The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

I was going to tell you last time . . . about a sort of break that came in my work about 1883. I had wrung Impressionism dry and I finally came to the conclusion that I knew neither how to paint nor how to draw. In a word, Impressionism was a blind alley as far as I was concerned.

—Ambroise Vollard, quoting Pierre-Auguste Renoir[1]

Theories abound about Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s (1841–1919) “crisis of Impressionism” in the second quarter of the 1880s, when he adopted an idealist style based less on direct observation of the world, and more on the art of the past.[2] A study of Renoir’s complicated relationships with wealthy high-society Jewish patrons from 1878 to 1881, offers new perspective on this stylistic transformation, from Renoir’s Impressionist phase to what has been called his “Ingresque” or “dry” manner.[3] Although the “break” in Renoir’s work occurred two years after his break with the Jewish patrons, I argue that their ideas about art continued to influence him for more than a decade. This is particularly true of the strong preference, within the Jewish milieu, for eighteenth-century and Old Master art, which Renoir shared in the 1880s and 1890s. Renoir’s contact with wealthy Jewish patrons explains some of the changes he made in his exhibition policy, and it may, as well, have been a contributing factor in his adoption of a more classical, idealist style.

Renoir became involved with Paris’s circle of wealthy Jewish patrons in 1878 through Charles Ephrussi (1849–1905), the art historian and critic who was the subject of Edmund de Waal’s recent book, The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Family’s Century of Art and Loss.[4] Perhaps believing that his best chance at gaining financial, critical, and popular success was in the hands of these new patrons, Renoir dedicated much of 1880 and 1881 to painting portraits of Ephrussi’s friends and family. By the end of 1881, however, the artist fell out with Ephrussi and his circle and renounced them. Shortly thereafter, Renoir suffered his “crisis of Impressionism,” declaring that he had “wrung Impressionism dry” and could no longer “paint nor draw.” The two incidents were linked, and when Renoir mapped a new path for his career in 1883, he did so with his former Jewish patrons in mind, considering their taste, advice, and demands. A close study of Renoir’s portraits of his Jewish patrons, particularly of the Cahen d’Anvers family, will contribute to our understanding of the reasons behind Renoir’s break with Impressionism, as well as the new direction his career took after 1883.

In late 1878, Renoir introduced himself to Charles Ephrussi with an invitation to preview Madame Charpentier and her Children before it was exhibited at the Salon of 1879.[5] Ephrussi was a widely respected art historian and a prominent society figure with influence in both the Jewish and aristocratic salons of Paris. By the early 1880s, Ephrussi was internationally known for both his scholarship and socializing.[6] One British society columnist, in an article entitled “Jews in Paris,” reported on Ephrussi’s circle of artistically-minded high-society friends and family:

Through the loophole of art, one of these energetic Israelites (Charles Ephrussi) penetrated the salon of an ex-imperial highness (Princess Mathilde). He made room for his uncles and aunts and cousins, who gradually introduced their friends and their friends’ friends, until at last the Wednesday receptions of the amiable hostess . . . have come to be in large degree receptions of the descendants of the tribes.[7]

While the tone of the British article was disapproving, it was true that Ephrussi and his circle used art as a means of gaining acceptance into the highest echelons of French society.

Renoir, who had been campaigning to obtain a state commission for the decoration of a public building, was likely aware that Ephrussi had considerable influence in the realms of museum and government art administration.[8] It was widely rumored that Ephrussi had secured the recent commissions for Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and Elie Delaunay to decorate the Pantheon and Hôtel de Ville.[9] Furthermore, Ephrussi was a main contributor to the Gazette des beaux-arts, an influential art journal that he would later own in the 1890s.[10]

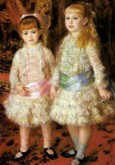

Ephrussi was impressed with the Charpentier portrait, and began to recruit his friends and family to sit for Renoir. The first portrait of a member of the Ephrussi circle dates to July 1880, when Renoir painted Charles’s aunt, Madame Léon Fould, née Thérèse Prascovie Ephrussi (1851–1911) (fig. 1). At the same time, Thérèse’s mother-in-law, Madame Eugène Fould, née Delphine Marchand (1812–88), and the young Fernand Halphen (1872–1917), an Ephrussi cousin, sat for the artist (figs. 2, 3). Also in the summer of 1880, Charles convinced his mistress, Louise Cahen d’Anvers (1845–1926), to commission a portrait of her eldest daughter, Irène (1872–1963) (fig. 4).[11] Pleased with the work, Madame Cahen d’Anvers commissioned a double portrait of her younger daughters, Elisabeth (1874–1945) and Alice (1876–1965), which was finished in February of 1881 (fig. 5). By August 1880, Renoir and Ephrussi were so close that the artist entrusted the critic with organizing his submission to the Salon of 1881 while he was in Algeria.[12] Renoir commemorated his friendship with Ephrussi in Luncheon of the Boating Party, in which Ephrussi appears in the back of the group, wearing a top hat (fig. 6).

Degas was disappointed with what he saw as Renoir’s transformation into a Jewish-society portraitist. In 1880, he wrote:

Monsieur Renoir, you have no integrity. It is unacceptable that you paint to order. I gather you now work for financiers, that you do the rounds with Charles Ephrussi. Next you’ll be exhibiting at the Mirlitons with Bouguereau![13]

Shortly thereafter, Renoir’s burst of activity as a society portraitist ended.[14] He painted his last portrait of an Ephrussi-circle patron in the fall of 1881, when Albert Cahen d’Anvers (1846–1903) sat for him at Paul Bérard’s (1833–1905) country estate (fig. 7).[15] By winter, Renoir was complaining about the conventional tastes of his Jewish patrons, scornfully invoking the names of Léon Bonnat and Gustave Moreau, whose work the Ephrussi circle enthusiastically collected. However, even as he rejected his high society Jewish patrons, he struggled to develop a style that suited both his aims as an artist and the tastes of wealthy collectors like them. To his dealer, Paul Durand Ruel, he wrote, “I want to make marvelous paintings for you, that you can sell for a lot of money. I wish for you many rich amateurs.”[16]

Renoir’s Cahen d’Anvers Portraits and his Break with the Ephrussi Patronage Circle

When Renoir turned to Charles Ephrussi in 1878, he had recently decided to abandon the annual Impressionist exhibitions and resume submitting paintings to the official Salon. For the next several years, he struggled to distance himself from the Impressionists and tried to understand how to please the critics and public as he prepared for the annual exhibitions.[17] In 1881 he explained to Durand-Ruel that his new strategy would be to exhibit two portraits at the Salon every year in order to attract new patrons.[18] In anticipation of the 1881 Salon, Charles Ephrussi advised Renoir to submit two of his Jewish-society portraits, Irène Cahen d’Anvers and The Cahen d’Anvers Girls (figs. 4, 5).

The Cahen d’Anvers family deserves a great deal more scholarly attention than it has received, particularly from art historians. They were among the wealthiest and most noteworthy families in Paris during the fin-de-siècle, and in many ways their patronage practices were typical of Jewish high society. They were dedicated to collecting the art of the French eighteenth century, and dabbled in japonisme when it was at the height of its popularity in the 1870s. Members of the Cahen d’Anvers family commissioned portraits from Salon and independent artists, and collected both modern and Old Master paintings. Like many Jewish patrons, their intense interest in preserving French patrimony led them to bequeath their homes and collections to the state. Despite their wealth and cultivation, their religion made them lightning rods for controversy even before the Dreyfus Affair.[19]

The women of the Cahen d’Anvers family took the initiative in matters of art, and were largely responsible for the artistic and literary tone of their families’ salons.[20] The salons juifs of the Belle Epoque became a patronage network in which women fostered connections, introducing artists to patrons, sympathetic critics, and potentially inspiring musicians, writers, actors, and socialites. In the salons juifs, the patronage of modern art became a rallying point and a marker of identity that preserved and refashioned a distinct Jewish sphere.[21]

Louise Cahen d’Anvers, who was married to the banker Louis-Raphael Cahen d’Anvers, commissioned the portrait of her daughter Irène in 1880.[22] Louise was Charles Ephrussi’s mistress in the late 1870s and 1880s, and the affair seems to have been fairly common knowledge. In 1878, Edmond de Goncourt delighted in spying on an illicit rendezvous between “la Cahen d’Anvers” and Ephrussi at Sichel’s gallery.[23] As one of the group of women dubbed the “Jewesses of art” by the artist Jean-Louis Forain, Louise was a subject of both repulsion and fascination for Goncourt, who described her as a medusa-like figure.[24] She and her sister-in-law, Marie Kann, were the mistresses of Paul Bourget, and the muses of Guy de Maupassant. Louise was a major patron of music, literature, and art, and sat for portraits by Carolus-Duran, Paul Baudry, and Léon Bonnat.[25]

Renoir believed that his portrait of Irène was a triumph even before it was shown at the Salon of 1881.[26] Ephrussi agreed, and asked Renoir to make an etching of the portrait to be included in the Gazette des beaux-arts’s Salon review (fig. 8). At the Salon Irène Cahen d’Anvers garnered some positive attention. Joris-Karl Huysmans was enthusiastic, writing:

The portraits that [Renoir] exhibits in the present Salon are charming, particularly one of a little girl in profile, which is painted with a flourish of color that has only ever been approached by the old masters of the English school. Curiously passionate about the reflection of the sun on the velvety skin, the play of the rays over the hair and the fabric, M. Renoir bathed his figure in true light and one sees the adorable nuances, the iridescence that blooms on the canvas! These works figure, absolutely, among the most sumptuous at the Salon.[27]

Ernest Chassagnol wrote:

One cannot dream of anything prettier than this blond child, whose hair unfolds like a sheath of silk bathed with shimmering reflections and whose blue eyes are full of naïve surprise.[28]

Huysmans and Chassagnol had embraced what Edmond Duranty called the “New Painting,” and both critics emphasize the Impressionist qualities of the portrait, particularly the play of light on the sitter’s hair, clothing, and skin. In his portrait of Irène, Renoir rendered light in a way that was meant to suggest that he was painting out-of-doors, an illusion that is reinforced by the leafy backdrop. The dynamic natural lighting is apparent in the background and on the sitter’s hair, where color fades to black or white depending on the intensity of the light. The similarity of the treatment of Irène’s hair and the foliage integrates the figure and ground. The sitter’s features are relatively undefined, and the outlines of her body and face are hazy, suggesting the effects of bright sunlight. While Renoir did not take his Impressionist rendering of a body en plein airas far as he did in, for example, Torso, Effect of Sunlight of 1876 (fig. 9), the portrait of Irène has more in common with the artist’s work of the mid-eighteen-seventies than with the Fould and Halphen portraits of 1880.

Louise Cahen d’Anvers seems to have been pleased with the portrait of her daughter, because in the fall of 1880, Renoir was enlisted to paint a double portrait of her younger daughters, Elisabeth and Alice (fig. 5).[29] Barbara Ehrlich White argues that this work, referred to as The Cahen d’Anvers Girls or Pink and Blue, caused Renoir to become “dissatisfied with Impressionism for figures because of its formlessness.”[30] As evidence of his discomfort with its style, she cites a letter that Renoir wrote to Théodore Duret during the 1881 Salon, in which he stated: “I have at the Salon the portraits of the little Cahens. I do not know if they will have the same deplorable effect as the works at last year’s exhibition.”[31] It is more likely, however, that Renoir’s letter to Duret reflected his confusion and frustration with public and critical taste. Despite the few positive reviews from Salon critics, Renoir’s fears were realized when the Cahen d’Anvers family expressed their disappointment with the work by refusing to pay for it.[32]

The Impressionist style of the work could not have come as a surprise to Louise Cahen d’Anvers. The short multicolored brushstrokes on the lacy dresses, the dappling on the satin ribbons, and the lack of strong contour lines were similar to those in the portrait of Irène. As in many of his society portraits of the period, Renoir employed formal composition and conventional poses, and rendered the figures in detail. The Cahen d’Anvers girls do not dissolve or merge with the background like Renoir’s earlier Impressionist figures, but are skillfully modeled. The dresses of the little Cahen girls are masterpieces of Impressionist fabric, and the figures are at once solid and dynamic. Despite the substantiality of the figures, the painting retains the lively surface design of Impressionism that suggests light flickering over the girls’ faces and bodies. The fabric of their dresses floats at the center of the composition, glowing as if lit from within, and the ethereality of the lace and satin is heightened against the background of dark red and gold fabric. A bright light rakes the dresses, emphasizing their texture, and casting yellow shadows on their folds. The shiny satin of the girls’ sashes, rendered with touches of green, white, blue, purple, and pink, reflects the colors of their arms and sleeves. Renoir’s debt to Impressionism is apparent in these diaphanous lace dresses that vibrate with color, both of skin and petticoats peeking through the open weave of the fabric, and of the light and shadow of the room.

The faces and hair of the figures are painted in a manner that blends traditional principles of painting with Impressionist technique. Alice’s smooth pale face and rosy cheeks are enlivened by her eyes, which are rendered in an impressive variety of shades of blue, white, green, and black. Alice’s chestnut hair and Elisabeth’s strawberry blond curls are masterfully executed in tones of red, brown, yellow, white, orange, and black. The skin of the girls’ hands and legs is more characteristic of Renoir’s Impressionist experiments with color, but retains the naturalism appropriate for a portrait. The composition of the work and the girls’ poses reflect Renoir’s admiration of Velazquez’s portraits of the Infanta Margarita.[33] The curtain and rug in the background of the painting are also recognizably in the tradition of Old Master portraiture, although the lack of distinction between the wall and the floor renders the picture-space somewhat undefined.

Renoir had originally hoped that the Cahen d’Anvers family would commission individual portraits of Alice and Elisabeth, but they asked for the girls to be painted together in late 1880.[34] The change in concept was fortuitous, because the double portrait is an outstanding example of Renoir’s affectionate and sensitive depictions of children. The girls are endearingly individualized. Alice, on the left, pouts slightly, and seems to be on the verge of tears as she nervously thumbs her pink sash. In an interview with the historian Philippe Jullian many years later, Alice recalled “the boredom of the portrait sessions,” which Renoir seems to have captured in her expression.[35] Elisabeth, smiling and poised, holds Alice’s hand and daintily lifts the edge of her skirt, proudly showing off her dress. Alice’s tilted head and wide stance suggest that she is pulling away from her sister, ready to escape from the room.

When the Salon of 1881 ended, Louise Cahen d’Anvers made it clear that she was not pleased with the double portrait of Alice and Elisabeth, immediately banishing it to the maids’ quarters of their home and failing to pay for it for at least a year.[36] In her old age, Alice, then Lady Townsend of Kut, reported to Jullian that her mother eventually gave the portrait to a charitable organization. By way of explanation, Alice added: “My parents were very conventional. They hung Nattier Nymphs and portraits by Bonnat on the [eighteenth-century] wood paneling of their salon.”[37]

Renoir was exasperated with the Cahen d’Anvers family and, as a February 1882 letter from the artist to Charles Deudon suggests, possibly with all of his Jewish patrons. He wrote:

As for the 1500 francs from the Cahens, I must tell you that I find it hard to swallow. The family is so stingy; I am washing my hands of the Jews.[38]

Jewish Taste and Renoir’s New Style

Over the course of the next year, Renoir wrote a succession of angry letters expressing his disdain for Jewish patrons, and he severed all ties with the Ephrussi patronage circle.[39] In March 1882, Renoir focused his anger on Charles Ephrussi. Having traveled again to Algeria that month, he placed the responsibility of submitting his works to the Salon of 1882 in the hands of Paul Bérard, a task that he had entrusted to Ephrussi with positive results only a year earlier.[40] In early March, Renoir advised Bérard to send his portrait, Paul Bérard, to the Salon against the advice of Charles Ephrussi. He wrote:

Now let’s talk art. I told [Charles] Deudon what I thought of Ephrussy [sic] as an art critic. I beg you not to listen to him . . . Maybe your portrait is too strong for him, that’s the reason. . . . If Charles could be prevailed upon to buy frames for his pictures that cost more than 3 livres 10 sous, we could have shown the little girl from Berneval.[41]

“The little girl from Berneval” was Gypsy Girl, a painting that Ephrussi bought from Renoir in 1879.[42] Not only was “Ephrussy’s” opinion no longer of any value to Renoir, but the artist believed that his former patron’s stinginess was preventing him from sending his best works to the Salon. The next day, Renoir reversed his opinion about sending Paul Bérard to the Salon, writing to Bérard with disgusted resignation:

Don’t follow my advice and listen to Ephrussy. That man, more Jew than bourgeois, has the right eye for the so-called (hairdresser’s) Salon. . . . But it has to be done, and I told you, I don’t care.[43]

Ultimately, Renoir was represented in the Salon of 1882 by just one work, his small portrait of Yvonne Grimpel, painted in 1880.

In 1882, Renoir equated the Salon with “Jewish” taste, and when he washed his hands of the Jews, he was also rejecting the “beauty Salon.” Renoir’s belief that Jewish taste predominated at the Salon becomes even more evident in his comments about his fellow painters, Léon Bonnat and Gustave Moreau. Both artists were closely associated with the Ephrussi circle, which had been enthusiastically collecting and commissioning their work for decades. After his falling out with the Cahen d’Anvers family, Renoir vowed not to compromise his integrity any further in pursuit of Jewish patrons or the Salon, and he expressed disgust at Bonnat and Moreau for catering to his former patrons. In the fall of 1882, Renoir wrote to Bérard sarcastically:

I must return to the true path of painting and I have decided to enter Bonnat’s studio after all. In a year or two, I’ll be earning 30,000,000,000,000 francs a year. And don’t ever mention portraits in the sunshine to me again. A good black background, that’s the ticket![44]

As he renounced his Jewish patrons, and his anti-Semitic remarks became more frequent, Renoir’s wrath was directed at the artist most commonly associated with Jewish high society. Bonnat painted almost every member of the salons juifs, including Albert and Louilia Cahen d’Anvers, Charles Ephrussi, Marie and Edouard Kann, Louise Cahen d’Anvers, Mme Leopold Stern, Mme Bischoffsheim, Countess Potocka, Joseph Reinach, Abraham de Camondo, and Henri Cernuschi. Like many society portraitists, Bonnat and his wife became members of high society, particularly the world of the salons juifs.

In the twentieth century, Jacques-Emile Blanche recalled the affinity of “wealthy Jewish financiers” for Bonnat. Blanche was correct in asserting that it was Bonnat, and not Renoir, who was truly the portraitist of Jewish high society. Blanche explained that Renoir’s Jewish patrons were “not at all convinced of [Renoir’s] talent” but were promised by Ephrussi “enormous returns on the sale of Impressionist pictures.”[45] Accusing Jewish art patrons of speculation was a common trope of anti-Semitic discourse, and Blanche’s tone was demeaning when he described Ephrussi’s circle as “rather proud of their audacity” in commissioning portraits from Renoir that ultimately “ended up in the laundry room or were given away to former governesses.”[46]

Bonnat was not the only artist on Renoir’s mind during his “crisis of Impressionism.” He was also thinking about Gustave Moreau, who had enjoyed success in Parisian high society for many years, particularly among Jewish patrons.[47] Albert Cahen d’Anvers and Charles Ephrussi had been enthusiastic supporters of the artist since the early eighteen-seventies.[48] Vollard remembers Renoir’s resentful comments about Moreau:

It is incredible that Gustave Moreau could have been taken seriously! Why, he could not even draw a foot! They talk so much about his scorn for the world. . . . But he certainly knew what he was about when he conceived the idea of painting with gold colors to take in the Jews! He even fooled Ephrussi, who I thought had more sense than that. I went to Ephrussi’s house one day and the first thing I laid my eyes on was a Gustave Moreau.[49]

As Renoir contemplated a new direction in his career, his experiences with Jewish patrons colored his thinking. While apparently rejecting their taste, he also took it into account, because he realized that they were among the most important and wealthy patrons of the period.

Renoir continued to be peripherally associated with Ephrussi and informed by his ideas. Indeed, the artist and his former patrons shared many interests in the 1880s. In the winter of 1881-82, Renoir travelled to Italy for the first time. It is likely that before their falling out, Ephrussi, who visited the country frequently and wrote extensively on Italian art, advised Renoir on what to see on his trip. In those years, Ephrussi was particularly interested in Raphael, whose frescoes Renoir sought out in Rome.[50] While the artist’s enthusiasm for the Old Masters was far from overwhelming and he made no copies while in Italy, he admitted that Raphael’s works were “very beautiful, and I should have seen them earlier. They are full of wisdom and knowledge.”[51] Ephrussi may also be linked to Renoir’s interest in other Old Masters in the 1880s. After a decade of research, Ephrussi published an important monograph on the drawings of Albrecht Dürer in 1882 with the assistance of the future theorist of Impressionism, Jules Laforgue.[52] John House has suggested that Renoir was influenced by the work of Dürer in this period.[53]

In his article on the Large Bathers of 1887, House also suggests that Renoir’s interest in the art of the eighteenth century may have been connected to Charles Ephrussi.[54] House argues that Renoir’s ideas about the decorative arts, which he enumerated in an article entitled “Society of Irregularists” in 1884, were strikingly similar to those of the Central Union of Decorative Arts, of which Ephrussi was a founding member in 1882.[55] Both Renoir and the Central Union idealized the eighteenth century, believing that it had produced great art because there had been little distinction between designer and producer and artist and artisan. In 1885, Renoir explained his new interest in the eighteenth century to a perplexed Durand-Ruel:

I have gone back to the old painting, the gentle light sort and I don’t intend to ever abandon it again. . . . My work is quite different from the last landscapes and that dull portrait of your daughter . . . it is not so much new, as a continuation of eighteenth-century painting. I don’t mean the very best of course, but I am trying to give you a rough idea of this new (and final) style of mine (A sort of inferior Fragonard). . . . Please understand that I am not comparing myself to an eighteenth-century master, but it is important to try and explain to you the direction in which I am moving.[56]

Few Belle Epoque collectors were more enthusiastic about the eighteenth century than the men and women of Jewish high society. The Ephrussi and Cahen d’Anvers families consciously emulated the social and behavioral models of ancien régime aristocracy. They hosted intellectual salons, bought châteaux in the French countryside, employed liveried servants, and hunted. It is the general consensus of scholars of Jewish history that this reflected Jewish patrons’ desire to make a claim on France as a homeland.[57] Owning objects from what was considered to be the golden age of French art and culture spoke to Jewish patrons’ longing to fully assimilate into French high society. Wealthy Jewish immigrants, many of whom had arrived in Paris after the Franco-Prussian War, took advantage of the fact that objects that reflected French heritage and tradition were for sale. The most notable Belle Epoque Jewish patron of eighteenth-century art and objects was Irène Cahen d’Anvers’s first husband, Moise de Camondo, whose home was bequeathed to France as the Musée Nissim de Camondo. This monument to the art of the late eighteenth century, modeled on the Petit Trianon, was painstakingly curated by Camondo in authentic Louise XVI style. In 1895, Louis and Louise Cahen d’Anvers bought the Château de Champs-sur-Marne, the one-time home of Madame de Pompadour, built in 1699.[58] The couple spent the rest of their lives restoring the château to its eighteenth-century splendor, based on its original plans. They reconstructed the terraced French gardens that had been replaced by an English garden sometime in the nineteenth century, imported rococo boiseries from the Hotel de Mayenne in Paris, and commissioned copies of large-scale sculptures from the gardens of Versailles.[59] Their painting collection included portraits of Louis XIV as a child, a full-length portrait of Louis XV, and Reynolds’ portrait of Anne Montgomery. Their son bequeathed the chateau to the state as a museum in 1935.[60]

When Renoir decided to unveil the Large Bathers (fig. 10), he did so at the Galerie Georges Petit rather than at the gallery of his loyal dealer or the official Salon.[61] The Galerie Georges Petit was the most elegant exhibition space in Paris and attracted the richest patrons. Jacques-Emile Blanche, who was among the gallery’s regular exhibitors, described Charles Ephrussi as the éminence grise (“person secretly in charge”) of Petit’s gallery.[62] It was Ephrussi who convinced Petit to promote fashionable middle-of-road contemporary artists at an annual International Painting Exhibition, and Petit and Ephrussi collaborated on exhibitions of eighteenth-century art.[63] Among their more notable shows was one touted as the “apotheosis” of Fragonard, Watteau, and Boucher in 1883.[64] In 1886, Renoir exhibited several works at Petit’s Fifth International Exhibition, and in 1887, decided to finally unveil his Large Bathers at the Sixth International. He explained to Durand-Ruel that he chose this venue because he had painted the bathers with the haut bourgeois who frequented Petit’s gallery in mind, declaring, “I think I have made a step in public esteem.”[65] Indeed, exhibiting in the same context as the most marketable contemporary artists and the masters of the eighteenth century offered some credibility to Renoir’s new work.

Many years after Renoir broke with Ephrussi and his circle, Marcel Proust remembered their short relationship. In volume three of In Search of Lost Time, the novel’s narrator discusses Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party with the Duc de Guermantes. In regard to the figure in the top hat, Charles Ephrussi, the Duc explains:

I know that it is a fellow who is quite well known and no fool either in his own line. . . . What I can tell you is that the gentleman you mean has been a sort of Maecenas to Elstir. He gave him a start and has often helped him out of tight places by ordering pictures from him. As a compliment to this man- if you can call that sort of thing a compliment- he has painted him standing among that crowd.[66]

Renoir relied on Ephrussi as a Maecenas for several years. Ephrussi attracted new patrons, bought works, and advised Renoir’s career choices, but Ephrussi’s influence was likely more profound and longer-lasting than his relationship with the artist. While Renoir claimed to reject the taste of his former Jewish patrons, he cultivated many of the same interests as they did throughout the decade. He declared his intention to be “a sort of inferior Fragonard” at a time when Jewish patrons were building the greatest collections of eighteenth-century French art in the world, and the Central Union was promoting the ideals of the eighteenth century. When he travelled to Italy, Renoir paid special attention to the artists favored by the editor of the Gazette des beaux-arts and might have been influenced by the work of Dürer when Ephrussi’s monograph on the artist was published in 1882.[67] Finally, when Renoir chose to unveil his new style in 1887, he did so at a gallery with which Ephrussi was closely associated. These decisions suggest that Renoir was not able to break entirely with his Jewish patrons, whose taste, even after their falling out, continued to inform his work.

[1] Ambroise Vollard, Harold L. Van Doren, and Randolph T. Weaver, Renoir: An Intimate Record (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1925), 56.

[2] Authors who have discussed Renoir’s “crisis of Impressionism” include: Christopher Riopelle, “Renoir: The Great Bathers,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 86, no. 367-68 (Autumn 1990): 2–40; Linda Nochlin, Bathers, Bodies, Beauty: The Visceral Eye (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006); Barbara Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters (New York: Abrams, 1984), 126; Barbara Ehrlich White, “The Bathers of 1887 and Renoir’s Anti-Impressionism,” Art Bulletin 55, no. 1 (March 1973): 106–26; and John House, “Renoir’s ‘Baigneuses’ of 1887 and the Politics of Escapism,” Burlington Magazine 134, no. 1074 (September 1992): 578–85.

[3] The term “Ingresque” is widely used to describe Renoir’s work from this period. Among the historians who refer to Renoir’s “Ingresque” period are John Rewald, Renoir Drawings (New York: Bittner and Co., 1946); and Anne Distel, Renoir: A Sensuous Vision (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1995).

[4] Edmund de Waal, The Hare with Amber Eyes: A Family’s Century of Art and Loss (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2010).

[5] Anne Distel, “Charles Deudon (1832–1914) collectionneur,” Revue de l’art 86 (1989): 59. In November 1878, Renoir asked for Marguerite Charpentier’s permission to bring Charles Ephrussi to her home to see his new work. In his letter, Renoir referred to Ephrussi as a “close friend of Léon Bonnat,” and informed her that he would be accompanied by the collector Charles Deudon. Quoted in Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters, 87.

[6] Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, entry for June 11, 1881, Journal, Mémoires del la Vie Littéraire, vol. 6 (Paris: Bibliothèque-Charpentier, 1906). Edmond de Goncourt accused Charles Ephrussi of “attending six or seven soirées every night in order to become Director of Beaux-Arts.”

[7] Theodore Child, “Jews in Paris,” Fortnightly Review 45 (January-June, 1886): 486.

[8] Auguste Renoir, "L’Art décoratif et contemporaine," L’Impressioniste, April 4, 1877; Robert L. Herbert, Nature’s Workshop: Renoir’s Writings on the Decorative Arts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 64; and Jean Renoir, Renoir, My Father (Boston: Little, Brown, 1962), 135. In 1877 Renoir published an anonymous article in L’Impressioniste calling for more pleasing decorative programs in French buildings. [Pierre-Auguste Renoir], “L’art décoratif et contemporain,” L’Impressionniste 3, April 27, 1877, 3–6. In August or September of 1880, he asked Georges Charpentier for assistance in gaining a public commission, but neither Charpentier nor Eugène Spuller were able to help the artist. Jean Renoir attested to his father’s devastation when President Léon Gambetta informed Renoir that his style was too revolutionary for the decoration of the Hôtel de Ville in 1878. Charles Ephrussi was close to the powerful Louvre curator, Vicomte Both de Tauzia, and would be a founding member of the Central Union of Decorative Arts in 1882. See Auguste Marguiller, "Charles Ephrussi," Gazette Des beaux-arts 3, no. 34 (1905): 355–60 for a full analysis of Charles Ephrussi as an art critic and historian. Marguiller wrote this article to commemorate Ephrussi’s death in 1905.

[9] Jacques-Emile Blanche, La Pêche aux souvenirs (Paris: Flammarion, 1949), 174.

[10] Hélène de Givry, “Charles Ephrussi,” in Dictionnaire critique des historiens de l’art actifs en France de la Révolution à la Première Guerre mondiale, ed. Philippe Sénéchal and Claire Barbillon, Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art, INHA, published September 25, 2009, http://www.inha.fr/spip.php?article2310#haut.

[11] Philip G. Nord, Impressionists and Politics: Art and Democracy in the Nineteenth Century (London: Routledge, 2000), 60.

[12] Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters, 289.

[13] Quoted in de Waal, Hare with Amber Eyes, 83.

[14] Paul Bérard continued to commission portraits of his children, but by 1883, he complained to Charles Deudon about the difficulty he was having convincing his friends to commission portraits from Renoir.

[15] Kathleen Adler, “Renoir’s ‘Portrait of Albert Cahen d’Anvers,'” J. Paul Getty Museum Journal 23 (1995): 31.

[16] Barbara Ehrlich White, “Renoir’s Trip to Italy,” Art Bulletin 51, no. 4 (December 1969): 338.

[17] Colin B. Bailey and John B. Collins, Renoir's Portraits: Impressions of an Age, exh. cat. Ottowa: The National Gallery of Canada (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 1.

[18] Adler, “Renoir’s ‘Portrait of Albert Cahen d’Anvers,'” 33.

[19] As early as 1876, Le Figaro delighted in exposing Louis Cahen d’Anvers's pretensions in adding the d’Anvers to his name. The article, entitled “The Rage for Titles,” was later translated and republished in the New York Times. “The Rage for Titles,” New York Times, April 24, 1876.

[20] For information on the salons juifs, see Emily D. Bilski, Emily Braun, and Leon Botstein, Jewish Women and their Salons: The Power of Conversation, New York: Jewish Museum under the auspices of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005).

[21] While the connection between Jewish high society and modern art was commonly acknowledged during the Belle Epoque, art historians have not yet produced a study of Jewish patronage of modern art before 1914 in France. This is surprising because a disproportionately large number of the early patrons of modern art, particularly Impressionism, were Jewish, and their impact on the history and interpretation of modernism was profound. Several scholars have attempted to explain why such a large percentage of patrons and collectors of modern and avant-garde art were Jewish. Veronica Grodzinski, “Longing and Belonging: French Impressionism and Jewish Patronage,” in Longing, Belonging, and the Making of Jewish Consumer Culture, ed. Gideon Reuveni and Nils H. Roemer (Boston: Brill, 2010), 91–112, explores the patronage of Impressionism by Jewish collectors in Germany. Philip Hook, The Ultimate Trophy: How the Impressionist Painting Conquered the World (New York: Prestel, 2009) also focuses on Impressionism in Germany as does Elana Shapira, “Jewish Identity, Mass Consumption, and Modern Design,” in Reuveni and Roemer, Jewish Consumer Culture. Bilski, Braun, and Botstein, Jewish Women and their Salons studies Jewish high society and culture, focusing particularly on literature.

[22] Bailey and Collins, Renoir’s Portraits, 181.

[23] Edmond de Goncourt and Jules de Goncourt, entry for October 16, 1878, Journal, Mémoires de la vie littéraire, vol. 2.

[24] The following historians attribute the term “Jewesses of Art” to the painter Jean-Louis Forain, who was known for his passionate anti-Semitism: Philippe Jullian, Dreamers of Decadence: Symbolist Painters of the Eighteen-Nineties (London: Pall Mall Press, 1971), 65; Peter Quennell, ed., Marcel Proust, 1871–1922: A Centennial Volume (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1971), 57; Michael de Cossart, Ida Rubinstein (1885–1960): A Theatrical Life (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1987), 11; and Vicki Woolf, Dancing in the Vortex: The Story of Ida Rubinstein (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic, 2000), 16.

[25] Myriam Chimènes, Mécènes et Musiciens: Du Salon au Concert à Paris sous la IIIe République (Paris: Fayard, 2004), 569.

[26] Bailey and Collins, Renoir’s Portraits, 181. Renoir wrote to Charles Ephrussi in August 1880 to tell him that he wanted the portrait of Irène to appear in the Salon of 1881.

[27] Joris-Karl Huysmans, "Le Salon de 1881,” in L'Art Moderne (Paris: G. Charpentier, 1883). My translation.

[28] Ernest Chassagnol, “Le Salon,” Gil Bas, June 10, 1881. My translation.

[29] Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters, 108.

[30] Ehrlich White, "Renoir's Trip to Italy," 335.

[31] Ibid., 338.

[32] Bailey and Collins, Renoir's Portraits, 181.

[33] Anne Distel, Renoir (New York: Abbeville Press, 2010), 21.

[34] Bailey and Collins, Renoir’s Portraits, 181.

[35] Philippe Jullian, “Rose de Renoir, Rétrouvée par Philippe Jullian,” Le Figaro Litteraire, December 22, 1962.

[36] Bailey and Collins, Renoir’s Portraits, 181.

[37] Philippe Jullian, “Rose de Renoir.”

[38] Renoir to Charles Deudon, from L’Estaque, February 19, 1882, quoted in Bailey and Collins, Renoir’s Portraits, 307.

[39] For historians studying Renoir in the 1880s, it might be useful to explore Renoir’s rejection of these patrons, because it was linked to his loss of faith in the Salon as a means to a successful and fulfilling career.

[40] Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters, 124.

[41] Renoir to Bérard, March 1882, quoted ibid.

[42] Bailey and Collins, Renoir’s Portraits, 168.

[43] Renoir to Paul Bérard, undated, mid-March 1882, quoted ibid., 345. My translation.

[44] Renoir to Paul Bérard, Fall 1882, quoted in Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters, 127.

[45] Jacques-Emile Blanche, Dieppe (Paris: Emile-Paul frères, 1927), 63.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Pierre-Louis Mathieu, Gustave Moreau: With a Catalogue of the Finished Paintings, Watercolors and Drawings (Boston: Little, Brown, 1976), 144. As early as 1856, Jewish patrons like Benoit Fould, the brother of Achille Fould, commissioned works from Moreau.

[48] Albert Cahen d’Anvers was a friend of Moreau’s, having bought The Young Man and Death from Durand-Ruel in 1873. Charles Ephrussi owned Moreau’s Jason and Galatea, which bore the inscription, “To my dear friend, Charles Ephrussi.”

[49] Vollard, Van Doren, and Weaver, Renoir: An Intimate Record, 93.

[50] In 1879 Charles Ephrussi was conducting research on a series of drawings by Raphael in association with an exhibition of Old Master drawings that he was organizing at the École des Beaux-Arts. Charles Ephrussi and Gustave Dreyfus, Catalogue descriptif des dessins de maîtres anciens exposés à l’Ecole des beaux-arts (Paris: G. Chamerot, 1879). In “Renoir’s Trip to Italy,” Ehrlich White writes extensively about Renoir’s interest in the work of Raphael.

[51] Renoir to Durand-Ruel, November 21, 1881, quoted in Herbert, Nature’s Workshop, 66.

[52] Charles Ephrussi, Albert Dürer et ses desssins (Paris: A. Quantin, 1882).

[53] John House, “Renoir’s ‘Baigneuses’” 581.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Ibid.

[56] Lionello Venturi, Les Archives de l’Impressionnisme (Paris: Durand-Ruel, 1939), 1:131–32.

[57] Bilski, Braun, and Botstein, Jewish Women and their Salons; Reuveni and Roemer, Jewish Consumer Culture; and Linda Nochlin and Tamar Garb, eds., The Jew in the Text: Modernity and the Construction of Identity (London: Thames and Hudson, 1995).

[58] Jean Cordey, “Chateau de Champs-sur-Marne,” Annuaire de la curiosité et des beaux- arts (1932), 22.

[59] Michel Steve, Béatrice Ephrussi de Rothschild (Nice: Andacia Editions, 2008), 69.

[60] Cordey, “Château de Champs-sur-Marne,” 22.

[61] House, “Renoir’s ‘Baigneuses,’” 578.

[62] Blanche, La Pêche aux souvenirs, 178.

[63] De Givry, “Charles Ephrussi,” in Dictionnaire critique des historiens de l’art

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ehrlich White, Renoir: His Life, Art, and Letters, 174.

[66] Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time, trans. C. K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin (London: Chatto and Windus, 1992), 3:577–78.

[67] House, “Renoir’s ‘Baigneuses,” 582.