The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

¿Qué mayor venganza pudo jamás cumplirse en los destinos históricos de nuestro pueblo, en favor de la raza agraviada, que la lenta pero segura infusión corrosiva de todos sus vicios y abyecciones en lo más interno del organismo social?

What greater vengeance could have ever taken place in the historic destinies of our people, in favor of the battered race, than the slow but sure corrosive infusion of all its vices and abjections into the most internal sectors of our social organism?

—Dr. Benjamin de Céspedes, La prostitución en la ciudad de La Habana (1888).[1]

Introduction

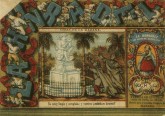

During the early 1860s, Havana’s tobacco manufacturers began packaging cigarettes using color-illustrated papers known as marquillas cigarreras.[2] For tobacco entrepreneurs, newly available chromolithographic technologies offered a cost-effective opportunity to package, brand, and advertise their products in an increasingly competitive domestic market. Housing twenty to twenty five units, the marquillas accompanied the widespread consumption of cigarettes throughout middle and late nineteenth-century Cuba. Particularly in Havana, the island’s largest urban center and home of the tobacco manufacturing industry, the marquillas enjoyed the viewership of large audiences. The small chromolithographic papers, approximately 12 x 8.5 cm in size, targeted a variety of consumers through a wide range of aesthetically pleasing designs combining text and image in eye-catching saturated colors. The juxtaposition of textual and visual signs not only allowed for the inclusion of logos, company credentials, and business addresses, but also gave life to humoristic narratives that sought to communicate a set of moral standards to the smoking public. This is particularly evident in marquillas depicting salacious jokes centered on the local costumbrista stock figure of the mulata (the female offspring of a white man and a black or mulatto woman) and her interactions with white men throughout the city of Havana.[3]

In this article, I evaluate the marquillas as circulating objects of material culture, which used a mechanism of satirical humor known as choteo in order to advertise cigarettes, and also to condemn illicit sexual encounters between white men and mulatto women. Through close analysis of five marquillas, I bring to light the ways in which this form of humor functioned as a double entendre. On the one hand, salacious jokes featuring sexually available mulatas enticed men to buy cigarettes. On the other, the jokes seek to ridicule white male desire for women of color by placing white men pursuing mulatas in dangerous or embarrassing situations.[4] Finally, my objective is to show how through the marquillas, tobacco manufacturers participated in state-wide initiatives aiming to reform civic education and social hygiene in a city where spatial borders and populations were in constant flux during the middle to late nineteenth century.

The marquillas’ treatment of the mulata has been previously studied in relationship to the emergence of Cuban nationalism. Alison Fraunhar has argued that the marquillas can be seen as “sites for the production and dissemination of national identity,”[5] where the mulata appears as an “ambivalent” figure, simultaneously operating as an “icon of imperial desire” and a “sign for Cubanidad” (Cuban-ness, that which is Cuban).[6] Madeline Cámara Betancourt calls the mulata a “truncated symbol of nationalism,”[7] while Vera Kutzinski denominates her as “a symbolic container for all the tricky questions about how race, gender, and sexuality inflect the power relations that obtain in colonial and post-colonial Cuba.”[8] However, by approaching the marquillas’ depictions of the mulata as remnants of a “Cuban” national character, the scholarship of Fraunhar, Betancourt, and Kutzinski has overlooked the local implications associated with the production and distribution of these images. After all, the marquillas were a product of Havana, and their portrayal of Cuban society often reflected a preoccupation with life in the capital city.[9] My study examines those prints—the ones that present Havana as a city filled with lust, interracial sex, and public indecency. In order to unveil the interlacing relationships between the marquillas and the city, I pay close attention to the interactions among print, industry, and urban reform in nineteenth-century Havana.

This article takes as main objects of study five marquillas produced by the Para Usted cigarette factory. The prints belong to two different moments of production. Three were printed individually; that is, not organized in a series, and two belonged to a series labeled “Historia Mulata”.[10] By looking at these prints individually, I depart from the way marquillas are generally studied: as consecutive narratives such as La Charanga de Villergas’s Vida y muerte de la mulata (Life and death of the mulata; fifteen prints). Looking at these prints as singular ephemeral objects that circulated independently corresponds to the way nineteenth-century smokers would have interacted with the images. Unless they were looking at a collector’s album, viewers would not have encountered a composite series of marquillas at once, but rather single-leaf prints.

Printing and Using the Marquillas

Little is known about Para Usted, the cigarette manufacturer that either printed or commissioned the five marquillas studied in this article, and even less about the artists, illustrators, or print shops involved in the marquillas’ production. According to Antonio de Gordo y Acosta, Para Usted was founded in 1850 by José Maria Guerediaga, and at some point during the decade changed hands to Eduardo Guilló, whose name appears as proprietor of the firm in the marquillas, and as a “cigar manufacturer” in The Third Biennial Directory of the Tobacco Trade (1877).[11] The numerous marquillas found today in collection records indicate that the company’s lithographic production was widely disseminated and sought after, perhaps due to the skillful execution of the images marked by great attention to detail.[12] Nevertheless, there are travel accounts detailing the manufacturing process of cigarettes and their accompanying marquillas as it took place in one of Para Usted’s competitor’s establishments and model for the industry: La Honradez.

The nineteenth-century industrial production of cigarettes was a modern spectacle of its own. So narrates Union Army veteran and travel writer Samuel Hazard who visited La Honradez sometime in 1866 or 1867.[13] Earlier in the decade, the firm’s employment of gas, electric, and steam-powered machinery had secured it international acclaim as Cuba’s largest and most efficient cigarette factory.[14] The successful consolidation of these production technologies, coupled with 300 in-house employees and over a thousand freelance workers who rolled cigarettes in their spare time for extra income, allowed La Honradez to put out an average of 2.5 million cigarettes a day.[15] These “fragrant paper cigars,” as Hazard informs us, were packaged in “very rich envelopes, possessing some two to three thousand patterns.”[16] The “envelopes,” marquillas cigarerras, were printed in situ by the firm’s state-of-the-art print shop, which, in order to package the factory’s daily production into packets of twenty four and twenty five, generated an average of 105,500 printed wrappers, 11,722 in color.[17] Packaged in their elaborate papers, the cigarettes made their way into street bodegas, entertainment venues, and commercial establishments, and from there they traveled to the homes, pockets, and purses of their consumers.[18]

At the time of Hazard’s visit, the burning smoke of tobacco was an inescapable sign of mass consumer culture. Struck by the indiscriminate consumption of cigars and particularly cigarettes, Hazard noted: “Wherever one goes in Cuba, the cigarette meets him at every turn, even more so than the cigar; for, in cars, between the acts of the opera house, in the mouths of pretty women, between the courses of the dinner, and even, I might say, at the very portals of the church-door, one finds the delicate, fragrant paper cigar.”[19] Hazard’s observation suggests that in urban centers such as Havana, cigarette smoking was ubiquitous and, as we now realize, closely associated with the arrival of modernity and the onset of mass consumer culture.[20]

The targeted consumers of chromolithographic marquillas consisted of Havana’s bourgeoisie and print aficionados. Alejandro Tapia y Rivera (1826–82), whose detailed account of La Honradez’s manufacturing process was published by the company in 1865, referred to the papers printed using the chromolithographic press as “cajetillas de lujo” (luxury packs), while those printed in the firm’s typographic office were designated as “cajetillas comunes” (common packs).[21] The division between a “luxury” and “common” product most likely dictated the price of the cigarette pack. Luxury packages (color illustrated) provided an added value to the cigarettes by using newly available chromolithographic technologies. As a more expensive commodity, the colored-printed marquillas targeted the middle- and upper-class consumer. The vast thematic range of the “luxury” packs suggests that they were geared to a diverse smoking public. While bucolic landscapes, classical imagery, and military portraits pleased the conservative smoker, flora and fauna appealed to the naturalist, embroidery patterns to the housewife, and picturesque scenes of everyday life attracted those interested in popular culture.

The current form of the marquillas: straightened out, sometimes trimmed, and pasted into collector’s albums or commercial trademark registers during the early decades of their production, obscures the ways in which these objects were used by their consumer. The absence of a marquilla in its original state has led scholars to believe that the object functioned as a cylindrical wrap that held cigarettes by tightly compressing them as a “bundle.” If this were the case, the wrapper would have lost its functionality after the first cigarette was subtracted and the pressure removed. This interpretation was derived from a self-referential marquilla entitled La cajetilla bocoy (The barrel-pack; fig. 1), in which three children push a bundle of cigarettes in the form of a barrel.[22] If one is to look closely at the center of the “barrel pack,” one will see the company’s logo, consisting of a blindfolded figure of justice, also seen in the emblema or trademark found on the right side of the print. It is clear that the marquilla is representing itself, but what is questionable is the open cylindrical shape. In the “barrel pack” bundle, the logo extends through the entire picture plain omitting the orla, or the decorative outer register of the actual marquilla where on top, a cigar bonfire has broken out, and on the left, a boy performs a military gait while holding a cigar as a substitute for a rifle. The orla is not visible in the miniature because it was most likely folded toward the inside in order to provide a bottom housing structure that prevented the cigarettes from falling. In his visit to La Honradez, where the barrel-pack marquilla was printed, Hazard described the packaging of cigarettes as “envelopes,” suggesting the existence of a bottom structure. Moreover, Hazard’s sketch (fig. 2) illustrates how the marquilla was folded at its lower end in order to provide a sitting base for the wrapped cigarettes.

As illustrated containers, the marquillas enjoyed the repeated viewership of the smoker. Hazard reminds us how cigarettes were usually carried and shared: “It is quite the proper thing to do, if you happen to be with the ladies in the railroad car, to present your cajilla of cigarettes to them.”[23] Hazard italicized cajilla as an indicator of a local Spanish term referring to a small box. Perhaps the North American was referring to cajetilla, the common term for cigarette pack as used by La Honradez in “La cajetilla bocoy.” If the marquillas functioned in a similar manner to cigarette soft packs today, the act of drawing a cigarette from its wrappers, whether for individual or shared consumption, required tactile and visual contact with the image. Moreover, if they were presented as a courtesy offer to a stranger of the opposite sex, who in turn proceeded to draw a unit out for him or herself, the marquillas not only shared the viewership of both parties, but also mediated the interaction between them. It is the portrayal of these very same interactions that is further complicated by the inclusion of the mulata in the marquillas. However, representations of the mulata were not unique to the cigarette wrappers. As the next section will discuss, her figure often appeared in Cuban costumbrista literary and visual works.

La Mulata de Rumbo

Para Usted’s marquillas employed a very similar pictorial vocabulary to that of costumbrismo—the Hispanic genre in nineteenth-century literature and visual culture that focuses on scenes and types of everyday life.[24] Costumbrismo arrived in Cuba via Spanish literary trends during the early nineteenth century. Costumbrista artists and writers sought to represent a national character using traditional “types” of people, their customs, and costumes.[25] Within the representation of Cuban types, the mulata entered literary circles fairly early. Most notably, she starred in Cirilio Villaverde’s canonic novel, Cecilia Valdés, published as a short story in Havana in 1839, and in its present form as a novel in New York in 1882. Regardless of her early debut, the mulata’s African roots prevented her inclusion in the island’s first costumbrista album, Los cubanos pintados por sí mismo (1852), in which the island’s population is depicted as exclusively white.[26]

The second album, Tipos y costumbres de la Isla de Cuba (1881), presents a different scenario.[27] In this publication, the authors seem increasingly interested in Afro-Cubans. Among the types included in the publication the mulata enjoyed great popularity. She appears as a protagonist in two short stories, “La mulata de rumbo” and “Una chino, una mulata y unas ranas,” and as the girlfriend of a tobacco worker in “El tabaquero.” Francisco de Paula Gelabert’s short story “La mulata de rumbo” appears in combination with a photolithograph by Victor Patricio Landaluze with the same title (fig. 3). Landaluze’s print depicts a woman of dark complexion standing alone in an unidentified setting. Among the clues identifying the mulata’s costumbrista “character” is her stance. She tilts her hips toward the viewer, thus accentuating the curve between her lower back and waist. Her coquettish pose is emphasized by the sassy hand gestures, one resting on her hip, the other holding a stylish fan. Her facial expression suggests that she has assumed the pose in response to a remark or perhaps a compliment made by someone who remains invisible.

According to Rafael Ocasio, mulata de rumbo was a colloquial phrase used to describe a “freed black woman whose financial circumstances had improved through sexual contact with wealthy white men.”[28] However, the term also denotes an implied relationship between these sexual liaisons and the mulata’s freedom of movement within Havana’s urban spaces. The word “rumbo” refers to a course, direction, or movement to a particular place. Therefore “mulata de rumbo” alludes to a dark-skinned woman who wanders the streets in full view, hoping to be solicited. Gelabert’s story “La mulata de rumbo” further discloses the defining characteristic of the costumbrista character.

The story centers on Leocadia, the mulata kept mistress of a well-to-do older gentleman named Gerardo Botero. Leocadia lives an easy life surrounded by luxury: “Believe me . . . [she tells her poor neighbor Juanita] I am fed up with all this gold and silk.” Yet, she yearns to attend the city’s African dances, at the time popular entertainment venues for white men soliciting mulatto women. Unable to subdue her angst, Leocadia plans an outing to one of the city’s parties in the extramural neighborhood of El Vedado with Floro, a mulatto friend, and Camilo Botero, coincidentally the nephew of Gerardo. Despite living under Gerardo’s tutelage, the young Camilo decides to pursue the love of the beautiful mulata. As the story progresses, Leocadia and Camilo become lovers without realizing they had been seen together by another of Leocadia’s admirers and acquaintance of Gerardo. Envious of Camilo’s success in winning the mulata’s affection, this individual, who is not given a name in the story, informs Gerardo of his nephew’s amorous entanglements with Leocadia.

Alerted to the illicit affair, Gerardo ends his financial support of Camilo and Leocadia. Now on their own, the young couple struggles to maintain their previous lifestyle. Leocadia is forced to pawn her jewelry in order to host her upcoming birthday party. Camilo offers to conduct the transaction. Upon exiting the pawnshop he is robbed at knifepoint and forced to surrender the money received for Leocadia’s jewelry. Not wanting to disappoint his lover, Camilo decides to forge his uncle’s signature in order to obtain the amount previously lost. The plan succeeds, and the money is spent on Leocadia’s party. The celebration ends on a sour note as the police arrive to arrest Camilo for the forgery. His incarceration is a devastating blow to Leocadia’s middle-class lifestyle, and she is forced to relocate with Juanita. As a result, Leocadia falls into a great sadness; however, her spirits lift eight days later with the arrival of a new well-to-do suitor who recovers her jewelry from the pawnshop. The story concludes with the return of Leocadia’s jewelry (a symbol of her middle-class status), which she proudly exhibits as she walks the streets of Havana with the “provocative facial expression” (semblante tan provocativo) found in Landaluze’s print.

Gelabert’s story reveals a more complex definition of the “mulata de rumbo.” More than a street walker, the text details the construction of the mulata “type” as a woman moving through the hands of various white men. Through this progression, she infringes on the stability of the middle-class kinship by seducing men of the same family and provoking the economic and social downfall of young Camilo. The cycle is set to repeat with the presence of the new lover. In addition, the story describes the mulata’s unwillingness to remain confined to the domestic realm as a defining attitude, thus highlighting the differences in social behavior between mulatas and criollo women.[29] Moreover, the urban environment is endangered by her return. Her sexuality poses new threats to young white men, such as Camilo, who attend the city’s dances and are blinded by desire.

The story also suggests that the mulata’s livelihood and display of wealth was completely dependent on her lovers. She, unlike Juanita who is forced to hustle (arrear) day after day to feed a household of seven, does not engage in any type of labor pursuits. Her ascension into the middle class would not have been possible through any means other than sexual exchanges with wealthy white man. Labor opportunities for free women of color in nineteenth-century Cuba were rather limited. Even the girls that were institutionalized from an early age in Casa de Beneficencia, an orphanage and house for the poor which educated and trained women in various trades, found themselves working as servants in wealthy households, mostly as seamstresses and ironers.[30] Costumbrista articles describe black women’s occupations as housekeepers, fruit sellers, babysitters, and wet nurses.[31] Leocadia however, does not appear to engage in any of these activities. Her profession consists of exploiting sexual exchanges with white men, who, as a result of the affairs, jeopardize their family relations or eventually fall into vice and thievery.

In short, the costumbrista discourse articulated by Landaluze and Gelabert defined the “mulata de rumbo” as a dark-skinned woman in motion, highly desired by white men, and ultimately a femme fatale figure. Working along these lines, the marquillas exploited the mulata’s dangerous sexuality as an advertising tool that activated male desire for the image. The prints often portrayed the body of the mulata as abundant and sexually available. The next section will examine how tobacco manufacturers employed the figure of the mulata to construct salacious jokes based on everyday life in Havana.

Reading Popular Humor

The marquillas’ representation of daily life relied on local systems of signification that combined costumbrista characters, proverbs, and colloquialisms with Havana’s city spaces. The use of popular proverbs, also common in Cuban literature, in combination with the local settings functioned as an authenticating mechanism that simultaneously lent the marquilla an air of present-day relevance.[32] One of the most complex examples in which these textual and visual signs come into play can be seen in a marquilla labeled No se tire que hay cloaca (Don’t jump in, there is a sewer; fig. 4). The print is organized along the lines of marquilla conventions, which included a central image called the escena; a top register containing the company name, exhibition medals, and other decorative elements that varied depending on the manufacturer; and the emblema or company trademark on the far right. The term escena (scene), borrowed from theater, describes a theatrical sequence, allowing the enclosed picture to function as a “freeze-frame” in a pictorial narrative.

Foregrounded in the escena, a young white man and a dark-skinned woman become the protagonists in an urban play. Sporting a fashionable burgundy suit, the man tightly grabs the woman’s dress with his right hand, while inserting his left hand in his pantaloons’ pocket. Meanwhile, the woman taps his shoulder as she leans in to whisper in his ear. The viewer soon discovers that the woman is not only darker-skinned but also older than the rosy-cheeked dandy. It is clear that he has ventured far from the “honorable” neighborhoods of the city into the extramural territories. The setting is carefully constructed to look like a street bordering the margins of Havana. A bodega and a tradesman (bodeguero) on one side typify urban life and economic exchange, while the vegetation in the background alludes to the city’s boundaries.

Observing the exchange, the bodeguero (right) and a criollo woman behind a barred window (left) flank the couple on either side. The bodeguero, whose hands are pressed against his cheeks, eyebrows raised and eyes widened, voices his concerns, No se tire que hay cloaca (Don’t jump in, there is a sewer). According to the Real Academia Española, in addition to sewer conduit, “cloaca” refers to a dirty, contaminated place, or the defecating orifice of certain animals and birds from which genital and intestinal fluids are discharged.[33] This word would have resonated with the contemporary viewer of the marquilla, since Havana's sewer system was commonly known as “las cloacas de La Habana.”[34] The comparison between the city’s sewers and the mulata’s body sets the premise for the joke. The mulata’s sexuality, coded as dirty and contaminated, poses an immediate threat to the young white man who naively pursues the affair.

On the left side of the marquilla, a criollo white woman observes the exchange taking place in front of the bodega; however, her figure is somewhat undefined and fades into the background in colorless form. The nineteenth-century viewer would have quickly identified the characters in the print. In 1859, the Directorio de artes, comercio, e industrias de La Habana recorded 786 bodegas operating in the capital city and its suburbs.[35] The figure of the bodeguero was not only ubiquitous in the city, but bodegas were a common iconographic trope in the representation of illicit sexual encounters between white men and mulatto women.

A related scenario unfolds in another marquilla captioned Escuela de primeras letras (Primary school; fig. 5). This time, a teenage mulata walks between two well-dressed young white men in front of an establishment named Bodega del Gabilan (Bodega of the Hawk). The men seem to be bidding for the girl’s companionship. The dandy wearing a fashionable burgundy jacket and matching red pants offers a golden coin, while his competitor on the left side raises the bid with a small pouch of coins. On the far left, a bodeguero observes the interchange; however, his figure is blurred and has not been treated with the same amount of detail. The inscription on the street window of the bodega closely ties the establishment to the three figures in the center. The contraction “del” in “Bodega del Gabilan” indicates the male gender of the hawk. The text references the two men in the center of the marquilla who are competing to pick up their “prey” from the streets of Havana. The joke lies in the questionable victimhood of the young mulata, for whom the front of the bodega is a “primary school” where she learns how to make financial decisions by extending her right hand to the man offering the highest bid.

There is also a similarity in the treatment of the background figures in this marquilla and in No se tire que hay cloaca. Similar to the bodeguero and the undefined African woman in the far background of Escuela de primeras letras, the criollo woman in No se tire que hay cloaca, appears blurred and decolorized. This white woman is also a common character of Para Usted’s marquillas. Seen in another print, captioned Naranja de china buena (The sweet tangerine; fig. 6), an elegantly dressed criollo woman stands behind a barred window, while a mulata holding an open door addresses a guajiro, a farmer who sells his produce in the city. The mulata has stepped outside the house, where she most likely works as a housekeeper, and extends her left hand to the guajiro offering her a fruit. The phrase sets up the joke by comparing the produce to the mulata’s body. She appears loosely dressed in comparison to the white woman. Her shoulders, arms, and upper chest are bare while a soft cloth delineates her large breasts whose “fruitful” shape humorously relates to the “sweet tangerine.” The white woman is made to observe the scene as she grips the iron bars. This gesture indicates her social status as a prudent woman and her inability to escape the domestic realm. The mulata on the other hand, is not bound by criollo gender codes and is free to step outside into public space.

The juxtaposition between the white woman (enclosed behind bars) and mulata (free to move within public spaces) is observed with clarity in No se tire que hay cloaca. While the mulata seduces the young white man on the street, the criollo woman remains a passive observer pushed into the background. Her representation behind the barred window is also part of the island’s national types as seen, for example, in El amante de ventana (The lover at the window; fig. 7), illustrated by Victor Patricio Landaluze in Los cubanos pintados por sí mismos (1852). El amante de ventana portrays a common courting practice in nineteenth century Cuba.[36] In the illustration, the window mediates the love affair of an unmarried white woman and her male suitor on the street. The bars function as a physical barrier preventing her from exiting her dwelling, thus protecting her chastity and honor. The marquillas narrate a very different story. The white men, who unlike their female counterparts have full access to public spaces, seem to be more interested in pursuing mulatas than love affairs mediated by a barred window.

The settings in these marquillas are closely related to the figures in the print and the activities they engage in. For example, the attire and dark complexion of the woman in No se tire que hay cloaca, correlates with the hybrid space, neither city nor country, in which she is represented. In the complicated categorization of race within these marquillas, her color and dress situates her in between an African woman and a mulata fina (a light- skinned middle-class mulata). Two other prints by Para Usted further illustrate the analog relationship between race, gender, and space. In one, an African woman appears barefooted while her loose blouse exposes her right breast (fig. 8). The woman extends her opened palm—holding a coin as if she has received payment from a young white soldier who is in the midst of tying his belt. The caption below voices the woman’s demand for payment: “DEPUÉ QUE COMITE LA PAPA SALÁ.” The bozal language expression becomes an immediate indicator of the woman’s race and social status.[37] The phrase, which in correct Spanish should read “DESPUÉS QUE TE COMISTES LA PAPA SALADA” (After you have eaten the salty potato) omits the pronoun “te,” the “s” from the words “despué(s)” and comi(s)te(s), and shortens salada to salá. The woman’s incorrect pronunciation exposes her African roots. Once more, the joke operates within the image and text relationship. The colloquialism of “eating the salty potato,” interchanges the body of the woman with the flavor of a produce. However, this darker woman dressed as a peasant is not “sweet” as is the one in figure 6, but rather “salty.” In this marquilla, skin color, speech pattern, attire, and behavior correspond to the primitive setting the woman is presented in. Her very dark complexion, nudity, badly spoken Spanish, and direct request for payment indicate that she is poor, uneducated, and perhaps a slave. In addition, the blatant reference to prostitution takes place outside a bohio, a hut typical of the Cuban countryside.

A very different encounter is reproduced in the other marquilla, Nuevo sistema de anuncios para buscar colocación (fig. 9). Here, a light-skinned mulata strolls through one of Havana’s alamedas, the city’s public walking spaces, most likely the Paseo de Isabel II, as hinted at by the city wall in the far background. In striking contrast to the peasant dress of the African woman standing outside a bohio, this lighter mulata sports a brightly colored dress over a crinoline, a pink and white shawl, an open fan, and an elegant hat. Now in a middle-class space of leisure, the mulata is cordially greeted by two gentlemen. Although her response is not made available to the viewer, the direction of her gaze acknowledges the men’s flirtatious remarks. In the lower foreground, her exposed right shoe provides an essential clue revealing the mulata’s intentions. The raised step uncovering the shoe and stocking can be seen in another of Landaluze’s prints, titled La fisiología del calzado (The physiology of footwear; fig. 10), in which the step is denominated as one that “produces street passions” (Los que producen pasiones en la calle). The marquilla’s caption reading NUEVO SISTEMA DE ANUNCIOS PARA BUSCAR COLOCACION (New advertising system for job searching) ties together the toe-tip step iconography with the mulata’s profession as a prostitute. The phrase “buscar colocación” functions as a double entendre. The most common connotation, “looking for a job,” suggests that the mulata strolls through the alameda in search for a job, or rather a client. On the other hand, the phrase could also mean “seeking placement.” This last interpretation relates to a common trope associated with the mulata de rumbo who perpetually seeks integration into criollo middle-class society by engaging in sexual liaisons with white men. The dubious provenance of her elegance and display of wealth signals to her previous success in such endeavors.

Both marquillas engage in the construction of race through skin color and attire, but also through location. The barefooted, African woman in figure 8 is pictured in a rural area where human presence is implied by bohios. Her language and attire match the peasant dwelling where she is represented. She wears simple peasant garments, and the exchange of sex for money is explicitly stated by her exposed breast, the presence of a coin in her opened palm, and her active demand for payment. The light-skinned mulata’s interaction with the two white males (fig. 9) is less obviously venereal, and her interpretation as a prostitute is largely dependent on the caption and the step exposing her right foot. Like the African woman, this mulata also belongs to the space she inhabits. Her whiter skin has allowed her to enter the alamedas and to wear the latest European fashions. The colors of her flowered dress match those of the gardens she parades through, allowing her to blend in and become one more flower of the promenade.

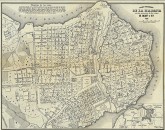

Halfway between city and countryside, continental African and light-skinned mulata, the woman in No se tire que hay cloaca, likewise belongs to the extramural street on the outskirts of Havana in which she is presented. To envision mid-nineteenth century Havana, one must consider the great spatial divide between the old city isolated by a wall some 33-feet high (intramuros), and the “New Havana” of the extramural outskirts (See map in fig. 11). Throughout the early nineteenth century, the city’s economic hub and elite families resided in the vicinity of the port inside the walled easternmost section of the city, while the extramuros, where the dark-skinned mulata is situated, was an area of emerging urbanization largely inhabited by working-class Spaniards, mulattos, and freed slaves. However, following extramural developments, notably marked by the construction of Villanueva Rail Station, a grand theater, and the renovation and paving of extramural promenades (1834–38), the New Havana became a site of interest for wealthy criollo residents and tobacco manufacturers aiming to expand their working facilities beyond the wall.[38] Particularly under Miguel Tacón’s administration (1834–38), the once-marginalized territories became contested spaces from which local authorities and businessmen tried to ban undesirable sectors of the urban population.[39]

The portrayal of a dark-skinned mulata and a young dandy engaging in improper behavior while in public in No se tire que hay cloaca, highlights the local government’s inability to reform the extramural territories. Nevertheless, the print is set to intervene in the indecent engagement by ridiculing the white youth. While two of the previous marquillas, illustrated in figures 6 and 8, associate the women’s body with flavor—either “sweet” or “salty,” this one suggests a sense of smell, and it is not a pleasant one. To his detriment, the youth is unaware that he is about to “jump onto” the filthy body of a dark-skinned street prostitute. The woman’s profession as a sex worker is symbolized by her exposed feet; the right foot assuming the subtle toe-tip iconography of Landaluze’s “fisiología del calzado.” Once more, the visual clue implies that the mulata is offering a service that “produces street passion,” and the dandy whose hands are divided between the mulata’s dress and his pocket, is paying for it.

The Butt of a Joke

The marquillas’ ability to widely disseminate humoristic narratives centered on the localized interactions of popular types made it possible for tobacco manufacturers to establish a series of dialogs with their local audience. The conversation was mediated by a type of Cuban satire, which some scholars have termed choteo.[40] The word “choteo” derives from the verb chotear, which the Real Academia Española defines as: “To joke, or have fun at the expense of someone else.”[41] Choteo can happen anywhere, at any time. It permeates every stratum of Cuban society, and anyone acting improperly according to his class, race, gender, age, or position in life is susceptible to ridicule. In the context of the marquillas, Fraunhar adds that choteo “customarily takes as its target opportunism and naiveté.”[42]

If we analyze the marquillas under the lens of choteo, a new reality comes to life. In No se tire que hay cloaca, the correlation between “cloaca” as sewer conduit, and the mulata’s vagina, alludes to an unpleasant surprise for the mulata’s soon-to-be client. The dandy’s inability to foresee the immediate dangers associated with the dark-skinned woman makes him the perfect target for choteo. His desire for the mulata has caused him to act outside the manners of bourgeoisie society where he belongs—implied by his nicely matched burgundy suit, lined vest, bowtie, and hat—leading to his indecent entanglement with a street prostitute in broad daylight. As a result of his misconduct, which, according to the caption, will cause his eventual fall into the “sewer,” the dandy is subject to ridicule and subsequently becomes the butt of the joke.

Noting the young man’s naiveté, the bodeguero on the right seems increasingly alarmed by the course of events. The caption voices a warning call: NO SE TIRE QUE HAY CLOACA. More than sewer conduits, the cloacas were sources of infestation, where waste water and accumulated trash gave life to deadly epidemics.[43] The juxtaposition of cloaca with mulata creates a disturbing parallel between human waste and the body of the woman—a parallel that was closely associated with modern urban reform and public health in the capital city.

In 1833, Havana fell victim to an outbreak of cholera, which resulted in approximately 8,300 deaths by the end of the following year.[44] The spread of the disease was seen, in part, as a result of water pollution caused by a quasi-medieval system of waste disposal. The absence of a sewer system led citizens to empty their waste into the streets, whence it was then carried by floods and tropical storms into the city’s port and drinking water deposits.[45] The imminent threat of widespread contagion allowed colonial officials to politicize disease control as a state of emergency in order to implement hygienic codes and fund urban renovation projects.[46] In the aftermath of the epidemic, Governor Miguel Tacón (1775–1855) embarked on Havana’s first major urban renewal, with mass street-paving projects, including the alamedas previously mentioned; the construction of the city’s first sewers, a grand theater, and a prison; and the enforcement of public health measures such as the mandatory construction of residential drains, trash collection, and biweekly street sweeping.[47] The discourse of modern salubrity aimed to clean up the streets not only from human waste, but also from criminals, beggars, and anyone threatening the social order. The newly constructed prison facility with a capacity for 2,000 inmates was quickly put into use by Tacón’s iron-fist police force, who began cracking down on thieves, assassins, illegal gambling houses, and even idleness.[48]

Propagating public health reform and civil order were of particular interest to tobacco manufacturers who employed large segments of Havana’s urban population. In 1862, the colonial census reported 149,060 individuals living within the city’s jurisdiction (a 78% increase since 1817), and approximately 200,000 with the addition of adjacent municipal territories.[49] The drastic population increase was directly fueled by the 516 cigar factories and 38 cigarette manufacturers operating in Havana and its extramural territories in 1861. In 1862, these businesses employed 17,428 workers whose income sustained approximately 47,600 individuals amounting to nearly one third of the city’s population.[50]

Cigarette manufacturers actively participated in the city’s modernization efforts by advocating personal hygiene using their most powerful tool: the marquillas. By the early 1860s, preoccupation with cleanliness became visible in the prints of La Honradez. In a comedic episode titled Un paseo por la alameda (A leisurely walk through the alameda; fig. 12), Havana’s iconic fountain statue, La India has stepped down from her pedestal in order to clean up and get ready for Columbus’s visit. The monument of La India was erected by Cuban criollo oligarch Conde de Villanueva (1782–1853), together with Havana’s first rail station in 1837.[51] The statue, which celebrated the arrival of modern urban reforms and the renovation of Paseo de Isabel II (fig. 13), appears in the marquilla washing herself using the water of the fountain she sits on. The gesture suggests that Havana was a dirty city, one in need of cleaning. On a second marquilla (fig. 14), depicting Columbus’s arrival, La India exclaims in Castilian vernacular: “Ya estoy limpia y arreglada; y vosotros ¿cuándo os lavaréis? (“I am clean and dressed up; and you? When will you wash yourselves?”). In this public service announcement, La India speaks on behalf of the tobacco manufacturer and asks the general public to clean themselves.

Unfortunately for La India, the alameda she adorned was also a preferred site for mulatas looking to advertise their services to middle- and upper-class white men, as shown in Nuevo sistema de anuncios (fig. 9). In the marquilla, the mulata’s seductive stroll taints the renovated public avenues with lust and indecency. Her public presence subverts the discourse of modern reforms by coding Havana’s urban environment as one infused with illicit sexuality. In the context of nineteenth-century Havana, this type of public self-advertising was closely associated with female delinquency. Prostitutes were loosely defined as “public women” (mujeres públicas), a term that did not describe sex workers exclusively, but a wide category of street women also including alcoholics, vagrants, and immigrants.[52]

The marquillas’ portrayal of mulata prostitutes seeking clientele in Havana’s public spaces reflected a preoccupation with the spread of sex work in the capital city. Such anxieties were shared by Dr. Benjamin de Céspedes, public health worker, and author of La prostitución en la ciudad de La Habana (1888), who expressed his concerns regarding the activities of public women of color in Havana: “Abandoned between concubinage and prostitution, and without anyone to attend to their betterment, [women of color] propagate debauchery (desenfreno) and Africanism in public customs, like a terrible moral epidemic.”[53] Céspedes’s poignant connection between prostitution, African female bodies, and the circulation of disease, further highlights how the white middle and upper classes viewed the mulata’s sexuality as source of both moral and physical contagion.

For Céspedes, prostitution was not a public health issue affecting just a segment of the population, but an epidemic that spread throughout the city invading every corner and neighborhood. During the middle of the nineteenth century, Havana’s economic prosperity attracted large numbers of European immigrants, former slaves, and prostitutes.[54] This last group capitalized on the gender disequilibrium caused by the predominantly white male immigration. In 1861, historian Jacobo de la Pezuela y Lobo reported 91,625 white men and 46,820 white women living in the city.[55] Sixty eight percent of white men were between the ages of sixteen and forty, and 71.5 percent over the age of thirteen were listed as single.[56] On the other hand, the gender distribution of the city’s free black population (including mulattoes) was rather different. The same year, Pezuela reported 15,326 black men to 20,058 black women.[57] It is no surprise that the marquillas’ representation of daily life in Havana depicted young white men pursuing mulatas and vice-versa.

The inevitable consequences of the city’s gender disequilibrium seem to have been keenly experienced by tobacco manufacturers, whose neighborhoods (both inside and outside the wall) were invaded by prostitutes looking to take advantage of the increasing demand for sex work.[58] Throughout the middle and late nineteenth century, Havana’s bourgeoisie vigorously protested the presence of “public women” in their neighborhoods. Such was the case with intramuros business owner Doña Isabel Bistori who, on October 12, 1863, filed a police complaint denouncing the immoral conduct of several prostitutes residing and working near her high-end dress shop on 60 Compostela Street. Bistori lamented the unavoidable sight of the women, claiming that in addition to “offending the decorum and decency of the neighborhood,” these women negatively affected her clientele of “proper ladies” who “wished to avoid both their own and their daughter’s exposure to improper language and sight of women engaged in dishonorable behaviors.”[59] Despite the affirmative action taken by local police, who evicted the women in question, Bistori’s dilemma was far from resolved. Commenting on the dispute, Police Chief Cazariego wrote: “Experience has demonstrated that as soon as we respond to one local resident’s complaint and order prostitutes in question to move . . . others quickly arrive to take their place.”[60] By the 1860s, public officials such as Cazariego considered the relocation and control of prostitutes a futile task, since women facing eviction and the subsequent loss of property often sublet their residences to colleagues who continued to practice their trade.[61]

Prostitution was illegal in Cuba until 1853, when Havana’s Police commissioner Antonio de la Encina acknowledged the ineffectiveness of prohibition and suggested that a tolerance zone was the only logical solution to the ongoing problem. Under the new tolerance policy, prostitutes were to relocate to La Punta, the easternmost section of the extramuros territories. However, many of these women continued to practice their trade in the central areas of the city, since relocating to La Punta meant the loss of wealthy clientele and exposure to the high traffic of Havana’s commercial districts.[62] The owner and managing staff of Para Usted, whose headquarters were located at Oficios 23, on a street in the immediate vicinity of Havana’s port—a common area for prostitutes seeking clientele from incoming ships—most likely witnessed the impact of prostitution at first hand. The marquillas reflected the tobacco manufacturer’s anxieties over the spread of sex work, and the high visibility of its practice in the capital city. In the prints, sex-for-money exchanges take place everywhere from the countryside to the city’s promenades. These women not only disregard authority, but also corrupt it. Such can be observed in Depué que comite la papa salá (fig. 8), in which a white man in uniform carrying a baton represents a Havana police officer who has abandoned his post in the city and ventured into the countryside in search of illicit sex. Once more, the man’s actions have led him to become a victim of choteo. His misconduct as a public official indulging in sex for money with a black woman negates the very idea of law and order that his uniform symbolizes. In this scenario, the marquilla uses choteo to mock the officer’s improper behavior, which has caused him to lose control over the subject he is supposed to police.

Depué que comite la papa salá also commented on the local government’s failure to effectively regulate prostitution in Havana. Prior to leaving office in 1867, Police Chief Cazariego stated: “I am aware of the laxity with which officers approach their duty with regard to government orders, especially those pertaining to public women.”[63] Cazariego’s successor, Don Raul Rivero, acknowledged the problem by adding: “I have come to understand that local officers sometimes give their explicit consent to these infractions,” a practice he aimed to “correct with a firm hand.”[64] The marquilla’s exposure of the police officer’s sexual exchanges with a black woman for hire speaks to Para Usted’s interest in contemporary debates regarding civil order in the capital city.

The marquillas’ visualization of interracial sex-for-money exchanges also brings to the fore the ways in which women of color resisted or entered into conflict with the colonial order. Their liaisons with white men were problematic on multiple levels. First, interracial sex disregarded Spanish obsession with limpieza de sangre or purity of blood.[65] Second, these unions were seen as detrimental to the stability of institutionalized slavery, which was not abolished in Cuba until 1886.[66] Already in 1852, one public official expressed his mistrust of the racial mix caused by the civil unions between white men and women of color: “In the present circumstances it would be doubly damaging to open the hand and grant these [marriage] licenses, for the truly dangerous class or at least that which must be watched over this island, is that of the mulattos, whether free or slaves.”[67] These tensions were aggravated by the start of the United States’ civil war, which raised new anxieties regarding racial mixing and the possibility of a slave revolt on the island. Prior to 1864, licenses for interracial marriages were rarely denied.[68] However, following the defeat of the Confederacy, the Spanish colonial government assumed a new attitude toward racial mixing. From 1864 until the mid-seventies, not a single such marriage license was granted.[69] The marquillas speak to the threat posed by the mulata: the byproduct and catalyst of racial mixing. They portray the mulata’s sensuality as unhygienic, morally degrading, and dangerously capable of disturbing the civil order. Her uncontrollable presence, as both the quintessential figure of prostitution and an active carrier of contagion, endangered Havana’s urban environment, and thus the young white men who dwell in it.

The marquillas also participated in the construction of race by juxtaposing the mulatas with ideal representations of European female beauty. For example, in No se tire que hay cloaca, the mulata’s dark-skinned body is coded as salacious by comparison to the white maiden in the company’s trademark. Placed within a bucolic landscape, the white maiden wears a similar crinoline; however, her shoulders and upper arms are covered. In addition to skin colors, racial difference is highlighted by the activities these women engage in. The rosy-cheeked white woman is surprised by the viewer in the midst of collecting flowers, an activity which underlined European ideals of chastity and female beauty.[70] The mulata, on the other hand, appears as a seductress of innocent youths. In addition, the slight changes in the hair color of the trademark figure further indicate the tobacco manufacturer’s obvious intent to create a clear racial distinction between the trademark figure and the mulata in the escena. In marquillas portraying darker-skinned women, such as No se tire que hay cloaca and Depué que comite la papa salá, the maiden in the trademark appears as brunette; however, in prints representing mulatas finas, such as Nuevo sistema de anuncios (fig. 9), the maiden’s hair is blond, rather than brunette.

It is important to note that the opposition between mulata and the immaculate white figure in the company’s trademark illuminates a set of moral frontiers. The maiden picking flowers, which serves as the company’s official image, represents an ideal of white purity, free of moral and racial contamination. The marquillas’ composition in itself reflects a preoccupation with establishing the differences between a respectable criollo woman and the mulata streetwalker. The various mulatas are positioned side by side with the stock figure of the white maiden. In addition to setting opposite boundaries of dirty versus clean, pure versus impure, the women are contrasted by the different spaces they inhabit and the framing devices that separate them. As if contagion existed within the marquillas themselves, the white maiden is encapsulated, or shall we say quarantined, within three frames: the oval portrait frame, the rococo cartouche, and the enclosing rectangle sectioning off the emblema. Similar to the criollo woman in the background of No se tire que hay cloaca, the maiden is secluded and safe from any unwanted contact with the mulata. This separation implies that the mulata’s public presence not only afflicted white men, but also criollo women who witnessed the world through colonial-barred windows.

Within the various initiatives taken by tobacco manufacturers to reform civic life in Havana, the education and correction of women was of primary concern. On May 8, 1864, El Diario de la Marina reported with great enthusiasm the opening of a new “asylum-workshop” named “Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes,” for training women in the art of rolling cigarettes. Sponsored by Cárlos Beauguillot, director of La Honradez cigarette factory, the workshop housed fifty women and their children, who previously resided in Casa de Beneficencia. The all-female factory was in a repurposed former hospital, San Leopoldo, “where currently pernicious illnesses such as moral discouragement and physical inertia are cured,” expressed female correspondent Felicia.[71] Beauguillot’s efforts to employ the women housed in Casa de Beneficencia were seconded by another cigarette manufacturer, Francisco Javier Balmaseda, who, on November 10, 1865, secured the institution’s approval to open a cigarette workshop inside its facility. This second shop was to supply raw materials to twenty five women employees, and pay them according to their daily cigarette production.[72] In addition to employing the women in Casa de Beneficencia, cigarette firms such as La Honradez also printed material for the early education of working class girls in Havana. In April of 1866, Luis Susini, owner of La Honradez, announced that his state-of-the-art print shop would begin supplying free printed material to local schools for poor girls (colegio de niñas pobres), “La Caridad” and “El Corazon de María.”[73]

Tobacco manufacturers’ support of women’s public education reflected an interest in controlling the social roles of women and, most importantly, providing them with opportunities to earn a decent living once outside the Casa de Beneficencia. Becoming skilled laborers of Havana’s largest industry would diminish the probability that they would turn into public women. With this in mind, one must reconsider the depictions of mulatas in the marquillas. The prints allude to the damaging impact of public women in civic life. They expose the mulata’s public presence as an ongoing threat to social order. In a city where unmarried young white men greatly outnumbered their female counterparts, the mulata was seen as both a coveted commodity and a hazardous body. Through the satirical mechanism of choteo, the marquillas not only condemned the young white men’s unruly desire for the mulata, but also warned them against the implicit dangers associated with her body.

Conclusion

The reading of the marquillas offered in this article unveils the ways racialized humor activated a set of sensorial experiences associated with the sexual consumption of the mulata’s body. Ranging from sweet, to salty, to foul, the bodies represented were simultaneously coded as both desirable and contagious. These experiences were mediated by the marquillas, which were to be touched, smelled (as cigarettes packs usually are), and closely inspected. The intimate manipulation of the prints allowed the smoker to fetishize the mulata through the miniature image, and in turn develop a desire for the marquilla itself. However, the sensory experience of physically interacting with the mulata becomes one of contamination, as the body of the dark-skinned woman is compared to the city’s cloacas.

As a form of subliminal advertising, the marquillas were successful in translating the mulata’s body into an image to be consumed. As a social warning, they regarded the mulata’s public presence as a city-wide epidemic affecting the future of young white men, and thus, that of the colonial patriarchal power structure. The jokes articulated in the prints sought to entertain the smoker through the use of local settings and popular culture. Simultaneously, these humoristic narratives were charged with moral allegories that aimed to educate young white men in times of urban expansion and nascent cosmopolitanism. The marquillas’ capacity to circulate in the smoker’s daily life allowed them to reach where the colonial order could not: they infiltrated micro-interactions and mediated exchanges between bodies, while their narratives outlined moral and spatial boundaries in a city where modernity correlated with instability. Thus, by propagating the mulata’s sexuality as a morally corrupting, physically contagious malady moving throughout Havana’s urban environment, and ridiculing white male desire for women of color, the marquillas reinforced and disseminated the state’s rhetoric condemning interracial sex as detrimental to the civil order and social hygiene of the Cuban capital.

A previous version of this article was presented at the Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art’s Twelfth Annual Graduate Student Symposium, at which I received most valued feedback from participants and audience members alike. In addition, I wish to express my gratitude to Beatriz Balanta, Francisco Morán, Lisa Pon, and Petra ten-Doesschate Chu for their insightful and constructive criticism. Erin Piñon and Rheagan E. Martin also revised earlier versions of the text. I would also like to thank Adrianna Stephenson for helping me prepare the images for publication, and Robert Alvin Adler for his patience and editorial assistance.

All translations by the author, unless otherwise indicated.

[1] Benjamin de Céspedes, La prostitución en la ciudad de La Habana (Havana: Establecimiento Tipográfico O'Reilly, 1888), 171, GoogleBooks, accessed March 20, 2015, https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=IQQYAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&pg=GBS.PR3.

[2] It is unclear when color-illustrated marquillas were first used to package cigarettes in Cuba. According to Zoila Lapique, prior to the 1860s, lithographic shops in the island operated manual presses and printed in one color; however, after 1861, the brothers José and Luis Susini, owners of La Honradez cigarette factory, began importing new printing technologies (chromolithography), which they used to package their cigarette production. Zoila Lapique Becali, La memoria en las piedras (Havana: Ediciones Boloña, 2002), 209. In his annotated bibliography of published Cuban works related to Don Quijote, surgeon and librarian Manuel Perez Beato notes 1861 as the probable date for six marquillas by La Honradez: “Don Quijote ante su Dulcinea,” “Cosas de antaño,” “Don Quijote,” “Manteo de Sancho,” “El molino de viento,” “El bálsamo de Fierabrás.” Cuba y America 19, no. 17 (July 23, 1905): 318, GoogleBooks, accessed September 15, 2015, https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=IvUsAAAAYAAJ.

[3] The word “costumbrista” derives from Costumbrismo, a popular trend in nineteenth-century literary and visual arts of Spain, France, and Latin America. Costumbrista artists and writers aimed to capture local customs, interactions, and costumes of everyday people. See Mey-Yen Moriuchi, “From ‘Les types populaires’ to ‘Los tipos populares’: Nineteenth-Century Mexican Costumbrismo,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013), accessed August 17, 2015, http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring13/moriuchi-nineteenth-century-mexican-costumbrismo.

[4] In this article I use “women of color” to refer to women of African descent, including mulatas.

[5] Alison Fraunhar, “Marquillas Cigarreras Cubanas: Nation and Desire in the Nineteenth Century,” Hispanic Research Journal 9, no. 5 (2008): 458.

[6] Ibid., 477.

[7] Madeline Cámara Betancourt, “Between Myth and Stereotype: The Image of the Mulatta in the Nineteenth Century, a Truncated Symbol of Nationality,” in Cuba, the Elusive Nation, ed. Damian J. Fernandez and Madeline Cámara Betancourt (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000), 100.

[8] Vera M Kutzinski, Sugar's Secrets: Race and the Erotics of Cuban Nationalism (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1993), 7.

[9] The marquillas discussed in this article were all produced or commissioned by cigarette manufacturers operating in Havana. According to Hippolyte Piron, who visited Cuba’s major urban centers in the early 1870s, cigarettes were only manufactured in the capital. Hyppolyte Piron, L’ile de Cuba: Santiago, Puerto-Principe, Matanzas et La Havane (Paris: E. Plon et cie, 1876), 290, Archive.org, accessed September 15, 2015, https://archive.org/details/lledecubasantia00pirogoog.

[10] The individually printed marquillas are shown in figs. 4, 6, 8, and the two in the series “Historia Mulata” are shown in figs. 5, 9.

[11] Antonio de Gordo y Acosta, El tabaco en Cuba: Apuntes para su historia (Havana: La Propaganda Literaria, 1897), 42; and Third Biennial Directory of the Tobacco Trade of the United States, Canada, and Cuba (New York: The Tobacco Leaf Publishing Company, 1877), 655. A copy is in the New York Public Library.

[12] Most of the scholarship on the marquillas is based on the prints published by Antonio Núñez Jiménez in Marquillas cigarreras cubanas. Jiménez’s publication surveyed the largest marquilla collection known: three Albums de cromos housed in La Biblioteca Nacional José Martí, which according to the author contained 3,932 exemplars from multiple manufacturers. Antonio Núñez Jiménez, Marquillas cigarreras cubanas (Madrid: Tabapress S.A., 1989), 35. Since the albums are currently missing from the Biblioteca Nacional, Jiménez’s publication remains the primary source for the material. Out of the 244 marquillas reproduced by Jiménez, fifty-one bore Para Usted’s logo. A few dozen marquillas survive today in Album de Marcas de M.R., housed in the Universidad de San Gerónimo, Havana. In this second collection, one can find sixteen of Para Usted’s prints. The Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, has digitized five albums containing 253 marquillas which can be seen here, each accessed August 24, 2015: Marquillas cigarreras cubanas: J. Esclapet (30 prints), http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000163867; Marquillas cigarreras cubanas: Fábrica Para Usted (183 prints), http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000014890; Marquillas cigarreras cubanas (11 prints), http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000163865; and Marquillas cigarreras cubanas: La Dignidad (20 prints), http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000163866; and Album Cecilia G. de la Rigada 1874 (12 prints), http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000063819&page=1.

[13] Samuel Hazard, Cuba with Pen and Pencil (Hartford, CT: The Hartford Publishing Company, 1871), 146.

[14] See excerpt taken from the New York Herald in Luis Susini é Hijo, Real Fábrica La Honradez, 2nd ed. (Havana: La Real Fábrica La Honradez, 1865), 23–24, GoogleBooks, accessed June 23, 2015, https://books.google.com/books?vid=HARVARD:32044088988332&printsec=titlepage#v=onepage&q&f=false. This publication compiled guests’ opinions and newspaper articles that described the factory’s highly technological operations and the philanthropic spirit of its owners. Also see Hazard’s account of his visit to La Honradez in Hazard, Cuba with Pen and Pencil, 146–52.

[15] The factory’s daily production and number of employees can be found in Luis Susini é Hijo, Real Fábrica La Honradez, 45.

[16] Hazard, Cuba with Pen and Pencil, 149.

[17] According to the account of Alejandro Tapia y Rivera, La Honradez packaged cigarettes in two types of paper packages. The “common” packs (monochrome) held twenty-four units, while the papers printed in color, which he referred to as “luxury packs,” held twenty-five cigarettes. Luis Susini é Hijo, Real Fábrica La Honradez, 49.

[18] Havana’s cigarettes were also exported to Europe, Latin America, and the United States. According to Jose Rivero Muñiz, Cuban cigarette manufacturers exported a total of 8,855,551 packets in 1859. José Rivero Muñiz, El tabaco y su historia en Cuba (Havana: Instituto de Historia, Academia de Ciencias de la República de Cuba, 1965), 2:281.

[19] Hazard’s reference to the “opera house” most likely referred to the grand Teatro Tacón, located in the immediate outskirts of Havana’s wall. Hazard, Cuba with Pen and Pencil, 145.

[20] According to Narciso Menocal, during the 1850s cigarette smoking was “growing popular and becoming widespread among men and women” in Cuba. Narciso Menocal, Cuban Cigar Labels: The Tobacco Industry in Cuba and Florida: Its Golden Age in Lithography and Architecture (Coral Gables: Cuban National Heritage, 1995), 5.

[21] Luis Susini é Hijo, Real Fábrica La Honradez, 49.

[22] The “barrel pack” in La cajetilla bocoy is referenced by Alison Frauhnar and Agnes Lugo-Ortiz as an illustration of a functioning marquilla. Fraunhar suggests that the marquillas acted as a “wrapped bundle,” while Lugo-Ortiz simply adds that the print “provides an image of how such lithographed papers were used at the time.” Frauhnar, “Marquillas Cigarreras Cubanas,” 461–62; and Agnes Lugo-Ortiz, “Material Culture, Slavery, and Governability in Colonial Cuba: The Humorous Lessons of the Cigarette Marquillas,” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies: Travesia 21, no. 1 (2012): 64–65.

[23] Hazard, Cuba with Pen and Pencil, 155.

[24] Although the artists behind marquillas remain unknown, records indicate that Havana’s costumbrista artists often collaborated with cigarette manufacturers. Most notably, costumbrista painter and lithographer, Victor Patricio Landaluze, responsible for illustrating both Los cubanos pintados por si mismos (1852) and Tipos y costumbres de la Isla de Cuba (1881), collaborated with Juan Martínez Villergas, owner of the cigarette factory La Charanga de Villergas, in the design of the company’s marquillas. The same firm produced a series of fifteen prints entitled “Vida y muerte de la mulata” [Life and death of the mulata], which narrates the rise and fall of the mulata from conception to her ultimate demise. For further information regarding Landaluze’s collaborations with Villergas, see Adelaida de Juan, Pintura y grabados coloniales de cubanos (Havana: Edit. Pueblo y Educación, 1974), 12–13.

[25] Rafael Ocasio, Afro-Cuban Costumbrismo from Plantations to the Slums (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2012), 94–95.

[26] Costumbrista albums were collections of short stories and illustrations that detailed the types and customs of a country or region. The texts were known for using colloquialisms or speech patterns of the characters they described. Similarly, the illustrations portrayed “faithful” depictions of each type by concentrating on the costume or activity that distinguished each costumbrista character. The first published costumbrista album was Victor Patricio Landaluze and D. Jose Robles, Los cubanos pintados por sí mismos (Havana: Imprenta y Papeleria de Barcina, 1852), GoogleBooks, accessed August 17, 2015, https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=woQCAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover.

[27] Miguel de Villa, ed., Tipos y costumbres de la Isla de Cuba, intr. Antonio Bachiller y Morales, illust. D. Victor Patricio de Landaluze (Havana: Miguel de Villa, 1881), Archive.org, accessed August 17, 2015, https://archive.org/details/tiposycostumbres00bach.

[28] Ocasio, Afro-Cuban Costumbrismo, 103.

[29] The word criollo (noun) describes an individual of European parents that is born and raised in colonized territories of Hispanoamerica. In addition, criollo also functions as an adjective used to describe things or persons that are unique to the territory such as “criollo society” as opposed to Spanish society. In nineteenth–century Cuba, social codes of honor reproached criollo women who ventured out on the streets without a chaperon.

[30] Sarah L. Franklin, Women and Slavery in Nineteenth-Century Colonial Cuba (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2012), 108.

[31] See Francisco de Paula Gelabert, “Un puesto de frutas,” and “La partera ó La comadre” in de Villa, Tipos y costumbres de la Isla de Cuba, 117–21, 245–53.

[32] Kutzinski, Sugar’s Secrets, 71.

[33] Real Academia Española, Diccionario de la lengua Española, 22nd ed., s.v. “Cloaca,” accessed August 19, 2015, http://lema.rae.es/drae/?val=cloaca.

[34] Nineteenth-century authors frequently referred to Havana’s sewers as “cloacas.” For example, when analyzing the city’s use of water from the polluted Zanja Real (Havana’s oldest aquaduct), Dr. Marcial Dupierris commented that the Arsenal (Havana’s shipyard) utilized the water only to run its mills. He later added that “we would have observed with much pleasure, that this water would have been equally applied to clean the city’s cloacas (aseo de las cloacas de la ciudad).” Marcial Dupierris, Memorias sobre la topografía médica de La Habana y sus alrededores (Havana: Imprenta la Habanera, 1857), 28, GoogleBooks, accessed August 24, 2015, https://books.google.com/books/reader?id=eLIqINnGZ80C&printsec=frontcover.

[35] Directorio de artes, comercio, e industrias de La Habana (Havana: Librería de A. Graupera, 1859), 19–26.

[36] The representation of lovers courting through a barred window is a common trope in Cuba’s nineteenth-century visual culture. The inclusion of El amante de ventana as a “type” in Los cubanos pintados por sí mismos (1852) speaks to the popularity of the practice in mid-nineteenth century Cuba.

[37] The term bozal described slaves born in Africa. In addition, the word was often used to refer to an Afro-Cuban speech pattern characterized by its inaccuracy and the speaker’s inability to correctly pronounce the Spanish language.

[38] For information regarding urban development under General Tacón’s administration, see Joseph L. Scarpaci, Roberto Segre, and Mario Coyula, Havana: Two Faces of the Antillean Metropolis (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 32–37.

[39] For a detailed discussion of Havana’s extramuros’ demographics, criminality, and state policing activities, see Yolanda Díaz Martínez, Visión de la otra Habana: Vigilancia, delito y control social en los inicios del siglo XIX (Santiago de Cuba: Editorial Oriente, 2011), 25–41.

[40] Alison Fraunhar, Diana Aramburu, and Narciso Menocal have previously discussed the humor on the marquillas as choteo. Fraunar and Aramburu built upon Jorge Mañach y Robato’s definition of the term choteo, which he articulated in a 1928 lecture series published as Jorge Mañach y Robato, La crisis de la alta cultura en Cuba: Indagación del choteo (Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1991), and in e-book form as Jorge Mañach y Robato, Indagación del choteo (Red Ediciones S.L., 2011), accessed August 17, 2015, http://www.digitaliapublishing.com/a/14991/indagaci-n-del-choteo. [Purchase required.] In the lecture, Mañach considers choteo as detrimental to “high culture” in Cuba because it denies importance to that which should be taken seriously. In other words, the mockery mechanism behind choteo dismisses the gravity of a situation or issue. Agnes Lugo-Ortiz suggests Mañach’s discussion on choteo reflected “his own anxieties about the social and cultural dynamics of early Republican Cuba and not necessarily an analytical category to project retrospectively (and with the risk of ahistoricity) into the dynamics of the nineteenth century,” and, thus, she concludes that the humor on the marquillas should not be discussed in terms of choteo. While I do not find Mañach’s definition of choteo suitable for discussing the marquillas, I believe the term as used by Menocal, and as I define it in the text, accurately describes the type of satire that unfolds on the marquillas. See Lugo-Ortiz, “Material Culture, Slavery, and Governability,” 83; Menocal, Cuban Cigar Labels, 11–12; Fraunhar, “Marquillas Cigarreras Cubanas,” 465; and Diana Aramburu, “Las fiestas afrocubanas en las marquillas cigarreras del siglo XIX: El ‘Almanaque profético para el año 1866,’” Afro-Hispanic Review 29, no. 1 (Spring 2010), 18–19.

[41] Real Academia Española, Diccionario de la lengua Española, 22nd ed., s.v. “Chotear,” accessed August 20, 2015, http://lema.rae.es/drae/?val=chotear.

[42] Fraunhar, “Marquillas Cigarreras Cubanas,” 465.

[43] Pedro M. Pruna, La real academia de ciencias de la habana 1861–1898 (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2004), 337.

[44] Enrique Beldarraín Chaple and Luz María Espinosa Cortés, “El Cólera en la Habana en 1833: Su impacto demográfico,” Revista Electrónica de Historia 15 no. 1 (February-August, 2014): 164, doi:10.15517/dre.v15i1.8372.

[45] Dupierris, Memorias sobre la topografía, 28.

[46] Adrián López Denis, “Higiene pública contra higiene privada: Cólera, limpieza y poder en La Habana colonial,” Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe 14, no. 1 (2003): 11–33.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Scarpaci, Segre, and Coyula, Havana: Two Faces, 33. Also see Díaz Martínez, Visión de la otra Habana, 62–63.

[49] José A. Piqueras Arenas, La Habana colonial: (Visiones y mediciones, 1800–1877) (Santa Cruz de Tenerife: Idea, 2006), 16–17.

[50] Muñiz, El tabaco y su historia, 2:288–89.

[51] Eduardo Torres-Cuevas and Oscar Loyola Vega, Historia de Cuba: 1492–1898: Formación y liberación de la nación (Havana: Editorial Pueblo y Educación, 2002), 150.

[52] Nineteenth-century texts often associate prostitution with public indecency. In La prostitución en la ciudad de La Habana, Dr. Benjamin de Céspedes opens his discussion by quoting the Roman jurist Ulpian, who defined prostitution as “comercio público” (public commerce). Céspedes, La prostitución, 2. Also see Tiffany A. Sippial’s discussion of “public women” in Tiffany A. Sippial, Prostitution, Modernity, and the Making of the Cuban Republic, 1840–1920 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 26–27.

[53] “Abandonada entre dos soledades: el concubinato y la prostitución, y sin que nadie atienda á su mejoramiento, vá propagando como terrible epidemia moral, el desenfreno y el africanismo en las costumbres públicas.” Céspedes, La prostitución, 171.

[54] Sippial, Prostitution, Modernity, 18–33.

[55] Population statistics provided by Jacobo de la Pezuela y Lobo, Diccionario geográfico, estadístico, histórico de la Isla de Cuba (Madrid: Imprenta del Establecimiento Mellado, 1863), 3:6–8, Hathitrust.org, accessed August 31, 2015, http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.32106019739058;view=1up;seq=15. An analysis of Havana’s mid-nineteenth century demographics using Pezuela’s figures can be found in Pilar Pérez-Fuentes and Lola Valverde, “La población de La Habana a mediados del siglo xix: Relaciones sexuales y matrimonio,” Historia Contemporánea, no. 19 (1999): 155–79.

[56] Pérez-Fuentes and Valverde, “La población de La Habana,” 157.

[57] Pérez-Fuentes and Valverde cited Pezuela’s gender breakdown of Havana’s black population as the following: 31,434 black men to 35,344 black women, out of which 15,326 men and 20,058 women were free. Ibid.

[58] According Céspedes, by the 1880s every neighborhood in Havana was rife with mulata prostitutes. See Céspedes, La prostitución, 176. Although one might question the accuracy of Céspedes’s statement, by 1888 five city jurisdictions had been denominated as zones of tolerance due to the overwhelming numbers of prostitutes living and working in Havana. Juan Andreo García and Alberto José Gullón Abao, “‘Vida y muerte de la Mulata’: Crónica ilustrada de la prostitución en la Cuba del XIX,” Anuario de Estudios Americanos 54, no. 1 (1997): 138, doi:10.3989/aeamer.1997.v54.i1.402. García and Gullón Abao also add that already in 1873 Old Havana (intramural city) was in its entirety “a grand center of prostitution.” Ibid., 139.

[59] Police complaint quoted and translated from the Archivo Nacional de Cuba, Govierno Superior Civil, legajo 1038, no. 36073 (queja 1863), in Sippial, Prostitution, Modernity, 41–42.

[60] Sippial, Prostitution, Modernity, 41–42.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid., 33–34.

[63] “Police document, Prefectura Principal de Policía (Havana)” March 1, 1867, Miscellaneous Manuscript Collection, Yale University, as cited and translated by Sippial, ibid., 45–46.

[64] “Police documents, Prefectura Principal de Policía,” August 20, 1867 and October 2, 1867, Miscellaneous Manuscript Collection, Yale University, as cited and translated by Sippial, ibid., 46.

[65] Verena Martinez-Alier, Marriage, Class and Colour in Nineteenth-Century Cuba: A Study of Racial Attitudes and Sexual Values in a Slave Society (New York and London: Cambridge University Press, 1974), 15–19.

[66] Martinez-Alier, Marriage, Class and Colour, 32–33.

[67] Govierno Superior Civil, legajo 1148, no. 43925, Archivo Nacional de Cuba, Havana, quoted and translated by Martinez-Alier, ibid., 32.

[68] Ibid., 31.

[69] Ibid., 32.

[70] The maiden in the garden is a popular iconographic motif in European painting. Representations of aristocratic women holding flowers in gardens can be found in Franz Xavier Winterhalter, The Empress Eugenie Surrounded by her Ladies in Waiting (1855), a work which celebrated aristocratic ideals of female beauty and virtue.

[71] An excerpt from Felicia’s article initially published in El Diario de la Marina on May 8, 1864, can be found in Luis Susini é Hijo, Real Fábrica La Honradez, 33.

[72] Excerpt from El Siglo, November 10, 1865, reproduced ibid., 41–42.

[73] Luis Susini é Hijo, Real Fábrica La Honradez, 117–118.