X

Please wait for the PDF.

The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|||||||

|

Philippe Kaenel, Eugène Burnand (1850-1921), peintre naturaliste |

|||||||

| With the recent exhibition in Lausanne dedicated to the work of Eugène Burnand (1850-1921), a lacuna in the understanding of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Swiss painting has been filled. Long regarded as an enemy of modernism, Burnand must now be seen differently. With this exhibition and the exhaustively-researched catalogue written by Philippe Kaenel, it is possible to see Burnand not in opposition to the modernism of Ferdnand Hodler, but rather as a Swiss painter inspired by his homeland and motivated by the mainstream currents of naturalism from outside his native country. Now that we can see a large body of his work and the first detailed study of his accomplishments, Burnand appears far more creative than originally thought, more deeply involved in issues of his time, and certainly deserving of increased recognition. With proper consideration of the exhibition and publication, it is not possible to neglect Burnand's work ever again. Kaenel's catalogue positions Burnand's work in its historical context while demonstrating that the artist was extremely sensitive to, and fully involved with, many of the major anti-modernist issues of his era. | |||||||

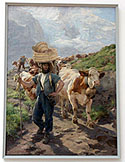

| In the first section of the publication Kaenel carefully situates Burnand within the tradition of animal genre painting that reaches back to the works of Rosa Bonheur, while tying the artist to a lucrative popular tradition. As a student, Burnand trained in Paris with Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the younger teachers at the École des Beaux-Arts, and gained the confidence of his fellow students including Jules Bastien-Lepage and P.A.J. Dagnan-Bouveret, among others. In the company of these young French artists, Burnand was exposed to discussions about the aesthetic aspects of positivism and the tradition of recording modern rural and urban life under the rubric of naturalism. At the Paris Salons, Burnand received numerous awards for animalier studies that showed a strong ability to grasp the character and personality of animals, linking him not only to Bonheur or Constant Troyon, but also to his naturalist contemporaries such as Alfred Roll, Julien Dupré, or Georges Laugée. By 1884, with his Taureau dans les Alpes, Burnand created his signature image, the work with which he was continually identified and one that best exemplified the artist's ability to convey the rural beauty of Switzerland. Here the desire of Swiss farmers to give farm animals a position of powerful dominance in their lives was clearly articulated. Against the backdrop of the Alps in the distance, a single bull bellows, creating the impression of an echo from his roar. While Burnand produced many other paintings on a gigantic scale during the 1880s and 1890s, this canvas, in the eyes of the public, defined his success. But in a most subtle way Kaenel raises the issue of whether this was the only way to see Burnand's creativity. Was his fame as an animalier linked to Swiss rural life or was there something much more compelling in his position as creator? The other sections of the book respond to these queries by presenting a comprehensive picture of Burnand's life and career. | |||||||

| The second chapter moves into a little-examined phase of nineteenth-century artistic activity. As one way to earn a living, and to make a name for himself, Burnand worked in the graphic arts (as was the case with others such as Dagnan-Bouveret and especially Emile Friant). He submitted drawings to the editors of popular magazines, such as L'Illustration. These were used as the basis for illustrations that appeared with regularity during the late 1880s. Because Burnand could work quickly and accurately, he was hired as an illustrator of popular working types: collectors of coal, sowers in the fields, and even penitent woodsmen praying at a roadside cross. In each of these instances Burnand's style was exacting, detailed, and easily comprehensible to a reader. As his reputation grew, book editors realized that Burnand could become an illustrator for luxury books capable of effectively visualizing literary texts. Whether as a magazine or book illustrator, Burnand was open to the newest publishing techniques, even to the ways in which photography (of which he became a devotee) could be useful to the creative artist eager to remain progressive. | |||||||

| With his panoramic pastoral views of the Alps, Burnand contributed to the debate that dominated the academic painters of the era regarding the position of landscape in the hierarchy of genres. (figs. 1-10) Avant-garde painters, such as the Impressionists, had demonstrated that it was the landscape where formalistic innovations took place. Academically trained painters tried to challenge this belief, Burnand among them. By presenting vast vistas that completely absorbed a viewer into the scene, Burnand (with the assistance of helpers) created objective views of mountains, valleys, and the atmosphere of rural Switzerland. Aided by studies made on location, and photographs of specific sites, Burnand contributed to the discussion of how it was possible, or not, to paint reality. Burnand's views of the countryside also engaged with another contemporary issue: the possibility of articulating a national identity through landscape. By painting very specific mountains and valleys, the artist gave Switzerland a tangible identity to the outside world at the same time that it shaped the nation's self-image. The artist's ability to capture the light and atmosphere of Switzerland showed how Burnand's vision of the academic landscape was integrated with progressive developments while also suggesting that the landscape itself could contain religious symbolism. | |||||||

| At the heart of the debate over what an academic artist could paint was the role of history painting in the late nineteenth century. Influenced by the direction of Gérôme, Burnand did a series of small history canvases that found their origin in characters from the past such as views of Louis XIV during his last years. Responding to the call to create a large canvas recording the Fuite de Charles le Téméraire, Burnand used all of his training to convey what appeared as an accurate reconstruction of the past while presenting a pre-cinematic impression of figures moving through time and space on an extremely large scale. While Burnand did not, as Kaenel's essay reveals, remain a pure history painter, his large-scale renditions of history or the landscape of his native country eventually included religious themes. | |||||||

| During the first decade of the twentieth century, in response to a general renewed enthusiasm among artists, both in Europe and in the United-States, to humanize Christ, Burnand moved toward the completion of panoramic images of Christ on the Via Dolorosa. Burnand's friend, Dagnan-Bouveret, completed mystical scenes based on similar themes. Burnand was basing his vision of Christ on the writings of Ernest Renan who had done much to help individuals focus on Christ's humanity since the 1860s. As a naturalist, Burnand also concentrated on another conception of religion that Kaenel ably discusses: he was determined to show in his religious compositions only what could be tangibly understood. Such paintings as Les Disciples (1898), in focusing on two figures in the foreground plane, reveals religion through the recording of human conduct and passion. There is little that is supernatural in this or in his other works. Kaenel demonstrates how Burnand constructed his religious subjects; documentary photographs reveal how the painter found his models and how he painted in his studio to achieve his effects. | |||||||

| The author also raises a very significant question about patronage: who commissioned these exceptionally large paintings and where were they displayed? While Swiss churches could not always effectively show them, Kaenel does document that at least one work was secured by the American department store magnate John Wannamaker for exhibition in his Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia. While this avenue of research is not pursued very far, Kaenel reveals that there was an American gilded age market for large-scale religious paintings that could teach a public audience through the ability to convey a religious experience specifically and on a large scale. In opening this aspect of Burnand's work, and in showing that there were other European artists working in a similar vein, Kaenel does a vast service toward suggesting that religious imagery of a new type needs to be effectively studied. He initiates this discussion by examining the role of religious painting in Burnand's oeuvre, and the influence of protestant religious thinkers about how to represent Christ. | |||||||

| In the next chapter, Kaenel shows how Burnand was committed to three different projects that stressed the need for interpretive illustrations. Whether concentrating on images of a pilgrim's passage through life or the parables that suggest an inner spiritual existence, Burnand's next projects mirrored an even more contemplative mode that demanded that the artist mold his way of life to the subject at hand. He retreated to quieter locations, living his life as if he were a monk retreating into his own thoughts. When Burnand depicts a shepherd resting with his flock, his painting conveys an inner spirituality; it is this intense quality that makes another of his canvases, the Retour de l'enfant prodigue, so moving. By using his own likeness as the old man in the painting, Burnand effectively conveys a sense of personal spiritualism. In drawings of various Biblical types for book illustrations during the first decade of the twentieth century, Burnand also is seen as continuing Rembrandt's religious intensity. However, in spite of these works, Kaenel notes that there was considerable controversy in France about Burnand's religious imagery; the artist was criticized for trivializing the religious experience and failing to convey a sense of Catholic mysticism. What these French critics obviously failed to understand was Burnand's stated realist and "Calvinist" interpretation of religious themes. | |||||||

| It is just at this moment in the evolution of Burnand's career that Kaenel takes a step back in order to reconstruct the artistic debates in Switzerland around 1900. At this time Burnand and Hodler, who were originally on friendly terms, were seen as the two diametrically opposed poles of Swiss painting. Even though Burnand and Hodler were both believed to possess a strong moral foundation, Hodler was also viewed as a revolutionary, an artist who came from a background of revolt and change. Burnand, on the other hand, was a painter who wanted to maintain tradition; he upheld the values of bourgeois life and refused to challenge it. Despite these differences, Kaenel subtly reveals just how close to the modern position Burnand was during the 1890s since his landscapes were in the forefront of creativity, and in some instances even challenged the work of Hodler. However, Hodler was the winning artist; his paintings were seen to be more subjective, and symbolist, as he infused his imagery with a greater sense of mystery. Even though Burnand had a degree of popular success at the time, his paintings were often critically savaged for being too literary, too theatrical. Eventually, since Burnand did not have a substantial power base with progressive critics, he was excluded from the modernist canon. Forced into a closed world, one outside of Lausanne, the artist's fame was seen to rest on past triumphs and an older perception of the world. Switzerland was now his permanent base and Burnand was content to remain there. This very carefully argued chapter, one of the best in the book, provides a touchstone for seeing the confluence of two traditions interconnecting and moving away from one another in the period just prior to World War I. | |||||||

| In the next chapter Kaenel reconstructs the ways in which a tradition-bound artist could continue to create and have a successful career. Kaenel discusses Burnand's turns to portraiture, then an artistic genre struggling for its very existence in face of the inroads made by photography. Since Burnand had extensive connections with wealthy and powerful families, he was called upon to paint studies of key members of various clans. In these paintings, often bust-length studies done in meticulous detail, Burnand finds a sense of the inner character of each posed model. Without relying on the setting for each individual, Burnand manages to document a wide range of modern types—albeit from the wealthiest classes in society—as he identifies the appropriate visual traits of what he might see as typically Swiss. These individuals are educated, well mannered, intellectually alert and intensely proud. These are qualities that he finds to be central to the Swiss character. This same attitude is maintained in Burnand's later studies of soldiers or warriors published between 1919 and 1920. | |||||||

| In the remaining two sections, Kaenel reiterates the basic themes that Burnand worked with throughout his career. In late, large-scale paintings, he notes that Burnand held onto the values of peasant life and work at a time when these were attacked. His Le Labour dans le Jorat, 1915, a canvas that was destroyed, is seen not only as a gigantic panorama but also a work whose imagery was rooted to the soil, the landscape of Switzerland itself. In noting that critics seldom discussed this painting, Kaenel finds another clear instance where Burnand was seen as a symbol of anti-modernism; his work was regarded as being out of touch with what was progressive. In reiterating Burnand's ability to document the naturalistic work ethic Kaenel reveals that the artist had found themes that were eternal: the peasant was seen as noble, the countryside as a locus where diligent work was maintained. In the end the peasant was regarded as a symbol of the eternal ability of humanity to survive in society no matter the changes. Kaenel's final evaluation of the painter is also apt. Burnand chose a path of creativity that allowed him to flourish in a largely bourgeois stable country; he created works that were valued and which allowed him to have a substantial, lucrative career. Toward the end of his life, Burnand found, just as his friend Dagnan-Bouveret did, that some of his power was slipping away; he was seen as old-fashioned, as someone whose time had passed. Yet, Burnand's determination to maintain his right to exhibit what he wanted, where he wanted, made him heroic. Though he has been left out of the histories of Swiss art and eliminated from the general studies of modern creativity, Kaenel believes his work must not be seen as reactionary. | |||||||

| When assessing a book such as this one it is essential that Kaenel's ability to reconstruct Burnand's contribution and place in history be seen concretely and cohesively. As a catalogue to an exhibition, to an event that brought a once well known painter out of obscurity, the publication is handsomely produced, with a careful integration of works that were actually in the show set against documentary materials that visually illuminate the ways in which the artist created. Additionally, the catalogue functions as a document that will have a much longer life than the exhibition. Kaenel has demonstrated that Burnand is one of the primary anti-modernist painters of his era, an artist who understood the main tenets of Swiss existence and who was able to provide visual evidence of the life and times in which he lived. Better than many other artists, and similar to the work of Dagnan-Bouveret, the French academic with whom he can best be compared, Burnand's most impressive compositions provide an alternate view of reality. Burnand's compositions, with their ability to record things as they appeared, provided new vigor to the reign of naturalism at a moment when it was being most severely attacked by abstract modernists. The fact that Kaenel provides such a rich history, filled with original insights into Burnand's career and life, demonstrates that this book will be consulted for years to come. By showing how Burnand's work transcended the period in which he lived, the author provides a significant interpretive base for an artist whose imagery will now be better understood. It is too bad that the exhibition could not travel and the catalogue was not given a wider distribution. | |||||||

| Gabriel P. Weisberg Professor of Art History University of Minnesota weisb003@umn.edu |

|||||||