The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The Art of the Americas Wing, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Opened November 20, 2010

Foster + Partners, London, design architects

A New World Imagined: Art of the Americas.

With contributions by Elliot Bostwick Davis, Dennis Carr, Nonie Gadsden, Cody Hartley, Erica E. Hirshler, Heather Hole, Kelly H. L'Ecuyer, Karen E. Quinn, Dorie Reents-Budet, and Gerald W.R. Ward.

Boston: MFA Publications, 2010.

359 pp; 257 color illustrations; suggested reading; index.

$60 (cloth)

ISBN 97808784676000

During the second half of the twentieth century three artists were regarded as the heroes of nineteenth-century American art: Winslow Homer, Albert Pinkham Ryder and Thomas Eakins. They were anointed with this distinction by the Museum of Modern Art with an exhibition organized by its director, Alfred Barr, shortly after the museum's founding. Employing a thesis developed by the social critic Lewis Mumford in The Brown Decades, which condemned the excesses of the Gilded Age, the museum sought to establish the modernist roots of an American tradition and ceded primacy to those artists whom they regarded as proto-modern; their work free of European influence, and their personae typifying the lonely genius (even the perennially popular Homer was cast in this mold) working against the grain of genteel taste and Victorian sentimentality.[1]

This is not the story told by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in its new Art of the Americas' wing. Instead, it presents an alternate reading that is most fully articulated in the wing's central core—the second level (third floor)—where the art of John Singer Sargent becomes the defining artist for nineteenth-century Boston. The recent efforts to resuscitate Sargent's career are huge and include Richard Ormond's multi-volume survey of the artist's career as well as several landmark exhibitions.[2] The focus on Sargent signals a thesis—that is only now beginning to gain traction—that the American fine arts tradition is based almost exclusively on European precedents. However, this is only part of the story visually enacted in the new wing. Another part of the story told by the Art of the Americas wing is how the influence of European and other traditions were manifested hemispherically. The first endeavor is wonderfully successful; the second less so.

It was a snowy morning in Boston when my husband, two friends and I set out for the Museum of Fine Arts to see the new Art of the Americas wing. Designed by the London-based firm Foster + Partners, the addition houses the museum's unparalleled collection of American art that has been amplified by objects from Central and South America. On the exterior, the new wing runs along the north and east sides of the building, closer to downtown Boston and the Fenway. Some critics remarked that the new walls look blank and seem at odds with the old building. I disagree; the color of the stone and the rhythmic and symmetrical divisions of the new walls echo the classical dignity of the old parts of the museum, and the melding looks just fine (fig. 1).

All told, there are fifty-three galleries, more than most museums have collectively, so this is a huge commitment to American Art, but then again the MFA has a large and important collection to showcase. Art is displayed on four levels and organized chronologically, the earliest art being on the ground level; art of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries is on the second level; nineteenth century paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts are on the third; art of the twentieth century through the mid–1980s is on level three. The floor plans are the same with the exception of the middle two floors that have extensions or pavilions to the east and west, which house special rotating collections, and what are termed "Behind the Scenes Galleries" that give visitors glimpses into curatorial and conservation practices. The principal galleries on all the floors have the same layout—a strong central spine, which features the level's major ideas with flanking, subsidiary galleries (fig. 2). One can enter the new wing from any level and from unrelated galleries, which can be disorienting. I found it best to enter from the courtyard, which is officially called the Shapiro Family Courtyard, a splendid light-filled, glass-enclosed space that soars upwards for four storeys (fig. 3). This large public room with a popular new restaurant manages to be both large and intimate and is an impressive threshold to the new wing.

The MFA is not the first major museum to challenge itself to rethink the installation of its holdings of American art to create a more universal view. Others, like the Brooklyn Museum, have done so as well, the imperative being that American art is less a product of stylistic evolution than a reflection of its geographic, economic and political status within the North American hemisphere. The current view, one that is echoed in today's textbooks, is that American art needs to be valued in relationship to indigenous populations, to its historic rapport with European culture, and within its tradition of inclusiveness. The MFA's avowed hemispheric commitment, however, is echoed more strongly in the accompanying book, A New World Imagined: Art of the Americas than in the galleries.

The exception is the ground floor galleries where the curators have made the strongest attempt to couple New England with Central American and Native American art with the Mesoamerican objects from Mayan, Aztec, Andean, and Native North American cultures in four contiguous galleries that form the central spine of the exhibition area (fig. 4). Gleaming glass cases hold large-scale 1000-year old Mayan burial urns from Guatemala, Olmec jades, Pre-Columbian gold and ceramics, and Navajo textiles from the American southwest. Flanking these splendid displays are galleries of European colonial objects that illuminate New England Puritan beginnings. On one side are two period rooms, both found in Massachusetts and both from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century. The first, the Brown-Pearl House, has a low ceiling and a darkened interior defined by heavy oak rafters and pine wall paneling with furnishings not original to the house, but contemporary and made by local craftsmen. The other, a timber frame room from the Manning House in Ipswich is a showcase for the decorative arts of the period that includes examples of early silversmithing

The central placement of indigenous art with subsidiary seventeenth-century Euro-American art is startling and an association seldom made in encyclopedic institutions, such as the MFA, which traditionally confine objects to their appropriate cultural or national category. The import of these introductory galleries is that the museum has chosen to contextualize early colonial art within a more continental view, subtlety revealing that the first European settlements were peripheral to the exuberant art of the southwest, northwest, Central and South America that surpassed it in sophistication, material beauty, and craftsmanship. It is a bracing view that can be acknowledged while still valuing the familiar, homey craftsmanship of our white forbearers that for over a century (certainly since the 1876 Centennial when the nation's colonial past was rediscovered) has spelled New England, if not American, beginnings.[3] Yet the text panels which relay welcome historical information about ancient cultures and early colonial art do not explain why these seemingly disparate cultural expressions are shown in adjoining galleries. For a fuller explanation one must consult the book that accompanies the Wing's opening

The story of New England beginnings is continued on the other side of the central galleries in a rotating exhibition space currently devoted to the art of colonial textiles. There are a total of four such galleries within the entire wing that house changing displays of material, such as textiles, drawings and photographs that are light sensitive. The current display is of embroidered samplers. And it is a treat. I took a moment to view the entire room and saw that the installation also included two portraits of upper class women who were themselves embroiderers, and I began to make some connections—this art by women of the period, and of all classes, served didactic purposes. It taught literacy—young girls learned to form their letters and learned their numbers as they embroidered their samplers. They also gained an understanding of biblical stories, which they illustrated with cross-stitch. Evidently—according to my friend the social anthropologist Bob LeVine who, with his wife Sarah, accompanied us through the galleries—Puritan New England had one of the highest levels of literacy in the world.[4]

There were other galleries of distinction including one on shipbuilding (fig. 5) and another devoted to the influence of the English-born painter, John Smibert, on colonial portraiture in Boston and beyond. While I thoroughly enjoyed these galleries and their in-depth representation of New England life in the eighteenth century, there was a disconnect between these enduring colonial artifacts and the central displays of native cultures. Frowning, my friends and I went up the stairs to the next level.

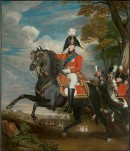

Once there, we entered a narrow hallway with stone and glass walls that serves as an entry vestibule for main galleries of colonial American art. Here we were confronted not by John Singleton Copley's iconic portrait of Paul Revere, but by his twelve-foot high equestrian portrait of the Prince of Wales done in 1809 (fig. 6). Sometimes a painting is placed in a hallway because it is either too big for the main galleries or not important enough. I do not think that either rationale are at work here, rather the placement of this monarchical portrait is deliberate—the commanding presence of the Copley's life-size portrait of England's future monarch challenges viewers' expectations. This is not Boston's beloved painter of colonial rebels, but an aristocratic Copley who, in order to improve his technique and patronage, moved to London before the Revolution. There he enjoyed success almost on a par with his fellow expatriate, Benjamin West. It also signals an uncomfortable truth that America was dependent on European models, a truism that is trumpeted throughout the first and second levels of the Art of Americas wing.

Once inside the first level galleries we are introduced to Revolutionary Boston where we now find the beloved and familiar portrait of Paul Revere placed in close proximity to his famous Sons of Liberty Bowl (fig. 7). There are also portraits of Samuel Adams and John Hancock similarly complemented by eighteenth-century New England silver and furniture of great elegance and finesse, and very much British-inspired. The MFA has large holdings of Copley paintings, and more of them, including the artist's well known Watson and the Shark,which he undertook for an English patron, are displayed in a gallery to the immediate right (fig. 8).

Beyond the central entrance gallery is an area titled "Arts of a New Nation." Fittingly enough, it is dominated by the English-born and English-trained Thomas Sully's The Passage of the Delaware, in which George Washington, commander of the Continental Army, is poised on horseback surveying the ice-clogged river from a high vantage point on the New Jersey shore (fig. 9). This historic incident was taken up again more famously by Emanuel Leutze in his 1859 Washington Crossing the Delaware (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) which, with its cinematic detail and theatrical composition, reflects the impress of his training in Düsseldorf. In Sully's version though, one is reminded of contemporary, large scale equestrian portraits of Napoleon and a comparison between the two leaders was popular at the time—Washington eschewing the crown which Napoleon accepted. Europe is never far from the American imagination.

There are a number of smaller, flanking galleries that hold an array of objects—chairs, chests, silver and textiles, as well as several period rooms—the Jaffrey Parlor (ca. 1730) from Portsmouth, New Hampshire; the Shepard Parlor (1803), Bath, Maine; and several interiors for the Oak Hill House (ca.1800), Peabody, Massachusetts. Tucked between a gallery of New England decorative arts and paintings done by expatriate painters is a small gallery devoted to Latin American art. Here there are textiles, furniture, silver, painted tin objects, and a large mid-eighteenth-century, six-foot high portrait of Don Manuel Jose Rubio y Salinas, Archbishop of Mexico by the mestizo artist Miguel Cabrera who was the archbishop's official artist (fig. 10).

Upon leaving this gallery of objects devoted to Latin America, one enters a room devoted to paintings and sculpture done by American-born artists working abroad. This juxtaposition furthers the story of the international provenance of American art and returns us to the idea embedded in the placement of Copley's Prince of Wales. Here are large-scale paintings by the granddaddy of American art, the American-born, British-trained Benjamin West (and I say granddaddy because he offered several generations of American artists their first exposure to the rules and aesthetics of grand manner painting) and another English portrait by Copley. There is also neoclassic sculpture by two sculptors, who like their fellow painters, needed to seek training abroad: Thomas Crawford's Hebe and Ganymede (ca. 1851) and Horatio Greenough's marble portrait of his dog Arno, named for the river in Florence where he lived and worked.

This is not to suggest that these 'ideas' are overtly displayed, but by organizing its rich cache of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century material in this manner, the MFA challenges visitors to reconcile the popular picture of American art as a self-made visual culture, with Copley as exemplary, with the reality of the professional and material needs of our early artists, which meant they needed to travel and study abroad. For many decades historians of American art have acknowledged the importance of European training for American artists, particularly in France.[5] However, the field has been slow to assess the implications of that fact; one celebrated in the new MFA wing.

Moving up to the next level, we again journeyed via the Shapiro Courtyard and once more were greeted by a surprising overture—three mural studies by the Boston painter, William Morris Hunt (fig. 11). The sketches are particular favorites since Hunt's Albany murals (1879) were the focus of my dissertation of many years past. What a treat to see them, along with sculptures by his friend, William Rimmer, as the introduction to the second level galleries of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century art (fig. 12). Now I know that the Hunt sketches were not put there for my benefit, so why are they there, what theme do they suggest that might be carried forward into the galleries beyond? There are at least two: that mural painting plays a larger role in American art than is generally acknowledged, and with its reference to European mythology and classical allegory, the importance of foreign influences in the establishment of national visual culture is further emphasized.

Once inside the second level galleries these two ideas become paramount. To everyone's delight, one is immediately greeted by John Singer Sargent's admirable painting, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit that, like the Copley's portrait of Paul Revere, is flanked by decorative objects, in this case two six-foot high arita ware vases that are reproduced in the painting (fig. 13). In this work of a darkened Parisian interior (it could also be the parlor of an elegant Back Bay apartment) four young sisters are shown in a variety of informal poses. The youngest is seated on the floor, while her three sisters stand in different parts of the room as if they had just been interrupted. The back half of the room opens up into a shadowy vestibule. At the left is one of the tall vases against which one of the daughters leans as she looks toward her sister. A fourth girl stands at the left at the apex of the zigzag that runs from the youngest child to the two in the hallway. With its irregular composition, the painting has been compared to paintings by Edgar Degas, and with its dramatic play of light and shade and rich, dark palette, along with the inquiring gazes of the children, it is often linked to Diego Velásquez's Las Meninas. Sargent was a great admirer of the French Impressionist and the Spanish Baroque master, which once again underscores Americans' reliance on the European past.[6]

There is every reason why Sargent's painting of the Boit children should have pride of place. It is a beautiful and compelling work and a favorite with the public, but the entire center gallery is devoted to Sargent and I wondered why. Then I remembered that above the Museum's central staircase is an elaborate and beautiful late mural painting by the expatriate Sargent. I had seen the mural on an earlier visit after it had been restored in 1999 (fig. 14). When the Museum restored its main, Huntington Avenue entrance, it also refurbished the grand staircase, cleaned the murals, and relit the space. Tall, robust vases originating in Asia have been placed along the staircase, and warm pink taupe walls complement the exuberant classicism of Sargent's many-paneled program. Borders and moldings set off the various mural sections that culminate at the top of the stairs in a series of tetrahedron shaped panels that fan out from a central core. The floating, mostly nude, male figures are both modern and archaic, uprooted from the pedestals and pediments where such figures are normally found are allowed to float free. Wishing to make a further claim on the importance of their Sargent murals, the Museum installed a series of studies organized in a circular gallery beneath the rotunda that further our understanding of the mural program, and of the diversity of Sargent's art. Nor are these the only Sargent murals in Boston. Earlier he created an elaborate and controversial series called The Triumph of Religion for the fourth floor hallway of the Boston Public Library, and was later commissioned by Harvard University to paint two fourteen-foot panels commemorating World War I, Death and Victory and Entering the War for the main stairwell of Widener Library.[7] As a muralist, Sargent becomes a Boston painter.

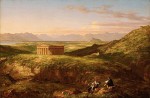

It now made sense why the curators installed the Hunt mural studies as prelude to the Sargent galleries. The mural paintings by Hunt in Albany, New York, and Sargent in Boston are public manifestations of the public culture of America embracing European precedent. This idea of a European model for American art is further augmented in the large gallery directly beyond the Sargents in a space called The Salon. I thought that this is probably what the MFA looked like in the 1890s with paintings by their favorite sons—William Morris Hunt most prominently, but also Washington Allston, and the sculptors, William Wetmore Story and Horatio Greenough (fig. 15). Paintings are installed salon style, one above the other, with scenes painted in Italy and France. Here are the expected Barbizon-inspired paintings by Hunt, less familiar is a view of the Italian campagna by that quintessential American landscape painter, Thomas Cole (fig. 16). This reminder that Cole spent several years in Europe led me to realize that the MFA is not trying to recreate the now familiar modern story of American art with its heroes—Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins and Albert Ryder. Two of them—Homer and Eakins--are off in a side gallery where the Boston-born Homer with his Fog Warning has pride of place (fig. 17). And where is Ryder? With the MFA's installing Sargent and works by Americans working in Europe in the innermost galleries, the centrality of the big three—Homer, Eakins and Ryder—has been atomized. But what does it mean to put Sargent in the middle? Suddenly Sargent's portraits resonate with Copley's portrait of the Prince of Wales, a direct link to Sargent's aristocratic portraits a century later; maybe not the Boit daughters, but certainly his larger-than-life-size portrait of Lord Londonderry done in 1904 (fig. 18).

As Homer, Ryder and Eakins have been regarded as the defining artists of the late nineteenth century, so too has landscape been the primary trope of antebellum painting; an idea which can be better sustained at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York with its large holdings of Hudson River School paintings. (Which brings up an interesting question: when does the regional become the national?) At the MFA, nineteenth-century landscape painting is termed picturesque and included in a section dealing with the Gothic Revival. Such an idea has been thoughtfully articulated by Sarah Burns in her landmark study Painting the Dark Side: Art and the Gothic Imagination in Nineteenth-Century America, in which she finds "doom and gloom" in Thomas Cole's celebrated landscapes.[8] This gallery opens up into several more devoted to the post-Civil War period and the Aesthetic Movement—it is a hodgepodge which is not meant to be pejorative, for this period is marked by eclecticism; to walk into a gallery and be surrounded by an array of styles and cultures, carved bric-a-brac and metalwork, stained glass and Tiffany vases, is to be plunged into the very heart of upper middle class American taste of the 1880s.

There is a lot of myth-busting going on in these galleries. Not only is the preeminence of Homer, Ryder and Eakins, and the Hudson River School challenged, but its later counterpart, luminism, an artificial construct of modernist art historians, is sidelined as well. It is not as if the MFA does not have excellent holdings by these celebrated artists. A great number were given to them sixty years ago by Martha Codman and Maxim Karolik. Works by Fitz Henry Lane, such as his Boston Harbor at Sunset, and Martin Johnson Heade's Approaching Storm: Beach near Newport with their low horizon lines, crystalline surfaces and epic stillness are fabulous examples of mid-century landscape painting (fig. 19). Yet, at the MFA they belong to the Boston landscape story and are paradigmatic of the enduring legacy of the Karoliks, so that these paintings also narrate the story of Boston collecting.

And it is a Boston story that this new wing enshrines, a tale that has an international provenance of settlement and trade, democracy and prosperity, of hubris and ambition. In other words, it is less about Art of the Americas (a good example of hubris) than about how Boston has viewed the world from the time the first Puritan set foot on Plymouth Rock. In the beginning, and maybe through the early years of the nineteenth century, this was also the American story. Perhaps in an attempt to move away from the New England story of American history and culture, the Museum adopted a hemispheric outlook, but it does so with objects bought and collected by Bostonians. However, to better understand the premises of the new wing, I consulted A New World Imagined: Art of the Americas, a book written by the curators in conjunction with the opening of the American art galleries. The book includes many illustrations of paintings and objects along with essays that shed light on their expanded view of American art. Elliot Bostwick Davis, chair of the Art of the Americas department, states, "This book is both a window onto this blending of traditions and an attempt to explore some of the perspectives that have contributed to the concept of American art" (14). At the same time, she is quick to point out that it was the MFA's collections that ". . . shaped how we [the Museum's curators] perceive the history of American art" (14). For them, the new wing offered an opportunity to "…reevaluate many previously held assumptions about how American art has been created, collected and displayed" (14); ambitious goals for an ambitious, $345 million dollar project.

Their mission, according to the Museum's director, Malcolm Rogers, was to place the art of the Americas in "the midst of their global collections" (7). This idea helps undergird the larger premise, but also reminds us that the global art accumulated by American museums was assembled by citizens for viewing in the United States. It is striking when viewing the floor plan of the MFA how much of its footprint is given over to the arts of the Ancient World, Asia, Oceania, Africa, and Europe. The assumption of the curators of the Art of Americas wing is that there cannot be a national art in the tradition established in the nineteenth century, such as the English school, the French school, the Dutch school, or the Italian school: "Rather than considering the art of the Americas on its own terms…as separate and distinct from the rest of the world, we…examined the way in which American art has been shaped by its encounters with cultures found around the globe" (16).

The book's introductory sections are followed by three essays that explore "Native Peoples of the Americas." The bulk of the book, however, is devoted to the European influences, a story which is complicated. One of the essays focuses on the classical tradition and its centrality in the formation of the arts of the United States including architecture. It is an interesting notion that the classical tradition was the basis of American art and culture. For the MFA, neo-classicism is the pivot around which indigenous art and global influences circulate and adhere. Put another way, in the MFA's view, neo-classicism of the eighteenth century—the era of the Enlightenment that was critical to the philosophical underpinnings of the American Revolution—provided the structure and the inspiration for the American art that followed. This influence is undeniable and apparent in early national architecture (often referred to as Federal) and sculpture. In terms of painting, it was the Renaissance tradition of perspectival drawing and the integration of volumetric figures within a three-dimensional space box that formed the basis of the early study of painting from Benjamin West forward. This too has its basis in the classical tradition.

The other essays that follow detail a quirky history of art of the Americas based on the many influences that impacted primarily the arts of the eastern United States. For instance, discussions of colonial art take place within the book section called "English." The careers of John Trumbull, Eakins and Homer are included in a segment devoted to French influence. But Trumbull's career could be equally well understood as coming under the sway of England, likewise Homer, and France for La Farge who in the book is included within Italy, as is, oddly enough, Copley. Within Spain are included Gilbert Stuart, John Singer Sargent, and Georgia O'Keeffe These are distinctions without meaning—who is the audience for this book? And very confusing distinctions even for art historians.

After reading the book and reviewing my notes, I went back to the Museum and this time started on the third level or fourth floor which I had missed earlier and which houses the Museum's collection of twentieth century art. With its high ceilings and white walls, there is an expansive feel to the floor, even though its footprint is smaller, that comes as relief after the clutter of the nineteenth-century galleries (fig. 20). In the central gallery there are fine examples of Alexander Calder mobiles, two smallish Jackson Pollocks, a fabulous Mark Rothko, and a smashing Frank Stella from his Hiraqla series (1968) that has never looked better. Off to the side is a gallery filled with first rate, early American modernist paintings from the Lane collection that fully complement and compliment the post-World War II art in the center. Beyond the Lane paintings' installation is a gallery of modernist photography with works by Alfred Stieglitz (specifically some hauntingly beautiful close-ups of the nude body of Georgia O'Keeffe), and Paul Strand, perfect counterpoints to the preceding gallery. Beyond galleries of dishware and necklaces is a gallery titled "Twentieth Century People." Here are figure paintings by veterans of the Ash Can school, George Bellows and later realists, such as Alice Neel, Andrew Wyeth, Larry Rivers and Normal Rockwell. Leaving this gallery, you come back to the central abstract gallery, only to discover that the figure is still there in a noble, red painted steel columnar work by David Smith called Sentinel III (1957), an early painting by Pollock called the Troubled Queen, and a display case that I had missed earlier containing elegant jewelry including a stunning silver necklace designed by Calder for his sister—the necklace evoking a human presence. The floor was empty except for students sketching nearby in the early morning hours. I hated to leave, and it dawned on me that the curators had accomplished something remarkable. The nineteenth-century level felt cluttered and claustrophobic, effectively recreating what we would experience if we could be magically returned to the museum of the 1890s. So I went back to the second level intrigued and began to rethink what I had seen previously with a new perspective.

This time I started in a small gallery off to the side that I had missed before. It held a temporary exhibition titled, Artists Abroad: London, Paris, Venice, and Rome, 1825–1950 and it was an important reminder that the 'problem' with nineteenth century American art is that it is provincial—we were not the center, we were the periphery—this is the nineteenth-century American story and it is told extremely well in Boston, better than anywhere else right now (still to come are the openings of the reopening of the Metropolitan's American Wing and the reinstallation of the very important American collection at Yale University Art Gallery, both scheduled for 2012).The notion that American art up until World War II is provincial (the exceptions being architecture, photography and film) is not one that is bruited about. There is also another problem encountered when discussing American art of the past, which is that we are the only major Western nation that promotes its 'provincial' art, caressing it, massaging it, trying to make it better and more important than it is. The good news is that without 'fessing up, this is the story that the MFA is telling: American art is provincial and the audience does not care—they love it! As do I! The crowds are enormous and comfortable in the spaces and undaunted by the maze-like layout as they thread their way from one section to another. The public doesn't seem to mind. They are there to see old friends from the past and to make new acquaintances. They read the text panels and explain them to one another and then look to see if what they read makes sense. They don't have that lost, overwhelmed look of tourists at the Museum of Modern Art; rather they are at home and enjoying themselves. I think even if one is from out of town, the 'Boston' story—the Pilgrims, Copley, the Freedom Trail—is so familiar now that outliers can engage the story as well, one that has become our own.

Simultaneously, the curators have expanded and complicated the 'story' for while it is to a certain extent self-congratulatory, it also continuously circles back to the truism of international cultural exchange. Europe—England, Italy and France—dominates. In the late nineteenth century, Japan was influential but hemispheric contact, with the exception of Martin Johnson Heade and his exotic paintings of Brazilian hummingbirds, was minimal (evidently the Museum owns no South American paintings by Frederic Church).

When I visited the Museum the first time I was distracted by the title of the wing "Art of the Americas," and experienced the two nineteenth-century 'levels' (in reality the third and fourth floors), as crowded and with a non-existent viewing path. The second time was more rewarding and reminded me that good installations, even more than temporary exhibitions, deserve frequent viewing. More to the point, if one 'got it' right away, what would be the point of going back. I also came to two conclusions: one is that museums have always grouped art geographically. For instance galleries devoted to Asian Art will have Chinese, Korean, Japanese and sometimes Indian objects, maybe not in one room, but in separate spaces side by side. There may be attempts to trace trade routes from one Asian culture to the next in order to map the spread of influence, say, in the representation of the Buddha, but for now it is too much of a leap to transcend profound differences in cultural production between the United States and Latin America. Instead, what is being told is a Boston story whose subtlety unfolds within the context of the Art of the Americas.

The other conclusion I came to, and one that is not fully articulated by either the book or the new wing, is that we have moved into an era—which may be called post-modern but even that's not a satisfactory label—in which objects in a gallery can be visually satisfying, but at the same time need to be contextualized. In this new wing, and I think it is a lesson to be learned by all museums with in-depth collections of American art, connoisseurship needs to be on equal footing with storytelling. Fifty years ago when there was a prevailing sense of connoisseurship, an order was determined by a curator's informed aesthetic judgment. Today it is difficult to find such installations—ones that are best defined by a 'clean, white-box' mentality. Museums today are beginning to reach far beyond an aesthetically informed public to better explain the visual culture of a given community. Or to put it another way, to explain why a given work of art deserves wall space—what is its cultural value? I believe that this is the dirty, little secret of curatorial challenges these days, how best to tell an object's back story? And how much 'back story' is needed, and what 'back story' is to be told? Where does it fit in the artist's career; how has it been appraised by critics and historians over the years; what does it say about a given moment in time, what is its relevance today, and how did it get to the museum? Maybe it was easier when the work just had to look good. Regardless, there has to be an informed curatorial view of what to include, where it should be placed, how it relates to the works around it, and what might an audience take away from seeing this object under these circumstances; and will they come back?

I have left out a great deal. There are galleries devoted to folk art and trompe l'oeil painting, to musical instruments, to drawings and decorative arts, and there are more period rooms. Nor have I touched on the large commitment the Museum has made to its interactive galleries, which may become the gold standard for other such innovative enterprises.

What engaged me the most, aside from seeing some wonderful old friends, was sensing a new beginning for scholarship in American art; one that focuses less on exceptionalism or modernist concerns and connoisseurship, but instead embraces American provincialism. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the American experiment in participatory democracy needed new styles for its public architecture, sculpture and painting that did not smack of the aristocracy or the church—the world was to be made anew. At the same time American artists could not, or did not want, to reinvent the wheel; the rules of architectural and pictorial representation—the classical orders, illusionistic drawing, the primacy of the figure, and the sensuality of pigment—continued to hold sway. The rules they knew and admired were European, the thought being that artists in a young nation would improve on the academic model and that the country, free from the decadence and tyranny of the old world, would witness a "new dispensation", that the classical tradition would be reborn. In the beginning the artists who are credited with establishing our fine arts tradition—West, Copley, Charles Willson Peale, Trumbull, Gilbert Stuart, Washington Allston, and John Vanderlyn—all sought European training. It was the reception that this learned, cosmopolitan generation received once back in the United States that discouraged them and hampered their progress. It could be argued that they lacked the skill of their European contemporaries, but I think instead their lack of success speaks to the provincial reality faced by these artists trained abroad. There were no museums, no ancient ruins, no art schools, no community of artists or art connoisseurs that form the petri dish of artistic inspiration. There was no context for European art and culture. At the same time, there was no other gauge by which to evaluate creative genius. This did not discourage later generations of artists, which, up until the 'triumph' of American art after World War II, continued to travel seeking training, models and inspiration for their art. The unavoidable truth, which is demonstrated forcefully and with great élan in the Art of the Americas wing, is that the American fine arts and decorative arts traditions are inescapably reliant on the rules and precedents of Western European art.

Sally Webster

Professor Emerita

salweb[at]nyc.rr.com

[1] See Lewis Mumford, The Brown Decades, A Study of the Arts in America, 1869–1895 (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1931) and the exhibition catalogue, Homer, Ryder and Eakins (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1930).

[2] The first volumes of Richard Ormond's catalogue raisonne appeared in 1999; the latest was published in 2010.

[3] The primacy of the New England narrative as the Ur text for all of American art is challenged by Roger Stein and William Truettner in Picturing New England: Image and Memory (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999).

[4] See Kenneth Lockridge, Literacy in Colonial New England: An Enquiry into the Social Context of Literacy in the Early ModernWest (New York: W. W. Norton, 1974).

[5] Lois Marie Fink, American Art at the Nineteenth-Century Paris Salons (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990); H. Barbara Weinberg, The Lure of ParisNineteenth-Century American Painters and their French Teachers (New York: Abbeville, 1991); Kathleen A. Foster, Thomas Eakins Rediscovered (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997); Americans in Paris 1860–1900 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006); and Elizabeth Kennedy and Olivier Meslay, American Artists & the Louvre (Chicago: Terra Foundation for American Art, 2006).

[6] An important study of this painting is Erica Hirshler. Sargent's Daughters The Biography of a Painting (Boston: MFA Publications, 2009). Dr. Hirshler is also Croll Senior Curator of Paintings, Art of the Americas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[7] For a thorough and insightful study of Sargent's elaborate mural program for the Boston Public Library, see Sally M. Promey, Painting Religion in Public: John Singer Sargent's Triumph of Religion at the Boston Public Library (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999). The Harvard panels were completed in 1922.

[8] American culture and the medieval revival are the subjects of Sarah Burns' ground-breaking book, Painting the Dark Side: Art and the Gothic Imagination in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004). The phrase "doom and gloom" is the title of her first chapter, 1.