The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures: American Masterworks from Minnesota Collections

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts

February 22 – May 3, 2009

The history of art in the United States is a history of private patronage. Whether motivated by a sense of national, regional, or civic pride—or more simply by the desire for something affordable for the over-mantle—the benefactors of art in America have always been its primary source of support. Even after the emergence of a national academy and salon system, individual patrons still remained visible as the country's cultural string-pullers. Think of the Century Club in antebellum New York; a fraternal order that brought artists in chummy contact with art collectors, making connections no less important than the one between painter Eastman Johnson and William Blodgett, a bigwig at the Met. Think of Isabella Stewart Gardner; the Boston socialite who so desired a portrait of herself in the style of John Singer Sargent's Madame X, that she asked her friend William Merritt Chase to throw a party for Sargent at his Tenth Street Studio quarters—with décor and dancers ripped straight from El Jaleo. Think of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney at the Whitney, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller at the Museum of Modern Art, or Peggy Guggenheim at the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, women of means all of them, and patrons who funneled their private love of collecting into public institutions. Think of Edith Scull requesting thirty-six full-color versions of herself from Andy Warhol. But we need not go to such lengths to demonstrate the fundamental importance of patrons in the United States. As any student of the American art survey can easily tell you, without John and Elizabeth Freake, there would be no Freake limner.

Patronage doesn't stop when the paint is dried, however. As the recent exhibition, Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures: American Masterworks from Minnesota Collections attests, the health of American art has depended just as vitally on the continuing stewardship of private collectors. These are the patrons who will never have a chance to meet Warhol or Sargent or Johnson, but who tend to their works as lovingly as any adoptive parent.

Staged at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (MIA) from February 22 to May 3, 2009, Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures made this point with a respectfully light hand (fig. 1). While all of the show's more than 150 works were drawn from thirty-one local private collections, associate curator of paintings and modern sculpture Sue Canterbury organized the exhibit according to a fairly conservative canonical order. The exhibit covers over 100 years of painting in the United States from the itinerant portrait painters of the early nineteenth century to the early modernist works of the Ashcan School and the Stieglitz Circle.[1] This straightforward approach permits both the curator and the collectors to recede into the background, allowing the artworks themselves to take center stage. It's a nicely deferent posture, and one fully in keeping with the parental analogy that seems to have guided Canterbury's approach.

While the pride of the collector is all on the side of the artwork itself—one was reported to have said that the MIA show was like having a child in the school play—Canterbury sees fit to give credit where credit's due. The collectors represented in the show have all been faithful in their care of the pieces. These are people, Canterbury reminds us, who have to monitor the temperature and humidity of their living rooms, just to do right by their Winslow Homer (fig. 2). And what a Homer it is! Summer Night – Dancing by Moonlight, 1890 is a stunningly characteristic piece: an exquisite seaside nocturne with swelling breasts and surging tides in lyrical lockstep. These are people who become scholars in service to their works. Collectors might begin a love affair with James Abbot McNeil Whistler on the basis of pure physical attraction, but they deepen this passion through study: attending lectures, reading biographies, and following up on the details of family trees. Whistler's The Widow of around 1887 rewards just this kind of snooping. A strikingly un-insightful portrait of the woman he'd later marry, Whistler has applied skein upon skein of brown paint to the wife of the recently deceased architect, E.W. Goodwin. Tellingly, there's more spark of personality in the potter's mark monogram he's placed at bottom right. Devotion of this kind exemplifies a selflessness that justifies Canterbury's final observation that while the collector might write the checks, it is in fact the "collector [who] is 'owned' by the works."[2]

The exhibition's first section (one of seven), "Folk Art" implicitly puns upon this quasi-metaphysical inversion of owner and owned. In this part of the show, we meet some of America's first art patrons, appearing indeed as captured by their artworks (fig. 3). We encounter the noble Captain Forrester of Marblehead, Massachusetts laid out in oil on board by Sheldon Peck in 1825, a fashionable Portrait of Catharina van Keuren painted in her empire dress by Ammi Phillips, also in 1825, and Richard John Cock forever young in his posthumous portrait of 1815 by Joshua Johnson (figs. 4 and 5). This gallery of pioneering art patrons resonates with the exhibition's theme, and partly as a result of this, it is the show's strongest section. Other important factors contribute too. Because this room is the smallest space in the exhibition and the first, visitors are especially fresh and attentive to these lesser-known artists. As a result, this gallery is most conducive to imagining the experience of the collector, a process of discovery that is said to hinge more on gut instinct than on book learning or art market calculus. If we are charmed by the almond-shaped eyes and their overworked lashes, if we smile at the failed effort at foreshortening, if we're thrilled to see a portrait of Rebecca Warren next to an embroidered scene made by her very hand (fig. 3), then we find ourselves reliving the first blushes of attraction that must have motivated these works' current owners. We might even feel a twinge or two of jealousy, as I certainly did.

This envious sensation might even awaken our own "noble dream" of becoming art collectors. To this feeling, the wall text and catalog offer ready encouragement. These supporting texts seek to banish the "assumptions … that a collector must be rich, educated, and in possession of rarified knowledge." Instead, we're promised that nothing "could be further from the truth." On this point, the visitor may be justified in harboring some suspicions. There are a number of "good gets" in the room, canvases whose value lies more in the margins of art history textbooks and auction sheets than within the four edges of the canvas. Surely, the collectors of these trophies aren't as naïve as the artists who painted them.

An experienced museumgoer, for example, will know to congratulate Samuel D. and Patricia N. McCullough on the acquisition of their Joshua Johnson piece (fig. 5). Because of his status as the first professional African-American painter, Johnson's works can command high prices at auction; this in spite of the fact that Johnson's portraits are almost indistinguishable from the other limners—right down to the sitters' pink skin. For the purposes of his career in early nineteenth-century Baltimore, stylistic anonymity was requisite to Johnson's success. But this same quality has since made it hard to authenticate his works. The uniqueness of Johnson's artistic imprimatur as the "first black portraitist" and the limited and uncertain supply of his oeuvre has sent prices as well as forgeries skyward. The McCulloughs have done quite well with this purchase, indeed. The wall label tells us about Johnson's racial heritage, but does not explain the significance of this fact to the practice of collecting: a missed opportunity, if you ask me. This is not to say that dollar value should have been the most important issue in this exhibition, or even that price is all that noisome a value in the first place. The factors that determine cost and those that determine interest are usually not so disentangled, after all, as the especially fine work by Johnson makes clear. However, by keeping issues of price just barely concealed, the exhibit splits its viewership between those who know how to spot it and those who don't.

An exhibit like Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures, which is at least implicitly a show about collecting, might have seized more opportunities to consider the intersection of art history and the art market. This was not addressed with the Johnson, nor did it surface anywhere else in the show. But another, related avenue for exploration—provenance history—was dealt with more frequently. An early nineteenth-century portrait by John Usher Parsons, Mrs. William E. Goodnow (Harriet Paddleford), c. 1837, is a case in point (fig. 6). From the wall text, we learn about the conditions of the painting's original commission; its travels across the country from Maine to the Kansas Territory; and its rediscovery in the 1930s by the collector Nina Fletcher Little. This didactic panel should be awarded special points, too, for informing visitors that paintings by Parsons are scarce, and so are especially prized by collectors. A short narrative like this one takes the best advantage of the exhibit's conceit.

When an art museum admits to the object-like quality of its pieces—as Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures necessarily does in its presentation of artworks specifically as possessions—it invites us to imagine the different times and places these things once inhabited. The story of Mrs. William E. Goodnow satisfies this curiosity, and we pick up a thing or two about history and art history in the process. Mr. Goodnow was an abolitionist who left his wife behind in order to settle Kansas in the name of the cause; and Little was a tastemaker who helped spread the "folk art fever" of that period.[3]

One only wishes there were more such accounting for the artworks in Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures. Provenance chronicles, like all good biographies, can be real nail-biters, and a few more of them would have gone a long way toward spicing up the show. They're absent almost entirely throughout the long middle sections of the exhibition, and it's only near the very end that we pick up the thread once more, in the wall text for George Bellows's Upper Broadway from 1907 (fig. 7). Here we learn that the painting once hung in the home of Katherine Hepburn. All the excited gasps of recognition I heard as people came to this panel is proof enough that the audience is hungry for more such "biographical" details. And the Bellows, you ask? Well, frankly, it's not his best work. Invitation to vicarious experience was Bellows's particular genius, but here we feel the palette knife's motions a bit too keenly, enough to know Bellows wasn't quite confident in these scrapes and hatches.

Between John Usher Parsons and George Bellows, however, lie nearly one hundred years of American art history. For this, the majority of the exhibition, the collecting theme dies down in deference to the works themselves and their traditional place in the American art historical canon. There are still-lifes and genre scenes, the former by Severin Roesen, Robert Scott Duncanson, and William Harnett, and the latter by Eastman Johnson. There are geological surveys and ethnographic illustrations thanks to the prodigious efforts of Seth Eastman. And there are landscapes, lots and lots of them. We encounter wide-angle mountain tops, hazy summer pastures, moonlit nocturnes, low-slung strands of horizontal coastlines, and monochromatic squares of snow-covered woods. These come from no less formidable a group than the likes of George Inness, William Haseltine, Asher B. Durand, John Frederick Kensett, and the Minnesota local, Alexis Fournier. The last, befitting his hometown boy status, makes up an especially large section of the exhibit represented by seventeen works from at least eight collections.[4]

What's curious about Fournier's work is a quality that could be called typically Midwestern. His paintings sustain attention without courting it. Think of Garrison Keillor on the radio: the voice and its spoken details are deep enough to fall into, but it's often just as easy to tune out or move the dial. What happens within the four edges of Fournier's paintings is something similar. We see mill ruins, factories, bridges, and falls through a panning glance, and we are always on our way to or from these sites, never quite achieving the mastery of unmoving presentation. Rena Neumann Coen, Fournier's most dedicated scholar, has commented on this quality of the painter's compositional nonchalance. Accounting for the "lack of a central focus" in Fournier's work, Coen surmises that the painter may well "have intended to incorporate [the scenes] into a large scale panorama."[5] Such an ambition, if true, would very well account for his inventory-like work throughout the 1880s. Hung together in the galleries at the MIA, the pieces nearly achieve Fournier's goal, albeit on a smaller, less immersive scale. Our vision pans distractedly from one scene to the next, suturing them together into a continuous, richly drawn locality.

Fournier brings up one of the most conspicuous idiosyncrasies of private collecting. While national markets will often undermine the value of regional artists, private collectors tend to be eager for views of familiar scenes. Ditto goes for the local museum-going audience. In this regard, Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures satisfies its demographic richly. One such case in point is a small room dedicated almost entirely to Seth Eastman's watercolor studies, where the local angle widens to broader interest. Trained in drawing at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Eastman was first assigned to Minnesota in 1829 and returned to it later as a commissioned officer in 1841, when he was based at Fort Snelling, a formidable outpost at the conjunction of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. Part of the function of Fort Snelling was to support the U.S. Indian Policy on the northwest frontier. Accordingly, Eastman focused his illustrative attentions on the region's Ojibwe and Dakotah peoples.

These studies offer refreshing contrast to the works of Eastman's better-known contemporary, George Catlin whose staged portraits of Native Americans fulfilled the Western ideal of the "noble savage." In carefully drawn profiles and excessively rendered costumes, Catlin's works also meant to offer ethnographic details that documented what was presumed to be a "vanishing race." In comparison, Eastman's works offer many striking—and refreshing—differences. Frequently, these small works aren't really ethnography, but more properly genre scenes. One work, Indian Courting (n.d.), is better suited to comparisons with William Sidney Mount than Catlin. In Eastman's scenes, we get a feel for Objibwe and Dakotah customs, but the overriding mood is more sentimental than clinical. Likewise, pieces such as Gathering Wild Rice (n.d.) and Indian Sugar Camp (n.d.), offer easier analogies to the casual pastorals of Eastman Johnson, especially his Cranberry Harvest or Sugaring Off, a version of which hangs nearby in the MIA exhibit.

Indian Courting is the most direct of the Eastman works in its handling of the figures' bodies and faces. But even here, Eastman displays a thoroughgoing disinterest in figurative modeling. To this, we might assign various causes: lack of ability, the scale and nature of his medium, or a general preference for action over actor; but the effect is a collection of Native American scenes that retreat from the pseudoscience of physiognomy. Even in Moccasins (c. 1850), an inventory of shoe types that at first blush seems the most obviously ethnographic, Eastman's touch frustrates the epistemological urge, and invites a phenomenological one. We want to slip our feet into these shoes, with their soft leather tongues and their dark, folding insoles. These shoes are worn, but not yet relics.

Eastman appears in the "Early Minnesota" section and, in his hybrid oeuvre, leads into the show's next chapter, "A National Art: Landscape, Still Life and Genre." Here is where we find the Eastman Johnson scene of hale New Englanders, collecting sap for syrup. It's a tawny-hued, only partially modeled study, with waxworks where the people should be, but nonetheless the work holds considerable interest in historical detail. Painted in the midst of the Civil War, the oil pays tribute to the self-sufficiency provided by Yankee maple syrup, in contrast to the slave-dependent sweetener, cane sugar. This section of Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures also finds the viewer in front of Robert Scott Duncanson's Still Life with Fruit and Nuts (1848) and Severin Roesen's Fruit Still Life (c. 1860s) (figs. 8 and 9). The Duncanson is the better of the two, if your tastes run toward undraped tables and the pathos of shriveling grapes; but the Roesen is more optimistic, with its perfect spheres of dew, one on almost every swelling fruit, and the curling, grapevine signature.

However, the bulk of "A National Art" is devoted to landscape. In fact, while the exhibition catalog neatly lays out three sections between "A National Art" and the final chapter, "On the Cusp of Modernism, " the visitor to the exhibit is not likely to notice these at all. "The Transatlantics: Cosmopolitanism, Expatriates and American Impressionism," "Tonalism," and "Minnesota Painters" jumble together in the show's yawning middle section. Here, clarity and discovery are hampered by too many landscapes. Scale is the major hindrance. The intimacy kindled by the show's fine small works inflates to sofa-size canvases in the Barbizon and Tonalist styles. This is a different order of collecting, it seems, in which size matters, and more is more. The curators might have been wise to respectfully disagree.

As a consequence, it's easy to stroll by these scenes like so much, well, scenery. An impatient viewer might forget to stand squarely in front of these big pieces and surrender to its pleasures. My favorite painting for this was Homer Dodge Martin's White Mountains (Mts. Madison and Adams) from Mt. Randolph (c. 1862-63) (fig. 10). The snow on these two peaks extends across the canvas in a brilliant span, seeming only to hover above the mountains in a partially rendered form. In the bottom right foreground, scrappy evergreens feel like the tattered remains of an older mode of theatrical landscape. The artifice is crumbling, and what should be in the distance—sky and snow—crowds forward on the picture plane. Suddenly, we're reminded of the troubling conditions of 1863. What's revealed to us is not a stable space in which to soar, but more paint than we expect. The pasty icing of snow, like yellowing silver, is more shape than substance, pushing more aggressively into our visual space than the peaks that draw back underneath. The sky happens in horizontal strokes of grey and blue, which build on top of each other crosswise and at cross purposes. In White Mountains, the eruption of paint and design—each on their own terms—is a startling revelation, and preparation for the stunner of the final gallery, Marsden Hartley's An Evening Mountainscape (1909).

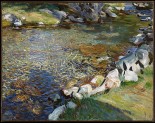

We're helped on our way toward Hartley, with the careful placement of a few exquisitely rendered stepping stones, courtesy of John Singer Sargent's The Moraine (1908) and his Val d'Acosta: Stepping Stones (c. 1907) (fig. 11). Piles of rocks appear in both, seen from a hiker's vantage point and occupying a majority of the canvas. For all the weight of stones, these are color-and-light studies, so much so that the rocks' dark grey shadows have often come unstuck from their sun-bright sides. This is taken to the point of some confusion in Val d'Acosta, where the viewer can be forgiven for mistaking the rocks along the shoreline for so many waddling penguins. The faceted stones cleave more closely in The Moraine, but it, too, is a startlingly abstract canvas. The rocky edges pile on top of one another in this treacherous path, and the visible distance offers no comfort. Ahead we see only bent arabesques of paint that might as easily describe a dragon's head or an open mouth, as a horizon obscured by clouds or snow. Seen from afar or through squinted eyes, the analogy here is not penguins, but Jackson Pollock. Like the hiker faced with The Moraine, we plunge onward down the rocky path toward modernism.

After Sargent, we encounter the likes of Ernest Lawson, William Glackens, and Maurice Prendergast, who serve here in their customary Janus role: swinging doors between nineteenth-century aestheticism and early twentieth-century formalism. Put in such close proximity to the Sargent paintings, though, the visitor is allowed to notice an illuminating through-line. These transitional painters push the logic of Sargent's jewel-cut terrains, offering urban views and fashionable figures in so many partitioned surfaces. Cases in point include Lawson's New Hope, Pennsylvania (n.d.), streaks of gloppy paint that recall the heavy, bubbling colors of stained glass; and Prendergast's The Bartol Church (The Fountain) (1900-01), where the artist appears less obsessive in his trademark cloisonné workmanship, but only barely.

Lawson, Glackens, and Prendergast were all members of The Eight, that group of quasi-secessionists who exhibited together at the Macbeth Galleries in 1908 to calamitous critical response. These three were tame when compared against George Luks and John Sloan, whose brasher canvases earned the group the derogatory "Ashcan School" nickname. One is allowed just this kind of comparison here, noting how different Luks's firelit Leena (William Glackens's Daughter) (1910) is from Prendergast's Japonesque fashion plate, Elegant Woman in Blue Dress (c. 1893-94). Moreover, Luks and Sloan have been joined with their younger confrere, George Bellows, a latecomer to the scene who missed the Macbeth show by mere months.

Sloan takes his turn in the exhibit with a middle name he's not usually accorded, as "John French Sloan." This addition takes on the feel of a sobriquet when used as a byline for works work like Gloucester (c. 1914). Here, Sloan appears to be trying his hand at Fauvism, applying the wavering lines Henri Matisse used for faces to the much more obliging subject of trees. Luks deserves pride of place among the Ashcanners for his Leena, whichgives both more and less than we expect. A theatrical young woman in full tilt, her gestures and bow tie splash across the canvas in high-keyed paint. And yet, Luks has also bestowed his friend's daughter with the subtle underworking of facial modeling. There's not much to her doughy face, but it emits its own light—a halo of projected confidence in coming adolescence. As with Luks's treatments of performers in private spaces, this canvas explores the tug between what is shown and what is held to oneself. This is the condition of the show itself, an exhibition that often holds back more in reserve than it outwardly presents.

In Canterbury's choice to end the show "on the cusp of modernism," she forces the final pieces to assume a prefatory posture. We search the Hartley, Sloan, and Bellows for hints of the modern hallmarks we know lie ahead: paint for paint's sake, expressive lines and colors, flattened surfaces, and all-over designs. Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures doesn't leave us where compendiums of American art might have in years past: at the threshold of international modernism where parochialism was supposed to have given way to a formalist family of man. Instead, the exhibit's galleries proceed in a loop, so that when the audience exits through the Folk Art gallery, they've come full circle. As a result, it appears that modernism is not just presaged, but also curiously fulfilled by all those flat-eyed figures.

The exhibit concludes with Hartley, Luks, Marsden Hartley, and a rare and stunning Edward Steichen, all poised just at the "the advent of modernism," as Canterbury explains. The closing gallery leaves visitors dangling on the historical edge, just before cubism pushed American painters toward outlined forms and flattened figures. Where Max Weber or Joseph Stella might be in a survey text, we find instead Joshua Johnson Phillips and John Usher Parsons, and the substitution seems fair enough. This is closed circuit American art history, in which the capacity for abstraction appears to have been a distinctly American trait all along. The most provocative hang of the whole show drives this point home: George Luks' Leena and Ammi Phillips' Portrait of Catharina van Keuren occupy either side of the same wall, both in view of Nina Fletcher Little's Mrs. William E. Goodnow—a revolving door monument to the all-American will to self-expression (fig. 12).

Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures stands firmly within the boosterish tradition of this country's tradition of art patronage. It's a proud show: proud of America's generations of plucky painters, and proud of the latter-day Minnesota collectors who remain their stewards. One worries that this pride will harden into flat-footed patriotism or, worse, obsequiousness. But it never does. Instead, the exhibit represents an admirable experiment in extending the MIA's encyclopedic mission, without breaking the bank. Temporary touring shows are expensive and they often don't accomplish half the work done by shows like Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures. By sweeping through the canon, even if a conservative version of it, this exhibit serves as a very useful supplement to the institution's comprehensive view of the world's art history.

We're in the midst of a small boom of collectors' exhibits, coinciding with the recent bust in major acquisitions and gifts. Increasingly, museums must turn to private collections as a resource for filling in institutional gaps. After a round of recent, high profile lay-offs, the Minneapolis institution is unlikely to remedy the holes in its American collection anytime soon. Looked at in this light, the conservative approach taken by both Canterbury and the collectors is not only justified, it's welcome. Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures does not push envelopes. It offers visitors a well-known story of painting in the United States, augmented only modestly with views from a local angle and dishy discoveries that prove what we already know. As such, it is a studiously responsible show, necessarily doing double duty as both an American survey and a temporary exhibit. Sue Canterbury is to be congratulated for striking this balance and the collectors, too, must be thanked for their care and generosity.

Jennifer Jane Marshall

Assistant Professor of North American Art

University of Minnesota

Marsh590[at]umn.edu

[1] A group of Faith, Hope, and Charity by Hiram Powers from 1866-71 is the only example of sculpture, and an anonymous, painted wooden box is the only piece of three-dimensional decorative art.

[2] Sue Canterbury, "Minnesota Collectors," Noble Dreams & Simple Pleasures: American Masterworks from Minnesota Collections, (Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2009), 8.

[3] For more on "folk art fever," see Virginia Tuttle Clayton, et al., Drawing on America's Past, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003),69.

[4] Fournier was born in St. Paul, Minnesota on July 4, 1865. Since many of the Fournier works were lent anonymously, it is difficult to tell from the catalog exactly how many unnamed lenders contributed to the Fournier section.

[5] Rena Neumann Coen, In the Mainstream: The Art of Alexis Jean Fournier (1865-1948), (St. Cloud, Minnesota: North Star Press, 1985), 8.