemporaries often defined line drawing as naïve and regressive—whether they held these qualities as endearing or undesirable. Théophile Gautier, for one, derided Töpffer’s cartoon style as “primitive” and likened it to Etruscan art.[29] Apparently unfamiliar with Töpffer, Montjoyeux draws a similar analogy to praise Petit’s graphics some forty years later. While Petit’s comic strip art (fig. 1) features zones of shading, his genre scenes (fig. 2) do not, resulting in a design that Montjoyeux describes as: “No shading, no texturing, just lines in the way of [John] Flaxman the Pre-Raphaelite, whose biblical, mythological, and Roman subjects evoke drawings on Etruscan vases. . . . That naiveté, seemingly emanating from a child, . . . denotes, on the contrary, accomplished experience.” Montjoyeux goes on to define an approach to cartooning that has little to do with Töpffer’s:

With such technique, more simple than easy, [Léonce Petit] achieved singular effects of power and depth in that long series of studies of peasants and farm life. . . . But what distinguishes him and sets him apart is his absolute mastery of drawing. His style differed from Gavarni’s and from Cham’s. Hidden under loose, oversized clothing, the anatomy of his peasant figures is perfect; there is the human body, in all its structure, its articulation, its muscles draped with fabric.[30]

Even among Töpffer’s most fervent admirers, few would claim mastery of anatomy as a characteristic of his cartoon art. Moreover, by the 1860s, various cartoonists internationally had used line drawing without necessarily mimicking Töpffer’s graphic style. Wilhelm Busch, a most influential figure in the development of the comic strip himself, also practiced uncluttered delineation of shapes; yet his graphic style bore no resemblance to Töpffer’s. A cursory look for practitioners of clear-line design in Second-Empire France alone brings up the likes of Jules Baric, Crafty, Gédéon, André Gill, Albert Humbert,[31] Alphonse Lévy, Loÿs, and G. Montbard, with variations in style that show that simplicity in line drawing does not necessarily equate with distortion of human traits. Ultimately, while the willing eye can detect an occasional figure resembling Töpffer’s and sketchy background zigzag shading in Petit’s drawings through the early 70s, such incidental channeling of the comic-strip pioneer far from defines his career as a whole. In spite of the occasional convergence, the analogy obscures as much as it elucidates.

Swarming Images

Closer observation shows that Petit is indebted to a handful of older graphic artists including Daumier and Gustave Doré—not the accomplished illustrator, but the budding artist nurtured by Charles Philipon in the late 40s. In 1849, the young Journal pour rire cartoonist added a new formula to his repertoire: half-page genre scenes featuring bird-eye’s views of crowds executed in fluid line drawing (fig. 3). These swarming images, to use Smolderen’s turn of phrase,[32] entertain the eye with the number of figures they feature and the diversity of their attitudes. Thematically, as Kunzle pinpoints, they are nothing but “a series of social scenes featuring large crowds and remarkably lacking in incident . . . the crowd for the sake of the crowd, which does nothing in particular or funny.”[33] As The History of the Comic Strip shows, the inspiration behind those drawings à la Where’s Waldo? more than likely emanated from a series of illustrations by Britain’s Richard Doyle featured in Punch at the same time.[34]

Gordon Norton Ray tells us that Doyle, also a precocious artist, was taught by his cartoonist father to keep “a pictorial record of London ceremonies and processions” that led him to develop “a special facility in drawing crowds, a gift that was to set the pattern for several of his later books.”[35] In 1847, to illustrate a mock old-English satirical ballad in Punch, Doyle took on a graphic style reminiscent of medieval woodcut.[36] That archaic slant quickly became his trademark. Over the following months, he produced multiple illustrations in naïve execution, faulty perspective, and captions with a Middle-English flavor. More often than not, they were overviews of scenes involving crowds—for instance, a derisive series of anachronistic images envisioning an ineffective French invasion of contemporary England. While these crowd scenes shed the initial historical graphic style, they kept the archaic spelling, turns of phrase, and typography, as well as what Kunzle defines as an unshaded, simplified outline approach to drawing. Thus Doyle devised the series Manners and Customs of ye Englyshe in 1849, a chronicle in 40 “half-page overviews of crowded popular gatherings and recreations”[37] with more polished clear-line figures and concern for perspectives, all represented from the same 45-degree angle.[38] In line with William Hogarth’s and George Cruikshank’s classic crowd scenes of previous generations, each plate came with a facetious companion text by Doyle himself. Doyle followed up in 1850 with a second Manners and Customs series of ten plates with no other text than their titles. The fact that Manners and Customs quickly became a regular last-page fixture in Punch magazine is an indication of its popularity. Within three months of that clear-line, swarming- image format’s début, Gustave Doré imported it to the Journal pour rire. He picked up the ludic challenge to place as many different yet compatible characters as possible inside a given frame with minimal redundancy, overlapping of figures, and blank space between them. Doré produced twenty such swarming images from 1849 to 1853, before giving up cartooning for loftier artistic horizons.

By 1857, the Journal pour rire had become Journal amusant and Baric picked up where Doré, now illustrator of Don Quixote, had left off. He adopted a similar clear-line style and even reprised a title once used by Doré, Etudes microscopiques (1862), which Baric alternated with Etudes physionomiques to underline the scope of his full-page swarming images as microcosms. Before Petit’s arrival to the Journal amusant, Baric, himself a native of France’s Western countryside, was the reigning specialist on the subject, and contemporaries subsequently often lumped him and Petit together as specialists in paysanneries. Baric’s star series Nos paysans, groups of single-panel, dialect-laden spoofs on country folks, appeared in the magazine for forty years. Its temporary title of Nos bons paysans in 1860 prefigures Les bonnes gens de province.

While Baric’s situation as Journal amusant’s country-life cartoonist certainly inspired Petit, the newcomer’s first published drawings in 1863–65 betray equal influence from Doré. This is especially true of Petit’s Vue prise dans la grande galerie des tableaux du Louvre (Snapshot of the great gallery of painting at the Louvre; 1865) that is a straightforward take on one of Doré’s subjects, albeit without the same swarming quality. Petit was still working out his own graphic identity. Many of his early 60s compositions were peopled with uniformly stocky, rotund peasants with short limbs, similar in inspiration to some found in early modern Flemish paintings. Baric produced some arguably undistinguished comic strips but excelled at filling up entire pages of crowd scenes (fig. 4). Up to the 1880s, he occasionally practiced the panoptic stylistic exercise. Petit’s swarming images, on the other hand (fig. 5), only served as a stepping-stone to his mature style. He refined each of their twin defining traits, the skillful configuration of figures and the narrative richness of their multiplicity, into the distinct formats of genre scenes and comic strips.

Maturation of a Cartooning Master

One unexpected aspect of Léonce Petit’s career as early bande dessinée master is that he came to it rather indirectly. In 1866, he diversified his cartooning with various formats of increasingly sequential images and with full-page caricatures for the weekly Hanneton. While he kept drawing panoptic crowd scenes, he began to fragment some of them into ensembles of smaller, captioned vignettes running over several pages. The first of such fractioned overviews, Le Pardon de Saint-Gildas-des-bois (The Saint-Gildas-des-bois penitential pilgrimage; 1866) is an account of an actual religious festival in 18 images of widely varying sizes (fig. 6). Executed in a looser, sketchier style close to Töpffer’s in parts—while his caricatures look as if drawn by a different artist altogether—Le Pardon is more farcical than customary Journal amusant lighthearted reportage. Petit’s approach plays up exoticism in the way the magazine’s illustrated features on foreign lands did. Motifs such as the “marchand de cheveux” (hair buyer) and autochthonous forms of courtship (“to win a belle’s affection with a steaming hot sausage and a nice grilled bacon rind,”)[39] rely on captions to convey meaning that the drawing does not make explicit. Spread over 6 pages and two issues of the Journal amusant, the ensemble is as much a sequence as it is a set of juxtaposed images on a central theme. Petit’s following sequence of captioned images, a few months later, La noce du garde-champêtre (The village policeman’s wedding; 1867), also unfolds along a minimal plot that is as much a pre-text as it is an actual storyline.

In contrast with such more or less accidental sequences, Petit made a clear move toward storytelling with a first novel, an illustrated comedy entitled Roman d'une cuisinière raconté par son sapeur (Story of a cook told by her sapper beau; 1866) that appeared a couple of weeks after Le Pardon. Friendly, short reviews welcomed this vernacular odyssey of a country conscript in Africa and his efforts to settle into domestic life back home. It got panned, however, by Émile Zola, himself working to break through as a novelist.[40] That rebuke did not deter Champfleury from offering Petit to illustrate a book version of Monsieur tringle, a humorous serial Champfleury had published in L’Illustration the previous year. Their text/image short story (1867) had the good fortune of receiving at least partial “thumbs up” from Zola.[41] That venture into traditional book illustration resulted in a comic strip of sorts: Le Journal amusant published a selection of Petit’s images as a condensed and autonomous version of the story. Fitted with captions adapted from Champfleury’s text, the sequential montage makes up a de facto graphic novelette that was published over three issues of the weekly in July and August. We do not know whether Petit, Philipon, or Champfleury came up with that editing work, but it must have played a part in Petit’s project of a book-length graphic narrative.

The graphic style Petit used outside of single-character caricature was evolving, alternatively shaded and clear-line; his characters gradually lost their bulkiness. By 1868 it took on a nervous energy and a tendency toward grimacing facial expressions. That Töpfferian turn was no coincidence: in March, Petit had set out to compose Les mésaventures de M. Bêton, a burlesque, graphic novel published in Le Hanneton over the last seventeen months of its existence.[42] With a protagonist physically resembling both Töpffer’s Mr. Crépin and Mr. Vieux Bois and, as McKinney remarks,[43] close in spirit to Mr. Cryptogame (1846),[44] M. Bêton is a narrative whose format, graphic style (captions in cursive included), comedy of repetition, and slapstick loaded with existential questions[45] reactivate the spirit behind Töpffer’s comedies. The Journal amusant capitalized on that kinship, all the while playing up the distinction. “As fine as Töpffer ever got,” one ad heralds, “with the added spice of a Parisian adventure that L. Petit so cleverly concocted.”[46] The tribute to Töpffer did not stop there: Petit sneaked two visual quotes from Mr. Vieux Bois (1826–39) into the first pages of Les quatorze travaux de Mathurin Piedagnel (The fourteen labors of Mathurin Lambfoot [1873]; fig. 7).[47] One motif in M. Bêton, on the other hand, possibly hints back to Doré: a bearded train mechanic wearing women’s clothing after losing his own attire. While the bearded fellow might very well be the archetype of the man in drag, the cultural specificity of the Northwestern-folks dress this one dons[48] singularly links him to Doré’s Hercules trying to pass himself off as a nanny to get close to Queen Omphale in Les travaux d’Hercule (fig. 8).[49] Petit revisited the device ten years later in Le banquet hippophagique (The horsemeat banquet) with a disgraced citizen hastily disguising as a maid to skip town.[50]

After M. Bêton’s foray into the comic strip, Petit branched out again, in 1869, to a satirical series of individual prints in lithographic chalk entitled Mœurs champêtres (Country mores). Small-town humorists hoping to make it big in Paris often embraced condescending clichés on “provincials.” The Alsatian Gustave Doré had done it; Baric had capitalized on it. Petit’s addition to his palette fell in line with Baric’s peasant scenes and with the punchline-cartoon form as a whole. Also published in the Journal amusant, Mœurs champêtres staged country people the usual way urbanites satirized them: parochial and equipped with thick regional accents and quasi-darwinian cupidity. One of the lithographs evoking a scene of merry drinking recycles a classic ethnotype of country-folk immigrants in Paris, a one-liner imported to visual culture through an 1841 Daumier cartoon, Ni hommes, ni femmes, tous Auvergnats! Fouchtra![51] Whatever compelled Petit to conform to established taste, his strength did not reside in such lampoon, nor in the illustrated gag format. He abandoned both after a couple of years. From 1872 on, his great œuvre de décentralisation[52] found a balance between two poles that Kunzle aptly defines as the “stasis of the single-scene format of the Bonnes Gens [and] the dynamic of the Histoires campagnardes.”[53]

Over 15 years, Petit composed around 200 Bonnes gens de province genre scenes supported by four or five lines of text and 50 short Histoires campagnardes averaging three installments of two to four pages each. Selections appeared in five hardcover albums between 1875 and 1884.[54] Petit’s panorama of country life stands out in several ways. Thematically, it holds attention for the kaleidoscopic breadth of its facets in a satirical press until then little interested in discriminating examinations of rurality. As a blend of images and words, Petit’s cartooning intersects with Realist culture across media, in a more narrative way than visual arts and in a more satirical way than literature, with, perhaps, the exception of Champfleury’s. Kunzle qualifies Petit’s work as unique within the era’s cultural spectrum for its Realism in portraying peasantry[55] and explores the thematic class-struggle dimension of that work.[56] I will confine myself to sketching out a general overview of Petit’s Realist approach to cartooning.

Realism in Cartooning

Bonnes Gens and Histoires fit within the segment of panoramic literature[57] that Charles Baudelaire’s 1857 essay “Quelques caricaturistes français” dubbed “caricature of manners” in regard to Daumier.[58] With their focus on everyday life and typical behaviors, societal surveys are a Realist genre by nature. Daumier’s outlook on his contemporaries concerned Paris and its immediate countryside. With due allowance for difference in corpus size (Daumier’s counts thousands of prints), Petit’s panorama picked up where the master of caricature’s left off and expanded that scope to the rest of France. With a simple mental switch from ville and bourgeois to village and provincial, passages from Baudelaire’s critique of Daumier’s art provide a fitting analogy to Petit’s approach to his subject matter:

Look through his work, and you will see parade before your eyes, in their fantastic and gripping reality, all that a great city contains of living monstrosities . . . every stupidity, every example of pride, every enthusiasm, every source of despair in the bourgeois’ life, nothing is missing. No one knows better than he has known and loved (in the manner of artists) the bourgeois, that last vestige of the Middle Ages, that gothic ruin that dies hard, that type at once banal and eccentric. Daumier has lived intimately with him, he has spied on him day and night, he has learned the secrets of his bedroom, he has become acquainted with his wife and children, he knows the shape of his nose and the structure of his head, he knows the spirit that animates his household from top to bottom. . . .[59] His caricature has a formidable breadth, but no rancor or bitterness. In all his work there is a fund of courtesy and bonhomie. . . . He has described what he has seen, and the result thus came about.[60]

Reviews and advertisements for Petit’s albums converged around notions of familiarity, observation, and bonhomie, a noun that contemporaries consistently applied to his wit. Journal amusant ads pointed up the genuineness of Petit’s “sketches made from real life,”[61] “generally composed from the author’s memories [and] collected by the fireplace from the very mouth of rustic storyteller”[62] to “capture the truest character of provincial life.”[63] Cultural clues in many of these texts—the narrative captions make even the individual plates concise visual/textual chronicles—denote them as set within the Brittany/Normandy region, but some of the situations they depict take place in a generic countryside. That global point of view on the province in a country where climates, cultures, and dialects differ greatly from one side to the next was a concession to Parisianism. Yet, each installment came grounded in authenticity that only personal experience could impart. The unprecedented variety of subjects these texts deploy grants them documentary value on ways of life that were already becoming archaic, as Montjoyeux recalled in 1884.[64]

Les quatorze travaux de Mathurin Piedagnel (1873), for instance, conveniently encapsulates an entire ethnographic paradigm within just a few pages. Desperate to earn the village bailiff’s daughter’s love, an idle youngster endeavors to make himself indispensable to her family. Overeager to please, he volunteers to accomplish a punishing series of labors for them: fishing for frogs, cutting wood, weeding a field, grinding pepper, delivering a calf, skinning a horse, shaving a dog, castrating piglets, helping a veterinary test a remedy, singing at mass, replacing the church steeple’s metal rooster, draining an outhouse, and supporting a departmental council candidate. Turning his campaigning into a boisterous demonstration, he angers local authorities and ends up in jail. Upon his release, discovering that his beloved has married the very officer who arrested him, he pledges to withdraw to the woods and become a charcoal burner. Among cultural markers that give the world Petit animates authentic Gallic flavor, processions (religious and otherwise) and drinking are recurrent motifs.

In contrast with the lively sequential Histoires, many Bonnes Gens de province tableaux are imbued with gentle irony. La boutique du savetier (The clog-maker's shop; 1873), for instance, represents a rectory servant enjoying special prestige in a cobbler’s humble dwelling, where her position on the social ladder gives her the opportunity to pontificate and receive VIP treatment (fig. 9). Poetic Realism permeates such portraits as La gardeuse d’oies (The goose girl; 1876): “Still too young for farm work but too old to be left idle, the girl has been promoted to goose herder. . . . Do not get the idea that the dog was given to her to help shepherd the feathered flock. Rather, he is a dog from the neighboring village who has become attached to the youngster and leaves his master’s home every day to keep her company.”[65] Besides typical snapshots of daily life, portraits, and colorful drama, Petit also offers an array of less conventional scenes. Titles like Bourgeois féodaux (Bourgeois landowners; 1872), L’archéologue en tournée (Archeologist’s survey; 1872), Les hurleurs de complainte (Murder-ballad singers; 1875), Les chercheurs de pain (Beggars’ new year wishes; 1876), Le peintre et les mendiants (The painter and the beggars; 1877), L’huissier en vélocipède (The bailiff’s velocipede; 1877), Le chameau (Camel; 1877), Noce de mendiants (Beggars’ wedding, 1879), and La rue aux chèvres (Goat street; 1879), give a sense of intimate connection with the world he paints. Such kinship imparts his satire with certain benevolence. That humor may include sarcasm and burlesque, but it targets injustice and narrow-mindedness, not people. Panoptic or intimist, self-standing or sequential, Léonce Petit’s scenes take place in a world where any population has its share of good and bad, sensible and short-sighted, ordinary and quirky individuals.

Petit’s perspective not only transcended hackneyed clichés but also eschewed idealization of rural life. The work that defines and glorifies the laboureur’s condition rarely comes up in these scenes; aside from livestock farming, depiction of agriculture occurs more as contextual element than as survival necessity. That is not to say, however, that stark realities of life are glossed over. Begging, for example, is one of Petit’s most recurrent tropes. Indeed, material considerations stand at the core of many plots, but they concern social relations rather than individual manpower, money and the circulation, rather than the production, of resources, in a cartoonish Balzacian perspective wrapped in earthy humor. La victoire de madame Boucarante (Madame Boucarante’s victory; 1876), for instance, rests on a dispute over the matter of whether a donkey’s droppings belong to the animal’s owner or to the street sweeper who pays yearly dues to enjoy the “fruits” of his labor as a commodity.

Illustrated magazines had long sanitized their pages from any scatological humor that sometimes tinted eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century caricature. Yet, Léonce Petit does not shy away from livening up some of his drawings with the occasional naturalistic detail of animal anatomy or behavior. In Aimable curiosité de la population de Crétigny-les-Gâteux à l’endroit des Beaux-Arts (Amiable curiosity of the Crétigny-les-Gâteux population toward the fine arts; 1868; re-titled “Les dessigneux” [Piktcher drawers]) in the 1879 Les bonnes gens de province album, a dog epitomizes the local population’s general incomprehension toward an unfortunate painter by shamelessly adding his own touch of color to his paintbox. Numerous prints detailing the plight of the landscape painter confronted by puzzled, inconsiderate, or outright hostile locals suggest a likely autobiographical vein.[66]

In the fashion that concurrently flourished in the Realist novel, speech is rendered “as is,” in all its vernacular phonetic or spelling corruption, and also in untranslated dialect. Among characters, even types come across within a literary Realist perspective. The cunning peasant invoking his wife’s resolve as bargaining technique in L’Usurier (The usurer; 1875) echoes tropes straight out of both Balzac’s Illusions perdues (Lost illusions; 1837) and Champfleury’s short story “Les Trouvailles de M. Bretoncel” (Mr. Bretoncel’s great find; 1865). Léonce Petit’s contribution to the immemorial miser type lies in a decomposition of movement highlighting his craftiness (fig. 10), three years before Eadward Muybridge’s first stop-motion studies of animal locomotion—a narrative device that only Nadar’s Vie publique et privée de Mossieu Réac (1849) had explored in comics.

One of the very few histoires campagnardes to feature the supernatural does so within a perspective that literature labels “magic realism.” Suddenly gifted with wit and eloquence, pig-herder Antoine Gorou finds himself arrested, suspected of subversion for discussing politics in an inn. Gorou’s understanding of the matter is clear: “Why was I arrested? Because I am a pauper. When big men with private income talk politics on the election trail, are they sent to prison?”[67] Petit’s take on inequalities in the justice system—like his involvement in the left-wing press[68] as a whole—were not always well received.[69]

According to Proth and journalist Charles Leroy, Petit’s entry to the 1874 Salon des Beaux-Arts, Candidat sur le champ de foire (Candidate at the fairground), received much favorable attention.[70] The next year, however, the jury refused his submission, a painting titled Entre deux gendarmes (Between two gendarmes), which Proth affirms attracted “a constantly renewed public” to the art dealer’s window that ended up showcasing it for two months afterward.[71] Both Proth and journalist Camille Pelletan suggested that its subject matter, conceivably subject to interpretation as an act of defiance against authority, caused it to be turned down, even though, in both writers’ opinions, Petit had not made it a political charge.[72] I have been unable to locate any reproduction of Petit’s painting so far, but two other versions of the scene give us clues about its author’s intent: Proth’s article includes a preliminary drawing of its central characters, and an earlier version of the entire scene exists as part of the Bonnes Gens de province series (fig. 11).

Entitled Emmené par les gendarmes (Under arrest; 1869), the plate depicts a despondent peasant handcuffed and taken away amid the jeers of some onlookers and the indifference of others. “Jean-Pierre does not pay his taxes,” the caption explains. “He is taken to prison. Alerted to the news, onlookers show wicked delight at their neighbor and mate’s misfortune. Canisy-les-Gâteux villagers have such a good heart!” The final sarcastic note that highlights the good folks’ Schadenfreude also distances the narrator’s feelings from it. The words neighbor and mate underline the lack of compassion in the face of the unfairness that the tableau suggests, and the pseudo-toponym of Canisy-les-Gâteux[73] is a judgment in itself. Stressing the general absence of empathy toward the accused is the surrounding animals’ unawareness of the situation, with the exception of a braying donkey and barking dog. We are left to ponder whether they are just following the pack or embody the narrator’s reprobation.

Without the resource of a caption, the preliminary study of the central group (fig. 12) nonetheless visually expresses sorrow for Jean-Pierre’s plight through a pair of children among the gang surrounding the gendarmes and their prisoner. While the dog in that vignette merely seems caught up in the party’s general movement, two small girls, the youngest in the group, bear expressions of distress; one of them even appears to touch one gendarme’s arm as if to plead with him. Contrary to the Bonnes gens version, the graphic style here is more academic than caricatural, and the lawmen are depicted with more dignity. Overall, Proth counts sixty characters in the final painting, about one third more than in the print. Among them he notes a couple of adults showing pity for Jean-Pierre—not the priest, however, a figure that was not part of the Bonnes Gens version. His absence of compassion may have contributed to hurting jury sensibilities. “Is it true that the true reason behind the rejection lies in certain details that might have offended moral order?” asks Pelletan. “If that is the case, moral order must be very delicate. I have seen the painting on rue de Rennes, where it is exposed and gathers many viewers. And I have looked for such terrible details in vain.”[74] Proth contends that the painting is “not a caricature. The artist did not dip his brush in bile nor did he handle it as a vengeful whip. He has observed and rendered his observation with wit, gentleness, and bonhomie.”[75]

Diverse manifestations of Realism as practiced by Courbet, Millet, Gustave Flaubert, and Baudelaire faced similar attacks during the Second Empire, and fine-art juries repeatedly kept at bay Daumier and Doré, whose fame as illustrators surpassed Petit’s. His œuvre, however, did not manage to overcome such resistance. Neither, for that matter, did his delicate, light-hearted faience painting, a colorful version of his cartoon art, touch the public the way his combinations of pictures and text did. The 1879 Salon, incidentally, elicited at least two references to Petit in the press that frame both an operative hierarchy of disciplines and his worth within one of those disciplines. Joris-Karl Huysmans’s L’Art moderne derides a painting by Jules Denneulin, whose “firemen and peasants look farcical. They belong to that low-class art that Mr. Léonce Petit professes in illustrated magazines.”[76] Another Salon review, in the new daily Gil Blas, uses Les Bonnes Gens to criticize a painting by Maurice Leloir. It argues that the painter’s satire of country folks’ incomprehension of art, with a peasant and a cow looking over a landscape-painter’s shoulder with equally perplexed looks, does not measure up to the cartoonist’s treatment of the same subject.[77] A similar critique might oppose Petit as Gendarmes cartoonist to Petit as Gendarmes painter.

Scapes in Scope

Les Bonnes Gens de province’s unconventional proportion of words and artwork grant them a special place in nineteenth-century Realism. Baudelaire’s comparison of caricaturists of the previous generation contrasts Daumier and Gavarni in the way image and text interact in their prints. Holding Daumier’s art in higher esteem, he estimates that the captions attached to it (famously due to Philipon) are dispensable. In Gavarni’s case, in contrast, “the best part . . . is in the caption, the drawing itself being unable to convey so much.”[78] Petit’s single images stand between these two models. Before him, words in French caricature of manners consisted in either a simple title or lines of dialogue. With a wider focus than just one or two protagonists, Petit introduced the third-person narration that befits simultaneous actions.

Early on in his career, his series of fairs, banquets, markets, festivals, and ceremonies, gradually exhausted crowd subjects lending themselves to swarming effects. The Bonnes Gens shed their farcical, stereotypical dimension for a subtler treatment of scenes. Concise captions developed into fuller narratives. Panoptic perspectives became more panoramic. Through increasingly detailed renditions of picturesque nature and architecture, they displayed landscapist aesthetics unexplored until then in French cartooning (fig. 13). In sharp contrast with the overcrowding of his earlier images, Petit’s sceneries, in their composition of rolling hills and detailed treatment of trees against vast expanses of sky (fig. 14), evoke the Barbizon school of painting.

Before Petit, backdrops in cartooning, sequential or not, often were symbolic or synthetic, more or less sketched out in a popular art focused mainly on characters. Detailed backgrounds were not unknown to the trade, but they remained dispensable elements of setting that no artist worked at infusing with atmosphere like Daumier. Daumier rendered nuances of urban life through incomparable shades of light and darkness but generally framed scenes tightly around protagonists. Léonce Petit’s panorama of daily life, in contrast, embraces the background as subject in itself, as demonstrated by the amount of space devoted to it on a given page. John Grand-Carteret, second French historian of caricature after Champfleury, argues that Petit

knows how to group figures with perfect skill, and . . . his backgrounds are always wonderfully executed. Pages of landscapes, architectural details or simple farmhouses are as many line-paintings that frame characters in the most picturesque of manners. All in all, Léonce Petit is a humorist with a sense of nature, staging his figures within a milieu, in their natural element.[79]

Although Grand-Carteret does not use the word naturalist, the idea permeates Petit’s graphic literature, sequential or not, at several levels. The way Arène saw the cartoonist’s Realism, “Léonce Petit wrote the familiar poem of a rustic life that Millet narrates as an epic.”[80]

Fraught with the heritage of the Barbizon painters, his studies of common people’s daily lives also came about right as Zola’s Rougon-Macquart cycle enunciated his study of societal ecosystems as a principle of modern literature. Since Les Bonnes Gens de province and Histoires campagnardes always stage different protagonists, the common denominator is their provincial setting; the cumulative effect brings the milieu into focus. While Petit’s hybrid fiction stands far from any scientific aim, and his bonhomie thwarts pessimism, his ethnographic/sociological perspective is naturalist in its interest for the milieu, like Zola’s cross sections of society. With less text than Doyle’s Manners and Customs of ye Englyshe but more than Gavarni’s Les gens de Paris, Petit’s ekphrasis focuses on situations and psychology but never describes the background, left to speak for itself, in more expanse of detail than ever. The non-linear deciphering of the image and the extended amount of information it carries grant it its own reading pace. Petit’s oversize panoramic images invest his storytelling with amplitude of breadth and visual loftiness previously unknown to the graphic narrative. When wide shots appear in Petit’s comic strips (fig. 15), they create a narrative switch of gears not unlike the extended visual descriptions in Balzac’s and Zola’s novels.

Etienne Carjat eulogized Petit as a “Balzac of the countryside.”[81] While the analogy might be overemphatic, Petit’s folkloric chronicles fit right in with Daudet and Arène’s poetic Realism deployed in the Chroniques provençales series of short stories (1866)—better known under its subsequent book title of Lettres de mon moulin (Letters from my windmill)—and the endearing outlook he casts on his colorful regional characters announces Marcel Pagnol’s fifty years later. Léonce Petit’s cartooning, however, does not only fit within his century’s quest for rendering the real. Its naturalist roots go much deeper into art history.

As the gnome-like peasant figures in some of Petit’s earliest publications suggest, the Bonnes Gens owe much to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish painting. Petit’s swarming village festivals, fairs, and weddings, his typical characters (drinkers in an inn, a barber at work, a village notary) and daily scenes (killing of the pig, market days) all hark back to Pieter Brueghel the Younger, the Tenierses, and Adriaen van Ostade. So does his taste for rustic interiors, idiosyncratic architecture, and shabby dwellings. Like the old masters, and contrary to most nineteenth-century cartoonists, Petit occasionally juiced up scenes of festivities with the detail of an intoxicated, urinating, vomiting, or passed-out guest, even though he mostly shied away from including the flirting and brawling that accompanied such behavior in the classic paintings. Nowhere does the Low Countries’ influence come across as strikingly as in a print that seems to synthesize two paintings by David Teniers the Younger (1610–90).

While it is impossible to know with certainty that Petit studied these paintings, or reproductions thereof, Petit’s La cible (1875) closely overlaps in subject and composition with two of Teniers’s studies of games of skill, The Archers (fig. 16) and Peasants Bowling in a Village Street (fig. 17). Petit’s image depicts a shotgun-shooting contest outside an inn (fig. 18). Subject matter presumably determines the scenes’ identical perspectives. A wide shot is required to hold the space between contestants and target, and a left-to-right orientation of characters serves the idea of movement across the frame. All images, however, are structured along similar horizontal and vertical lines formed by the width and length of the street, the disposition of the shooters and groups, buildings, trees, and distance from background. La cible appears to fuse both of Teniers’s compositions into one. All three feature a man holding a jug on the same side of the picture as the man relieving himself on the nearest wall, a few feet away from him and also in the same position relative to the shooter. Target, dog, bench, design of the background closest to the vanishing point—the similarities are so troubling that La cible looks like a preparatory sketch for either.

In an original composition, Petit refreshes the theme of the outdoors game of skill, a recurrent motif with Gavarni, Daumier, and Doré, among other nineteenth-century French illustrators. Petit’s Le jeu de quilles (fig. 19) structures a bowling game around a slightly off-center X-shaped axis with characters facing the viewer. Replete with alcohol-fueled attitudes, the print is close in spirit to Flemish genre scenes by Adriaen Brouwer, with a villager kissing a reluctant woman on the cheek, punches exchanged between two characters, and a drinker turned to a wall in an unequivocal position. Over its 200 daily-life scenes, the Bonnes gens de province series implies that little has changed over two centuries, in spite of its gallery of modern types like the sub-prefect, the archaeologist, and the photographer. Its transposition of such classic models of celebration of peasant life to nineteenth-century France de facto makes Léonce Petit an heir to early Renaissance and Baroque Netherlandish peasant painters. Indeed, it may be argued that he was just as indebted to Brueghel, Brouwer, and Van Ostade as he was to Daumier, Doré, and Doyle, and, ultimately, to Töpffer. In Paul Arène’s words, written a few weeks before his friend’s death, Petit was an “original artist who, throughout an abundant series of country scenes, started by looking for Töpffer and ended up finding Teniers. And Teniers would smile at such swarming cabarets, at those drinkers leaning on their elbows with faces and poses expressing the most straightforward bliss.”[82]

Even country folks themselves praised Léonce Petit’s talent at capturing the essence of rural life according to Montjoyeux, who reports, “although [Petit] saw them as ugly, peasants laughed along with him. I know a main canton town where the Journal amusant was awaited like the proverbial Messiah, not only by the notary who received it, but by all the locals, who passed it along among themselves for a week.”[83] With such ethnographic flair and Petit’s artistic heritage, one can only wonder what prompted Bayard in 1900 to argue that Petit’s peasants “do not feel the least bit real,” and that “the stylish nature that the artist shows us represents nothing beyond the sheet of paper.”[84] Kunzle deplores the fact that the nineteenth-century critical outlook on the comic strip was for the most part “woefully inadequate and downright wrong,” citing other critics’ failures to bring Léonce Petit’s “into intelligent focus,”[85] and one could extend that assessment to Bayard. It took over a century for the general public to consider artist/scholar Rodolphe Töpffer’s body of work as a whole and to recognize his sequential cartooning as an experiment in visual/verbal rhetoric. The twentieth century almost overlooked Petit, but his approach to cartooning is in phase with an issue at the core of today’s most recent considerations in comics studies.

Panoptic, Panoramic, and Sequential

With a pictorial oeuvre at the crossroads of caricature, naturalism in painting, and Realism in nineteenth-century French literature, Léonce Petit drew his own page in the history of Realism. Albeit largely unrecognized, his work is a landmark in French-language comic-strip history and in the history of cartooning as a whole, if only for its blend of panoramic, panoptic, and sequential. Separating Petit’s genre scenes and comic strips according to today’s prevailing sequential/non-sequential dichotomy in comics studies would be counterproductive. His contemporaries took them as one body of work, and, as such, Petit’s cartooning provides an example for Thierry Smolderen’s warnings against isolating the comic strip from its native ecosystem.

Indeed, the author of The Origins of Comics has challenged the field-forming consensus of the comic strip as intrinsically sequential. This is a bold move, considering that the comic strip largely owes its relatively new legitimacy as a domain of scholarly investigation to its definition as sequential art—in contrast with a nineteenth-century classification focused on graphic style and medium (caricature and the press). “More often than not,” Smolderen deplores, “a researcher working under the sequential art paradigm will identify the material that already conforms to the sequential art definition, and exclude or marginalize the material that does not.”[86] Smolderen posits the swarming composition, nonlinear by nature, as equally constitutive of the comic strip as is sequentiality. “The tradition of swarming images,” he writes, “includes Bosch, Brueghel, Jacques Callot, Hogarth, Cruikshank (among many others), and goes back at least to the illustrated bibles from the Middle Ages.”[87] Léonce Petit’s Histoires originated from swarming images and took several years to emerge fully as linear narratives. His first multi-image suites like Le Pardon de Saint-Gildas-des-bois; La noce du garde-champêtre; and Les bonnes gens de province (1867), which, ironically, ended up as a title for his single-image series, were not stories per se. Like Germany’s Franz von Pocci’s Der Staatshämorrhoidarius comic strips (1845), they mutated from a non-linear ensemble of satirical vignettes. To continue a Darwinian analogy, the evolution from paradigmatic to syntagmatic in Petit’s and von Pocci’s cartooning points to an inherent advantage of the comic strip over other graphic species, which, ultimately led it to dominate cartooning in the twentieth century. Indeed, it is difficult to repress the syntagmatic reflex that engages any analogy between two contiguous pictures into a chronological or causal relationship. This natural inclination of the mind carries the very DNA of storytelling, and, ultimately, of language itself.

I would like to thank Petra Chu for her generous feedback and editing work on this paper, which stemmed from a presentation at the 39th Nineteenth-Century French Studies Colloquium, University of Richmond, VA, October 24–27, 2013.

All translations are by the author unless otherwise indicated.

[1] See Patricia Mainardi, “The Invention of Comics,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 6, no. 1 (Spring 2007), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring07/the-invention-of-comics.

[2] David Kunzle, “Bourgeois versus Peasant: The “Histoires campagnardes of Léonce Petit, 1872–1882,” in The History of the Comic Strip, vol. 2, The Nineteenth Century (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1990), 147–74.

[3] Mark McKinney, “Les mésaventures de M. Bêton by Léonce Petit: Reflexivity and Satire in an Early French Comic Book Inspired by Rodolphe Töpffer,” International Journal of Comic Art 15, no. 1 (Spring 2013): 2–34.

[4] Antoine Sausverd, “Léonce Petit,” Töpfferiana, accessed July 19, 2013, http://www.topfferiana.fr/category/dessinateurs/leonce-petit/.

[5] Charles Frémine, “Léonce Petit,” Le Rappel, August 21, 1884, 2; and Paul Arène, “Le convoi du peintre,” Gil Blas, January 31, 1886, 1.

[6] Emile Bayard’s 1900 biographical brief borrowed the phrase verbatim from Petit’s friend Charles Frémine’s eulogy in the daily Le Rappel. All quotations, except from Kunzle and Smolderen, translated from the French.

[7] Francis Enne, “Léonce Petit,” Le Radical, August 27, 1884, 1.

[8] Montjoyeux [Jules Poignard], “Léonce Petit,” Le Gaulois, August 20, 1884, 1; Arène, “Le convoi du peintre,” 1; Arsène Alexandre, “Henri Pille,” Le Figaro, March 3, 1897, 1; and Charles Frémine, “Par les rues,” Le Rappel, October 19, 1897, 1.

[9] Maxime Rude, Tout Paris au café (Paris: Dreyfous, 1877), 145; Frémine, “Léonce Petit,” 2; Enne, “Léonce Petit,” 1; and Arène, “Le convoi du peintre,” 1.

[10] See, for instance, Jean Ciseaux, “Journaux et revues,” Gil Blas, September 6, 1884, 1; and Paul Arène, “Types qui s’en vont. L’homme qui travaillait au café,” Gil Blas, January 27, 1888, 1.

[11] See, for instance, Charles Frémine, “À Léonce Petit,” in Floréal (Paris: Lemerre, 1870), 91–92; Raoul Lafagette, “Le moineau et la perruche” (à Léonce Petit,) in Mélodies païennes (Paris: Le Chevalier, 1873), 113–17; Ernest d’Hervilly, “Le Salon de 1873,” La Renaissance, June 6, 1873, 154; Étienne Carjat, “La chanson de l’héritier,” in Artiste et citoyen: Poésies (Paris: Tresse, 1883), 63–67; Prosper Marius, “Sixain” (Au très chier souffreteux amy Léonce Petit, Légendier d’histouères campagnardes et pourtraicturier d’y-celles), in Ronces et gratte-culs (Paris: Lemonnyer, 1884), 87; and Auguste Barrois, “Au regretté Léonce Petit,” in Miettes de souvenirs: poésies diverses (Paris: Lemerre, 1888), 153.

[12] Kunzle, Nineteenth Century, 151.

[13] François Thiébault-Sisson, “La taverne de la rue Jacob,” Le Gaulois, March 14, 1887, 2.

[14] Arène, “Le convoi du peintre,” 1.

[15] Montjoyeux, “Léonce Petit,” 1.

[16] Camille Pelletan, “Le Salon de 1875,” Le Rappel, June 16, 1875, 2; Mario Proth, “Le Salon. Voyage au pays des peintres,” Journal pour tous, July 16, 1875, 637; and Mario Proth, “Le Salon des refusés,” Journal pour tous, July 23, 1875, 653–54.

[17] Arène, “Le convoi du peintre,” 1.

[18] “Obsèques de Léonce Petit,” Le Matin, August 21, 1884, 2; “Les on-dit,” Le Rappel, August 22, 1884, 2; and Faber, “Nouvelles du jour,” La Presse, August 22, 1884, 2.

[19] See Montjoyeux, “Léonce Petit,” 1.

[20] Proth, “Le Salon des refusés,” 654.

[21] Montjoyeux, “Léonce Petit,” 1.

[22] “Les on-dit,” Le Rappel, August, 5, 1883, 2; “Les on-dit,” Le Rappel, August, 6, 1883, 2: Frémine, “Léonce Petit,” 2; “Nécrologie,” Le Petit Parisien, August 21, 1884, 2; and Enne, “Léonce Petit,” 1.

[23] Enne, “Léonce Petit,” 1; Faber, “Nouvelles du jour,” 2; “Plats du jour,” Le Radical, August 24, 1884, 2; and Arène, “Le convoi du peintre,” 1.

[24] “Töpffer was a revelation to him. Those line drawings struck a chord with his simple and straightforward nature. No shadowing, no frills; only outlines. He had found his device, his style, and soon left Töpffer far behind. One can follow his progress in the Journal amusant, which published his first drawings. . . . Les Aventures de M. Tringle earned success but it is the Bonnes gens de province that fully reflect Léonce Petit’s heart and soul.” Frémine, “Léonce Petit, 2; “To be sure, as a draughtsman, Petit was one of the most skilled; he might have restricted himself to a single genre that, in the end, could feel monotonous: paysannerie; but such was his excellence in it that he is forgiven for not trying to vary his studies. Some have said, and wrongly so, that his work stemmed from Töpffer’s. On the contrary, Petit had quite a personal turn of mind, and that’s what gave his oeuvre so much value. The few comical albums he published in the manner of Töpffer, like M. Bêton, do not constitute real imitation” Enne, “Léonce Petit,” 1 [Author’s note: Actually, Petit published only one album in that style.]; “After a phase during which he imitated Töpffer, he quickly displayed his originality with sketches whose flavor of rustic innocence gathered much attention.” Paul Arène, “Léonce Petit,” Gil Blas, January 1, 1886, 1.

[25] Émile Bayard, La Caricature et les caricaturistes (Paris: Delagrave, 1900), 172. He was the eponymous son of the artist who drew the iconic Les Misérables portrait of Cosette holding a broom twice her size.

[26] See Kunzle, Nineteenth Century, 152–54, 174; and McKinney, “Mésaventures,” 3.

[27] Email to author, October 6, 2014.

[28] See, for instance, Rodolphe Töpffer, “Histoire de M. Jabot,” Bibliothèque universelle de Genève (Geneva: Cherbuliez, 1837), 9:334–37; Rodolphe Töpffer “Le marchand d’images,” Magasin Pittoresque 10 (October 1842): 338–39; and Rodolphe Töpffer, Essai de physiognomonie (Geneva: Schmidt, 1845), 1. All are reprinted in Thierry Groensteen and Benoît Peeters, Töpffer, L’invention de la bande dessinée (Paris: Hermann, 1994), 144–60; 161–65; 187.

[29] “Du Beau dans l’art,” Revue des deux mondes 19 (1847): 887–88.

[30] Montjoyeux, “Léonce Petit,” 1.

[31] “Töpffer’s influence may be even more obvious on an artist like Albert Humbert, whose name is linked to the history of the comic strip only through a few sequences spread out over periodicals.” Thierry Groensteen, “Naissance d’un art,” in Thierry Groensteen and Benoît Peeters, Töpffer: L’Invention de la bande dessinée (Paris: Hermann, 1994), 133.

[32] Thierry Smolderen, “Why the Brownies Are Important,” La Tribune, Coconino, accessed April 13, 2008, http://www.old-coconino.com/s_classics/pop_classic/brownies/

brow_eng.htm.

[33] Kunzle, Nineteenth Century,108.

[34] A notable case of feedback loop, given the fact that the sub-title to Punch was the “London Charivari,” Philipon’s first directorial venture. Nadar, who outright pirated some of them in La Revue comique in early 1849, later gave a hint about Doré’s source of inspiration by characterizing his “vast line drawings” as “English imports, endless pages that could wear out one’s admiration with so much wit, observation, finesse, and humor.” Nadar, “Lanterne magique des auteurs, journalists, peintres, musiciens, etc.,” Le Journal pour rire, April 23, 1852, 3.

[35] Gordon Norton Ray, The Illustrator and the Book in England from 1790 to 1914 (New York: Pierpont Morgan, 1976), 140.

[36] Richard Doyle, “King Montemolin and the Glory of Peter Borthwick,” Punch 12 (January-June, 1847): 51.

[37] Kunzle, Nineteenth Century, 323.

[38] Bird’s-eye Views of Society is the title Doyle gave his last 16-plate series on the subject in Cornhill Magazine (1861-62).

[39] Le Journal amusant, May 19, 1866, 3.

[40] Zola’s verdict in L’Événement was unequivocal: “I cannot believe,” he accused, “that the public ever wanted such a book, nor can I believe that anyone could have written it out of pleasure.” Émile Zola, “Livres d’aujourd’hui et de demain,” (1866), Œuvres complètes (Paris: Fasquelle, 1968), 555.

[41] He dubbed it a “grotesque tale that makes you roar with laughter.” Émile Zola, “Correspondance littéraire,” (1866), Œuvres, 548–49. While Petit’s illustrated edition was only one of three versions (a third, with vignettes by Evert van Vuyden appeared in 1889), it was destined to become popular enough to warrant an 1886 bibliophile edition.

[42] Kunzle, Nineteenth Century, 154.

[43] McKinney, “Les mésaventures de M. Bêton,” 6–21.

[44] Petit, Mésaventures, 6.

[45] Groensteen, “Naissance,” 133.

[46] Journal amusant, November 21, 1868, 8.

[47] Léonce Petit, Journal amusant, February 22, 1873, 2–3.

[48] Léonce Petit, Les mésaventures de M. Bêton (Paris: Lacroix, Verbhoeckhoven & Cie, 1868), 26–29.

[49] Gustave Doré, Les travaux d’Hercule (Paris: Aubert, 1847), 40–41.

[50] Journal amusant, March 16, 1878, 7.

[51] “Not men and women—just Auvergne natives! [Regional swearword]!” The joke refers to bacchanalia. However, Martellière, in L’intermédiaire des chercheurs et des curieux 56 (October 30, 1907): 654 traces the origin of the expression to a Seven-years’ War anecdote related to Auvergne pride in a military victory.

[52] John Grand-Carteret, Les Mœurs et la caricature en France (Paris: Librairie illustrée, 1888), 470.

[53] Kunzle, Nineteenth Century, 149.

[54] About 40% of the Bonnes Gens (1875, 1879, 1884) and roughly 20% of the Histoires (1877, 1883) were published as hardcover albums between 1875 and 1884.

[55] Kunzle, Nineteenth Century, 148, 172.

[56] His chapter on Petit is entitled “Bourgeois vs. Peasant.”

[57] That is the way we retrospectively view nineteenth-century literature of manners/overviews of society/physiologies, whether in words or in images, since Walter Benjamin introduced the expression. Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (1927–40), trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin (Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999), Q2, 6, p. 531.

[58] Charles Baudelaire, “Quelques caricaturistes français,” in Œuvres complètes de Charles Baudelaire, vol. 2, Curiosités esthétiques (Paris: Michel Lévy frères, 1868), 407, Gallica, accessed December 2, 2014, http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1073236b.

[59] Translation by Michele Hannoosh in Michele Hannoosh, Baudelaire and Caricature: From the Comic to an Art of Modernity (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1992), 146.

[60] Charles Baudelaire, Baudelaire: Selected Writings on Art & Artists, trans. P. E. Charvet (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 224.

[61] Advertisement for Léonce Petit, Les bonnes gens de province, Journal Amusant, June 26, 1875, 8.

[62] Advertisement for Léonce Petit, Histoires campagnarde, Journal Amusant, July 14, 1877, 8.

[63] Advertisement for Léonce Petit, Les bonnes gens de province, Journal Amusant, June 26, 1875, 8.

[64] Montjoyeux, “Petit,” 1.

[65] Petit, La gardeuse d’oies, Journal Amusant, September 16, 1876, 2.

[66] Such autobiographical vein clearly emerges in a couple of situations staging gout sufferers.

[67] Petit, Les Ambitions d’Antoine Gorou (suite et fin), Journal Amusant, July 3, 1875, 5.

[68] Most notably as illustrator for a series of irreverent and polarizing publications by his friend Elphège Boursin, which, under the Père Gérard label, revived the name of a 1790s revolutionary country almanac.

[69] For all its praise, Montjoyeux’s obituary for Petit also contrasts his feelings toward Petit: “Unfortunately, the merry caricaturist did not content himself with entertaining France’s beautiful countryside. His politics were detestable. Led by a cunning party, he practiced his art in Le Père Gérard, a pernicious publication . . . that was dangerous because of its good-natured appearance, and played a most active part in demoralizing our villages.” Montjoyeux, “Petit,” 1.

[70] Proth, “Le Salon des refusés,” 654; and Charles Leroy, “Bibliographie: Les Bonnes gens de Province, par Léonce Petit,” Le Tintamarre, July 11, 1875, 6.

[71] Proth, “Salon,” 654.

[72] Ibid.; and Camille Pelletan, “Le Salon de 1875,” Le Rappel, June 16, 1875, 2.

[73] “Soft in the head;” from the actual Normandy town of Canisy. The closest compromise Bonnes gens and Histoires made with the standard type of country lampoon lies in a handful of derisive names he gave imaginary townships (Canisy-les-gâteux; Saint-Marcellin-les-gorets [swines]; Crétinchon [moron]), but such farcicality is exceptional throughout his cartoons, which feature plenty of actual Northwestern locales: Lambale, Saint-Brieuc, Plélan, etc.

[74] Camille Pelletan, “Le Salon de 1875,” Le Rappel, June 16, 1875, 2.

[75] Proth, “Salon,” 654.

[76] Joris-Karl Huysmans, “Le Salon de 1879,” L'art moderne (Paris: Stock, 1903), 65.

[77] Paul de Katow, “Beaux arts,” Gil Blas, December 12, 1879, 2. The article also happens to blast paintings by Gustave Doré.

[78] Translated by Charvet, Baudelaire, 228.

[79] Grand-Carteret, Caricature, 395.

[80] Arène, “Le convoi du peintre,” 1.

[81] Kunzle, Nineteenth Century, 174.

[82] Arène, “Promenade au Salon,” La Nouvelle Revue, May-June 1884, 602.

[83] Montjoyeux, “Petit,” 1.

[84] Grand-Carteret, Caricature, 171.

[85] Kunzle, Nineteenth Century, 174.

[86] Thierry Smolderen, “A Chapter on Methodology,” supplement, SIGNs, Studies in Graphic Narratives 2, no. 1 (2011), S. 1–23, at 3.

[87] Smolderen, “Brownies Are Important.”