The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Catesby, Audubon, and the Discovery of a New World: Prints of the Flora and Fauna of America

Milwaukee Art Museum, Koss Gallery

December 18, 2008-March 22, 2009

A small, but richly layered exhibition of work by naturalists Mark Catesby, Alexander Wilson, and John James Audubon recently completed its run at the Milwaukee Art Museum. For this show, Associate Curator Mary Weaver Chapin used an opportunity to combine holdings from the museum's permanent collection with several new acquisitions to create a memorable display of eighteenth and nineteenth-century natural history prints. Consisting of approximately sixty assembled visual works interspersed with an impressive collection of related media (primarily maps, print volumes, and journals) secured from other regional collections, the Catesby, Audubon exhibit in Milwaukee explored interrelationships between science, technology, and art during a historically rich period that began with Englishman Mark Catesby's first visit to the British American colonies in 1712 and concluded with the final comprehensive publication of work by John James Audubon, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, originally issued in 1848.

While John James Audubon continues to be recognized as the most famous of these three naturalist-artists, in the last decade there has been something of a Catesby revival and exhibitions featuring wildlife artists in addition to John James Audubon are not unusual.[1] Nonetheless, the Milwaukee exhibit was remarkable for the intricate way that it contextualized the visual works produced by these three men. The show successfully examined not only the forms of intellectual curiosity that produced such work during more than a century of great social and environmental change, but also explored in detail how commercial print technologies and the economies of paper production influenced artistic representations of the natural world throughout this period.

Working cleverly with an eclectic mix of resources, the Catesby, Audubon exhibit developed three related lines of inquiry for its viewers. Weaver specifically designed the show to explore: (1) how visions of the "new world" shifted significantly between 1712 and 1848, (2) how the process of "scientific discovery" came to be intimately connected with artistic expression, and (3) how rapidly developing print and paper-making technologies shaped and defined efforts to document plant and animal life indigenous to the North American continent. Displayed in the Milwaukee Art Museum's intimate Koss Gallery, the choice to utilize this limited exhibit space for such a complex narrative may have been disastrous in any other instance, but the museum staff did a masterful job of calibrating its presentation. The overall effect was very powerful, if not enchanting.

Upon entering the Koss Gallery, visitors immediately encountered the exhibit's golden yellow walls, which enlivened Milwaukee's grey, winter landscape, and simultaneously provided a perfect backdrop for the intricate hand-colored prints assembled for this show (fig. 1). The museum's thoughtful inclusion of large, hand-held magnifying glasses for gallery visitors made the exhibit that much more welcoming and allowed viewers to engage with the works at an even more satisfying level.

Mark Catesby, 1683-1749

The exhibit began chronologically by focusing viewers' attention on the life and work of Mark Catesby. Born in Sudbury, England in 1683, Catesby initiated a seven-year tour of the American colonies in 1712, taking field notes and making sketches as a casual observer without ever intending to complete a very rigorous artistic or scientific study. Returning to England in 1719, Catesby's sketches revealed specimens, particularly plants, never seen before in the United Kingdom, and a number of leading British scientists encouraged Catesby to return to the colonies to resume documenting these finds with greater specificity. Catesby subsequently spent five years along the eastern seaboard and in the Bahamas applying more systematic methods of observation and documentation while simultaneously completing small watercolor-and-gouache paintings to record the flora and fauna he encountered. As he endeavored to publish his findings, Catesby could not afford to hire an engraver, so with the help of French artist, Joseph Goupy, he taught himself how to etch and transferred his watercolor paintings on to copper plates, later hand-applying color to each of the printed sheets these plates produced. This work culminated with the publication of 200 copies of a 220-plate oeuvre entitled Natural History, a process that took Catesby nearly eighteen years to complete.[2]

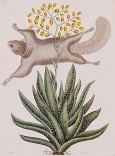

While Catesby was neither a trained scientist, nor a trained artist, the Milwaukee exhibit clearly highlighted the nuanced level of artistry and high degree of environmental sensitivity that Catesby brought to his interpretive work. A number of Catesby's prints, particularly Wampum Snake (with Catesby Lilly), attest to the important role Catesby played in identifying and recording botanical varieties previously unknown to English audiences (fig. 2). Moreover, his birds, snakes, and squirrels all seem to reflect human personalities as they are placed side-by-side with the novel botanicals that captured his attention. In one print, a yellow-breasted chat appears with a trillium that seems to be tickling its belly (fig. 3). In another, a miniature grey fox poses coyly underneath a flowering Indian pink (fig. 4). In yet another, a flying squirrel seems to defy gravity in order to call specific attention to the colorful beauty of a Bahaman bromeliad (fig. 5). These thoughtful portrayals emphasize Catesby's ecological aesthetic—his work cannot be viewed as mere "mug shots" or as rigid still-lifes—for he presented his subjects with powerful fluidity and he depicted them within interdependent environments, which the exhibit defined as a revolutionary approach for its time. Entries excerpted from Catesby's journals (and displayed next to his prints) drew more explicit attention to his emphasis on the interdependence of all species and the symbiotic nature of the environment he attempted to capture.

By opening their exhibit with such a rich narrative, the Milwaukee museum clearly framed the three related lines of inquiry it would continue to address throughout its exhibit. With an understanding of Catesby's ecologically-sensitive vision, the dedication that led him to document these natural wonders so carefully, and the intricate hand-coloring process he employed for almost two decades to produce such exquisite prints, viewers were able to more fully explore connections between Mark Catesby's prints and the collected works that were subsequently produced over the next century by Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon.

This initial portion of the exhibit concluded with a glass case display containing an original edition of Volume 2 of Catesby's Natural History, on loan from the Chipstone Foundation. With its pages opened to a beautifully speckled bullfrog drawn with such animation that it seemed ready to leap at any moment, this glass case held one of the highlights of the exhibit (fig 6). Another highlight included the framed copy of A Map of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands with Adjacent Parts that was completed by Catesby in 1733, and made available by anonymous loan. Both of these items further enriched visitors' understanding of the labor-intensive nature of Catesby's meticulous work and the evolving geographical boundaries he observed during a critical era of colonial expansionism.

Alexander Wilson, 1766-1813

Turning to the next portion of the exhibit, gallery visitors were invited to view nine framed prints attributed to Alexander Wilson. Although Wilson is not mentioned in the exhibit's title, his work remains a part of the museum's permanent collection and these specific frames established an illuminating contrast to Catesby's vibrant opening images. Exposed as a young man in Philadelphia to collections of Catesby's work, Scottish-born émigré Alexander Wilson was another respected American naturalist and is generally acknowledged to be the first American ornithologist. Settling near Philadelphia after his arrival in the United States in 1794, Wilson supported himself as a teacher, but dedicated his life to documenting his one true passion. He traveled extensively throughout the United States, often on foot, to pursue North American bird species.[3]

Unlike Catesby, Wilson hired professional engraver Alexander Lawson to transfer his original sketches on to copper plates for publication. Together Wilson and Lawson prepared a nine-volume treatise entitled American Ornithology, which was issued from Philadelphia in at least ten editions for more than seventy years.[4] To save money, Wilson and Lawson often needed to fit more than one bird on each printing plate, which produced a kind of representational stiffness that tended to make Wilson's birds look truncated and artificially posed, and his work, perhaps by necessity abandoned any effort to portray the animals' surrounding habitats (figs. 7 and 8). The kinds of paper available during this time period did not absorb pigment well, and as a result, although these prints were also hand-colored, they lack the depth and soft detail observed in Catesby's work. While the paper available for Wilson's prints and the more rigid printing process employed in America during the second half of the eighteenth century certainly produced less aesthetically pleasing surfaces than the work produced in England by Mark Catesby, the small sheaves prepared by Wilson were still able to provide important ornithological information for a burgeoning scientific community.

The Milwaukee exhibit was quick to point out that the flat nature of Wilson's visual work found a counterbalance in the lively prose he developed to accompany his printed images. A published poet influenced by fellow Scotsman, Robert Burns, Wilson's writing was filled with dramatic language as he "rambled" up river banks, lodged in "wretched hovels," and observed a "universal ocean of forest bounded only by the horizon." The written excerpts displayed in this portion of the show reflected moments of wonder, fear, and even extreme pleasure as Wilson encountered the infinite expanse of this "new world." One can only surmise that his narrative passages may have been influenced by the Romantic Movement in Western European art and literature, led in part by Robert Burns and the American, James Fennimore Cooper. Stressing strong emotions and the sublimity of an untamed landscape, these Romantic tendencies were clearly evidenced for exhibit viewers and further enriched their understanding of the artistic lens that shaped Wilson's work.

John James Audubon, 1785-1851

While the reputation of John James Audubon as a naturalist and as an artist has certainly cast a long shadow over the scientific and artistic legacies of Mark Catesby and Alexander Wilson, Audubon drew inspiration from the work of both men, and remained deeply indebted to them. Born in Santo Domingo (now Haiti) as the son of a French sea captain and a French chambermaid, Audubon arrived in America in 1803 and, like Wilson, also settled near Philadelphia. In 1820, facing bankruptcy as a result of several failed business ventures, Audubon decided to pursue his life-long interest in natural history and initially devoted his time to producing a complete record of American birds. He traveled for the next four years along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in search of species that may not have been included in the work of Alexander Wilson.

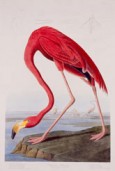

Unable to find a publisher in Philadelphia for his project, where Wilson's work was already being produced, Audubon then traveled to Great Britain in 1826. He subsequently contracted with printmaker William Lizars in Edinburgh, Scotland to make engravings from his original sketches and hand-color the resultant prints for American and European subscribers. A (fortuitous) strike held by the colorists in Edinburgh later drove Audubon to replace Lizars with a London printer, Robert Havell, Jr. in order to move more swiftly toward final production. Havell employed etching, engraving, and the process of aquatint wash, followed by hand coloring to complete Audubon's order. First developed in 1769, aquatint allowed for deeper, more textured color and produced exquisite detail in Audubon's work, made even more breath-taking by the large "Double-Elephant" sheaves of rag paper used for Audubon's prints (fig. 9).[5] The one-hundred percent cotton rag paper absorbed Havell's aquatint wash with ease and produced a beautiful luminescent quality that can still be observed easily today (fig. 10). Gallery visitors were able to compare these spectacular folio papers with six of the smaller "Royal Octavo" Audubon prints completed by lithographer John T. Bowen between 1839 and 1842. These smaller productions lacked some of the stunning color observed in the earlier Havell prints, but contained the same intricate detail and the same careful attention to each species' surrounding habitat which easily distinguishes Audubon's work from Wilson's.

As one of the most entertaining aspects of this exhibit, the Milwaukee Art Museum procured copies of Alexander Wilson's three-volume American Ornithology originally owned by John James Audubon. On loan from the Newberry Library in Chicago, these three volumes brought history alive in a provocative and moving way. Audubon's marginalia—tiny, penciled scrawls that emphatically refute or denigrate Wilson's findings—confirm the competitive business of "scientific discovery" and further allow contemporary audiences to peek for just a moment at the passions which undoubtedly drove each of these three men, both professionally and personally.

The Catesby, Audubon exhibit concluded with a series of hand-colored lithographs on loan from the Milwaukee Public Library that were prepared from original watercolors completed by John James Audubon, or his son, John Woodhouse Audubon between 1845 and 1848. The prints appeared in the elder Audubon's final project, a three-volume edition of The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America originally published in New York between 1845 and 1853. While lacking the color, detail, and clever animation found in most of his earlier work, these final prints specifically document the senior Audubon's fascination with the disappearing "frontier." Somber images, such as the Entrapped Otter canvas which foregrounds an otter's paw caught in the vice of a large, jagged metal trap, clearly evidenced the artist's growing concern for the survival of many natural species in the face of vast human encroachment (fig. 11). The otter's sharp, bared teeth seem to illuminate further the all too human emotions of anxiety and fear that may have been associated with such rapid cultural and ecological transformations.

The Milwaukee exhibit could have been enhanced had it been able to display some of the original copper plates that produced these intricate prints. In the same vein, for a show designed specifically to address visions of the "New World," this display failed to present more forcefully the imperialistic, and often hegemonic, nature of these scientific and artistic endeavors. Certainly, connections between the study of nature and empire building during this historic era are well documented.[6] Contemporary scholars affirm that these naturalist-artists relied on a European imperialistic aesthetic, which aligned directly with nation formation and often wreaked havoc upon local cultures and local habitats. For example, to create one good picture plate of birds for the international marketplace, Audubon had to shoot and stuff hundreds of them. The exhibit, which emphasized shifting visions of sensitive wonder, Romantic fascination, and finally nostalgia, failed to trouble the very notion of a "New World" or reference the ideology of exoticism and its related forms of "othering" that often produced disastrous results for indigenous populations.

Nonetheless, the Catesby, Audubon exhibit was intriguing for the manner in which it presented some of the other social, economic, and cultural complexities that scientists and artists encountered for almost two centuries as they endeavored to create and produce representations of the natural world. As visions of the American landscape shifted and commercial printing processes evolved, this exhibit demonstrated that at least three individuals found ways to transcend traditional, and often arbitrary, distinctions between art and science in order to produce a lasting legacy for both fields. The Milwaukee display highlighted, through both image and text, the important contributions to art and science that can be made through sustained effort and creative vision. Perhaps more importantly, the exhibit poignantly displayed the rich natural resources that our environment can unveil for those who dare to take the time to observe its treasures.

Paige A. Conley

University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

pconley[at]uwm.edu

[1] For example, the Frank H. McClung Museum in Knoxville, Tennessee is currently featuring its permanent collection of hand-colored copper plate engravings and lithographs by Mark Catesby, Alexander Wilson, and John James Audubon in an exhibit entitled Birds of the Smokies which began on January 2, 2009 and will run until December 31, 2009. The Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, Georgia also held an exhibition entitled Abbot, Audubon, Catesby, and Wilson: Naturalists in the South, which ran from June 30, 2007 through August 26, 2007. Like the McClung exhibit, the Morris Show focused on the work of these three artists and their expressions of regional habitats and culture.

[2] The complete title of Catesby's published work reflected the ambitious, complex nature of his project: The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands: Containing the Figures of Birds, Beasts, Fishes, Serpents, Insects, and Plants: Particularly the Forest-Trees, Shrubs, and Other Plants, Not Hitherto Described, or Very Incorrectly Figured by Authors; Together with Their Descriptions in English and French; to Which, Are added Observations on the Air, Soil, and Waters: with Remarks upon Agriculture, Grain Pulse, Roots, etc.; to the Whole is Prefixed a New and Correct Map of the Countries Treated of. It was issued as two volumes in London from 1731-1743.

[3] Some scholars estimate the Wilson may have traveled more than 10,000 miles on foot in search of North American bird species. Weakened by dysentery contracted during one of these trips, Wilson died in 1813 at the age of forty-seven.

[4] The full title of the Wilson, Lawson publication is American Ornithology; or, The natural history of the birds of the United States: illustrated with plates, engraved and colored from original drawings taken from nature. It was published in Philadelphia from 1810-1814.

[5] A typical sheet of "Double-Elephant" folio paper measures 29 1/2 by 39 1/2 inches.

[6] See e.g., Brückner, Martin. "The Critical Place of Empire in Early American Studies." American Literary History 15.4 (2003) 809-821; Meyers, Amy R. W. and Margaret Beck Pritchard, eds., Empire's Nature: Mark Catesby's New World Vision. (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).