The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Ireland: Crossroads of Art and Design, 1690–1840

Art Institute of Chicago

March 17, 2015–June 21, 2015

Catalogue:

Ireland: Crossroads of Art and Design, 1690–1840.

William Laffan and Christopher Monkhouse, eds.

New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2015.

288 pp.; 366 color illus.; checklist of exhibition; bibliography; index.

$50 (cloth); $35 (paper)

ISBN: 978-0-300-21060-6 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-0-86559-272-8 (paper)

On the morning of St. Patrick’s Day 2015, the green-striped steps of the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) were filled with dignitaries from Ireland, City Hall, and local Irish organizations as well as an Irish piper to lead the crowd into the museum in honor of a new exhibition, Ireland: Crossroads of Art and Design, 1690–1840 (fig. 1). Chicago’s Irish roots date to the foundation of the city in the 1830s and continue to sustain a vibrant cultural and economic relationship with the Republic of Ireland today. It was hardly surprising then that the Art Institute undertook a major exhibition on the role of Ireland in art and design during the colonial period from 1690–1840. Curator Christopher Monkhouse initiated the concept of exploring Irish culture during that era, in part, as a way to fill a gap in a series of recent exhibitions on the time periods both before and after the colonial era.[1] Ireland: Crossroads of Art and Design, 1690–1840 also offers a much needed correction to the persistent public image of traditional Irish culture as quaint and unsophisticated. The American sources for this stereotypical vision of Ireland also were grounded in Chicago; the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 had treated visitors to a two-thirds scale replica of Blarney Castle and a series of faux-Irish cottages with equally faux Irish peasants (19). As curator William Laffan comments in his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, “This [AIC] exhibition of fine and decorative arts from 1690–1840 offers a rather different picture. It explores the arts in Ireland from the Battle of the Boyne, which resulted in victory for English, or Protestant, interest . . . to the eve of the Great Famine” (19). This was the period when Ireland’s cultural sovereignty was unrelentingly undermined by England’s political, economic, and physical presence. Laffan continues, “The exhibition acknowledges the inherent difficulty in singling out the Irish component of the material world of an island colonized by its nearest neighbor, with porous borders, a government that actively encouraged the settlement of Protestant craftsmen from continental Europe, and patrons who often preferred the work of non-native artists” (22). The social and political context of British colonial rule was a recurring theme throughout the exhibition, and as the viewer quickly realizes, it was also a significant part of what it meant to be Irish during this era.

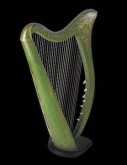

The exhibition design is based on the concept of an Irish-Georgian country house, inviting visitors to wander through portrait galleries, grand saloons, and libraries as well as galleries devoted to various types of decorative art displays (fig. 2). The entrance to the exhibition is clearly defined with a simplified neoclassical molding that remained constant throughout the sequence of galleries. Stepping through this entrance, the viewer is immediately presented with an exquisite Irish harp, Robert Fagan’s painting Portrait of a Lady as Hibernia (ca. 1801), and a prehistoric Giant Irish Elk (Megaloceros giganteus) skull with with ten-foot wide antlers (fig. 3). As Monkhouse explains, “The set [of elk antlers] serves as a symbolic welcome to visitors, evoking the eighteenth-century Irish tradition of mounting elk antlers in the entrance hall of a country house to suggest a family’s long held connection to the land” (17). This imposing prehistoric specimen, fortuitously available for the exhibition from the American College of Surgeons in Chicago, created a strikingly dramatic welcome to the exhibition. Coupled with the gentle sound of traditional Irish violin music in this space, the visitor could not have felt more at home.

In general, the exhibition focused on the city of Dublin and its surrounding countryside as the “second city of the British Empire” and its role as the center of Anglo-Irish culture. Galleries dedicated to categories such as portraiture, bookbinding, furniture, silver, glass, musical instruments, textiles, landscape painting, and architecture provided a thematic structure for exploring the ways in which Irish culture was produced. Because the time span of the show far exceeds the parameters of Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, the primary emphasis of this review is on materials from the long nineteenth century.

The other unifying theme of both the exhibition and the catalogue was the complicated and politically volatile question of Ireland’s status as a colony of Great Britain. William Laffan addresses this issue in depth in his introductory chapter “Colonial Ireland: Artistic Crossroads.” In response to the question of whether or not Georgian Ireland should be considered a colony, Laffan’s answer is “not quite” (20). The presence of Protestant English settlers in Ireland created the appearance that it was something slightly more than a colony, despite being a conquered nation without even a hint of sovereignty. The “Irish” Parliament in Dublin was run by English Protestants, and the viceroy in Dublin Castle was English. Catholics in Ireland had neither civil rights nor religious freedom; the Penal Laws imposed by the invading William of Orange in 1690 denied them the right to vote or stand for Parliament, and restricted Catholic religious practices through intimidation as well as law. Not surprisingly, rebellions against English control of Ireland occurred with regularity throughout the period of this exhibition and well into the twenty-first century.[2]

The apartheid system put into operation under the English was not significantly different from similar regimens that were imposed on British colonies in South Asia, Africa, and the Americas. Punitive taxes created hardship for native residents while financing the Crown’s military and economic endeavors, and the imposition of English culture was widespread. In Ireland, the English made efforts to “improve” the Irish, hoping that they would convert to Protestantism and embrace English values. In spite of what may have been a modicum of goodwill in some of these “improving” strategies, English settlers could not escape their own biases, including the perception that all Irish Catholics were somehow less than fully human. Nowhere is this more evident than in the design and art of the period; Anglo-Irish residents embraced continental influences from around the globe, including China, India, Japan, and Muslim North Africa, but they could not conceive of Celtic culture as a culturally legitimate resource. As Laffan notes, “The one national influence that, before 1840, was stubbornly resistant to incorporation into the decorative arts of Protestant Ireland was the native Gaelic tradition. Civility was equated with Englishness, and for most of the period, the material cultures of English and Gaelic Ireland did not cross-fertilize” (34). Understanding this frustratingly complicated political framework provides a foundation for placing Irish art and design of the period into the context of colonialism and the ongoing challenges of independence for Ireland.

The dramatic reception room at the opening of the exhibition is the centerpiece of a three-part gallery space. Unlike the typical layout of the AIC’s temporary exhibition space, this design allows visitors to begin their circuit through the metaphorical Anglo-Irish country house in either direction. To the right is a portrait gallery and to the left is a grand saloon, both spaces demarcated by ionic columns with flanking pilasters in black and white (fig. 4). This circulation pattern mimicked that of an eighteenth-century country house and clearly stated the design concept for the exhibition at the outset.

The portrait gallery adjacent to the reception gallery was dedicated to many eighteenth-century notables as well as an impressive collection of Thomas Frye’s mezzotints in their original pressed paper gold frames; these date to the early 1760s and consist of two series, the all male Life Size Heads and Ladies, Very Elegantly Attired in the Fashion, and in the Most Agreeable Attitudes (fig. 5). The nineteenth-century portraits in this gallery, however, were noteworthy for what they revealed about the influences of continental European art of this period. A group of three paintings related to the artists’ sons illustrated this in several ways (fig. 6). Matthew William Peters (1742–1814) demonstrated an early romantic sensibility in his Portrait of John William Peters, the Artist’s Son (1802), in which free brushwork and a surprisingly simple setting create an appealing image. Young Peters is shown as a budding scholar as he cradles a rather serious-looking book in his hands, but it is the sense of intimacy that his father has portrayed that captures the viewer’s attention. Nearly two decades later, Dublin-born Martin Archer Shee (1769–1850) portrayed his son in a casual, freely painted landscape. Here the stylistic approach might also be described as romantic, but it is more closely related to the French academic conventions of somewhat self-consciously posed children. The third of this group was Nathaniel Hone’s depiction of his son as The Spartan Boy, A Portrait of John Camillus Hone (ca. 1775). In spite of its early date, this painting feels considerably more romantic than Shee’s canvas; John Hone is shown as a slightly moody teenage boy silhouetted against a simplified background of stone and sky. His somewhat troubled gaze encourages the viewer to speculate about what he is thinking, and like the Peters’ portrait of his young son, to feel a curious intimacy with this individual.

It was Robert Richard Scanlan (1801–1876), however, whose painting The Blacksmith was most surprising (fig. 7). Although this work is dated only to the first half of the nineteenth century, the image of an Irish blacksmith resting from his labors discloses two significant characteristics: it is an image of a working man rather than a privileged—or comic—figure, and it is similar in spirit to the images of working class people found in the work of contemporary French painters like Philippe-Auguste Jeanron (1809–1877). Although Scanlan seems to have worked primarily as a genre painter catering to the Anglo-Irish market for images of horses, dogs, and anecdotal history, there is clear evidence in his watercolors that he was also concerned about the working poor in Ireland.[3] The blacksmith seated near his forge is shown in a monochromatic palette of browns and grays with all of his horseshoes pointing down—a comment perhaps on the state of the republican cause in Ireland?

The next gallery is also titled “Portraiture,” but here the thematic emphasis shifted to the performing arts and the wall color became a warm red (fig. 8). The molding around the entrance to this space reiterated the simplified Irish-Georgian motif of the entrance to the exhibition. With simple gold lettering against the black door surround, this architectural element not only announced a new theme, but also reminded the visitor of the country house design concept at every juncture along the circulation path.

Going to the theatre was an important social activity in cosmopolitan Dublin as it was in other European capitals of the time, but the best Irish playwrights seldom remained in their native land. With strict limitations on literary and theatrical production imposed by Dublin Castle, the majority of great Irish playwrights of this era—William Congreve, Oliver Goldsmith, Richard Brinsley Sheridan—made their way to better venues, ironically most often in London. The material that found acceptance in Dublin tended to be either Shakespeare’s plays or the English melodramas that emerged in the mid-1700s. Nonetheless, Henry Fuseli’s painting of Macbeth Consulting the Vision of the Armed Head (1793) offered a stunning glimpse of Shakespearean drama (fig. 9). Commissioned for James Woodmason’s Shakespeare Gallery in Dublin, Fuseli chose to portray the pivotal scene where Macbeth consults the three witches about his future, only to be given answers with deceptively hidden meanings.[4] The sharp contrast of light and dark, the ghostly head of the murdered Banquo, and the implacable faces of the three witches all contribute to the grim madness that ultimately catapults Macbeth to his own death. The popularity of theatre throughout Ireland is underscored in a nearby glass case where James Lewis’s Section of the Theatre for the City of Limerick is on display. This neoclassical design is very much in keeping with the crisply delineated architecture, then taught at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Lewis published his work in Original Designs in Architecture: Consisting of Plans, Elevations, and Sections for Villas, Mansions, Townhouses, etc. and a New Design for a Theatre in 1797 (fig. 10).

The visitor turns next to the theme of Dublin where the development of the city is explored in some detail (fig. 11). The dark and somewhat gloomy atmosphere of the previous gallery opened onto a large light blue colored gallery featuring an early survey of Dublin as well as several portraits by the American painter Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828) who received a number of commissions from prominent Dublin residents. The expansion of Dublin during this colonial period was quite dramatic. The population in 1685 was 45,000; by 1841, it was 254,000. Real estate development and commercial connections with the western ports of England and Scotland as well as the larger British Empire made the city second only to London in importance. It was during the same period, however, that the Irish diaspora began, first to other ports in Europe and then to Jamaica, Philadelphia, Boston, New York, and Chicago. By 1849 there would be 220,000 Irish immigrants arriving in the United States in just one year as a result of the Potato Famine and political oppression.

Equally fascinating, and equally eighteenth century in origin, was an adjacent display of bookbinding (figs. 12, 13). There are examples of a Bible printed by John Baskerville (1763) as well as Greek and Latin classics, but also small and elegant memorandum books from the Watson Bindery in Dublin. For bibliophiles everywhere, this was an opportunity to study Irish bookbinding in detail; for neophyte book lovers, an instructive video explained the techniques of the process.

At this point, the exhibition transitioned into a different type of display as the visitor entered the galleries titled “Made in Ireland” (fig. 14). The Irish-Georgian country house metaphor remained intact, but the emphasis in this multi-gallery section was on a variety of decorative arts. This section of galleries ran parallel to the grand entry sequence at the beginning of the exhibition, offering a contrast between the carefully designed public interiors of the aristocracy and the real world production of material culture. The first of these galleries included silver and ceramics, all in meticulously lit cases that stood out against the very dark charcoal color of the walls. Although the overwhelming majority of the silver here dates from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the silver chandelier hanging near a portrait of Laurence Nihell, Bishop of Kilfenora and Kilmacdaugh, deserves mention (figs. 15, 16). It is attributed to the local goldsmith Mark Fallon, who designed this and several other liturgical pieces for the Convent of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph in County Galway. The elegance, proportion and balance of this piece belie the notion that rural Ireland did not produce high quality goods.

The next three gallery spaces in the “Made in Ireland” sequence showcased textiles, glass, and musical instruments (figs. 17, 18). Of particular interest is the display of Irish glass, which is accompanied by recent scholarship on the history of Irish glassmaking from 1780–1835 (fig. 19). According to Peter Francis, author of the catalogue essay “The Enduring Myths of Irish Glass,” “...there has been a growing realization in recent years that the longstanding traditional narrative of Irish glass history—including even the notion of the Age of Exuberance itself—is not supported by historical facts” (187). Rather, it would appear that Irish glassmaking, like so much other design production in Ireland, was forced out of business by the same kind of restrictive English trade policies that wreaked havoc in the American colonies and eventually became contributing factors to the American Revolution. As Francis explains, the development of lead glass is now understood to have originated in The Netherlands in the 1660s and arrived in England in 1672 with two glassmakers who were fleeing the French military invasion. One of these craftsmen, the Italian John Odacio Formica, then moved on to Dublin where he continued to develop “crystalline glasses” (187). There is clear evidence of an international trade in lead crystal glassware up until 1698 when it ceased altogether because of England’s punitive Navigation Acts.[5] According to Francis, “. . . the effect was that Ireland’s glass exports were entirely extinguished for most of the following century” (188). Glassmakers responded to this dilemma by redefining their market, changing their production processes, and creating a new approach to glass design. The result was a simpler type of glassware, emphasizing form rather than decoration and utilizing a much lower lead content. The dark gray color that resulted from trace contaminants in the production process became a hallmark of its unique character. The market was no longer the middle class or Anglo-Irish aristocracy, but the Irish working class. It would appear that the concept of good design at an affordable price for everyone arrived in Ireland seventy years before William Morris stated the case in 1860s England. Sadly, the English tax measures imposed after 1800 “forced many Irish glass-houses to resort to smuggling in order to stay in business” (191). By 1835, almost all Irish glass production was closed; despite the quality of the work, even Waterford Glass had to shut it doors in 1851.[6]

The English restrictions on textile production were equally, if not even more severe than those on glass. Production of wool cloth for export, for example, was prohibited because it provided competition for the numerous English wool manufacturers. Instead, the Irish were encouraged to develop linen production, which subsequently became highly desirable in its own right. Most of the textile objects in the exhibition represented eighteenth-century tapestry production (typically in linen) as well as a selection of charming embroidered samplers. One of the few objects in the exhibition that related to the working class Irish was the needlework sampler book created by Dorothy Tyrrell in 1832. This portfolio of small scale samples was made when Tyrrell was a student at the Kildare Place Model School in Dublin, a school for training young women as elementary school teachers run by the Society for the Promotion of the Poor in Ireland. In contrast, the manufacturing side of the textile business was best illustrated by a large linen damask tablecloth design by Coulson’s Manufactory (ca. 1830) (fig. 20). Immediately adjacent to the tablecloth was a set of twelve didactic engravings by William Hincks showing the process of producing linen, from planting the flax to the finished textiles at the factory; these historical engravings remained quite effective in serving their original educational purpose in the twenty- first century.

Music certainly qualifies as one of Ireland’s most widely exported cultural traditions; the full scope of Irish design production would not be complete without the inclusion of musical instruments in the exhibition. Although references to musical instruments could be found in a variety of contexts throughout the show, the actual instruments were featured prominently in the “Made in Ireland” galleries where a cither viol, a kit/pochette (a small string instrument), an upright piano, and a portable harp took center stage (fig. 21). With the exception of the piano, portability is an important characteristic of many Irish instruments, in part because Irish music has historically functioned as much as a political tool as any weapon.[7]

The triangular-frame harp has been documented in Irish culture at least since the 1200s, but the harp as an instrument is recorded as having been used to accompany bardic poetry even earlier (fig. 22). Tom Dunne explores this theme in depth in his catalogue essay “Ireland’s Wild Harp: A Contested Symbol.” He notes that the harp has been used by both England and the opponents of English rule in Ireland since the 1700s. Today, it is an official emblem of the Republic of Ireland, used on its coinage and by numerous agencies of the state (119). The harp was first identified with a reform movement in the 1770s when a group of Anglo-Irish members of the Irish Parliament opposed the war against the American colonies. Government administrators responded to these calls for reform by establishing the chivalric Order of St. Patrick in 1783, apparently hoping to distract these reform-minded Irish peers with regalia. Harps featured prominently in this effort, typically illustrated with a nude winged female figure surmounted by an English crown, as in the Badge of the Grand Master of the Order of Saint Patrick (ca. 1850). The motto of this chivalric order, dictated by the state presumably, was Quis separabit (Who will separate us?). Six years after the creation of the Order of Saint Patrick, it became obvious that the government’s public relations strategy had failed with many of its intended recipients; a new reform organization known as the United Irishmen appropriated the winged nude harp image and changed the royal crown to a cap of liberty, not unlike that used during this same period in France. Several years later, during the armed uprising of 1798, the figure of liberty was again invoked in association with the harp, and a new slogan appeared on flags. In Gaelic, it read “Erin go bragh” (Ireland Forever) (122). John Egan’s Portable Harp (ca. 1820) represents a nineteenth-century adaptation of the traditional Irish harp, having gut strings rather than metal ones. This makes the instrument easier on the fingers, but it also creates a softer sound. The gold decoration includes shamrocks as well as acanthus leaves, a somewhat unusual (and botanically impossible) pairing.

The Furniture gallery opens off of the “Made in Ireland” spaces, serving as the turning point back into the Irish-Georgian country house metaphor (fig. 23). Representative pieces cover the scope of furniture that might have been found in a country house, ranging from tables, chairs, and desks to bookcases, game tables, and wine coolers, nearly all of it from the eighteenth century (fig. 24). The one exception is a grouping of two nineteenth-century pieces of furniture with a portrait of Lady Maria Conyngham by Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) (fig. 25). The earliest piece of furniture is the Cellerette (1821–25) designed by the cabinetmakers Mack, Williams and Gibton; it features not only the harp with the crown on it, but also four lions at the corners, presumably another reference to British royal authority. The design is adapted from the English cabinetmaker Thomas Sheraton’s pattern book, The Cabinet Dictionary (London, 1803). Finding this type of furniture design in Ireland was increasingly unusual after the Act of Union in 1800, which made all of Ireland a part of the United Kingdom; the Irish parliament was abolished and replaced with Irish representation at the English parliament in Westminster.[8] Mack, Williams and Gibton also produced the second piece of furniture on display, the Hall Bench from 1829/42. This particular design was originally created by the English architect James Wyatt (1746–1813) for Mount Kennedy, an Irish-Georgian estate in County Wicklow.[9] One slight alteration to the neoclassical design vocabulary appears to have been made by replacing the traditional Roman swags of garlands with a more rococo curving design around the central brass crest.

This grouping of early nineteenth-century furniture is crowned with a portrait of Lady Maria Conygham (ca. 1824–25) by Thomas Lawrence (fig. 26). The Irish connection here is that Lady Maria’s mother, Elizabeth, persuaded England’s Prince Regent (later King George IV) to create a peerage in Ireland for her husband in 1816. Several years later, Elizabeth became the king’s mistress. The portrait of Lady Maria suggests a young woman with a spritely sense of humor and an engaging self-confidence. Lawrence has characteristically captured her elegance and attention to the latest fashions in London.

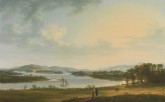

The warm coral walls of the furniture gallery offer a distinctive contrast to the sea green walls of the “Landscape” gallery as the visitor returns to the metaphorical public rooms of an Irish-Georgian country house (fig. 27). For the most part, the eighteenth-century landscapes on view here were very much in the tradition of Claude Lorraine, whose work was extravagantly popular with English aristocrats. One exception is the work of Thomas Roberts (1748–1778) whose early painting echoed the accepted conventions of French baroque compositions, but who had begun to embrace a more picturesque, or even romantic, sensibility before his death at age thirty. His depiction of Samuel Molyneux Madden’s estate in Lough Erne in 1771 was not only painted en plein air, but it also has a pendant painting that looks back on Molyneux Madden’s estate from a neighboring property. In the first image, Knock Ninney and Lough Erne from Bellisle, County Fermanagh, Ireland, the viewer shares the owner’s perspective from his home on Bellisle looking out over the wide vista of Lough Erne (fig. 28). The pendant painting reverses the view, showing what Sir Ralph Gore saw as he looked back towards Bellisle where his neighbor lived (fig. 29). Finola O’Kane points out that “. . . these pendant views transgressed the bound of estate portraiture in a way that ‘was both unprecedented in an Irish context and practically unknown in British art.’ When an estate portrait broke convention by being painted from within a neighbor’s property, it gave the patron, in Joseph Addison’s words, a new ‘kind of Property in everything he sees’ without the necessity of possession” (80). Clearly based on the ideas inherent in picturesque landscape design, Roberts nonetheless establishes an implicit sense of community in the neighborhood around Lough Erne. The fact that County Fermanagh lies in rural western Ireland may have meant that Anglo-Irish estate residents tended to band together as outsiders among the Catholic, Gaelic-speakers of the region. However, it is equally possible that the pendant paintings were intended to showcase the pleasures of country living for the increasing tourist traffic around scenic Lough Erne.

The “Landscape” gallery also presented the first hints of Irish immigration to the United States in a small hand-colored etching and aquatint of Daniel O’Connell’s home in County Kerry (fig. 30). O’Connell was an advocate for Catholic emancipation and repeal of the Union Act of 1800, but his fame rests on his prodigious skill at managing his own image as a reformer. According to William Laffan, O’Connell’s image “was the most widely circulated portrait in nineteenth-century Ireland. Some ten thousand plaster copies of Peter Turnerelli’s bust of O’Connell were cast . . . and his features decorate everything from plates and figurines to engravings, medals and handkerchiefs. It is not surprising that as a great manipulator of public opinion, he should have been adept at manufacturing and controlling his image” (54). Indeed, a Staffordshire figurine of O’Connell was displayed in the case adjacent to Robert Havell’s engraving, Derrynane Abbey, the Residence of Daniel O’Connell, Esquire, M. P. (ca. 1833). In the foreground stands a small trio of figures gazing out at the island Derrynane Abbey and the sea beyond. The male figure lifts his top hat as he gestures to the scene unfolding before them, commenting perhaps on that distant ship that is heading west to the cities of the United States across the Atlantic.[10]

The next country house ‘room’ is visually linked to the theme of landscape in its use of sea green walls, but the context in the “Desmesne” gallery explored the architecture of the country home in considerably more depth (fig. 31). In both paintings and architectural folios, the nature of the Anglo-Irish aesthetic is clearly expressed (fig. 32). The paintings, though mostly created in the eighteenth century, portray aristocratic English customs and beliefs: the love of dogs and horses; the indifference about acknowledging the full humanity of native peoples in British colonies, and the adoption of a neoclassical architectural language based on the work of John Vanbrugh and the Palladian circle around Lord Burlington. In the 1825 painting by George Nairn, the museum visitor bears witness to the stables of Robert FitzGerald, 19th Earl of Kildare at Carton, his estate in County Kildare (fig. 33). The lengthy title of the painting tells the story: The Interior of the Stables at Carton, County Kildare: A Liveried Groom, Lord Charles William FitzGerald, and His Sister, Lady Jane Seymour FitzGerald (fig. 34). To say that these pristinely clean stables are untouched by reality would be an understatement, and yet the canvas reflects the very real illusions of a privileged class.

The final gallery in the country house circuit is the “Saloon,” which is a gloriously grand, eighteenth-century space (fig. 35). The only nineteenth-century object in it is a pink crystal and brass chandelier from the Art Institute of Chicago’s collection that was a late addition to the installation (fig. 36). In a room full of tapestries and large-scale paintings as well as impressive silver serving pieces, the chandelier seemed to attract visitors’ attention first. Perhaps it simply added a necessary sparkle to the beautifully designed gallery.

Ireland: Crossroads of Art and Design, 1690–1840 was a challenging exhibition in many ways. It corrected the historical record on several fronts: First and foremost, it established definitively that Dublin was not a backwater, but second only to London in size and importance as a port city during this time period. Second, the exhibition presented new scholarship on the development of Irish glass-making, debunking the myth of an Age of Exuberance in lead crystal cut glass, and outlining some pathways for further systematic study. Likewise, the importance of musical instruments as design objects in their own right was reiterated; and the role of music as a powerful tool of cultural transformation was presented with an understanding of political implications, which are too often overlooked in art exhibitions. Ultimately, the exhibition significantly expanded the scope of art historical understanding about the art and design that was being created in Ireland from 1690 to 1840; equally important, it has suggested some new paths of investigation not only about Anglo-Irish culture, but also about the relationships between Ireland and continental European cultural trends. The excellent catalogue offers a thorough and thoughtful starting point for all of these topics. It is a comprehensive and carefully written publication that one hopes will become the foundation for the field of Irish studies in the future.

What was most difficult about this exhibition—and its greatest strength—was the unflinching willingness to depict Anglo-Irish culture as objectively as possible. While acknowledging in both the catalogue and the exhibition that politics are always present in Irish cultural history, there was no attempt to persuade the visitor to take sides. Historical events were presented straightforwardly, but not simplistically, and the frequently labyrinthine complexities of Ireland’s relationship with England was discussed with admirable detachment. At times, this felt exasperating because there are aspects of British colonialism that cannot be described in any charitable way. The point, however, was that Irish and English co-existence, if not actual friendship, produced an elegant, sophisticated culture that played a significant role from 1690 to 1840. As the organizers claimed, it turns out that Ireland actually was a crossroads of art and design in a number of important ways.

Janet Whitmore, Ph.D.

jwhitmore12[at]gmail.com

[1] The series began in 2012 with an exhibition, Rural Ireland: The Inside Story, at the McMullen Museum, Boston College, that examined the rural material culture of Ireland. In 2013, the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, presented Nobility and Newcomers in Renaissance Ireland, exploring the period immediately preceding that of the Art Institute show. A somewhat earlier exhibition at the Smart Museum, University of Chicago showed the period following the AIC exhibition with Imagining an Irish Past: The Celtic Revival, 1840–1940.

[2] The conflict between the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom’s province of Northern Ireland re-emerged violently in the last quarter of the twentieth century and the early years of the twenty-first century. Over the course of forty years of sporadic guerrilla warfare between Catholic Irish nationalists and Protestant Loyalist paramilitary groups, more than 3,500 people were killed and thousands were injured. The 1998 Good Friday Agreement brokered by the Republic of Ireland Taoiseach Bertie Ahern, President Bill Clinton, Senator George Mitchell, and British Prime Minister Tony Blair has led to a fragile peace. For an excellent summary of the progress on peaceful resolution, see Joshua Hammer, “In Northern Ireland, Getting Past the Troubles,” Smithsonian Magazine 39, no. 12, (2009): 64–73.

[3] Although the majority of Scanlan’s paintings deal with pleasant genre subjects that undoubtedly found a market among Anglo-Irish Protestants, his watercolors such as Man seated on a roadside with a cane (ca. 1855) or The Beggar (1835) indicate that he was interested in depicting the reality of the poor in Ireland. See artnet.com for images of Scanlan’s watercolors.

[4] Probably the most familiar of these responses from the three witches is that “Macbeth shall never vanquish'd be until/Great Birnam wood to high Dunsinane hill/Shall come against him” (4.1.87-90). Naturally, Macbeth’s foes camouflage themselves in the branches of trees from Birnam Wood in the last act, and the seemingly impossible prophecy comes true.

[5] John Odacio Formica became known as John Odasha in Dublin. The lead content of his glass was as high as 33%, which is comparable to the lead content of present-day Waterford crystal. There is only one intact goblet from this period, dating to ca. 1680 and now in a private collection in Australia. It is illustrated in the exhibition catalogue on p. 188. Fragments of similar glassware have been found at archaeological sites in Williamsburg, Virginia, and Port Royal, Jamaica, indicating that the Irish glassmakers were trading internationally during the late seventeenth century.

[6] It was not until 1951—a century later—that Waterford Glass was revived by modern manufacturers.

[7] It might be noted that an English court declared the bagpipe to be an “instrument of war” during the trial of James Reid after the Battle of Culloden in 1745. Although this claim seems to have been applied only in Reid’s case, the English Act of Proscription of 1747 did prohibit the wearing of tartans and Highland dress as well as the carrying of any type of weaponry regardless of size (a penknife, for example, was forbidden). The objective of this law was to obliterate as much as possible any sense of cultural identity among Scottish partisans.

In both Scotland and Ireland, music has long been a means of conveying coded messages among anti-English factions. The popular satirical song “The Wearing of the Green,” for example, has a much more serious version, known as “The Rising of the Moon,” which describes the guerrilla strategies used in the uprising of 1798. More recently, Tommy Makem’s 1967 song, “Four Green Fields” might be taken only as a paean to the Irish countryside if the listener did not understand the context of Ulster as a part of Ireland. For background on this topic, see the Irish Traditional Music Archive (Taisce Cheol Dúchais Éireann) at http://www.itma.ie. See also William Cole, ed., Folk Songs of England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1961).

[8] This arrangement was made in response to the Irish rebellion of 1798, which brought the question of Ireland’s colonial status to the attention of the British leadership under Prime Minister William Pitt. It was hoped that adding Ireland to the union would prevent continued strife, although that would not prove to be an accurate assessment. The Republic of Ireland finally gained its freedom from British rule in 1921—with the exception of the northernmost six counties of Ulster, which remain part of the United Kingdom today.

[9] For a fuller discussion of the history of James Wyatt’s design, and its subsequent dissemination in Ireland, see Christopher Monkhouse, “War, Politics, and the Diaspora of Irish Art and Design,” The Magazine Antiques, April 1, 2015 http://www.themagazineantiques.com/articles/monkhouse-irish-art/.

[10] Immigration to the US began to increase in the 1830s when Irish men left their homeland to work on the Erie Canal, and when that was finished, to move further west to Chicago to dig the Illinois and Michigan canal connecting the Great Lakes with the Mississippi River in the 1830s. Just one year after Havell’s engraving was completed, the City of Chicago would be officially established with a thriving population of Irish immigrants already in residence.