The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

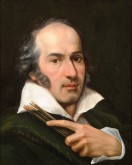

A Self-Portrait by Francesco Mezzara (1774–1845), the Italian Painter Who Changed New York State Constitutional Law with a Pair of Ass’s Ears

Introduction

Two years ago, I visited a private collection in Belgium to look at a painting said to be by Anthony van Dyck. The painting was not worth the visit, but my curiosity was piqued by another piece in the collection, a self-portrait by the looks of it, painted by an unidentified artist (fig. 1). Because it was covered with layers of dark varnish, I suggested to the owner that he have it cleaned. Unexpectedly, the restorer uncovered the full signature of the artist, “Francesco Mezzara,” as well as a date, 1806.

As I began to research the painting, it seemed at first impossible to retrace Mezzara. It was not until I checked—by a lucky coincidence—a database on the history of law that I came across his name. Further research revealed not only that his self-portrait is the only known painting by the artist to have been preserved, but that Mezzara was instrumental in changing New York state constitutional law.

The Portrait

In his self-portrait (oil on canvas, 47.1 x 38.7 cm; fig. 1), Mezzara presents himself to the viewer with a self-assured demeanor. His eyes meet the viewer’s gaze, and with the index finger of his right hand he points to a lengthy inscription on his lapel. In the same hand, he holds seven thin brushes, their hairs dipped in different color paints.

The artist seems to be past the age of youth. His hairline is receding and his temples and sideburns are graying. He is dressed in a moss-green coat over a white shirt. The shirt’s wide raised collar and open cuffs reflect the fashions of the early nineteenth century. The artist painted his portrait several years before he married in Paris shortly before 1813.[1] Because there is no evidence about the exact date when Mezzara moved to France, it remains unclear whether he received his training in Italy or France. But the style of the self-portrait suggests that Mezzara was familiar with late eighteenth-century neo-classical portraits, notably by Pompei Batoni (1708–87) and followers such as Gaspare Landi (1756–1830).[2] This suggests that he may have studied in Rome with an unidentified artist.

Who was Francesco Mezzara?

A few salient facts about the painter Francesco Mezzara are provided by the inscription on the lapel of the artist’s coat: “Francesco Figlio di Gioseppe e di Angiola Romano se fece TA 1806” (fig. 2).[3] The inscription informs us that Francesco Mezzara came from Rome and that his parents were Gioseppe and Angiola Mezzara.[4] Little is known about his parents, his youth in Rome, or his artistic training. All we know is that at some point he moved to France,[5] where he is known to have married shortly before 1813. The Parisian register of births, marriages, and deaths indicates that “Thomas- François-Gaspard Mezzara, peintre d'histoire” married Marie-Angélique Foulon (Paris, 1793−Paris, 1868).[6] According to her death certificate, she was, like her husband, an artiste peintre.[7] In 1813 the couple lived at 16 rue d’Enfer in Paris. As far as can be ascertained, the painter first traveled to New York in February 1817.[8] It appears that he stayed in the city for less than a year, which was long enough, however, for him to get into legal trouble, resulting in a trial (more about which below). In 1818, a year after the trial, the Mezzaras were registered as living in Paris again, this time at 89 rue de Charonne.[9] But some time in 1819, they seem to have once again traveled to New York, where the couple’s first son, Joseph-Ernest-Amédée Mezzara was born on March 2, 1820 (d. Paris, 1901).[10] Shortly before 1825, the young family returned to France, where the next two children were born. Pierre-Alexandre-Louis Mezzara saw the light in Evreux on December 9, 1825 (d. Paris, January 30, 1883)[11] and his sister, Marie-Adèle Angiola Mezzara, named after her paternal grandmother, was born in Paris on August 1, 1828.[12] It is possible that a second daughter, Clémentine, was born to the couple some time later. We have no biographical information about her, but in 1847, one Clémentine Mezzara was living at 11 Quai Napoléon, the same address where Francesco Mezzara and his wife are known to have lived between 1837 and 1848.[13] The prestigious address suggests that by then the family was prosperous, though the source of their prosperity is not exactly known.[14]

We do know that Madame Mezzara continued to work as an artist even after her children were born. Living in Evreux in 1825, for example, she produced two portrait drawings of prominent local residents,[15] and she regularly exhibited her portraits at the Salon.[16] But what about Mezzara himself? What works of art did he produce? It is curious that, with the exception of the self-portrait, we cannot attribute a single work of art to him. In the 1820s, he evidently taught Italian in New York,[17] while trying at the same time to exhibit his works of art. In 1823, a certain “M. Mezzara” exhibited a portrait at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.[18] But despite this and perhaps other exhibits, Mezzara did not succeed in establishing a reputation in the US, which may explain why he returned to France shortly afterwards. There is only one clue regarding a change of course in Mezzara's professional activities. The archives of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris contain two letters written by Mezzara. The first is an introductory letter addressed to “Monsieur Quatremère de Quincy, Secrétaire Perpetuel de L'Académie des beaux arts.” This was undoubtedly the art theorist and historiographer Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy (1755−1849), who acted as “permanent secretary” to the Parisian Academy in the period 1816−1839. Mezzara’s second letter, with the salutation, “Messieurs,” was addressed to the members of the Academy. The letters are undated, but it can be inferred from the context that they were written in 1828.[19] What were they about? François Mezzara (he used the French spelling of his first name, here) wished to draw the Academy members’ attention to a marble relief “originating from Rome,” which had been made some thirty years earlier by the British neoclassical sculptor John Deare (1759 − 1798) (fig. 3). He was asking the Academy’s members to supply an “approval” for the relief, which he was considering selling in the capacity of an art dealer. We do not know whether Mezzara received the approval or if he sold the relief, which today is at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. But it seems likely that Mezzara, later in life, operated as an art dealer of antiquities and, perhaps, contemporary art as well. The Academy’s records refer to him as an archéologue,[20] which suggests that he may have excavated or bought antiquities in Italy and sold them in the international market.

Mezzara died in Paris on February 3, 1845.[21] After his death, his wife remained active as a painter, exhibiting at the Salon until 1849.[22] Both their sons became artists. Joseph Mezzara became a student of the neoclassicist painter Jean-Pierre Granger (1779−1840), the sculptor David d'Angers (1788−1856), and the painter Ary Scheffer (1795−1858), all important artists of the Romantic School.[23] Between 1852 and 1875 he submitted works of art—mainly marble portrait busts of prominent contemporary figures—to the Paris salon.[24] Pierre, also known as Pietro, achieved international success as a sculptor, most notably in the United States.[25]

The Mezzara Trial

Francesco Mezzara is remembered not primarily as an artist or as an art dealer, but for his role in a precedent-setting legal case, which led to a change in New York State constitutional law.

On August 4, 1817, in New York City Hall, Mezzara was convicted of “criminal libel.”[26] Mayor Jacob Radcliff (1764–1842) presided over the trial, which issued from a conflict between a prominent lawyer and the artist, who had arrived in New York six months earlier. The lawyer, Aaron H. Palmer (1792–1863), was described as “a counsellor and attorney at law in this city, and a master in chancery and public notary.”[27] He accused the portrait painter Francesco Mezzara of bringing him “into public hatred, ridicule and contempt,” claiming that Mezzara “falsely and maliciously did make, utter and publish a certain picture, portrait or resemblance of the said Aaron H. Palmer with the ears of an Ass.”[28] It took the jury all night to arrive at their verdict against Mezzara, who was sentenced to pay a $100 fine.

The New-York City-Hall Recorder for August 1817 published a record of the entire proceedings, down to the smallest detail.[29] Ever since then, “Mezzara's Case” has been regarded as one of the cases ushering in a new stage in New York State constitutional law in which the definition of libel was not restricted to written statements. Forms of “symbolic expression,” such as paintings and caricatures, could also transgress the bounds of acceptability and constitute criminal acts.[30] While the case has attracted the scrutiny of legal historians on multiple occasions, it seems clear that the conviction brought an end to Francesco Mezzara’s career and hence to his role in art history. An attorney with an interest in the history of the New York constitution has recently claimed that “the main protagonists at the trial—Mezzara and Palmer—seem to have left no recognizable traces behind.”[31] But the self-portrait of Mezzara and a portrait of Aaron Palmer, painted two years after the trial by the leading New York portrait painter, John Wesley Jarvis (1780; fig. 4)[32] bely that statement.

Aaron H. Palmer met Francesco Mezzara at a dinner party thrown by “Baron Quenette” or Nicolas-Marie Quinette, baron de Rochemont (Paris, 1762-Brussels, 1821), a French politician and aristocrat, at his home in New York. Mezzara was introduced to Palmer as “a man of genius and an eminent connoisseur in the fine arts.”[33] At that time, the “artist from Rome”[34] had only been in the city for six months. During the dinner, Mezzara proposed to paint Palmer’s portrait “and was very solicitous that he should sit for that purpose; saying that there was a very striking peculiarity in the forehead, and that Palmer’s head was perfect for a head study—expressing it in French as “une tête d'étude.”[35] Palmer must have felt flattered by this remark, and under some pressure from Mezzara, he accepted the artist’s proposal. When he saw the portrait in an unfinished state, Palmer did not express any dissatisfaction.[36] Yet when Mezzara brought the completed, framed painting to the Academy of Arts, where Palmer and some of his friends had an opportunity to inspect it, the attorney was apparently less satisfied with his portrait; he “considered it as unworthy of an artist of eminence; and his friends pronounced it to be a caricature.” His friends’ opinion seems to have played a decisive role. In a subsequent encounter with the painter on Broadway, Palmer told Mezzara that he was “much displeased and disappointed,” but, being a man of his word, he would not hesitate to pay the painter. He “offered and tendered him the full charge for the painting, which was $65.”[37]

Palmer honored his agreement with Mezzara but nevertheless profoundly insulted the painter by telling him to keep the portrait. Mezzara asked Palmer to put this in writing, and he did so without delay.[38] The artist, “considering his professional skill decried,” accused Palmer of wounding his feelings and “self-love” and refused to accept the money offered. Later that day, after the first heat of rage had cooled, Mezzara changed his mind and sent a young man named Thomas Blanchet to collect the money from Palmer. But now the attorney refused to pay for the portrait, because he had offered to do so earlier and the painter had declined. Mezzara, unwilling to accept this outcome, brought a legal action against his sitter. This suit was unsuccessful and Mezzara was ordered to pay $24 in court fees.[39] But their conflict did not end there. On the evening of the verdict, Mezzara ran into the attorney again on Broadway. Palmer was with two friends at the time, Barent Gardenier (1776–1822), a lawyer and US Congressman of Dutch origin, and Isaac M. Ely, Esq.[40] In response to Mezzara’s belligerent behavior, Palmer informed the painter that he owed him nothing, since he had initially made such a generous offer. Nevertheless, the painter managed to persuade the three friends to come to his studio, where he kept Palmer’s portrait. A discussion ensued about the resemblance (or lack thereof) between the model and his portrait, “wherein he [Mezzara] was very abusive, (finding that those gentlemen did not concur with him in opinion respecting the likeness).” As the men were about to leave the room, Mezzara picked up a piece of chalk and drew “Ass’s ears” on the head in the picture, threatening to add them in oil paint and then exhibit the painting on Broadway.[41] Barent Gardenier’s later testimony corroborated Palmer’s account of the incident. Gardenier confirmed that the three men had visited Mezzara’s room in Reed Street, “where he exhibited to them the picture for their opinion or approbation.” He also attested that “the language of the defendant [Mezzara] towards Mr. Palmer was intemperate.” He described Mezzara’s threat regarding the donkey’s ears and added that the artist had evidently made this threat “with a design of wounding Palmer’s feelings.” The report continues: “Palmer however kept his temper, and seemed to smile, but the witness [Gardenier] thinks it gave him pain.”[42] No doubt Palmer had already decided that their dispute would not end there.

He called on the services of a well-known painter of the day, the aforementioned John Wesley Jarvis. At Palmer’s request, Jarvis confirmed “that he is a portrait painter by profession; that he had seen the picture said to be the likeness of Mr. Palmer, before it was disfigured, in Mezzara’s room; that it was an imperfect likeness, and rather a botch than the performance of an accomplished artist.”[43] Palmer had probably chosen this expert witness very carefully. In the early 19th century Jarvis shared with Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828) the distinction of being “New York's leading portraitist” and had “received the plum commission to paint six large portraits of the heroes of the war of 1812” for the City Hall.[44] His authority as a portrait painter was incontestable.[45] Jarvis’s testimony at the trial probably wounded Francesco Mezzara more deeply than Palmer’s lack of appreciation.

When the deputy sheriff, Jonathan L. Brewster, visited the painter in July 1817 to collect the $24 in court fees,[46] Mezzara claimed that “he had no other property to satisfy the execution except the picture . . . which the witness [the deputy sheriff] recognized as the likeness of Mr. Palmer.”[47] The only possible course of action was to sell the painting. The Frenchman John Cheneau, a friend of Mezzara’s, acted as guarantor for the delivery of the picture on the day of the sale, which was set for July 30, 1817. When Brewster arrived to pick up the portrait that day, “on calling for the picture, [he] found it disfigured by the appendage of Ass’s ears to the head.”[48] According to the later testimony of the Frenchwoman Maria Brunet, Francesco Mezzara had previously asked the sheriff “if he could be injured by reason of the transformation above mentioned, and the sheriff answered in the negative.”[49] The sale of the painting attracted unusually great interest, and by that time Palmer had caught wind of what had happened to the portrait. He instructed the deputy sheriff to arrange for up to $30 to be bid so that the painting could be destroyed; a clerk in the auction house placed the bid.[50] But Palmer had miscalculated. A friend of Mezzara’s bid $40 and acquired the painting. Mezzara immediately paid his outstanding debt of $24 to the sheriff and believed the matter closed.[51]

But Palmer, ever the attorney, would not let it rest, and brought a lawsuit against Mezzara. This fascinating and highly significant case involved arguments explicating the difference between the laughable and the ridiculous.[52] The opening section of the report on this trial in the New-York City-Hall Recorder refers to the Elements of Criticism (1762) by Henry Home, Lord Kaimes (1696–1782), “a judge in the Supreme Courts of Scotland” and a pillar of the Scottish Enlightenment. Home’s proposed distinction between a laughable and a ridiculous object forms the central theme of the arguments that follow: “And he further observes, that an object that is neither risible nor improper lies not open, in any quarter, to an attack from ridicule; that an irregular use made of a talent for wit and ridicule, cannot long impose on mankind: it cannot stand the test of correct and delicate taste; and truth will at last prevail even with the vulgar (1 El. Crit. P. 306).”[53] Although the court acknowledged that “there are some laughable incidents peculiar to this case,” it denied “that ridicule is attributable to the conduct of Mr. Palmer.” Mezzara was charged not only with having added the donkey’s ears to Palmer’s portrait and then offering the painting for sale, but also with asking the auctioneer to exhibit it “in a more conspicuous place, that it might be inspected by the people.” Moreover, he had placed an advertisement in a New York newspaper, the Republican Chronicle, to announce the sale:

Curious Sheriff's Sale. We have been requested to mention, that there will be sold, this forenoon, at public vendue, at No. 133 Water-street, a PICTURE intended for the likeness of a gentleman in this city, who ordered it painted. But as the gentleman disclaimed it, it remained the property of the painter . . . who is an eminent artist from Rome [and] has decorated it with a pair of long ears, such as usually worn by a certain stupid animal. The goods can be inspected previous to the sale.[54]

In short, the painter had done everything in his power to bring the dispute to public attention and to pique the curiosity of the people of New York. The advertisement was written by Samuel Woodworth (1784−1842),[55] an American author, poet and literary journalist, who may have felt sympathy for Mezzara’s foolhardy attempt to obtain justice.

The case for the prosecution was made by two attorneys, a Mr. Wilkins and William M. Price:[56]

1. Although the portrait was not a perfect likeness of Aaron Palmer, “it so far resembled him that all his acquaintance knew that he was the person whom the picture designed to represent. The appendage which was superadded, was manifestly added to hold him up to public ridicule.”

2. The testimony by Gardenier, corroborated by Ely, showed that the painter intended to take revenge on Mr. Palmer by adding donkey’s ears to the picture, initially in chalk and later in oil paint.[57]

3. At the sale, he had the painting placed where it would be the center of attention, and the advertisement drew even more people than would otherwise have attended. Even after the auction, once Mezzara had regained possession of the picture, he would not stop showing it to as many people as possible: “He exhibited the picture in a triumphant manner in the streets.” Wilkins spoke of “the atrocity of such conduct” and “emphatically enquired, Where is this conduct to stop? What is to deter the defendant [Mezzara] from exhibiting this picture in our streets, again and again, but the wholesome restraint of a verdict?” Wilkins went on to warn the jury that if they found Mezzara guilty, the same fate might await them: “He will draw your pictures with his Ass's ears.”[58]

4. When Palmer relinquished his rights to the portrait to Mezzara, this did not imply that the painter was permitted to perform unlawful acts with it. Furthermore the painter drew the ears of an ass to the picture in chalk and used “intemperate language to Palmer.” The prosecution interpreted this as “a circumstance, manifesting the mischievous intention of the defendant.”[59]

J. C. P. Sampson was the painter’s primary defense attorney, and the report tells us that he brought “much energy and humor” to this role. His defense was based on four contentions:

1. “That this was either a likeness of Mr. Palmer, or it was not a likeness. If a likeness, it was his duty to have paid the painter; if not, the appendage of Ass's ears, on a picture not a likeness, was not a libel on him more than on any other individual.”

2. Mezzara was not guilty of “a publication of the picture.” The sheriff, acting as the agent of A. Palmer, should not have taken the portrait to the auction room on the day of sale, because the agreement pertained to a different portrait: namely, a portrait without donkey’s ears.

3. Palmer had claimed that the portrait was not his likeness and had given the painter the right to do whatever he pleased with it.

4. The painter had invested a great deal of time and money in painting the portrait and therefore had the right, as soon as it became his property, to seek the best possible price for it. If he wanted to transform the painting in question into a picture of King Midas—“he actually intended to metamorphose the picture into a representation of Midas; and was not actuated by any malicious or mischievous intention towards Mr. Palmer”[60]—then he had every right to do so. The defense added that even if Mezzara had harbored malicious intentions, it was important to recall that he was a foreigner, “unacquainted with the severity of our laws on the subject of libel.”[61]

In his jury instructions, the mayor offered the following conclusion: although “the libel, charged in the indictment, was in nature private, and, therefore, not important in a public point of view, yet the case, by reason of its peculiar nature, required their serious attention. Any publication, picture, or sign, made with a mischievous or malicious design, which holds up any person to public contempt or ridicule, is denominated a libel” [author’s italics]. In recapitulating the various arguments made, the mayor instructed the jury to consider that the final portrait was not the portrait that Palmer could reasonably have expected. He was unconvinced by the claim that the painter had wanted to transform the portrait into a scene of the mythical King Midas.[62] The jury took a long time to reach its verdict. It began deliberating at 11 p.m. and returned a verdict against the defendant the next day at 9 a.m.: “To see a pair of Ass's ears attached to the picture of any individual, however respectable, however worthy and venerable, he may be for learning or piety, it must be confessed, is a laughable object. But unless such individual has been guilty of some gross folly or impropriety, this appendage, attached to his representation, is incompatible with our ideas of moral fitness; the libel does not apply to the character of the man; and though we may laugh, we cannot ridicule.”[63]

Mezzara was ordered to pay a fine of $100.[64] Since he was not a wealthy man, and a “stranger” to boot, he did not receive any “more rigorous punishment.”[65]

Since Mezzara’s conviction was based upon the court having equated “symbolic expression” with “verbal expression,” the trial of 1817 acquired great historical importance.[66] In his quest for the historical roots of the view, which is still not always accepted to this day, that “symbolic expression . . . is basically functionally identical to expression through words and should thus be treated the same,”[67] Eugene Volokh cites the report in the 1817 New-York City-Hall Recorder. He writes: “The report of Mezzara's Case (1817), apparently the earliest American case involving symbolic libel there—a painting of the plaintiff with donkey's ears—likewise indicates that free speech and press principles were seen as applying to such symbolic expression.”[68] He ends by noting that the person who had reported on Mezzara’s trial in 1817 “saw nothing odd in treating a painting as protected by free speech and press principles, just as the court saw nothing odd in treating a painting as punishable under libel law principles.”[69] In Mezzara’s, case symbolic expression effectively had been equated with verbal expression. Accepting the equation, it became necessary, moreover, to prove or to deny that the painter’s “expression” was justifiable and inspired by good motives, as would have been the case if the painter would have expressed himself by using words.[70]

The verdict was clear. The motives of the painter Mezzara had not been honorable. By adding the “donkey’s ears”—an act of “symbolic expression”—he was attempting to take his revenge on his unenthusiastic client, the attorney Aaron H. Palmer. The person who reported on the trial likewise observed, with some sympathy, “if he published and exhibited the picture with good motives and for justifiable ends . . . would he not be justifiable under our statute?”[71]

Mezzara’s Gesture in Historical Perspective

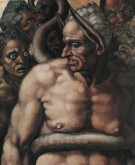

The well-documented story of the portrait painter Francesco Mezzara is interesting not only from a legal but also from a cultural-historical vantage point. History teaches us that situations of this kind were not uncommon, although few reached the courts.[72] As a Roman, Mezzara was undoubtedly familiar with the way in which Michelangelo had taken his revenge on the papal master of ceremonies Biagio da Cesena for venturing to criticize the numerous nudes in his fresco of the Last Judgment. The artist depicted his castigator in hell as King Midas and gave him a pair of gigantic donkey’s ears (fig. 5).

We may be sure that Mezzara had visited the Sistine Chapel, and he may have read about the event in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives.[73] We find similar comical tales of “mutilated” portraits in the writings of authors such as Karel van Mander (1604) and Cornelis de Bie (1661). Van Mander gives a spirited account of the way the sixteenth-century painter from Mechlin, Jacques de Poindre (or De Punder) (Mechelen, 1527−Denmark, after 1570) took his revenge on an obstreperous client. De Poindre had been asked to make a portrait of a British captain named Pieter Andries. The artist did not have an easy character, being what the author describes as a “great troublemaker” (een groot brageerder). Jacques de Poindre painted his portrait, but the man was unhappy with it, and left the painting with the artist without paying for it. The portraitist took his revenge by painting prison bars in front of the man’s face, using watercolors. His actions produced rapid results: the captain came and questioned De Poindre’s gesture. De Poindre calmly responded that his visitor would remain “imprisoned” until he had paid for the portrait. The captain immediately handed over the money, and was eager to see the bars disappear. De Poindre took a sponge and wiped them away. That was the end of the matter. The painter had received his payment and the captain decided to keep the portrait after all.[74]

The tale told by the notary Cornelis de Bie, from Lier, is even more similar to the Mezzara case. The story concerns the painter Gillis Mostaert (Hulst, 1528−Antwerp, 1598), who excelled both in depicting “curious models” and in secular and religious history paintings. De Bie tells about “a curious trick” Mostaert played on a nobleman whom he had depicted so skillfully and convincingly that the only thing lacking in the portrait was life and speech. But the nobleman was “stung by self-importance, and maintained that the portrait was not a good likeness, that it was too brown.” He threatened to withhold payment unless Mostaert improved it. But Mostaert felt the client’s response as an insult to his professional pride. He promised to improve the portrait, and then, without touching the face, “gave him a jolly fool’s cap using watercolors.” Having done so, he deliberately publicized the portrait, “standing it outside his door every day.” And since the nobleman was well known in the city, “all passers-by were astonished to see such a respectable man wearing a fool’s cap.” Tongues started wagging, and the nobleman soon heard of the matter. Irate, he set off to the painter’s house, where he saw “his own likeness in the character of a fool.” He flew into such a rage that he would have murdered the painter on the spot, had he been at home. He then summoned Gillis Mostaert, who came straight away, “undismayed and with a perfectly serene expression,” to ask him what he wanted. When the man asked him “why he had made such a mockery of him, and furthermore made an exhibition of him in the street outside his house,” Mostaert replied that he was astonished to find “that [his client] recognized himself as soon as he was wearing a fool’s cap, having failed to do so when he had been painted as a wise man.” De Bie added, by way of a moralizing conclusion, that one does not acquire self-knowledge until one has been exposed to “the mockery of all the world.”[75] The sixteenth-century captain and the nobleman were both taught chastening lessons by their portraitists, who reversed the customary relationship between patrons and painters by holding their clients up to public ridicule.

When Francesco Mezzara took up a piece of chalk and added donkey’s ears to the painted portrait of Aaron H. Palmer, he was acting in a way that was not unprecedented. But he was ill-prepared for the reaction that his impulsive gesture would generate in New York. Due to the charges that were brought against him, his chances of becoming the portrait painter of New York’s high society were destroyed.

Katlijne Van der Stighelen

katlijne.vanderstighelen[at]kuleuven.be

Acknowledgments: I am grateful to Jan de Meere for numerous inspiring discussions. I should also like to thank Bert Demarsin for his interest and his critical comments on the article. The article is translated from the Dutch by Beverley Jackson. My thanks to Robert Alvin Adler for his meticulous editing.

This article is dedicated to my (lawyer) son Govert Coppens.

[1] See the French genealogy site run by Jacques Lemarois, The Lemarois Site, s.v. “Marotte du Coudray,” accessed January 22, 2014, www.lemarois.com/jlm/data/n17leleu.html, hereafter “Marotte du Coudray.”

[2] Pompeo Battoni’s self-portrait is in the Uffizi in Florence. See Caterina Caneva, Il Corridoio Vasariano agli Uffizi (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2002), no. 39; Landi’s portrait is in the Galleria Borghese. See Paolo Moreno and Chiara Stefani, The Borghese Gallery (Milan: Touring Editore, 2000), 14, 353.

[3] The meaning of “TA” in the inscription is unclear.

[4] There is no reliable evidence of the date of his birth. He seems to be about forty years old in the self-portrait, which would indicate a year of birth ca. 1765.

[5] The Dictionnaire des artistes de langue française en Amérique du Nord: Peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs, graveurs, photographes et orfèvres (Quebec: Les Presses de l’Université de Laval), 1990), 565−566, gives the dates inaccurately: “Francis Mezzara, père de Joseph Mezzara . . . artiste, étranger, qui était aux États-Unis de 1811 à 1824.”

[6] “Marotte du Coudray.” Marie-Angélique Foulon was the daughter of Nicolas Foulon and Madeleine Marotte du Coudray. On occasion of his marriage, Mezzara was described as “peintre d’histoire.”

[7] “Décès,” 9e arr., September 1, 1868, V4E 1051, Archives Départementales, Archives de Paris: “Foulon, V[euv]e Mezzara.” “Acte de décès: Marie Angélique FOULON, artiste peintre, âgée de soixante-quinze ans, née à Paris, décédée ce matin, à quatre heures trois quarts en son domicile, Rue Blanche, n°. 101, veuve de François Gaspard MEZZARA.” The death was reported by “M. Joseph Ernest Mezzara, sculpteur, âgé de quarante-huit ans, dem[euran]t à Paris, Rue d'Alambert [d’Alembert], n°. 16, fils de la défunte.”

[8] This date is derived from the report of trial in which it is stated that he came to the States six months before August 1817. He did not speak English, and during the trial there was no reference to earlier stays. Daniel Rogers, The New York-City-Hall Recorder for the Year 1817 Containing Reports of the Most Interesting Trials and Decisions Which Have Arisen in The Various Courts of Judicature, for the Trial of Jury Causes, in the Hall, During That Year, Particularly in the Court of Sessions, with Notes and Remarks, Critical and Explanatory 2, no. 8 (New York, 1817), 115. This volume, whose pages 113–18 are the principal source for the trial, will hereafter be referred to as NYC-HR.

[9] See “Marotte du Coudray.”

[10] E. W. C. Six, Museum Ary Scheffer. Catalogus van kunstwerken en andere voorwerpen, 2nd ed. (Dordrecht: Dordrechts Museum, 1934), 88.

[11] “Naissances,” December 10, 1825, Archives départementales de l'Eure, Evreux: Mezzara (Pierre, Alexandre, Louis), registered as the son of “Thomas, François, Gaspard Mezzara, peintre d’histoire, demeurant en cette ville, Boulevard Chambeaudoin” and “Angélique Marie Foulon, son épouse.”

[12] “Naissances,” August 1, 1828, V3E/ 1612, Archives départementales, Archives de Paris. The date of her death is unknown.

[13] Salon de 1847. Explication des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, architecture, gravure et lithographie des artistes vivants exposés au Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées (Paris, 1847), nos. 1890–91. First, a reference is made to “Mezzara (Mme Angélique), 11, Quai Napoléon, Portrait de Mme la Comtesse de Salvandy, pastel” and second a watercolor by “Clémentine Mezzara, 11, Quai Napoléon, Etude de Camélia, aquarelle” is mentioned. Mother and daughter, living at the same address were exhibiting on occasion of the same Salon.

[14] In 1847, shortly after the death of F. Mezzara, his widow moved to Rue Blanche, Cité Gaillard, no. 5. See P. Sanchez, Les Catalogues des Salons, V. 1846–1850 (Dijon: L’Echelle de Jacob, 2001), 144. The same address is listed in the notice of her death in 1868. “Décès,” 9e arr., September 1, 1868, VE4 1051, Archives Départementales, Archives de Paris.

[15] See Ville de Louviers, Musée: Peinture, sculpture, dessin, gravure, architecture, etc.; Catalogue Publié sous les Auspices de l’Administration Municipale (Louviers: n.p., 1888), 20: “Mezzara (Mme Angélique), no. 153. Portrait de Louis-Jacques-Amédée-Hector Ancel. Dessin fait en 1825; no. 154. Portrait de Noël-Louis Ancel. Date du dessin: 1825.”

[16] Between 1827 and 1849 her drawings, pastels and paintings were exhibited in Paris. See: “Database of Salon Artists,” University of Exeter, Arts and Humanities Research Council, s.v. “Mezzara (Madame Angélique),” accessed August 3, 2014, http://humanities-research.exeter.ac.uk/salonartists/public/work/index/order/livret_cat/direction/ASC/page/3?order=livret_cat&direction=ASC&.

[17] Howard R. Marraro, “Pioneer Italian Teachers of Italian in the United States,” Modern Language Journal, 28 (1944): 581–82.

[18] Giovanni Ermenegildo Schiavo, Four Centuries of Italian-American History (New York, Vigo Press), 1957, 228; and Anna Wells Rutledge, The Annual Exhibition Record of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1807-1870, ed. Peter Hastings Falk (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1955), 141.

[19] Béatrice Bouvier and François Fossier, Procès Verbaux de l'Académie des Beaux arts de Paris, vol. 4, 1826–1829 (Paris, École des Chartes, 2006), 33. This source refers only to the existence of the letters, without saying anything about their content. I am extremely grateful to Mireille Lamarque and Mireille Pastoureau of the Bibliothèque de l'Institut de France for making copies of these letters available to me.

[20] It is quite possible that Francesco Mezzara was also the author of a collection of lithographs depicting ruins. The edition is known as the Tower of the Giants in the Isle of Gozo near Malta. A review of this publication appeared in The Athenaeum and Literary Chronicle, July 1, 1829, 400: “The author is a M. Mezzara, a painter, and his work consists of eleven plates, from drawings on stone, after his own designs, and contains an account of what is called the discovery of the ruins of that ancient temple. This same giant's tower is conjectured by M. Mezzara, who examined it in 1827, to have been built before the deluge. Of the eleven plates, the first is a view of Gozzo from Malta; the next nine following are general and particular views of the temple in question, and the 11th represents what is called the Grotto of Calypso.” The reviewer sneers at Mezzara’s claim to have discovered these ruins himself: “But for claiming to Mr. Mezzari [sic] the merit of discovering them in 1827, there is no pretence whatever. They have been long well known also to the residents at Malta. . . . We believe it to be true, indeed, that they have never been published in such detail as they are now given in the work of Mezzara, which, if accurate, must be highly interesting.” It unfortunately proved impossible to find any of the prints from this ensemble. The reviewer noted that “Mr. Mezzara” was “very familiar with the region” and was “interested in archeology.” As Francesco Mezzara was born in Rome, not too far from Malta, was described as “archéologue” by the members of the Parisian Academy, and dealt in antiquities, there is a good chance that he may be the “Mr. Mezzara” who created the lithographs. Moreover, in the early 19th century, no other artist with the name of “Mezzara” is known. His claim to have “discovered” the ruins may be another indication of his ambitions and temperament.

[21] “Décès,” February 3, 1845, V3E/D 1056, Archives départementales, Archives de Paris.

[22] “Database of Salon Artists,” s.v. “Mezzara (Madame Angélique); and Émile Bellier de la Chavignerie and Louis Auvray, Dictionnaire général des artistes de l'école française depuis l'origine des arts du dessin jusqu'à nos jours: Architectes, peintres, sculpteurs, graveurs et lithographes (Paris: Renouard, 1885), 2:84, s.v. “Mezzara, Angélique.”

[23] Leo Ewals, Ary Scheffer, 1795–1858: Gevierd Romanticus, exh. cat., Dordrechts Museum, Dordrecht (Zwolle: Waanders, 1995), 12, 19–21, 57. It is asserted there that Scheffer and Joseph Mezzara first met in or around 1840. For the complex nexus of artistic relationships among Joseph Mezzara, his wife Suzanne Mathilde Leenhoff, and Edouard Manet, see Beth Archer Brombert, Edouard Manet: Rebel in a Frock Coat (Boston: Little, Brown, 1996), 137–38.

[24] Bellier de la Chavignerie and Auvray, Dictionnaire général des artistes de l'école française 2:84, s.v. “Mezzara, Pierre.”

[25] In 1866, his monumental statue of President Abraham Lincoln was unveiled in San Francisco. See Idwal Jones, “Evviva San Francisco,” American Mercury Magazine, September-December 1927, 153–54; and Peter E. Palmquist and Thomas R. Kailbourn, Pioneer Photographers of the Far West: A Biographical Dictionary, 1840–1865 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000), 399.

[26] NYC-HR, 113–18.

[27] For more information on the career of Aaron H. Palmer and his role in United States commercial policy, see Jessica Lepler, “‘The American and Foreign Agency’: Profit and a Prophet of American Commercial Expansion,” a paper submitted to The Twelfth Annual Conference of the Program in Early American Economy and Society, October 11-12, 2012, at 2–3, 5–7, 9, 12–13, 18–22, accessed August 4, 2014, http://www.librarycompany.org/

economics/2012Conference/pdf/PEAES%20--%202012%20conf%20Lepler%20ppr.pdf. I am grateful to Jessica Lepler for her kind permission to cite this source.

[28] NYC-HR, 114.

[29] The front cover of the report lists Daniel Rogers, Counsellor at Law, as the author. The publication of monthly reports in pamphlet form began in 1816. See also John D. Gordan, III, “The Price of Vanity or The Lawyer with the Ears of an Ass,” The Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York 1, no. 2 (Spring-Summer 2004): 6.

[30] See Eugene Volokh, “Symbolic Expression and the Original Meaning of the First Amendment,” The Georgetown Law Journal 97, no. 4 (2009): 1057; and Marianne Constable, The Law of the Other: The Mixed Jury and Changing Conceptions of Citizenship, Law and Knowledge (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1994), 183n10.

[31] Gordan, “Price of Vanity,” 5–6. Gordan used this as a rationale for providing more information about the secondary characters—in particular, the mayor, the painter J. W. Jarvis who was called as a witness, and Edmond Charles Genêt (Versailles, 1763–New York, 1834) who acted as an interpreter. Genêt was a French ambassador to the United States during the French Revolution. After his compromising pro-French activities, violating America’s neutrality in the European conflict (the so called “Citizen Genêt affair” of 1793), Genêt moved to New York, where he married Cornelia Clinton, the daughter of New York Governor George Clinton, in 1794. John Wesley Jarvis painted this governor’s portrait in 1816/1817 (Washington, National Portrait Gallery).

[32] On Aaron Palmer’s many initiatives to promote “global commerce” from the United States, see Lepler, “American and Foreign Agency.”

[33] NYC-HR, 115.

[34] See the inscription on the portrait and NYC-HR, 118. During the trial, the Mayor identified Mezzara as a “Roman artist” and added that “Rome is the seat of the fine arts, the cradle of painting.”

[35] NYC-HR, 114–15. Quinette was described in the proceedings as “Baron Quenette, a French gentleman residing in this city.” On the republican Quinette, who only resided for two years in New York (1816–18), see Julien Sapori, “Nicolas-Marie Quinette: Biographie d’un révolutionnaire soissonnais devenue assez célèbre en des heures peu glorieuses,” Société archéologique et scientifique de Soissons, 47 (2002): 75–119.

[36] “Previous to this, however, he had seen the picture, in an unfinished state, and, expressed no particular disapprobation of the performance to the defendant.” NYC-HR, 115.

[37] Ibid.

[38] “And, at the request of the defendant [Mezzara], gave him a certificate authorizing him to keep the picture.” NYC-HR, 115. The report further states that this document was signed on May 20, 1817. Ibid., 117.

[39] NYC-HR, 114.

[40] NYC-HR, 116. Isaac M. Ely was a prominent businessman and social reformer. See Isaac Ely, An Oration Delivered February 22nd, 1813, in Washington Hall before the Washington Benevolent Society of the City of New York, Early American Imprints, 2nd ser. (New York, Hardcastle & Van Pelt, 1813), no. 28418.

[41] “As they were about leaving the room, he [Mezzara] took chalk and sketched Ass's ears on the head of the picture, threatening to paint them thereon and expose it in Broadway.” NYC-HR, 115. “At the same time he took a piece of chalk, and sketched a pair of Ass’s ears on the head of the picture.” Ibid., 116.

[42] Ibid.

[43] The report continues: “The next time the witness saw the picture, it was in the possession of the defendant [Mezzara], who was exposing it, seemingly in a triumphant manner, in Pine-street, with the appendage of Ass's ears. The witness further stated that it was not a representation of Midas.” Ibid., 115. On Jarvis as a painter, see Harold E. Dickson, John Wesley Jarvis, American Painter, 1780–1840: With a Checklist of His Works (New York: The New York Historical Society, 1949).

[44] In addition to Stuart and Jarvis, John Vanderlyn and John Trumbull also deserve mention. See Bryan J. Zygmont, Portraiture and Politics in New York City, 1790–1825: Gilbert Stuart, John Vanderlyn, John Trumbull, and John Wesley Jarvis (Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag, 2008).

[45] Carrie Rebora Barratt and Ellen G. Miles, Gilbert Stuart, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2005), 290–91.

[46] “in the month of July last.” NYC-HR, 114.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid., 115–16.

[49] Ibid., 116.

[50] “Mr. Palmer having understood, a few minutes previous to the sale, that the picture was so disfigured, instructed the witness to have it bid as $30, for the purpose of having it destroyed, and a young man, a clerk in the auction room, bid to that sum for Palmer.” Ibid., 114.

[51] Ibid.

[52] See Oscar Handlin, “The Bill of Rights in Its Context,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 3rd ser., vol. 104 (1992): 7–8.

[53] NYC-HR, 113–14.

[54] Ibid., 114.

[55] “Samuel Woodworth, a witness on behalf of the prosecution, on being sworn, stated, that he wrote the article, above set forth, and inserted it in the ‘Republican Chronicle,’ from the instructions which he received.” Ibid.

[56] See “The Trial of Francis Mezzara for Libel. New York City, 1817,” in American State Trials: A Collection of the Important and Interesting Criminal Trials Which Have Taken Place in the United States from the Beginning of Our Government to the Present Day, ed. John Davison Lawson (St. Louis: F. H. Thomas Law Book Co., 1914), 1:60, archive.org, accessed October 2, 2014, https://archive.org/stream/americanstatetr06lawsgoog#page/n91/mode/2up

[57] NYC-HR, 116.

[58] Ibid., 117.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid., 116.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid., 118. It is noteworthy that, even so, the first page of the report includes a footnote explaining who King Midas was and what role the donkey’s ears play in his story, with a reference to Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ibid., 113.

[63] Ibid., 118.

[64] “In consideration that he was not a man of property, and was a stranger in our country, (which were mentioned as reasons for not inflicting a more rigorous punishment) [the mayor] proceeded to sentence him to pay a fine of $100.” Ibid.

[65] The fact that Mezzara received a reduction of his punishment implies that he was not familiar with American principles.

[66] See Charles Edwards, Pleasantries about Courts and Lawyers of the State of New York (New York: Richardson & Co, 1867), 52–54; Peter Hay, The Book of Legal Anecdotes (New York: Facts on File, 1989), 100; Barnett Hollander, The International Law of Art, for Lawyers, Collectors and Artists (London: Bowes & Bowes, 1959), 80; and Oscar Handlin, Liberty in America, 1600 to the Present, vol. 2, Liberty in Expansion, 1760–1850 (New York: HarperCollins, 1994), 350.

[67] Volokh, “Symbolic Expression,” 1057.

[68] Ibid., 1071.

[69] Ibid. Volokh quotes the New York Constitution of 1821, art. VII, § 8: “Every citizen may freely speak, write, and publish his sentiments on all subjects, being responsible for the abuse of that right; and no law shall be passed to restrain or abridge the liberty of speech or of the press. In all prosecutions or indictments for libels, the truth may be given in evidence, to the jury; and if it shall appear to the jury that the matter charged as libelous is true, and was published with good motives, and for justifiable ends, the party shall be acquitted; and the jury shall have the right to determine the law and the fact.” Volokh, “Symbolic Expression,” 1071n84. That meant that from 1821 onward, according to the state constitution, every inhabitant of New York State would be responsible for the abuse of the right of free speech. Volokh writes: “The view that symbolic expression is functionally equivalent to verbal expression, and therefore should be treated the same, would logically apply to constitutional speech protections as well as to speech restrictions. And history here tracks logic: several sources from the 1790s to the 1830s, and from several states, suggest that judges and lawyers of that era indeed understood constitutional free speech and free press principles as applying to symbolic expression as well as to verbal expression.” Ibid., 1068. Volokh notes that “just four years after Mezzara’s Case, at the next constitutional convention, the statute’s provisions [which had provided for the same protections and restrictions] were adopted as part of the New York Constitution.” Ibid., 1071.

For the complete text of The Second Constitution of New York of 1821, see Historical Society of the New York Courts, last accessed August 24, 2014, http://www.nycourts.gov/history/legal-history-new-york/history-new-york-courts-constitutions.html. See also: Michael T. Gibson, “The Supreme Court and Freedom of Expression From 1791 to 1917,” Fordham Law Review 55, no. 33 (1986): 280; and Philip A. Hamburger, “Natural Rights, Natural Law, and American Constitutions,” Yale Law Journal 102 (1993): 907–11: “[T]he First Amendment . . . does not forbid the abridging of speech. But, at the same time, it does forbid the abridging of the freedom of speech.” (at 907, quoting Alexander Meiklejohn, Political Freedom: The Constitutional Powers of the People); “[T]he theory of free political expression as a natural right and the concept of seditious libel could not forever coexist” (at 911, quoting Leonard W. Levy, Emergence of a Free Press). In note 15, Hamburger states: “Incidentally, there is relatively little scholarship on the idea of freedom of speech and press in the nineteenth century.”

[70] Volokh, “Symbolic Expression,” 1071. For the original source, see NYC-HR, 117: “This [appendage of the ears of an ass] is urged as a circumstance manifesting the mischievous intention of the defendant.” Furthermore, he published the advertisement “giving an account of the sale of the picture in its disfigured state. This advertisement furnishes, perhaps, the best evidence of his intention in the transformation of this picture.” NYC-HR, 117. See also NYC-HR, 118: “This appendage . . . is incompatible with our ideas of moral fitness.”

[71] NYC-HR, 118. The verdict of the Mayor’s Court was that the portrait was not “such a likeness as Palmer had a right to expect.” See also Floyd F. Miles, “Double Trouble or Never Sue a Lawyer,” DICTA: Knoxville Bar Association; The Official Monthly Magazine, July 1952, 271–72.

[72] Mezzara’s case reminds of a case which occurred in England in 1810. The writer Thomas Hope (1769–1831) had married a very beautiful woman. The painter Antoine Dubost (1769–1825) was asked to paint her picture. He signally failed and her husband refused to receive and pay for the picture. The painter added to the lady’s picture a caricature of her husband and called the portrait “La Belle et la Bête” and had it exhibited in London. One day, the brother of Mrs. Hope destroyed the picture. The artist brought an action against Hope but the jury finally decided that the plaintiff only should be awarded the value of the canvas and paint. See Edwards, Pleasantries about Courts, 54.

[73] Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Artists, trans. Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella (New York: Oxford World's Classics, 1991), 461–62.

[74] “Iaques de Poindre, Discipel van*desen Marcus, welcken laques Suster had ghetrout, was oock een goet Meester, besonder in conterfeyten: van hem was een Altaer-tafel, Crucifix, daer veel conterfeytselen in quamen. Eens had hy gheconterfeyt eenen Enghels Capiteyn, Pieter Andries, een groot brageerder, die t'conterfeytsel hem liet houden sonder betalen: waerom laques uyt onverdult maeckte met Water-verwe voor de tronie een tralie, dat het scheen dat den Capiteyn sat in vangnis, en steldet ten toon. Den Capiteyn dit verhoorende, quam vragen wat hy voor een stuck rabbauts was, sulcx te doen. Hy antwoorde, dat hy dus most ghevangen sitten, tot dat hy betalen soude. Den Capiteyn heeft t'gelt gegheven, en woudet sien uytdoen. Den anderen nam een spongie, en wischtet uyt. Hy heeft veel goede conterfeytselen gedaen; is gereyst in Oostlant oft Denemarck, en daer gestorven A. 1570 of daer omtrent.” Karel van Mander, The Lives of the Illustrious Netherlandish and German Painters, from the First Edition of the Schilder-boeck (1603–1604), ed. Hessel Miedema (Doornspijk: Davaco, 1994), 1:172–73 (Dutch text and translation into English); and (1996), 3:186–88 (Commentary).

[75] The quotations are from this anecdote: “Dat hy seer vermaeckelijck in manieren ende spraeck was, canmen bewijsen uyt een vremde actie die hy ghespelt hadde aen seker Edelman die van Mostaert was uytgheschildert seer constich en wel ghedaen dat de spraeck en leven in 't Conterfeytsel maer en ontbraken. Dan den Edelman door hooverdy ontsteken sijnde, was de kunst verachtende en seyde dat hy in 't pourtret niet en gheleeck, dat het te bruyn was, en soo Mostaert 'tselve niet en wilde verbeteren, dreyghde hem 'tselve aende handt te laten. Desen Mostaert dit liedeken niet geren hoorende ter wylen hy ghewoon was naer het werck gelt te ontfangen om de weerdinne den penninck te gunnen, en cost in het stuck niet vinden als een volle perfectie, en denckende datter veele Menschen waeren die soecken gheflateert te worden en(de) ghepluymstrijckt, heeft ghelooft de Troni te veranderen, hoe wel hy daer aen niet en toestste maer wist om het hooft een geestighe Sots-cap met water verf te schilderen, settende alsoo het stuck dagelijkcks voor sijne deure ende alsoo den Edelman inde stadt ghenoech bekent was, waren alle de passanten seer verwondert siende sulcken treffelijck Man met een Sots-cap ende 'tselve aen hem ghewaerschouwt zijnde, is met grammen moede naer het huys vanden Schilder gecomen om oock sijn eygen af-beltsel inde figure van eenen Sot te sien en 't selve siende, wert insulcken colair ontsteken dat (by soo verre Mostaert hadde onder sijn ooghen gheweest) hy den selven sou 'tleven ghenomen hebben, ende naer denselven vragende, wert geroepen, den welcken terstont sonder eenighe ontsteltenis ende met een ongeployt aenschijn (siende den Edelman, wist sonder vraghen wat hy begeerde) ende daer by comende vraeghde den Edelman vyt wat reden hy hem ghelijck eenen Sot hadde gheschildert, ende alsoo ghelijck eenen Sot noch voor sijn deur op straet ten thoon stelde, sulcks dat hem alle de wereldt kende: heeft Mostaert terstont daer op met een statich wesen gheantwoort verwondert te sijn dat hy sijn selven nu was kennende ter wijlen hy de Sots-cap aen hadde, en dat hy sijn selven niet en kende als hy ghelijck een wijs Man gheschildert was.” Cornelis de Bie, Het gulden cabinet van de edel vry schilderconst (Antwerp: Jan Meyssens, 1662), 83–84.