The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

What's in a Name? Artist-Run Exhibition Societies and the Branding of Modern Art in Fin-de-Siècle Europe |

|||||

| In the decades framing the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, artists throughout Europe formed an unprecedented number of large and small, formal and informal groups and exhibition societies. The most prominent of these—the French Société des Artistes Indépendants (1884), British New English Art Club (1886), Munich (1892), Vienna (1897), and Berlin (1898) secessions, Belgian Les XX (1883), Czech Mánes (1887), Polish Sztuka (1897), Bulgarian Rodno Izkustwo (1893), and Danish Frie Udstiling (1891)—not only occupied key positions within the complex system of the European art economy (operating in and across its local, regional, and transcontinental strata), they were largely responsible for creating and sustaining public awareness of Modern Art as a new, distinct, and superior form of contemporary art practice.1 | ||||||

| If one were to look beyond the core years of the fin-de-siècle, and expand the period under consideration to include at the beginning the Belgian Société Libre des Beaux-Arts (1868) and the Impressionists (1874) and at the end the explosion of Expressionist, Cubist, Futurist, Constructivist, and Dadaist groups, the sheer scale of the group phenomenon and its coincidence with the emergence of modernism as a significant market force gives one a pause.2 Yet, despite the prevalence of artist-run exhibition societies, and their high visibility and profound local and often continental impact, the majority of art historic accounts of the period have failed to consider individual exhibition societies as manifestations of a general trend towards incorporation of individual artists within groups. If Thomas Kuhn is correct in his description of paradigms as horizons delimiting the universe of relevant problems for a particular field, then this failure of recognition is likely a result of the paradigm-driven assumptions which have determined not only the narrative focus of classical art history, but also its deeply engrained aversion to thinking about Art as an outcome of professional practice.3 | ||||||

| Instead of considering exhibition societies as corporate, or collective agents representing interests of individual artists forced to contend with an increasingly complex and competitive environment, art historians have been consigning them to the institutional background of the story of (Modern) Art.4 Needless to say, those groups associated with canonical figures or assigned a major role within that narrative have fared better than others. Linguistic and physical accessibility of archival material also has had a profound impact on research, awareness and perception of particular societies. The vast literature on the Impressionists, and the significant body of scholarship on the German and Austrian secessions and the Belgian Les XX, stand here in stark contrast to the scarcity of information in the major languages of art history on East European, South European, and Scandinavian societies.5 | ||||||

| The main problem facing anyone wishing to undertake a broader comparative study of group dynamics is that much of the basic information concerning what, when, where, and how is scattered across the linguistic terrain of Europe or simply unavailable. For every prominent, large-scale organization located in a major European art center that has been studied, there are scores of smaller societies that were active in art-historically peripheral areas, and consequently have not registered on the mainstream's disciplinary radar.6 Also, art history has lagged behind other disciplines in developing tools and methodologies for comparative analysis of complex socio-economic phenomena and for mapping of other than stylistic trends. | ||||||

| Most significantly, because group dynamics are by no means confined to the art economy, if art history were to systematically address the problem of art groups, it could emerge as major contributor of theoretical models for a broad range of disciplines from economics and political science to psychology and sociology. As desirable as that may be, we currently lack reliable data that could form a basis for a systemic comparative analysis. We have no typology that could allow us to begin mapping or even recognizing similarities and differences between groups; no internal theoretical frameworks for considering the mechanics and dynamics of group behavior; no models for analyzing structures of leadership or affiliation, groups' interactions with cultural policies and with various support structures (local and international media, institutions, exhibition venues, governmental agencies, etc.), or, for that matter, their relationship to ideology and discourse, including the discourse of art history. The basic research is simply not there, much less the kind of meta-analysis needed to begin answering even the simplest systemic questions. | ||||||

| What is certain, however, is that the artist-run exhibition societies played a key role in shaping the cultural landscape of fin-de-siècle Europe.7 The majority, especially in Central and Northern Europe, enjoyed high visibility, prestige, and official recognition, and received significant financial support from both public and private sources. Although individual societies differed in details of organization, longevity, focus, and continental prominence, most were committed to a particular type of contemporary practice. They tended to promote what became known as Modern Art, an umbrella term covering a broad spectrum of stylistic tendencies and approaches, which in retrospect may seem unified only in their rhetorical opposition to the traditional "academic" practice. They were also keenly aware of the workings of their local and regional art economies, skilled at taking advantage of various opportunities, and conscious of their position within the continental art system, international and domestic markets, and institutional and governmental power structures.8 | ||||||

| Their mass appearance on the European art scene within a fairly compressed period of time raises the question of what conditions prompted artists all over Europe to form collectives? Why were those associated with modernism more likely to form new societies than their more conservative colleagues? What were the advantages of a group membership? And finally, how were the artist-run exhibition groups involved not only in the spread of modernism, but in its rapid ascent to a dominant position within the European art system and in the emerging global market for contemporary art?9 | ||||||

| In beginning to address those questions, this essay departs significantly from the traditional methodologies of classical art history. It looks to economic and business theory used in analysis of market behavior of corporate entities, understood as producers of goods as well as discourses, in order to consider artist-run exhibition societies as agents representing collective interests of artists and functioning as such within an increasingly competitive and crowded market of art options and ideas.10 In particular, it focuses on one aspect of the corporate behavior, namely the use of branding as a market strategy.11 | ||||||

| The Art of Branding In the simplest terms, brands differentiate products from a field of generic goods or commodities.12 According to Jonathan Knowles, they "allow us to perceive important differences between things that, from a functional perspective, are more or less identical."13 We can all think of many examples that apply here: Pepsi versus store brand cola, generic aspirin versus Bayer. In certain cases, it is very difficult indeed to see a difference between a generic and a brand name item, yet both find buyers in a marketplace despite significant differences in price.14 Why do consumers opt for the more expensive brand names? According to market research, brands appeal to us on an emotional level. They create associations and relationships based on perceptions and expectations. These subtle and not-so-subtle distinctions perceived by consumers between brand name products and generic goods, many of which are created and reinforced by targeted marketing, advertising, and packaging, are key to positioning a brand within a marketplace. Brands communicate particular meanings related to social, cultural, and economic identity and status sought or desired by consumers. Paradoxically, in endowing a product with other than strictly functional value, they rhetorically "de-commodify" it, much in a way that an exhibition of art at a venue that explicitly rejects commodification as a market evil (all the modernist artist-run exhibition societies fall in this category), implicitly suggests that the works offered for viewing and sale are beyond the scope of a "base" market considerations.15 The recourse to brand marketing theory illuminates, therefore, among other things, the logic behind the exhibition societies' rhetorical disavowal of commercialism which occurred simultaneously with their refinement of commercial practices which included, in many instances, close collaborations with dealers and galleries. |

||||||

| While considering the brand analogy, we must keep in mind that the perception of inherent superiority of certain brand name products is not simply a result of effective marketing. It is often based on significant qualitative differences. According to Paul Duguid, branding as a commercial marketing strategy first developed in the early 19th century in response to the widespread practice of adulterating alcohol products. The custom of "improving" wine and spirits by mixing cheaper and more expensive products or adding suspect ingredients created market conditions that favored firms with established reputations. The name of the established firm served in this environment as a warrant of reliability, purity, and ultimately superiority of the branded product.16 The consumer perception of the superiority of the brand name has been the foundation of branding as a market strategy ever since. In this context, producers' commitment to quality—to be the best, the purest, the fastest, the safest, the most reliable— no matter how it is explained by the company's advertising, is never disinterested. It is always motivated by a desire to secure, maintain, and increase market share and profit. It is crucial for ensuring consumer satisfaction and building brand loyalty. Ultimately, within a competitive environment, it is essential for the company's long-term survival and growth.17 | ||||||

| This does not mean that branding of cultural products such as art works operates with exactly the same logic and aims as does branding of ordinary consumer goods. Nor do I wish to suggest that there is no difference between a painting and a bottle of port. Of course there is. However, as James Twitchell has pointed out, branding understood as a "commercial process of storytelling" applies not just to commercial enterprises, but also to corporate entities ostensibly engaged in non-commercial activities, such as churches, museums, or universities.18 I would add to this list artist-run exhibition societies. In the context of such institutions, branding often relies on specific ideological references to narratives about the superiority and uniqueness of particular ideas promoted by the organization. That form of branding does not operate within the commercial sphere of consumer goods; it functions within what Pierre Bourdieu identified as the markets of cultural capital and what I am referring to as the art economy.19 Here, art economy refers to the entire spectrum of production, distribution, reception, and consumption of art works, and to reputations as well as art ideas (conceptual or visual). It is, therefore, not just a sphere of commercial transactions; it encompasses the totality of the social, discursive, and market structures and interactions that play a role in conferring and negotiating value (economic as well as symbolic) within a particular art system. | ||||||

| It is also important to keep in mind that branding is not just a marketing tactic. It is a market strategy aimed at securing and expanding the market share and therefore long term viability of the firm that brings the branded product to the market. In cultural markets, the market share impacts and reflects status, authority and dominance, not simply earned income and profit. Maintaining this distinction, the theory of branding allows us to identify and place specific patterns of corporate behavior of the fin-de-siècle artist-run exhibition societies: their efforts to differentiate works exhibited in the context of their exhibitions from the rest of the art field, to frame those works as Modern Art, to identify Modern Art as a qualitatively distinct and superior form of contemporary art, and finally to make Modern Art synonymous with Art as such by defining quality in terms of their own practice. It also accounts for practices such as targeted marketing, which tended to maintain and reinforce pre-existing cultural distinctions between the philistine public and the cultural elite, and reliance on visual promotion strategies (posters, logos, logotypes, architecturally distinct venues, publications, and aesthetically choreographed presentations of artworks) that encouraged particular perceptions of the groups and consequently of the works they exhibited.20 | ||||||

| The recourse to branding as a theoretical model for understanding the behavior of the exhibition groups is also entirely appropriate from a historical perspective. The emergence of the artist-run exhibition societies as key market agents in the final quarter of the nineteenth century coincided with the advent of modern mass-marketing techniques. During this period, branding as a general market strategy began to be used by European and American firms responding to the changing economic and market conditions. The increasing prominence of large-scale producers and distributors, growing middle class demand for new products and new experiences, mass production, internationalization of trade, growing competition, development of efficient transportation networks with a continental and inter-continental reach, rapid growth of mass media, and development of improved commercial color printing technologies created an environment within which firms were able, for the first time, to take full advantage of branding not only in the marketing of individual products, but of their entire product lines. Many of the most familiar and distinct brand names, Michelin, Kodak, Gillette, Siemens, Rolls-Royce, had their beginnings in this period. One of the principal innovations of the 1890s was the development of corporate identities through trademarks, logos, themes, symbols, and anthropomorphic characters such as Bibendum, the famous Michelin Man, introduced in 1898.21 | ||||||

| The marketing methods used by the large firms were copied on the local level by small producers who, in their efforts to promote their products, frequently called on local artists to create visually compelling advertisements, packaging, and displays. Not coincidentally, members of the various societies were frequently involved in the production of posters and ads for commercial clients at the same time that they were designing promotional materials for their own societies, with the logic and design strategies used in both instances sharing not only a similar aesthetic but also similar assumptions and goals. | ||||||

| The Association of Polish Artists "Sztuka" The convergence between modern marketing techniques and the marketing of Modern Art in the context of the fin-de-siècle exhibition societies is too broad a topic to address adequately here. Instead, I will focus my analysis on a case study of a single exhibition society, the Association of Polish Artists "Sztuka," founded in 1897 in Krakow, which employed a number of strategies that were commonly used by the fin-de-siècle artist-run exhibition societies, especially those operating in Central and Eastern Europe. |

||||||

| Although Sztuka was ostensibly dedicated to the promotion of what it considered to be the best Polish contemporary art, it was in practice a preserve of broadly defined modernism. Modeled on the Munich and the Vienna secessions, Sztuka's members adapted their group's organization and priorities to the local conditions. What distinguished Sztuka from its Western counterparts was the unprecedented speed with which it succeeded in consolidating its position. Even though from the outset both the Munich and the Vienna secessions received official support and were eminently successful, they had to contend with preexisting power structures of the local artworld and bureaucratic hierarchy. Operating under unusual conditions resulting from Poland's partition, in a cultural environment that, for all practical purposes, was devoid of a unifying institutional or state authority, the artists of Sztuka took advantage of what was in effect a power vacuum. They had no competition since they were the first artist-run exhibition society to enter the Polish art world centered in Krakow. Within less than three years, they achieved the remarkable feat of not only gaining mainstream status, but becoming the dominant force in the Polish speaking artworld and establishing a de facto monopoly on official exhibition of Polish contemporary art beyond the borders of former Poland.22 | ||||||

| As a result of Sztuka's activities, by 1900 Modern Art was treated by the local Polish and the Hapsburg authorities as the official national style. Art that was not Modern, or existed outside Sztuka's sphere of influence, gradually ceased to be considered in serious discussions. In other words, the success of Sztuka was synonymous with the success of modernism in so far as Sztuka's members used the exhibition society to establish the criteria for evaluation of quality and art historic significance of contemporary art. Their own practice, presented as Modern Art, functioned in this context as the standard of excellence and was used to devalue works by artists who were not and would never be invited to join. | ||||||

| How are we to explain Sztuka's rapid rise to a dominant position within the Polish speaking artworld? Was it a result of a happy coincidence, of being at right place at the right time? Was it simply due to the superiority of works promoted by the society, or did the leadership and members of the society ensure this outcome through their collective actions and decisions? If so, what specific strategies did they use? In raising those questions, I am not suggesting that the Polish artists were solely motivated by commercial considerations, though, as we will see, they were certainly interested in achieving economic success. They were quite idealistic in their perception of their mission and their attitudes towards art. At the same time, they were professional artists in mid-careers; they aspired to a middle class lifestyle and had family obligations. The majority supported themselves by selling works, accepting commissions, and teaching. Given these circumstances, it is difficult to imagine that they did not know their own professional environment, were ignorant of the ways in which it functioned, or did not know how to affect their personal standing within the hierarchies of the local and regional markets and government bureaucracies. This is not to say that all members of the group were equally good at self-promotion, self-positioning, and production of work that garnered attention and respect. However, on average, they made decisions and acted in a manner that ensured their individual and collective good fortunes. The goal of this essay is to postulate a hypothesis regarding that professional success, which translated almost immediately into canonical status within Polish art history,23 and to offer a new way of approaching the subject of artists' groups (those that came into prominence at the fin-de-siècle and those that have been forming ever since) with an aim of proposing an alternative reading of the history of modern European art, one that is not predicated on a narrative structured by modernist assumptions. | ||||||

| The Founding of Sztuka: Myths and Realities The circumstances that led to the founding of Sztuka have been frequently recounted in the literature on Polish nineteenth century art. The basic chronology and descriptions of what happened has varied remarkably little over time. The standard art historic account of the society's early years is a narrative of modern Polish art asserting its independence and striving (in vain, according to some commentators) to gain external recognition. It operates within a framework of a familiar modernist plot: the progressive artists making a courageous stance for quality in the face of all-pervasive mediocrity, succeeding against all odds, and triumphing in the end, having survived the "test of time." The remarkable consistency of the accounts obscures, however, the fact that the information on which they are all based comes from only a handful of sources, most of which can be traced directly to Sztuka. The problem is compounded by the fact that the contemporary press coverage of the various events did not offer an independent perspective; it often simply repeated the society's public pronouncements24 |

||||||

| Two texts loom large within this discourse: a one page report published by Sztuka's executive committee in 1899 in the Warsaw journal Illustrated Weekly, and a commemorative album produced by the society on the occasion of its 25th anniversary in 1922.25 The accounts presented in these two documents offer different interpretations of the events, a fact that has been generally overlooked by the secondary literature. The 1922 album, which is full of factual errors and inconsistencies, relates that the idea to form an exhibition society originated among Polish artists studying in Paris in the early 1890s. In particular, it identifies painters Józef Chełmoński (elected in absentia as the society's first president) and Jan Stanisławski (the society's president from 1899 to 1906) as its main champions.26 | ||||||

|

However, the 1899 report, co-authored by Stanisławski, Teodor Axentowicz and Józef Mehoffer, all members of Sztuka's executive committee, makes no such assertion. It gives no special credit either to Chełmoński or Stanisławski nor does it trace the pre-history of Sztuka beyond 1897. It simply states that in the winter of that year "a group of Kraków artists" began to plan a "separate exhibition of paintings and sculptures." It also informs us that these plans resulted in a show, which opened on May 27, 1897 in the rooms of the Krakow Society of the Friends of Fine Arts (at the time the city's only exhibition venue showing contemporary art) at the former town Cloth Hall (Sukiennince), a location which also housed the National Museum (fig. 1).27 The show lasted one month and included sixty-seven works by seventeen artists.28 The authors of the report observed that despite a separate admission charge, the exhibition was visited by approximately six thousand viewers, a significant number for provincial Krakow which in 1900 had a population of approximately 85,000.29 The artists observed with evident satisfaction: "The outcome exceeded expectations. The public came in droves, expressions of appreciation and encouragement were not spared, and the number of buyers was unusually high."30 | |||||

| The same report notes that in the fall of the same year (1897) the group organized a second show, this time in Lvov, the provincial administrative center, and that on October 27 it held its first organizational meeting.31 Fifteen artists who participated in that gathering formally adopted the name Association of Polish Artists "Sztuka," approved a charter, drew up a set of bylaws, and elected an executive committee.32 We also know from an unpublished letter written by Mehoffer to his wife, that the newly founded society planned to register with the Austrian government, a move which would have given it an official status and entitle it to financial subsidies.33 The 1922 anniversary album confirms this information, noting in several places that Sztuka received financial support from the Austrian government and was repeatedly approached by the Ministry of Culture to represent Polish artists at various international expositions. This information is confirmed by the society's exhibition record, its minutes and by contemporary press coverage. | ||||||

| On close examination, this seemingly straightforward sequence of events, which has been repeated without closer scrutiny by the subsequent art historic accounts of the period, reveals several interesting inconsistencies. For instance, the traditional designation of the May 1897 show as Sztuka's first public appearance (a designation based on the society's consistent citing of the exhibition as its first show) has not been questioned, despite the fact that it could not possibly be correct. After all, the society did not yet exist in May. Moreover, despite significant overlaps, not all artists who participated in the May show went on in October to form Sztuka. Of the seventeen artists in the May show, twelve participated in the meeting that formally founded the society and only eight (together with 2 artists who had not been in that show) became founding members. Four artists who took part in the May show chose not to join the newly created exhibition society.34 | ||||||

| Much the same can be said concerning the officially given reasons for Sztuka's founding. In this regard historians have tended to rely on the society's explanations, especially the later ones. The authors of the 1899 report noted, for instance, that the organizers of the May 1897 show were driven by a desire to create an exhibition that would surpass the level of artistic achievement of what they refer to as an "average" show at the Krakow Society of Friends of Fine Arts, the local Kunstverien. The questions of why that became so important at that particular time and what else the artists may have wished to accomplish, beyond their stated reason, have not been raised. | ||||||

|

By 1922, the rather modest goal of hosting a "better exhibition" acquired a much more heroic dimension, reflecting Sztuka's self-perception and status as the oldest, the most prominent, and also, by this time, one of the most conservative Polish exhibition societies. In an overview of Sztuka's history published in the commemorative album, Franciszek Klein describes the May show as a "noble protest" against the low standards prevalent at the Society of the Friends of Fine Arts.35 Another essay, by Tadeusz Żuk Skarszewski, which appeared in the album in Polish, as well as French and English translations, identified all of the society's actions with patriotic and selfless pursuit of the highest artistic standards. Skarszewski wrote:

The image of Sztuka that emerges from this and other similar statements, and which has been perpetuated by the secondary literature, is indeed heroic. The society is portrayed as a champion of quality and its members are identified, without qualification or question, as the best Polish artists of the period. Their actions are ascribed in equal measure to idealistic pursuit of pure art and deeply felt patriotism. Professional interests are almost never mentioned and when they appear they are generally introduced parenthetically and without further commentary.37 What seems at stake, in the end, is not the artists' individual or collective success, but the very survival of Polish culture under the conditions of foreign occupation. |

||||||

| Although I do not wish to negate those motives, I would like to suggest that they present a highly problematic reading of the historic record. Despite our reticence to view modernist exhibition societies such as Sztuka as professional organizations advancing financial as well as ideological interests of the members, we must do so. The 1899 report produced by Sztuka clearly indicates that the society's leadership cared whether it was operating with a surplus or a deficit. The minutes of the society's meetings for the period 1898–1912 consistently reflect the leadership's interest in financial issues. The published charter and the unpublished bylaws likewise stipulate in considerable detail financial arrangements and provisions of the organization, as well as the financial stakes of the members in profits resulting from exhibitions.38 It is also important to note that group's effectiveness was perceived in those terms by contemporary commentators. For instance, writing in 1904, Antoni Potocki, a correspondent for the Paris-based Polish journal Art observed, with much evident pride in Polish artists' accomplishments, that Sztuka succeeded in making for itself a brand name [firmowe nazwisko] abroad.39 | ||||||

| If we re-examine the first years of the society's existence, paying attention not only to the sequence of events but also to the implications of the specific actions taken by the group, we have to acknowledge the accuracy of Potocki's observation insofar as there is a clear pattern of behavior entirely consistent with a successful branding effort. Within that pattern, the initial May show played a key role. It demonstrated the effectiveness of differentiation as a market strategy and allowed the artists to test some of the marketing ideas that they later refined. At the time of the May show, all the elements eventually used by Sztuka in self-promotion were already in place. The artists staged a physically separate show (with a separate admission charge) at the city's main exhibition venue,40 they published a poster and a catalogue, and developed a logo. As we will see, they also chose a word that identified them, even though they did not formally adopt it as a group name. In short, they clearly understood the basic precept of marketing, namely that having a good product is not enough. To be successful, one must differentiate oneself from the competition and advertise the existence of that difference. | ||||||

| The fact that the May show became known only retrospectively as Sztuka's "first show" is significant in this context because it reveals that the decision to officially form an exhibition society was likely motivated by the success of the May exhibition. If that were not the case, then the artists would have formed the society before putting on the show—clearly a much more effective approach. The fact that they did not, suggests that only afterwards did the core group of artists became convinced of the concrete advantages offered by a distinct group identity. The May show not only gave them instant visibility (6,000 visitors saw their work) and recognition (favorable and encouraging responses), but also allowed them to reap tangible economic benefits (the sales exceeded their expectations). The report does not elaborate any further on the financial gains reaped by the participants. However, the sales records published by the Society of the Friends of Fine Arts for 1897 reveal that the May show accounted for over fifty percent of the society's total sales of contemporary art to private patrons for the entire year.41 This outcome not only "exceeded the expectations;" it most likely demonstrated to many of those involved the value of the group strategy. It is no wonder that the majority of the artists involved in the project wished to continue and formalize their affiliation. | ||||||

| They did so following a well-established precedent. By the 1890s, officially registered artists' associations were a common feature of the Central European art scene. There were also, by that time, a number of modernist exhibition societies active throughout Europe. In the immediate regional neighborhood, Polish artists could look for a model to the Munich Secession, founded five years earlier in 1892, and to the Vienna Secession, founded just few months before Sztuka, both extremely successful and visible locally and regionally.42 | ||||||

| The artists who formed Sztuka were very familiar with both societies. Just two months prior to the May show, in March 1897, the Krakow Society of the Friends of Fine Arts, organized an exhibition of the Munich Secession, which was favorably reviewed by the local press.43 Although we do not have any extant statements that record how the Polish artists responded to the show, it is likely that the exhibition by German artists must have spurred discussions and likely mobilized them to action. Their awareness of and involvement with the Vienna Secession was even more direct. Julian Fałat, the recently appointed director of the Krakow School of Fine Arts, one of the participants in the May show and a founding member of Sztuka, became one of the founding members of the Vienna Secession in May 1897. By the end of 1897, nine other artists of Sztuka, all Austrian citizens, joined the Austrian exhibition society as regular members.44 | ||||||

| In view of those circumstances, it is unlikely that the founding of Sztuka was simply a heroic stand for quality, motivated only by selfless idealism and patriotic fervor. Rather, it should be viewed as part and parcel of the modernist artists' collective effort to consolidate their position within Krakow, the extended Polish speaking artworld, and in the region of Central Europe. This is particularly so since the core leadership of the society consisted of the newly hired faculty of the Krakow School of Fine Arts. In fact, the school functioned as the unofficial headquarters of the society and was often the site of the executive committee and general membership meetings. Julian Fałat, shortly after his appointment as the school's director in 1895, began to take concrete steps to modernize the curriculum and raise the institution's profile within the Austrian cultural bureaucracy. Due to his efforts, of which the formation of Sztuka was a key component, in 1900 the government conferred on the Krakow school the rank of an Art Academy, a legislative and therefore political decision that carried with it a considerable increase in available resources, including the amount of funds dedicated to faculty and administrative salaries. | ||||||

| There were other reasons why forming a group made a great deal of sense. By the mid 1890s, artist-run exhibition societies functioned in the region of Central Europe as collective agents, showcasing and discursively framing works by individual artists. They not only staged shows of members but, as we have seen with the example of the Munich Secession, organized touring exhibitions. Most importantly, groups formed relationships and made exchanges with one another and were frequently approached by operators of major venues to organize shows.45 They were also called upon by governments to represent the nation's (or ethnic group's) artists at rapidly proliferating international art exhibitions and fairs. Their power rested in their visibility and the ease with which other groups, organizers of international events and local governments could approach them, as opposed to the individual artists who were their members. They were also much easier to work with since they provided the organizational infrastructure that otherwise would have to have been provided by the host venues. | ||||||

| Groups had another advantage over unaffiliated individuals. While individual artists could certainly join various societies or receive invitations to participate in particular shows, their negotiating power vis a vis the host organization was necessarily limited. On the other hand, collaborations between groups created a radically different power dynamic, which not only allowed much more readily for recognition of distinct national identities, a key concern at the fin-de-siècle, but also gave groups a significant advantage in negotiation of financial arrangements and terms.46 | ||||||

| What's In a Name? Marketing experts agree that the strongest brands are the most distinctive. The ability to differentiate a product from a field of competitors can be achieved through product design, packaging, advertising, and various promotion strategies. In this context, brand names acquire significant value. They are tangible corporate assets, a fact that is clearly recognized by the protection they are accorded under trademark and copyright laws. The consumers' ability to recall a particular brand name, an important factor in building brand loyalty, is as much a result of consumer satisfaction and desire for repeated experience, as of effective advertising. The association of a product with a particular name—in other words, the creation of a distinct brand identity—is in all cases a result of conscious corporate strategy. The name becomes identified with particular qualities and values that cover not only individual products, but entire product lines and the corporate entities that produce or market them. |

||||||

| The importance of the right name was not lost on the Polish artists. Sztuka's official name, Association of Polish Artists "Sztuka," chosen at the October meeting, immediately began appearing in the press in an abbreviated form as Sztuka. It signaled the society's elitist and idealistic commitment to a particular agenda (even if this agenda was never unambiguously articulated in the form of a manifesto) as Sztuka is, simply, the Polish word for Art. | ||||||

| Although the group that organized the May show did not identify itself formally as a named society, it did produce a poster and a catalogue that carried a logo bearing the Latin term Ars or Art (fig. 2). Designed by Axentowicz, one of the founding members of Sztuka, the logo resembled, in its basic design logic, the emblem of the Munich Secession designed in 1895 by Franz Scarbina (fig. 3). The 1899 report notes that Sztuka adopted the Ars logo in October as its emblem. It appeared on the catalogue cover for Sztuka's 1898 Krakow show—the first exhibit organized by the society in its home town after its official founding and naming— but, curiously, it was never used by the society afterwards. | ||||||

| Why was the original logo so quickly abandoned? If we accept the argument that Sztuka was attempting in this period to forge for itself strong name recognition and a distinct group identity, then its decision to abandon the Ars logo is fully consistent with this goal. Even though both Ars (Latin) and Sztuka (Polish) mean Art, the word Ars was never the society's proper name. As the society, from its inception, was referred to in the press by the abbreviated form Sztuka, it is likely that the decision to abandon the original logo was motivated by a desire to avoid the confusion that could have resulted from the circulation of two different names. | ||||||

| The more difficult question to answer is why the society adopted the Polish term instead of the Latin one, especially if the latter was already in use, it would have been immediately understood abroad, and was much easier to pronounce by foreigners? If we accept the premise advanced by Jan Cavanaugh that the Polish artists were on the "outside" of the international art scene "looking in," trying, in other words, to participate in fashioning international modernism, this strategy makes little sense.47 Cavanaugh asserts that despite their efforts and professed ambitions, the Polish artists never achieved international recognition or entered the history of European modernism. She attributes this to the methodological prejudices of art history, namely its prioritization of French modernist avant-gardism. The image that emerges from her account is one of artists working in an area geographically distant from the acknowledged art centers, whose work, despite its superior quality, never received the critical recognition that it deserved. | ||||||

| While it is certainly true that Polish modern art and the artists of Sztuka are not well known outside of Poland, this may not be entirely due to the Western bias. The desire to see Polish artists as "outsiders" denied insider status by the Western European artworld and subsequent art historic narration of the period ignores the fact that Sztuka never made a serious effort to enter the international European art market centered in Paris. As much as it seems tempting to fall back on the grand narrative of European modernism, in which Polish artists clearly have not figured and to argue that they should be recognized and integrated into the expanding canon, I would like to suggest that it is much more productive to question the logic of the canonical designations by dispensing with the cohesive concept of modernism and to examine the situation from the perspective of professional advantages and disadvantages of particular strategies and decisions. | ||||||

| On this pragmatic level of historic analysis, the Polish artists' decision to abandon the cosmopolitan Ars in favor of the ethnically marked Sztuka points to a definite focus on the local (Krakow and Polish) and on the regional (Central European/Habsburg Empire), rather than the European/International art scene. It is worth noting that Sztuka's often-cited first exhibition "abroad" in 1902 took place in Vienna, a capital of the Hapsburg monarchy to which Galicja, the Polish province where Krakow was located, belonged. The show, hosted by the Vienna Secession, could only be viewed as happening "abroad" if one completely ignored the reality of Poland's partition, the administrative integration of Galicja into the Hapsburg Empire, and the Polish artists' Austrian citizenship. Much the same could be said of the other major shows that have been repeatedly identified as evidence of the group's desire to present Polish art to the international art audiences. They all took place either on formerly Polish territories (in major Polish centers of the Prussian and Russian partitions), in the territories controlled by the Hapsburgs, or under the patronage and by explicit invitation of the Austrian government. To put it simply, Sztuka did not organize an independent show outside Polish territories or the Hapsburg sphere of influence before 1905, and thereafter confined its activities to regional activities. When it participated in international exhibitions, it did so only as a result of either Austrian sponsorship or external invitation.48 Moreover, it did not seek ties with European societies outside Central Europe, and, most significantly, evinced no interest in organizing an independent show in Paris, despite the fact that many of its prominent members were familiar with the Parisian art scene. | ||||||

| If the artists of Sztuka were not interested in entering in a serious way the international art market, what were they interested in doing? I would like to propose that they were mainly concerned with securing their position within their own local artworld, a position that was predicated on creating a distinct brand identity not only for Modern Art as such, but for their own work defined as Polish Modern Art. When considered in this context , the society's limited forays onto the international art scene should best viewed as being discursively directed back at the local audience. The exhibitions "abroad," especially those demonstrating official recognition and support by the Austrian government, were used at home as the evidence of the Polish artists' regional and international recognition and status. Whatever sales may have resulted from these shows were secondary in significance to the main project of building and consolidating prestige at home. | ||||||

| Viewed in that light, the term Sztuka had a double advantage of being understood to signify not just Art, but Polish Art. Ars, on the other hand, would have had no such ethnic-linguistic advantage. It would have sent a message inconsistent with the groups' aims. While it clearly announced an allegiance to a universal ideal of Art, Ars did nothing to locate the society's national origin and explicitly patriotic focus. Given that in 1897 Polish modernism was still perceived by many at home as a foreign import (note the defensive rhetoric of the 1922 album essay), the shift to a fully Polish name must be seen as an ingenious move aimed at forestalling criticism, as well as a genuinely patriotic gesture meant to clearly convey Sztuka's commitment to promoting national culture. | ||||||

|

What is particularly interesting is the fact that when the society organized shows outside of the Polish territories, it always retained the Polish term Sztuka, while allowing appropriate translation of the rest of its name. The practice began with the earlier- mentioned 1902 show at the Vienna Secession. Its catalogue lists, under the heading Saal III, "Vereinigung Polonischer Künstler 'Sztuka' in Krakau." The same pattern was maintained for signage as well as catalogues in all subsequent exhibitions abroad. For instance, in the photograph showing the entrance to the exhibit organized by Sztuka in London in 1906, under the auspices of the Royal Austrian Exhibition, we can see the Polish word Sztuka embedded in the English translation of the society's full name (fig. 4). | |||||

| If we consider the consistency with which the society used the Polish word to identify itself abroad, we have to conclude that this strategy must have offered particular advantages. Within the realm of consumer products, companies frequently adjust their naming strategy to suit different markets. Although they often retain the original name for foreign markets, they just as often change or translate the name to encourage favorable perception of the product. For the artists of Sztuka, it was clearly important to be identified as Polish artists whenever they exhibited abroad. Their use of the Polish name in conjunction with appropriate translation, which clearly identified the word as Polish, ensured this outcome. It drew attention to the fact that the society was not a German- or a Czech-Austrian group. It also located it for anyone who may have had a particular interest in Poland, including many prominent Polish émigrés. The so-called "Polish Cause," namely the fact that the country existed under what many considered a foreign occupation, attracted considerable sympathy among liberally minded members of the European public. It is clear from the press coverage that the popular perception of Poland as a heroic, suffering nation, a populist David fighting a triple tyrannical Goliath (Russia, Prussia, and Austria), did not hurt Sztuka's reception. If anything, it gave the society a special status and ensured a great deal of good will among politically liberal critics. | ||||||

| Art Versus Mere Painting Within the local, Polish artworld, the name Sztuka had an added advantage of making the society synonymous with Art itself. This identification was supported by various statements concerning the nature and function of art made by writers and critics sympathetic to modernism, such as Stanislaw Witkiewicz, Felix Jasieński, Zenon Przesmycki, Stanisław Przybyszewski, Kazimierz Tetmajer and others.49 Sztuka's skillful promotion of itself as the standard of quality translated almost immediately into higher prices, prestige, and commissions for individual members. A comparison to producers of high-end luxury goods seems unavoidable. I would like to propose that the name Sztuka functioned on the Polish art market at the fin-de-siècle in a similar manner that the name BMW functions today in the car market. Both brand names stand for a high standard, i.e., quality, but also command a premium price. For those who can afford it, they represent a "top of the line" product, i.e., one that is inherently desirable and valuable. |

||||||

| The name Sztuka communicated uncompromising commitment to quality. It functioned as a guarantee that the works shown at the society's exhibits were Art-works. Conversely, it also implied that the work of artists who were not invited to join or who did not show with the society was second rate or perhaps did not even deserve recognition as Art. | ||||||

| The society cultivated this public perception by taking concrete actions. In order to ensure "quality," Sztuka adopted a strict review process for membership. The new members could join only by invitation, which had to be approved by a majority vote. The potential members were frequently invited to participate in Sztuka exhibitions as guests, but only select guests were eventually invited to become members. Beginning in 1899, the society also adopted a jury system under which works submitted for exhibition by members had to be first approved by the entire membership. Although this system was never fully implemented, the fact that it was attempted demonstrates the extent of the society's commitment to its mission.50 | ||||||

|

Publicity materials produced by the society reinforced the associations between Sztuka and quality and therefore Art. The poster designed by Axentowicz for the society's first official Krakow show, in the spring of 1898, demonstrates a striking visual presentation of that idea (fig. 5). Unlike the May 1897 poster, which included a logo (fig. 2) but was comprised mainly of a list of participants, the 1898 poster was distinctly visual.51 Even though it was produced as an announcement for the exhibit, it provided virtually no useful information. It did not list the show's duration, where it was taking place, or identify the participating artists. Instead, it emphatically drew attention to the society's abbreviated name, which appeared prominently in the bottom register of the poster's field. | |||||

| The entire 1898 poster functioned, in effect, as a logo or a visual manifesto of the society's vision of itself. Rather than informing the public about the show, it announced the arrival of Sztuka and therefore of real Art. If we compare it with the earlier image adopted by Sztuka as its emblem, certain similarities become evident. Both designs combine word and image in a coherent and economic graphic form. In both cases, Axentowicz used a female figure, which becomes recognizable within the logic of the design as an allegorical personification of Art. In other words, the word and the image become interchangeable, representing the same concept, but in different modes. | ||||||

| The main difference between the 1897 Ars logo and the 1898 poster is that of boldness and scale. The 1898 poster's striking design and use of vivid color had no precedents in Poland. To produce it, Axentowicz used color lithography, the same process favored by many French and Central European designers. The technique allowed him to produce a print that combined impressive size (111 cm by 64.5 cm), with bold, emphatically sketch-like handling. In the poster, the diminutive and constrained profile head of the logo is transformed into a fin-de-siècle goddess, complete with a flowing mane of bright red-orange hair. She is depicted in a manner that emphasizes the touch of the artist's hand. The result is a figure that functions not only as an allegorical image, but also as a concrete demonstration of what Art meant for Sztuka. | ||||||

| In this respect, Axentowicz's poster has an indexical, rather than illustrative character. The schematic black lines that define the figure's hair convey an impression of a free hand drawing. Ultimately, naturalism is subordinated to an overtly expressive intent and stylistic art-coding: note, for instance, deliberate placement of the laurel wreath around the figure's face, and the red marks within the gray field, as well as around the upper left outline of the figure's head, that emphasize the immediacy of drawing. In the end, the image does not function as a visual allegory of the concept of Art (even though it can be read allegorically), but as a work of Modern Art. As such, it is presented as clearly deserving of recognition on a par with Axentowicz's other works, a point that was explicitly acknowledged by Sztuka. | ||||||

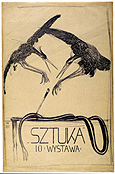

| In 1908, the print on which the 1898 poster was based was included in the applied arts section of Sztuka's show at the Viennese Hagenbund (fig. 6). We can see it prominently displayed, in the photograph of the installation, above a case full of various examples of graphic and book design. On the adjoining wall hangs another poster for a Sztuka show, this one designed by Wojciech Weiss, a student of the first generation of Sztuka's artists (fig. 7). It was created for the society's tenth exhibit in Krakow in 1906. Despite temporal distance of almost eight years, the logic initiated by Axentowicz in 1898 is also at work in the later poster. Here, too, the design aesthetic emphasizes the drawn quality and distinct art-coding. Moreover, the central image of two cranes hovering above a dead serpent pinned with a painter's brush recalls the stylistic signature of Weiss's "fine art" prints. The designer-artist makes no distinction in the handling of the Art-work and his graphic work; both are presented as belonging to the same aesthetic sphere. | ||||||

| In both Axentowicz's 1898 poster and Weiss's 1906 poster the name Sztuka not only identifies the society, but also the poster as a work of Art. By the late 1890s, the view that Modern Art was the only aesthetically and art-historically valid form of contemporary art practice was widely held among Polish progressive critics. It was certainly shared by the artists who formed Sztuka. Their participation in the May 1897 show was, after all, motivated by their negative assessment of the quality of works on display at the salon of the Krakow Society of the Friends of Fine Arts, a venue which, according to the modernist view, may have been full of paintings, but rarely featured works of Art. | ||||||

| The modernist assumptions used to determine quality, were ultimately used to define what was and was not worthy of the designation of Art. The distinction made during this period between a work of Art and a mere painting, or a work of craft—the former embodying absolute and transcendent values, the latter designating a particular skill-based practice—is therefore essential for the proper understanding of the society's name. A great painting was considered a work of Art, but not all paintings deserved such recognition. Many were simply hand made, more-or-less competent images. By the fin-de-siècle, not only in Poland but throughout Europe, this understanding of Art was widespread. Art had very little to do with manual rendering skill. It was a matter of conception and design. As such, it could not be taught, only encouraged. It was arrived at through personal dedication, experimentation, and continual practice. Innate talent and inspiration were also requisite. Painters who produced academically correct work demonstrated only command of a particular skill. They were considered by the modernists to be competent craftsmen, but they were not artists. Conversely, work that was not highly finished or "correct" by academic standards, but fit other expectations, could easily be included within the scope of Art. By this logic, a sketch, a print, or a work of graphic design could possess more merit than an academic canvas. | ||||||

|

Those distinctions were reinforced by the society's exhibition strategies, which presented not only paintings and sculptures but artist-designed decorative art objects as works deserving special aesthetic attention. Although the arrangement of the pieces in the May 1897 show followed the standards of the old manner of display (top to bottom filling of the available space), the subsequent exhibitions organized by Sztuka at home and "abroad" adopted modern(ist) exhibition practices favored by other artist-run exhibition groups (fig. 8). The society exhibited relatively few pieces, each displayed in the most advantageous manner possible. The arrangement of the shows stressed the overarching and unifying design aesthetic. It aimed to create a refined environment which encouraged prolonged contemplation of each of the works, no matter how small or conventional. The larger works were generally shown in a single row, at eye level; the smaller ones were often grouped in aesthetically pleasing arrangements. The color schemes of the walls and individually designed decorative motifs enhanced the sense of cohesion. Frequently specially designed and manufactured furniture completed the ensemble. Although the physical space of the exhibition was not yet the familiar modernism white cube, it functioned in a similar manner, creating a secular equivalent of a sacred space in which paintings, sculptures and applied art objects were packaged and coded as Art. | |||||

|

The 1899 report explicitly noted those aims. In outlining the goals of the society, it stated that the exhibitions should create a consistent and readily identifiable image of Sztuka as the champion of progressive contemporary art, i.e., of Modern Art:

This concern with preserving a particular image or "special character" demonstrates not only Sztuka's desire to encourage a particular perception of itself as the champion of progressive trends within contemporary art but also its awareness that such perception was something that had to be cultivated, actively shaped, and guarded against dilution. |

||||||

| The Dominant Brand By the first decade of the twentieth century, Sztuka, through its connection with the Krakow Academy of Fine Arts was, in effect, functioning as an academy. Its exhibitions were defining the standards for contemporary art practice and, thereby, shaping the perception and affecting the demand for contemporary Polish art. It is not surprising that Sztuka's control over evaluation of Polish contemporary art and consequently over the market for contemporary art engendered resentment among those who, for whatever reason, were excluded from its ranks. Interestingly, this group included both artists who worked in more traditional modes as well as those who comprised the second generation of Polish modernism.53 |

||||||

|

We can see this resentment clearly in a satirical "poster" (fig. 9) created by Kazimeirz Sichulski, a young artist who studied under Sztuka members at the Krakow Academy, for an impromptu "show" lampooning Sztuka's exhibitions; the show was held in 1905 at a café named Michalik's Den (Jama Michalika), the site of the (in)famous Green Balloon Cabaret. In 1905, Sztuka organized three different exhibitions in Krakow: two solo shows for members Leon Wyczółkowski and Stanisław Wyspiński, and its annual group show. The new practice of hosting solo exhibitions followed on the heel's of Sztuka's direct involvement in production of the album Polish Art, which began appearing as a serial in November 1903. The album identified core Sztuka members as the foremost Polish artists and prominently featured both Wyczółkowski and Wyspiański.54 | |||||

| It is tempting to see Sichulski's poster-caricature (fig. 9), as a response to this escalation of rhetoric. In his drawing, the word Sztuka, reproducing the society's familiar logotype, appears prominently at the top of the page. The fact that the artist did not feel compelled to include the society's full name demonstrates that by 1905 the logotype functioned as a readily recognizable brand name logo identified with the group. In fact, Sztuka appears twice: as an iconic word and an image. In Polish, the word "sztuka" also refers to a "skillful trick," as in a circus act. The juxtaposition of the word Sztuka with the elephant, which seems to balance the word on the tip of its trunk, clearly points to this meaning.55 | ||||||

|

Of course, this visual pun is not meant as a compliment, especially when one considers the society's high-minded rhetorical self-presentation. The central pair of figures, likewise, aims to expose the society's pretensions. As we have seen in the official Sztuka posters, the concept of Art was frequently represented allegorically as a female figure, which stood for Art and for the society itself. In Sichulski's re-interpretation, this visual conflation is put to question. Sztuka, the society, is personified as a stooping, lumbering male figure, whereas Art is represented as a young female nude. The male figure, which recalls in demeanor caricatures made by Sichulski and others of Jan Stanisławski (fig. 10), the then current president of Sztuka, is likened visually to an elephant by an addition of a tail. He is the opposite of the youthful, graceful, and full of energy figure of Art. His static, bent, rear facing posture seems to invite a swift kick or a slap on the "arse." It also offers a perfect opportunity for a vault, which is readily taken by the female nude glancing mischievously at us over her shoulder. | |||||

| Considering the context and the function of female imagery in Sztuka's posters it is easy to see this allegorical personification as a direct, though perhaps not a very serious attack on Sztuka's rhetorical and institutional claims. By 1905, for Sichulski, an artist of a younger generation, Sztuka was not synonymous with Art. Its exhibitions were a preserve of respectable, i.e., conservative and academic, art practice, even if that practice was identified as "modern." His ironic and highly unflattering image purports to unmask the reality hidden by the official rhetoric. Instead of embodying Art, the society does not even notice, nor does it seem to care, where Art is and what it does. In this context, its name functions as an empty signifier—a brand name banking on past reputation, which, however, no longer identifies a quality product. It also suggests that by 1905 others were waiting in the wings ready to challenge its hegemony. | ||||||

| Conclusion It is clear that the "superior quality" of modern art does not account fully for Sztuka's success. While it may be true that the society tended to present works that subsequently have been judged to be "superior" or more accurately "historically significant," one must also remember that Sztuka played a key role in defining the criteria of artistic excellence and that it participated in production of the art historic narrative of the development of Polish art.56 It is also important to keep in mind that the Polish artists were not operating in a vacuum. The positive reception of their activities locally and regionally was conditioned by major shifts in the alignment of the European art system. By the late 1890s, the international art market fully embraced modernism in its many forms. Traditional academic painting was increasingly perceived as retrograde and, more importantly, anachronistic. Modern Art was widely believed to be the only legitimate form of Art of the Modern Era. In order to compete and garner positive attention abroad, Polish artists had virtually no choice but to work in a "modern" mode. Anything else would have marked them as hopelessly provincial. Even if their modernism did not make them competitive, it did allow them to claim at home that they belonged to the progressive European art mainstream. |

||||||

| But having a "good product" would not have been sufficient. As we have seen, the artists of Sztuka spent a great deal of effort positioning and promoting that product, namely Modern Polish Art; indeed, that can be understood to have been the society's main function. The exhibitions put on by Sztuka gave the public direct access to the members' work. If we carry the business analogy a step further, we can argue that Sztuka created a market for Modern Art in Poland where none existed before. It defined and differentiated itself from the competitors, helping to develop conditions in which Modern Art became synonymous with Art as such. In many respects, Sztuka's actions were reminiscent of those of other pioneering product developers who, at precisely this time, were filing new patents, creating consumer demand for new categories of products, and contributing to the development of new markets.57 And just as the success of those entrepreneurs created a demand for a whole range of previously unheard-of product categories bringing in scores of competitors, so did Sztuka's success eventually engender a similar response. It is quite clear that the proliferation of avant-garde groups in the 1910s and 1920s was to large extent motivated by Sztuka's dominance of the Polish art scene and, in that respect, could be seen as a direct outcome of the group's pioneering efforts. It is also important to note that many promotion strategies used by those later groups were initially introduced onto the Polish art scene by Sztuka. | ||||||

| In view of the information contained in the historic record and the visual evidence provided by Sztuka's posters and catalogues it is difficult not to liken the society to a firm developing a brand identity. However, the business savvy demonstrated by Sztuka's leadership does not in any way detract from their accomplishments. If anything, it should make us acknowledge the group's importance. It is my hope that this argument will encourage other art historians to seriously consider artists' groups as powerful players, rather than powerless cogs within the complex system of the art economy and to question such seemingly unproblematic and descriptive designations as Art or Modern Art. The history of Sztuka demonstrates that Polish artists acted deliberately and wisely to protect and further their own interests. At the same time, they were committed to their principles. The acknowledgement of one reality does not negate the other. | ||||||

| What we learn from Sztuka can be applied elsewhere. Although the specifics of each situation will be different, the general mechanism may very well be quite similar. Whether we acknowledge it or not, artworks are created in the context of professional practice. Particularly successful artists have always been good at negotiating their position and promoting themselves within the systems of symbolic and economic exchanges to which they belong. Although art historians may still think of Art and its history in absolute terms, any practicing artist knows that value and status (symbolic and economic) are produced and conferred and that all agents participating in this process, including artists, can affect the outcomes. | ||||||

| If we begin to draw on business and economic theory to explore further not only the behavior of the individuals and institutions that have already been considered with respect to the workings of art markets, but also the behavior of the primary producers of goods, namely the artists, we will likely have to abandon many cherished assumptions and preconceptions concerning the history of modern European art. An examination of the complex interactions among all participants—the producers of objects, the journalists and historians, the dealers and patrons, the public at large, the state officials, etc.—will no doubt lead to a much less clear-cut picture than the one resulting from the standard accounts of the development and spread of modernism in Europe. In fact, the spread and success of modernism will have to be addressed not as a given, but as a problem.58 A great deal of work remains to be done across the entire field. The analytic model proposed here may also apply in other temporal and geographic contexts. Undoubtedly, the exceptions will prove as interesting as the cases that will follow the general rule. What is needed is further exploration and refinement, careful case studies of the historic evidence that will either support this thesis, lead to its modification, or prove it inadequate. | ||||||

|