The browser will either open the file, download it, or display a dialog.

|

|

Anti-Catholicism in Albert Bierstadt's Roman Fish Market, Arch of Octavius |

|||||

|

By the end of 1858, the American artist Albert Bierstadt had come home to New Bedford, Massachusetts after four years of study in Europe, made his National Academy of Design exhibition debut in New York, where he had been elected an honorary member, and sold "near four thousand dollars worth of pictures" since his return to America.1 One of the paintings Bierstadt sold that year was Roman Fish Market, Arch of Octavius (fig. 1, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco), recently described as "perhaps his most accomplished genre painting."2 Roman Fish Market was one of several canvases that resulted from Bierstadt's travels around Switzerland and Italy in 1856 and 1857. He sold the work for four hundred dollars to the Boston Athenaeum, where it was displayed in annual exhibitions fourteen times between 1858 and 1879.3 |

||||||

| What was the particular appeal of Bierstadt's Roman Fish Market to the trustees and visitors of the Athenaeum? How might he have planned it with a Northeastern audience in mind, and why might it have engaged viewers in Boston? Finally, what cultural message did the painting communicate in 1858 and over the next twenty years? This painting, whose ostensible subject is a fish market at the Portico of Octavia—the Arch of Octavius in the title is a misnomer—contains paradoxes that reveal Protestant attitudes about Catholic immigrants settling in the northeastern United States. Although it dramatizes a Yankee tourist couple surrounded by poor, swarthy Romans, Bierstadt's picture can be read as an allegory of anti-Catholic, anti-Irish sentiment. Virulent anti-Catholicism was rife in late antebellum America, and was spread especially by travel writers, newspaper editors, and politicians. Using the "picturesque" contrast between the ruins of antiquity and the squalor of contemporary Italians, Bierstadt reflected popular opinion and explored the tension between immigration and American republicanism. As Bierstadt's only known urban image, Roman Fish Market expresses the anxiety of the Northeastern, urban, Protestant elite regarding economic and political change, and its fear of the political and social impact of an Irish Catholic working class in the United States. | ||||||

| Bierstadt's scene shows a road extending from the center foreground into the distance, passing through a fish market and into the Jewish ghetto of Rome. Crumbling brick and concrete arches provide a setting for the market, and the shape of the foremost arch echoes the shadowy archway that dominates the middle ground. This second arch opens onto a view of contemporary Rome, with clothes hanging between multi-story apartment buildings, cluttering a bright blue sky. The sunlight falls from upper left to lower right, casting strong shadows across the market in the foreground. One shadow, from the capital of the foremost archway, falls diagonally in the direction of a Yankee couple. A man dressed in the colors of the U.S. flag—red vest, white shirt, and blue coat—and a woman in a yellow dress, green shawl, and hat with veil, walk among the Romans and fish stands. Bierstadt's male tourist might well be, in Margaret Fuller's words, the "thinking American... anxious to gather and carry back [from the Old World] with him every plant that will bear a new climate and new culture." Continuing the horticultural metaphor, Fuller wrote that such an American hoped to gather his "plants... free from noxious insects" yet did "not neglect to study their history in [the Old World]."4 The tourist's female companion glances backward as if shocked, bewildered, or nervous about something behind her. | ||||||

| This prim and proper American gentleman carries under his left arm a bright red copy of Murray's Handbook of Rome and Its Environs. Evidently following the detailed written tours in the guidebook to discover this ancient site off the beaten track, the man attempts to ignore the beggar to his right, dressed in brown and tipping his hat. Italians fill the marketplace and portico, the walls of which carry several torn and partially faded theater announcements. Rather than crowning columns or bracing grand architecture, gigantic capitals support the slabs of marble used to display a cluttered variety of fish.5 | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Bierstadt was born on 7 January 1830 near Düsseldorf, and his family immigrated to New Bedford when he was two years old. Little is known about his early training, but by 1851 he was offering a course in monochromatic painting. In 1853, he traveled to Düsseldorf with plans to study under Johann Peter Hasenclever, a distant relative. This city on the Rhine with its renowned art academy had become a destination for artists from around the world. When Bierstadt arrived, however, he found that Hasenclever had died. Although Bierstadt never did attend the academy, he worked closely with Americans compatriots, including Emanuel Leutze and Worthington Whittredge. In June 1856, Bierstadt, along with Whittredge and William Stanley Haseltine, went on a sketching tour through southern Germany and Switzerland, where they met up with fellow artist Sanford Robinson Gifford at Lake Lucerne. After weeks of hiking and sketching in the Alps, the group traveled the Saint Gothard Pass to Lake Maggiore. Following a brief stay in Florence, Bierstadt continued on to Rome, and then, with Gifford, on foot throughout Abruzzi, to Naples, Capri, and the Amalfi Coast. Paintings based upon these European travels, including Roman Fish Market and Lake Lucerne (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), were among those he showed in 1858, in New Bedford, Boston, and New York.6 | ||||||

| When he returned to Massachusetts in 1858, Bierstadt would have found the state sharply impacted by the ongoing immigration of poor, unskilled Irish Catholics. In the previous century, Anglo-Saxon Protestants in North America had not looked favorably on the Irish for political and religious reasons, and this animosity continued with the tremendous influx caused by the potato blight in Ireland. Some 914,000 Irish came to the United States in the 1850s, with 170,000 arriving in 1852 alone. According to the 1850 census, more than 48 percent of Boston's labor force and 15 percent of the city's domestic servants had been born in Ireland. According to the 1865 "Annual Report of the Chief of Police," 75.8 percent of arrested and detained individuals were born in Ireland.7 The "famine Irish" arrived at a time when elite and middle-class Bostonians viewed themselves as emblematic of a progressive national culture. Recent scholarship has examined how New Englanders, with their unique regional character, were inclined to present their views as representative of the nation as a whole.8 The Boston Athenaeum was one of many organizations in antebellum America through which the urban upper class expressed its interests and social preferences.9 | ||||||

| Members and patrons of the Athenaeum were among the voters who, in the Massachusetts state elections of 1854, gave the Know-Nothings—a grass-roots political party with an anti-establishment, nativist outlook—the governor's seat, the entire state senate, and all but two seats in the state house of representatives. Members of this party pledged to protect the "vital principles of Republican Government." Catholicism would and did, in the eyes of Know-Nothings, subvert American freedoms and republican values. Mostly poor and uneducated, the newly arrived Irish were seen by New England nativists as easy prey for "bread and circuses" and the rhetoric of shifty demagogues. By the time Bierstadt exhibited Roman Fish Market in 1858, the nativism and anti-Catholicism of the Know-Nothings had been somewhat eclipsed by the issue of slavery, but would re-emerge in the political arena following the Civil War.10 | ||||||

|

|

||||||

|

In November 1858, America's most important art journal, The Crayon, offered its "Reflections" on immigration and the upcoming census of 1860. In their own words, the magazine's editors sought to place art "within the wider context of a desire for human progress and perfection." Noting that the U.S. population was expected to grow to thirteen million people, and that this was due in large part to the influx of three million immigrants, the editors opined: "As far as the masses of foreigners are concerned, who contribute so much to swell our population, they have long ceased to offer any charms of novelty." The Crayon termed the majority of immigrants "inferior in education and intelligence to corresponding American classes," and characterized the Irish as "childlike" if one could even see through their "most grotesque stupidity." The editors berated the Irish:

According to The Crayon, "picturesque" Catholic Irishmen, "inferior" to Protestant Anglo-Saxons, threatened to ruin the republican freedoms of the United States.11 |

||||||

| The Know-Nothings openly condemned the U.S. immigration policy that admitted so many non-Anglo-Saxons. In his 1855 inaugural address, Massachusetts's Know-Nothing governor, Henry J. Gardner, stated that four million foreigners would arrive in the 1850s alone, bringing with them the social ills of crime and pauperism. Far-reaching measures were needed "to purify and ennoble the elective franchise" and "to guard against citizenship becoming cheap."12 Gardner was referring specifically to the largest ethno-religious minority group in Massachusetts, Irish Catholics. Many residents were less concerned about Kansas and Nebraska becoming slave states than they were about the prospect of poor, unskilled immigrants crowding the cities, forcing them to move west. Bierstadt's unruly Roman Fish Market, therefore, resonated with its Protestant viewers, who were anxious about what Boston—and by extension, the country's republican institutions—might become with the population influx of Irish Catholics.13 | ||||||

| In Bierstadt's painting, the squalid Roman fish market is situated in the Portico of Octavia, part of a building program undertaken during the waning of the ancient Roman republic. The portico was an architectural feature of a complex of buildings that, like Boston's Athenaeum, included libraries and an art gallery. Named for Octavia, the sister of the emperor Augustus, the portico originally bordered on the Forum Holitorium, the ancient produce market. The fish market occupied this site from the twelfth century until the late nineteenth century. The surrounding neighborhood became the Jewish ghetto, a gated city within Rome where Jews were confined until the Risorgimento. Bierstadt depicted the fish market with his back toward the church of S. Angelo in Pescheria. The crumbling brick and concrete arches of the portico represent the destruction of a grand civilization, since "barbarians" and popes had stripped its marble cladding from the façade for their own purposes. Murray's Handbook described the Portico of Octavia as in "ruins... situated in the Pescheria, the modern fish-market, one of the filthiest quarters in Rome."14 | ||||||

|

Many American travelers, including the Bostonian scholar Charles Eliot Norton, blamed modern Romans for the city's decay: "What war and fire and the ravages of barbarian conquerors left of ancient splendor, the Romans themselves, still more barbarian—people, princes, and popes—have conspired to destroy."15 The prominent expatriate sculptor William Wetmore Story, in his Roba di Roma of 1862, noted:

Before the once-grand architectural achievement of Augustus, the "republican prince," stood now a fish market with all its grime and odors. Bierstadt framed the actors in his scene with the proscenium-like arch, giving it the feeling of a tableau vivant or opera set. |

||||||

| Roman Fish Market transports viewers into the center of the Eternal City, filled with poor, unskilled, Italian Catholics—ne'er-do-wells incapable of republicanism. In the eighteenth century, European artists like Giovanni Battista Piranesi and Hubert Robert emphasized the grandeur of the Portico.17 Instead, Bierstadt focused on the disarray of the fish market, using the ruins as a backdrop to signify the deteriorating splendor of Rome. Charles Edwards Lester, great-grandson of the minister Jonathan Edwards, and U.S. Consul in Genoa from 1842 to 1847, summarized what America could learn from the "moral power" of ancient monuments in Italy: "Monuments of all kinds are intended to illustrate noble deeds, and the feelings of the beholder partake of the associations they are designed to awaken."18 Politically and intellectually, however, contemporary Catholic Rome was anathema to pre-Civil War American democratic values. The Portico of Octavia serves as a backdrop for the fish market's idlers, beggars, and gamblers, even as its evocation of the past lent the scene a picturesque appeal. As one American traveler wrote in 1853, "The charm of cleanliness belongs neither to Rome nor its people... But in Rome even dirt becomes picturesque."19 Roman Fish Market is thus a repository of ironies and incongruities, reflecting Americans' ambivalence toward Rome. Rome's very picturesqueness underscored the degenerate condition of its people living under monarchical, Catholic institutions.20 | ||||||

|

Bierstadt utilized light and chiaroscuro in Roman Fish Market to draw viewers' attention to specific acts of immoral behavior and to spotlight the encounter between the American tourists and Roman beggar (fig. 2). Indeed, light and dark, which often suggest the movement from one realm into another, are used here to designate the market as a site of contrasts. Augustus J.C. Hare, in the 1874 edition of his Walks in Rome, recommended that the Portico of Octavia be viewed by morning light:

Bierstadt's motif of the beggar pestering the Yankee tourists would have evoked strong, familiar feelings in those Protestant New Englanders who had traveled to or read about Italy. Americans visiting Rome expected to experience poverty; seeing the beggars was considered desirable since this enhanced the authenticity of one's tour. The encounter in the painting occurs as if on a stage, with Rome as its backdrop, and with all parties performing for an audience. Guidebook at hand, the tourists enact the ritual of moving from ancient site to ancient site, gathering knowledge and ennobling experiences. Bierstadt's image calls to mind what Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett has termed "the major tropes of ethnographic display." His tourists, like the viewer, penetrate the everyday world of the Romans, experiencing "the people" when they are most "themselves." The Americans' attitudes, with the woman's frightened glance and the man's contrived stoicism, express a heightened, liminal state. Both they and the viewer have removed themselves from New England's ordinariness to discover, in a multi-layered experience, Rome's extraordinariness. Bierstadt has framed the scene in the archway, much as the tourists attempt to frame and control their experience of Rome. Viewers witness a common incident—tourists lost in a labyrinth—but one charged with meaning.22 |

|||||

|

Antebellum American commentators often noted Roman vices, especially beggary. Story observed that "begging, in Rome, is as much a profession as praying and shopkeeping. Happy is he who is born deformed, with a withered limb, or to whom Fortune sends the present of a hideous accident or malady; it is a stock to set up trade upon." Making connections between idleness and the Catholic church, Story continued:

For Story, "the restrictive policy of the [Roman Catholic] Church," in contrast to the "industrious" character of U.S. Protestantism, caused idleness, beggary, and vice; if only the church of the "grand and noble" Romans would promote freedom of thought and action, then beggary would disappear. Americans in the 1850s believed that the Italian people had been prevented, by the tradition and power of their church, from advancing in science, art, and technology. Instead the church engendered superstition, poverty, and indolence, and perhaps worst of all, was tyrannical and undemocratic. |

||||||

|

The mainstream press regularly blamed similar social problems in the U.S. on the Catholic church and its Irish adherents. For example, a series of anti-Irish cartoons that ran in Harper's Weekly on 7 November 1857 included one showing a footless and disheveled beggar with the caption "IRISH BEGGAR to generous Young Lady: 'Thank'ee, Miss; but I niver takes country money'" (fig. 3).24 This caption suggests that Irish beggary, like Roman vice, was strictly an urban phenomenon. Politician Thomas R. Whitney, writing about Irish immigrants in 1856, argued that "to believe that a mass so crude and incongruous, so remote from the spirit, the ideas, and the customs of America, can be made to harmonize readily with the new element into which it is cast, is, to say the least, unnatural."25 His statement could just as well apply to Roman Fish Market, in which "crude and incongruous" Italians (symbolized by the beggar) contrast with the "spirit... of America" (symbolized by the Yankee tourists and the ancient republican setting), and create an anxious, unnatural situation for Americans traveling abroad. The chief virtue that a poor, urban man or woman could display was industry. Even so, well-to-do Americans had to maneuver around and through the poor, whether Irish, in their own communities, or Italian, as in Bierstadt's painting. Although Bierstadt's audience would have considered the denizens of his Roman Fish Market more physically attractive than Irish immigrants in Boston, the political and religious discourse of the 1850s conflated Italians with the Irish. Indeed The New Bedford Mercury, in a telling slip, confused the subject of Roman Fish Market upon its sale to the Boston Athenaeum: "Mr. Bierstadt has disposed of his oil painting... of the 'Irish Market' or 'Arch of Octavius'."26 | |||||

|

|

||||||

|

The Irish, as caricatured in the Harper's series, fight, live among dogs, imbibe alcohol, and openly corrupt the American naturalization and political processes. This too has its analogue in Roman Fish Market. To the left of the male tourist, four men appear to be playing morra, a game of chance. The Italian in a green coat points with his right hand while he puts his left hand into his pocket. The other three men look down and hunch over. Story described the game of morra:

Instead of engaging in market commerce, Bierstadt's Romans gamble and drink. |

||||||

|

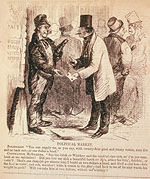

Other cartoons in Harper's during the late 1850s addressed political corruption and the presumed Irish unfitness for American democracy. Just as the Romans misuse the ancient portico, the "fitin', drinkin', or votin'" Irish desecrate a revered locale: the polling place (fig. 4).28 In this image of 1858, entitled "Political Market," votes—rather than fish—are for sale. A cigar-smoking politician approaches "Contractor McDabber," offering to pay one dollar per man for "good and trusty voters." At left, the willing Irishman, thin pipe in his mouth, reaches out to receive cash for his vote. In the background, simian-like Irishmen mill about. According to the caption, McDabber barters with the politician, requesting not only a dollar, but also a drink of whiskey for each vote he can deliver. The cartoon parodies both the professional politician and the ignorant Irish voter who fails to understand the responsibility that accompanies suffrage. The Irish, having emigrated from a Catholic environment that, according to nativists, created sloth and drunkenness, become willing dupes of corrupt politicians. Irish votes in America are bought and sold for cash and whiskey just as the wages of Bierstadt's morra-playing Romans, ignoring the republican symbols of their surroundings, are wasted on petty gambling and wine. | |||||

|

Other colorful but disheveled Romans in Bierstadt's painting signify what tourist and art critic James Jackson Jarves described in 1856 as the Romans' "profound aversion to labor."29 A man in the right foreground sleeps on the job, a broom propped against his arm. His pose echoes that of the celebrated second-century marble relief of Endymion Asleep, which was on display in the Capitoline Museum during Bierstadt's stay. The artist's suggestion that the splendor of ancient Rome has been distorted continues in the barefoot fisherman asleep nearby on the mat of straw. This figure directly quotes an ancient sculpture that once was also in the Capitoline collections, the Barberini Faun, which depicts a drunken satyr (fig. 5).30 | |||||

| On the shadowed wall behind the tourists, a weathered broadside announces a production of Medea starring the Italian actress Adelaide Ristori, at the Teatro Metastasio. Ernest Legouvé's adaptation of Euripides's tragedy toured Italy during the winter Bierstadt spent in Rome. Legouvé's play involves immigration, in that Jason and Medea must flee to a new home in Corinth. When the play opens, Medea has just discovered that Jason, the father of her sons, has secretly married the daughter of Kreon, the king of Corinth. Kreon, fearing retaliation, decides to exile Medea with her two young sons. Seeking shelter in Athens, Medea poisons Kreon and his daughter, and later kills her sons to punish Jason. Like Euripides and later adapters of this classical tragedy, Legouvé carefully builds the suspense toward this shocking climax. A major theme in the tale is that unchecked emotion overcomes reason. Yet Medea's treachery in Athens carries another theme, one that would have resonated strongly with an American audience anxious about Catholic immigration. In a passage that recalls the American belief in Manifest Destiny, the Athenian chorus refers to itself as "children of the blessed gods, born from a sacred, unravaged land, feeding on cleverness that is most glorious." Euripides's Medea is not Athenian, not even Greek, but a foreigner from distant Colchis, both an "other" and a sinister, magical transgressor. The chorus asks how Athens, in light of its civilized values, could absorb the story of Medea. Bierstadt, in Roman Fish Market, posed a similar question to his American audience: How can a nation with republican, democratic values incorporate individuals so seemingly different into its civic body?31 | ||||||

| Bierstadt includes still other references to antiquity in his painting. The pose of the woman standing with a distaff and spindle, near the center of Bierstadt's composition, resembles the antique draped figure of Modesty, in the Vatican Museums—sometimes identified as Livia, the wife of Augustus. (Story's sculpture of the 1860s entitled Medea [fig. 6] was probably also based on this classical model, and was most likely inspired by Ristori's Medea.)32 Bierstadt's spinner appears near the drunk and sleeping men, and thus Modesty has been transformed into a peasant keeping company with low-life characters. She functions, like her male counterparts, as a not-so-subtle reminder of the lost glory of ancient Rome and the diminished morality of papal Rome. | ||||||

| This woman turns her head in the direction of a mother and child seated near a still life of dead dogfish and rays. As in a vanitas painting, this nature morte refers to the transience of life and, perhaps more specifically here, to Medea's dead sons. The motif of the mother and child, which may quote Michelangelo's Pietà in the Vatican, recalls a scene from Legouvé's play in which Medea caresses her children before murdering them. Bierstadt related the mother and spinner not only through the latter's turned head and their positioning back to back, but also through the diagonal that begins with the poster and stretches through the standing woman and on to the mother. The play's presentation of a destructive-but-wronged female evoked feelings of fascination, pity, and repulsion in viewers, and mid-nineteenth-century Rome itself had the same effect on American visitors. The paradoxical juxtaposition of a theatrical performance (connoting high art and order) and a putrid fish market (suggesting real life and disorder) would have simultaneously fascinated and repulsed Bierstadt's American viewers, as it did the Yankee tourists.33 | ||||||

|

These figures inspired by statuary relate to replicas of antique sculpture in American art museums of this period. Such plaster casts were, according to trustees and founders, "the means by which the museum-going public was to acquire the benefits of higher civilization."34 The selection of casts revealed a predilection for certain examples, then considered masterpieces, of ancient and Renaissance sculpture, and established Protestant Americans' claim to the legacy of these civilizations. The Boston Athenaeum, which housed both a library and art gallery, displayed numerous sculptural reproductions (fig. 7). For the Athenaeum's first sculpture exhibition in 1839, a total of eighty examples were shown, with over one third being plaster casts of classical statuary. A reproduction of the Barberini Faun, upon which Bierstadt based his sleeping fisherman, was on display there from 1858 through 1867.35 Through such references to antique statues, Roman Fish Market functioned as a painted ethnographic "sculpture" display. Yet Bierstadt inverted their "civilizing potential," for his three "replicas," surely recognizable to cognoscenti at the Athenaeum, represent the civilized turned barbarian. | |||||

| The chaos in Roman Fish Market contrasts with the orderliness that characterizes other American images showing marketplaces in the 1850s. Two examples are Nathaniel Currier's 1856 print Preparing for Market (fig. 8) and Faneuil Hall Market Before Thanksgiving, an illustration in Gleason's Pictorial Drawing Room Companion (fig. 9). The former, based on Jerome Thompson's painting of the same title (displayed at the Boston Athenaeum in 1855), shows an agricultural bounty linked to progress and innovation. The profusion of healthy adult animals and their offspring brings into even sharper relief the death and decay shown in Bierstadt's scene. Likewise, in the Gleason's illustration, the meat hanging neatly provides a stark contrast with the fish strewn about the Roman market. In nineteenth-century America, the public market served as a trope of a civic, moral economy. Such markets, which could be found in every major city in the country, had their distant origins in republican Rome, for example, the Forum Boarium and the Forum Holitorium, forerunners of the market depicted by Bierstadt. Unlike Bierstadt's fish market in Rome, the orderly activity in Boston's Faneuil Hall reflects the civic economy of a republic.36 | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| The "otherness" of Rome, then, constitutes the principal theme of Bierstadt's painting. His American tourists have come to see the Italy of the past, not of the present, and thus are bewildered by the chaos of the fish market. By classifying Italy as the site of both antiquity and Catholicism, Americans defined themselves as modern and progressive, as culturally (and morally) distinct from contemporary Romans, and as the rightful heirs to the legacy of republicanism. The filthiness of the street, crumbling portico, and use of ancient ruins to sell fish convey a disregard for the lessons of antiquity and suggest that Catholicism retards human enlightenment. Pushing past these unkempt Italians, the visibly disconcerted Americans cling to their guidebook as they make their pilgrimage of antiquity. Indeed, Bierstadt's Roman Fish Market served as a visual "guidebook," one that instructed Protestant Bostonians in what to see and how to see it, as they sought to make sense of their own changing society. | ||||||

|

Author's Note: The main ideas in this article were developed for Kenneth Haltman's graduate seminar on American genre painting at Michigan State University in 1999. The ideas have been presented, in various manifestations, at several conferences and lectures. The manuscript also appears, in very different form, as a chapter in my dissertation "Classic Ground: American Paintings and the Italian Encounter, 1848–1860." I thank Bruce Levine, Raymond Silverman, Victor Jew, David Cooper, Kimberly Little, Patrick Lee Lucas, the staff of the Georgia Museum of Art, the participants at my presentations, the anonymous peer reviewers, and Peter Trippi and the editors for their attentive criticism of various drafts of this essay. I also thank Kenneth Haltman for his patient and thoughtful mentoring of this manuscript from its very beginning. For Michelle. 1. Although the painting is mentioned briefly by The Evening Standard of New Bedford, Massachusetts on 8 July 1858, there is no record of criticism or contemporary interpretation from the painting's exhibition in the 1850s through the 1870s. See Anderson and Ferber 1990, p. 135, for the comments from the Standard. The quotation "near four thousand..." is dated 1 November 1858 in correspondence between H. Lewis to G. Lewis, Henry Lewis Papers, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and quoted in Anderson and Ferber 1990, p. 124. 2. See Nancy K. Anderson's opinion of Roman Fish Market in Anderson and Ferber 1990, p. 69. 3. The selling price and exhibition information come from the object record for Roman Fish Market, Arch of Octavius in the American Paintings Department of The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. For more on the painting, see Marc Simpson 1994, pp. 138-140; and Baigell 1981, pp. 18-19. For a detailed list of works of art exhibited at the Boston Athenaeum during the antebellum era, see Perkins 1980. Roman Fish Market is listed in Perkins as Arch of Octavius, Jew's Quarter, Rome — emphasizing the site's republican origins and its exoticness. In 1901, a few months before his death, Bierstadt sought to exchange a more recent painting with the Boston Athenaeum for Roman Fish Market. In a letter at the Athenaeum dated 21 November 1901 from C. Loring to C. Bolton, Bierstadt requests the painting back "because he has never of late done work equal to this early specimen. This is a question of 20 years standing. More than once...I have referred him to the Trustees of the Athenaeum." Quoted in the chronology provided by Anderson and Ferber 1990, p. 257. 4. My characterization of the tourist couple in Roman Fish Market as "Yankee" relies on the similarity of the male tourist to other images of Northeastern Protestant American males in the 1840s and 1850s. See Johns 1991, pp. 24-59. Bierstadt clearly makes these tourists Anglo-Saxon and distinguishes them from the physiognomy of the native Romans in the image. Ossoli 1856, pp. 250-252. Margaret Fuller defines three types of Americans abroad: the "servile," the "conceited," and the "thinking." A few observers, including Shelley Mills (in the exhibition brochure for Albert Bierstadt: An observer of air, light, and the feeling of place, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 3 August 1985-6 January 1986), have viewed the ironic nature of the image as "visual wit." Although an "ugly American" discourse existed in the mid-nineteenth century, commentators like Fuller were critical of certain American tourists and their inability to truly appreciate the importance of major sites and museums, not minor, out-of-the-way ruins like the Portico of Octavia. It is my contention that Bierstadt's tourists are not Fuller's "conceited" Americans but her "thinking" tourists, and that the painting's subject was clearly ironic, and perhaps humorous, for its viewers in the late 1850s through the 1870s. 5. There are several examples of the popularity of Murray's handbook among American tourists to Italy, including Kirkland 1849. She writes that "a faithful reading of Murray's Guide Books will give more [information] than one can use," p. vi; and, in commenting on the "interesting objects" that "thicken upon us as we approach Rome" Kirkland mentions that "they are of a kind of which our good friend Murray discourses at full length," p. 278. The Reverend John E. Edwards notes that his touring party "followed the suggestion of Murray's most excellent guide-book" in Edwards 1857, p. 99. Ohioan Samuel S. Cox mentions that "Not only guides in the human shape become essential, but Murray himself began to compensate us for lugging him about," in Cox 1854, p. 109. 6. Bierstadt's first trip to Italy in 1856-7 has been documented but only as a brief early career stop on the way to painting his large canvases of the Rocky and Sierra Nevada Mountains. Modern-era museum publications and exhibitions on American artists, including Bierstadt, in Italy include "Arcady Revisited: Americans in Italy" in Novak 1995, pp. 203-225; Soria 1982; Jaffe 1989; Vance 1989; and Stebbins 1992. For some of the more detailed descriptions of Bierstadt's first European tour, see Hendricks 1973, pp. 21-45; Soria 1982, pp. 66-67; Diana Strazdes, catalogue entry in Stebbins 1992, p. 214; and Tuckerman 1867, p. 388. For artists from Düsseldorf in Rome, see Martina Sitt, "Die Düsseldorfer 'Compagnie' in Rom 1830-1860: Auf Goethes Spuren," in Boerner 1999. For a study of picturesque images of the poor in eighteenth century English painting, see Barrell 1980. The influence of the British landscape categories on American painting is the subject of Ketner and Tammenga 1984. Much has already been written in some of the above scholarly works about the "picturesque" nature of Italy and its historical associations. Numerous authors have demonstrated how the issues for Americans viewing "picturesque" images of Italy, including Roman Fish Market, centered upon the way monarchies and anti-democratic governments degraded their people, contrasted with the relative wealth of opportunities provided individuals in republican America. 7. Although their own Puritan forebears had been forced to leave England in the early seventeenth century, the early settlers of Massachusetts Bay Colony and its later generations maintained a genuine affection for England, including a dislike of Catholicism and centuries of mutual antagonism with the Irish. According to Kerby Miller, the emigrants to the American colonies from Ireland prior to 1776 were only twenty to twenty-five percent Catholics. The statistics in this essay come from Miller 1985 and Handlin 1979. They note that at least ninety percent of the Irish immigrants to Boston in the late antebellum years were Roman Catholics. 8. Examples of scholarship on New England and national culture include Norton 1986 and Buell 1986. 9. Ronald Story, "Class and Culture in Boston: The Athenaeum, 1807-1860," American Quarterly 27.2: 196-198, quoted in Wallach 1998, p. 10. For more on the Athenaeum, see Hoyle 1980, especially Jonathan P. Harding's section "The Picture Gallery." A group of "prominent Bostonians" formally incorporated the Boston Athenaeum in February 1807. The Athenaeum was, according to the A Climate for Art exhibition catalogue, "an organization designed to serve...as a library of literature and science, a museum of natural and artificial curiosities, a repository for models of machines and works of art, and a laboratory for natural philosophical inquiry and geographical improvements." 10. The historiography of American politics in the 1850s is large and substantial. Some of the works that were of great value to this essay include: Schlesinger 1945, Holt 1992, Holt 1999, Foner 1995, and Stampp 1990. An ongoing debate exists among antebellum political historians over how strong the anti-slavery convictions of the Know-Nothing leadership were during the early 1850s, and how nativist the Republican party's mainstream was in the late 1850s. For a recent dialogue on the historiography of the political history of late antebellum America see essays in The Journal of American History 86 (June 1999): 93-166. 11. For more on The Crayon, see Simon 1990 and Grzesiak 1993, especially Alan Wallach's "Introduction: Formulating a High Art Esthetic." The Crayon 5.11 (November 1858): 315-316. The Crayon does note that all hope is not lost for even the poorest Irish immigrants: "[In the United States] a world of romance unfolds itself; for, while the [immigrant] children begin to stammer smart and enterprising Yankee words...some of the gipsy [sic] genius which American progress presents, is undoubtedly due to international amalgamations." Bierstadt's personal views on Catholic immigration to the United States, and his overt intentions for the painting are not made clear by his biographers or by existing written documentation. Bierstadt's family did emigrate from Germany in the early 1830s to the United States. Notwithstanding antebellum nativist sentiment that occasionally singled out German immigrants, a proportion of German immigrants, unlike the large Irish populations in the Northeast, settled in communities in the West. As well, as Matthew Frye Jacobson states, "By longstanding tradition in the high discourse of race, the Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic traditions were closely aligned." He continues: "Anglo-Saxondom represented one branch of a freedom-loving, noble race of Germanic peoples." A noticeable, well-defined "racial" gap, however, existed in the minds of some Americans between Roman Catholic Celts and Protestant Anglo-Saxons. See Jacobson 1998, pp. 45-47. Whatever Bierstadt's specific religious beliefs may have been can perhaps be deduced from the place of his wedding and of his funeral service — Grace Episcopal Church, Waterville, New York, on 21 November 1866, according to Hendricks 1973, p. 165, and St. Thomas's Protestant Episcopal Church in New York City, according to the New York Times, 19 February 1902, respectively. 12. Boston Daily Advertiser, 9 January 1855, and Gardner, "Inaugural Address of 1855," quoted in Mulkern 1990, p. 94. 13. Despite the different set of associations given by Protestant Americans to German Catholic and Italian Catholic immigrants during the antebellum era, the brunt of anti-Catholicism in Massachusetts in the 1850s (due to the sheer numbers of immigrants) fell on the Irish. For Protestant Bostonians, the Irish ethnicity of the immigrants was inseparable from the Catholic religious identity of those same immigrants. See Anbinder 1992, p. 103. The history of politics in antebellum Massachusetts is the subject of Formisano 1983. 14. "Aware that [Rome] was architecturally unworthy of her position as the capital of the Roman Empire...Augustus so improved her appearance that he could justifiably boast: 'I found Rome built of bricks; I leave her clothed in marble.'" Suetonius 1957, p. 69. See also Murray 1858, p. 80. Murray's handbook continues: "This vestibule had 2 fronts, each adorned with 4 fluted columns and 2 pilasters of white marble of the Corinthian order, supporting an entablature and pediment. The portico was destroyed by fire in the reign of Titus, and was restored by Septimius Severus and Caracalla...The 2 pillars and pilasters in the front, and the 2 pillars and 1 pilaster in the inner row, towards the portico, are sufficient to show the magnificence of the original building." Choosing to depict the Portico of Octavia and the "American other," Bierstadt makes reference simply via the setting to the ultimate "other" in Rome itself — the Jews in the Ghetto. Vance points out that Bierstadt includes a "long-bearded rabbi who is the primary indication that the arch demarcated one boundary" of the Jewish Ghetto. Vance also deals with contemporary commentary on the Jewish neighborhood in Vance 1989, II, pp. 153-156. 15. Norton 1855, p. 226. 16. Story 1876, p. 408. Art historian Diana Strazdes has noted that Bierstadt's selection of fish amplifies the "shabbiness of the place." She suggests that he intentionally left out some of the higher quality fish — sea bass, whiting, and sole — for cheaper fish — dogfish, sardines and eels; see Stebbins 1992, p. 214. 17. As just one example of a European artist's depiction of the site, Hubert Robert's painting The Octavian Gate and Fish Market, from 1784 is an oil on canvas, 63 x 45 in, and is in The Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Bequest of Henderson Green. 18. Lester 1853, I, p. 241. 19. Hillard 1853, II, p. 21. 20. Diana Strazdes concludes her remarks on Bierstadt's "picturesque realism" with: "While wishing to convey the decrepitude of contemporary Rome, Bierstadt seems to have been unwilling to detach it entirely from an artful ideal," Stebbins 1992, p. 214. For William L. Vance, Bierstadt's Roman Fish Market is full of irony and paradox. Bierstadt represents "the effort to move toward democratic realism from a starting point in the picturesque, if only by...a sympathetic quick sketch depicting popular activities." I disagree with Vance's characterization of Roman Fish Market as either sympathetic or quick. See Vance 1989, II, p. 145. Vance sets his discussion of the painting into a section entitled "Politics of the Picturesque", II, pp. 139-160. 21. Hare 1874, pp. 164-65, italics in original. Hare's recommendation for a morning light viewing of the portico appears on pp. 5-6. 22. My interpretation of the tropes provided by Bierstadt's tourist couple relies on Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998, especially p. 62. Brigette Bailey, in her essay "The Protected Witness: Cole, Cooper, and the Tourist's View of the Italian Landscape," writes: "Touring the Italian scene offers a pedagogy of identity in which middle- and upper-class tourists learn to use vision both to encounter and to control difference and, therefore, to reconfirm their function as bearers and shapers of the American social vision." In other words, Roman Fish Market's viewers, as vicarious tourists, use their differences with the depicted Catholics to reconfirm their belief in Protestant and republican values. See Bailey's essay in Miller, 1993, pp. 92-111. For theoretical discussions of tourism and modern society, see Urry 1990 and MacCannell 1989. 23. Story 1876, p. 46. Story's chapter from Roba di Roma on "Beggars in Rome" also appeared in Boston's Atlantic Monthly 4.12 (August 1859): 207-219. For more on beggars as "social counterfeits" in the American city, see John Kasson 1990, pp. 70-111. 24. Harper's Weekly, 7 November 1857, p. 720. 25. Whitney 1856, p. 165. The emphasis is in the original. For more on the role of Whitney and the Order of United Americans within late antebellum politics, see Levine 2001. According to Levine, Whitney "was the scion of a long line of small-to-middling commercial proprietors" and "tried his hand at newspaper editing and publishing." See p. 461. 26. I wish to thank the anonymous peer reviewer for reminding me of this comment from the Mercury, 14 December 1858. See Anderson and Ferber 1990, p. 124. 27. Story 1876, pp. 117-119. 28. Harper's Weekly, 6 November 1858, p. 720. 29. Jarves 1856, p. 319. 30. William Sidney Mount's Farmers Nooning, 1836 (The Museums at Stony Brook, New York. Gift of Mr. Frederick Sturges, Jr., 1954) also quotes the Barberini Faun. Elizabeth Johns argues that Mount utilizes an African-American-turned-drunken-satyr in this image to "unequivocally" announce to the painting's viewers that the "main allusion" was to slavery, and that the "unambiguously lazy" African-American affirmed the beliefs of anti-abolitionist New Yorkers like Mount and his patrons. See Johns 1991, pp. 33-38. For another antebellum American quotation of the Barberini Faun, see William Holbrook Beard's A Lesson For The Lazy, 1859 (Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, Vassar College, Gift of Matthew Vassar, 864.1.6). 31. For a version of Euripides's Medea, see Blondell 1999, pp. 169-215. Especially helpful for my understanding of the play was Ruby Blondell's "Introduction," pp. 149-169. The quotation from the chorus is from lines 826-829 of Medea. 32. Joy F. Kasson discusses Story's sculpture in "Domesticating the Demonic: Medea," in Joy F. Kasson 1990, pp. 203-240. On p. 223, Kasson identifies Ristori, and her American tour in the mid 1860s, as the inspiration for Story's sculpture. Leslie Furth also utilizes American interest in Ristori and Medea in Furth 1998. Noticing the number of women with spindles, the Reverend John E. Edwards described their actions: "[S]ome [were] spinning in a style that must be seen to be understood. The flax was attached to a distaff and drawn off to form the thread, which was twisted by twirling the broach on which it was wound with the fingers." See Edwards 1857, pp. 164-165. 33. For more on Ristori and Medea, see Ristori 1907, p. 45: "At the beginning of 1857 I visited, for the first time, the beautiful city of Naples, where on the evening of June 14th, at the Regio Teatro del Fondo, I began with 'Medea,' a short series of my performances"; and Knepler 1968. For nature morte, a still-life motif originating in ancient Rome and particularly popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, especially in the Netherlands and Italy, see Sterling 1952. The Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts owns a stage photograph of Adelaide Ristori in character as Medea showing the described scene. 34. Wallach 1998, p. 38. The politics of defining and representing "others" has more to do with the interests of those with the power to represent other cultures than it does with understanding the groups being represented. Collections have helped establish positions of authority, dominion, and social imperialism over the "collected 'other'" in the service of individual or state sovereignty. See "The American Cast Museum: An Episode in the History of the Institutional Definition of Art," in Wallach 1998, pp. 38-56 35. For more on the Boston Athenaeum's sculpture collection, see Hoyle 1980, especially Rosemary Booth, "A Taste for Sculpture," pp. 23-35. The cast replica of the Barberini Faun is listed in Perkins 1980. Perkins quotes from previous Athenaeum catalogues which cite "Winckelmann" and another author: "'The beautiful Barberini sleeping Faun is no ideal, but an image of simple, unconstrained nature,'" and "'The sleep in which he lies sunk after fatigue, and the relaxation of all the muscles of the limbs, are expressed in a manner which cannot be improved; it is, indeed, inimitable. We can almost hear the deep respiration, see how the wine swells the veins, how the excited pulses beat,'" respectively. Bierstadt has transformed the famous ancient sculptures on display in Rome, and in reproductions in the United States, into physiognomic types. These types and their racial implications were presented in galleries of nations, "types of mankind" exhibitions, crowd scenes, and group portraits of life in European and American cities. For examples of the importance of physiognomic types in nineteenth-century exhibitions see Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998, Sellers 1980, and Altick 1978. 36. Perkins 1980 lists Preparing for Market as by Jerome Thompson (1814-1886). The shared nature of American market spaces serves as the subject of Tangires 1999. |