The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

| Please note: selected figures are viewable by clicking on the figure numbers which are hyperlinked. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall—An Artist's Country Estate

A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Last spring, museum-goers in Manhattan were treated to complementary, "jewel-box" exhibitions that reassessed the work of the American artist and designer Louis Comfort Tiffany and his glassmaking company Tiffany Studios. Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall—An Artist's Country Estate was on view for six months at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and, just across Central Park, A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls had an extended four-and-a-half month run at the New-York Historical Society. Unfortunately, neither show traveled, limiting the exposure of these lavish feasts for the eye. Both exhibitions were thematically arranged, multi-media extravaganzas, featuring elaborate installations of decorative arts, including leaded-glass windows, mosaics, lamps, pottery, and enamelwork; however, the size of the shows and their approaches to the material diverged considerably. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall, a spring 2007 blockbuster exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art sponsored by Tiffany & Co., presented 238 objects and included a full-scale reconstruction of the Daffodil Terrace. Organized by Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, a Tiffany specialist and the Anthony W. and Lulu C. Wang Curator of American Decorative Arts at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in collaboration with The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art in Winter Park, Florida, Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall focused on the grand country estate in Oyster Bay, Long Island, designed and furnished by Tiffany, and tragically destroyed by fire in 1957. With the aid of period photographs, surviving architectural elements and windows, and extant objects integral to the interior displays at Laurelton Hall, Frelinghuysen sought to "shed new light on Tiffany's estate—its design, architecture and grounds, interiors, and collections of artwork" and to celebrate his unique and innovative artistic vision.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A New Light on Tiffany, in contrast, was a much smaller show, consisting of approximately 60 works, mostly lamps, accompanied by preliminary sketches for designs, ephemera, and period photographs. This aptly titled exhibition, co-curated by three Tiffany scholars, Martin Eidelberg, Professor Emeritus of Art History at Rutgers University; Nina Gray, an independent curator and Tiffany scholar; and Margaret K. Hofer, Curator of Decorative Arts at the New-York Historical Society, aimed to revise the conventional idea of Tiffany as the sole creative genius behind Tiffany Studios by exploring the critical role of Clara Driscoll (1861–1944), head of Tiffany Studios' Glass Cutting Department, and the young women she managed, known as the "Tiffany Girls." Drawing on Driscoll's recently discovered correspondence from the period of her employment at Tiffany and supplementary archival material, this show re-presented well-known Tiffany windows, mosaics, lamps, fancy goods, enamels, and pottery as the work of the "Tiffany Girls" and addressed Driscoll's experience as a woman at Tiffany Studios and more broadly in New York City at the turn of the twentieth century. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not surprisingly, the organization of the exhibitions and their ultimate goals were dictated by the holdings and interests of the sponsoring institutions. Laurelton Hall has had a presence at The Metropolitan Museum of Art since 1980 when its four-column loggia with multi-colored glass and pottery, floral capitals was installed in the American Wing's Engelhard Court after generously being given to the museum by Hugh F. and Jeannette G. McKean who salvaged it from the fire. This exhibition both illuminated the broader artistic and architectural context for the loggia and showcased The Metropolitan Museum of Art's extensive Tiffany holdings (the checklist for the show features at least 43 objects belonging to the museum). Linda S. Ferber, Vice President and Museum Director of the New-York Historical Society, articulates a similar concept, noting that A New Light on Tiffany "provide[d] an entirely new context for understanding and interpreting the Society's great Tiffany collection, one of the world's largest holdings of Tiffany lamps."2 Moreover, framing the exhibition around Clara Driscoll as a New York working woman fit perfectly with the historical society's mission to "make history matter" and to highlight the personal histories of New York's residents. Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall concentrated on mainly aesthetic issues related to Laurelton Hall and its presentation as a fully integrated work of art whereas A New Light on Tiffany emphasized the historical and social context of its objects and related them to broader class and gender issues. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall was the first exhibition to explore Tiffany's dream home. It included a number of works from public and private collections never before publicly displayed and many objects from The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art rarely shown outside Winter Park, Florida. Built between 1902 and 1905, after Tiffany received a considerable inheritance from his father Charles Lewis Tiffany, the founder of Tiffany & Co., the estate was conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk. It consisted of a main house with eight levels and 84 rooms, surrounded by terraced gardens, fountains, pools, stables, tennis courts, greenhouses, a chapel, a studio, and an art gallery. This self-sufficient residence "was ever evolving"; Tiffany eventually transformed it from a private home to the site of the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation, an organization that he established in 1918 to provide education and support for young artists (p. 3). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The exhibition, assembled thematically in the seven galleries of the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Exhibition Hall on the second floor of the museum, concentrated on three of the most celebrated rooms (the Fountain Court, the Daffodil Terrace and adjoining dining room, and the "forest room" or living hall) and on Tiffany's collections that he used to decorate his palatial home. Thus, it was divided between evocations of particular spaces at Laurelton Hall designed by Tiffany and presentations of specific collections compiled by him. In addition, the show began with a gallery installed with purchased and self-designed works used in the décor of his earlier homes. Each gallery contained a mixed-media display that, together with the built-in shelving and temporary walls, small groupings of objects, and atmospheric lighting, roughly recreated the character of a domestic interior. Viewers, however, had to depend on the period photographs of Tiffany's various residences to understand the actual layout of the spaces and arrangement of the objects. As a result, to fully comprehend the show, they had to engage in a visual game of matching the real objects to their photographic representations. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The introductory gallery, where visitors could purchase audio guides, set the subject and tone for the exhibition. On the far wall beneath the show's title was a wall-sized exterior view of the south side of Laurelton Hall. In front of this enlarged 1920s black and white photograph of the estate's loggia, visitors were greeted by a pair of large, glazed stoneware Kangxi-era lions (fig. 1). Now in a private collection in Switzerland, these guardian lions once belonged to Tiffany and were installed flanking the loggia at Laurelton Hall. Wedding the loggia's Indian architectural elements with the Chinese stoneware lions immediately revealed the cosmopolitan and exotic nature of Tiffany's taste and his appreciation of well-crafted, vibrantly colored objects that transform natural forms into art. Spectacle aside, it was surprising that this initial introduction to Laurelton Hall did not include any architectural plans and that visitors had to wait until the second to last gallery to see blueprints and elevation drawings. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

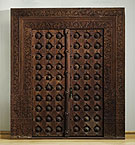

| Leaving behind the light-filled introductory space, viewers moved into a dimly lit gallery with deep vermillion walls filled with an eclectic array of objects that once belonged to Tiffany and formed part of the interior décor of either his apartment in the Bella Apartments at 48 East Twenty-sixth Street or the Tiffany house at Seventy-second Street and Madison Avenue. Featured here were rare objects that Tiffany purchased for his residences, including intricately carved teakwood doors from Ahmadabad, India, furnishings that he designed such as the plain, unadorned breakfast set, and pictures created by Tiffany that represent women in his studio, including a pastel of his wife, Louise Tiffany, Reading (1888) (fig. 2, fig. 3, fig. 4). This selection of works suggested Tiffany's interest in contrasting artistic traditions: pieces that evoked the Aesthetic Movement's harmonious blending of cultures and embrace of elaborate patterns were juxtaposed with the Arts and Crafts Movement's more restrained designs. The display also showcased Tiffany's experimental approach to conventional forms and materials as best seen in the leaded-glass window for the Bella apartment, "the earliest domestic window by Tiffany known to survive" and donated to The Metropolitan Museum of Art by the Tiffany scholar Robert Koch in 2002 (fig. 5) (p. 13). Combining diverse types of experimental glass—opalescent, marbleized, confetti, crown, and rough-cut jewels—he transformed the often static and representational imagery of stained glass into a bold, organic, dynamic pattern that seems to anticipate twentieth–century abstract painting. Both this window and the Steinway piano, whose intricately patterned, ivory-inlaid wood case Tiffany designed, were exhibited publicly here for the first time (fig. 6). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Although the purpose of this gallery—to explore interior design precedents for Laurelton Hall—was worthwhile, its layout was confusing, and its placement interrupted the flow of the show. Not until the visitor reached the wall text with the heading "Tiffany's Earliest Interiors" midway down the right hand wall did the significance of the objects in this room become clear. Visitors entering this space guessed that "these [objects] must have survived the fire" at Laurelton Hall, and many left without understanding the gallery's significance. Showing these objects along with several from Laurelton Hall would have made a more direct connection between Tiffany's early and late interiors. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In the next gallery, museum-goers encountered an interpretation of the Fountain Court or Moorish Court, the first of several highlights of rooms at Laurelton Hall. The Fountain Court, called the "soul" of Laurelton Hall, was an immense three-story space, measuring thirty-eight by thirty-nine by thirty-nine feet, with a fountain as its centerpiece (fig. 7). According to the wall text, it was a multi-functional space, acting "as one of the three principal rooms, as the entrance hall, and as an extension of the gardens." Inspired by Islamic architecture, its octagonal inner space supported by columns recalled the arrangement of an Islamic bath; its blue and green palette and its cypress tree wall pattern suggested a tile mural at Istanbul's Topkapi Palace; its tripartite niches resembled the muqarnas or "stalactite" vaults at the Alhambra. Although the room was sparsely furnished with wicker chairs and small hexagonal tables, Tiffany covered the floor with bear-skin rugs and Oriental carpets, filled the niches with some of his own Favrile glass and pottery, and surrounded the fountain with seasonal floral arrangements (pp. 71, 84, 86). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The installation in this gallery merely hinted at several of the key elements in the original Fountain Court. An unadorned wood replica of the base of the central fountain held the original four-foot-high, teardrop-shaped vase, but the basin contained no running water, and the plantings were limited to four baskets containing spathiphyllum with no flowers (fig. 8). Two wall vitrines with stepped outlines suggested the muqarnas-like niches in the original room; stenciled wall fragments that survived the fire along with several still extant Favrile glass hanging globes alluded to the wall decoration and lighting, respectively; and the only painting exhibited in the Fountain Court, a portrait of Tiffany with his dog in his garden at Laurelton Hall, which he commissioned from the Spanish artist Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida in 1911, was installed alone on the wall as in the actual space (fig. 9, fig. 10, fig. 11). Two glass cases with additional material flanked the entrance doorway: one contained a spectacular Aquamarine water lily vase, probably inspired by the water lilies at Laurelton Hall, but otherwise unrelated to the Fountain Court, and the other presented the personal notebook of Leslie N. Nash, who helped to build the fountain, and a pair of color wheels used to alter the tone of the water running through the teardrop-shaped vase. Sadly, this stripped down recreation did not begin to capture the resplendent atmosphere of the original space, described by Tiffany's contemporary Clara Brown Lyman as "charming enough by day, but by night a veritable Arabian Night's dream come true. . ." (p. 88). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The succeeding two galleries showcased Tiffany's collections. In one room his Asian and Native American objects appeared together followed in the next room by works in a variety of media he designed and/or created himself. The installations in the galleries drew on Tiffany's original arrangements of objects, as seen in the period photographs on the wall texts (fig. 12). For example, artifacts from China and Japan were juxtaposed in aesthetically pleasing, mixed-media arrangements, the California and Pacific Northwest coast baskets were placed side by side on shelves, and Tiffany's own blown glass vessels and pottery vases were housed in vitrines lined with a shimmering blue silk similar to that used at Laurelton Hall (fig. 13, fig. 14, fig. 15). Although the separation of these galleries by culture evoked Tiffany's own creation of rooms characterized by a particular aesthetic tradition, it did not allow for direct comparisons between Tiffany's creations and the things he collected. That said, seeing this many of his acquisitions for the first time led to a more nuanced understanding of his widespread sources of inspiration, and as the catalogue explicates, some of the works he made directly copied designs or derived their patterns from objects he owned (pp. 157, 180). But again, the exhibition did not foster a comparative examination because his collections were isolated from his creations. Viewers had to keep in mind the flora and fauna decorations on the Asian objects when they looked at Tiffany's enamelware in the next room, and likewise, had to remember the Qing dynasty headdress and tiara with kingfisher feathers when they arrived two galleries farther along to see the Peacock Headdress worn at the Peacock Feast at Laurelton Hall on May 15, 1914 (fig. 16, fig. 17, fig. 18). Besides eschewing the relationship of Tiffany's collection to his work, these galleries did not address at length the means by which he acquired these objects and the influence of dealers such as Siegfried Bing and the Fred Harvey Company, and friends, including the artist Lockwood de Forest. It is puzzling that these subjects were investigated in the catalogue but not in the exhibition itself. The decision to group together all of the objects Tiffany designed or made into one gallery did capture his talents and expertise in a wide-range of media (fig. 19). This idea, however, already has been underscored in other exhibitions and publications, including Frelinghuysen's Louis Comfort Tiffany at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1998), and by The Metropolitan Museum of Art's presentation of Tiffany on their website. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In the sixth gallery, the bountiful display of objects in Tiffany's collection gave way to a sparse room that featured a reconstruction of the Daffodil Terrace and a vignette of the adjoining dining room with its marble chimney breast and plainly designed dining set that recalled the breakfast table and chairs from the second gallery (fig. 20, fig. 21, fig. 22). A late addition to the house, the Daffodil Terrace was built around an existing pear tree, as seen in an enlarged black and white period photograph (fig. 23). Tiffany designed it to mediate between the dining room and gardens, the interior and exterior of the house, and the built and natural environments. Reconstructed here for the first time with the Wisteria leaded-glass panels that connected it to the dining room, the Daffodil Terrace dominated the space with its marble columns topped by capitals in the form of yellow glass daffodil blossoms sprung from green plate-glass stems (fig. 24, fig. 25). In contrast, the installation of the rest of the gallery seemed unharmonious and unsatisfying; along one side were architectural drawings, impossible to see because of the glare on the protective glass, and on the opposite side was a reading table with copies of the catalogue (fig. 26). In one corner appeared a wooden model for a smokestack in the shape of a minaret, and in the other, the rock crystals from one of the fountains in the garden surrounded by studies for the capitals of the loggia (fig. 27, fig. 28). One of the most exquisite objects in the entire show—the Peacock Headdress worn at a dinner that Tiffany hosted—was virtually lost in the corner at the far end of the gallery next to the dining room vignette (fig. 18). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The final gallery was dedicated to the "forest room" or living hall at Laurelton Hall (fig. 29). As in the original room, it contained a retrospective of Tiffany's work in stained glass, including his early window Feeding the Flamingoes (c. 1892), his Four Seasons panels, first exhibited at the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, and his late window Snowball (c. 1904) (fig. 30, fig. 31, fig. 32). In addition, the living hall's still extant lighting fixture with its hanging "turtleback" lampshades and two emerald-colored orbs was positioned over a glass case containing a Tiffany desk set, mirroring its original installment by Tiffany over a huge desk in the center of the room (fig. 33). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In general, a tinge of sadness, even nostalgia, seemed to haunt this exhibition. It reminded viewers that all that remains of Laurelton Hall are period photographs. Although nothing can substitute for the actual objects like the lions at the entrance, which survived because they were sold at the 1946 Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation auction, or architectural fragments and windows salvaged from the fire by one of Tiffany's former students, Hugh F. McKean and his wife Jeannette, I wonder whether the attempt to reconstruct the highlights of the home was as instructive as a documentary film with architectural plans and photographs or a digital recreation might have been.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catalogue Many of my criticisms of the exhibition, particularly its lack of information about individual works, its rough reconstructions of rooms, and the missed opportunity to juxtapose objects Tiffany designed and collected, were addressed by the catalogue, which serves as a valuable resource for scholars and Tiffany enthusiasts. Beautifully illustrated, the book consists of eleven essays, seven of which are written by Frelinghuysen and the remaining four by specialists in architecture (Richard Guy Wilson, Commonwealth Professor of Architectural History, University of Virginia, Charlottesville), in Asian art (Julia Meech, Independent Scholar and Consultant to the Department of Japanese Art, Christie's, New York), in Native American art (Elizabeth Hutchinson, Assistant Professor of American Art History, Barnard College/Columbia University, New York), and in the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation (Jennifer Perry Thalheimer, Collections Manager, The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art, Winter Park, Florida). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The catalogue is organized like the exhibition: beginning with Tiffany's earliest work in interior design in his homes in New York City and then analyzing the architecture and décor of his country residences, including Laurelton Hall. Moving on to the history of the collections exhibited at the estate, it culminates with two chapters that address life at Laurelton Hall— the first discusses farming, recreation, and entertaining, and the second explores the transformation of the house into an educational institution sponsored by the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation. An epilogue by Frelinghuysen briefly addresses the adoption of Laurelton Hall as a cinematographic setting for Tiffany's own family movies and for a silent film called The Beggar Maid (1921) and traces the tragic history of the house after Tiffany's death—the dispersion of its collections, the sale of the property, and the fire that finally destroyed it.4 Essays are supplemented with a chronology of Tiffany's life by Barbara Veith, a comprehensive bibliography, and a checklist of works in the exhibition. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In her introduction, Frelinghuysen describes the book as "a biography of sorts— not of a person but of a house" (p. 7). Her essays consist of detailed descriptions of the layout of the home and its contents and assume the character of an illustrated house tour, leading readers from room to room, object to object, describing the origins of the décor and collections. Her comprehensive coverage of the estate is remarkable, but her texts could benefit from more analysis of Tiffany and his home in the context of his times and in light of recent research on collecting practices in the United States at the turn of the century. Wilson's chapter, "Mysticism, Alchemy and Architecture: Designing Laurelton Hall," expands significantly on the exhibition's scant material about the house's architecture. He distinguishes Tiffany's approach to architecture at Laurelton Hall from that of his contemporaries, stating that his eclecticism was "not the academic eclecticism of, say the École des Beaux-Arts-trained Charles McKim (1847-1909) but one of emotion and synthesis" (p. 74). Rather than reproducing historic styles, Tiffany combined them in "reductive and abstract" ways (p. 74). Wilson also convincingly argues that Laurelton Hall revealed Tiffany's embrace of mysticism and alchemy and ultimately was designed to evoke a feeling of transcendence, transporting its visitors to "a larger world beyond" (p. 78). The two chapters by Meech and Hutchinson address at length for the first time Tiffany's collection of Asian art and Native American art, respectively. The authors uncover the networks of dealers, auction houses, and collectors with whom Tiffany was involved as well as the prices he paid for some of the pieces. Using period photographs and descriptions, they also delineate as best they can the presentation of the objects at Laurelton Hall and the influence of Tiffany's collections on his work. Notably, as Meech and Hutchinson explicate, Tiffany's acquisitions did not always conform to popular taste; he purchased thousands of tsuba (swordguards), using them to decorate the walls of his estate, but he never had a serious collection of ukiyo-e. He owned "an old-fashioned style" Kwak'wakw'wakw totem pole from British Columbia, which he placed in the drive leading to the house, rather than one of the newer, more elaborately carved versions from southeastern Alaska, favored by most collectors of this period (p. 177). Thalheimer, the Collections Manager of the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum, draws on her museum's archival resources, especially the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Minutes, to offer new insights into the goals and workings of this organization established in 1918. Conforming to Tiffany's beliefs, the foundation promoted painting en plein air. As an acceptance letter received by Hugh F. McKean states, "All artists who enter the Foundation are expected to devote themselves almost entirely to landscape work and no models will be provided" (p. 207). It is interesting to learn about the many turn-of-the-twentieth-century American artists who were involved as advisers to the foundation (Cecilia Beaux, Daniel Garber, Childe Hassam, Paul Manship, among others) or who were trained there (Paul Cadmus and Luigi Lucioni). The new research by the catalogue authors, the new photography of many objects, and the inclusion of architectural plans and period photographs make this catalogue a noteworthy addition to the ever expanding literature on Tiffany. Although this volume may not dramatically alter our understanding of Tiffany and his vision, it lays the groundwork for future analyses. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A New Light on Tiffany In contrast to the Tiffany exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, A New Light on Tiffany was a small, tightly focused show arranged thematically by medium in three, subdivided galleries on the first floor of the New-York Historical Society. The separation of the galleries into smaller spaces offered an intimate viewing experience but at times a crowded one. To articulate their revisionist approach to Tiffany, and to acknowledge publicly for the first time the work of his designer Clara Driscoll and the "Tiffany Girls," the curators relied heavily on Driscoll's "round robin" correspondence with her mother and sisters and on other archival documents, including Mary Jeroleman's Glass Selectors Ledger. As a result, it was imperative that viewers read the wall texts and the labels or listened to the audio guide to understand the reattribution of the works and the process of their production. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The introductory gallery presented Clara Driscoll as both a gifted manager and a talented designer (fig. 34). Her management skills were highlighted by a "round robin" letter, describing the meeting of the Women's Glass Cutting Department to discuss the new contract system at Tiffany Studios in 1898. As the letter explains, rather than simply imposing the rules of the new contract, she allowed her workers to air their grievances, and set a more relaxed tone for this gathering by bringing two quarts of ice cream. Besides emphasizing her ability to direct her staff, this entrance space showcased an example of the Dragonfly lamp, arguably Driscoll's most celebrated design and the only one for which she was publicly acknowledged, in a 1904 New York Daily News article about highly paid women (fig. 35). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The gallery opening off to the left of this introductory space reminded visitors that they were in a history museum where biography and historical context are essential to the presentation of art and artifacts. This second room, titled "The New York World of Clara Driscoll," sought to capture the diversity of Driscoll's experiences as a New York working woman at the turn of the twentieth century. It featured the latest fashions for the "New Woman" of the time—a cotton shirtwaist and long wool skirt and a bicycle suit; ephemera related to her personal life, including photographs of her boarding house at Irving Place and 16th Street, playbills and theater posters from productions she saw; and a recording of her favorite opera singer performing an aria from Richard Wagner's Das Rheingold (fig. 36, fig. 37, fig. 38). The juxtaposition of these artifacts with quotations from her letters on the wall labels illuminated Driscoll's cosmopolitan lifestyle in a rapidly evolving New York City. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Having established Driscoll's historical context, the next gallery shifted to an exploration of Tiffany and Driscoll's professional relationship. Although Driscoll worked independently or together with other women, most frequently with Alice Gouvy, she consulted Tiffany for critiques and final approval of her designs. The Butterfly lampshade, installed in a case just inside the gallery entrance, exemplified the kind of back and forth repartee they shared when deciding on designs (fig. 39). Quoting from Driscoll's account of the design development of this lamp, the text label explained that she based her idea for this lamp on her own recollections of her Ohio childhood, specifically her memories of butterflies flying over a field of yellow primroses. She shared her idea with Tiffany, who already had created his Butterfly window, and he told her to develop the design. Such vignettes drawn from Driscoll's correspondence enlivened the exhibition by providing a glimpse behind-the-scenes at Tiffany Studios and by revealing the personal response to nature that underscored some of the patterns. The wall texts also provided background information about the Four Seasons Windows on exhibit in Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall, discussing how Tiffany, who was sick in bed, conveyed his ideas for the Snow or Winter panel to Driscoll, who ensured that the window was executed to his liking (fig. 40). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The remainder of this section of the gallery placed Driscoll's and Tiffany's artistic collaboration in the context of a brief history of the Women's Glass Cutting Department, inaugurated in 1892. The presentation began with the department's participation in the creation of leaded-glass windows, represented here by The Reader (c. 1897) and several photographic reproductions of other works not available for loan to the show. An enlargement of a period photograph of a woman at Tiffany Studios creating a cartoon for a window highlighted the role played by women in the early phases of production (fig. 41). As the wall text elaborated, the initial stages of drawing cartoons and selecting and cutting glass involved women, but the final assembly, which required soldering and more intense physical work, fell to the men. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Furthering the theme of women's work at Tiffany Studios, the next section of this gallery was divided by medium and explored in succession mosaics, lamps, fancy goods (boxes, "tea screens," desk accessories, and candlesticks), pottery, and enamelware (fig. 42, fig. 43). Examples of each type of object appeared in free-standing vitrines and in wall cases throughout the room. Wall texts offered essential information about shifts in production and the changing responsibilities of women at Tiffany Studios as Driscoll initiated designs for new kinds of objects in late 1897. As time passed, the Women's Glass Cutting Department concentrated their efforts on the design and production of lampshades and mosaic bases. Building on her earlier experience with mosaics, Driscoll arrived at the idea of decorating the bronze bases for the lamps with glass mosaics, exemplified here by her inlaid-mosaic bases for the Deep Sea and Cobweb lamps (fig. 44). In the case of the Deep Sea lamp, her correspondence was very effectively juxtaposed with the work, enabling visitors to compare her quick sketch of the design in her letter with the final version. This pairing would have been even more instructive if the curators had transcribed her letter, in which she explained that the tanks at the Fisheries Building at the World's Fair in 1893 served as her inspiration. The emphasis on process continued in the fancy goods display, which was accompanied by a wall text that articulated the various phases of production (fig. 45). After conceiving the design for each type of object, Driscoll carved prototypes in plaster and wax and then sent these models to the foundry in Corona, Queens, where men cast them in bronze. This explanation was visually reinforced by a staged photograph of Driscoll creating a mold as her chief assistant, Joseph Briggs, stands by her side apparently listening to her instructions (fig. 46). The final section of this room expanded its investigation of women at Tiffany Studios through a presentation of the work created by Alice Gouvy, Lillian Palmié, Miss Lantrup, and a small group of women in the enamel and pottery departments. Just before 1900, Tiffany expanded production into these media and established a small workshop in Corona, Queens, near the Tiffany Studios foundry. As quoted on the text panel, Driscoll referred to this place as "a little Arcadia": both the feminine character of the small building with its "beautiful studies on the walls and vases of seed pods and dried leaves and every kind of lovely thing in Nature and Art" and the less commercial and less demanding nature of its production appealed to her (p. 89). Small enameled boxes and bowls decorated with fruit and flower designs, semi-porcelain vases with floral patterns, and watercolor sketches of plants and flowers by Alice Gouvy and Lillian Palmié offered viewers a sense of the natural motifs that prevailed in the work of these women (fig. 47). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The next gallery, divided into two spaces, focused exclusively on the lamps and their production (fig. 48). This long, narrow space was lined on either side with multiple versions of the Poppy, Dragonfly, Wisteria, Peony, among other designs (fig. 49). The show seemed a bit monotonous here with one lamp after another having only slight variation, but the significance of this assembly line arrangement did drive home a point. By juxtaposing several Dragonfly or Poppy lamps, visitors could observe often subtle changes in color, pattern, and light effects within the same design and among the different types: the filigree, for example, went underneath the glass in the Poppy lamp and over the glass on the Dragonfly model, creating two distinct visual effects. The alterations in color and type of glass from one lamp to the next revealed the handiwork involved and suggested that these lamps were not simply the result of a straightforward mechanical and commercial process; their success depended on informed aesthetic decisions. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Watercolor, black ink, and graphite studies and cartoons for lampshades illustrated how the lamps were altered, often simplified, from initial study to finished product: in an early sketch for the Poppy shade, seed pods are fastened around the top edge but are eliminated in the final version on view (fig. 50). The line-up of lamps was accompanied by several cases that contained materials used in their construction and detailed accounts of their assembly, taken directly from Driscoll's correspondence. A case in front of the Dragonfly lamps displayed the brass filigree and pressed-glass jewels used to create the dragonflies, and another case had samples of the glass (confetti, rippled, mottled, streaky, and drapery), glass-cutting tools, and the copper foil that served to encase the cut glass before it could be soldered (fig. 51, fig. 52). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Another section in this gallery addressed the effect of gender on production. Driscoll had several men working in her department to assist with the more physical tasks, and she also coordinated the production of her Glass Cutting Department in Manhattan with the factory in Corona, Queens, "staffed solely by male workers" (p. 117). The men were responsible for casting the bronze bases and for assembling the shades, and eventually they also worked on the lampshades with geometric designs. Featured in the section on the men's department were a geometric lampshade and a wooden block used to arrange the cut glass pieces of the lamp before soldering (fig. 53). As one text label explained, a rivalry developed between the men's and women's departments, and an ugly battle with the local, all male Lead Glaziers and Glass Cutters' Union ensued. After an unsuccessful attempt by the union to close Driscoll's department, an agreement finally was reached in 1903, limiting its number of female employees. An interesting aside was the constant turnover in the staff since married women were not allowed to work in the department. In fact, Driscoll had three separate tenures at Tiffany Studios that were framed by her marriage to Francis S. Driscoll, her unsuccessful engagement to Edwin Waldo, and her second and final marriage to Edward Booth in 1909. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The exhibition concluded with an epilogue in an adjoining space decorated with additional lamps. The focus was a large text panel with a stunningly long list of names of women known to have worked in the Glass Cutting Department (fig. 54). This list recognized the numerous women whose names have been recovered with the aid of Driscoll's correspondence and Mary Jeroleman's Glass Selectors Ledger. With this public acknowledgment of the "Tiffany Girls," the curators ended the exhibition by calling for future investigations of the—before now—nameless female employees of Tiffany Studios (fig. 55). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catalogue The catalogue enhances the material presented in the exhibition, offering more extensive analysis of the production of the objects and Clara Driscoll's role as a manager and a "New Woman" in New York. In doing so, like the exhibition, it depends on the prolific writings of Driscoll, who, in contrast to Tiffany, wrote long missives filled with intriguing details about her designs and their manufacture. In fact, each of the main chapters begins with a long quotation from one of her letters. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Divided into three chapters co-written by the three curators, the text escapes the sort of repetition that often occurs in multi-authored catalogues. It also contains an introduction with a short biography of Driscoll and an appendix, "The Women of Tiffany Studios," which includes brief biographies of more than sixty "Tiffany Girls," primarily compiled from Driscoll's correspondence and Mary Jeroleman's Glass Selectors Ledger. In the introduction, readers learn about Driscoll's early training as a designer at the new Western Reserve School of Design for Women and later at The Metropolitan Museum Art School and about her "three tenures at Tiffany, each of which was delimited by engagement and marriage" (p. 14). Despite the fact that her surviving correspondence only begins in the fall of 1896, the curators did their best to piece together her early personal and professional life. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The first chapter, "Designing for Art and Commerce," starts with an exploration of the collaboration between Tiffany and Driscoll, emphasizing their shared passion for nature and their preference for using photographs to study flowers and plants. The text continues with an overview first of the leaded-glass windows and then of the other objects that Driscoll and the "Tiffany Girls" designed. Step-by-step descriptions of the production of the windows, lamps, and other works, quoted directly from Driscoll's letters, significantly add to the brief discussions on the wall labels in the exhibition. Moreover, the treatment of the various objects is more balanced than in the show, which was dominated by the lamps. In their analyses of production methods, the authors stress the significance of the Women's Glass Cutting Department, stating that in the case of the windows, the methods of production may not be that innovative but "the active participation of women in the work was novel," and the male and female work forces were "essentially interchangeable" (pp. 30, 34). As revealed by one of Driscoll's letters, she sometimes had to take on the tasks of the men: "You ought to see me with sleeves rolled up doing plaster work with a trowel [to solidify a mosaic]. It is really great fun" (p. 41). The importance of the women's department is further underscored by repeated claims that the women undertook major commissions, several of which are mentioned – the rose window for the chapel at the World's Columbian Exposition and the mosaic friezes for Wade Memorial Chapel, Lake View Cemetery, Cleveland, Ohio. The section of the chapter on lampshades credits Driscoll with their design but elaborates on the collaborative nature of the work, noted repeatedly by Driscoll herself. It also addresses some of the practical concerns that dictated the manufacturing of lamps, Driscoll's eventual standardization of production to reduce costs and generate more sales, and the special orders with which she had to contend. The chapter concludes with a short account of her modeling of designs for fancy goods, the work in pottery and enamelware done in the small women's workshop in Corona, Queens, and an analysis of her scheme, "the Ideal Future," a handicraft cooperative inspired by the Arts and Crafts Movement that she longed to establish in her home town of Tallmadge, Ohio. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Switching from Driscoll's role as designer to that of manager, the second chapter, "Managing at Tiffany Studios" highlights her skills as a middle manager and her ability to negotiate "the bureaucratic and interpersonal complexities of Tiffany Studios" (p. 98). The topics addressed are largely dictated by the contents of her letters. Highlights include her comments on the comings and goings of her employees and the quality of their work and their marriages, her frustration with the new contract system that required complex bookkeeping, the competition between the men's and women's departments, and her interactions with the directors of the company, "the Powers that Be." | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The final chapter elaborates on Driscoll's social life outside of Tiffany Studios and the conditions faced by a turn-of-the-twentieth-century working woman in New York City. It addresses her boardinghouse life; her circle of friends, including several young artists; the retail stores where she shopped; the performances she attended; her collaboration with other pioneering women, most notably the American dancer Loie Fuller for whom Driscoll designed three little screens for one of her performances, and the photographer Gertrude Käsebier who took her portrait; and her engagement with politics, despite the fact that women were unable to vote. Although the catalogue provides a fascinating account of Driscoll's personal and professional life and the inner workings of Tiffany Studios, this information often is presented at the expense of close analysis of the objects themselves. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Contribution These two exhibitions, together with another Tiffany show, Distinctive Desk Sets: Useful Ornament from Tiffany Studios, which ran concurrently at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, demonstrate the continuing and increasingly widespread interest in Tiffany and Tiffany Studios. In general, it can be argued that both exhibitions under review here contributed to an understanding of Tiffany as an artist and to the growing field of "Tiffany studies." The Metropolitan Museum of Art's show focused on Laurelton Hall for the first time and revealed that this dream home was a monument into which Tiffany poured a considerable amount of his artistry and personal history. To the show's credit, it detailed Tiffany's collecting and extensively researched all the objects that once resided at his estate. Although I felt the research culminated in more reportage than analysis, the material itself made up for the loss of interpretation. Yet, after seeing the exhibition, I questioned whether it was worth reconstructing the highlights of Laurelton Hall. Would it have been better to showcase only the objects and to have left the reconstruction to a film or a digital presentation that toured the audience through the house? A New Light on Tiffany, inspired and framed by Clara Driscoll's letters, did offer a new perspective on Tiffany about the extensive role played by his employees in the success of his business. Unlike Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall, it took aim at the, admittedly all too easy, artist–genius designation, often adopted in discussions of Tiffany. Instead, this presentation of Tiffany emphasized the highly collaborative aspect of the design and fabrication of some of his finest works, namely the lamps. And surprisingly, his collaborators included lively and savvy women, characters as complex as Tiffany himself. Certainly, both exhibitions broke new ground and were serious, carefully prepared shows yet their methodologies were opposing. Louis C. Tiffany and Laurelton Hall continued the adulatory writing about Tiffany, begun in Robert Koch's groundbreaking study Louis C. Tiffany: Rebel in Glass (1964), while A New Light on Tiffany furthered the more critical investigation of the contributions of Tiffany's staff, initiated by Martin Eidelberg and Nancy A. McClelland in their work on Arthur J. Nash, the head of Tiffany's glassworks.5 All approaches have their virtues and vices, but it is rare to find two shows in such close proximity that exemplify distinct ways of building the Tiffany enterprise. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isabel L. Taube School of Visual Arts, New York isabeltaube[at]hotmail.com |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related links: The Metropolitan Musuem of Art Special Exhibits site: Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall—An Artist's Country |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

I wish to thank Gabe Weisberg for his insightful comments as well as Mary Flanagan in the Communications Department at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Laura Washington, Vice President of Communications at The New-York Historical Society, for their assistance in obtaining photographs of the installations and the objects. 1. Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, "Introduction" in Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall—An Artist's Country Estate. Ex. cat. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2006), 7. This page number and all succeeding page numbers for this catalogue (hereafter cited parenthetically in the text) refer to the hardcover edition. 2. Linda S. Ferber, "Foreword from the Director" in A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls. Ex. cat. (New York: New-York Historical Society in association with GILES, London, 2007), 9. This page number and all succeeding page numbers for this catalogue (hereafter cited parenthetically in the text) refer to the paperback edition. 3. Not until after I read the catalogue and attended the Sunday at the MET lectures given by Frelinghuysen and the architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson did I fully comprehend the layout of Laurelton Hall and its embodiment of Tiffany's personal aesthetic vision. 4. The educational programming that accompanied the exhibition included two Sunday at the MET events. At the first one, The Beggar Maid was shown with a live piano accompaniment. 5. Robert Koch, Louis C. Tiffany, Rebel in Glass (New York: Crown Publishers, 1964); Martin Eidelberg and Nancy A. McClelland, Behind the Scenes of Tiffany Glass-making: The Nash Notebooks (New York and London: Saint Martin's Press, 2001).

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||