The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

Alfons Mucha

Belvedere, Vienna, February 12 – June 1, 2009

Musée Fabre, Montpellier, June 20 – September 20, 2009

Kunsthalle der Hypo-Kulturstiftung, Munich, October 9, 2009 – January 24, 2010

Catalogue:

Alfons Mucha (German edition)

Edited by Agnes Husslein-Arco, Jean Louis Gaillemin, Michel Hilaire, and Christiane Lange; with essays by Jean Louis Gaillemin, Roger Diederen, Arnauld Pierre, Olivier Gabet, Dominique de Font-Réaulx, Alfred Weidinger, Lenka Bydžovská and Karel Srp, and Tomoko Sato. Munich: Hirmer, 2009.

355 pp; 379 color illustrations, 100 b/w; selected bibliography.

€38 ($52, in museum); €45 ($61, in bookstores).

ISBN: 978-3-7774-7035-1

Alfons Mucha (1860–1939) (French edition)

Paris: Somogy, 2009.

372 pp.

€39 ($53)

ISBN: 978-2-7572-0277-7

Alfons Mucha (English edition)

Munich: Prestel, 2009.

€50 ($65, £45, Can. $84)

ISBN: 978-3-7913-4356-3

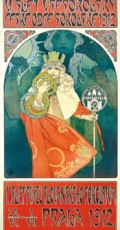

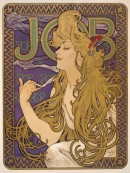

In early February 2009, a pair of images suddenly brightened the wintry Viennese streets (figs. 1 and 2). A super-sized detail of a poster printed in 1896 to sell JOB cigarette papers announced that the Belvedere was holding a major exhibition devoted to Alphonse Mucha, the first in the Austrian capital since 1897. His languid, ecstatic smoker has become an archetypal figure, identifiable at a glance as a Mucha woman, in striking contrast to the other advertisement for the show. Originally published in 1912 to promote a gymnastics festival, the second poster featured a crowned girl, eyes wide open, holding linden wreaths and a circular emblem with the motto Praga Caput Regni, denoting an allegory of Prague. The posters embodied two sides of Mucha (1860–1939)—the familiar graphic artist of the belle epoque and the forgotten Slav patriot—forcefully presented in this exhibition (fig. 3).

Displayed in giddy profusion throughout the city, the Belvedere publicity recalled the appearance in Paris around New Year's Day, 1895, of Mucha's Gismonda. The talented draftsman had depicted Sarah Bernhardt as Victorien Sardou's Cleopatra some years earlier in illustrations for Le Costume au Théâtre.[1] Days after her fiftieth birthday in October 1894, the latest Sardou vehicle for the actress had its first performances.[2]Gismonda then re-opened on 4 January—the evening before the public degradation of Alfred Dreyfus—and the seven-foot-tall lithograph chosen by the actress to promote the revival made Mucha famous. At the Belvedere, however, surrounded by so many other posters, the impression from the Albertina of that legendary pastel icon was somewhat lost on the wall (fig. 4).

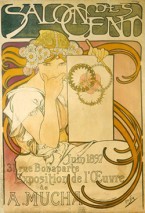

The poster sequence began with two smaller works suggesting the artist's growing reputation (fig. 5, right side). In early 1896 he created a poster for the Salon des Cent, the prestigious exhibition series sponsored by the journal, La Plume.[3] For his one-man show the following June at the same venue, he designed another poster (fig. 6). Rather than depict a voluptuous woman in dreamy reverie, Mucha chose an alert girl wearing a Moravian headdress to advertise his exhibition. Her embroidered cap and daisy crown restrain somewhat the coiling hair that came to be called Mucha's macaroni, and the poster contains an early hint of the Slavic allegories that would one day supplant the indolent beauties of the Latin Quarter (fig. 7).

Accustomed to its colossal enlargement on the streets of Vienna, visitors could easily overlook the much smaller original JOB in the exhibition (fig. 8). To market the convenient packets of paper, Mucha drew a chalky banner of smoke rising like an origami serpent from the cigarette tip, letting the O in the product name serve as a halo for his magnificent smoker. Green monograms on the lavender background preserve the original diamond shape between the J and B of earlier logos, the initials of Jean Bardou, founder of the firm; Mucha would re-use the monogram background in his later and larger JOB.[4]

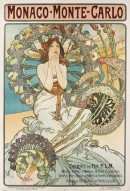

The hypnotic power of the halo and the circle, the arch and the horseshoe in Mucha's imagery emerged unmistakably in the first gallery, where repetitive disks and loops exerted the fascination of an astronomical clock. A railroad poster announced further components of the Mucha vocabulary: whirling, stem-spoked wheels, alive with birds, have burst into bloom as a fantasy train approaches the Mediterranean (fig. 9). Yet this diverse selection of posters lacked a core.[5] Even Bernhardt as Médée (with a delta D and Helios as a fierce orange halo), flanked by the fabulous life-size charcoal drawing from the Musée d'Orsay, did not have the expected impact (fig. 10). Instead of the divine Sarah, Queen Victoria was the focus of the room (fig. 11). Unidentified in either wall label or catalogue, the British monarch drew an audience perplexed by her colossal anonymity. Those who recognized Victoria could look at the label date of 1897 and recall the queen's Diamond Jubilee on the throne, and those who did not could relish the exuberant pasta manes of the heraldic lion and unicorn.

A teaching manual of 1902, Documents décoratifs, was the topic of the second room, where unfortunately none of the 72 final plates were on view, only studies and templates.[6] This important portfolio, as described by curator Jean Louis Gaillemin in his catalogue introduction (13), marked the end of Mucha's art nouveau period; in another astute essay, Olivier Gabet examines the process he calls the "Mucha Method." Although omitted from the catalogue reproductions, the template for Plate 35 was a treasure of the show; its delicious bands of squirrels in pine trees, pigeons in flight formation over an oak branch, and cockatoos perching before palm fronds are illustrated here in the completed plate (fig. 12). Had the exhibition included one strong color print—Plate 42, for example—it would have better illuminated the copious riches of the Documents décoratifs (fig. 13).

Small adjoining rooms housed works related to two earlier masterpieces of illustration. Both enchanting books were published by Henri Piazza and printed by the firm of Ferdinand Champenois, to whom Mucha was under contract. The first room included final sketches for Le Pater (1899), a volume Mucha ranked among his most important accomplishments.[7] In this theosophical meditation on evolution, Mucha gave each of the seven lines of the Lord's Prayer a three-page 'chapter' (reproductions at http://richet.christian.free.fr/pater/pater.html). Two pages were color lithographs: the first framed the verse in Latin and French within complex geometrical shapes, and the second presented a textual interpretation by Mucha as an illuminated manuscript. The third page was a symbolic drawing in black and brown hand photogravure (fig. 14).[8] These full-page drawings show human beings striving toward the light, where Nature takes the shape of a woman and God that of a youth, a vision that would clearly not receive an imprimatur from the traditional church. The other small room contained selected studies, trial proofs, and pages from Ilsée, Princesse de Tripoli (1897), a tale commissioned by Piazza from the aristocratic playwright Robert de Flers (1872–1927) and illustrated with 132 splendidly complex lithographs ( see http://richet.christian.free.fr/ilsee/ilsee.html ).[9]

The exhibition narrative, molded to fit the architecture of the Lower Belvedere, led to Room 3, with drawings for an unbuilt Pavillon de l'Homme intended for the Exposition Internationale of 1900, five of Mucha's anomalous dark pastels (c. 1900), and a body of earlier illustrations for Charles Seignobos's picture book of German history.[10] To approximate wood engraving, Mucha prepared grisaille-like oil studies on wood. An adjoining alcove was dedicated to the plates of Combinaisons ornementales (1902) and to Mucha's collaboration with the jeweler Georges Fouquet (1862–1957). Fouquet's new shop in the rue Royale in Paris opened in 1901; it was reassembled in 1989 for permanent display at the Musée Carnavalet. A photographic view of the reconstructed boutique set the scene for a display of four cartoons for stained glass windows, designs for façade medallions, furniture designs, and a vitrine with jewelry examples (fig. 15).

After bending to examine a peacock feather ring or a Byzantine comb, the viewer moved on to Room 4 and a dramatic change of scale. Two of the twenty paintings that comprise The Slav Epic (1911–28) dominated the main wall (fig. 16). Mucha's slavophile American patron, Charles Richard Crane (1858–1939), promised the municipality of Prague, in 1910, to finance the project on condition that the city would erect a permanent building needed to house the completed works. The first exhibition of five paintings—including both the canvases shown in the Belvedere—opened in April 1919 at the Klementinum in Prague, capital of the new Republic of Czechoslovakia.[11] Officially handed over to the mayor in September 1928, and made part of the Gallery of the City of Prague (Galerie hlavniko města Prahy) in 1963, the paintings have been kept since 1950 in the castle at Moravský Krumlov (between Brno and Mucha's birthplace, Ivančice). Plans to build the promised exhibition space remain uncertain.

Mucha's Svantovit Festival depicts a gathering of the Baltic Slavs before their temple at Cape Arkona on the island of Rügen (fig. 17). The chalk cliffs in the background (familiar from works by Caspar David Friedrich and other painters) are lit by a setting sun. The faces of the four-headed solar deity Svantovit, shown at the top with his linden branch and cornucopia, are cropped in all color photographs in the Mucha literature, including the present catalogue. Unaware of the future, the revelers below do not see the German god Thor with his wolf pack (upper left) invading the sanctuary. The last Slav warrior is dying, mourned by three musicians (fig. 18). Mucha knew that the Arkona temple had been razed by a Danish king in 1168, but his intuition of a menace from Germany was prophetic.

A very late work was documented in Room 5, a narrow corridor with watercolor cartoons for a stained-glass window in St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague. Commissioned by the Slavia Bank in 1931, the window shows a narrative style similar to Mucha's wall decorations in Room 6, painted three decades earlier in Paris for the Bosnia-Herzegovina Pavilion at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 (figs. 19, 20). A partial reconstruction of the dismantled murals, this room is the most original of the exhibition.[12] Alfred Weidinger explains in his catalogue essay the political constraints imposed on the painter by the Austro-Hungarian government, which had occupied the two provinces since 1878 (48–55). Rather than paint a historical panorama of Balkan history, the Czech artist in 1900 might have been expected to sculpt La Parisienne, the ephemeral woman atop the exposition's entry gate executed instead by Paul Moreau-Vauthier; Mucha had, in fact, planned such a figure for his Pavillon de l'Homme. But inspired by the suffering of the southern Slavs as he worked on the murals, Mucha, who turned forty that summer of the fair, took a new path in mid-life that led him to the Slav Epic and the wish to "talk in my own way to the soul of the nation."[13]

Returning to Prague in 1910 after several years spent mostly in the United States, Mucha accepted a commission to decorate the new Municipal House. His enthusiastic Pan-Slavism was unshaken by violent criticism from envious Czech artists, who reduced the extent of his participation to one ensemble: the Mayor's Hall. The Belvedere show ends in Room 7 with studies for its three large allegories, the ceiling, and the pendentives of heroes personifying national virtues; a single heroine, the mother of Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, stands for Maternal Wisdom. Although Mucha failed to reach the souls of his homeland critics, he persevered and achieved his goal. With the gift of The Slav Epic, he fulfilled his side of the promise to the city of Prague. Mucha died there in July 1939, a few months after the Germans invaded.

The Belvedere catalogue is the type of book described by libraries as "chiefly illustrations." Curator Jean Louis Gaillemin is known for his recent Design contre design exhibition at the Grand Palais in 2007–2008, which bravely abandoned chronology for a thematic arrangement.[14] For Alfons Mucha, the Austrian artist Peter Baldinger designed haphazard visual effects, sometimes enjoyable, sometimes negligent. More design intervention would have improved the text sections, where otherwise interesting essays run as dull blocks of print. The reproductions do offer delights for a patient reader: details of the Bosnia-Herzegovina murals and the St. Vitus window, for example, present Mucha the manga artist.[15] The book, however chaotic, reminds us that he was indeed a master, whether he drew sun gods or sugar tongs.

The span of his endeavors and a mid-course maneuver that led him toward his Slavic roots make Mucha a fascinating figure. To demonstrate the trajectory of the artist's ambitions and achievements—from the early illustrations to a cathedral window—is no easy task for curators of a retrospective. Only one decade of his work (1895–1905) is familiar to non-Czech audiences, and many art lovers today are as uncertain about Mucha's nationality as they were in Paris in the 1890s when a rumor circulated that Sarah Bernhardt had found him in a gypsy camp on the Hungarian steppes. The Belvedere exhibition achieved an admirable balance, reminding visitors of the known, and presenting opportunities to discover new aspects of the artist.

The reconstruction of the Bosnia-Herzegovina Pavilion offered a chance to see the murals far better than could fair goers in 1900, when the frieze hung much higher. Mucha's elaborate program for the Mayor's Hall in Prague's Municipal House can hardly be imagined through studies hung in a small museum room, but the exhibition nevertheless managed to suggest its significance. This series from 1910–11 is of interest in light of other controversial public mural projects from precisely that period by contemporaries who, like Mucha, had become famous for quite different work: the panels by Edvard Munch for the Oslo University Aula, for example, or Carl Larsson's stairwell for the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm.[16] The Belvedere and its international team can be commended for introducing a public familiar with the Mucha of calendars and fridge magnets to a more complex figure, a man with lofty ideals for humanity and a special devotion to his fellow Slavs.

Jane Van Nimmen

Independent scholar, Vienna

vannimmen[at]aon.at

[1] Among the wealth of resources on his remarkable site devoted to Mucha's graphic art, Christian Richet has included resizable images of the artist's illustrations for Le Costume au Théâtre in 1890-1891; see http://richet.christian.free.fr/costume/costume.

[2] On Mucha's illustrations of the earlier performances of Gismonda drawn for the magazine Le Gaulois in November 1894 and for a full documentation on the poster, see http://richet.christian.free.fr/gauloisgismonda/gaulois.html.

[3] The founding editor Léon Deschamps (1864–1899), his bimonthly journal, and its role in the recognition of art posters are discussed in Nicholas-Henri Zmelty, "Le discours critique de la revue La Plume sur l'affiche illustrée (1893–1899)," Image and Narrative [e-journal], 20 (2007). Available: http://www.imageandnarrative.be/affiche_findesiecle/zmelty.htm. See also Helen Bieri Thomson, with essays by Patricia Eckert Boyer and Jocelyne Van Deputte, Les affiches du Salon des Cent: Bonnard, Ensor, Grasset, Ibels, Mucha, Toulouse-Lautrec, exh. cat. (Gingins: Fondation Neumann, 1999).

[4] In an earlier JOB ad by Firmin Bouisset (1859–1925), the diamond had already grown into a capital O, framing the head of a chimneysweep. Mucha's pupil Jane Atché (1872–1937) exhibited a JOB in November 1896 in Reims, where her master showed seven posters; see Alexandre Henriot, ed., Catalogue de l'exposition d'affiches artistiques . . ., exh. cat.(Reims, 1896), no. 208. Atché added the brand name much as Bouisset and Mucha did, adapting the O to encircle the woman's head. An intriguing variant (before letters) transforms knotted smoke into a halo for her elegant figure; see the impression of Atché's JOB at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, available at: http://collectionsonline.lacma.org/mwebcgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=67141;type=101 . Claudine Dhotel-Velliet, who has written the first biography of the little-known artist from Toulouse (Jane Atché [Lille: Le Pont du Nord, 2009]), kindly shared with me her research on JOB. See also her article "Jane Atché (Toulouse 1872-Paris 1937): Le mystère," Nouvelles de l'Estampe, No. 219 (July-Sept. 2008), 41–44. I am grateful to Regeana M. Akers, Fine Arts Library, University of Texas Austin, for bibliographical support.

[5] The poster lover disappointed by the first room at the Belvedere could travel to Budapest to see an outstanding Mucha exhibition at the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum. In a Sarah Bernhardt chapel that opened the show, all seven of her Mucha posters lined up to awe the visitor. Appropriately hung and lit like monumental brasses, narrow as the coffin in which she claimed to sleep, they formed a paper sepulchral monument to the actress's carefully tended image. See Marta Sylvestrová and Petr Štembera, In Praise of Women: Alfons Mucha – Czech Master of the Art Nouveau (Budapest and Brno: Szépmüvészeti Múzeum and Moravská Galerie, 2009), in Hungarian and English. A Czech-English edition is to accompany the exhibition when it moves to Brno (October 16, 2009–January 24, 2010).

[6] In Budapest, by contrast, one could examine the multiple techniques, listed in Art et Décoration (October 1902), 3, as heliotypography, chromolithography, colors applied by hand or by stencil, and heliogravure (hand photogravure) in black and in color. See Geneviève Lacambre, "Les Documents décoratifs de Mucha" in Markéta Theinhardt and Pierre Brullé, eds., L'illustration en Europe centrale au XIXe et XXe siècles: Un état des lieux, Acts of a colloquium organized by the Centre Interdisciplinaire de Recherches Centre-Européennes (CIRCE), Université de Paris-Sorbonne (Paris IV), December 3-4, 2004 (Paris: CIRCE, 2006), Cultures d'Europe centrale, 6 (2006), 78–90. The cover, title page, and all plates are available at http://richet.christian.free.fr/docdeco/docdeco.html

[7]Le Pater: Commentaires et compositions de A. M. Mucha (Paris: F. Champenois / H. Piazza et Cie. L'Édition d'Art, 1899). See Anna Dvořák, Mucha, Le Pater: Illustrations pour Le Notre-Père, with contributions by Helen Bieri Thomson and Bernadette de Boysson, exh. cat. (Paris: Somogy; Gingins: Fondation Neumann, 2001), and Anna Dvořák, "Alphonse Mucha as Illustrator," in Victor Arwas, Jana Brabcová, and Anna Dvořák, The Spirit of Art Nouveau exh. cat. (Alexandria, Virginia: Art Services International and Yale University Press, 1998), 82–95.

[8]Le Pater: Commentaires et compositions de A. M. Mucha (Paris: F. Champenois / H. Piazza et Cie. L'Édition d'Art, 1899). See Anna Dvořák, Mucha, Le Pater: Illustrations pour Le Notre-Père, with contributions by Helen Bieri Thomson and Bernadette de Boysson, exh. cat. (Paris: Somogy; Gingins: Fondation Neumann, 2001), and Anna Dvořák, "Alphonse Mucha as Illustrator," in Victor Arwas, Jana Brabcová, and Anna Dvořák, The Spirit of Art Nouveau exh. cat. (Alexandria, Virginia: Art Services International and Yale University Press, 1998), 82–95.]

[9]Ilsée was printed in May 1897, just before the opening of Mucha's solo show at the Salon des Cent, where he exhibited all the original watercolors for the book (Nos. 176-312), along with ornamental letters (No. 313), more than a hundred sketches (Nos. 314-433), and a study for the frontispiece (No. 434).

[10] Charles Seignobos, Scènes et épisodes de l'histoire de l'Allemagne (Paris: Armand Colin, 1898). Mucha produced 33 single-page (hors texte) illustrations, and the Salon artist Georges Rochegrosse seven more. Georges Lemoine, a sought-after wood engraver, carved the blocks, and the Belvedere catalogue (246–52) includes four full-page blow-ups that demonstrate his skill. Mucha took pride in this project, showing drawings at the 1894 Salon des Artistes Français (Nos. 2490-2492), and in solo exhibitions at the Galerie de La Bodinière, Nos. 1-27 (February 16–March 10, 1897) and at the Salon des Cent, Nos. 103-116 (June 1897). See http://richet.christian.free.fr/seignobos/seignobos.html . The prominent historian Seignobos (1854–1942), like Mucha, suffered under the German occupation of his country; he died under house arrest in Brittany.

[11] The same five paintings shown in the Klementinum refectory (since 1929 the reading room of the Czech National Library) traveled to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1920 and the Brooklyn Museum in 1921, where an illustrated catalogue was produced by Christian Brinton (1870–1942). The most complete account of the series is Karel Srp, ed., Das Slawische Epos, exh. cat. (Krems-Stein: Kunsthalle Krems, 1994); some fourteen paintings and related studies were on view in that show. See also Lenka Bydžowska and Karel Srp, "Das 'Slawische Epos': Wort und Licht," in the Belvedere catalog, 57–63. Two different paintings will travel to Montpellier and Munich: The HolyMt. Athos and The Apotheosis of the Slavs, both from 1926 (according to Karel Srp in a telephone conversation with the author).

[12] Mural segments exhibited in Vienna are those from the Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague, and fragments of a lower frieze of vegetation that was part of the gift by the artist's son to the Musée d'Orsay in 1979. Fragments of the upper frieze on Bosnian myths, not displayed in Vienna, were also included in Jiří Mucha's gift; see Michel Laclotte, "Mucha au musée d'Orsay" in Mucha 1860–1939, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1980), 9–10.

[13] Mucha, "Úvodem" [introduction], Slovanská epopeje, exh. cat. (Prague: Česká grafická unie, [1928]); German translation in Srp, Slawische Epos, 63.

[14] Jean Louis Gaillemin ,Design contre design: Deux siècles de créations, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2007). This glossy pink-covered catalogue is itself a clever design object, rendered usable through careful captions and annexed lists. Gaillemin is also the author of Egon Schiele: Narcisse écorché (Paris: Découvertes Gallimard Arts, 2005), a subtle and poetic monograph with a perfect subtitle.

[15] The Belvedere catalogue lacks an index, but a more serious defect is its unwieldy checklist (231 numbered, plus 68 unnumbered entries) with no indication of where objects, such as the bust Nature from Karlsruhe (cat. 114) or the pendant from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (cat. 122), were actually shown. They were not in Vienna, but may or may not be seen in Montpellier or Munich, where presumably the fascinating photographs of models (cat. 211-231) will also be exhibited. The Budapest catalogue (In Praise of Women, as in note 5) with object entries, though not flawless, is more rewarding.]

[16] Edvard Munch returned to Norway in the spring of 1909, determined to win the competition for the Aula murals. Although three designs were accepted and executed, the refusal of The Human Mountain/Towards the Light ( http://www.munch.museum.no/content2.aspx?id=88&mid=85&lang=en ) led him to work on the painting for decades to come. Similarly, Carl Larsson completed a triumphant march of Gustav Vasa for the 1905 stairwell commission, then, to his bitter regret, the museum rejected its pendant Midvinterblot, begun in 1911 and depicting a Swedish king's sacrifice of his own life to appease the god Thor (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nationalmuseum_trappa_2008b.jpg ). Since its purchase by the museum in 1997, Midvinterblot has hung in its intended place.